Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Calderon V Carale

Hochgeladen von

Trina Donabelle GojuncoOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Calderon V Carale

Hochgeladen von

Trina Donabelle GojuncoCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

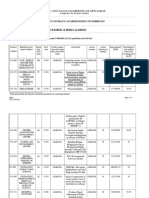

G.R. No. 91636 April 23, 1992 PETER JOHN D. CALDERON, petitioner, vs.

. BARTOLOME CARALE, in his capacity as Chairman of the National Labor Relations Commission, EDNA BONTO PEREZ, LOURDES C. JAVIER, ERNESTO G. LADRIDO III, MUSIB M. BUAT, DOMINGO H. ZAPANTA, VICENTE S.E. VELOSO III, IRENEO B. BERNARDO, IRENEA E. CENIZA, LEON G. GONZAGA, JR., ROMEO B. PUTONG, ROGELIO I. RAYALA, RUSTICO L. DIOKNO, BERNABE S. BATUHAN and OSCAR N. ABELLA, in their capacity as Commissioners of the National Labor Relations Commission, and GUILLERMO CARAGUE, in his capacity as Secretary of Budget and Management, respondents. FACTS: Sometime in March 1989, RA 6715 (Herrera-Veloso Law), amending the Labor Code was approved. It provides in Section 13 thereof as follows: xxx xxx xxx

The Chairman, the Division Presiding Commissioners and other Commissioners shall all be appointed by the President, subject to confirmation by the Commission on Appointments. Appointments to any vacancy shall come from the nominees of the sector which nominated the predecessor. The Executive Labor Arbiters and Labor Arbiters shall also be appointed by the President, upon recommendation of the Secretary of Labor and Employment, and shall be subject to the Civil Service Law, rules and regulations.

Pursuant to said law (RA 6715), President Aquino issued permanent appointments to the Chairman and Commissioners of the National Labor Relations Commission (NLRC), BUT WITHOUT confirmation from the Commission on Appointments. Peter John D. Calderon (petitioner), thus, filed a petition for prohibition. This petition for prohibition questions the constitutionality and legality of the permanent appointments extended by the President to the respondents Chairman and Members of the NLRC, without submitting the same to the Commission on Appointments for confirmation pursuant to RA 6715. Petitioner claims that the Mison and Bautista rulings are NOT decisive of the issue in this case for in the case at bar because of the passage of RA 6715 which requires the confirmation by the Commission on Appointments of such appointments. The Solicitor General, on the other hand, contends that RA 6715 transgresses Section 16, Article VII by expanding the confirmation powers of the Commission on Appointments WITHOUT constitutional basis. Had it been the intention to ALLOW Congress to expand the list of officers whose appointments must be confirmed by the Commission on Appointments, the Constitution would have said so by adding the phrase "and other officers required by law" at the end of the first sentence, OR the phrase, "with the consent of the Commission on Appointments" at the end of the second sentence. Evidently, our Constitution has significantly omitted to provide for such additions. The controversy is focused on this provision in the 1987 Constitution:

Sec. 16. The President shall nominate and, with the consent of the Commission on Appointments, appoint the heads of the executive departments, ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, or officers of the armed forces from the rank of colonel or naval captain, and other officers whose appointments are vested in him in this Constitution. He shall also appoint all other officers of the Government whose appointments are not otherwise provided for by law, and those whom he may be authorized by law to appoint. The Congress may, by law, vest the appointment of other officers lower in rank in the President alone, in the courts, or in the heads of departments, agencies, commissions, or boards. The President shall have the power to make appointments during the recess of the Congress, whether voluntary or compulsory, but such appointments shall be effective only until disapproval by the Commission on Appointments or until the next adjournment of the Congress.

