Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

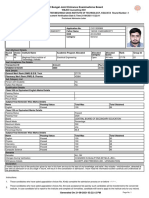

40071168

Hochgeladen von

georgi_stoyanowOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

40071168

Hochgeladen von

georgi_stoyanowCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Interpersonal Relationships, Motivation, Engagement, and Achievement: Yields for Theory, Current Issues, and Educational Practice Author(s):

Andrew J. Martin and Martin Dowson Source: Review of Educational Research, Vol. 79, No. 1 (Mar., 2009), pp. 327-365 Published by: American Educational Research Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/40071168 . Accessed: 06/01/2014 09:34

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

American Educational Research Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Review of Educational Research.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ReviewofEducational Research Spring2009, Vol. 79, No. 1, pp. 327-365 DOI: 10.3102/0034654308325583 2009 AERA. http://rer.aera.net

Motivation, Interpersonal Relationships, and Achievement: YieldsforTheory, Engagement, Current Issues,and EducationalPractice

Australia University ofSydney, Australian CollegeofMinistries

' In thisreview, we scope therole of interpersonal in students relationships and achievement. We that achieveacademicmotivation, engagement, argue current ment motivation issues,and educational theory, practicecan be conterms. attribution Influential theorizing, including ceptualizedin relational theory, theory, expectancy-value goal theory, self-determination theory, selfand self-worth motivation is reviewed in thecontext theory, theory, efficacy others inyoung people's academiclives.Implications oftheroleofsignificant perfor educationalpracticeare examinedin thelightof thesetheoretical A trileve and their constructs and mechanisms. Iframecomponent spectives and relationally work isproposed as an integrative based response toenhance and achievement. This encomstudents' motivation, engagement, framework action (universal and intervention, programs targeted passes student-level extracurricular learnpopulations, activity, cooperative programs forat-risk teacherand classroom-level action(connective instrucand mentoring), ing, teacher retention, teacher training, and tion,professionaldevelopment, and school-level action(school as community and classroomcomposition), leadership). effective studentcognition,student studentbehavior/attitude, Keywords: motivation, teacher education/development. development, of high-quality Few would disputethe importance interpersonal relationships in young people's capacity to functioneffectively, includingin theiracademic notes the substantial role thatrelationships lives. The literature play consistently in students'success at school (e.g., Creasey et al., 1997; Culp, Hubbs-Tait,Culp, & Starost,2000; Field, Diego, & Sanders, 2002; Marjoribanks, 1996; Martin, Marsh, Mclnerney,Green, & Dowson, 2007; Pianta, Nimetz, & Bennett,1997; of relationshipas "a stateof conRobinson, 1995). Guided by a core definition nectedness between people, especially an emotional connection" (Webster's Online Dictionary, 2007), we suggestthattheconceptof relationships providesan forconsideringtheories,issues, and practicesrelevantto organizingframework

Andrew J.Martin MartinDowson

327

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson

achievement motivation. Wealso seektodemonstrate that thegreater theconnectednesson personal andemotional levels(also referred to as relatedness andrelationalprocesses)in theacademiccontext, thegreater thescope foracademic andachievement. motivation, engagement, Thepurposes ofthis article aremultifold. Itelucidates thewaysinwhich relaaffect achievement motivation andthe benefits accrued from tionships considering a relational on achievement of motivation. It describes a number perspective motivationandachievement-related the theories anddemonstrates cenimportant tral roleofinterpersonal ineachofthese theories. Itexplores relationships practical implications ofa relational issuesin ofboth andcurrent understanding theory terms ofpractices tostudent-, andschool-level actions. teacher/classroom-, relating itconcludes with an integrative framework that summarizes conFinally, theory, andpractices relevant to therelational structs, mechanisms, dynamics underpinandachievement intheacademic context. motivation, ning engagement, Figure1 an organizing framework for this review. presents Part I: The Importance and ProcessofRelatedness Positive AreImportant Why Interpersonal Relationships forYoung People A substantial of research demonstrates the of interbody importance positive for human see Berkowitz, 1996; personal relationships healthy functioning (e.g., & Bronfenbrenner, 1986; De Leon, 2000; Fyson,1999; Glover, Burns, Butler, Patten, 1998; Hill, 1996; Moos, 2002; Royal & Rossi, 1996; Sarason,1993; are a majorsourceof happiness and a buffer Weisenfeld, 1996). Relationships stress Glover et & Catano, 1999; al., 1998; against (Argyle, McCarthy, Pretty, individuals receive instrumental tasks and 1990).Through relationships, helpfor emotional in their in shared challenges, support dailylives,and companionship activities & Furnham, & Eccles,2002; Irwin, 1983;Gutman, Sameroff, (Argyle theloss ofrelationship is a source ofunhappiness anddistress 1996).Conversely, (Bronfenbrenner, 1974;Cowen,1988;Gaede, 1985).Interpersonal relationships arealso important forsocialandemotional & Ryan, 2001; (Abbott development & etal., 1990).Forexample, childhood and 1987;McCarthy Kelly Hansen, during andrelyon,positive relationadolescence, involve, keyaspectsofdevelopment are also a critical factor in 1982). Relationships ships(Damon, 1983; Hartup, andmotivation at school(Ainley, & 1995;Battistich young people'sengagement issueis the Horn, 1997;Hargreaves, Earl,& Ryan,1996;Pianta, 1998).Thislatter focus ofourreview. andAchievement Motivation: Relationships Causal Effects and Value-Added Explanations Motivation is defined as a setofinterrelated beliefs andemotions that influence and direct behavior & Marsh,2007; 1999; see also Green,Martin, (Wentzel, inpress). Wepropose that affect achieveMartin, 2007,2008a,2008b, relationships ment motivation motivation's constituent beliefs andemobydirectly influencing tions. socialinteractions teach individuals about themselves andabout what Ongoing is needed tofit inwith a particular individuals beliefs, group. Accordingly, develop and values thatare consistent withtheir relational environment. orientations, 328

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

FIGURE1. Organizing forreview. framework orientathebeliefs, students teaches domain in theacademic Hence,relatedness Inturn, environments. inacademic tofunction andvaluesneeded tions, effectively of enhanced in theform behavior direct and adaptive) thesebeliefs (if positive andself-regulation. goal striving, persistence, 329

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson

beliefs In high-quality individuals notonlylearnthat particular relationships, internalize areuseful for inparticular butthey environments, actually functioning held thebeliefs valuedbysignificant beliefs others (Wentzel, 1999).In thisway, becomea part ownbeliefsystem. In theacademic of theindividual's by others tolead for with a particular teacher arelikely context, example, goodrelationships students to internalize at least some of thatteacher's beliefsand valuesabout schoolandschoolwork. Theseinternalized beliefs andvaluesthen havethepotentialtobe transferred toother learn notonly how academic Thus,students settings. tobehave ina particular student in academic academic but also how to be a setting situations more generally (Ryan& Deci, 2000). Relatedness is an important As such,it has an self-system processin itself. function on theself, ofpositive affect theactivation energizing working through andmood(Furrer from inter& Skinner, 2003).Thisintrapersonal energy, gained a primary toward motivated personal relationships, provides pathway engagement in lifeactivities. A complementary on these is provided processes by perspective theneedtobelong have Thishypothesis that "human hypothesis. suggests beings a pervasive drive to form and maintain at leasta minimum of lasting, quantity andsignificant & Leary, 1995, (Baumeister positive, interpersonal relationships" is fulfilled, thisfulfillment p. 497). Whentheneedforbelongingness produces emotional In theacademic these emotional domain, positive responses. responses are said to drivestudents' achievement to their behaviors, including responses and strategy use (Meyer & Turner, challenge,self-regulation, participation, 2002). Relatedness affects individuals' motivation and behavior by wayof positive influences on other relevant to achievement motivation. Forexamself-processes of a student's emotional attachments to peers, life,positive ple, in thecontext andparents notonlyhealthy andintellectual teachers, social,emotional, promote butalso positive of self-worth and self-esteem (Connell& functioning feelings becauseselfworth and self-esteem areboth Wellborn, 1991).This is important relatedto sustainedachievement motivation 2002; Thompson, (Covington, 1994). relatedness is linked to keypsychological needsin a waythat fosters Finally, achievement motivation. Work on autonomy inprevious decadesis a goodexamandrelatedness havebeenlinked various in (under ple.Autonomy terminologies) work on (a) agency ofan organism as an individual, riseto (i.e.,existence giving andself-protection) andcommunion oftheindi(i.e.,participation self-expansion vidualin a larger riseto cooperation) Bakan (1966); (b) the organism, giving by ofbothindividuational andrelational needsalongthelinesproposed importance orientations toward self-determination and ( 1941, 1965),whoidentified byAngyal self-surrender as complementary and Maslow who needs, by (1968), recognized theneedfor loveandbelongingness inthepath to self-actualization; and(c) individualism and interdependence a framework that (Waterman, 1981) under provides support for the scope of individualistic values to facilitate helping, and other behaviors. of Indeed,theseearlyintegrations cooperation, prosocial andrelatedness havebeeninfluential in later on motivation autonomy theorizing more 2000) andpersonality specifically (e.g.,see Deci & Ryan, generally (e.g.,see MeAdams, & Day, 1996). Hoffman, Mansfield, 330

