Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Applications of Telecounselling in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review With Effect Sizes

Hochgeladen von

justin_saneOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Applications of Telecounselling in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation: A Systematic Review With Effect Sizes

Hochgeladen von

justin_saneCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Clinical Rehabilitation

27(12) 1072 1083

The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0269215513488001

cre.sagepub.com

CLINICAL

REHABILITATION

Introduction

Telecounselling the application of individual or

group-based counselling services using telecommuni-

cation technology, such as the telephone, video tele-

phone, videoconferencing, email correspondence, or

audio-video transmission via the internet

1

has the

potential to extend mental healthcare to community-

dwelling adults with spinal cord injuries. Specifically,

telecounselling offers the possibility of an equitable,

affordable and accessible mental health service to pro-

vide consultation, monitoring and treatment.

2,3

To date, however, research examining the

potential use of telecounselling in spinal rehabili-

tation has been limited in both quantity and

488001CRE271210.1177/0269215513488001Clinical RehabilitationDorstyn et al.

2013

School of Psychology, University of Adelaide, South Australia

Corresponding author:

D Dorstyn, School of Psychology, University of Adelaide,

North Terrace Campus, Adelaide, South Australia 5000,

Australia.

Email: diana.dorstyn@adelaide.edu.au

Applications of telecounselling

in spinal cord injury

rehabilitation: a systematic

review with effect sizes

Diana Dorstyn, Jane Mathias and Linley Denson

Abstract

Objective: To investigate the short- and medium-term efficacy of counselling services provided remotely

by telephone, video or internet, in managing mental health outcomes following spinal cord injury.

Data sources: A search of electronic databases, critical reviews and published meta-analyses was

conducted.

Review methods: Seven independent studies (N = 272 participants) met the inclusion criteria.

The majority of these studies utilized telephone-based counselling, with limited research examining

psychological interventions delivered by videoconferencing (N

study

= 1) or online (N

study

= 1).

Results: There is some evidence that telecounselling can significantly improve an individuals management

of common comorbidities following spinal cord injury, including pain and sleep difficulties (d = 0.45).

Medium-term treatment effects were difficult to evaluate, with very few studies providing these data,

although participants have reported gains in quality of life 12 months after treatment (d = 0.88). The main

clinical advantages are time efficiency and consumer satisfaction.

Conclusion: The results highlight the need for further evidence, particularly randomized controlled

trials, to establish the benefits and clinical viability of telecounselling.

Keywords

Spinal cord injuries, telecounselling, telerehabilitation, treatment outcome, systematic review

Received: 23 November 2012; accepted: 7 April 2013

Article

Dorstyn et al. 1073

quality. First, most telecounselling research has

examined other physical disabilities (e.g. stroke,

multiple sclerosis),

4

making it difficult to extrap-

olate the findings to spinal cord injury. Second,

these heterogeneous samples often include indi-

viduals with comorbid cognitive problems (e.g.

stroke, traumatic brain injury), who require dif-

ferent psychological assessments and interven-

tions.

5

Third, trials that have evaluated the

application of telecommunication technology

within spinal rehabilitation have incorporated

diverse treatment programmes, including tele-

medicine, telenursing and multidisciplinary

telerehabilitation, making it difficult to isolate

the effectiveness of counselling-only services.

6

Finally, there are very few qualitative or quantita-

tive reviews specific to this area.

4

Faced with

limited available research, we recently attempted

to address some of these problems by conducting

a meta-analysis of telecounselling research

involving people with chronic physical condi-

tions that have a significant disease burden,

7

namely spinal cord injury, limb amputation,

severe burn injury, stroke and multiple sclerosis.

4

While informative, this analysis was limited to

telephone-based counselling services only, was

not specific to the spinal cord injury population

and, moreover, pre-dated a number of recent tele-

counselling trials that can now be used to narrow

the focus of our analysis to this group.

The current study was therefore designed to con-

solidate the available evidence on the efficacy of

telecounselling in spinal rehabilitation by undertak-

ing a systematic review of this research. The specific

goals were to evaluate the clinical characteristics of

telephone-, video- and internet-based counselling

programmes, namely the: (1) treatment delivery

characteristics (e.g. duration, frequency); (2) short-

term treatment effects (defined as improvements

made from baseline to the period immediately after

telecounselling ceased), and medium-term effects

(defined as any maintenance effects observed after

telecounselling had ceased); and (3) process out-

comes (e.g. attrition rates and cost analyses, where

available). Given the very limited research in this

area, the magnitude of treatment change associated

with telecounselling could not be predicted.

Method

Eligible studies were sourced from six electronic

databases: PubMed, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Scopus,

Cochrane Library, Web of Science (see Appendix for

keywords). The search was restricted to full-text arti-

cles published in English in peer-reviewed journals

between January 1970 (empirical studies of telephone

counselling services dated from that year

8

) and

January 2013. Meta-analytic and systematic reviews

of the telerehabilitation and disability literature,

4,6,911

were also reviewed for additional published empirical

studies, as were the bibliographies of all retrieved

studies and the Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation

Evidence database (www.scireproject.com).

Eligible studies had to: (1) target an adult sample

with an acquired spinal cord injury (18 years); and

(2) conduct a telecounselling intervention that

involved healthcare professionals (nurses, social

workers or psychologists) directly interacting with

clients to facilitate psychological recovery follow-

ing injury.

1,4

This included the use of online inter-

ventions where real-time access to a clinician (e.g.

via telephone) was available.

1

Interventions also

had to (3) assess treatment efficacy using one or

more standardized measures of psychological out-

come (e.g. anxiety, depression, quality of life).

Given the very limited research in this area, quasi-

experimental designs that either used a standard-

care control group or no control condition (which is

often necessary in clinical settings),

12,13

were

included in this review.

Studies were excluded if: (1) the sample compo-

sition was heterogeneous and included participants

with a spinal cord injury in addition to those with

another chronic illness or disability (e.g. stroke,

multiple sclerosis), and where the data for spinal

cord injury patients could not be separately extracted;

(2) the telecounselling intervention focused on fam-

ily caregivers and not individuals with a spinal cord

injury; (3) the primary focus of the intervention was

not psychosocial (i.e. only entailed medical, nursing

or physical therapies); (4) the study had a multidisci-

plinary focus and did not specifically evaluate the

counselling component; or (5) treatment efficacy

was only assessed using non-standardized clinical

interviews (N.B. standardized interviews, such as

1074 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(12)

the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression

Scale,

14

were eligible for inclusion).