The power of the Commission on Appointments was construed in the cases of Sarmiento III vs. Mison, Mary Concepcion Bautista v. Salonga, and Teresita Quintos Deles, et al. v. The Commission on Constitutional Commissions, et al. From the 3 cases, these doctrines are deducible: 1. Confirmation by the Commission on Appointments is required ONLY: a. For presidential appointees mentioned in the first sentence of Section 16, Article VII (heads of the executive departments, ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, or officers of the armed forces from the rank of colonel or naval captain) b. And officers whose appointments are expressly vested by the Constitution itself in the president (sectoral

representatives to Congress and members of the constitutional commissions of Audit, Civil Service and Election) 2. Confirmation is NOT required WHEN president appoints: a. Other government officers whose appointments are NOT otherwise provided for by law (when Congress creates inferior offices but omits to provide for appointment thereto, or provides in an unconstitutional manner for such appointments) b. Those officers whom he may be authorized by law to appoint (Chairman and Members of the Commission on Human Rights) Issue: Whether or not Congress may, by law, require confirmation by the Commission on Appointments of appointments extended by the president to government officers additional to those expressly mentioned in the first sentence of Sec. 16, Art. VII of the Constitution Held: NO. There are 4 groups of officers whom the President shall appoint: 1. The heads of the executive departments, ambassadors, other public ministers and consuls, officers of the armed forces from the rank of colonel or naval captain, and other officers whose appointments are vested in him in this Constitution 2. All other officers of the Government whose appointments are not otherwise provided for by law; 3. Those whom the president may be authorized by law to appoint; 4. Officers lower in rank whose appointments the Congress may by law vest in the President alone. The 2nd sentence of Sec. 16, Art. VII refers to all other officers of the government whose appointments are not otherwise provided for by law and those whom the President may be authorized by law to appoint. Certainly, the NLRC Chairman and Commissioners fall within the 2nd sentence of Section 16, Article VII of the Constitution, more specifically under the 3rd group of appointees. To the extent that RA 6715 requires confirmation by the Commission on Appointments of the appointments of respondents Chairman and Members of the National Labor Relations Commission, it is unconstitutional because: 1) It amends by legislation, the 1st sentence of Sec. 16, Art. VII of the Constitution by adding thereto appointments requiring confirmation by the Commission on Appointments; and 2) It amends by legislation the 2nd sentence of Sec. 16, Art. VII of the Constitution, by imposing the confirmation of the Commission on Appointments on appointments which are otherwise entrusted only with the President. Deciding on what laws to pass is a legislative prerogative. Determining their constitutionality is a judicial function. The interpretation upon a law by the Court constitutes, in a way, a part of the law as of the date that law was originally passed, since this Court's construction merely establishes the contemporaneous legislative intent that the law thus construed intends to effectuate. The settled rule supported by numerous authorities is a restatement of the legal maxim " legis interpretado legis vim obtinent" the interpretation placed upon the written law by a competent court has the force of law. The rulings in Mison, Bautista and Quintos-Deles have interpreted Art. VII, Sec. 16 consistently in one manner. Can legislation expand a constitutional provision after the Supreme Court has interpreted it? NO!! In Endencia and Jugo vs. David, the Court held that the legislature cannot pass any declaratory act, or act declaratory of what the law was before its passage, so as to give it any binding weight with the courts. The legislature cannot, upon passing law which violates a constitutional provision, validate it so as to prevent an attack thereon in the courts, by a declaration that it shall be so construed as not to violate the constitutional inhibition. The legislature under our form of government is assigned the task and the power to make and enact laws, but not to interpret them. This is more true with regard to the interpretation of the basic law, the Constitution, which is not within the sphere of the Legislative department. Congress, of course, must interpret the Constitution, must estimate the scope of its constitutional powers when it sets out to enact legislation and it must take into account the relevant constitutional prohibitions. The deliberate limitation on the power of confirmation of the Commission on Appointments over presidential appointments, embodied in Sec. 16, Art. VII of the 1987 Constitution, has undoubtedly evoked the displeasure and disapproval of members of Congress. The solution to the apparent problem, if indeed a problem, is not judicial or legislative but constitutional. A future constitutional convention or Congress sitting as a constituent (constitutional) assembly may then consider either a return to the 1935 Constitutional provisions or the adoption of a hybrid system between the 1935 and 1987 constitutional provisions . Until then, it is the duty of the Court to apply the 1987 Constitution in accordance with what it says and not in accordance with how the legislature or the executive would want it interpreted.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Appointed by The President, Subject To Confirmation by The Commission On Appointments. Appointments ToDokument3 SeitenAppointed by The President, Subject To Confirmation by The Commission On Appointments. Appointments ToPat GalloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calderon V CaraleDokument2 SeitenCalderon V CaraleAlyanna BarreNoch keine Bewertungen

