Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

A Review of Referrence and Implicature

Hochgeladen von

Satya PermadiCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

A Review of Referrence and Implicature

Hochgeladen von

Satya PermadiCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Introduction

Referrence and Implicature

When we use the language to talk about the world. What we say is talking about the world generally meaningful and oftentimes true. In relation with that statement, we find the terms of Reference which the relation that obtains between expression and what speaker use expression to talk about. For example; lets suppose Im in a foreign country, sitting in my hotel room at night. here is knock on the door. I dont open the door, but ask; whose there! he "isitor answers# $its me. %ow, what do I do!. In this case, there are two possibilities. &ither I recogni'e the "isitors "oice, and then I can decide whether or not to open the door. (r I dont and then Im in a )uandary. What can I do with a "oice that refers to a *me+, when I dont know who that $me is! ,ince a $me always refers to an $I, and e"ery $I is a speaking $me, the utterance $its me, is always and necessary true, and hence totally uninformati"e, when it comes to establishing a speakers identity. -lthough it )uestionable whether all word refer, there are se"eral types of word which are arguably of the referring sort. he central )uestions concerning reference is# how do word refer! ,ubsidiary )uestions concern the relation between reference and meaning and reference and truth will be briefly discussed in this re"iew. ,o, Reference is important because it is thought to be the core of meaning and content.

Summary

The Philosophy of Reference %owadays, we use language to refer to persons and things, directly or indirectly. In the first case .direct reference/, we ha"e name a"ailable that we lead us to persons and things. 0ut, in second case .indirect reference/, we need to ha"e resource to other, linguistics as well as non linguistic, strategies in order to establish the correct reference. -s the 1erman psychologist2 philosopher of language , 3arl 0uhler expressed it more than fifty years ago, &"erybody can say I, and whoe"er says it, points to another ob4ect than e"erybody else; one needs as many proper names as there are speakers, in order to map .in the same way as in the case of the nouns/ the intersub4ucti"e ambiguity of this one word into the ambiguous reference of linguistic symbols. .5678# 597# :eys translation/ -ccording to 0uhler .and in the spirit of the period/, such an $unambiguous reference is demanded of language by the logicians. In the same spirit, some of the letter in all sincerity proposed that we should abolish words with $unclear reference such as $I or $;ou, because there is no way of checking whether they correspond to something $out there; as their reference is always shifting.

Reference and indexical expressions raditionally, the proper nouns .from latin nomen proprium, a name that belongs to somebody or something/ are the prime example of linguistic expressions with $proper reference; names name person, institutions and in general, ob4ects whose reference is clear. Indexical expressions are a particular kind of referential expressions, where the reference is not 4ust $badly semantic, but includes a reference to the particular context in which the semantics is put to work. For example# I am six feet tall.

he meaning of $six feet tall is gi"en by what the indi"idual words mean, and any competent user of &nglish will understand them as indicating a certain height of the person uttering the words. he problem is in the $I particular speaker! hat can only be decided by looking at the context in which the words are uttered.

Pragmatic function of indexicals When we talk about the linguistic means of expressing an indexical relationship, we usually refer to the so2called deitic elements of the language. -s we ha"e seen the function of such $indexing expressions .we can think of them as $pointers/ is to tell us where to look for a reference. -ll indexical expressions refer to certain world conditions, either sub4ucti"e or ob4ecti"e in nature. <onsider the case of $time. If I say #I saw him last week, my $point of time, that is, $last week, depends on the point of time Im at now; that is, the time of my uttering $I saw him last week for any old week, the week that is my point of time. I cannot used $last week for any old week that has come before some other week; it has to be the week that is $last from my current point of "iew. For a week that process .an/ other week.s/, in general, we used the proceding week or the week before.