Data extraction and analysis

The quality of each study meeting inclusion criteria

was evaluated using the Oxford Centre for Evidence

Based Medicine guidelines.

15,16

Accordingly, studies

with greater methodological rigor (e.g. randomized

clinical trials) received a higher rating (level 1 or 2,

depending on the number of participants and statisti-

cal power), meriting a higher grade of recommenda-

tion (grades A or B, respectively). In comparison,

studies received lower ratings (i.e. level 3), and a

lower grade of evidence (C), if they were non-ran-

domized or did not include a control or comparison

group (level 4 or 5). Methodological evaluation

involved consensus ratings by the first and second

authors (DD, JM).

For ease of data collection and interpretation, and

in accordance with the Cochrane Collaboration

17

and PRISMA

18

statements for reporting of system-

atic reviews, a data extraction sheet was used to

summarize key information from each study,

namely: sample demographics (e.g. sample size,

age, gender, race), methodological variables (e.g.

sample size, sampling method, control condition),

and characteristics of the implemented telecounsel-

ling programmes (e.g. programme aims, session fre-

quency and duration). Data extraction was completed

by the first author (DD).

Effect size estimation. To determine telecounselling

treatment effects, Cohens d effect sizes

19

were calcu-

lated for every outcome measure used by a study. Both

the short-term treatment effects (change in outcome

measures from pre- to post-telecounselling) and the

maintenance of treatment gains (post-telecounselling

to follow-up) were evaluated. Different Cohens d for-

mulae

20

were needed for studies that did and did not

use control groups. The direction of each effect size

was standardized across measures so that a positive

effect indicated that telecounselling was beneficial. A

negative d indicated either a worsening of symptoms

among the telecounselling participants, or signifi-

cantly more improvement in controls.

21

Cohens

d-values of 0.2, 0.5 and 0.8 equate to small, medium

and large treatment effects, respectively,

19

with statisti-

cally significant treatment effects having 95% confi-

dence intervals that do not span zero.

21

The original aim was to perform a meta-analysis

in which the data from multiple studies would be

averaged, however there was insufficient overlap in

the communication technologies (telephone, video

and internet); study designs (randomized controlled

trials vs. quasi-experimental); samples (i.e. inpatient

vs. outpatient); and treatment characteristics (e.g.

assessment intervals, outcome measures) of the

studies deemed eligible for inclusion.

21

Consequently,

the effect sizes from these studies were unsuitable to

pool.

22

Importantly, however, the calculation of

effect sizes for individual studies still provided a

standardized metric by which to compare the magni-

tude of treatment effects from different studies,

thereby providing a valuable contribution to the lit-

erature. Moreover, effect sizes provide the best

method by which to assess clinical, as opposed to

statistical, significance because unlike statistical

tests of significance they are not influenced by sam-

ple size.

21

Results

Participant characteristics

Seven independent clinical studies met all inclusion

criteria

2329

(Figure 1) and in combination they

comprised 272 participants with spinal cord injury

some (n = 52)

23,25

of whom commenced telecoun-

selling during their inpatient rehabilitation, and the

remainder (n = 220)

24,2629

in the community.

Injuries were acquired either recently or in the pre-

ceding 832 years (mean = 20.4; SD = 16.89 years).

The average age of participants was 41 years (SD =

12.2) and most were male (78%, n = 211). Five

studies recruited culturally and linguistically diverse

groups

23,25,26,28,29

(Caucasian: n = 184; 68%;

African-American: n = 75; 28%; Hispanic: n = 12;

4%). One study

29

examined the delivery of a tele-

counselling intervention that was jointly delivered

to individuals (n = 57) and family members (n =

57); however, consistent with the inclusion criteria

for this review, only the data for injured individuals

were considered here.

Dorstyn et al. 1075

Study evaluation

No study had the methodological rigor required for

the highest level of evidence (level 1). Two ran-

domly allocated participants to treatment and con-

trol conditions and were rated level 2.

28,29

Dorstyn

and colleagues

24

also used a randomized design,

but due to low statistical power this study was rated

at level 3. The remaining four studies

23,2527

were

assigned level 4 ratings due to non-randomized

treatment allocation or failure to use a control

group. Importantly, six of the seven studies

2328

were described as preliminary or pilot trials,

designed to evaluate the clinical feasibility of tele-

counselling and inform the power estimates of

subsequent research. The mean sample size was 27

participants per treatment (telecounselling) arm

(SD = 16.84) and 39 participants per control condi-

tion (SD = 20.5), although sample size varied con-

siderably across the seven studies (range: 3104).

Control conditions (N

studies

= 3)

24,28,29

included

standard outpatient care, which involved access to

multidisciplinary care (e.g. medicine, nursing, phys-

iotherapy) when needed (N

studies

= 2; N

participants

=

58),

24,28

and an information only control group

(N

studies

= 1; N

participants

= 60),

29

whereby the control

participants received the same written information

on spinal cord injury and access to community

resources as their telecounselling counterparts. In all

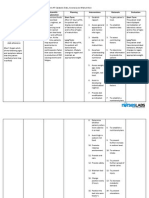

Potentially relevant studies identified

and screened

(n = 1084; duplicates removed)

Studies excluded off topic

(n = 43)

Telecounselling studies excludeddue

to sample characteristics, i.e. included

other chronic illness/disabilities,

>18 years (n = 39)

Studies included in systematic review

(n = 7)

Studies excluded due to intervention

characteristics, i.e. not

telecounselling

(n = 245)

Studies retrieved for more detailed

evaluation

(n = 1041)

Telecounselling studies excluded due to

design, i.e. qualitative or descriptive

stud with no treatment

evaluation (n = 7)

Studies excluded nil intervention

(n = 743)

Figure 1. Flowchart of study selection.

1076 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(12)

three studies,

24,28,29

check-in telephone or face-to-

face contact was available to control participants on

a needs basis.

Twenty different psychological and functional

measures were used to evaluate treatment effi-

cacy. These assessed depression, anxiety, stress,

quality of life, coping, hope, self-efficacy life sat-

isfaction, and aspects of community integration,

such as social and occupational functioning.

14,3046

Two studies

24,27

supplemented self-report mea-

sures with standardized clinical interviews,

namely the Mini International Neuropsychiatric

Interview

30

and Structural Clinical Interview for

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders IV.

31

Clinical characteristics of telephone-

based counselling

While all seven studies used the telephone to some

degree, six utilized the telephone as a primary treat-

ment modality.

2326,28,29

In addition, Phillips and col-

leagues

28

compared the efficacy of two treatment

arms a telephone programme and an audio-video

counselling programme to each other and to a

usual-care control group (Table 1).