- 05) Garcia Vs COADokument3 Seiten05) Garcia Vs COAAlexandraSoledadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mantruste Systems VS CaDokument1 SeiteMantruste Systems VS CashelNoch keine Bewertungen

- CD 9. Gonzales Vs NarvasaDokument1 SeiteCD 9. Gonzales Vs Narvasajoe marieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jimenez v. Cabangbang, G.R. No. 15905, August 3, 1966Dokument1 SeiteJimenez v. Cabangbang, G.R. No. 15905, August 3, 1966Jay CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beltran V MacasiarDokument2 SeitenBeltran V MacasiarSocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Dept.: President - Power of Appointment Bermudez v. TorresDokument3 SeitenExecutive Dept.: President - Power of Appointment Bermudez v. TorresRein GallardoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bir Vs OmbudsDokument2 SeitenBir Vs OmbudsJoshua L. De JesusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dingcong Vs GuingonaDokument4 SeitenDingcong Vs GuingonaAbigael DemdamNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 78239 February 9, 1989 SALVACION A. MONSANTO, Petitioner, vs. FULGENCIO S. FACTORAN, JR., RespondentDokument1 SeiteG.R. No. 78239 February 9, 1989 SALVACION A. MONSANTO, Petitioner, vs. FULGENCIO S. FACTORAN, JR., Respondentjodelle11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Case DigestDokument4 SeitenCase DigestKrizel BianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- POLI CASE DIGESTS 8 Part 1 - Judiciary DepartmentDokument13 SeitenPOLI CASE DIGESTS 8 Part 1 - Judiciary DepartmentMai Reamico100% (2)

- CSC authority over local govt appointmentsDokument2 SeitenCSC authority over local govt appointmentsKris MercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- PNB Vs Dan PadaoDokument9 SeitenPNB Vs Dan PadaokimuchosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippine National Bank, Petitioner, vs. Dan Padao, Respondent. A. G.R. No. 180849Dokument18 SeitenPhilippine National Bank, Petitioner, vs. Dan Padao, Respondent. A. G.R. No. 180849amco88Noch keine Bewertungen

- Book Iv Obligations and Contracts Title. I. - Obligations General ProvisionsDokument149 SeitenBook Iv Obligations and Contracts Title. I. - Obligations General ProvisionsDak KoykoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 24 Manalo vs. Sistoza PDFDokument14 Seiten24 Manalo vs. Sistoza PDFshlm bNoch keine Bewertungen

- MTRCB vs ABS-CBN Supreme Court Ruling on Review of TV ProgramsDokument8 SeitenMTRCB vs ABS-CBN Supreme Court Ruling on Review of TV Programsvanessa3333333Noch keine Bewertungen