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Accrued Positive Through Interpersonal Relationships Benefits area number ofbenefits accrued relatedness into There account through taking motivation andprocesses. when achievement theories relatedness First, examining construct which diverse theories ofachievement serves as an explanatory through Infact, even transcend divicanbe integrated. relatedness broader motivation may motivation For the sionsofpsychology belongingpsychology. example, beyond in educational, and social has wide application ness hypothesis personality, a useful & Leary,1995). Second,relatedness (Baumeister provides psychology behavior in the classto view and understand tool with which adaptive diagnostic in the classroom that are other motivation achievement room andtotreat problems in schoolhavebeen and adaptation Forexample, related. problems adjustment needto belong to meetstudents' of learning environments to thefailure linked & McNamara & 1995;Wentzel, 2004).Third, (Baumeister Leary, Barry, Caldwell, ofthe theinterconnectedness accommodates andactively relatedness recognizes educational oftheselfandtheneedfor dimensions andaffective social,academic, & Seligman, interconnectedness this torecognize Kumpfer, (Weissberg, programs and for act as an relatedness can of the 2003). Thus, concept impetus explanation relationthe whole that accommodate educational Fourth, self. positive programs review dealswith relatThepresent intheir ownright. outcomes shipsarevalued withrespect to and practical theoretical ednessas a meansto greater clarity as can also be motivation. achievement However, recognized relationships positive human their valuefor whatever inthemselves. endstates Thus, clarifying important arecritical forunderandrelatedness andachievement, motivation relationships more human widely. functioning standing a closer derived direct benefits more tothese In addition understanding through a closer there in theclassroom, of relatedness yieldsfrom mayalso be indirect ofadapthe effect Relatedness ofrelatedness. consideration why helpexplain may Forexample, there varies acrosscontexts. motivation on achievement tivebeliefs beliefs and of various to the effects with acrossstudies is variation goals respect tobe both Performance motivation. on achievement adapgoalshavebeenshown areinconthese results motivation. for achievement tiveandmaladaptive Clearly, ofperformance debate overtheadaptiveness oftheongoing sistent (for examples & Thrash, see Brophy, Pintrich, Elliott, Barron, 2005; Harackiewicz, orientation, relatedness 2002; Martin, 2006c),anditmaybe that 2002; Kaplan& Middleton, actas a medirelatedness someofthis canexplain may inconsistency. Specifically, In motivation. achievement and interface of to the with variable goals respect ating relationwhere students environments experience positive performance-oriented inthe as being environments these supportive bystudents maybe perceived ships, motivation this is thecase,achievement When toachievement. maybe facilipath On theother orientation. ofa performance inthecontext andsustained hand, tated ofpoorrelationships in thecontext environment a performance-oriented maybe relatedone.Hence, a supportive than rather context as a "dog-eat-dog" perceived debates and current theoretical that can inform nesscouldbe a mediating process inconsistencies. empirical

331

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Part II: Relatedness Motivation and TheoriesofAchievement TheRole ofInterpersonal Relationships and theOther inAchievement Motivation Theory the socialfalls Our analysisof motivation-related theory largelywithin domain andprimarily utilizes (e.g.,Dweck cognitive social-cognitive perspectives intocon& Leggett, 1988;Schunk, 1991).This social-cognitive analysis brings sideration sixtheoretical Eachofthese while maintaining viewpoints, viewpoints. in theway in differs therelevance of relationships to their conceptualizations, are attribution whichinterpersonal are invoked. These viewpoints relationships self-effiself-determination theory, theory, expectancy-value theory, goaltheory, that notall theories andselfworth motivation Itis important cacytheory, theory. socialare historically we invoke their theories social-cognitive perse. Rather, that other elements for thepurposes ofoursynthesis. Wealso recognize cognitive as a sourceof theories elements (notaddressed here)includesocial-cognitive influence. Rationale fortheChoiceofTheories Theories in thisstudy frameworks in achievement motivation represent major havebeendeveloped overthepast40 years that research drive current (Mclnerney & VanEtten, ofwriting we conducted a somewhat 2004).Atthetime expeditious oftheEducation to search Resources Information Center (ERIC) databaselimited that are:(a) journal with motivaarticles, reviewed, (b) peer (c) dealing publications tion and/or achievement as keywords from thesixtheoretical outlined, (d) positions written in English, of and(e) published since2000 (inclusive). searches Through and/or ontosubject this identified closeto 1,500artikeyword mapping headings, cles dealingwith"self-efficacy" "achievement "self-worth/self-esteem", goals", and "self-determination". "attribution/s", "goal orientation", "expectancy/ies", Whilst we recognize that thisis an everchanging and fluidtallythat does not denote these constructs1 relative orsubstance, we present thetallies to importance demonstrate thecurrent andrecent relevance ofthese constructs andthetheories towhich inpublished relate educational research. they Thesetheories also share a common Social-cognitive social-cognitive heritage. theories inter andbehavior examine, alia,cognition (e.g.,attributions, expectancies, and vulnerabilities) that are contextually needs,capacities, purposes, perceived located andinfluenced. Thisis not toimply that the is explicit placeofrelationships andcentral ineachtheory; when itcomestooperationalizing thetheories however, inachievement motivation there is often a clear relevance for research, interpersonal this relevance is thefocus ofthepresent review. Indeed, relationships. we propose that areimportant to achievement motivaAlthough relationships thisdoes notmeanthat theroleof self-generated andemotions tion, cognitions - as do thetheories - that should be ignored. We recognize theself we examine haspowerful of its own. that inaddiwe generative capacities Similarly, recognize tionto relatedness and itsimpact on motivation, and achievement, engagement, there is thekeyissueof students' academic Thisproficiency encomproficiency. skillssuchas critical andmetacognition, passesgeneral thinking, self-regulation, 332

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and Student Motivation andEngagement Relationships as well as more-specific and mathskills,such as decoding texts, comprehension, ematicalreasoning.Hence, we suggestthatrelatednessis a necessarybutnotsufin educationaloutcomes. ficient conditionforexplainingvariation Reviewof Theories thecauses individualsattribute Attribution theory. Accordingto attribution theory, and behaviorally to eventshave an impacton theway theycognitively, affectively, respond on futureoccasions (Schell, Bruning,& Colvin, 1995; Weiner, 1986, in the literature: to attributions are typicallyidentified 1994). Four attributions For example, failureon an exam may be and effort. luck, task difficulty, ability, or insufficient effort. to bad luck,difficult attributed questions,low ability, can also be mapped accordingto their These causal attributions locus, stability, and controllability (Weiner, 1994). Thus, the causes of an eventmay be located withinthe personor externalto theperson,may be stable or unstable,or may be in interest The controldimensionis of particular controllableor uncontrollable. of students' determinant thisreviewbecause it tendsto be a significant responses to setback,pressure,and fearof failure(Borkowski,Carr,Rellinger,& Pressley, & Hales, 1990; Martin, Marsh,& Debus, 2001b). Borkowski, 1990; Groteluschen, thefeedbackthey One means by whichstudents gain a sense of controlis through otherssuch as theirparentsand teachers (Fabricius & receive fromsignificant Hagen, 1984; Weiner,1986). The significanceof this otherperson an important is established,at least in mechanismfora sense of control,and this significance It has been suggestedthat of therelationship. thenatureand strength part,through control(or helplessness)is learnedby observingpowerful models,such as parents & Furthermore, Maier, 1993). parentsand teacherswho pro(Peterson, Seligman, and feedback thatare commensuratewith students'perforvide reinforcement mance enhance students'perceivedcontrolover educational outcomes (Perry& attributional Tunna, 1988; Thompson,1994). Hence, a defining aspectof students' learn control students can Put determined. in is simply, partrelationally profiles othersrelateto them. othersand theway these significant thesesignificant from context in theinterpersonal It has also been suggestedthatattributions give rise to socially based emotions(Hareli & Weiner,2002). Recent work has proposed inferences thatsocially based emotionsare theresultof attributional focusingon outcome (Hareli & Weiner,2002). This can the perceivedcauses of a particular In an adaptive theobserver'semotionsdirectly. have two impacts.First,it affects can to effort success student's another student a scenario, experience attributing positive affectand feelingsof admirationforthatstudent.On the otherhand, a to a lack of abilitymay anotherstudent'spoor performance studentattributing experience negative affect(Hareli & Weiner,2000). In both cases, emotion is make about othstudents the attributions evoked in the academic contextthrough ers' academic outcomes.There is a second way sociallybased emotionsemergeas about thecause of inferences. a resultof attributional Here, observers'inferences an eventcan shape the student'semotionsand behavior.For example, observers about and make inferences (e.g., teachers,parents)view a student'sperformance thecauses of the outcome,and these theninfluencethe student'sreactionsto the outcome and subsequent behavior. In the adaptive scenario described above, a can evoke positiveaffect a student'ssuccess to effort teacherexplicitly attributing