The six telephone programmes

2326,28,29

involved

preventative interventions designed to maximize

psychosocial adjustment in the early transition

period (i.e. 612 months) following injury (Table

1). In contrast, Schulz and colleagues

29

examined

the effectiveness of a telephone counselling inter-

vention 58 years following primary rehabilita-

tion. The telephone interventions were relatively

modest in scope, involving weekly or fortnightly

sessions (N

studies

= 5) or a graduated programme of

weekly, followed by fortnightly or monthly ses-

sions (N

studies

= 1) delivered over a 912 week

period (Table 1).

Telephone-based counselling offered flexible

treatment options, being utilized for different psy-

chological therapies, including supportive counsel-

ling (N

studies

= 3),

23,25,28

cognitive behaviour therapy

(N

studies

= 2)

26,29

and motivational interviewing

(N

studies

= 1),

24

and by various health professionals

(e.g. peers, nurses, social workers, psychologists)

(Table 1). The research predominantly involved

individual-based telephone interventions, with one

study

29

utilizing both individual and group formats

to deliver a psycho-educational and coping skills

programme.

Treatment efficacy and process

outcomes of telephone counselling

Cohens d effect sizes indicate that only one study

achieved a statistically meaningful treatment effect

(i.e. confidence intervals did not span zero) immedi-

ately following telephone counselling (Table 2

online).

29

This study found a moderate improve-

ment in participants ability to manage physical

health symptoms related to spinal cord injury (e.g.

muscle pain, poor sleep patterns).

29

The remaining

studies

2326,28

were associated with moderate to

large, but non-significant, short-term treatment

effects for a range of psychosocial measures.

Interestingly, based on their own calculation of

p-values, some of these studies had reported statisti-

cally significant improvements in coping skills,

24

hope,

26

social functioning

26

or cognitive ability.

23

This discrepancy (effect sizes versus statistical test-

ing: confidence intervals versus p-values) confirms

the importance of examining both clinical and sta-

tistical significance.

21

Very limited data were available to evaluate

medium-term treatment effects (i.e. 312 months

post-telecounselling). Only two studies addressed

this question,

24,28

and their effect sizes varied con-

siderably (range: d = 0.160.88; Table 2 online). In

fact, the telecounselling programme used by Phillips

et al.

28

produced the only significant positive change

in quality of life ratings that was maintained 12

months after treatment cessation. All other treat-

ment effects, although positive, were small to mod-

erate in size and non-significant when followed up

at 3 and 12 months.

Clinical outcomes were reported by five stud-

ies

2426,28,29

and were generally favourable. The

mean attrition rate was 28%, although the range was

broad (SD 23.3%; range: 335%). The cost analy-

ses provided by Dorstyn et al.

24

indicate that tele-

phone counselling is cost-efficient, with the total

treatment cost per participant estimated at AU$150.

Participants in some studies also commented that

Dorstyn et al. 1077

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

S

u

m

m

a

r

y

d

e

t

a

i

l

s

o

f

a

l

l

s

t

u

d

i

e

s

i

n

c

l

u

d

e

d

i

n

t

h

e

c

u

r

r

e

n

t

r

e

v

i

e

w

(

N

s

t

u

d

i

e

s

=

7

)

.

L

e

a

d

a

u

t

h

o

r

M

e

t

h

o

d

o

l

o

g

y

T

e

l

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

p

r

o

g

r

a

m

m

e

d

e

t

a

i

l

s

S

a

m

p

l

e

s

i

z

e

D

e

s

i

g

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

d

m

e

a

s

u

r

e

s

E

v

i

d

e

n

c

e

l

e

v

e

l

(

G

r

a

d

e

)

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

a

i

m

s

K

e

y

t

h

e

r

a

p

i

s

t

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

f

o

r

m

a

t

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

m

o

d

e

l

S

e

s

s

i

o

n

f

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

a

n

d

d

u

r

a

t

i

o

n

S

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

M

e

d

i

u

m

S

c

h

u

l

z

2

9

(

2

0

0

9

)

1

1

4

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

(

5

7

i

n

j

u

r

e

d

i

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

s

;

5

7

c

a

r

e

r

s

)

6

0

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

R

a

n

d

o

m

i

z

e

d

M

u

l

t

i

c

e

n

t

r

e

t

r

i

a

l

B

l

i

n

d

e

d

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

I

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

-

o

n

l

y

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

C

E

S

-

D

S

e

l

f

-

c

a

r

e

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

s

H

e

a

l

t

h

s

y

m

p

t

o

m

s

S

o

c

i

a

l

i

n

t

e

g

r

a

t

i

o

n

S

o

c

i

a

l

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

2

(

B

)

P

r

o

m

o

t

e

h

e

a

l

t

h

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

a

n

d

p

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

w

e

l

l

-

b

e

i

n

g

P

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

s

t

G

r

o

u

p

a

n

d

i

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

a

n

d

f

a

c

e

-

t

o

-

f

a

c

e

C

o

g

n

i

t

i

v

e

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

t

h

e

r

a

p

y

a

n

d

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

i

v

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

7

i

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

(

5

f

a

c

e

-

t

o

-

f

a

c

e

a

n

d

2

p

h

o

n

e

c

a

l

l

s

,

6

0

9

0

m

i

n

p

e

r

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

)

a

n

d

5

g

r

o

u

p

p

h

o

n

e

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

.

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

d

e

l

i

v

e

r

e

d

o

v

e

r

6

m

o

n

t

h

s

P

h

i

l

l

i

p

s

2

8

(

2

0

0

1

)

3

6

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

(

p

h

o

n

e

)

3

6

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

(

v

i

d

e

o

)

3

9

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

R

a

n

d

o

m

i

z

e

d

U

s

u

a

l

c

a

r

e

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

Q

W

B

C

E

S

-

D

2

(

B

)

P

r

o

m

o

t

e

h

e

a

l

t

h

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

a

n

d

p

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

w

e

l

l

-

b

e

i

n

g

N

u

r

s

e

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

a

n

d

v

i

d

e

o

P

s

y

c

h

o

-

e

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

i

v

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

7

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

(

3

0

4

0

m

i

n

p

e

r

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

)

o

v

e

r

9

w

e

e

k

s

(

5

w

e

e

k

l

y

a

n

d

2

f

o

r

t

n

i

g

h

t

l

y

D

o

r

s

t

y

n

2

4

(

2

0

1

2

)