- Torayno V ComelecDokument4 SeitenTorayno V ComelecyanieggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legislative - Tolentino V Secretary of FinanceDokument3 SeitenLegislative - Tolentino V Secretary of FinanceNathalie Faye Abad ViloriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Republic of The Philippines, Represented by The Regional Executive Director, Region X, Department of Public Works and Highways, Petitioner, vs. Benjohn Fetalvero, Respondent.Dokument8 SeitenRepublic of The Philippines, Represented by The Regional Executive Director, Region X, Department of Public Works and Highways, Petitioner, vs. Benjohn Fetalvero, Respondent.Jiolo VelezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Santero v. CFI of CaviteDokument2 SeitenSantero v. CFI of CaviteFritz Frances DanielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- PEOPLE Vs LagmanDokument1 SeitePEOPLE Vs LagmanDerick BalangayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article 7 Section 19 Sabello V Department of EducationDokument5 SeitenArticle 7 Section 19 Sabello V Department of EducationOdessa Ebol Alpay - QuinalayoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diaz v. People GR 65006, Oct. 31, 1990: FactsDokument2 SeitenDiaz v. People GR 65006, Oct. 31, 1990: FactsJohn Lester LantinNoch keine Bewertungen

- United Overseas Bank of The Philippines, Inc., Petitioner V. J.O.S. Managing Builders, Inc. and EDUPLAN, INC., RespondentsDokument8 SeitenUnited Overseas Bank of The Philippines, Inc., Petitioner V. J.O.S. Managing Builders, Inc. and EDUPLAN, INC., RespondentsAko Si Paula MonghitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Serrano de Agbayani vs. PNB, 38 SCRA 429Dokument4 SeitenSerrano de Agbayani vs. PNB, 38 SCRA 429Inez Pads100% (1)

- Eminent Domain and the Taking of Private PropertyDokument12 SeitenEminent Domain and the Taking of Private PropertyPeace Marie PananginNoch keine Bewertungen

- The United States Vs Juan PonsDokument3 SeitenThe United States Vs Juan PonsMczoC.MczoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Balibago Faith Baptist Church V Faith in Christ Jesus Baptist ChurchDokument13 SeitenBalibago Faith Baptist Church V Faith in Christ Jesus Baptist ChurchRelmie TaasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Go Tek V Deportation BoardDokument1 SeiteGo Tek V Deportation Boardgelatin528Noch keine Bewertungen

- Liban v. GordonDokument7 SeitenLiban v. GordonIldefonso HernaezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obra Vs Sps BaduaDokument1 SeiteObra Vs Sps BaduaJeandee LeonorNoch keine Bewertungen

- 870 - IX - Luego v. CSC - 143 SCRA 327 (1986)Dokument1 Seite870 - IX - Luego v. CSC - 143 SCRA 327 (1986)ian100% (1)

- People vs. UdangDokument1 SeitePeople vs. UdangAthea Justine YuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trillanes IV vs. Castillo-MarigomenDokument38 SeitenTrillanes IV vs. Castillo-MarigomenMarvey MercadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 12 de Castro Vs JBCDokument3 Seiten12 de Castro Vs JBCJonny DuppsesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tañada vs. Tuvera ruling on publicationDokument27 SeitenTañada vs. Tuvera ruling on publicationcarl fuerzasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imbong vs. FerrerDokument1 SeiteImbong vs. FerrerKevin PasionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lagman Et. Al. V. Medialdea Et. Al., G.R. Nos. 231568/231771/231774, July 4, 2017Dokument2 SeitenLagman Et. Al. V. Medialdea Et. Al., G.R. Nos. 231568/231771/231774, July 4, 2017Brod LenamingNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Philconsa V MathayDokument33 Seiten5 Philconsa V MathayMary Joy JoniecaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filipino Citizen's Land Registration CaseDokument3 SeitenFilipino Citizen's Land Registration CaseAnneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consti 1 - Law Cases - The StateDokument43 SeitenConsti 1 - Law Cases - The StateVic CajuraoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 16 - People v. BeranaDokument2 Seiten16 - People v. BeranaalfredNoch keine Bewertungen

- Accfa Vs CugcoDokument2 SeitenAccfa Vs CugcoCamille CarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Go Tek Vs Deportation BoardDokument3 SeitenGo Tek Vs Deportation Boardlovekimsohyun89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tecson v. SandiganbayanDokument10 SeitenTecson v. Sandiganbayanneil borjaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Col Case Digest-ExecutiveDokument150 SeitenCol Case Digest-ExecutiveJake CastañedaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francisco V HorDokument2 SeitenFrancisco V HorPBWGNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 162230 Isabelita Vinuya, Et Al. vs. Executive Secretary Alberto G. Romulo, Et Al. by Justice Lucas BersaminDokument11 SeitenG.R. No. 162230 Isabelita Vinuya, Et Al. vs. Executive Secretary Alberto G. Romulo, Et Al. by Justice Lucas BersaminHornbook Rule100% (1)

- Pimentel Vs ErmitaDokument2 SeitenPimentel Vs ErmitaSapphireNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Phils Vs Garcia My DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople of The Phils Vs Garcia My DigestMichael Renz PalabayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atlas Fertilizer Corp vs. SecretaryDokument2 SeitenAtlas Fertilizer Corp vs. SecretaryAngelicaOrdonezNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAGCOR vs. Rilloraza PDFDokument16 SeitenPAGCOR vs. Rilloraza PDFFlorz Gelarz0% (1)

- ICC – RP-US Non-Surrender Pact UpheldDokument29 SeitenICC – RP-US Non-Surrender Pact UpheldReyshanne Joy B MarquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Francisco Vs HRDokument2 SeitenFrancisco Vs HRnikiboigeniusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mambulao Vs PNB (Adverse Effects of Forclosure Doesn - T Affect The Reputation of The Company - Attorney - S FeeDokument2 SeitenMambulao Vs PNB (Adverse Effects of Forclosure Doesn - T Affect The Reputation of The Company - Attorney - S FeeJM BanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR 91636Dokument13 SeitenGR 91636AM CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Petitioner vs. VS.: en BancDokument11 SeitenPetitioner vs. VS.: en BancDesai SarvidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AF Sanchez Brokerage IncDokument1 SeiteAF Sanchez Brokerage IncTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3.lacson Magallanes Co Inc V PanoDokument2 Seiten3.lacson Magallanes Co Inc V PanoTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (2)

- Constantino V HeirsDokument5 SeitenConstantino V HeirsTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kho Vs CA Et Al DigestDokument1 SeiteKho Vs CA Et Al DigestTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (3)

- Villanueva Vs Marlyn Nite DIGESTDokument1 SeiteVillanueva Vs Marlyn Nite DIGESTTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Query of Atty Karen Buffe DigestDokument2 SeitenQuery of Atty Karen Buffe DigestTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (5)

- Transpo - CAL Vs Chiok DIGESTDokument1 SeiteTranspo - CAL Vs Chiok DIGESTTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ang Vs Teodoro - TrademarkDokument2 SeitenAng Vs Teodoro - TrademarkTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Re Valenzuela and Vallarta DigestDokument2 SeitenIn Re Valenzuela and Vallarta DigestTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (7)

- Pangasinan Transport Co. vs. Public Service Commission Upholds Delegation of PowersDokument1 SeitePangasinan Transport Co. vs. Public Service Commission Upholds Delegation of PowersTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (2)

- US Vs Soliman - Case Digest - StatconDokument3 SeitenUS Vs Soliman - Case Digest - StatconTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (4)

- Que Po Lay DigestDokument1 SeiteQue Po Lay DigestTrina Donabelle GojuncoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orap Vs COMELEC Case Digest - ConstiDokument2 SeitenOrap Vs COMELEC Case Digest - ConstiTrina Donabelle Gojunco100% (2)

- E11 Publication of Award En-1-2-FinalDokument3 SeitenE11 Publication of Award En-1-2-Finalendriteta2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Power SharingDokument14 SeitenPower SharingSumit PandaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment: Name: - Aarishti Singh Contact No. - 8527492737Dokument6 SeitenAssignment: Name: - Aarishti Singh Contact No. - 8527492737Arishti SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Child Protection Policy Template ReportDokument2 SeitenChild Protection Policy Template ReportIyle100% (5)

- 10 BDRRMC Approving 2023Dokument2 Seiten10 BDRRMC Approving 2023Jervel Guanzon100% (1)

- Philippine SK Impact Assessement Conference 2012Dokument5 SeitenPhilippine SK Impact Assessement Conference 2012Marlon CornelioNoch keine Bewertungen

- TJagath Singh.Dokument7 SeitenTJagath Singh.aravind kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- 01b Declaration of Interest SBD4 PDFDokument4 Seiten01b Declaration of Interest SBD4 PDFs.PERINPANAYAGAMNoch keine Bewertungen

- BrosuraDokument4 SeitenBrosuradbatar100% (3)

- Trade Union Act 1926Dokument15 SeitenTrade Union Act 1926sanjuviewsonicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Authority To Solemnize MarriagesDokument1 SeiteAuthority To Solemnize MarriagesnuvelcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Achacoso Vs Macaraig.Dokument1 SeiteAchacoso Vs Macaraig.Lean FalcutilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PTF-CAGAYAN October 9, 2020 (With Significant Accomplishments of CMTFS)Dokument9 SeitenPTF-CAGAYAN October 9, 2020 (With Significant Accomplishments of CMTFS)michael ricafortNoch keine Bewertungen

- Birthright May 2011Dokument3 SeitenBirthright May 2011Pro Life CampaignNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distinctive Features of Federal ConstitutionDokument4 SeitenDistinctive Features of Federal Constitutionnelfiamiera50% (2)

- Certified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsDokument2 SeitenCertified List of Candidates For Congressional and Local Positions For The May 13, 2013 2013 National, Local and Armm ElectionsSunStar Philippine NewsNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Yours For Industrial Freedom" - Women of The IWW, 1905-1930 - ScholarSearch - Discovery Service For DRDokument57 Seiten"Yours For Industrial Freedom" - Women of The IWW, 1905-1930 - ScholarSearch - Discovery Service For DRindiousNoch keine Bewertungen

- Obligations and Contracts ReviewerDokument101 SeitenObligations and Contracts ReviewerScribd AccountNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Microsoft Office Word Document (3) DSFDokument2 SeitenNew Microsoft Office Word Document (3) DSFVikash Kumar ShuklaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law vs PowerDokument3 SeitenLaw vs PowerLusita LgNoch keine Bewertungen

- 15 Salient Features of The ConstitutionDokument3 Seiten15 Salient Features of The Constitutionjohn ryan100% (1)

- TX Commission On Law Enforcement - Training and Education Records For STEPHANIE BRANCH, DART PoliceDokument6 SeitenTX Commission On Law Enforcement - Training and Education Records For STEPHANIE BRANCH, DART PoliceAvi S. AdelmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights - SummaryDokument8 SeitenUniversal Declaration of Human Rights - SummaryAlena Icao-AnotadoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marcela Rodriguez-Farrelly-EngDokument33 SeitenMarcela Rodriguez-Farrelly-EngВікторія ПроданNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filipino GrievancesDokument1 SeiteFilipino GrievancesemanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Full (All Chapters Notes)Dokument100 SeitenFull (All Chapters Notes)Freester KingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court Denies Land Title RegistrationDokument2 SeitenCourt Denies Land Title Registrationarden1imNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ugbs 105 Introduction To Public Administration of Education School of ContinuingDokument18 SeitenUgbs 105 Introduction To Public Administration of Education School of ContinuingmaxiluuvNoch keine Bewertungen

- APU-Account Update FormDokument2 SeitenAPU-Account Update FormMichel FRANCOISNoch keine Bewertungen

- Void Agreements-1Dokument3 SeitenVoid Agreements-1Shreya SrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen