Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Workload, Work Stress, and Sickness Absence in Swedish Male and Female White Collar Employees.

Hochgeladen von

maxmunirOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Workload, Work Stress, and Sickness Absence in Swedish Male and Female White Collar Employees.

Hochgeladen von

maxmunirCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 2006; 34: 238246

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Workload, work stress, and sickness absence in Swedish male and female white-collar employees

GUNILLA KRANTZ1 & ULF LUNDBERG2

1 2

Centre for Health Equity Studies (CHESS), Stockholm University and Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, and Department of Psychology and Centre for Health Equity Studies (CHESS), Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

Abstract Aims: This study aimed to analyse, in a homogeneous population of highly educated men and women, gender differences in self-reported sickness absence as related to paid and unpaid work and combinations of these (double exposure), as well as to perceived work stress and workhome conflict, i.e. conflict between demands from the home and work environment. Methods: A total of 743 women and 596 men, full-time working white-collar employees randomly selected from the general Swedish population aged 3258, were assessed by a Swedish total workload instrument. The influence of conditions in paid and unpaid work and combinations of these on self-reported sickness absence was investigated by multivariate regression analyses. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess differences between men and women. Results: Overtime was associated with lower sickness absence, not only for men but also for women, and a double-exposure situation did not increase the risk of sick leave. Contrary to what is normally seen, conflict between demands did not emerge as a risk factor for sickness absence for women, but for men. Conclusions: Our assumption that sickness absence patterns would be more similar for white-collar men and women than for the general population was not confirmed. However, the women working most hours were also the least sick-listed and assumed less responsibility for household chores. These women were mainly in top-level positions and therefore we conclude that men and women in these high-level positions seem to share household burdens more evenly, but they can also afford to employ someone to assist in the household.

Key Words: Conflict between demands, gender differences, sickness absence, total workload, white-collar employees, workhome conflict, work stress

Introduction A range of factors have been shown to be associated with sickness absence in empirical studies, such as conditions that are specific to a certain workplace (personnel policy, size and type of workplace) and the individuals work environment (physical and chemical agents, qualification requirements, role clarity, fairness in division of work tasks, wage system, monotony of work) [13]. In the Whitehall II study, as in other studies, work characteristics, such as low levels of job control, lack of variety and use of skills, high work pace, and low support at work and low levels of job satisfaction, were identified as risk factors for sickness absence

[1,4,5]. However, stressful episodes in private life, such as economic difficulties, poor social network and support, divorce, serious illness of a family member, or having children at home, were also shown to predict absences but to a higher extent among women than among men [1,6,7]. A number of studies further indicate an inverse relationship between employment grade and sickness absence and a gender difference, with women being more frequently sick-listed than men [811]. In Sweden, sickness absence rates have increased continuously since the 1980s, but more prominently during the 1990s and to date, for both women and men with womens number of days of absence per year exceeding that of men. Currently, sickness

Correspondence: Gunilla Krantz, Centre for Health Equity Studies, CHESS, Stockholm University and Karolinska Institutet, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden. Tel: +46 (0)8 674 73 60. Fax: +46 (0)8 16 26 00. E-mail: gunilla.krantz@chess.su.se (Accepted 23 August 2005) ISSN 1403-4948 print/ISSN 1651-1905 online/06/030238-9 # 2006 Taylor & Francis DOI: 10.1080/14034940500327372

Workload, work stress, and sickness absence absence rates have decreased marginally, with an average number of registered days of sickness absence of 18 for women and 11 for men [12]. Women account for 62% of all sickness absence days. The overall trend is that costs related to sickness absence have decreased somewhat while at the same time costs for early retirement pensions have increased and the resulting net effect is a marginal increase in total state expenditure [12]. Womens higher sickness absence rates have been discussed in terms of the high total workload and the double-exposure situation: being in paid employment and at the same time shouldering the main responsibility for household chores and child care [13,14]. Further, a relationship between occupational gender segregation and sickness absence rates has been shown for women, with higher incidence and duration of sickness absence for women in maledominated occupations as compared with the situation in gender-integrated occupations [15].