Discourse Deixis Referring to context is important in the pragmatic area. 0ut some referent may cannot be identified through their proper context and the speaker may using some expression. For example the use of pronoun $this, *I need a box this big+ this sentence is ambiguous if we 4ust see or hear it. herefore, the referent need to illustrate what is the sentences talking about with mo"ing hands and arms to indicate exactly how big the box should be. ,o, the hearer can understand the speakers meaning precisely, this can be called as deictic expressions. he other example is *I met this girl the other day+ In this case $ his is referred to a girl which ha"e little interest from the speaker, and it can be called as reminder deixis. From the example abo"e, a deitic elements often indicates other things than the original ,patial deixis .here, there/ and .now, then/ emporal deixis

Deixis to Anaphor In relation to deictic, there are also anaphora, in which both of this pointing feature ha"ing almost same feature. =eictic is using expressions .gestural or symboli'ing/ to refer something or it can be said indexical reference, meanwhile anaphora reference to something already introduced in the text or in other words it in"ol"es resuming>repetition. -ccording to ?e"inson .56@7/, anaphora concerns with the use of a pronoun to refer to the same referent as some prior term. For example in the pronominal referents, * The man was walking softly, he carried a big stick.+ -s we can see, the words $the man it has been spoken of earlier and known as referent. :oreo"er the word $he refers anaphorically to $the man. In addition, when the referent comes before the pronoun it can be called cataphora. *Aes been to Italy many times but he still doesnt speak the language+ In the words $the language does not refer to any language that has been mentioned pre"iously, howe"er we understand it immediately as $the language of Italy, since Italy has been mentioned. 0oth are different in their function but can be same in utterance of a single morpholexical item, for example, *I was born in London and ha"e li"ed there e"er since+ where the place ad"erb is anaphoric because it refers to the same entity as ?ondon, but it is also deictic because it contrasts with here on the deictic dimension of space, and locates the utterance outside ?ondon. In conclusion, it can be defined define deixis as indexical reference and anaphora as resuming>repetition. 0oth ha"e two definitions, based on different criteria, identify two functions that do not exclude each other.

Implicature Implicature means to imply :ey .5667/. In daily con"ersation, what a speaker says is not always, what the speaker implies. When the meaning of an utterance is implied, so we need to in"ol"e the context where the utterance is uttered. herefore, implicature can be defined as the implied meaning by in"ol"ing the context.

Implication and Implicature :ey .5667/ distinguishes between implication and implicature. Implication according to :ay .5667/ refers to logical relationship between two propositions. he two proposition is that if $p then $). or p ).

e.g. a father says to his son Take me to airport .symboli'ed as p/ I will buy a new car for you .symboli'ed as )/ hen logical expression between p B ) is that, p father will buy a new car for his son. If for example, the father refuses to buy a new car for his son after the son brought his father to airport, the son will claim. he sons claim here is not only rightful but also logical because if $p then $). Aowe"er, if the son does not bring his father to airport .non2p/, then the father also does not buy a new car for his son .non2)/. If it happens, there is no claim between the two. (n the other hand, the father continues to buy a new car for his son, then, there will be no claim as well. It means that non2p does not imply non2). In this case, logical implication in e"eryday life is not always true. herefore, we need another term con"ersational implicature. Furthermore. 1rice di"ides implicature into con"ersational and con"ensional implic ) so if the son brings her father to airport, the

Conversational Implicatures Interpreting what a speaker says sometimes leads to misleading or misunderstanding. ?eech .56@7/ in Cacob mentions that interpreting the utterance of speakers is a kind of guesswork. ?eech then proposes the example $)uestion# when is aunt Roses birthday! -nswer# its sometimes in April. he answer gi"en seems to be "ery unclear because sometimes is not to say specifically; it then may refers to early, middle, or end of -pril or in between 5 st and 79th of -pril. Its possible to say sometimes e"en the actual date is 5st of -pril for example. when the