333

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson and feelingsof pridein thestudent. attributOn theotherhand,a teacherexplicitly and shame in to a lack of abilitymay evoke negativeaffect ing poor performance thatstudent. the attribuAgain, academically relatedemotionis evoked through tionsforsuccess and failurein a relationalcontext, and thisemotionhas achievement motivationrelevance. Taken together, on the matterof relatedness and thesefindings underscore"the interconnection of the self and others attributions, in achievement and thenecessity of a transactional settings, analysisto understand thesocial dynamicsthataccompanyachievement (Hareli & Weiner, performance" 2002, p. 191). Atkinson(1957) viewed the motivation to achieve sucExpectancy-value theory. cess as a product of theindividual'sperceivedprobability of success and theincentivevalue of thatsuccess. Similarly, the motivation to avoid failurewas seen as a of of failure and the product perceived probability negative incentivevalue of failure.More recentformulations of expectancyvalue theory (e.g., Eccles, 1983; Wigfield,1994; Wigfield& Tonks, 2002) have refinedand extendedAtkinson's that(a) theexpectancy-value framework can be originalformulation by suggesting to the whole of not the behavior, behaviors; (b) applied range just risk-taking of an individual's motivationis based on the valuing of proximal and strength distaloutcomesassociated witha behavioror pattern of behaviors;and (c) motivationis dependenton the perception of the likelihoodof a desiredoutcome occuron a behavioror pattern of behaviors(see also Nicholls,Cheung, ring,contingent Lauer, & Patashnick,1989; Wigfield& Tonks,2002). In an educationalcontext, students who believe theyare capable of mastering their schoolworktypically have positiveexpectations forsuccess and, hence,high motivation and achievement(Nicholls et al., 1989). What further contributes to students' motivation and achievement is their valuingof an academic task,as well as the interface of theirexpectancies and task values (Arbreton& Blumenfield, 1997; Eccles, 1983). In a recentmodel representing the developmentof students'expectanciesfor success and task values, Wigfieldand Tonks (2002) identified therole of significant socializes' attitudes, beliefs,and behaviorsin the developmentof students' expectanciesand values. In particular, expectanciesand values are influenced by the socializes withwhom students have significant Thus, expectanrelationships. as an important cy-value theoryimplicatesrelationships componentof its theoreticalframework, and expectanciesand values may be conceptualizedas being, in part,relationally determined. Goal theory. Goal theory focuses on the meaningstudents attachto achievement situationsand the purpose for theiractions (Ames, 1992; Barker,Dowson, & 2002; Dweck, 1992; Pintrich, Marx, & Boyle, 1993). Goals proposed Mclnerney, in early theorizing were the desire to affirm competence(masterygoal) and the desire to demonstrate superiority (performance goal). More-recent developments in goal theoryhave added social goals. Social goals focus on social reasons for such as affiliating withothers,gaining approval fromothers(e.g., achievement, and and parents peers), complying with group norms (Dowson & Mclnerney, 2001, 2003; Elliot, 1997, 1999; Mclnerney,Roche, Mclnerney,& Marsh, 1997; Middleton& Midgley,1997; Urdan & Maehr, 1995).

334

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation andEngagement Relationships

hasnowalsointroduced anapproach andavoidance Goal theorizing distinction et Barker Goals be as being 2002; Elliot, al., 1997). (e.g., may conceptualized ortoward avoidance. directed toward that draw approach Approach goalsarethose in an activity. Avoidance withdrawal from activities or goals drive participation and ofnegative and avoidance implications consequences. Mastery, performance, axes. A mastery avoidance social goals can be locatedon approach-avoidance thedesire nottofailatdeveloping a performastery, example, represents goal,for nottodemonstrate lackofability, anda social mance avoidance goal as thedesire toavoiddisapproval from avoidance working mainly parents example, goalas,for and teachers 2003; Elliot, 1997; (Barkeret al., 2002; Dowson & Mclnerney, 2001,2002b,2006a). Martin, their oravoidance, thegoalsstudents directed toward Whether adopt, approach and achievement are related to effects on motivation and their relative importance, of others theinfluence Dowson,& Van Etten, 1998; Hinkley, (e.g., Mclnerney, link a significant Martin etal. (2007) demonstrated Wentzel, 1994).Forexample, andstudents' orientaofteacher-student the between mastery relationships quality & Maehr,1994; Meece, 1991,for tionandavoidance goals (see also Anderman a and students' ofteacher behavior other goals).Theyalso demonstrated aspects withpeersand their between association (a) students' relationships significant orcaregivwith andavoidance relationship parents goalsand(b) students' mastery of relational et al., 1997 fortheinfluence ersandthesegoals (see also Creasey ofteachthere with contexts Indeed, impacts maybe different peersandparents). Martin et al. (2007) found andpeers on different ers,parents, goals.Forexample, andavoidon students' hadthemostimpact with teachers mastery relationships havethe that ancegoals,andDowsonandMclnerney (2003) found may parents most impact on students'social goals. All this suggeststhat the goals ofthe arenotindependent andthewaythese students goalsareexpressed, adopt, For and havewith students oftherelationships influence teachers, peers, parents. from and as both can be students' this reason, being arising conceptualized goals & in relational contexts fulfilled Salmon, Giwin, (see also Lemos,1996; Stipek, 1998;Taylor, 1995). MacGyvers, self-determination reviewed theories Ofthe here, theory theory. Self-determination as a fundamental of relatedness in its themost is among ingrerecognition explicit at and to function forone to be motivated that It proposes of motivation. dient needsmust be supported a setofpsychological 2000; (Deci & Ryan, level, optimal & Ryan, La Guardia 2002; Reeve,Deci, & Ryan, 2004). Theseneedsarerelatedandsense to theconnection Relatedness refers andautonomy. ness,competence, therequired andbelonging Thisconnectedness with others. ofbelonging provides deal andeffectively needto actively that individuals emotional explore security worlds. with their stubetter a strong senseofrelatedness a learning From positions perspective, that setpositive totakeon challenge, dents high expectations goals,andestablish a motivating needsconstitute relatedness them. and motivate extend Moreover, circumto interpersonal and adapting social regulations forinternalizing force is needs relatedness these In & Guardia stances turn, 2002). meeting (La Ryan, of theclassand socialworld theaffective to negotiate to enablestudents likely with interfaces affective andsocialintegration andthis enhanced room andschool, 335