2

0

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

1

9

C

o

n

t

r

o

l

R

a

n

d

o

m

i

z

e

d

B

l

i

n

d

e

d

a

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

U

s

u

a

l

c

a

r

e

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

D

A

S

S

-

2

1

M

D

S

S

M

I

N

I

S

C

L

F

I

M

3

(

C

)

P

r

o

m

o

t

e

h

e

a

l

t

h

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

a

n

d

p

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

c

a

l

w

e

l

l

-

b

e

i

n

g

P

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

s

t

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

M

o

t

i

v

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

i

n

g

7

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

(

a

v

e

r

a

g

e

1

9

m

i

n

/

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

)

o

v

e

r

3

m

o

n

t

h

s

L

u

c

k

e

2

6

(

2

0

0

4

)

1

0

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

C

o

n

v

e

n

i

e

n

c

e

s

a

m

p

l

e

N

o

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

P

A

N

A

S

H

H

S

M

H

S

L

S

S

S

F

-

3

6

4

(

C

)

P

r

o

v

i

d

e

i

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

a

n

d

p

e

e

r

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

N

u

r

s

e

a

n

d

p

e

e

r

m

e

n

t

o

r

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

C

o

g

n

i

t

i

v

e

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

t

h

e

r

a

p

y

3

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

s

(

s

e

s

s

i

o

n

t

i

m

e

s

n

o

t

s

p

e

c

i

f

i

e

d

)

o

v

e

r

6

w

e

e

k

s

M

i

g

l

i

o

r

i

n

i

2

7

(

2

0

1

1

)

3

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

M

u

l

t

i

p

l

e

c

a

s

e

s

t

u

d

y

d

e

s

i

g

n

N

o

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

S

C

I

D

D

A

S

S

-

2

1

S

C

L

P

W

I

4

(

C

)

M

a

n

a

g

e

s

y

m

p

t

o

m

s

o

f

d

e

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

a

n

d

a

n

x

i

e

t

y

P

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

s

t

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

I

n

t

e

r

n

e

t

a

n

d

p

h

o

n

e

C

o

g

n

i

t

i

v

e

b

e

h

a

v

i

o

u

r

t

h

e

r

a

p

y

a

n

d

p

o

s

i

t

i

v

e

p

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

y

1

0

m

o

d

u

l

e

s

(

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

1078 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(12)

L

e

a

d

a

u

t

h

o

r

M

e

t

h

o

d

o

l

o

g

y

T

e

l

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

p

r

o

g

r

a

m

m

e

d

e

t

a

i

l

s

S

a

m

p

l

e

s

i

z

e

D

e

s

i

g

n

P

u

b

l

i

s

h

e

d

m

e

a

s

u

r

e

s

E

v

i

d

e

n

c

e

l

e

v

e

l

(

G

r

a

d

e

)

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

a

i

m

s

K

e

y

t

h

e

r

a

p

i

s

t

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

f

o

r

m

a

t

T

h

e

r

a

p

y

m

o

d

e

l

S

e

s

s

i

o

n

f

r

e

q

u

e

n

c

y

a

n

d

d

u

r

a

t

i

o

n

S

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

M

e

d

i

u

m

B

a

l

c

a

z

a

r

2

3

(

2

0

1

1

)

2

8

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

N

o

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

C

H

A

R

T

4

(

C

)

P

r

o

v

i

d

e

i

n

f

o

r

m

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

a

n

d

p

e

e

r

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

P

e

e

r

m

e

n

t

o

r

s

u

p

e

r

v

i

s

e

d

b

y

s

o

c

i

a

l

w

o

r

k

e

r

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

a

n

d

f

a

c

e

-

t

o

-

f

a

c

e

P

s

y

c

h

o

-

e

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

i

v

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

W

e

e

k

l

y

c

o

n

t

a

c

t

f

o

r

1

h

o

u

r

o

v

e

r

1

2

m

o

n

t

h

s

6

1

%

p

h

o

n

e

c

o

n

t

a

c

t

a

n

d

3

9

%

f

a

c

e

-

t

o

-

f

a

c

e

L

j

u

n

g

b

e

r

g

2

5

(

2

0

1

1

)

2

4

T

r

e

a

t

m

e

n

t

N

o

c

o

n

t

r

o

l

G

S

E

F

4

(

C

)

E

n

h

a

n

c

e

s

e

l

f

-

e

f

f

i

c

a

c

y

a

n

d

p

r

o

v

i

d

e

p

e

e

r

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

P

e

e

r

m

e

n

t

o

r

s

u

p

e

r

v

i

s

e

d

b

y

p

s

y

c

h

o

l

o

g

i

s

t

I

n

d

i

v

i

d

u

a

l

P

h

o

n

e

a

n

d

f

a

c

e

-

t

o

-

f

a

c

e

P

s

y

c

h

o

-

e

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

a

n

d

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

i

v

e

c

o

u

n

s

e

l

l

i

n

g

W

e

e

k

l

y

c

o

n

t

a

c

t

f

o

r

3

m

o

n

t

h

s

,

f

o

l

l

o

w

e

d

b

y

b

i

w

e

e

k

l

y

c

o

n

t

a

c

t

f

o

r

3

m

o

n

t

h

s

,

a

n

d

m

o

n

t

h

l

y

c

o

n

t

a

c

t

f

o

r

6

m

o

n

t

h

s

.

C

E

S

-

D

,

C

e

n

t

r

e

f

o

r

E

p

i

d

e

m

i

o

l

o

g

i

c

S

t

u

d

i

e

s

D

e

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

S

c

a

l

e

1

4

;

S

e

l

f

-

c

a

r

e

p

r

o

b

l

e

m

s

3

6

;

H

e

a

l

t

h

s

y

m

p

t

o

m

s

3

6

;

S

o

c

i

a

l

i

n

t

e

g

r

a

t

i

o

n

3

6

;

S

o

c

i

a

l

s

u

p

p

o

r

t

3

6

;

C

H

A

R

T

,

C

r

a

i

g

H

a

n

d

i

c

a

p

A

s

s

e

s

s

m

e

n

t

a

n

d

R

e

p

o

r

t

i

n

g

T

e

c

h

n

i

q

u

e

3

4

;

D

A

S

S

-

2

1

,

D

e

p

r

e

s

s

i

o

n

A

n

x

i

e

t

y

S

t

r

e

s

s

S

c

a

l

e

s

h

o

r

t

f

o

r

m

3

2

;

F

I

M

,

F

u

n

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

I

n

d

e

p

e

n

d

e

n

c

e

M

e

a

s

u

r

e

3

7

;

