Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Deposit Own Digests

Hochgeladen von

viva_33Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Deposit Own Digests

Hochgeladen von

viva_33Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

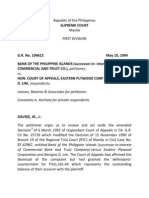

DEPOSIT A. Definition BANK OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS APPELLATE COURT and ZSHORNACK G.R. No.

L-66826 August 19, 1988 v. THE INTERMEDIATE

FACTS Rizaldy Zshornack initiated proceedings by filing in the CFI a complaint against Commercial Bank and Trust Company of the Philippines (COMTRUST) alleging four causes of action. Except for the third cause of action, the CFI ruled in favor of Zshornack. The bank appealed to the Intermediate Appellate Court which modified the CFI decision absolving the bank from liability on the fourth cause of action. Undaunted, the bank comes to this Court praying that it be totally absolved from any liability to Zshornack. Rizaldy Zshornack and his wife, Shirley Gorospe, maintained in COMTRUST, Quezon City Branch, a dollar savings account and a peso current account. An application for a dollar draft was accomplished by Virgilio V. Garcia, Assistant Branch Manager of COMTRUST Quezon City, payable to a certain Leovigilda D. Dizon in the amount of $1,000.00. Garcia indicated that the amount was to be charged to Dollar Savings Acct. No. 25-4109, the savings account of the Zshornacks; the charges for commission, documentary stamp tax and others totalling P17.46 were to be charged to Current Acct. No. 210465-29, again, the current account of the Zshornacks. On the same date, COMTRUST, under the signature of Virgilio V. Garcia, issued a check payable to the order of Leovigilda D. Dizon in the sum of US $1,000 drawn on the Chase Manhattan Bank, New York, with an indication that it was to be charged to Dollar Savings Acct. No. 25-4109. When Zshornack noticed the withdrawal of US$1,000.00 from his account, he demanded an explanation from the bank. In answer, COMTRUST claimed that the peso value of the withdrawal was given to Atty. Ernesto Zshornack, Jr., brother of Rizaldy when he (Ernesto) encashed with COMTRUST a cashier's check for P8,450.00 issued by the Manila Banking Corporation payable to Ernesto. ISSUE Whether petitioner bank is liable to Zshornack. No. Zshornack cannot recover under the second cause of action.

RATIO This Court finds no reason to disturb the ruling of both the trial court and the Appellate Court on the first cause of action. Petitioner must be held liable for the unauthorized withdrawal of US$1,000.00 from private respondent's dollar account. As to the second cause of action: The bank is deemed to have admitted not only Garcia's authority, but also the bank's power, to enter into the contract in question. The document which embodies the contract states that the US$3,000.00 was received by the bank for safekeeping. The subsequent acts of the parties also show that the intent of the parties was really for the bank to safely keep the dollars and to return it to Zshornack at a later time. The above arrangement is that contract defined under Article 1962, New Civil Code: a deposit is constituted from the moment a person receives a thing belonging to another, with the obligation of safely keeping it and of returning the same. If the safekeeping of the thing delivered is not the principal purpose of the contract, there is no deposit but some other contract. Note that the object of the contract between Zshornack and COMTRUST was foreign exchange. Hence, the transaction was covered by Central Bank Circular No. 20, Restrictions on Gold and Foreign Exchange Transactions. The parties did not intended to sell the US dollars to the Central Bank within one business day from receipt. Otherwise, the contract of depositum would never have been entered into at all. Since the mere safekeeping of the greenbacks, without selling them to the Central Bank within one business day from receipt, is a transaction which is not authorized by CB Circular No. 20, it must be considered as one which falls under the general class of prohibited transactions. Hence, pursuant to Article 5 of the Civil Code, it is void, having been executed against the provisions of a mandatory/prohibitory law. More importantly, it affords neither of the parties a cause of action against the other. "When the nullity proceeds from the illegality of the cause or object of the contract, and the act constitutes a criminal offense, both parties being in pari delicto, they shall have no cause of action against each other. . ." [Art. 1411, New Civil Code.] The only remedy is one on behalf of the State to prosecute the parties for violating the law.

Credit Transactions - Deposit

B. Nature and Characteristics BANK OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS (successor-in- interest of COMMERCIAL AND TRUST CO.) v. HON. COURT OF APPEALS, EASTERN PLYWOOD CORP. and BENIGNO D. LIM G.R. No. 104612 May 10, 1994 FACTS Private respondents Eastern Plywood Corporation (Eastern) and Benigno D. Lim (Lim), an officer and stockholder of Eastern, held at least one joint bank account ("and/or" account) with the Commercial Bank and Trust Co. (CBTC). A joint checking account ("and" account) with Lim in the amount of P120,000.00 was opened by Mariano Velasco with funds withdrawn from the account of Eastern and/or Lim. Velasco died. At the time of his death, the outstanding balance of the account stood at P662,522.87. On 5 May 1977, by virtue of an Indemnity Undertaking executed by Lim for himself and as President and General Manager of Eastern, one-half of this amount was provisionally released and transferred to one of the bank accounts of Eastern with CBTC. Eastern obtained a loan of P73,000.00 from CBTC as "Additional Working Capital." The loan was payable on demand with interest at 14% per annum. For this loan, Eastern issued on the same day a negotiable promissory note for P73,000.00 payable on demand to the order of CBTC with interest at 14% per annum. The note was signed by Lim both in his own capacity and as President and General Manager of Eastern. In addition, Eastern and Lim, and CBTC signed another document entitled "Holdout Agreement," also dated 18 August 1978, wherein it was stated that "as security for the Loan [Lim and Eastern] have offered [CBTC] and the latter accepts a holdout on said [Current Account No. 2310-011-42 in the joint names of Lim and Velasco] to the full extent of their alleged interests therein as these may appear as a result of final and definitive judicial action or a settlement between and among the contesting parties thereto." In the meantime, a case for the settlement of Velasco's estate was filed. In the said case, the whole balance of P331,261.44 in the aforesaid joint account of Velasco and Lim was being claimed as part of Velasco's estate. The intestate court granted the urgent motion of the heirs of Velasco to withdraw the deposit under the joint account of Lim and Velasco and authorized the heirs to divide among themselves the amount withdrawn.

CBTC was merged with BPI. BPI filed with the RTC a complaint against Lim and Eastern demanding payment of the promissory note for P73,000.00. o Defendants Lim and Eastern, in turn, filed a counterclaim against BPI for the return of the balance in the disputed account subject of the Holdout Agreement and the interests thereon after deducting the amount due on the promissory note. Trial Court: dismissed the complaint because BPI failed to make out its case. It ruled that "the promissory note in question is subject to the 'hold-out' agreement," and that based on this agreement, "it was the duty of BPI to debit the account of the defendants under the promissory note to set off the loan even though the same has no fixed maturity." o As to the counterclaim the court denied it because the "said claim cannot be awarded without disturbing the resolution" of the intestate court. CA: affirmed the TCs decision. As to the counter claim, in its amended decision it ruled that the settlement of Velasco's estate had nothing to do with the claim of the defendants for the return of the balance of their account with CBTC/BPI as they were not privy to that case, and that the defendants, as depositors of CBTC/BPI, are the latter's creditors, hence, CBTC/BPI should have protected the defendants' interest in Sp. Proc. No. 8959 when the said account was claimed by Velasco's estate. It then ordered BPI "to pay defendants the amount of P331,261.44 representing the outstanding balance in the bank account of defendants." BPI filed the instant petition alleging therein that the Holdout Agreement in question was subject to a suspensive condition: that the "P331,261.44 shall become a security for respondent Lim's promissory note only if respondents' Lim and Eastern Plywood Corporation's interests to that amount are established as a result of a final and definitive judicial action or a settlement between and among the contesting parties thereto." Private respondents Eastern and Lim dispute the "suspensive condition" argument of the petitioner. The money deposited in the joint account of Velasco and Lim came from Eastern and Lim's own account as a finding that the money deposited in the joint account of Lim and Velasco "rightfully belonged to Eastern Plywood Corporation and/or Benigno Lim." And because the latter are the rightful owners of the money in question, the suspensive condition does not find any application in this case and the bank had the duty to set off this deposit with the loan. o They add that the ruling of the lower court that they own the disputed amount is the final and definitive judicial action

Credit Transactions - Deposit

required by the Holdout Agreement; hence, the petitioner can only hold the amount of P73,000.00 representing the security required for the note and must return the rest. ISSUES (1) Whether BPI can demand payment of the loan of P73,000.00 despite the existence of the Holdout Agreement. Yes. (2) Whether BPI is still liable to the private respondents on the account subject of the Holdout Agreement after its withdrawal by the heirs of Velasco. Yes. RATIO (1) Yes. BPI can demand payment of the loan despite the existence of the Holdout Agreement. The collection suit of BPI is based on the promissory note for P73,000.00. BPI was not a holder in due course because the note was not indorsed to BPI by the payee, CBTC. It acquired the note from CBTC by the contract of merger or sale between the two banks. BPI, therefore, took the note subject to the Holdout Agreement. In the interpretation of the Holdout Agreement, it is clear from par. 2 thereof that CBTC, or BPI as its successor-in-interest, had every right to demand that Eastern and Lim settle their liability under the promissory note. o It cannot be compelled to retain and apply the deposit in Lim and Velasco's joint account to the payment of the note. o What the agreement conferred on CBTC was a power, not a duty. Generally, a bank is under no duty or obligation to make the application. To apply the deposit to the payment of a loan is a privilege, a right of set-off which the bank has the option to exercise. Also, par. 5 of the Holdout Agreement itself states that notwithstanding the agreement, CBTC was not in any way precluded from demanding payment from Eastern and from instituting an action to recover payment of the loan. o What it provides is an alternative, not an exclusive, method of enforcing its claim on the note. When it demanded payment of the debt directly from Eastern and Lim, BPI had opted not to exercise its right to apply part of the deposit subject of the Holdout Agreement to the payment of the promissory note for P73,000.00. (2) Yes. The counterclaim of Eastern and Lim for the return of the P331,261.44 was equivalent to a demand that they be allowed to withdraw their deposit with the bank. Article 1980 of the Civil Code expressly provides that "fixed, savings,

and current deposits of money in banks and similar institutions shall be governed by the provisions concerning simple loan." Bank deposits are in the nature of irregular deposits; they are really loans because they earn interest. The relationship then between a depositor and a bank is one of creditor and debtor. The deposit under the questioned account was an ordinary bank deposit; hence, it was payable on demand of the depositor. The account was proved and established to belong to Eastern even if it was deposited in the names of Lim and Velasco. As the real creditor of the bank, Eastern has the right to withdraw it or to demand payment thereof. BPI cannot be relieved of its duty to pay Eastern simply because it already allowed the heirs of Velasco to withdraw the whole balance of the account. The petitioner should not have allowed such withdrawal because it had admitted in the Holdout Agreement the questioned ownership of the money deposited in the account. Moreover, the order of the court in Sp. Proc. No. 8959 merely authorized the heirs of Velasco to withdraw the account. BPI was not specifically ordered to release the account to the said heirs; hence, it was under no judicial compulsion to do so. o The authorization given to the heirs of Velasco cannot be construed as a final determination or adjudication that the account belonged to Velasco. o The determination by a probate court of whether that property is included in the estate of a deceased is merely provisional in character and cannot be the subject of execution. Because the ownership of the deposit remained undetermined, BPI, as the debtor with respect thereto, had no right to pay to persons other than those in whose favor the obligation was constituted or whose right or authority to receive payment is indisputable. The payment of the money deposited with BPI that will extinguish its obligation to the creditor-depositor is payment to the person of the creditor or to one authorized by him or by the law to receive it. Payment made by the debtor to the wrong party does not extinguish the obligation as to the creditor who is without fault or negligence, even if the debtor acted in utmost good faith and by mistake as to the person of the creditor, or through error induced by fraud of a third person. o The payment then by BPI to the heirs of Velasco, even if done in good faith, did not extinguish its obligation to the true depositor, Eastern.

Credit Transactions - Deposit

MANUEL M. SERRANO v. CENTRAL BANK OF THE PHILIPPINES; OVERSEAS BANK OF MANILA; EMERITO M. RAMOS, SUSANA B. RAMOS, EMERITO B. RAMOS, JR., JOSEFA RAMOS DELA RAMA, HORACIO DELA RAMA, ANTONIO B. RAMOS, FILOMENA RAMOS LEDESMA, RODOLFO LEDESMA, VICTORIA RAMOS TANJUATCO, and TEOFILO TANJUATCO G.R. No. L-30511 February 14, 1980 FACTS This is a Petition for mandamus and prohibition, with preliminary injunction, that seeks the establishment of joint and solidary liability to the amount of 350,000, with interest, against respondent Central Bank of the Philippines and Overseas Bank of Manila and its stockholders, on the alleged failure of the Overseas Bank of Manila to return the time deposits made by petitioner and assigned to him, on the ground that respondent Central Bank failed in its duty to exercise strict supervision over respondent Overseas Bank of Manila to protect depositors and the general public. Petitioner made a time deposit, for one year with 6% interest, of P150,000.00 with the respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Concepcion Maneja also made a time deposit, for one year with 6 12% interest, of P200,000.00 with the same respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Concepcion Maneja, married to Felixberto M. Serrano, assigned and conveyed to petitioner Manuel M. Serrano, her time deposit of P200,000.00 with respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Notwithstanding series of demands for encashment of the aforementioned time deposits from the respondent Overseas Bank of Manila, not a single one of the time deposit certificates was honored by respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Respondent Central Bank admits that it is charged with the duty of administering the banking system of the Republic and it exercises supervision over all doing business in the Philippines, but denies the petitioner's allegation that the Central Bank has the duty to exercise a most rigid and stringent supervision of banks, implying that respondent Central Bank has to watch every move or activity of all banks, including respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Respondent Central Bank likewise denied that a constructive trust was created in favor of petitioner and his predecessor in interest Concepcion Maneja when their time deposits were made in 1966 and 1967 with the respondent Overseas Bank of Manila as during that time the latter was not an insolvent bank and its operation as a banking institution was being salvaged by the respondent Central Bank. Respondent Central Bank avers no knowledge of petitioner's claim

that the properties given by respondent Overseas Bank of Manila as additional collaterals to respondent Central Bank of the Philippines for the former's overdrafts and emergency loans were acquired through the use of depositors' money, including that of the petitioner and Concepcion Maneja. In G.R. No. L-29362, entitled "Emerita M. Ramos, et al. vs. Central Bank of the Philippines," a case was filed by the petitioner Ramos, wherein respondent Overseas Bank of Manila sought to prevent respondent Central Bank from closing, declaring the former insolvent, and liquidating its assets. o Petitioner Manuel Serrano in this case, filed a motion to intervene in G.R. No. L-29352, on the ground that Serrano had a real and legal interest as depositor of the Overseas Bank of Manila in the matter in litigation in that case. o Respondent Central Bank in G.R. No. L-29352 opposed petitioner Manuel Serrano's motion to intervene in that case, on the ground that his claim as depositor of the Overseas Bank of Manila should properly be ventilated in the Court of First Instance. o TC: Denied petitioners Motion to Intervene. This court rendered a decision in favor of respondent Overseas Bank of Manila. Because of the above decision, petitioner in this case filed a motion for judgment in this case, praying for a decision on the merits, adjudging respondent Central Bank jointly and severally liable with respondent Overseas Bank of Manila to the petitioner for the P350,000 time deposit made with the latter bank, with all interests due therein; and declaring all assets assigned or mortgaged by the respondents Overseas Bank of Manila and the Ramos groups in favor of the Central Bank as trust funds for the benefit of petitioner and other depositors.