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson

enhanced motivational etal.,2003; & Skinner, 2003;Weissberg (Furrer processes etal.,2004).Forexample, Wentzel tothe extent that home andschool expectations with their andgoalsarealigned, children whoaremore involved parents warmly in class,andchildren with a heightened better academic experience functioning senseofrelatedness with aremore at schoolanddisplay parents higher engaged self-esteem whileat school(Avery & Lynch, & Ryan,1987;Ryan, Stiller, 1994). relatedness with also predicts relatedness with teachers Quality parents quality (Ryanetal.,1994). is centrally relevant toindividuals' belief Self-efficacy theory. Self-efficacy theory in their to successfully outgiven tasksandtheconsequent capacity carry impact thisself-belief has on motivation andachievement 1986,1997;Schell (Bandura, et al., 1995; Schunk a & Miller, is hypothesized to support 2002). Self-efficacy such that in and test individuals generative capacity high self-efficacy generate alternative courses ofaction whenthey do notmeet with initial success(Schunk, 1991 & Miller, canalsoenhance one'sfunction; Schunk 2002).Highself-efficacy elevated one's levelsof effort andpersistence andcan also enhance ingthrough to deal with situations and emotional ability problematic byinfluencing cognitive related tothesituation & 1986,1997;Zimmerman, Bandura, (Bandura, processes Martinez-Ponz, 1992). Students can gaina senseofself-efficacy theproblem-solving modelthrough communication ofsignificant others 1997).Moreover, (Bandura, ingandsupportive thosewith whomstudents andto whomthey arecloselyconnected are identify channels ofthismodeling andpositive communication (Bandura, more-powerful & Miller, is a mecharelatedness 1997;Meece,1997;Schunk sense, 2002).In this nism which takes a influFurthermore, through modeling place. keyinterpersonal enceon self-efficacy is thevicarious influence from others socialmodels through efficacious andthe extent towhich reasons, (Bandura, self-beliefs, 1997).Forthese these areheldbyself, can be conceptualized as a relationally influenced process. And although is often discussedin individualistic boththe terms, self-efficacy extent to which beliefs overtime andthewaysthese beliefs self-efficacy change affect motivation and achievement are determined in the social domain(e.g., & Martin, inpress). Bandura, 1986;Parker Hence,self-efficacy maybe conceptualized in relational terms rather thanin solelyindividual terms 1991; (Schunk, Schunk & Miller, a focusfor future relationresearch is whether 2002). Perhaps area moderator ofthese suchthat relatedness low)and ships processes (e.g.,high, interact to affect achievement motivation or whether relatmodeling (e.g.,yes,no) ednessis a mediator ofthese suchthat achievement processes modeling predicts motivation factors. bywayofrelational motivation Self-worth motivation describes thebasesof, Self-worth theory. theory andthe involved or one's selfworth in, processes protectingenhancing (Covington, tothis students' selfworth is largely derived 1992,1998,2002).According theory, their toperform andcompetitively 2002; through ability academically (Covington, cometo equatetheir worth with is Robinson, 1995).One reasonstudents ability that their inpart communicated tothem made conis worth, others, bysignificant ditional on achievement. Theseconditional havea significant then, relationships, on students' to self-protect 1992; Martin, 2002c, impact propensity (Covington, 336

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation and Engagement Relationships

suchself-protection can havea negative & Marsh, 2007; Martin 2003). In turn, students' and achievement on 1992; Martin, (Covington, engagement impact that stu& Debus,2001a,2001b,2003; Thompson, Marsh, 1994).Thissuggests affects theconditionality of thoserelationships, dents'relationships, especially andachievement. thetheir motivation andthen their self-worth Thus,self-worth inrelational terms. orymayalso be conceptualized andDebus(2003) an empirical From Martin, Marsh, Williamson, perspective, self-worth andthespecific motive to protect that students' haveshown strategies In particular, others. areinfluenced in which bysignificant they engagetodo this in their fearof failure. werea factor students' found that Theyalso parents they wasresponded to(e.g.,through that fear characteristic that the found wayinwhich linked to thecharacteristic was often or defensive pessimism) self-handicapping and This ofthefamily with their own fear. dealt their in which impact parents way theintergenerational research is supported relatedness demonstrating by other on students' withdrawal ofapproval andtheimpact offailure offear transmission offailure fear 2004). (Elliot& Thrash, From Ideas Emanating Theory Summary ofKeyRelational conandachievement-related aboveidentifies The discussion keymotivationdirected or and connectedness, ideas, processes byrelatedness, underpinned cepts, inTable 1. Attribution is presented oftheselinkages A summary andbelonging. inone'slifeandthe andevents tooutcomes on thecausesascribed focuses theory Personal and cognition. on behavior, of thesecausal attributions affect, impact orpatthe attributional or modeled be learned attributions on, from, "styles" may of a sense as attributions of ofothers. terns (such personal consequences Specific ofsignifiandobservation from feedback can also be developed control) through toachieve andagency inone'scapacity toa belief refers cantothers. Self-efficacy and agencycan be instilled This senseof capacity outcome. a desired through from others. and or vicarious direct influence, modeling, opencommunication linked tosocialhavealsobeensubstantively andvalues tothis, Related expectancies ofbehavior, focuses on thewhy Goal theory andbehaviors. izers'beliefs, attitudes, of and the values can be communicated which expectations significant through andorganizational atindividual, others levels). Self-determination group, (working the which is satisfied for need onthe focuses relatedness, through psychological theory motivation -worth others. of significant and nurturance Self warmth, support, that It demonstrates worth andachievement. on thelinkbetween focuses theory in which life in child's the determined worth, thislinkis in part relationships by orunconditional ineither conditional arecommunicated andapproval affirmation, ways. Part III: A Trilevel ApproachtoActionFroma RelationalPerspective then motivation to achievement is central relatedness that To theextent theory, terms. inrelational can also be framed tomotivation relevant educational practice on rests educational andconsider toorganize heuristic A useful practice bywhich intervention andatwhich unfold outcomes educational tiers atwhich themultiple arenot andpractice tointervention Tiered canbe directed. andpractice approaches diverse in as best advocated been have and uncommon practice addressing recently Institutes andchallenges andhealth-based education(e.g.,see National problems 337

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

TABLE 1

theories andkey relevant torelatedness Summary ofkey concepts

Theory Attribution theory Key concepts Perceived causes of an event or outcome shape behavior, and cognition;key affect, - control, causal ascriptions locus, stability Positiveexpectationsand high value placed on task or outcome enhances motivation Link to relatedness or theother Perceivedcauses learnedor inferred fromsignificant others;dimensionssuch as controlshaped by feedback fromothers Socializers' beliefs,attitudes, and behaviors communicatelevel of expectationand nature of value Communicatedthrough others'values, and group expectations, norms Relatedness need metthrough and warmth, support, nurturance Modeled and communicated others; by significant vicarious influence fromothers Relationships(approval, conditional affirmation) on level of achievement; specificresponseto fear of failurelinkedto how othersrespond significant

value Expectancytheory

Goal theory

Reasons forengagingin a behavioror particular a pursuing particular goal

Self-determination Relatedness a psychological need theory Self-efficacy Belief in capacityto achieve in a specificdomain or task

Self-worth motivation theory

Link betweenworthand achievement;fearof failure

ofHealth, Institute ofChildHealth andHuman 2008,andNational Development, are now 2008, forlinksto research alongtheselines).Such tiered approaches identified as particularly in reaching effective diverse with populations varying andtypes ofneed.The tiered is also a useful degrees approach wayoforganizing thediscussion of relational action. we consider relatedness at the Accordingly, three levels that characterize the natural structure ofstudents' educational typically atthelevelofthestudent, atthelevelof environs, (a) practice (b) practice namely, theteacher orclassroom, and(c) practice attheleveloftheschool. We argue that action in this trilevel fashion an integrative analyzing represents means to address relational inthecontext oftheory. To support bywhich practice this we to the fact that research has on focused one ormore argument, point previous ofthese three levels toenhance the ofpedagogy (Hill& Rowe,1996;Kontos quality & Wilcox-Herzog, middleschooling 1997b;Marzano, 2003), improve (Eccles, 338