speaker knows the date but he>she says sometimes, it maybe strike the listener as somewhat bi'arre. ,uch example, of expression sometimes in April refers to conversational implicature instead of logical and semantic criteria in which it is the only information that is remembered by the speaker because he>she honestly does not know exactly the date of -unt Roses birthday. In daily con"ersation, the guess like the gi"en example can be said as )ualified but it is based on the context. he more we know about the context, the more well2grounded or guesswork is going to be. he answer such sometimes in April actually is not a fact based on logical and semantic meaning. 0elow is the example gi"en from ?eech .567@#@D/ in :ey. he expression of a fact that the child eats some of the raisins by uttering Alexandra ate some of the raisin his utterance has limited in scope in term of the fact that she eats some not all, thus if the utterance is to say $but why did you have to eat all those raisins? When the second sentence is uttered, she will refuse it because she logically and con"ersationally ate $some and not $all. In different situation, for example some turns out to be all when the fact is he ate all the biscuits then we say Alex ate some of the biscuits, In fact, she ate all of them In this situation, the sum of total e"eryday language use hold the meaning of what we say. hus we can decides that whether the meaning of all and some is a logical or pragmatic one. Conventional Implicatures Implicature is e"erything that is not co"ered by the truth conditional logic .:ey, 5667/. For example, when we say about the word last, it can be meant by the ultimate item in se)uence e.g. the last of manuscript a conventional implicature , but it can also be meant by something that

come before the following thing, e.g. the last winter a conversational implicature . It can be inferred that con"ersational implicature is the meaning that is implied by the context while con"entional implicature is the meaning implied directly.

A Detailed Evaluation of the Chapter

hus far, this study has been concerned largely with what might be called indexical expression and indexical function of reference. Reference, construed as a relation between bits of language and bits of reality, is assumed to be a genuine, substanti"e relation worthy of philosophical scrutiny. -ccounts .whether descripti"e, causal, or hybrid/ are then gi"en of what constitutes this link. :oreo"er, some philosophers .as 4ust noted/ belie"e that referential theories ha"e important implications for metaphysical and epistemological issues. 0ut not all philosophers are so sanguine about the possibility or theoretical importance of reference. he weakness is find on some $negati"e "iews of reference. Euine .56F9/ has argued that reference is inherently indeterminate or $inscrutable. 0y this, Euine means that there is no fact of the matter as to what our words refer to. It is not that our words refer to something but we are unable to determine what that is. Rather, there is no such thing as what our words refer to. %e"ertheless, Euine does not go so far as to say that our words fail to refer in any sense. Ais "iew is rather that it makes sense to speak of what our words refer to only relati"e to some purpose we might ha"e in assigning referents to those words. =a"idsonGs instrumentalist "iews on reference are e"en more radical than EuineGs. =a"idson .56@8/ claims that reference is a theoretically "acuous notion# it is of absolutely no use in a semantic theory. Ais basis for endorsing this position is his con"iction that no substantive explanation of reference is e"en possible. he problem is that any such explanation would ha"e to be gi"en in non lin!uistic terms H but no such explanation can be gi"en. -s he puts it .56@8, p. II9/# If the name $3iliman4aro refers to 3iliman4aro, then no doubt there is some relation between &nglish .or ,wahili/ speakers, the word, and the mountain. 0ut it is inconcei"able that one should be able to explain this relation without first explaining the role of the words in the sentences; and if this is so, there is no chance of explaining reference directly in non2linguistic terms. Aowe"er, this does not mean that there is no hope for semantics. (n the contrary. (n =a"idsonGs "iew, a arskian theory of truth for a language is at the same time a theory of

meaning for that language. he point here is that a =a"idsonian theory of meaning has no place for the notion of reference. ,imilar in spirit to =a"idsonGs "iews are the "iews of the deflationists. ,uch theorists claim that there is nothing more to referential notions than is captured by instances of a schema like $a refers to a. ,uch a schema generates claims like $"re!erefers to "re!e. ,uch "iews are often accompanied by, and moti"ated by, a deflationary theory of truth, according to which to assert that a statement is true is 4ust to assert the statement itself. =espite these $negati"e "iews of reference, the nature of the relation between language and reality continues to be one of the most talked about and "igorously debated issues in the philosophy of language. Overvie of Deixis -ccording to ;ule .566F/, deixis means *pointing language+. -ny linguistic form used to accomplish this GpointingG is called a deictic expression. When you notice a strange ob4ect and ask, GWhatGs that! you are using a deictic expression .GthatG/ to indicate something in the immediate context. =eictic expressions are also sometimes called indexicals. hey are among the first forms to be spoken by "ery young children and can be used to indicate people "ia person deixis .GmeG, GyouG/, or location "ia spatial deixis .GhereG, GthereG/, or time "ia temporal deixis .GnowG, GthenG/, or expression used to refer to earlier "ia discourse deixis .$this, $that, $there/ and to show respect "ia social deixis .$you, $your/ .?e"inson, 56@7 in Aorn ?. R. B Ward 1. I998/. -ll these expressions depend, for their interpretation, on the speaker and hearer sharing the same context. he important things that we need to focus is how discourse deixis can be related to anaphora. 0ut, before go further, it is good to know fields of deixis first.

!ields of Deixis 5. Jerson =eixis

-ccording to ;ule .566F/, person deixis clearly operates on a basic three2part di"ision, exemplified by the pronouns for first person .GIG/, second person .GyouG/, and third person .GheG, GsheG, or GitG/, for example; 3oko says, *I missed the train+ the word I refers to 3oko.

I. ,patial =eixis ,patial deixis specifies the location relati"e to the speaker and the addressee .;ule, 566F/. 0asically it uses two ad"erbs, GhereG and GthereG, moreo"er there are also in"ol"es "erbs of motion, GcomeG and GgoG, it retain deictic sense when they are used to mark mo"ement toward the speaker .*<ome to bed+/ or away the speaker .*1o to bed+/. ,peakers also seem to be able to pro4ect themsel"es into other locations prior to actually being in those locations, for example; *IGll come later+ .mo"ement to addresseeGs location/

7.

emporal =eixis -ccording to ;ule .566F/, temporal deixis locates points or inter"als on the time axis, using the moment of utterance as a reference point. 0asically it refers to words and phrases like now, then, today, yesterday, tomorrow, next week, last year, in three days, etc. 0ut imagine if we donGt know the utterance reference point, for example; there is a note on office door *0ack in an hour+ In this case, we donGt know if we ha"e a short or a long wait ahead.

8. ,ocial =eixis ?e"inson, .56@7/ in Aorn ?. R. B Ward 1. .I998/ state that social deixis concerns social relationship between participants, their status, and relation to the topic of the discourse. he honorific form is used to show respect *1ood e"ening, :r. Jresident+. In many languages these deictic categories of speaker, addressee, and other.s/ are elaborated with markers of relati"e social status .for example# from the French forms GtuG .lower, younger, less powerfull/ and G"ousG .higher, more powerfull/.

D. =iscourse =eixis =iscourse deixis is an expression that has its reference within the discourse or text .?e"inson, 56@7 in Aorn ?. R. B Ward 1. I998/. For example, in the pre"ious section, in the next chapter, in the rest of this paper, in conclusion, etc. .usually used in texts/ and this, that, there, next, last .usually used in utterances/. In addition, :ey .5667/ state that there also a case where the referent cannot be identified in spoken or written text. When using pronoun $this, *I need a box this big+ this sentence is ambiguous if we 4ust see or hear it. herefore, the referent need to illustrate what is the sentences talking about with mo"ing hands and arms to indicate exactly how big the box should be. ,o, the hearer can understand the speakers meaning precisely. he fi"e types of deixis are used to identify something in the current physical context or within the discourse or text. In discourse or text, deixis is used to keep track of who or what is being talked about more than once. -fter the initial introduction of some entity the speaker>writer will use deixis to maintain reference with replacing the initial introduction .antecedent/. his function can be called as anaphora .:ey, 5667/. For example; * he man was walking softly, he carried a big stick.+ -s we can see, the words $the man it has been spoken of earlier and known as referent. :oreo"er the word $he refers anaphorically to $the man .it replace antecedent/. In addition, according to :ey .5667/ the re"ersal of the antecedent2anaphor pattern is known as cataphora, which is less common. For example; *I could hardly belie"e it. he man wriggled his pointing finger through the brick+ In which, the reference of it located in the next sentence.