ISSUE Whether there was a constructive trust created in petitioners favor when the respondent Overseas Bank of Manila increased its collaterals in favor of respondent Central Bank for the former's overdrafts and emergency loans, since these collaterals were acquired by the use of depositors' money. No. RATIO By the very nature of the claims and causes of action against respondents, they in reality are recovery of time deposits plus interest from respondent Overseas Bank of Manila, and recovery of damages against respondent Central Bank for its alleged failure to strictly supervise the acts of the other respondent Bank and protect

Credit Transactions - Deposit

the interests of its depositors by virtue of the constructive trust created when respondent Central Bank required the other respondent to increase its collaterals for its overdrafts said emergency loans, said collaterals allegedly acquired through the use of depositors money. These claims should be ventilated in the CFI of proper jurisdiction. Claims of these nature are not proper in actions for mandamus and prohibition as there is no shown clear abuse of discretion by the Central Bank in its exercise of supervision over the other respondent Overseas Bank of Manila, and if there was, petitioner here is not the proper party to raise that question, but rather the Overseas Bank of Manila. Furthermore, both parties overlooked one fundamental principle in the nature of bank deposits when the petitioner claimed that there should be created a constructive trust in his favor when the respondent Overseas Bank of Manila increased its collaterals in favor of respondent Central Bank for the former's overdrafts and emergency loans, since these collaterals were acquired by the use of depositors' money. Bank deposits are in the nature of irregular deposits. They are really loans because they earn interest. All kinds of bank deposits, whether fixed, savings, or current are to be treated as loans and are to be covered by the law on loans. Current and savings deposit are loans to a bank because it can use the same. The petitioner here in making time deposits that earn interests with respondent Overseas Bank of Manila was in reality a creditor of the respondent Bank and not a depositor. The respondent Bank was in turn a debtor of petitioner. Failure of he respondent Bank to honor the time deposit is failure to pay its obligation as a debtor and not a breach of trust arising from depositary's failure to return the subject matter of the deposit.

DISPOSITIVE: the petition is dismissed for lack of merit, with costs against petitioner. LUA KIAN v. MANILA RAILROAD COMPANY and MANILA PORT SERVICE G.R. No. L-23033 January 5, 1967 FACTS The present suit was filed by Lua Kian against the Manila Railroad Co. and Manila Port Service for the recovery of the invoice value of imported evaporated "Carnation" milk alleged to have been undelivered.

Defendant Manila Port Service as a subsidiary of defendant Manila Railroad Company operated the arrastre service at the Port of Manila under and pursuant to the Management Contract entered into by and between the Bureau of Customs and defendant Manila Port Service. Plaintiff Lua Kian imported 2,000 cases of Carnation Milk from the Carnation Company of San Francisco, California, and shipped on Board SS "GOLDEN BEAR" per Bill of Lading No. 17. o Out of the aforesaid shipment of 2,000 cases of Carnation Milk per Bill of Lading No. 17, only 1,829 cases marked `LUA KIAN 1458' were discharged from the vessel SS `GOLDEN BEAR' and received by defendant Manila Port Service per pertinent tally sheets issued by the said carrying vessel. Discharged from the same vessel on the same date unto the custody of defendant Manila Port Service were 3,171 cases of Carnation Milk marked "CEBU UNITED 4860-PH-MANILA" consigned to Cebu United Enterprises, per Bill of Lading No. 18. Defendant Manila Port Service delivered to the plaintiff thru its broker, Ildefonso Tionloc, Inc. 1,913 cases of Carnation Milk marked "LUA KIAN 1458" per pertinent gate passes and broker's delivery receipts. A provisional claim was filed by the consignee's broker for and in behalf of the plaintiff with defendant Manila Port Service. The invoice value of the 87 cases of Carnation Milk claimed by the plaintiff to have been short-delivered by defendant Manila Port Service is P1,183.11 while the invoice value of the 87 cases of Carnation Milk claimed by the defendant Manila Port Service to have been over-delivered by it to plaintiff is P1,130.65. The 1,913 cases of Carnation mentioned in paragraph 5 hereof were taken by the broker at Pier 13, Shed 3, sometime in February, 1960, where at the time, there were stored therein, aside from the shipment involved herein, 1000 cases of Carnation Milk bearing the same marks and also consigned to plaintiff Lua Kian but had been discharged from SS `STEEL ADVOCATE' and covered by Bill of Lading No. 11. Lua Kian as consignee thereof filed a claim for short-delivery against defendant Manila Port Service, and said defendant Manila Port Service paid Lua Kian plaintiff herein, P750.00 in settlement of its claim. CFI: ruled that 1,829 cases marked Lua Kian (171 cases less than the 2,000 cases indicated in the bill of lading and 3,171 cases marked "Cebu United" (171 cases over the 3,000 cases in the bill of lading were discharged to the Manila Port Service. o Considering that Lua Kian and Cebu United Enterprises were the only consignees of the shipment of 5,000 cases of

Credit Transactions - Deposit

"Carnation" milk, it found that of the 3,171 cases marked "Cebu United", 171 should have been delivered to Lua Kian. o Inasmuch as the defendant Manila Port Service actually delivered 1,913 cases to plaintiff, which is only 87 cases short of 2,000 cases as per bill of lading the former was ordered to pay Lua Kian the sum of P1,183.11 representing such shortage of 87 cases, with legal interest from the date of the suit, plus P500 as attorney's fees. Defendants appealed to the Supreme Court and contend that they should not be made to answer for the undelivered cases of milk, insisting that Manila Port Service was bound to deliver only 1,829 cases to Lua Kian and that it had there before in fact overdelivered to the latter.

consignment to Lua Kian was 171 cases less than the 2,000 in the bill of lading, should have been sufficient reason for the defendant Manila Port Service to withhold the goods pending determination of their rightful ownership. With respect to the attorney's fees awarded below, this Court notices that the same is about 50% of the litigated amount of P1,183.11. Attorneys fees was decreased to P300.00.

C. Rights and Obligations of Depositor and Depositary ANGEL JAVELLANA v. JOSE LIM, ET AL. G.R. No. 4015 August 24, 1908 FACTS Defendants executed a document in favor of plaintiff-appellee wherein it states that they have received, as a deposit, without interest, money from plaintiff-appellee and agreed upon a date when they will return the money. Upon the stipulated due date, defendants asked for an extension to pay and binding themselves to pay 15% interest per annum on the amount of their indebtedness, to which the plaintiff-appellee acceded. The defendants were not able to pay the full amount of their indebtedness notwithstanding the request made by plaintiff-appellee. The lower court ruled in favor of plaintiffappellee for the recovery of the amount due. ISSUE Whether the agreement entered into by the parties is one of loan or of deposit. Contract of loan. RATIO The document executed was a contract of loan. Where money, consisting of coins of legal tender, is deposited with a person and the latter is authorized by the depositor to use and dispose of the same, the agreement is not a contract of deposit, but a loan. A subsequent agreement between the parties as to interest on the amount said to have been deposited, because the same could not be returned at the time fixed therefor, does not constitute a renewal of an agreement of deposit, but it is the best evidence that the original contract entered into between therein was for a loan under the guise of a deposit.