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and Student Motivation andEngagement Relationships

of boys(Martin, theeducational outcomes 2003a,2003b,2004; 1999),enhance students assist Australian 2003), (Munns,1998), Indigenous Weaver-Hightower, students theeducational needsofdisadvantaged & Horn, address 1997; (Battistich transition educational Becker& Luthar, 1998;Maehr& (Barratt, 2002), smooth andbuoyancy 1996;Martin, 2008a),andbuildresilience (Cunningham, Midgley, & Johnson, & Marsh, & Frydenberg, 2000; Martin 1999;Howard 2006, Brandon, 2008,inpress). in PartII are also useful in from outlined derived The keyprinciples theory each of the three levels of intervention. to consider at elements key identifying ateachlevelthat involves orencompasses topractice be looking Thus,we should in PartII. in thekeytheories discussed detailed andmechanisms keyconstructs for the identified substantive Pintrich lines, (2003) recently questions Alongthese underscore these science. Taken motivational of a together, questions development a modelofmotiandarticulating ofconsidering, theimportance conceptualizing, attrirelated toself-efficacy, salient andseminal from vational theorizing practice and and valuing,goal orientation, self-determination, butions,expectancy self-worth perspectives. to recognize that no one it is important As we discusseach levelof practice, torelational interfor an encompassing condition is a sufficient approach practice effective aremost ofa tiered inthecontext vention. model, Moreover, approaches mentora schoolimplementing Forexample, ifintegrated. learning, cooperative effort as its to extracurricular or an only targeted activity approach expanded ing, theinterpersonal is unlikely toachieve needsofitsstudents therelational tomeet from to be derived thebenefits this. than of schoolsdoingmore Likewise, yields the fullness of such that sufficient if is not limited there will be any depth practice that a powerful Wepropose, addressed. is notamply onepractice then, implemenonbreadth, belowwillrest described ofthevarious tation depth, quality, practices andintegration. Level at theStudent Practice andintervention, student universal we emphasize Atthestudent level, programs extracurricular at-risk student activity, populations, assisting programs targeted atthe other aremany there andmentoring. practices Although learning, cooperative becausethey these we emphasize facilitate levelthat student relatedness, practices to described oftheory areunderpinned above, opportunities represent byelements studentin and are between connectedness enhance individual, students, grounded outcomes. educational toenhancing orstudent-to-adult to-student, approaches andIntervention Student Universal Programs inthere are many described foundations In terms of thetheoretical earlier, enhance not that students in which andout-of-school school only engage programs butalso offer outcomes and prevent academicoutcomes scope for maladaptive issueofAmerican a recent anddevelopment Psychologist, (indeed, growth personal foryoung and interventions on suchprograms 38 (6-7), 2003,focused people). to students' to build offer basedrelational Evenbroadly bridges scope programs butareoften academiclives.Such programs purpose rangein specific typically behavinstudents' orintervening aimedatenhancing emotional, social,physical, These and academic ioral, interpersonal comprise positive programs development. 339

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson relaand support, feelvalued,developingsupportive relationships helpingstudents tionships,establishing a meaningfulplace for the individual in a group, and individuals'usefulnessto others(Dryfoos,1990; Martin,2008a; Nation fostering et al., 2003; Weissberget al., 2003). Martin(2005, 2008a) also identified elementsthatcontribute to effective motivationand engagement interventions based on theseminaltheory describedabove. The first elementcomprisedoptimistic heldby adultsforthestudents, expectations directlyinvokingself-efficacy principles throughthe modeling of efficacious behavior by adults and expectancy-value principles throughcommunicating to students & Tonks, efficacy-related expectations (e.g., see Bandura,1997; Wigfield was a second element,invoking 2002). A focus on mastery principlesof goal thethe importanceof significant adults in shaping students'goals ory thatidentify see Anderman & et Maehr, 1994; (e.g., Creasey al., 1997; Meece, 1991). These adults are also influential in shapingthe climate,the thirdelementidentified by Martin. Specifically,a climate of cooperation,consistentwith goal theoryand relevant climateresearch(Ames, 1992; Dweck, 1992; Elliot, 1997; Qin, Johnson, & Johnson, 1995; Roeser,Midgley,& Urdan,1996; Urdan,Midgley,& Anderman, with relatednessneeds, consistent 1998), evokes a sense of belongingthatfulfills self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 2000; La Guardia & Ryan, 2002). This theory climate of cooperationalso serves to diminishevaluativeconcernsand a consemotivationtheory quent fear of failure,in keeping with tenets of self-worth (Covington,1992, 1998, 2002; Martin& Marsh,2003). Student Targeted Programs forAt-Risk Populations: Special Focus on IndigenousStudents As discussed, universal intervention programs typically involve practices directed at all students, whether be highor low achievers, or unmomotivated, they tivated.However,therehas been some concernthatsuch programsmay increase thegap betweenthestrong and thestruggling students such that thestrugglers gain butthestrong a relational gain more(e.g., Ceci & Papierno,2005). We proposethat on educationalpracticemay hold specificand differentiated benefits perspective forgroupsthatare at risk,even undera universalintervention paradigm.To illuswe focus on students from trate, disadvantagedgroups.Althoughthesegroupsare of student means of by no means exhaustive groupsat risk,theyare an informative examiningthe potentialfora relationalapproach in addressingtheireducational needs. In manycountries, a distinct Indigenousstudents represent groupof disadvanIn Australia, forexample,across reading, mathematical and tagedstudent. literacy, scientific achieve at a muchlowerstandard thantheir literacy, Indigenousstudents and the dropoutrate in high school is markedly non-Indigenouscounterparts, forIndigenousgroups(Groome & Hamilton,1995; Martin, 2003c; Munns, higher has foundthattheimpact 1998). Research conductedamong Indigenousstudents of positiverelationships on a numberof educationaloutcomescan be substantial (see, e.g., Collins, 1993; Groome & Hamilton,1995; Richer,Godfrey, Partington, & Harrison,1998). Given thefactthatmanyIndigenousstudents Harslett, experience difficulties withtheirteacher,interpersonal are a criticalconrelationships cern when schools are seeking to enhance Indigenous students' educational outcomes(Richeret al., 1998).

340

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation and Engagement Relationships relevant to theeducationalneeds Reviews pointto threelevels of relationships of Indigenousstudents (Martin,2006a, 2006b; Munns, 1998; see also Fanshawe, involvesan activedaily connectionwiththeschool. This relation1989). The first ship is underpinnedby ongoing connections with the Indigenous community, and a focus on the interests IndigenousStudies as partof the generalcurriculum, theseaspects of relationship as a policy priority. of Indigenousstudents Together, with school enhance students'academic and nonacademic morale (Fanshawe, relation1989; Martin,2006a, 2006b; Munns, 1998). The second, interpersonal trust within theclass to know teachers' involves students, developing getting ships, and school, and developing Indigenous culturalknowledge and understanding. withstudents involvesconnecting The third, by means pedagogical relationships, and positive instructional of challengingand interesting work,effective strategies, In thecontext of Indigenouseducation, held by teachersforstudents. expectations and respectinclude teacher this of satisfaction, appropriate relationship predictors and effeccollaborativelesson planning, fulviews of students' Indigenousstatus, tiveearlyintervention (Munns, 1998). Taken together, policies and programming and pedagogical relatednesscan be an organizingconcept school, interpersonal, - and potentially the educationaloutcomes of Indigenousstudents forimproving and groups. educationaloutcomesof otherdisadvantagedminorities In line withthis,lessons learnedthrough Indigenous education are echoed in Graham(1994), forexample,developed a those learnedin otherculturalsettings. Americans.Notwithstanding motivation forconsidering amongAfrican taxonomy themfromotherracial historicaland social factorsthatdistinguish the important framework that this Martin provideda usefulmeans by (2003c) suggested groups, which to think about Indigenous students' educational status and outcomes. psychologymust Accordingto Graham,a centralelementof such a motivational of achievement addresssocializationantecedents Similarly, pedagogical strivings. principleshave been drawn fromthe work of Ladson-Billings with exemplary teachers of AfricanAmerican students(Ladson-Billings, 1995). According to through responsiveteacherscreate social interactions Ladson-Billings,culturally connectedness relationships,demonstrating maintainingfluid teacher-student and encouragingstudents of learners, withall students, developinga community these are principlesof effecAs can be readilysurmised, to learncollaboratively. withany group.However,theyhave particutiveteachingthatshouldbe effective withstudents and in particular lar scope forclassroomscharacterized by diversity, who are academically disadvantaged, such as Indigenous minorities (e.g., NativeAmericans)and educationallydisadvantagedethIndigenousAustralians, nic minoritiesand groups (e.g., AfricanAmericans and Mexican Americans), wheretheyare mostneeded. Extracurricular Activity traversein-school and out-of-schoolprograms. involvements Extracurricular activitiessuch as involvement Extracurricular encompasses, among otherthings, evidence of The church. and suggeststhatmost music,dance, clubs, weight sport, in youngpeople's lives,including are a positiveinfluence activities extracurricular in theireducational,social, and emotionallives (Barber,Eccles, & Stone, 2001; Cooper, Valentine,Nye, & Lindsay, 1999; Eccles & Barber, 1999; Marsh, 1992; & DuBois, 2002). Marsh & Kleitman, 2002; Valentine,Cooper, Bettencourt,