M

D

S

S

,

M

u

l

t

i

d

i

m

e

n

s

i

o

n

a

l

M

e

a

s

u

r

e

o

f

S

o

c

i

a

l

S

u

p

p

o

r

t

3

8

;

M

I

N

I

,

I

n

t

e

r

n

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

N

e

u

r

o

p

s

y

c

h

i

a

t

r

i

c

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

3

0

;

S

C

L

,

S

p

i

n

a

l

C

o

r

d

L

e

s

i

o

n

Q

u

e

s

t

i

o

n

n

a

i

r

e

s

3

3

;

Q

W

B

,

Q

u

a

l

i

t

y

o

f

W

e

l

l

-

B

e

i

n

g

S

c

a

l

e

3

9

;

P

A

N

A

S

,

P

o

s

i

t

i

v

e

a

n

d

N

e

g

a

t

i

v

e

A

f

f

e

c

t

S

c

a

l

e

4

0

;

H

H

S

,

H

e

r

t

h

H

o

p

e

S

c

a

l

e

4

1

;

M

H

S

,

M

i

l

l

e

r

H

o

p

e

S

c

a

l

e

4

2

;

L

S

S

,

L

i

f

e

S

i

t

u

a

t

i

o

n

S

u

r

v

e

y

4

3

;

S

F

-

3

6

,

M

e

d

i

c

a

l

O

u

t

c

o

m

e

s

S

t

u

d

y

S

h

o

r

t

-

F

o

r

m

H

e

a

l

t

h

S

u

r

v

e

y

4

4

;

S

C

I

D

,

S

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

a

l

C

l

i

n

i

c

a

l

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

f

o

r

D

S

M

D

i

s

o

r

d

e

r

s

3

7

;

P

W

I

,

P

e

r

s

o

n

a

l

W

e

l

l

b

e

i

n

g

I

n

d

e

x

;

4

5

G

S

E

F

,

G

e

n

e

r

a

l

i

s

e

d

P

e

r

c

e

i

v

e

d

S

e

l

f

-

E

f

f

i

c

a

c

y

S

c

a

l

e

.

4

6

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

(

C

o

n

t

i

n

u

e

d

)

Dorstyn et al. 1079

the intervention increased their sense of interper-

sonal support and reduced isolation.

23,26,28

Also interesting are the findings relating to tele-

counselling for diverse cultural groups. Participants

in Lucke and colleagues trial,

26

which targeted

Hispanics and African-Americans, reported that

telecounselling provided much-needed social sup-

port following primary spinal cord injury rehabilita-

tion. Similarly, Balcazar and colleagues

23

claimed

that matching their peer-mentors to mentees (n =

28) on the basis of race maximized improvements in

community integration (e.g. social roles and rela-

tionships). However, these qualitative data need to

be interpreted cautiously, given that both studies

examined small samples and were uncontrolled

(Table 2 online).

Clinical characteristics of video-based

counselling

Only one study examined the specific application of

video technology to counseling services in spinal

rehabilitation.

28

This study utilized videoconferenc-

ing to provide a nine-week nurse-led supportive

counselling programme to individuals with a newly

acquired injury who were not otherwise accessing

mental health services (Table 1).

Treatment efficacy and process

outcomes of video counselling

The short-term efficacy of video-based counsel-

ling could not be determined from this single trial,

because only post-intervention assessments were

conducted.

28

At 12-month follow-up, d-values

indicated that participants who completed the vid-

eocounselling programme reported significantly

more depression symptoms than those in the tele-

phone-only or standard-care conditions (Table 2

online).

28

Medium-term improvements were, however,

noted in relation to videoconferencing. Specifically,

these participants reported the lowest rehospitaliza-

tion rates, averaging 3 hospital-days per year, com-

pared with participants who received telephone

counselling (5 days per year) or standard care (8

days per year).

28

Thus, although there did not appear

to be any sustained psychological benefits from vid-

eocounselling, there appear to have been some

broader medical benefits. The authors

28

also

reported that videoconferencing was cost effective,

although formal costings were not included.

Clinical characteristics of internet-

based counselling

The study by Migliorini et al.

27

was the only evalu-

ation of an internet-delivered psychological pro-

gramme. Unlike the programmes reviewed above,

this intervention targeted a very small number of

adults (n = 3) in the chronic stage of spinal rehabili-

tation (mean time since diagnosis = 32.3 years, SD

= 11.9; range: 2745 years) but has informed a

larger scale randomized controlled trial that is cur-

rently underway.

27

The online programme, known

as ePACT, involved 10 self-administered modules,

addressing symptoms of depression and anxiety

using cognitive behavioural therapy and positive

psychology (Table 1). In addition to the standard-

ized intervention, email and telephone access to a

therapist were available, as needed.

Treatment efficacy and process

outcomes of internet counselling

Although the short-term treatment gains associated

with ePACT were moderate to large, they were not

statistically significant across the measures of

depression, anxiety and stress (Table 2 online).

27

Similarly, large to very large but non-significant

improvements were noted for injury-specific coping

strategies, including participants attitude towards

their disability and reduced sense of helplessness

(Table 2 online). Notably, these results were associ-

ated with large confidence intervals, indicating wide

variation in the treatment effects for individual cases

and rendering otherwise important treatment effects

non-significant. Nevertheless, the findings from this

study are promising, with all three participants

reporting non-clinical levels of depression, anxiety

and/or stress at the end of the intervention compared

to baseline.

27

Whether these clinical gains were

maintained over time remains unanswered because

follow-up assessments were not conducted.

1080 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(12)

Qualitative data from this study indicated that

participants considered the intervention to be con-

venient and acceptable, commenting that they

would not have otherwise accessed psychological

therapy due to the perceived stigma associated with

mental health services and/or transport access issues

related to physical disability.

27

Furthermore, partici-

pants reported that the availability of a therapist by

telephone contributed to the programmes appeal.

27

However, there was a high attrition rate, with 63%

(n = 5) of eligible participants withdrawing from the

programme due to conflicting time commitments or

a perception that they did not require psychological

support.

27

Consequently, these results should be

treated with caution.

Discussion

Results from the seven independent clinical stud-

ies

2329

included in this review are clinically promis-

ing, with telecounselling contributing to significant

short-term improvements in health symptoms for

individuals with spinal cord injuries.

29

However, the

longer term impact of telecounselling has yet to be

adequately evaluated. The few trials

24,28

that report

this data suggest that early treatment gains may not

be maintained.

Where available, the clinical outcome data sug-

gest that telecounselling can improve psychological

outcomes of this population in a time- and cost-

efficient way, with the majority of treatments (N

studies

= 5)

2326,28

delivered within the first three months

post discharge from primary rehabilitation.

However, these findings can only be considered ten-

tative: based on a small number of studies, most of

which utilized non-randomized and uncontrolled

trials (N

studies

= 4)

23,2527

with highly variable sample

sizes (sample size range: 3104).

Our results are largely consistent with those of

other telecounselling trials within chronic illness and

disability groups, which report that telephone- and

video-based counselling services provide an effec-

tive and efficient treatment option for managing

mood disorders in individuals with traumatic brain

injuries

47

or chronic medical conditions.

48,49

Telecounselling may facilitate routine psychological

follow-up of individuals with a newly acquired

injury, who often experience increased apprehension

and distress during the transition from primary reha-

bilitation.

4,28

However, additional information on the

delivery-related outcomes of telecounselling is

needed, with very few cost analyses currently avail-

able. These cost analyses need to include the total

amount of therapist contact time per participant, and

investigate clinician and patient attitudes towards the

different technology-assisted counselling services.

4

Given these potential clinical benefits, it may

be argued that telecounselling can provide com-

munity-based practitioners more opportunity to

efficiently monitor patients long-term psychologi-

cal health.

50

This is consistent with current models

of mental healthcare, favouring a biopsychosocial

approach in which periodic maintenance sessions

allow psychological problems to be monitored and

treated before they become more serious and

established.

1,50,51

Although the findings of this review are both

interesting and important, some limitations need to

be considered. First, the research designs that were

used by the current studies limit any causal state-

ments that can be made about the effectiveness of

telecounselling.

21

In particular, Balcazar et al.,

23

Ljungberg et al.,

25

Lucke et al.

26

and Migliorini

et al.

27

did not use control groups, consequently

spontaneous recovery/decline and the impact of hav-

ing some on-going contact (regardless of its content)

could not be assessed. A suitable control condition

might involve delivering the same tele-programme

in a face-to-face setting, which would control for

both of these effects while also enabling an evalua-

tion of whether the intervention content can be suc-

cessfully delivered via telecommunication

technology. Indeed this design has been adopted

among other telecounselling trials targeting, care-

givers of individuals with a spinal cord injury,

52

but

was only adopted by one reviewed study.

29

Moreover,

the four quasi-experimental studies

23,2527

all used

relatively small samples, limiting their statistical

power to detect significant effects.

19,21

Future trials

should therefore compute post-hoc power analy-

ses.

53

Estimates of treatment effects (i.e. Cohens d),

and tests of statistical significance (i.e. confidence

intervals for d-values), should also be routinely

Dorstyn et al. 1081

Clinical messages

Telecounselling has potential to provide a

community-based method by which to man-

age and treat a range of psychological issues

following spinal cord injury; thus reducing

depression and improving quality of life.

Telecounselling is practical to deliver and

generally accepted by consumers.

Further research using randomized controlled

trials and well controlled case studies are

needed to confirm the efficacy of telecounsel-

ling in the psychosocial care of people with

spinal cord injury and to define the minimum

requirements needed to achieve efficacy (e.g.

number and duration of sessions).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding

agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

*References with an asterisk are those included in the systematic

review

1. Campos B. Telepsychology and telecounselling: counsel-

ling conducted in a technology environment. Counsel Psy-

chother Health 2009; 5: 2659.

2. Bloemen-Vrencken JH, de Witte LP and Post MWM.

Follow-up care for persons with spinal cord injury living

in the community: a systematic review of interventions

and their evaluations. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 462475.

3. DeJong G, Hoffman J, Meade MA, et al. Post-rehabilitation

health care for individuals with SCI: extending health care

in the community. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil 2011; 17:

4658.

4. Dorstyn DS, Mathias JL and Denson LA. Psychosocial out-

comes of telephone-based counselling for adults with an

acquired physical disability: a meta-analysis. Rehabil Psy-

chol 2011; 56: 114.

5. Krause JS, Saunders LL and Newman S. Posttraumatic

stress disorder and spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Reha-

bil 2010; 91: 11821187.

6. Bloemen-Vrencken JH, de Witte LP and Post MWM. Fol-

low-up care for persons with spinal cord injury living in the

community: a systematic review of interventions and their

evaluations. Spinal Cord 2005; 43: 462475.

reported.

21

As was apparent here, effect sizes may be

better measures of clinical significance than

P-values.

Second, unreported confounding variables may

have mediated and moderated study outcomes.

Specifically, variables known to have a positive

impact on the effectivenesss of psychological inter-

ventions in spinal rehabiliation, such as concurrent

pharmacotherapy, were not always reported.

54

Similarly, some variables known to affect post-

injury depression or functional outcomes (e.g. pre-

existing psychiatric illness

5,54

or injury-related

neuropathic pain

55

) were largely unreported. The

single trial

28

that compared telephone- and video-

counselling reported an increase over time in

depression symptoms among videoconferencing

participants, compared to participants in telephone-

only or standard-care conditions. The authors

argued that between-group differences in psychiat-

ric comorbidities and antidepressant medications

may have impacted on patients responses to the

two interventions.

28

Likewise, Dorstyn et al.

24

sug-

gested pain as a possible moderator, because the

majority of their telephone-counselling sample used

long-term prescription medication for neuropathic

pain.

Third, the timing of assessments may have influ-

enced the estimated treatment effects. Balcazar

et al.,

23

Ljungberg et al.

25

and Schulz et al.

29

obtained

baseline data during an initial treatment phase involv-

ing face-to-face therapy. Similarly Phillips et al.

28

did

not include baseline assessments administered pre-

telecounselling in their study. Consequently, their

results may not accurately reflect the effectiveness of

telecounselling alone.

Finally, future trials need to examine longer

treatment durations and extended service delivery,

to determine treatment efficacy for more severe

psychopathology. The trials evaluated by Dorstyn

et al.

24

and Migliorini et al.

27

included individuals

with clinical levels of depression or anxiety at

baseline, but both interventions were relatively

short-term (three months). Consequently, the

small and non-significant treatment effects may

reflect the fact that short-term interventions can-

not meet or resolve more complex mental health

needs.

4

1082 Clinical Rehabilitation 27(12)

7. World Health Organization. The global burden of disease:

2004 update. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2008.

8. Hornblow AR. The evolution and effectiveness of tele-

phone counselling services. Hosp Community Psychiatry

1986; 37: 731733.

9. Kairy D, Lehoux P, Vincent C and Visintin M. A systematic

review of clinical outcomes, clinical process, healthcare uti-

lization and costs associated with telerehabilitation. Disabil

Rehabil 2009; 31: 427447.

10. Hersh WR, Helfand M, Wallace J, et al. Clinical outcomes

resulting from telemedicine interventions: a systematic

review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2001; 1: 512.

11. Rogante M, Grigioni M, Cordella D and Giacomozzi C. Ten

years of telerehabilitation: a literature overview of technol-

ogies and clinical applications. NeuroRehabilitation 2010;

27: 287304.

12. Schwartz SM, Trask PC, Shanmugham K and Townsend

CO. Conducting psychological research in medical settings:

challenges, limitations and recommendations for effective-

ness research. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2004; 35: 500508.

13. Kerstein P, Ellis-Hill C, McPherson KM and Harrington R.

Beyond the RCT: understanding the relationship between

interventions, individuals and outcome. Disabil Rehabil

2010; 32: 10281034.

14. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self report depression

scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol

Meas 1977; 1: 385400.

15. Oxford Centre for Evidence Based Medicine Levels of

Evidence Working Group. The Oxford 2011 Levels of Evi-

dence, 2011. www.cebm.net/index.aspx?o=5653 (accessed

1 November 2012).

16. Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB and

Richardson WS. Evidence-based medicine: what it is and

what it isnt. BMJ 1996; 312: 7172.

17. Higgins JPT and Green S (eds). Cochrane handbook for

systematic reviews of interventions, version 5.0.2. The

Cochrane Collaboration, 2009. www.cochrane-handbook.

org (accessed 1 November 2012)

18. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA state-

ment for reporting systematic reviews and metaanalyses of

studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation

and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009; 6: e1000100.

19. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull 1991; 112: 155

159.

20. Morris SB and DeShon RP. Combining effect size estimates

in meta-analysis with repeated measures and independent-

groups designs. Psychol Meth 2002; 7: 105125.

21. Lipsey MW and Wilson DB. Practical meta-analyses. Lon-

don: Sage, 2001.

22. Sharpe D. Of apples and oranges, file drawers and garbage:

why validity issues in meta-analysis will not go away. Clin

Psychol Rev 1997; 17: 881901.

23. *Balcazar FE, Kelly EH, Beys CB and Balfanx-Vretiz K.

Using peer mentoring to support the rehabilitation of indi-

viduals with violently acquired spinal cord injuries. J Appl

Rehabil Counsel 2011; 42: 311.

24. *Dorstyn DS, Mathias JL, Denson LA and Robertson TM.

Effectiveness of telephone counselling in managing psy-

chological outcomes following spinal cord injury: a prelim-

inary study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 93: 21002108.

25. *Ljungberg I, Kroll T, Libin A and Gordon S. Using peer

mentoring for people with spinal cord injury to enhance

self-efficacy beliefs and prevent medical complications. J

Clin Nurs 2011; 20: 351358.

26. *Lucke KT, Lucke JF and Martinez H. Evaluation of a pro-

fessional and peer telephone intervention with spinal cord

injured individuals following rehabilitation in South Texas.

J Multicult Nurs Health 2004; 10: 6874.

27. *Migliorini C, Tonge B and Sinclair A. Developing and

piloting ePACT: a flexible psychological treatment for

depression in people living with chronic spinal cord injury.

Behav Change 2011; 28: 4554.

28. *Phillips VL, Vesmarovich S, Hauber R, Wiggers E and

Egner A. Telecounselling: reaching out to newly injured

spinal cord patients. Public Health Rep 2001; 116: 94102.

29. *Schulz R, Czaja SJ, Lustig A, Zdaniuk B, Martire LM and

Perdomo D. Improving the quality of life of caregivers of

persons with spinal cord injury: a raandomised controlled

trial. Rehabil Psychol 2009; 51: 115.

30. Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y and Sheehan KH. The MINI

International Neuropsychiatric Interview: the development

and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric inter-

view. J Clin Psychiatry 1998; 59 (suppl 20): 2223.

31. First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M and Williams JBW. Struc-

tured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I disorders,

research version, non-patient edition (SCID-I/NP). New

York: Biometrics Research New York State Institute, 2002.

32. Lovibond SH and Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression

Anxiety Stress Scales, second edition. Sydney: Psychology

Foundation of Australia, 2001.

33. Migliorini C, Elfstrm ML and Tonge BL. Translation and

Australian validation of the spinal cord lesion related cop-

ing strategies and emotional well-being questionnaires. Spi-

nal Cord 2008; 46: 690695.

34. Whiteneck GG, Charlifue SW, Gerhart KA, Overholser JD

and Richardson GN. Quantifying handicap: a new measure

of long-term rehabilitation outcomes. Arch Phys Med Reha-

bil 1992; 73: 519526.

35. Burton L, Schulz R, Jackson S, Hirsch C and Zdaniuk B.

Transitions in spousal caregiving: experience from the

caregiver health effects study. Gerontologist 2000; 43:

230241.

36. Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al., for the Resources for

Enhancing Alzheimers Caregiver Health (REACH) II

Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia

caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups. Ann Intern

Med 2006; 145: 727738.

37. Hamilton BB, Granger CB, Sherwin FS, Zeilezny M and

Tashman JS. Uniform national data system for medi-

cal rehabilitation. In: Fuhrer MJ (ed.) Rehabilitation out-

comes: analysis and measurement. Baltimore, MD: Paul H.

Brookes Publishing, 1987, pp. 137147.

Dorstyn et al. 1083

38. Winefield HR, Winefield AH and Tiggeman M. Social sup-

port and psychological well-being in young adults. J Pers

Assess 1992; 58: 198210.

39. Kaplan BJ, Bush JW and Berry CC. Health status: types of

validity for the index of well-being. Health Serv Res 1976;

11: 478507.

40. Watson D, Clark LA and Tellegen A. Development and

validation of brief measures of positive and negative

affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988; 54:

10631070.

41. Herth K. Development and refinement of an instrument to

measure hope. Schol Inq Nurs Pract 1991; 5: 3951.

42. Miller JF and Power MJ. Development of an instrument to

measure hope. J Nurs Res 1988, 37: 610.

43. Chubon RA. Manual for the Life Satisfaction Survey.

Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina, School of

Medicine, Department of Neuropsychiatry and Behavior

Science, Rehabilitation Counseling Program, 1995.

44. Ware JE and Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-

form health survey (SF-46). Med Care 1992; 30:

473483.