ISSUE Whether defendant Manila Port Service is liable for the undelivered cases of Carnation milk to petitioner due to improper marking. Yes. RATIO The bill of lading in favor of Cebu United Enterprises indicated that only 3,000 cases were due to said consignee, although 3,171 cases were marked in its favor. Lua Kian whose bill of lading on the other hand indicated that it should receive 171 cases more. The legal relationship between an arrastre operator and the consignee is akin to that of a depositor and warehouseman. As custodian of the goods discharged from the vessel, it was defendant arrastre operator's duty, like that of any ordinary depositary, to take good care of the goods and to turn them over to the party entitled to their possession. o The said defendant should have withheld delivery because of the discrepancy between the bill of lading and the markings and conducted its own investigation, not unlike that under Section 18 of the Warehouse Receipts Law, or called upon the parties, to interplead, such as in a case under Section 17 of the same law, in order to determine the rightful owner of the goods. o It is true that Section 12 of the Management Contract exempts the arrastre operator from responsibility for misdelivery or non-delivery due to improper or insufficient marking. It cannot however excuse the defendant from liability in this case because the bill of lading showed that only 3,000 cases were consigned to Cebu United Enterprises. The fact that the excess of 171 cases were marked for Cebu United Enterprises and that the

Credit Transactions - Deposit

SILVESTRA BARON v. PABLO DAVID and GUILLERMO BARON v. PABLO DAVID G.R. Nos. L-26948 and L-26949 October 8, 1927 FACTS The defendant owns a rice mill, which was well patronized by the rice growers of the vicinity. On January 17, 1921, a fire occurred that destroyed the mill and its contents, and it was some time before the mill could be rebuilt and put in operation again. Silvestra Baron (P1) and Guillermo Baron (P2) each filed an action for the recovery of the value of palay from the defendant (D), alleged that: o The palay have been sold by both plaintiffs to the defendant in the year 1920. o Palay was delivered to defendant at his special request, with a promise of compensation at the highest price per cavan. D claims that the palay was deposited subject to future withdrawal by the depositors or to some future sale, which was never effected. Defendant also contended that in order for the plaintiffs to recover, it is necessary that they should be able to establish that the plaintiffs' palay was delivered in the character of a sale, and that if, on the contrary, the defendant should prove that the delivery was made in the character of deposit, the defendant should be absolved. ISSUE Whether there was a deposit? No. RATIO Art. 1978. When the depositary has permission to use the thing deposited, the contract loses the concept of a deposit and becomes a loan or commodatum, except where safekeeping is still the principal purpose of the contract. The permission shall not be presumed, and its existence must be proved. The case does not depend precisely upon this explicit alternative; for even supposing that the palay may have been delivered in the character of deposit, subject to future sale or withdrawal at plaintiffs' election, nevertheless if it was understood that the defendant might mill the palay and he has in fact appropriated it to his own use, he is of course bound to account for its value. In this connection we wholly reject the defendant's pretense that the palay delivered by the plaintiffs or any part of it was actually consumed in the fire of January, 1921. Nor is the liability of the defendant in any wise affected by the circumstance that, by a custom prevailing among rice millers in this country, persons placing palay

with them without special agreement as to price are at liberty to withdraw it later, proper allowance being made for storage and shrinkage, a thing that is sometimes done, though rarely. SPOUSES TIRSO I. VINTOLA and LORETO DY VINTOLA v. INSULAR BANK OF ASIA AND AMERICA G.R. No. 73271 May 29, 1987 FACTS This case was appealed to the IAC which, however, certified the same to this Court, the issue involved being purely legal. Spouses Tirso and Loreta Vintola doing business under the name and style "Dax Kin International," engaged in the manufacture of raw sea shells into finished products, applied for and were granted a domestic letter of credit by the Insular Bank of Asia and America (IBAA), Cebu City, in the amount of P40,000.00. The Letter of Credit authorized the bank to negotiate for their account drafts drawn by their supplier, one Stalin Tan, on Dax Kin International for the purchase of puka and olive seashells. In consideration thereof, the VINTOLAS, jointly and severally, agreed to pay the bank "at maturity, in Philippine currency, the equivalent, of the aforementioned amount or such portion thereof as may be drawn or paid, upon the faith of the said credit together with the usual charges." On the same day, August 20, 1975, having received from Stalin Tan the puka and olive shells worth P40,000.00, the VINTOLAS executed a Trust Receipt agreement with IBAA, Cebu City. o Under that Agreement, the VINTOLAS agreed to hold the goods in trust for IBAA as the "latter's property with liberty to sell the same for its account, " and "in case of sale" to turn over the proceeds as soon as received to (IBAA) the due date indicated in the document was October 19, 1975. Having defaulted on their obligation, IBAA demanded payment from the VINTOLAS in a letter dated January 1, 1976. The VINTOLAS, who were unable to dispose of the shells, responded by offering to return the goods. IBAA refused to accept the merchandise, and due to the continued refusal of the VINTOLAS to make good their undertaking, IBAA charged them with Estafa for having misappropriated, misapplied and converted for their own personal use and benefit the aforesaid goods. During the trial of the criminal case the VINTOLAS turned over the seashells to the custody of the Trial Court. CFI: acquitted the VINTOLAS of the crime charged, after finding that the element of misappropriation or conversion was inexistent.

Credit Transactions - Deposit

Finally, it should be mentioned that under the trust receipt, in the event of default and/or non-fulfillment on the part of the accused of their undertaking, the bank is entitled to take possession of the goods or to recover its equivalent value together with the usual charges. In either case, the remedy of the Bank is civil and not criminal in nature... Shortly thereafter, IBAA commenced the present civil action to recover the value of the goods before the Regional Trial Court of Cebu. RTC: Holding that the complaint was barred by the judgment of acquittal in the criminal case, said Court dismissed the complaint. However, on IBAA's motion, the Court granted reconsideration and: (1) ordered defendants jointly and severally to pay the plaintiff the sum of P72,982.27, plus interest of 14% per annum and service charge of 1% per annum computed from judicial demand and until the obligation is fully paid; (2) Ordered defendants jointly and severally to pay attorney's fees to the plaintiff in the sum of P4,000.00, plus costs of the suit. The VINTOLAS take the position that their obligation to IBAA has been extinguished inasmuch as, through no fault of their own, they were unable to dispose of the seashells, and that they have relinquished possession thereof to the IBAA, as owner of the goods, by depositing them with the Court. o

binds himself to hold the designated goods, documents or instruments in trust for the entruster and to sell or otherwise dispose of the goods, documents or instrument thereof to the extent of the amount owing to the entruster or as appears in the trust receipt or the goods, documents or instruments themselves if they are unsold or not otherwise disposed of, in accordance with the terms and conditions specified in the trust receipt, or for other purposes substantially equivalent to any one of the following: 1. In the case of goods or documents, (a) to sell the goods or procure their sale... A trust receipt, therefore, is a security agreement, pursuant to which a bank acquires a "security interest" in the goods. "It secures an indebtedness and there can be no such thing as security interest that secures no obligation." As defined in our laws: (h) "Security Interest" means a property interest in goods, documents or instruments to secure performance of some obligations of the entrustee or of some third persons to the entruster and includes title, whether or not expressed to be absolute, whenever such title is in substance taken or retained for security only. As elucidated in Samo vs. People "a trust receipt is considered as a security transaction intended to aid in financing importers and retail dealers who do not have sufficient funds or resources to finance the importation or purchase of merchandise, and who may not be able to acquire credit except through utilization, as collateral of the merchandise imported or purchased." Contrary to the allegation of the VINTOLAS, IBAA did not become the real owner of the goods. It was merely the holder of a security title for the advances it had made to the VINTOLAS The goods the VINTOLAS had purchased through IBAA financing remain their own property and they hold it at their own risk. The trust receipt arrangement did not convert the IBAA into an investor; the latter remained a lender and creditor. ... For the bank has previously extended a loan which the L/C represents to the importer, and by that loan, the importer should be the real owner of the goods. If under the trust receipt, the bank is made to appear as the owner, it was but an artificial expedient, more of a legal fiction than fact, for if it were so, it could dispose of the goods in any manner it wants, which it cannot do, just to give consistency with the purpose of the trust receipt of giving a stronger security for the loan obtained by the importer. To consider the bank as the true owner from the inception of the transaction would be to

ISSUE Whether or not the obligation of spouses was extinguished by the surrender of the goods. No. RATIO The foregoing submission overlooks the nature and mercantile usage of the transaction involved. A letter of credit-trust receipt arrangement is endowed with its own distinctive features and characteristics. Under that set-up, a bank extends a loan covered by the Letter of Credit, with the trust receipt as a security for the loan. In other words, the transaction involves a loan feature represented by the letter of credit, and a security feature, which is in the covering trust receipt. Thus, Section 4 of P.D. No. 115 defines a trust receipt transaction as: ... any transaction by and between a person referred to in this Decree as the entruster, and another person referred to in this Decree as the entrustee, whereby the entruster, who owns or holds absolute title or security interests over certain specified goods, documents or instruments, releases the same to the possession of the entrustee upon the latter's execution and delivery to the entruster of a signed document called a "trust receipt" wherein the entrustee

Credit Transactions - Deposit

disregard the loan feature thereof! Since the IBAA is not the factual owner of the goods, the VINTOLAS cannot justifiably claim that because they have surrendered the goods to IBAA and subsequently deposited them in the custody of the court, they are absolutely relieved of their obligation to pay their loan because of their inability to dispose of the goods. o The fact that they were unable to sell the seashells in question does not affect IBAA's right to recover the advances it had made under the Letter of Credit. The foregoing premises considered, it follows that the acquittal of the VINTOLAS in the Estafa case is no bar to the institution of a civil action for collection. It is inaccurate for the VINTOLAS to claim that the judgment in the Estafa case had declared that the facts from which the civil action might arise, did not exist, for, it will be recalled that the decision of acquittal expressly declared that "the remedy of the Bank is civil and not criminal in nature." This amounts to a reservation of the civil action in IBAA's favor, for the Court would not have dwelt on a civil liability that it had intended to extinguish by the same decision. The VINTOLAS are liable ex contractu for breach of the Letter of Credit Trust Receipt, whether they did or they did not "misappropriate, misapply or convert" the merchandise as charged in the criminal case. Their civil liability does not arise ex delicto, the action for the recovery of which would have been deemed instituted with the criminal-action (unless waived or reserved) and where acquittal based on a judicial declaration that the criminal acts charged do not exist would have extinguished the civil action. o Rather, the civil suit instituted by IBAA is based ex contractu and as such is distinct and independent from any criminal proceedings and may proceed regardless of the result of the latter.

personal use and benefit. Continental Bank filed a complaint for estafa against Sia. The trial court and CA ruled against Sia.

ISSUE Whether or not Sia, acting as President of MMCP, may be held liable for estafa. No. Sia was acquitted. CA decision is reversed. RATIO Ver. 1 An officer of a corporation can be held criminally liable for acts or omissions done in behalf of the corporation only where the law directly requires the corporation to do an act in a given manner. In he absence of a law making a corporate officer liable for a criminal offense committed by the corporation, the existence of the criminal liability of he former may not be said to be beyond doubt. Hence in the absence of an express provision of law making Sia liable for the offense done by MMCP of which he is President, as in fact there is no such provision under the Revised Penal Code, Sia cannot be said to be liable for estafa. RATIO Ver. 2 The case of People vs. Tan Boon Kong (54 Phil. 607) provides for the general principle that for crimes committed by a corporation, the responsible officers thereof would personally bear the criminal liability as a corporation is an artificial person, an abstract being. However, the Court ruled that such principle is not applicable in this case because the act alleged to be a crime is not in the performance of an act directly ordained by law to be performed by the corporation. The act is imposed by agreement of parties, as a practice observed in the usual pursuit of a business or a commercial transaction. The offense may arise, if at all, from the peculiar terms and condition agreed upon by the parties to the transaction, not by direct provision of the law. In the absence of an express provision of law making the petitioner liable for the criminal offense committed by the corporation of which he is a president as in fact there is no such provisions in the Revised Penal Code under which petitioner is being prosecuted, the existence of a criminal liability on his part may not be said to be beyond any doubt. In all criminal prosecutions, the existence of criminal liability for which the accused is made answerable must be clear and certain. Further, the civil liability imposed by the trust receipt is exclusively on the Metal Company. Speaking of such liability alone, the petitioner was never intended to be equally liable as the corporation. Without being made so liable personally as the corporation is, there would then be no basis for holding him criminally liable, for any violation of the trust receipt.

JOSE O. SIA v. THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES G.R. No. L-30896 April 28, 1983 FACTS Jose Sia, president and GM of Metal Manufacturing Company of the Phil., on behalf of said company, obtained delivery of 150 cold rolled steel sheets valued at P71,023.60 under a trust receipt agreement. Said sheets were consigned to the Continental Bank, under the express obligation on the part of Sia of holding the sheets in trust and selling them and turning over the proceeds to the bank. Sia, however, allegedly failed and refused to return the sheets or account for the proceeds thereof if sold, converting it to his own

Credit Transactions - Deposit

RAMON GONZALES v. GO TIONG and LUZON SURETY CO., INC. G.R. No. L-11776 August 30, 1958 FACTS Go Tiong (respondent) owned a rice mill and warehouse, located in Pangasinan. Thereafter, he obtained a license to engage in the business of a bonded warehouseman. Subsequently, respondent Tiong executed a Guaranty Bond with the Luzon Surety Co to secure the performance of his obligations as such bonded warehouseman, in the sum of P18,334, in case he was unable to return the same. Afterwards, respondent Tiong insured the warehouse and the palay deposited therein with the Alliance Surety and Insurance Company. But prior to the issuance of the license to Respondent, he had on several occasions received palay for deposit from Plaintiff Gonzales, totaling 368 sacks, for which he issued receipts. After he was licensed as a bonded warehouseman, Go Tiong again received various deliveries of palay from Plaintiff, totaling 492 sacks, for which he issued the corresponding receipts, all the grand total of 860 sacks, valued at P8,600 at the rate of P10 per sack. Noteworthy is that the receipts issued by Go Tiong to the Plaintiff were ordinary receipts, not the "warehouse receipts" defined by the Warehouse Receipts Act (Act No. 2137). On or about March 15, 1953, Plaintiff demanded from Go Tiong the value of his deposits in the amount of P8,600, but he was told to return after two days, which he did, but Go Tiong again told him to come back. A few days later, the warehouse burned to the ground. Before the fire, Go Tiong had been accepting deliveries of palay from other depositors and at the time of the fire, there were 5,847 sacks of palay in the warehouse, in excess of the 5,000 sacks authorized under his license. After the burning of the warehouse, the depositors of palay, including Plaintiff, filed their claims with the Bureau of Commerce. However, according to the decision of the trial court, nothing came from Plaintiff's efforts to have his claim paid. Thereafter, Gonzales filed the present action against Go Tiong and the Luzon Surety for the sum of P8,600, the value of his palay, with legal interest, damages in the sum of P5,000 and P1,500 as attorney's fees. While the case was pending in court, Gonzales and Go Tiong entered into a contract of amicable settlement to the effect that upon the settlement of all accounts due to him by Go Tiong, he, Gonzales, would have all actions pending against Go Tiong dismissed.