341

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson

relatedness are andbelonging areimportant reasons suchactivities Significantly, to yieldpositive effects. Extracurricular thought people activity provides young with safeandcaring environments & Langman, 1994)inwhich (McLaughlin, Irby, & Stattin, Schweder, 2001; Roth& Brooks-Gunn, prosocialadults(Mahoney, and model effective consistent behaviors, 2000) areable to promote self-efficacy with & Miller, 1997;Schunk (Bandura, 2002).Extracurricular self-efficacy theory socialskills andsocialcapital build(Broh, 2002),thereby activity helpsdevelop senseofcontrol, as articulated 1986, (Weiner, inga student's byattribution theory & Tunna, consistent 1994;see also Perry 1988;Thompson, 1994),andautonomy, with a self-determination & Ryan, 2000; La Guardia (Deci & Ryan, perspective extracurricular an adoles2002; Reeveet al., 2004). Moreover, activity provides centwitha senseof belonging to a personally valuedgroup(Brown& Evans, from andself-determination frame2002),harnessing principles expectancy-value works & Tonks, that these (Deci & Ryan,2000; Wigfield 2002). To theextent connections andmodeling arealigned with academic havethe goals,they potential topromote achievement motivation. a relational framework underHence, through in salient extracurricular can facilitate pinned by principles theorizing, activity educational andother outcomes. Cooperative Learning Alsorelevant atthestudent levelandrelated inpart togoaltheory is the relative oncooperative andcompetitive oratleasta relational) (relational) (antiemphasis activities can be operationally defined as thepresamongstudents. Cooperation ence ofjointgoals,mutual shared andcomplementary roles rewards, resources, & Johnson, students strive toreach situations, (Qin,Johnson, 1995).Incooperative their thesupport andjointfocus ofothers intheir orclass.In goalsthrough group students strive toreach their oragainst situations, competitive goalsindividually, than others & Maehr, et al., 2002). Thus, (rather 1994;Barker with) (Anderman whereas is focused onthenotion ofrelatedness andmutual action with cooperation theother, thenotion ofcompetition tends tobe antithetical to it.Evidence suggests that efforts aremore effective than efforts for cooperative competitive many learningrelated such as those andrecallofinformation tasks, (Barker involving decoding etal.,2002;Johnson, & Skon,1981),andmore conJohnson, Nelson, Maruyama, duciveto higher levelthinking and problem et al., 1981; Qin (Johnson solving etal., 1995;Slavin,1983).Cooperative theorists suchfindlearning might explain that thepursuit ofjointgoalsandmutual rewards andthesharing ingsbyarguing ofintellectual andphysical resources on relatedness andinter(all factors relying contribute to theadvancement of achievement and motivation connectedness) these outcomes. underpinning Mentoring Within the school environment, harnesses relatedness between mentoring students andolder students whoprovide andguidance (oradults) younger support in particular domains. is implemented in numerous Mentoring ways,including schoolstudents, school highschoolstudents "adopting" elementary elementary schoolstudents students skills for better activity days(e.g.,high teaching younger former students theschool(e.g.,toencourage orto schoolwork), visiting reading on academic underachievers identify postschool pathways relying engagement), 342

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation andEngagement Relationships to work with,or pairings in partnership with local choosing a teacher-mentor It Noble & has been that the enhanced Bradford, 2000). (see suggested industry connectednessthatis partof these programscontributes to directly interpersonal and achievement gains (Karcher,Davis, & Powell, 2002). In a recent engagement thedevelopment of students' model representing expectanciesforsuccess and task socializers' values, Wigfieldand Tonks (2002) emphasized the role of significant (e.g., mentors)beliefs and behaviors on the academic developmentof students. at least in part, students From a self-efficacy gain a sense of efficacy, perspective, and communication of others the modeling supportive through problem-solving (Bandura, 1997). Mentors are likely to be powerfulchannels of modeling and and so quality relatednessin the mentorprocess is an positive communication, partof this. important Practice at theTeacherand Classroom Level traditions in PartII is therole thetheoretical themeunderpinning A pervading motivation. of teachers(and classroom factors)in shapingstudents'achievement and locus a of control sense that students Attribution through gain theory proposes a sense of control feedbackfromteachersor by observingmodels demonstrating & Tunna, 1988; Petersonet al., 1993; Thompson, (Fabricius& Hagen, 1984; Perry the role of significant 1994; Weiner,1986). Expectancy-valuetheoryidentifies of students' socializers' attitudes, beliefs,and behaviorsin thedevelopment expectancies and values (Wigfield & Tonks, 2002). From a goal theoryperspective, influence thegoals students teacher-set tasks,assessment,and grouping strategies adopt (Anderman& Maehr, 1994; Meece, 1991). Belongingnessin theclassroom, is cultivated centralto self-determination by the teacherand the students theory, collected in theclassroom (Deci & Ryan,2000; La Guardia & Ryan,2002; Reeve themodelingand supet al., 2004). Studentsgain a sense of self-efficacy through worth motivation a selfFrom teachers of communication (Bandura, 1997). portive see also et al. 1992, Williamson, Martin, Marsh, (2003; Covington, perspective, is self-worth motiveto protect 1998; Thompson, 1994) have shownthatstudents' influenced by teachers while other research has demonstratedthe impact of on students'fearof failure(Elliot & Thrash,2004). Indeed, approvalwithdrawal witha sense students teacherand classroompracticecan be a vehicleforproviding of being at one withthe group along the lines of communionposited by Bakan butnonoverretain thecomplementary some fourdecades ago and yetlet students of student is a hallmark that of sense motivation, engagepersonalagency lapping ment,and achievement(Bakan, 1966; see also, for early work,Angyal, 1941, 1965; Maslow, 1968; Waterman,1981; forlater work,see Deci & Ryan, 2000; McAdams et al., 1996). All thisbeing the case, it is clear thatthe means by which teachersand classand indirectly are directly motivation achievement roompracticeaffect shaped by relationalfactorsand processes. At the teacherand classroom level, we suggest and and training, teacherretention thatinstructional, professionaldevelopment, factors relational of these in terms can be conceptualized practices organizational the emerging and processes. In particular, may concept of connectiveinstruction theimportance forteachers'ongoingprofessional have implications development, and attracting of teacherretention prosocial and positive(young) adultsto teacher and the motivation classroom nature of the and compositionin affecting training,

343

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson of students and classroomclimate.Althoughnottheonlyteacherand engagement classroompracticesthataffect achievement motivation, theyare a usefuland informativemeans by whichto framepracticein relationalterms. ConnectiveInstruction To the extent thatrelationships are a vital underpinning of student motivation, and achievement, teacherswho frame terms are engagement, practicein relational more likely to fostermotivated, engaged, and achieving students.Many studies supportthis contention(e.g., Abbott & Ryan, 2001; Battistich& Horn, 1997; Elicker & Fortner-Wood, 1995; Fyson, 1999; Kontos & Wilcox-Herzog, 1997a, researchsupports thefollowingpoints: 1997b; Martin,2006d). Specifically, a. Students'sense of support(e.g., being liked, respected,and valued by the teacher)predictstheirexpectanciesforsuccess and valuingof subjectmatter.Indeed, support fromteacheris a consistently influential in motifactor vationand achievement (Goodenow, 1993a). b. Students who believe that their teacheris caringalso believe theylearnmore (Teven & McCroskey,1997). c. Students'feelingsof acceptance by teachersare associated withemotional, cognitive, and behavioral engagement in class (Connell & Wellborn, 1991). d. Teacherswho support a student's tendto facilitate motivaautonomy greater and desireforchallenge(Flink,Boggiano, & Barrett, tion,curiosity, 1990). e. Teachers higherin warmth tend to develop greaterconfidencein students (Ryan & Grolnick,1986). researchalso supports thefollowingconclusions: Conversely, f. Whenteachers are morecontrolling, students tendto showless mastery motivationand lowerconfidence (Deci, Schwartz,Sheinman,& Ryan, 1981). evince lower motivation g. Teachers who are notperceivedas warmtypically and achievement (Kontos & Wilcox-Herzog,1997b). among students are centralto the issue of teachingand instruction. The therefore, Relationships, builton thepreviously instruction, conceptof connective proposedpastoral peda1994; Martin, 2006a, 2006b), relational gogy (Cavanagh, 2001; Hunter, pedagogy (Bergum,2003; Boyd, MacNeil, & Sullivan,2006; Gadow, 1999), and connective pedagogy (Corbett,2001a, 2001b; Corbett& Norwich, 1999), is relevanthere. Pastoralpedagogy,introduced by Hunter(1994), describedhow modernteachers harnessprinciplesof the Christianpastorateto shape the ethical development of students to pedagogythat has (see also Cavanagh,2001). Relationalpedagogyrefers as its foundation the need forgood relationships betweenstudent and teacherthat must also be accompanied by enhanced studentlearning (Boyd et al., 2006). of ExtendingGadow's (1999) work,connectivepedagogy deals withthe delivery connects with learners,seeks to make the learning teachingthatinterpersonally material form of connection), connectswithexternal sec(i.e., another meaningful torsto maximizestudent and looks to connectwithsignificant others, development,