239

Aims Obviously, conditions at work and in private life are different for men and women and for people from different social strata. This study therefore aimed to analyse gender differences in associations between self-reported sickness absence days and total workload, operationalized as paid and unpaid work conditions and combinations of these, as well as perceived work stress and conflict between demands in a homogeneous population of highly educated, full-time employed men and women. One assumption guiding this research was that a traditional gender pattern in division of paid and unpaid work would be less prominent in this group of highly educated participants.

home, and 275 men and 275 women, without children at home being approached and asked to participate, in all 2,600 persons. This is a cross-sectional study with all the data based on self-reports. A questionnaire containing items relating to socioeconomic factors, total workload (TWL), perceived work stress, and sickness absence during the last year was mailed to the selected participants and filled in anonymously. A reminder was sent after three weeks. In all, 1,690 answered the questionnaire (65% response rate), but 352 were excluded due to not fulfilling the criteria set for participation, as they were currently either on sick leave, parental leave, in part-time employment, or failed to respond to items related to their total workload. As a result, the statistical analyses were based on data from 743 women and 596 men. The following occupational levels were represented: (1) top managerial level, director, managing director, deputy executive; (2) upper middle managerial level, head of a large division with 1150 employees; (3) lower middle managerial level, head of a small division with up to 10 employees; (4) semi-managerial level, e.g. foreman without formal personnel responsibilities; (5) no managerial duties. The Total Workload instrument Total workload encompasses paid and unpaid forms of productive activity, as described by Kahn [16]. A persons total workload thus encompasses paid employment, overtime at work and unpaid work duties, such as household chores, child care, care of elderly or sick relatives, work in voluntary organizations, unions and so on. To measure aspects of total workload in female and male white-collar employees, a Swedish total workload (TWL) instrument, developed and psychometrically evaluated by Ma rdberg and colleagues, was used in this study [17]. It contains scales for measuring perceived total workload and control in the household. Calculation of total workload and work stress Each individuals TWL was calculated by adding up self-reported data relating to the average number of hours a week devoted to (a) paid employment and overtime at work, (b) household duties, such as food shopping, washing dishes, house cleaning, preparing food, laundry, gardening, house repairs, and (c) child care (homework/teaching, care-taking, playing, pick up/drive children to school, and other activities).

Material and methods Selection of subjects In 2001, samples of men and women were selected randomly by Statistics Sweden, according to the following criteria: belonging to the white-collar sector, at least 35 hours of regular employment a week, and participant age 32 to 58 years. Four occupational areas were represented: (a) technology and natural science, (b) education, (c) health care and (d) administrative work. Women and men were matched for age, occupational level, and children below the age of 18 living at home. This resulted in 1,025 men and 1,025 women with at least one child under 18 years of age living at

240

G. Krantz & U. Lundberg To estimate the effect of combined exposure (i.e. paid and unpaid work interaction and workchild care interplay), a multivariate analysis was performed with a combined variable. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) was used for all statistical purposes [18]. Statistical significance was determined at the 95% confidence interval level. This project was approved by the Ethics Committee at Stockholm University.

The items making up the four indices related to perceived work stress, i.e. the subjective TWL indices, were calculated using mean raw scores (scale 17) and were as follows [17]: (1) Perceived TWL: too much to do on and off the job, overall stress, demands (1.1) Stress from paid work: too much to do at work, stress, demands at work (1.2) Conflict between demands or work-home conflict; child care and household chores contribute to TWL (2) Control over household work: influence at home, control, opportunity to make own decisions The indices Stress from paid work and Conflict between demands are subscales of Perceived TWL [15]. Consequently, these indices were correlated with Perceived TWL, 0.75 and 0.76 respectively. The correlation between Perceived TWL and Control over household work was low, 0.20. The TWL variables and the work stress indices were further dichotomized at the higher quartile of the distribution. Calculation of sickness absence The item used was: Have you been on sick leave in the last 12 months? and If so, for how many days? Total number of absence days was reported but not number of episodes, which makes it impossible to distinguish between short and long spells of absence. The variable was dichotomized into no days of sick leave as opposed to any days of sick leave. Statistical analyses Gender difference in total workload and sickness absence was tested by analyses of variance (ANOVA), fixed model. Odds ratios were used to estimate the bivariate associations between total workload variables and perceived work stress indices in relation to any days of sickness absence. The bivariate analyses were further supplemented by multiple logistic regression analyses to adjust for age, cohabitation status, number of children living at home, and occupational level, as the matching of participants was not completely successful for occupational level. However, as hardly any difference in the risk of sickness absence was detected when compared with the bivariate analyses, these data are not presented.

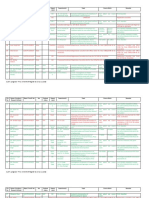

Results Sociodemographic data revealed that somewhat more men than women were in top-level positions, while more women than men (19% women and 11% men) were living without a partner. Of those living without a partner, 75 (53%) women and 11 (17%) men had at least one child younger than 18 years of age living at home (Table I). Women had a higher total workload than men and spent more time on household work and child care but fewer hours in paid work than men did, as displayed in Table II. Furthermore, women obtained higher scores (scale 17) on all the workstress indices than men and a statistically significant difference was obtained through analysis of variance, with pv0.0001 [19]. Although almost as many men as women reported days of sickness absence, the mean number of days of absence was twice as high for women as for men, 12.6 and 6.6 respectively (Table III). In relation to age groups, the same trend in sickness absence was seen for men as for women; in the youngest age group (3234), 9% of the women and men respectively had been on sick leave in the last 12 months, while in the other age groups the level varied between 21% and 26% for both the female and male populations. Furthermore, a short period of absence (13 days) was the most commonly occurring pattern in all age groups for both women and men. However, having been absent from work forw60 days in the last year proved to be twice as prevalent among females as among males, 5.4% and 2.7% respectively. Analysing patterns of sickness absence in relation to employment grade revealed that the top-level managers reported the lowest number of days of absence. In all positions, more women than men reported sickness absence days, apart from the toplevel managers, where only 22.9% of the women reported days of absence as compared with 29.1% of the men (Table IV). Moreover, the mean number of days of absence for women exceeded that of men in

Workload, work stress, and sickness absence

Table I. Sociodemographic data for study participants. Women N No. of participants Age of participants 3234 3539 4044 4549 5058 Total No. of children under 18 years of age 0 1 2 37 Total Occupational level 1. Non-managerial 2. Semi-managerial 3. Lower middle 4. Upper middle 5. Top Total Family type Living without partner Living with partner Total Family type with children under 18 years Living without partner Living with partner Total Educational level Secondary education; 12 years University/college Total 743 65 131 151 175 220 742 191 237 248 67 743 367 174 79 87 35 742 140 603 743 75 477 552 41 697 743 9 18 20 24 29 56 92 113 125 208 596 149 168 206 72 595 267 140 69 65 55 596 64 531 596 11 435 446 77 516 595 % N Men % 596 9 16 19 21 35

241

26 32 33 9

25 28 35 12

47 25 11 12 5

44 24 12 11 9

19 81

11 89

14 86

3 97

6 94

13 87

Table II. Gender differences in TWL hours and for the subjective TWL indices (mean values). Significance tests were performed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) (df51/1336, child care df51/996). Gender differences Women hours/week Hours/week TWL Paid work Household work Child carea Other unpaid work Subjective TWL indices (scale 17) Perceived TWL Stress from paid work Conflict Control over household

a

Men hours/week

85.0 43.8 15.8 19.1 6.3 4.8 5.1 3.9 5.2

77.6 46.3 10.3 13.9 7.1 4.4 4.8 3.3 4.9

17.14 37.45 157.92 21.44

v0.0001 v0.0001 v0.0001 v0.0001 n.s. v0.0001 v0.0001 v0.0001 v0.0001

84.10 35.42 90.42 42.15

Including only those with children (18 years of age at home.

242

G. Krantz & U. Lundberg

Table III. Gender difference in sickness absence: Number of days in the last year, mean values (n5596 men and 743 women). Sickness absence n Men Women

a

% 35.9 39.2

Mean 6.61 12.61

SD 27.69 45.51 0.0 0.0

Percentiles 3.0 5.0

Fa 25/50; 75 7.99

p 0.005

214 291

Analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Table IV. Difference in sickness absence between men and women in various work positions, lowest to highest (15): Number of days; mean values (n5596 men and 743 women). Sickness absence n 1. Non-managerial Men Women 2. Semi-managerial Men Women 3. Lower middle Men Women 4. Upper middle Men Women 5. Top Men Women

a

Mean

SD

Fa

102 145 55 76 24 30 17 32 16 8

38.9 39.8 39.6 43.9 34.8 38.0 26.2 37.2 29.1 22.9

7.2 12.4 9.0 14.9 6.9 6.6 2.5 17.2 2.1 5.6

27.33 44.47 37.64 53.82 26.37 24.97 11.39 52.11 5.60 25.44

2.90

0.089

1.19

0.276

0.01

0.938

4.97

0.027

0.99

0.320

Analysis of variance (ANOVA).

all positions apart from the lower middle managers. Women in upper middle managerial positions reported the highest number of days of absence (mean 17.2) and a statistically significant gender difference was obtained for this group. When analysing the variables reflecting the actual time spent on the various activities, the most striking finding was that spending more than 50 hours/week in paid work guarded against sickness absence, with an odds ratio (OR) of 0.67 and a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 0.451.00 for women and OR 0.49 (0.340.72) for men (Table V). Some 18% of the women and 33% of the men were in this situation, equivalent to overtime work of more than 10 hours a week. Of the work-stress indices, stress from paid work emerged as a statistically significant risk factor for women, with OR 1.63 (1.192.22), while conflict between demands, i.e. perceived workhome conflict, was a statistically significant risk factor for men, with OR 2.19 (1.313.68). Whether a double-exposure situation would give rise to effect modification of sickness absence was

analysed by constructing a combined variable of paid work and a high level of household responsibility (Table VI). No such effect was seen, for either men or women. The same results were obtained when analysing paid work combined with a high level of child care, i.e. no synergistic effect was detected (not in table). The strong favourable effect of spending more than 50 hours/week in paid work, which was obvious for both men and women, led us to investigate sociodemographic and work-related factors in more detail for these particular groups of men and women. Compared with the total female population (see Table I), the majority of these women were in the age group 5058 years (45%), somewhat more women were living without a partner (21%), the majority had no children at home (35%) and a considerably higher percentage were in a top-level position at work, i.e. 12% as compared with 5% for the total female population. Furthermore, fewer women in this group shouldered the main responsibility for household tasks and child care and fewer women experienced conflict between demands

Workload, work stress, and sickness absence

243

Table V. Association between work-related factors and self-reported sickness absence for women and men, presented as crude odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) (n51,339; 743 women and 596 men). Women Sickness absence Variable: TWL variables: Total workload: v82 h/week w82 h/week Paid work: v50 h/week w50 h/week Household work: v20 h/week w20 h/week Child care: v21 h/week w21 h/week n % % OR 95% CI n % Men Sickness absence % OR 95% CI

528 208

71 28

39 42

1 1.16

0.831.60

459 131

77 22

34 44

1 1.49

1.002.22

594 137

80 18

41 32

1 0.67

0.451.00

395 194

66 32

41 26

1 0.49

0.340.72

446 265

60 36

37 43

1 1.30

0.951.77

500 64

84 11

35 46

1 1.61

0.952.74

290 119

39 16

39 45

1 1.29

0.841.99

278 74

47 12

36 47

1 1.61

0.962.71

Work stress indices: Perceived TWL: Low/moderate 242 High 11315 Stress from paid work: Low/moderate 466 High 253 Conflict between demands: Low/moderate 310 High 143 Control of household work: Low/moderate 471 High 252

33 46

35 1.58

1 1.002.48

279 63

47 11

36 43

1 1.31

0.752.29

63 34

35 47

1 1.63

1.192.22

450 131

76 22

34 43

1 1.43

0.962.13

42 19

40 42

1 1.06

318 0.711.59

53 72

34 12

1 53

2.19

1.313.68

63 34

40 38

1 0.91

0.661.24

464 109

78 18

37 34

1 0.88

0.571.37

(10%) as compared with the total female population. However, more women felt stress from paid work (53%) as compared with what was found for all females in this study. When investigating the men with long working hours, we found that also more men were in top

positions, more men felt stress from paid work (36%), but only 9% experienced conflict between demands as compared with the 19% in the total male population. Apart from this, there were no striking differences compared with the total male population.

Table VI. Effect modification of the combined exposure to paid work and household work with regard to sickness absence for women and men, presented as age-adjusted odds ratios with confidence intervals (95% CI). n5743 women and 596 men. Women n Paid Paid Paid Paid work work work work v50h/w w50h/w v50h/w w50h/w and and and and household household household household workv20h/w workv20h/w workw20h/w workw20h/w 350 90 220 40 OR 1 0.55 1.13 1.18 95% CI n OR 326 0.50 1.69 0.48 Men 95% CI 1 0.330.76 0.913.12 0.151.54

0.320.92 0.801.59 0.612.30

169 47 16

244

G. Krantz & U. Lundberg encounter more frustration at and after work, were also believed to contribute to the difference in myocardial morbidity [23]. The favourable effect found of working long hours in relation to sickness absence has several possible explanations. There is reason to believe that employees at higher managerial levels are highly motivated and refrain from staying at home when ill, sometimes referred to as sickness presence; also their job duties are not as physically demanding as for blue-collar workers. Further, this finding could also pertain to factors such as loss of income when sicklisted, as this loss will be higher among higher salaried employees. However, a selection mechanism may be at hand in the way that professionals with high demands put on them might constitute an extremely healthy group of people, robust towards sickness absence. We believe this could be the case as concerns those working more than 50 h/week, but hardly applicable to the total sample as the criteria set for participation are fulfilled by a large part of the Swedish workforce. In this study, all the women were professionals in managerial positions with a relatively high decisionmaking capacity and there is reason to believe that the group of women reporting more than 50 h/week at work were able to organize their everyday life in such a way as to reduce household work and child care responsibilities, thereby also reducing the perception of workhome conflict. The conflict between demands perceived by men, also found in another recent study [24], might be explained by mens relatively greater participation in household activities over the last 15 years [25]. The double-exposure situation did not give rise to an increased risk of sickness absence among either men or women. This is also an interesting finding in the light of other studies examining morbidity outcomes in general population samples, where for women this situation often gives rise to excess morbidity risks [14,26]. However, for the men and women in this study, being in comparable decisionmaking positions in the labour market, the paid work seems to be so important as to guard against other stressors. Methodological considerations Our findings were based on cross-sectional, selfreported data, which means that the causal direction of the relationship between total workload and workstress variables cannot be established. No register data for sickness absence were available, which is a

Discussion This study adds to the literature on paid and unpaid work and sickness absence as it included both men and women and consisted of employees in similar work circumstances. As sickness absence rates in the general population in Sweden are much higher for women than for men, this study investigated patterns of sickness absence as related to work and home conditions and the interplay between them in a homogeneous population of highly educated men and women. The hypothesis was that gender differences would be somewhat less prominent in this group. The results indicate a pattern similar to that for the general Swedish population, with women reporting twice as many days of absence as men in the last year. However, the reported number of days of absence for both men and women was considerably less than that noted for the Swedish population [12]. Surprisingly, overtime ((50 hours/week) was found to guard not only the men but also the women against sickness absence, and a double-exposure situation did not increase the risk of sick leave in this group of highly educated employees, either for women or for men. Contrary to what is normally seen, conflict between demands from paid work and family responsibilities did not emerge as a risk factor for sickness absence for women, but it did for men. Women in the second highest work positions were vulnerable in relation to sickness absence. This could be explained within the framework of the demand control model [20], as increasing demands at work in recent years have not been balanced by improved decision-making and development opportunities for women [21,22]. Particularly in this position, women managers often feel squeezed between their superiors and subordinate staff, while mens working conditions have instead improved at this level [22]. The effect of overtime being associated with lower sickness absence has been found previously for men but not for women. However, Alfredson and colleagues have shown that women doingw10 hours of overtime a week run a greater risk of being hospitalized for myocardial infarction [23]. They hypothesized that this difference was linked to differing conditions at work with more men in high-status jobs, able to influence if and when to work overtime, while the women more often were instructed to work overtime. The differing social roles of men and women, with women shouldering the main responsibility for household work and child care, combined with the fact that women also

Workload, work stress, and sickness absence disadvantage in the sense that it might be difficult to recall accurately days of absence a year retrospectively. On the other hand, for this committed part of the workforce, days of sickness absence would possibly be remembered, as fulfilling job demands seemed to be of major importance. Furthermore, the self reports most probably included all the days of absence and not just those registered at the regional social insurance office (first week excluded at the time of data sampling). A healthy-worker effect may be at hand among those spending more than 50 hours per week in paid work, but on the other hand the analyses revealed that this was the somewhat older people where family and economic circumstances allowed much time to be spent on making a professional career. There is also a risk of response bias in that the participants who reported many sickness absence days might rate their working conditions as generally worse than those reporting fewer or no days of absence. However, women reported more days of sick leave than men, but for many of the independent variables the risk of sickness absence was higher for men, which speaks against such an effect. Furthermore, as the respondents were all white-collar workers working full time, our results are not generalizable to blue-collar workers or to those in part-time work. As the dependent variable was rather skewed, it was also tried as logarithmically transformed, but this procedure did not change the p values. Conclusion Our assumption that sickness-absence patterns would be more similar for white-collar men and women than is the case for the general population was not confirmed, as women in the study had twice as many days of absence as the men. However, the women working most hours were also the least sicklisted and assumed less responsibility for household chores. These women were mainly in top-level positions and therefore we conclude that men and women in these high-level positions seem to share household burdens more evenly, but they can also afford to employ someone to assist in the household, which is otherwise rare in Sweden. Acknowledgements This project was supported by grants to Ulf Lundberg from the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation. References

245

[1] North F, Syme SL, Feeney A, Head J, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG. Explaining socioeconomic differences in sickness absence: The Whitehall II study. Br Med J 1993;306:3615. [2] Kristensen TS. Sickness absence and work strain among Danish slaughterhouse workers: an analysis of absence from work regarded as coping behaviour. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:1527. [3] Vahtera J. Role clarity, fairness, and organizational climate as predictors of sickness absence: a prospective study in the private sector. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:42634. [4] North FM, Syme SL, Feeney A, Shipley M, Marmot M. Psychosocial work environment and sickness absence among British civil servants: The Whitehall II study. Am J Public Health 1996;86:33240. [5] Vahtera J, Kivima ki M, Pentti J, Theorell T. Effect of change in the psychosocial work environment on sickness absence: a seven year follow up of initially healthy employees. J Epidemiol Community Health 2000;54:48493. [6] Kivima ki M, Vahtera J, Thomson L, Griffiths A, et al. Psychosocial factors predicting employee sickness absence during economic decline. J Appl Psychol 1997;82:85872. kerlind I, Alexandersson K, Hensing G, Leijon M, [7] A Bjurulf P. Sex differences in absence in relation to parental status. Scand J Soc Med 1996;24:2735. [8] Feeney A, North F, Head J, Canner R, Marmot M. Socioeconomic and sex differentials in reason for sickness absence from the Whitehall II study. Occup Environ Med 1998;55:918. [9] Hemingway H, Shipley M, Stansfield S, Marmot M. Sickness absence from back pain, psychosocial work characteristics and employment grade among office workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 1997;23:1219. [10] Leijon M, Hensing G, Alexanderson K. Gender trends in sick-listing with musculoskeletal symptoms in a Swedish county during a period of rapid increase in sickness absence. Scand J Soc Med 1998;26:20413. [11] Vahtera J, Virtanen P, Kivima ki M, Pentti J. Workplace as an origin of health inequalities. J Epidemiol Community Health 1999;53:399407. [12] Sjuktalet (Sickness absence rates). Statistikinformation (www.rfv.se). Bilaga till pressmeddelande 041021. Stockholm: National Social Insurance Board (Riksfo rsa kringsverket), 2004. [13] Ja msta lld va rd (Equality in care). Huvudbeta nkande av Utredningen om bemo tande av kvinnor och ma n inom ha lso- och sjukva rden. (Report on the treatment of women and men within the health care services). Stockholm: Socialdepartementet, Statens offentliga utredningar 1996. SOU 1996;133:7594. stergren P-O. Double exposure: The combined [14] Krantz G, O impact of domestic responsibilities and job strain on common symptoms in employed Swedish women. Eur J Public Health 2001;11:41319. [15] Leijon M, Hensing G, Alexanderson K. Sickness absence due to musculoskeletal diagnoses: Association with occupational gender segregation. Scand J Public Health 2004;32:94101. [16] Kahn RL. The forms of womens work. In: Frankenhaeuser M, Lundberg U, Chesney MA, editors. Women, work and health: Stress and opportunities. New York: Plenum Press, 1991. p. 6583. [17] Ma rdberg B, Lundberg U, Frankenhaeuser M. The total workload of parents employed in white collar jobs:

246

G. Krantz & U. Lundberg

construction of a questionnaire and a scoring system. Scand J Psychol 1991;32:2339. Norusis M. Statistical package for the social sciences. Professional statistics release 6.1 (SPSS 6.1). Chicago: SPSS, 1994. Berntsson L, Lundberg U, Krantz G. Workhome interplay: gender differences in self-assessed stress, conflict and control among Swedish white-collar employees. Soc Sci Med, submitted. Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work, stress productivity and the reconstruction of working life. New York: Basic Books, 1990. stergren P-O. Do a high level of common Krantz G, O symptoms predict long spells of sickness absence in Swedish women, 40 to 50 years of age? Scand J Pubic Health 2002;30:17683. Ha renstam A. Framtidens risker i arbetslivet (Risks in future working life). In: I va ntan pa framtiden (Waiting for the future). Proceedings of the research seminar held in Umea , 1920 January 2000. Umea : National Social Insurance Offices Association, Swedish Council of Social Research, and National Social Insurance Board, 2000. p. 5169. Alfredsson L, Spetz CL, Theorell T. Type of occupation and near-future hospitalization for myocardial infarction and some other diagnoses. Int J Epidemiol 1985;14:37888. Emslie C, Hunt K, Macintyre S. Gender, workhome conflict, and morbidity amongst white-collar bank employees in the United Kingdom. Int J Behav Med 2004;11:12734. Pa tal om kvinnor och ma n, 2004 (On men and women, 2004). Statistics Sweden, Department of Demographic rebro: SCBAnalysis and Equality between the Sexes. O Tryck, 2004. p. 34. Hall EM. Double exposure: The combined impact of the home and work environments on psychosomatic strain in Swedish women and men. Int J Health Serv 1992;22: 23960.

[18]

[23]

[19]

[24]

[20]

[25]

[21]

[26]

[22]

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- 7 Habits of Highly Effective People SummaryDokument0 Seiten7 Habits of Highly Effective People SummaryJSH100Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Chemistry of The Leather IndustryDokument17 SeitenThe Chemistry of The Leather Industrymariyyun100% (3)

- Gender Differences in LeadershipDokument17 SeitenGender Differences in Leadershipmaxmunir100% (1)

- Krajewski Om9 PPT 01Dokument31 SeitenKrajewski Om9 PPT 01faizahaman8100% (1)

- Led TV in The Classroom Its Acceptability and Effectiveness in The PhilippinesDokument24 SeitenLed TV in The Classroom Its Acceptability and Effectiveness in The PhilippinesGlobal Research and Development Services100% (3)

- AI-Enhanced MIS ProjectDokument96 SeitenAI-Enhanced MIS ProjectRomali Keerthisinghe100% (1)

- Nivea Marketing PlanDokument4 SeitenNivea Marketing PlanRavena Smith80% (5)

- Holy Child Catholic School v. Hon. Patricia Sto. TomasDokument10 SeitenHoly Child Catholic School v. Hon. Patricia Sto. TomasEmir MendozaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Promising Questions and Corresponding Answers For AdiDokument23 SeitenPromising Questions and Corresponding Answers For AdiBayari E Eric100% (2)

- 134 Problem SolvingDokument17 Seiten134 Problem SolvingHoa SabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brand Building at KelloggDokument4 SeitenBrand Building at Kelloggdreamgirlrashmi0Noch keine Bewertungen

- V 36 - International Marketing For The Turkish Leather ProductsDokument13 SeitenV 36 - International Marketing For The Turkish Leather ProductsAta RehmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Internet Media TermsDokument10 SeitenInternet Media TermsmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- BusinessAdmin 2012 PDFDokument240 SeitenBusinessAdmin 2012 PDFMuslima KanwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter One: The Dynamics of Business and EconomicsDokument26 SeitenChapter One: The Dynamics of Business and EconomicsmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- JD Sport Edit PDFDokument1 SeiteJD Sport Edit PDFmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Marketing Mix - AdidasDokument2 SeitenThe Marketing Mix - AdidasPratiwi SusantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Natural DisastersDokument66 SeitenWhy Natural DisastersmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9Dokument7 Seiten9maxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Management TermsDokument71 SeitenMarketing Management TermstheresaNoch keine Bewertungen

- KingdomNomics Book 131205 PDFDokument94 SeitenKingdomNomics Book 131205 PDFsaikishore6100% (2)