Inasmuch as Go Tiong failed to settle the accounts, Gonzales prosecuted his court action. ISSUE Whether or not Plaintiffs claim is governed by the Bonded Warehouse Act due to Go Tiongs act of issuing to the former ordinary receipts, not warehouse receipts. Yes. SC ruled in plaintiffs favor. RATIO Act No. 3893 provides that any deposit made with Respondent Tiong as a bonded warehouseman must necessarily be governed by the provisions of Act No. 3893. The kind or nature of the receipts issued by him for the deposits is not very material much less decisive since said provisions are not mandatory and indispensable. Under Section 1 of the Warehouse Receipts Act, the issuance of a warehouse receipt in the form provided by it is merely permissive and directory and not obligatory. . "Receipt", under this section, can be construed as any receipt issued by a warehouseman for commodity delivered to him. As the trial court well observed, as far as Go Tiong was concerned, the fact that the receipts issued by him were not "quedans" is no valid ground for defense because he was the principal obligor. Furthermore, as found by the trial court, Go Tiong had repeatedly promised Plaintiff to issue to him "quedans" and had assured him that he should not worry; and that Go Tiong was in the habit of issuing ordinary receipts (not "quedans") to his depositors. Furthermore, Section 7 of said law provides that as long as the depositor is injured by a breach of any obligation of the warehouseman, which obligation is secured by a bond, said depositor may sue on said bond. In other words, the surety cannot avoid liability from the mere failure of the warehouseman to issue the prescribed receipt.

CONSOLIDATED TERMINALS, INC. v. ARTEX DEVELOPMENT CO., INC. G.R. No. L-25748 March 10, 1975 FACTS CTI was the operator of a customs bonded warehouse located at Port Area, Manila. It received on deposit of 193 bales of high density compressed raw cotton. It was understood that CTI would keep the cotton in behalf of Luzon Brokerage Corporation until the consignee thereof, Paramount Textile Mills, Inc., had opened the corresponding letter of credit in favor of shipper.

Credit Transactions - Deposit

Allegedly by virtue of a forged permit to deliver imported goods, purportedly issued by the Bureau of Customs, Artex was able to obtain delivery of the bales of cotton on after paying CTI P15,000 as storage and handling charges. At the time the merchandise was released to Artex, the letter of credit had not yet been opened and the customs duties and taxes due on the shipment had not been paid. CTI, in its original complaint, sought to recover possession of the cotton by means of a writ of replevin. The writ could not be executed. CTI then filed an amended complaint by transforming its original complaint into an action for the recovery from Artex of P99,609.76 as compensatory damages, P10,000 as nominal and exemplary damages and P20,000 as attorney's fees It should be clarified that CTI alleged that Artex acquired the cotton from Paramount Textile Mills, Inc., the consignee. Artex alleged in its motion to dismiss that it was not shown in the delivery permit that Artex was the entity that presented that document to the CTI. Artex further averred that it returned the cotton to Paramount Textile Mills, Inc. when the contract of sale between them was rescinded because the cotton did not conform to the stipulated specifications as to quality. ISSUE Whether Consolidated Terminals Inc (CTI) as warehouseman was entitled to the possession of the bales of cotton. No. CTI had no cause of action. It was not the owner of the cotton. It was not a real party of interest in the case. CTI was not sued for damages by the real party in interest. RATIO CTI in this appeal contends that, as warehouseman, it was entitled to the repossession of the bales of cotton; that Artex acted wrongfully in depriving CTI of the possession of the merchandise because Artex presented a falsified delivery permit, and that Artex should pay damages to CTI. The only statutory rule cited by CTI is section 10 of the Warehouse Receipts Law which provides that "where a warehouseman delivers the goods to one who is not in fact lawfully entitled to the possession of them, the warehouseman shall be liable as for conversion to all having a right of property or possession in the goods..." We hold that CTI's appeal has not merit. Its amended complaint does not clearly show that, as warehouseman, it has a cause of action for damages against Artex. The real parties interested in the bales of cotton were Luzon Brokerage Corporation as depositor, Paramount Textile Mills, Inc. as consignee, Adolph Hanslik Cotton as shipper and the Commissioners of Customs and Internal Revenue with

respect to the duties and taxes. These parties have not sued CTI for damages or for recovery of the bales of cotton or the corresponding taxes and duties. The case might have been different if it was alleged in the amended complaint that the depositor, consignee and shipper had required CTI to pay damages, or that the Commissioners of Customs and Internal Revenue had held CTI liable for the duties and taxes. In such a case, CTI might logically and sensibly go after Artex for having wrongfully obtained custody of the merchandise. But that eventuality has not arisen in this case. So, CTI's basic action to recover the value of the merchandise seems to be untenable. It was not the owner of the cotton. How could it be entitled to claim the value of the shipment? The negotiation of the warehouse receipt by the buyer of goods purchased from and deposited to the warehouse is valid even if the warehouseman who issued a negotiable warehouse receipt was not the buyer. The validity of the negotiation cannot be impaired by the fact that the owner/warehouseman was deprived of the possession of the same by fraud, mistake or conversion.

D. Modes of Extinguishment THE ROMAN CATHOLIC BISHOP OF JARO v. GREGORIO DE LA PEA administrator of the estate of Father Agustin de la Pea G.R. No. L-6913 November 21, 1913 FACTS This is an appeal by the defendant from a judgment of the CFI, awarding to the plaintiff the sum of P6,641, with interest at the legal rate from the beginning of the action. It is established in this case that the plaintiff is the trustee of a charitable bequest made for the construction of a leper hospital and that father Agustin de la Pea was the duly authorized representative of the plaintiff to receive the legacy. The defendant is the administrator of the estate of Father De la Pea. In the year 1898 the books Father De la Pea, as trustee, showed that he had on hand as such trustee the sum of P6,641, collected by him for the charitable purposes aforesaid. In the same year he deposited in his personal account P19,000 in the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank at Iloilo. Shortly thereafter and during the war of the revolution, Father De la Pea was arrested by the military authorities as a political prisoner, and while thus detained made an order on said bank in favor of the

Credit Transactions - Deposit

United States Army officer under whose charge he then was for the sum thus deposited in said bank. The arrest of Father De la Pea and the confiscation of the funds in the bank were the result of the claim of the military authorities that he was an insurgent and that the funds thus deposited had been collected by him for revolutionary purposes. The money was taken from the bank by the military authorities by virtue of such order, was confiscated and turned over to the Government.

that, in choosing between two means equally legal, he is culpably negligent in selecting one whereas he would not have been if he had selected the other. The court, therefore, finds and declares that the money which is the subject matter of this action was deposited by Father De la Pea in the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation of Iloilo; that said money was forcibly taken from the bank by the armed forces of the United States during the war of the insurrection; and that said Father De la Pea was not responsible for its loss.

ISSUE Whether de la Pea is liable to the petitioner for the loss of the money deposited in his personal bank account. No. RATIO In this jurisdiction, therefore, Father De la Pea's liability is determined by those portions of the Civil Code which relate to obligations. (Book 4, Title 1.) Although the Civil Code states that "a person obliged to give something is also bound to preserve it with the diligence pertaining to a good father of a family" (art. 1094), it also provides, following the principle of the Roman law, major casus est, cui humana infirmitas resistere non potest, that "no one shall be liable for events which could not be foreseen, or which having been foreseen were inevitable, with the exception of the cases expressly mentioned in the law or those in which the obligation so declares." (Art. 1105.) By placing the money in the bank and mixing it with his personal funds De la Pea did not thereby assume an obligation different from that under which he would have lain if such deposit had not been made, nor did he thereby make himself liable to repay the money at all hazards. If they had been forcibly taken from his pocket or from his house by the military forces of one of the combatants during a state of war, it is clear that under the provisions of the Civil Code he would have been exempt from responsibility. o The fact that he placed the trust fund in the bank in his personal account does not add to his responsibility. Such deposit did not make him a debtor who must respond at all hazards. There was no law prohibiting him from depositing it as he did and there was no law which changed his responsibility be reason of the deposit. While it may be true that one who is under obligation to do or give a thing is in duty bound, when he sees events approaching the results of which will be dangerous to his trust, to take all reasonable means and measures to escape or, if unavoidable, to temper the effects of those events, we do not feel constrained to hold

DISPOSITIVE: The judgment is therefore reversed, and it is decreed that the plaintiff shall take nothing by his complaint.

Credit Transactions - Deposit

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Deposits Part 1 Digest 2Dokument12 SeitenDeposits Part 1 Digest 2kmanligoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 63 BPI Vs CADokument4 Seiten63 BPI Vs CACharm Divina LascotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Dokument159 SeitenObliCon - Cases - 1240 To 1258Bianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsDokument7 SeitenSupreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsKria Celestine ManglapusNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI V CA 1994Dokument9 SeitenBPI V CA 1994Joyce KevienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsDokument10 SeitenSupreme Court: Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsBianca BeltranNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI v. CA - G.R. No. 104612Dokument5 SeitenBPI v. CA - G.R. No. 104612newin12Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private RespondentsDokument7 SeitenLeonen, Ramirez & Associates For Petitioner. Constante A. Ancheta For Private Respondentscha chaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 127739-1994-Bank of The Philippine Islands v. Court Of20181112-5466-F64ifwDokument8 Seiten127739-1994-Bank of The Philippine Islands v. Court Of20181112-5466-F64ifwShairaCamilleGarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPCL Bank DepositsDokument13 SeitenSPCL Bank DepositsJImlan Sahipa IsmaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi vs. CaDokument8 SeitenBpi vs. Cajade123_129Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of The Philippine Islands v.20210426-11-1kq1l5bDokument9 SeitenBank of The Philippine Islands v.20210426-11-1kq1l5bMaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPIDokument5 SeitenBPIHartel Buyuccan100% (1)

- 6BPI v. CA 232 SCRA 302 GR 104612 05101994 G.R. No. 104612Dokument6 Seiten6BPI v. CA 232 SCRA 302 GR 104612 05101994 G.R. No. 104612sensya na pogi langNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6BPI v. CA 232 SCRA 302 GR 104612 05101994 G.R. No. 104612Dokument6 Seiten6BPI v. CA 232 SCRA 302 GR 104612 05101994 G.R. No. 104612sensya na pogi langNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Banking DigestDokument14 SeitenCase Banking DigestmaJmaJ567% (3)

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents Pacis & Reyes Law Office Ernesto T. Zshornack, JRDokument8 SeitenPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents Pacis & Reyes Law Office Ernesto T. Zshornack, JRKizzy EspiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil 2 Deposit CasesDokument11 SeitenCivil 2 Deposit CasesbertobalicdangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deposit Cases Digests (BPI Vs IAC To Consolidated Terminals vs. Artex Development)Dokument11 SeitenDeposit Cases Digests (BPI Vs IAC To Consolidated Terminals vs. Artex Development)Ron QuintoNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI vs. IntermeDokument5 SeitenBPI vs. IntermenbragasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Title: BANK OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Petitioner, vs. THEDokument83 SeitenCase Title: BANK OF THE PHILIPPINE ISLANDS, Petitioner, vs. THEJoseph MacalintalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi vs. Iac L-66826, Aug. 19, 1988Dokument5 SeitenBpi vs. Iac L-66826, Aug. 19, 1988rosario orda-caiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of The Philippine Islands vs. Court of AppealsDokument12 SeitenBank of The Philippine Islands vs. Court of AppealsRomeo de la CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI v. CADokument5 SeitenBPI v. CAElizabeth LotillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi Vs CaDokument4 SeitenBpi Vs CaDrean TubislloNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI v. IAC, GR. No. L-66826, August 19, 1988 (164 SCRA 630)Dokument9 SeitenBPI v. IAC, GR. No. L-66826, August 19, 1988 (164 SCRA 630)Lester AgoncilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI V IACDokument14 SeitenBPI V IACRein GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Payment Digest OBLICONDokument11 SeitenPayment Digest OBLICONDumsteyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi VS Ca GR No. 104612Dokument2 SeitenBpi VS Ca GR No. 104612Bert Rosete100% (1)

- Facts:: Bpi vs. Intermediate Appellate Court 164 SCRA 630 (1988)Dokument9 SeitenFacts:: Bpi vs. Intermediate Appellate Court 164 SCRA 630 (1988)Bluebells33Noch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - Dep - BPI V IAC 164scra630Dokument13 Seiten1 - Dep - BPI V IAC 164scra630Michelle Muhrie TablizoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Law Case DigestDokument21 SeitenCommercial Law Case DigestpacburroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of The Philippine Islands vs. Iac FactsDokument2 SeitenBank of The Philippine Islands vs. Iac FactsClaudine SumalinogNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI vs. IACDokument9 SeitenBPI vs. IACJoey Ann Tutor KholipzNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30 Bank of The Philippine Islands v. Intermediate Appellate CourtDokument13 Seiten30 Bank of The Philippine Islands v. Intermediate Appellate CourtKaiiSophieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digests Mercantile LawDokument3 SeitenCase Digests Mercantile LawCheryl ChurlNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 - BPI V CADokument5 Seiten1 - BPI V CADanielle Palestroque SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- On DepositsDokument48 SeitenOn DepositsSusan Sabilala MangallenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 39 Bank of The Philippine Islands vs. Court of AppealsDokument2 Seiten39 Bank of The Philippine Islands vs. Court of AppealsJemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bank of The Philippine ISLANDS, Petitioner, vs. The Intermediate Appellate Court and Rizaldy ZshornackDokument20 SeitenBank of The Philippine ISLANDS, Petitioner, vs. The Intermediate Appellate Court and Rizaldy ZshornackJerry CaneNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI Vs CA Assigned Case DigestDokument1 SeiteBPI Vs CA Assigned Case DigestJocelyn Yemyem Mantilla Veloso100% (2)

- Banking Law CasesDokument27 SeitenBanking Law CasesAlvin JohnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest For Banking LawsDokument4 SeitenCase Digest For Banking LawsCooksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digest FinalDokument27 SeitenDigest FinalLee YouNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI V CA Cred TransDokument4 SeitenBPI V CA Cred TransPatricia Anne GonzalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents Domingo & Dizon Mauricio Law OfficeDokument11 SeitenPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents Domingo & Dizon Mauricio Law OfficeLDCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi V IacDokument7 SeitenBpi V IacGabrielAblolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allied Bank vs. Lim Sio Wan, G.R. No. 133179march 27, 2008Dokument19 SeitenAllied Bank vs. Lim Sio Wan, G.R. No. 133179march 27, 2008Aleiah Jean Libatique100% (1)

- 10 CasesDokument6 Seiten10 CasesMelfort Girme BayucanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cred Trans CasesDokument51 SeitenCred Trans CasesRoxanne DianeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3rd Set Credit Trans CasesDokument20 Seiten3rd Set Credit Trans Caseskatrinaelauria5815Noch keine Bewertungen

- Compilation of Cred Trans Cases-DacumosDokument15 SeitenCompilation of Cred Trans Cases-DacumosCandypopNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 157833 October 15, 2007 Bank of The Philippine Islands, Petitioner, GREGORIO C. ROXAS, RespondentDokument7 SeitenG.R. No. 157833 October 15, 2007 Bank of The Philippine Islands, Petitioner, GREGORIO C. ROXAS, RespondentJan Carlo Azada ChuaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Transactions (Full Text)Dokument33 SeitenCredit Transactions (Full Text)RowenaSajoniaArengaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bpi Vs Iac 164 Scra 630 1988Dokument5 SeitenBpi Vs Iac 164 Scra 630 1988ShielaMarie MalanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest: Law On Banking and FinanceDokument25 SeitenCase Digest: Law On Banking and FinanceHelen Joy Grijaldo JueleNoch keine Bewertungen

- BPI Vs CA DepositDokument1 SeiteBPI Vs CA DepositArzaga Dessa BCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deposit Case 1 BPI vs. IACDokument9 SeitenDeposit Case 1 BPI vs. IAChernandezmarichu88Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsVon EverandA Short View of the Laws Now Subsisting with Respect to the Powers of the East India Company To Borrow Money under their Seal, and to Incur Debts in the Course of their Trade, by the Purchase of Goods on Credit, and by Freighting Ships or other Mercantile TransactionsBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (1)

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionVon EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic v. Albios DigestDokument2 SeitenRepublic v. Albios Digestviva_3375% (4)

- UN - Towards Sustainable DevelopmentDokument17 SeitenUN - Towards Sustainable Developmentviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Romero v. CA DigestDokument3 SeitenRomero v. CA Digestviva_33100% (2)

- ACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.Dokument3 SeitenACE Foods, Inc. v. Micro Pacific Technologies Co., Ltd.viva_33100% (3)

- FINALS Case Digests CompilationDokument154 SeitenFINALS Case Digests Compilationviva_3388% (8)

- Coggins V New England 1986Dokument4 SeitenCoggins V New England 1986viva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- City Capital Associates VintercoDokument2 SeitenCity Capital Associates Vintercoviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Donovan v. Bierwirth - IdaDokument2 SeitenDonovan v. Bierwirth - Idaviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rosenblatt v. Getty Oil CoDokument2 SeitenRosenblatt v. Getty Oil Coviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- TSC Industries Inc. v. Northway Inc.Dokument2 SeitenTSC Industries Inc. v. Northway Inc.viva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Summary Table 2Dokument2 SeitenCredit Summary Table 2viva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Midterm Reviewer - Loan and DepositDokument12 SeitenCredit Midterm Reviewer - Loan and Depositviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- McCullough v. BergerDokument12 SeitenMcCullough v. Bergerviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- $yllabus - Special Labor LawsDokument8 Seiten$yllabus - Special Labor Lawsviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Commercial Law ReviewerDokument54 SeitenCommercial Law Reviewerviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- In Re RJR Nabisco Inc.Dokument3 SeitenIn Re RJR Nabisco Inc.viva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Conflicts of Law (Midterm)Dokument18 SeitenNotes On Conflicts of Law (Midterm)viva_330% (1)

- Venturanza v. CADokument5 SeitenVenturanza v. CAviva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"Dokument31 SeitenRules and Regulations Implementing Republic Act No. 9208, Otherwise Known As The "Anti-Trafficking in Persons Act of 2003"viva_33Noch keine Bewertungen

- Notes On Conflicts of Law (Midterm)Dokument18 SeitenNotes On Conflicts of Law (Midterm)viva_330% (1)

- Operational Business Suite Contract by SSNIT Signed in 2012Dokument16 SeitenOperational Business Suite Contract by SSNIT Signed in 2012GhanaWeb EditorialNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fashion Designing Sample Question Paper1Dokument3 SeitenFashion Designing Sample Question Paper1Aditi VermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gcse Economics 8136/1: Paper 1 - How Markets WorkDokument19 SeitenGcse Economics 8136/1: Paper 1 - How Markets WorkkaruneshnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Peace Corps Guatemala Welcome Book - June 2009Dokument42 SeitenPeace Corps Guatemala Welcome Book - June 2009Accessible Journal Media: Peace Corps DocumentsNoch keine Bewertungen

- OL2068LFDokument9 SeitenOL2068LFdieselroarmt875bNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Wrongful Termination On EmployeesDokument4 SeitenImpact of Wrongful Termination On EmployeesAvil HarshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Energy Facts PDFDokument18 SeitenEnergy Facts PDFvikas pandeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media and Information Literacy Quarter 3 Module 1Dokument67 SeitenMedia and Information Literacy Quarter 3 Module 1Joshua Catequesta100% (1)

- Zone Controller: Th-LargeDokument1 SeiteZone Controller: Th-LargeIsmat AraNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of Newly and Migrated Programs For September 2022 - WebsiteDokument21 SeitenList of Newly and Migrated Programs For September 2022 - WebsiteRMG REPAIRNoch keine Bewertungen

- UT Dallas Syllabus For cs4341.001.09s Taught by (Moldovan)Dokument4 SeitenUT Dallas Syllabus For cs4341.001.09s Taught by (Moldovan)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Baling Press: Model: LB150S Article No: L17003 Power SupplyDokument2 SeitenBaling Press: Model: LB150S Article No: L17003 Power SupplyNavaneeth PurushothamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Naval Drug Co Vs CA G R No 103200Dokument2 SeitenLa Naval Drug Co Vs CA G R No 103200UE LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- MLCP - Area State Ment - 09th Jan 2015Dokument5 SeitenMLCP - Area State Ment - 09th Jan 201551921684Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pac All CAF Subject Referral Tests 1Dokument46 SeitenPac All CAF Subject Referral Tests 1Shahid MahmudNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADAMDokument12 SeitenADAMreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nishith Desai Associates - Alternative Investment Funds - SEBI Scores Half Century On DebutDokument2 SeitenNishith Desai Associates - Alternative Investment Funds - SEBI Scores Half Century On DebutRajesh AroraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questions & Answers On CountersDokument24 SeitenQuestions & Answers On Counterskibrom atsbha100% (2)

- The 9 Best Reasons To Choose ZultysDokument13 SeitenThe 9 Best Reasons To Choose ZultysGreg EickeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Case 2 - QuestionDokument7 SeitenComprehensive Case 2 - QuestionPraveen RoshenNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Coming MailDokument4 SeitenIn Coming Mailpoetoet100% (1)

- Tesco Travel Policy BookletDokument64 SeitenTesco Travel Policy Bookletuser001hNoch keine Bewertungen

- (The Nineteenth Century Series) Grace Moore - Dickens and Empire - Discourses of Class, Race and Colonialism in The Works of Charles Dickens-Routledge (2004) PDFDokument223 Seiten(The Nineteenth Century Series) Grace Moore - Dickens and Empire - Discourses of Class, Race and Colonialism in The Works of Charles Dickens-Routledge (2004) PDFJesica LengaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal TKM B. Inggris Kls XII Des. 2013Dokument8 SeitenSoal TKM B. Inggris Kls XII Des. 2013Sinta SilviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- MF 660Dokument7 SeitenMF 660Sebastian Vasquez OsorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inkt Cables CabinetsDokument52 SeitenInkt Cables CabinetsvliegenkristofNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9a Grundfos 50Hz Catalogue-1322Dokument48 Seiten9a Grundfos 50Hz Catalogue-1322ZainalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modeling Cover Letter No ExperienceDokument7 SeitenModeling Cover Letter No Experienceimpalayhf100% (1)

- Print Design Business Model CanvasDokument3 SeitenPrint Design Business Model CanvasMusic Da LifeNoch keine Bewertungen

- User Exits in Validations SubstitutionsDokument3 SeitenUser Exits in Validations SubstitutionssandeepNoch keine Bewertungen