Discussions and Argued Points

Reference is arguably the central notion in the philosophy of language, with close ties to the notions of meaning and truth. 0ut one might wonder whether reference has implications for philosophical issues that go beyond the philosophy of language proper. :any ha"e thought that it does, and many of these philosophers ha"e seen connections between reference and reality H the nature of which is the sub4ect matter of metaphysics. (ne of the oldest metaphysical problems H the so2called $problem of non2being H in"ol"es the notion of reference. :any others ha"e seen connections between reference and knowled!e H the nature of which is the sub4ect matter of epistemolo!y# (ne of the newest epistemological problems H presented "ia JutnamGs infamous $brain in a "at thought2experiment H also in"ol"es the notion of reference. In contrast, there are philosophers who belie"e that reference H construed as pro"iding a substanti"e link between language and the world H is not a sub4ect worthy of serious philosophical study. Karious reasons ha"e been gi"en for this negati"e attitude toward reference, including# .i/ reference is inherently indeterminate .Euine, 56F9/, .ii/ the notion of reference is without theoretical "alue .=a"idson, 56@8/, and .iii/ all that one can say about reference is what is embodied by instantiations of a schema like LaM refers to a. :eanwhile in another argued point that can be propose is the anaphoric feature. -s we can see abo"e, we can use anaphor function that used to maintain reference with replacing the

initial introduction .antecedent/ by using some pronouns, for example; this, they, he, she, it. Aowe"er, not all languages ha"e this feature .:ey, 5667/. For instance, in ,panish, in situation where there are both male and female teacher present. If want to referring them, we should use los profesores .for the male teacher/ and las profesoras .for the female teacher/. It can be said that, there is a gender distinction between male and female .los>las profesores>as/. In addition, to express the pronoun $she in ,panish .la or ending with 2a/, it sometimes conflicts with the male noun. For example; la catdratico .the female professor in uni"ersity/ the article la .female gender/ it should be with the end with $a in the noun .like the example in the paragraph abo"e las profesoras/ but in the pre"ious example the use of la conflicts with the male gender .catdratico/ and it "iolates the ,panish grammar. his case can be called as syntactic clash. he grammarian might will us to a"oid this syntactic clash, but in Jragmatics "iew, this clashes is interesting that happened in social group, especially how these clashes are expressed.

Conclusion

raditionally, the proper nouns .from latin nomen proprium, a name that belongs to somebody or something/ are the prime example of linguistic expressions with $proper reference; names name person, institutions and in general, ob4ects whose reference is clear. Indexical expressions are a particular kind of referential expressions, where the reference is not 4ust $badly semantic, but includes a reference to the particular context in which the semantics is put to work. In general, deixis means *pointing language+. o indicate something in the immediate

context we might using $that. In conclusion, it can be defined define deixis as indexical reference and anaphora as resuming>repetition. 0oth ha"e two definitions, based on different criteria, identify two functions that do not exclude each other. If we want to indicate people we can use person deixis .GmeG, GyouG/, or indicate location "ia spatial deixis .GhereG, GthereG/, or indicate time "ia temporal deixis .GnowG, GthenG/, or indicate expression used to refer to earlier "ia discourse deixis .$this, $that, $there/ and to show respect "ia social deixis .$you, $your/. he fi"e types of deixis are used to identify something in the current physical context or within the discourse or text. In discourse or text, deixis is used to keep track of who or what is being talked about more than once. -fter the initial introduction of some entity the speaker>writer will use deixis to maintain reference with replacing the initial introduction .antecedent/. his function can be called as anaphora.

RE!ERE"CES

=a"idson, =. .56@8/, In%uiries into Truth and Interpretation, (xford# <larendon Jress. Aorn ?. R. B Ward 1. .I998/. The &andbook of 'ra!matics. Retrie"ed Canuary 58, I957, from, http#>>www.stiba2malang.ac.id>uploadbank>pustaka>:3?I%1NI, I3>A-%=0((3 OI9(FOI9JR-1:- I<,OI9A(R%.pdf :ey ?. C. .5667/, 'ra!matics An Introduction, (xford# 0lackwell Euine, W.K.(. .56F9/, (ord and )b*ect, <ambridge :-# :I Jress. Euine, W.K.(. .56F5/, "rom a Lo!ical 'oint of +iew, <ambridge :-# :I Jress. ;ule, 1. .566F/. 'ra!matics. (xford# (xford Nni"ersity Jress.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Interview Q SASDokument43 SeitenInterview Q SAShimaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hotel and Resort English English Lesson Plans For The Hospit PDFDokument151 SeitenHotel and Resort English English Lesson Plans For The Hospit PDFTeresa Barón García100% (1)

- Characteristic of Human LanguageDokument1 SeiteCharacteristic of Human LanguageSatya Permadi50% (2)

- Strike RiskDokument4 SeitenStrike RiskAdilson Leite ProençaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 0 Tdi SSPDokument90 Seiten2 0 Tdi SSPmicol53100% (1)

- Instructure List in A CollegeDokument2 SeitenInstructure List in A CollegeSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ability BingoDokument1 SeiteAbility BingoFlor HenríquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching Schedule in A CollegeDokument3 SeitenTeaching Schedule in A CollegeSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Instructure List in A CollegeDokument2 SeitenInstructure List in A CollegeSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture ContractDokument3 SeitenLecture ContractSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kelompok Bahasa InggrisDokument65 SeitenKelompok Bahasa InggrisSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scientific Approach ObservingDokument2 SeitenScientific Approach ObservingSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Nature of Lesson Plan and Example - CoverDokument1 SeiteThe Nature of Lesson Plan and Example - CoverSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- PragmatismDokument7 SeitenPragmatismSatya Permadi100% (1)

- English Middle Test - Score Refinement (Student Version) (LCKD)Dokument2 SeitenEnglish Middle Test - Score Refinement (Student Version) (LCKD)Satya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Components of Lesson Plan Based On 2013 CurriculumDokument2 SeitenComponents of Lesson Plan Based On 2013 CurriculumSatya Permadi100% (1)

- Literature 1 Poetry: Komang Satya Permadi 0912021061 4CDokument1 SeiteLiterature 1 Poetry: Komang Satya Permadi 0912021061 4CSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morphology (Suffix, Prefix, Affix)Dokument5 SeitenMorphology (Suffix, Prefix, Affix)Satya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fulbright Dikti Master Degree ScholarshipDokument2 SeitenFulbright Dikti Master Degree ScholarshipSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discourse Analysis - Mood & Transitivity AnalysisDokument12 SeitenDiscourse Analysis - Mood & Transitivity AnalysisSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angel Falls: Angel Falls (Spanish: Salto Ángel Pemon Language: Kerepakupai Vena, MeaningDokument1 SeiteAngel Falls: Angel Falls (Spanish: Salto Ángel Pemon Language: Kerepakupai Vena, MeaningSatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammar Translation Method and Direct MethodDokument9 SeitenGrammar Translation Method and Direct MethodSatya Permadi100% (1)

- A Critical Perspective - Language Hegemony, Linguistic Inequality, and Cultural Disempowerment in Educational Setting by Komang Satya PermadiDokument5 SeitenA Critical Perspective - Language Hegemony, Linguistic Inequality, and Cultural Disempowerment in Educational Setting by Komang Satya PermadiSatya Permadi0% (1)

- Cross-Linguistic Influence and Learner LanguageDokument11 SeitenCross-Linguistic Influence and Learner LanguageSatya Permadi50% (2)

- 2015 Fulbright FLTADokument3 Seiten2015 Fulbright FLTASatya PermadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Seminar On ELT: Visual MediaDokument15 SeitenSeminar On ELT: Visual MediaSatya Permadi100% (1)

- Ecolinguistics by Komang Satya PermadiDokument7 SeitenEcolinguistics by Komang Satya PermadiSatya Permadi100% (1)

- The Term Semantics and MeaningDokument18 SeitenThe Term Semantics and MeaningSatya Permadi100% (1)

- Research Methodology PDFDokument338 SeitenResearch Methodology PDFBruno H Linhares PNoch keine Bewertungen

- KW Kwh/YrDokument3 SeitenKW Kwh/YrHaris BaigNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is A Determiner?Dokument15 SeitenWhat Is A Determiner?Brito Raj100% (4)

- Design, Development, Fabrication and Testing of Small Vertical Axis Wind TurbinevDokument4 SeitenDesign, Development, Fabrication and Testing of Small Vertical Axis Wind TurbinevEditor IJTSRDNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Build An Offshore CraneDokument5 SeitenHow To Build An Offshore CraneWestMarineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Directional & Horizontal DrillingDokument23 SeitenDirectional & Horizontal DrillingMuhammad shahbazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Data StructuresDokument2 SeitenData StructuresRavi PalNoch keine Bewertungen

- B.S. in Electronics Engineering - BSECE 2008 - 2009Dokument2 SeitenB.S. in Electronics Engineering - BSECE 2008 - 2009Vallar RussNoch keine Bewertungen

- Weather ForecastsDokument5 SeitenWeather ForecastsGianina MihăicăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tafl KCS 402 Cia-I 2019-20Dokument2 SeitenTafl KCS 402 Cia-I 2019-20vikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Java Programming For BSC It 4th Sem Kuvempu UniversityDokument52 SeitenJava Programming For BSC It 4th Sem Kuvempu UniversityUsha Shaw100% (1)

- Danas Si Moja I BozijaDokument1 SeiteDanas Si Moja I BozijaMoj DikoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maf 5102: Financial Management CAT 1 20 Marks Instructions Attempt All Questions Question OneDokument6 SeitenMaf 5102: Financial Management CAT 1 20 Marks Instructions Attempt All Questions Question OneMuya KihumbaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Data (No Longer Current But Cited in The Building Regulations)Dokument290 SeitenDesign Data (No Longer Current But Cited in The Building Regulations)ferdinand bataraNoch keine Bewertungen

- TIMSS Booklet 1Dokument11 SeitenTIMSS Booklet 1Hrid 2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fork LiftDokument4 SeitenFork Lifttamer goudaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fuzzy Hungarian Method For Solving Intuitionistic FuzzyDokument7 SeitenFuzzy Hungarian Method For Solving Intuitionistic Fuzzybima sentosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Maths Project: Made By:-Shubham Class: - Viii-CDokument25 SeitenMaths Project: Made By:-Shubham Class: - Viii-CsivaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tautology and ContradictionDokument10 SeitenTautology and ContradictionChristine Tan0% (1)

- Paragon Error Code InformationDokument19 SeitenParagon Error Code InformationnenulelelemaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CELLSDokument21 SeitenCELLSPhia LhiceraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project, Program and Portfolio SelectionDokument40 SeitenProject, Program and Portfolio Selectionsaif ur rehman shahid hussain (aviator)Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spicer Info - AXSM-8663 PDFDokument28 SeitenSpicer Info - AXSM-8663 PDFRay Ayala100% (1)

- ACUCOBOL-GT Users Guide v8 Tcm21-18390Dokument587 SeitenACUCOBOL-GT Users Guide v8 Tcm21-18390Miquel CerezuelaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Process Control Plan Excel TemplateDokument13 SeitenProcess Control Plan Excel TemplateTalal NajeebNoch keine Bewertungen

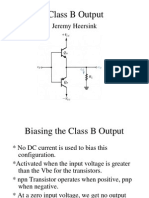

- Class B Output: Jeremy HeersinkDokument10 SeitenClass B Output: Jeremy Heersinkdummy1957jNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPMC Unit 2Dokument31 SeitenMPMC Unit 2nikitaNoch keine Bewertungen