- Spécial Mobile), Is A Standard Set Developed by The EuropeanDokument2 SeitenSpécial Mobile), Is A Standard Set Developed by The EuropeanmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Krajewski Chapter 13Dokument58 SeitenKrajewski Chapter 13maxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Office Design On Employees' Productivity - A Case Study of BankingDokument13 SeitenImpact of Office Design On Employees' Productivity - A Case Study of Bankingani ni musNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advertisement Important TermsDokument2 SeitenAdvertisement Important TermsmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Gender-Based Framework of The Experience of Job Insecurity and ItsDokument37 SeitenA Gender-Based Framework of The Experience of Job Insecurity and ItsmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Russia Supports Repressive Regimes in Syria and The Middle EastDokument5 SeitenWhy Russia Supports Repressive Regimes in Syria and The Middle EastmaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 CBDokument17 SeitenChapter 1 CBAnton JuniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review by Rekha ReddyDokument12 SeitenLiterature Review by Rekha ReddymaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- 27577664Dokument9 Seiten27577664maxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full 3 PDFDokument7 SeitenFull 3 PDFawaisnaseer49Noch keine Bewertungen

- Schiff CB Ce 01Dokument24 SeitenSchiff CB Ce 01maxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- The German Fibromyalgia Consumer Reports - A Cross-Sectional SurveyDokument7 SeitenThe German Fibromyalgia Consumer Reports - A Cross-Sectional SurveymaxmunirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Source (59) - Uttar Pradesh - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDokument27 SeitenSource (59) - Uttar Pradesh - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAmeet MehtaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seat Plan For Grade 11 - DiamondDokument3 SeitenSeat Plan For Grade 11 - DiamondZOSIMO PIZONNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ph.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016Dokument35 SeitenPh.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016ragvshahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humanities-A STUDY ON CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT-Kashefa Peerzada PDFDokument8 SeitenHumanities-A STUDY ON CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT-Kashefa Peerzada PDFBESTJournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 OrganizingDokument17 SeitenChapter 4 OrganizingKenjie GarqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidebook For All 2020 - 2021 PDFDokument125 SeitenGuidebook For All 2020 - 2021 PDFZegera MgendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Blue Letter 09.14.12Dokument2 SeitenBlue Letter 09.14.12StAugustineAcademyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Step1 Journey-To 271Dokument7 SeitenStep1 Journey-To 271Nilay BhattNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuitionfees 2 NdtermDokument3 SeitenTuitionfees 2 NdtermBhaskhar AnnaswamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Unregister StudentsDokument750 SeitenFinal Unregister StudentsAastha sharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knowledge Capture and CodificationDokument45 SeitenKnowledge Capture and CodificationAina Rahmah HayahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reported speech questionsDokument15 SeitenReported speech questionsLuisFer LaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityDokument2 SeitenLesson-Plan-Voc Adjs Appearance Adjs PersonalityHamza MolyNoch keine Bewertungen

- MiA Handbook - Def - MVGDokument169 SeitenMiA Handbook - Def - MVGTran Dai Nghia100% (1)

- 1a.watch, Listen and Fill The GapsDokument4 Seiten1a.watch, Listen and Fill The GapsveereshkumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesDokument12 Seiten1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesJammie Aure EsguerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5E Lesson Plan Template: TeacherDokument6 Seiten5E Lesson Plan Template: Teacherapi-515949514Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rubric PresentationDokument5 SeitenRubric PresentationLJ ValdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHAPTER 3 - The Teacher As A ProfessionDokument4 SeitenCHAPTER 3 - The Teacher As A ProfessionWindelen JarabejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Important DatesDokument6 SeitenImportant DatesKatrin KNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 1 - What Is AlgaeDokument20 SeitenLesson 1 - What Is AlgaeYanyangGongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community and Environmental HealthDokument26 SeitenCommunity and Environmental HealthMary Grace AgueteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Frameworks For Technological IntegrationDokument9 SeitenFrameworks For Technological IntegrationInjang MatinikNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 Porfolio .Dokument14 Seiten3 Porfolio .Adeline JakosalemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume of MD - Rayhanur Rahman Khan: ObjectiveDokument3 SeitenResume of MD - Rayhanur Rahman Khan: ObjectiveRayhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum 2016Dokument594 SeitenCurriculum 2016Brijesh UkeyNoch keine Bewertungen