344

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation andEngagement Relationships such as parents,in students'lives (Corbett,2001a, 2001b; Corbett& Norwich, 1999). Martin & Pallotta-Chiarolli, 2003; Munns,1998, (2006a, 2006b; see also Martino offered an adaptationof these notionsto more centrally forcognateperspectives) in thecontext and connectedness betweenteacherand student positionrelatedness - as - connective itself. Martinproposedsuch instruction instruction of instruction and teacheron threelevels: thelevel of substance thatwhichconnectsthe student level (see also the interpersonal and subject matter, level, and the instructional connective instruction Martino& Pallotta-Chiarolli, Munns, Hence, 2003; 1998). substantive connection between the three (the relationship relationships: comprises - i.e., connecting and substanceof whatis taught and thesubjectmatter thestudent and betweenthestudent to thewhat),theinterpersonal (theconnection relationship - i.e., connecting to the who), and the instructional the teacherhimselfor herself and theinstruction or teaching betweenthestudent (theconnection relationship connective instruction to thehow).Although i.e., connecting emphasizestheimpact on teachersuch thatthe thereis also an impactof student(s) of teacheron student, teacheris able to refineor adjust subject matter, relatedness,and interpersonal on thebasis of students' instruction responsesto the teacher'sconnectiveinstruction.Connectiveinstruction, then,may be viewed as a bidirectional process thatis to bothteacherand student. beneficialand enhancing mutually in conto thewhat).The first connectiveness Substantive relationship (connecting and is thatbetween the studentand the actual subject matter nectiveinstruction natureof tasks conductedin the teachingand learningcontext.Core elementsof conto theteachingand learning connection students' thatfacilitate subjectmatter work that is tasksthatare appropriately textincludesetting challenging, assigning intocontent and assessmenttasks,and and meaningful, buildingvariety important to young people (e.g., utilizingmaterialthatarouses curiosityand is interesting Covington, 1998; Martin,2002a, 2003a, 2003b; Mclnerney,2000). These eleand learningtasks to which a studentcan mentsreflectcontent,subject matter, connect.These are a means by which the student engages withthe meaningfully A good deal of thiscomponentof relationalpedawhatof teachingand learning. and the mastery theory gogy restson the valuingdimensionof expectancy-value which emphasize relevance,contextualdimensionsof dimensionof goal theory, in learning and satisfaction interest, (see Eccles, 1983; Elliot, utility, subjectmatter, 2000; Wigfield,1994; Wigfield& Tonks,2002). 1997, 1999; Mclnerney, in connectiveness (connectingto thewho). The second relationship Interpersonal and theteacher. is thatbetweenthe student framework theconnectiveinstruction in the of quality interpersonal characteristics relationships Previouslyidentified to students' views, allowteachingand learningcontextinclude activelylistening to knowstudents, to have inputintodecisions thataffect them, getting ing students students' all but no favoritism students, individuality, accepting affirming showing forstudents and havingpositivebutattainable (Martin,2002a, 2003a, expectations 2003b; Slade, 2001; see also Flink et al., 1990; Goodenow, 1993a; Teven & theyields of such relationalcharacterMcCroskey,1997, forresearchconfirming engages withthewho in istics). These elementsare a means by whichthe student invokesinterpersonal This component context. theteachingand learning explicitly

345

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson - and by implication is perhaps as centralto learningand instruction relationships mostclosely aligned withself-determination and its relatednessconstruct theory related(Ryan & Deci, 2000). Whereas othertheoriesmight relyon interpersonal ness moreas a conduitfortheir constructs and processes (e.g., forenhancingselfcontrol,self-worth, efficacy, theory expectations,valuing)- self-determination relatednessas an important quite centrally comprises the need forinterpersonal end in itself. Instructionalconnectiveness(connectingto the how). The thirdrelationshipin connectiveinstruction is thatbetweenthe student and the teachingor instruction itself.Elementsof effective instruction forstuinclude maximizingopportunities dents to develop competence,providingclear feedback to students, explaining intoteachingmethods, thingsclearlyand carefully, injectingvariety encouraging studentsto learn from their mistakes, clearly demonstrating to studentshow schoolworkis relevant or meaningful, all students ensuring keep up withthework, and allowing for opportunities to catch up (e.g., Baird, 1999; Bandura, 1997; Covington,1997; Craven,Marsh,& Debus, 1991; Martin,2002a, 2003a, 2003b). These elementscharacterize instructional high-quality practiceand are a meansby whichthe student engages withthehow of teachingand learning. They bringinto considerationteacher-based behaviors that emphasize effectivefeedback and reward(attribution of students' theory), nurturing expectanciesand valuingof submatter of a mastery and improvement ject (expectancy-value theory), development focus (goal theory),use of modeling (self-efficacy theory),and reductionof achievement stressand fearof failure(self-worth motivation theory). The role of the studentin connective instruction. Connective instruction also at each of the three Rather, recognizesthatteachingis nota unidirectional process. levels (substantive, and instructional) there is theopportunity forthe interpersonal, teacherto refine or adjust therelevant level. For example,in responseto a lack of student interest in a particular how lesson, theteachermight adjust subjectmatter, he or she is relating to students, theinstructional theminterpersonally techniques selves, or a combinationof these. Hence, in the truespiritof relatedness,there existsa bidirectional beneficialto all parties. process potentially mutually In sum,connective instruction relatedness is an instrucexplicitly recognizesthat tionalneed and thatstudents are likelyto be moreengagedand motivated whenthis needis met(Battistich & Horn,1997; Burroughs & Eby,1998; Chavis& Newbrough, 1986; N. Fry, 1994; Fyson, 1999; McCarthyet al., 1990). Throughmeetingthis relatedness instruction facilitates students' identification withthe need, connective school and providesa connection withinstruction on a moremeaningful basis (see identification withschool and connection withinstruction are Munns,1998). Jointly, and motivation. proposedto promote adaptiveacademic engagement ProfessionalDevelopment Seminal motivation and conceptualizingaroundinstruction itself(e.g., theory connectiveinstruction) can also be a basis forteachereducationand professional 2001a; development (Bergum,2003; Boyd et al., 2006; Cavanagh, 2001; Corbett, and preserviceeducation Hunter,1994; Martin,2006a, 2006b). Teacher training have been a focus of much priorresearch,witha numberofjournals specifically