45. International Wellbeing Group. Personal wellbeing index.

Melbourne, Australia: Australian Quality of Life, Deakin

University, 2006. www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/

instruments/wellbeing_index.htm (accessed 1 November

2012).

46. Jerusalem M and Schwarzer R. Self-efficacy as a resource

factor in stress-appraisal process. In: Schwarzer R (ed.)

Self-efficacy: thought control of action. Washington, DC:

Hemisphere, 1992: 195211.

47. Bombardier C, Bell KR, Temkin A, Fann JR, Hoffman JM

and Dikmen S. The efficacy of a scheduled telephone inter-

vention for ameliorating depressive symptoms during the

first year after traumatic brain injury. J Head Trauma Reha-

bil 2009; 24: 230238.

48. Bombardier C, Cunniffe M, Wadhwani R, Gibbons LE,

Blake KD and Kraft GH. The efficacy of telephone counsel-

ling for health promotion in people with multiple sclerosis:

a randomised controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2008;

89: 18491856.

49. Mohr DC, Likowsky W, Bertagnolli A, et al. Telephone-

administered cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment

of depressive symptoms in multiple sclerosis. J Consult

Clin Psychol 2000; 68: 356361.

50. Kazdin AE and Blase SL. Rebooting psychotherapy

research and practice to reduce the burden of mental illness.

Perspect Psychol Sci 2011; 6: 2137.

51. Mozer E, Franklin B and Rose J. Psychotherapeutic inter-

vention by telephone. Clin Interv Aging 2008; 3: 391396.

52. Elliott TR and Berry JW. Brief problem solving training for

family caregivers of peresons with recent-onset spinal cord

injuries: a randomised controlled trial. J Clin Psychol 2009;

65: 406422.

53. Abdul Latif L, Daud Amadera JE, Pimentel D, Pimentel T

and Fregni F. Sample size calculation in physical medicine

and rehabilitation: a systematic review of reporting, char-

acteristics and results in randomised controlled trials. Arch

Phys Med Rehabil 2011; 92: 306315.

54. Tuszyinski MH, Steeves JD, Fawcett JW, et al. Guidelines

for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury as

developed by the ICCP panel: clinical trial inclusion/exclu-

sion criteria and ethics. Spinal Cord 2007; 45: 222231.

55. Nicholson Perry K and Middleton J. Comparison of a pain

management program with usual care in a pain management

centre for people with spinal cord injury-related chronic

pain. Clin J Pain 2010; 26: 206216.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Benefit The Acute Patient Pathway: A Mixed-Methods StudyDokument12 SeitenOccupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Benefit The Acute Patient Pathway: A Mixed-Methods StudyIlvita MayasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Telehealth Approach To Oropharyngeal Dysphagia TherapyDokument5 SeitenA Telehealth Approach To Oropharyngeal Dysphagia TherapyHeriberto Aguirre MenesesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example of PHD Research ProposalDokument2 SeitenExample of PHD Research ProposalMuhammad Khurram ShahzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Telehealth in Audiology: An Integrative ReviewDokument8 SeitenTelehealth in Audiology: An Integrative ReviewRUBÉN TOMÁS CRUZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Content ServerDokument14 SeitenContent ServerDilfera HermiatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prelim Exam Block 2 Group 3Dokument5 SeitenPrelim Exam Block 2 Group 3Sufina AnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Metaanalisis Castro Et Al. 2019Dokument37 SeitenMetaanalisis Castro Et Al. 2019LauraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bommersbach (2021) - Mental Health Staff Perceptions of Improvement Opportunities Around Covid 19Dokument14 SeitenBommersbach (2021) - Mental Health Staff Perceptions of Improvement Opportunities Around Covid 19Maximiliano AzconaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Martino, D. (2023) - Treatment Failure in Persisten Tic Disorders...Dokument15 SeitenMartino, D. (2023) - Treatment Failure in Persisten Tic Disorders...cuautzinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of An Interdisciplinary Screening Program For People With Parkinson Disease and Movement DisordersDokument10 SeitenEvaluation of An Interdisciplinary Screening Program For People With Parkinson Disease and Movement DisordersAbu Faris Al-MandariNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMC Pediatrics: Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Interventions For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewDokument10 SeitenBMC Pediatrics: Effectiveness of Physical Therapy Interventions For Children With Cerebral Palsy: A Systematic ReviewERICKNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yjmt 30 1992090Dokument13 SeitenYjmt 30 1992090Luis Sebastian Arango OspinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Treatment Schedule of Conventional Physical Therapy Provided To Enhance Upper Limb Sensorimotor Recovery After Stroke Expert Criterion Validity and Intra-Rater ReliabilityDokument10 SeitenA Treatment Schedule of Conventional Physical Therapy Provided To Enhance Upper Limb Sensorimotor Recovery After Stroke Expert Criterion Validity and Intra-Rater ReliabilityGeraldo MoraesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in Mentally Disordered Offender Pathway ForDokument38 SeitenImpact - Ijranss-1. Ijranss - Length of Stay Reporting in Forensic Secure Care Can Be Augmented by An Overarching Framework To Map Patient Journey in Mentally Disordered Offender Pathway ForImpact JournalsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Disfagia OFDokument13 SeitenDisfagia OFSebastián Contreras CubillosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Telehealth RirinDokument12 SeitenTelehealth RirinririnsityalfiahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Internet-Based Psycho-Educational Interventions On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Cancer PatientsDokument12 SeitenEffects of Internet-Based Psycho-Educational Interventions On Mental Health and Quality of Life Among Cancer PatientsflorgilNoch keine Bewertungen

- NGC 8208Dokument12 SeitenNGC 8208Alvaro Carlos Calvo ValenciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Investigating The Preferences of Older People For Telehealth As A New Model of Health Care Service Delivery: A Discrete Choice ExperimentDokument13 SeitenInvestigating The Preferences of Older People For Telehealth As A New Model of Health Care Service Delivery: A Discrete Choice Experimenttherese BNoch keine Bewertungen

- Health Care Professionals' Experiences and Perspectives On Using Telehealth For Home-Based Palliative Care: Protocol For A Scoping ReviewDokument7 SeitenHealth Care Professionals' Experiences and Perspectives On Using Telehealth For Home-Based Palliative Care: Protocol For A Scoping Reviewshaza ameliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complementary Therapies in Clinical PracticeDokument18 SeitenComplementary Therapies in Clinical PracticeNgaWa ChowNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homebasedtelehealth PDFDokument6 SeitenHomebasedtelehealth PDFdaniel serraniNoch keine Bewertungen