346

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and Student Motivation and Engagement Relationships devotedto it. However,relatively less attention has been givento theprofessional of teachers in the workforce. development has thepotential Teacherprofessional forenhanc(or in-servicing) development and assistingteachersto operate more ing the educational outcomes of students in the classroom (Rowe & Rowe, 1999). Cherubini,Zambelli, and effectively Boscolo (2002) examined the effectsof professionaldevelopmenton teachers' studentmotivation. Teachers participatedin professional success in facilitating developmentrelated to theoreticaland methodological aspects of motivation Their findings to modifyand sustainstudentmotivation. researchand strategies their about student motivaincreased showedthat knowledge practical participants and considermotivational able to identify tion,werebetter problems,and planned to sustaintheirstudents'motivation new instructional (see also Schorr, programs in profesfound that teachers et al. (1998) 2000). Similarly, participating Stipek motivation were morelikelyto emphasize sional development focusingon student and to encourage student in their and understanding autonomy, teaching, mastery teachers to create psychologically safer classroom environments. Participating - an important motivation assessmentsof students' also made more-accurate preintervention and targeted cursorto effective (Martin,2008a). Recent reviewshave pointedto the need forteacherprofessional development that one of the It is noteworthy in assistingdisengagedand disadvantagedstudents. teacher-student is for such areas development improving professional targeted key and researchdetailedin 2002). Integrating (Becker & Luthar, theory relationships Parts II and III suggeststhatprofessionaldevelopmentalong these lines should focuson (a) developinga sense of community relationally through among students & structures school Horn, 1997; Cumming, 1996); (Battistich supportive climates as articulatedin goal (b) cultivating cooperative and mastery-oriented within their students peer groups(Bolger, (Qin et al., 1995); (c) integrating theory with & Kupersmidt, Patterson, 1998) to develop a sense of belongingconsistent control in the and self-determination (d) personal theory; developingcompetence relatedness(Connell & Wellborn,1991) along the lines contextof interpersonal and attribution of that articulatedunder self-efficacy principles,respectively; with (Flink et al., 1990), consistent (e) reducingemphases on teacher-as-authority also above introduced connective instructional 2003; (see Bergum, principles 2001a, 2001b; Hunter,1994; Martin, Boyd et al., 2006; Cavanagh, 2001; Corbett, 2006a, 2006b); and (f) providing positiverole modeling(Hernandez, 1995), conThese are all a means of intentionally sistentwithself-efficacy directing theory. of teachingand learntoward relationalunderstandings development professional and of motivationing. This accords withour overallrelationalconceptualization achievement-related keyissues, and practicesdescribedabove. theory, and Training TeacherRetention In almost every organizationalsetting,the workplace is changing,and at a seeminglyincreasingpace (Schabaracq & Cooper, 2000). Most employees work remunerated (Dollard, 2006). Reports of an long hours, oftennot sufficiently in and less involvement into decision less of lack control, making, input increasing associated with theschedulingof worktasksand methodsof workare consistently workers' poorer well-being (Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Indeed, stress-related in Australia rate. For at an to rise continue claims example, alarming compensation

347

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Martin & Dowson

for thepresent stress-related claimsincreased than (thecontext authors), bymore 60% between1996-1997and 2002-2003(Office and of theAustralian Safety ofworking more than half Council, States, 2006),andintheUnited Compensation adults areconcerned abouttheamount of stress in their lives(Stambor, saythey relevance tothis someresearchers review, 2006).Ofparticular placeschoolteachers amongthegroupof employees facingmanyor all of theabove pressures in press).Suchresearch & Marsh, has identified (Martin stress, disengagement, little andhigh turnover inthis workloads, heavy support, setting (Fry challenging & Martin, 1994;Mayer, 2006; McCormack, Gore,& Thomas, 2006; Richardson & Watt, & Robinson, thatsignificantly 2006; Smithers 2003)- factors hamper individual career andemployment It is important to notethat such development. factors also leadtohigh rates ofteacher andevendifficulattrition, high mobility, tiesattracting sufficient numbers ofteachers into teacher & Martin, (G. Fry training for Economic andDevelopment, 1994;Organisation 2005; Smithers Co-operation & Robinson, 2003;Vinson, 2002). Oneofthe effects ofteacher attrition andmobility is that there arefewer opportunities for consistent andstable between student and teacher and, relationships by fewer consistent lives. implication, prosocialand positiveadultsin students' failure to attract to teaching meansa more Similarly, potentially good teachers limited suchpeoplefor children andyoung pool ofavailable peopleandtheconcostofthis interms ofchildren's andyoung sequent people'spotentially supportive interpersonal The present echoes calls in other review, then, relationships. research for needed andschools to more deal with support byteachers effectively thestressors that lead to attrition, andalternative career choices(G. Fry mobility, & Martin, inpress; & Marsh, etal, 2006; 1994;Martin 2006;McCormack Mayer, for Economic andDevelopment, & 2005; Richardson Organisation Co-operation & Robinson, Watt, 2006; Smithers 2003;Vinson, 2002). Classroom Composition Froma relational it is also important to consider thenature and perspective, number ofstudents inthe classroom. as key theories If, (e.g.,goaltheory, self-efficacy attribution motivation and achievement are affected theory, theory) propose, by andmodelswith whom one identifies other goal climates, students), peers, (e.g., then itfollows that research andpractice must lookmore closelyat thecomposition ofstudents intheclassroom. To date, most multilevel research variance inachievement andmotiexamining vation at theclassroom levelattributes suchvariance to theteachers themselves & Theodorakis, Marsh, 2004;Rowe& (e.g.,see Hill& Rowe,1996;Papaioannou, little has attempted todisentangle the Rowe,1999).Relatively research, however, effects oftheteacher from those oftheclass.If,for there is an effect of example, classcomposition onmotivation andengagement, then there areimplications from a relational Someimmediate from an achievement motivaperspective. questions tionperspective wouldbe: Whatstudents arecollected How many are together? there? Where arethey seated? Whom do they work with oralongside? Howdo they interact? Howdo they geton? therelative roleofteacher from that ofclasscomposition is most Disentangling handled cross-classification inwhich there are appropriately bymultilevel analyses each of whom teaches classes. and teachers, Marsh, Martin, Cheng multiple multiple 348

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

andStudent Motivation and Engagement Relationships (2008) conducted such analyses and showed that therewere some differences did notalways generalizeover different betweenclasses butthatthesedifferences classes taught are the by the same teacher.Hence, over and above teachereffects The researchers concludedthat boththequalityof the effects of class composition. in motivation (see also Martin teachingand theclassroomcompositionare factors & Marsh,2005). which sughas implications forclassroom climateresearch, This achievement of theparticular collecclimatemay also be a function geststhatthemotivational in thatclass. Whereas in recentyears therehas been substantial tion of students of effective and characteristics focus on teachereffectiveness teachers,it might now be timelyto revisitthe issue of class compositionand perhapsfroma relain the contextof achievementmotivation, tional perspective.More specifically, of effective the characteristics researchmight classrooms,thestudents investigate in theclassroom,thebases on whichtheyare collectedtogether, collectedtogether themselvesare otherfactors and how theyinteract. Moving beyond the students relatednessamong stuthataffect relevantto the classroom and its environment and teachers.These include such factorsas theclassdentsand betweenstudents andequipment, offurniture room'sphysicalspace (encompassingsize, organization etc.), its locationin theschool itself(e.g., in termsof noise, temperature, lighting, to otherclassrooms forease of movement, etc.), and even the timeof proximity Prior workhas been conducted are conducted. activities classroom which at day into cognate issues such as seating arrangement (Hastings & Schwieso, 1995; & Hartig, 1999), streaming(Marsh, 1987; Marsh & Hau, 2003), Marx, Fuhrer, single-sexclass composition(Marsh, 1989; Marsh & Rowe, 1996; Martin,2004; of thelearningenvironment Martin& Marsh,2005), and thephysicality (O'Hare, factors 1998; Stone,2001). Hence, class compositionand otherclass environment are an avenue forfurther motivation and achievement a relational from perspective such researchwould also need research.Moreover,froma relationalperspective, at the class level is a to establishhow much variance in achievementmotivation interactions of teacher-student function (i.e., class-level variancedue to teacherinteractions student (i.e., relatedness)and how muchis unique to student-student class-level variancedue to student-student relatedness). Practice at theSchool Level indiwithintrapsychic, thisdiscussion deal primarily The theoriesinforming small groupsand at individualsor relatively thatare directed vidualisticconstructs and the like. activatedby individualssuch as teachers,counselors,psychologists, may be morealigned withresearchand practice Althoughtheissue of relatedness to considerwhatapplicaat the individualand interpersonal level, it is important of treatment can be directedat the school level. A thoroughgoing tion of theory at all levels: student, recommendations relatednesswould encompass integrated are undergoal theory teacheror classroom,and school. For example,hypothesized masteryand performanceclassroom climates that also have implications for whole-school climates (e.g., see Duda, 2001; Middleton & Midgley, 1997; Papaioannou et al., 2004; Roeser et al., 1996; Urdan et al., 1998). The notionof withpreat the school level is notinconsistent fearof failureand disengagement theories(Atkinson, motivation dictions under need achievementand self-worth 1992, 1998; McClelleand, 1965). Workin theareas of attributions 1957; Covington,

349

This content downloaded from 62.44.96.2 on Mon, 6 Jan 2014 09:34:45 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions