Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Coalition of The Willing. Or: Can Sovereignty Be Shared?

Hochgeladen von

Enis Latić0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

104 Ansichten22 SeitenThe paper argues that what Kant suggests as a surrogate is not shared sovereignty. It is really a false start to conceive of such an order as 'a legal order of legal orders,' says Berns. The coalition of the willing states is not a full-blown world republic, he says.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

View Pic

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe paper argues that what Kant suggests as a surrogate is not shared sovereignty. It is really a false start to conceive of such an order as 'a legal order of legal orders,' says Berns. The coalition of the willing states is not a full-blown world republic, he says.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

104 Ansichten22 SeitenThe Coalition of The Willing. Or: Can Sovereignty Be Shared?

Hochgeladen von

Enis LatićThe paper argues that what Kant suggests as a surrogate is not shared sovereignty. It is really a false start to conceive of such an order as 'a legal order of legal orders,' says Berns. The coalition of the willing states is not a full-blown world republic, he says.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 22

ABSTRACT.

Can Kant conceive of a legal order established between legal

orders? By introducing the coalition of the willing states as a surrogate for

a full-blown world republic, he surely claims he can. After a brief rehearsal of

Kants argument, the paper turns to a critical examination of its most principled

argument: as republican states are polities that have already left behind the state

of nature, they cannot be required to do so once more. By focusing on a con-

temporary understanding of surrogate sovereignty as shared sovereignty, this

paper argues that shared sovereignty presupposes classical unified sovereignty;

that what Kant suggests as a surrogate is not shared sovereignty; and that, there-

fore, either Kants idea does not help much, or it is in need of serious re-inter-

pretation. The remainder of the paper only suggests the beginnings of this re-

interpretation. In the case of an international legal order, we see representation-

al processes of anticipation and retrospection at work. If one takes these tempo-

ral cross-overs into account, it is really a false start to conceive of such an order

as a legal order of legal orders. Since various domestic legal orders acknowledge

the encompassing legal order as the legal order common between them, they do

not give up sovereignty when they decide to comply with the international legal

order. They exercise it, but in a new mix of constituent and constitutional power.

KEYWORDS. Kant, perpetual peace, sovereignty, international law, legal

pluralism, constituent power

T

owards the end of his essay on the rule of law in the process of

European integration, Berns suggests that Europe should not return

to the old conception of sovereignty and its lures, neither by replicating

the national state on a bigger canvas, nor by dissolving the national states

in their present multifarious forms. Instead, Europe must learn to share

sovereignty in a political order that demands perpetual peace and does not

fear surrogate.

1

The surrogate, as one will appreciate, refers to Kants

proposal for perpetual peace. I will briefly rehearse in what sense it should

The Coalition of the Willing.

Or: Can Sovereignty be Shared?

Bert van Roermund

Tilburg University

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES: JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN ETHICS NETWORK 12, no. 4 (2005): 443-464.

Doi: 10.2143/EP.12.4.2004792 2005 by European Centre for Ethics, K.U.Leuven. All rights reserved.

be called a surrogate. At this stage I will join the camp of Berns and oth-

ers in the hypothesis that the Kantian proposal is not so much a second

best solution to the problem of perpetual peace, as it is the only rational

option. Basically, the idea is that sovereignty in a global polity should be

exercised jointly. The main part of the paper, however, will consist of an

investigation into what exactly the suggestion of sharing sovereignty

amounts to. For although Berns suggests that this is what the surrogate

should aim at, on second thought the idea seems replete with paradoxes.

In the last part of the paper, I argue an alternative account of what can be

shared in exercising sovereignty.

1. REHEARSING KANTS SURROGATE

In the first Definitive Article of the essay On Perpetual Peace, Kant lays

down that the constitution of a state should be republican, i.e. loosely

what we call a democracy under the rule of law.

2

The theory is largely

identical to Rousseaus: the social contract establishes the principle that

allows for the exercise of power in the name of the law. The problem he

embarks on in the second Definitive Article pertains to the relationships

between such states or legal orders. Can these be captured, once more,

under the rule of law, now that the terms of these relations (the states

themselves) are already conceived of as governed by the rule of law? We

may reconstruct the problem by means of the following three statements

or conditions:

(1) If legal orders P, Q, R are parts of an encompassing legal order L,

they are not full-blown, sovereign states.

(2) If P, Q, R are sovereign states, there can be no encompassing L,

exercising sovereignty over them.

(3) Sovereignty, conceived of as supreme legal power, is a necessary

attribute of every legal order.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

444

The problem is a familiar one: How to conceive of a legal order of legal

orders? Some decades earlier than Kant, on the other side of the Rhine

River, Rousseau famously burnt his Institutions politiques, because he

realised that his theory (the social contract as the birth of sovereignty)

would never provide a solution to this problem. The social contract may

be a model for a legal order, but not for a legal order of legal orders. By

definition, it cannot be an iterative concept.

Kant acknowledges that the only coherent conception of a full-blown

international legal order on the basis of the social contract would be a

world republic (a Vlkerstaat), where member states would have trans-

ferred sovereignty, or at least certain rights of sovereignty, to an encom-

passing legal order L. The citizens of the former states would become, to

a certain extent, citizens of L, and the rules of L would have direct effect

on these citizens as legal subjects. On this account, the social contract is

expanded, not re-iterated. To put it in another way: we are well advised to

drop condition (2). But then Kant realises that there are some powerful

reasons for not dropping condition (2). Let me rehearse these reasons,

wrapping up the line of the arguments without following the lines of the

text.

The most principled one is, without doubt, that you cannot expect

states, i.e. sovereign legal orders, to comply with the maxim exuendi a statu

naturale, as one can expect human agents in the state of nature to do.

Giving up the state of nature is precisely what the constitution of a state

amounts to. You cannot, conceptually speaking, expect states to leave the

state of nature they already left by becoming states in the first place.

Building on this most basic objection against the world republic, Kant

adds others, in an effort to steer away from the magnetic pole of the

world republic and find a safe harbour for the idea of a legal order of legal

orders.

3

The first is that it is superfluous for republican states to make a

higher-level contract that would govern their mutual relationships under

unconditional peace. Republics have abolished violence as a means of

internal politics, unless their principles are in clear and present danger, the

445

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

reason being that they are committed to the principle that no agent, not

even a governmental agent, should be the judge in his own cause. This is

what lies at the heart of the idea of the rule of law. So why would they

suddenly forget the principle on which they are based when it comes to

external relations?

The argument seems to be fallacious, at least in its received reading.

Towards the end of this paper, however, I will acknowledge that it may

be powerful after all in a much more complex reading. For now, the

point is that the distinction between internal and external relations in

politics is to be made, by necessity, from the internal vantage point.

There is a preference in the difference here, as Waldenfels would say.

4

This preference entails that the principle nobody should be judge in his

own cause is always seen from the internal point of view; it governs a

polity already constituted by self-inclusion. Or, in a more political vein,

democracy under the rule of law is a system that commits members to

negotiate their common interest, i.e. the common interests of those who

they see as (future) members. These interests may precisely require them

to ignore the rule of law in external relations and go to war, as neo-colo-

nialism and wars for oil prove. It is not enough for two democracies in

conflict to acknowledge that they should not be judges in their own

causes; what they need to acknowledge is the authority of a third per-

son, a judge, to make a decision between them. But acknowledging this

authority would already amount to acknowledging an encompassing

legal order, which contradicts the thesis that it is superfluous for democ-

racies to step up to that higher level. Therefore, that democracies have

no reason to go to war unless out of self-defence, seems to be false on

conceptual grounds, quite apart from the overwhelming empirical

evidence of the contrary.

The remaining arguments ventured by Kant become weaker and

weaker, even to the point where they tend to become contradictory. In my

view, there is a considerable tension, for instance, between what could be

called his two arguments from antagonism. On the one hand, Kant fears

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

446

that the world republic will smother all competition and struggle, which is

the driving force in making things better. The world republic would bring

boring uniformity and uncritical mass behaviour to society: too little

antagonism. On the other hand, he also fears too much antagonism

between the various peoples brought together under a formal umbrella

that does not really unite them. Sooner or later, the world government will

recur to despotic rulings in order to contain heterogeneity within limits,

thus evoking resistance, more despotism, more resistance, etc., in a vio-

lent race to the bottom. Thus the world republic would bring the oppo-

site of unity.

But not only is there tension between these arguments. Neither of

them is particularly strong in itself, in view of Kants initial problem of

how to warrant unconditional peace between peoples. As to the former,

competition was not at issue, nor were all the possible forms of struggle;

the issue was a specific form of antagonism: war. If Kant would have con-

sented to the Heracleitean view that war is the father of all things, he

would not have written a proposal for perpetual peace. As to the latter,

then, the argument is a classical one against monarchical government: he

who can protect everything can destroy everything. But note that this

argument, if it would be valid, would apply to every singular legal order

and not specifically to a legal order of legal orders. Here again, if Kant

would have accepted this argument, he would not have embarked on the

First Definitive Article.

The weakest argument, in my view, is the one from Friendly

Commerce. Remember that Kant is aware that the model of a pactum

pacis will not work. What can be ended by the latter is not war but rather

a war: one can decide to end the war one is in the process of waging,

rather than decide to ban war altogether as an option to enforce what

the state sees as its right. Note, however, that this argument also applies

to what Kant otherwise seems to welcome as a major factor in world

peace: le doux commerce. As Hobbes already saw, the war of all against all

is not permanent war as the opposite of perpetual peace; it rather

447

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

pictures the conditionality of war over and against the unconditionality

of peace. So the peace of le doux commerce may well rest on a pactum pacis

as the decision not to wage a particular war rather than on a pact to

abolish war altogether which is not the problem Kant wishes us to

acknowledge.

So Kant does not fare too well in his efforts to keep premise (1) at

bay. On balance, the most principled line of his defence is the best one:

you cannot expect states to leave the state of nature they have already

left. Therefore, the only reasonable basis for a global legal order,

according to Kant, is what he calls a foedus pacificum in contradistinction

to a pactum pacis: a league for peace that can be joined, rather than a pact

for peace that should be complied with. What one acknowledges, he

believes, in joining this coalition is the preservation and corroboration

of the freedom of a state, both its own freedom and the freedom of the

allied states, rather than their subjection to higher laws or to authority

based on such laws. At this point of the argument, Kant adds his

famous note on the realisation of what he calls free federalism that

should lead to world peace: For if by good fortune one powerful and

enlightened nation can form a republic (which is by its nature inclined

to seek perpetual peace), this will provide a focal point for federal asso-

ciation among other states. These will join up with the first one, thus

securing the freedom of each state in accordance with the idea of inter-

national right, and the whole will gradually spread further and further

by a series of alliances of this kind.

5

After this passage, his main worry

is to keep the world state at bay as the necessary conceptual sequel of

such a federative union. He points out that this coalition or Bund of the

willing is the only construction to be relied upon if reason is to make

sense of the law of peoples at all, conceding (a) that this is a surrogate

for what would be the only coherent conception of a full-blown inter-

national legal order, to wit a world republic, and (b) that this coalition

will be permanently jeopardised by the unwilling, i.e. the ones that opt

out.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

448

2. LEAVING THE STATE OF NATURE TWICE?

The problem is to conceptualise founding and warranting unconditional

international peace, which is just another word for law. It is to conceptu-

alise international peace in as far as peace cannot be but founded. Kant had

argued as much at the beginning of the 2

nd

Abschnitt, introducing the two

definitive articles: peace is not a natural state (rather war is), so it must be

established, set, enacted, or posited. In this sense, the predicate positive

is analytically bound up with the concept of law. Whatever we may mean

by founding a legal order, it must entail the exercise of constituent

power, which is what this predicate positive points to in the final analy-

sis. Can the Kantian surrogate be conceived of as a form of founding

constituent power, and, if so, in what sense? On the one hand Kant is

stuck since he himself has conceded that such a coalition for peace will

not come about as a natural state of affairs, and needs to be established

by sovereign power. On the other hand he is stuck because he cannot

conceive of sovereign power established between states as power they

ought to obey. This is why Kant has to count on luck and a coalition of the

willing. But is this enough, conceptually speaking, to warrant founding

constitutive power that will somehow relate the plurality of legal orders to

the rule of one law?

Let us look once more at Kants most principled objection against

conceiving this coalition as a world state based on a contract between

states, by which they would consent to give up what we would call their

sovereignty. The objection was that, as republican states are polities that

have already left behind the state of nature, they cannot be required to do

so once more. At least three problems can be raised here.

1) Leaving the state of nature is an injunction that is incomprehensi-

ble, at least in some readings. Paradoxically, the state of nature has to

endure in order for the citizens to leave it, and this in two ways. Firstly,

that states are orders in which the state of nature is left behind is some-

thing that applies only internally, not externally. But, as already said, the

449

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

very distinction between internal and external is made from one of its

poles: the internal one. This preference can only be posited, set, or estab-

lished, if what is excluded by self-enclosure keeps hanging around as

beyond the border. So, in a sense, states do not leave the state of nature

behind: on the contrary, they originate in protracting the state of nature

that they are supposed to have abandoned, precisely as what is left behind.

Therefore, they cannot leave it behind. Secondly, even internally, the civil

state is not the negative counterpart of the state of nature. On the con-

trary, in as far as the state of nature mobilises the sphere of private inter-

ests, it is constitutive of the civil state in a positive way. Rousseau already

conceded as much in a remarkable footnote

6

on the general interest: the

general interest can only be articulated as a relationship between private

interests, which, by necessity, have to be expressed and heard in the civil

state as conflicting interests. Kants well-known analysis of human acting

as based on subjective drives leads to no other conclusion. Indeed, the

state of nature should not be left behind. The maxim exeundum a statu natu-

rali is a counterfactual norm in the strong sense: we should try, but we

should not realise it, as it would destroy the general interest as a relation

between private interests.

7

2) The second objection is that if Kants reasoning with regard to the

social contract is valid for individuals, it must also be valid for states, and

vice versa: if we allow Kants argument to apply to the relationship between

states, it will backfire on the relationships between individuals within a

state. The whole point of the social contract argument is that autonomous

agents, whether they are sovereign states or free individuals, will remain

autonomous or free in a higher sense if and when they turn to some form

of reciprocal recognition of private interests, and thus to common recog-

nition of reciprocity as a general interest. If individual agents can preserve

their freedom in making a contract, then collective agents can; if the

latter cannot, the former cannot either. What you cannot require, concep-

tually, is that the same agents, for instance individuals, do it twice. They

cannot give up the state of nature twice. But surely one contract can build

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

450

upon another in the sense that the legal subject formed by individuals

leaving the state of nature can itself leave the state of nature in turn in a

coalition with other such subjects.

3) The third objection would be that Kant comes too late, as he has

already given away his position. For the insight that republican states can-

not, conceptually speaking, lawfully interfere with each others business

and remain sovereign at the same time, makes sense only in view of a nor-

mative counterpart: a judge who speaks in the name of a higher legal

order. For the only sensible reading of cannot is ought not, and this

amounts to taking the legal point of view already. Therefore it concedes

that such normative legal order should be founded, enacted and enforced.

So I would be inclined to regard the allegedly principled argument that the

state of nature cannot be left twice as flawed. In one sense it can easily be

left twice, because the agents are different, in another sense it is impossi-

ble to leave it even once, because it is the essential though dangerous sup-

plement (to use a famous Derridean phrase) of the rule of law. But note

that this conclusion does not reject Kants argument entirely. Although it

rejects the argument that national states already contain enough warrants

for international peace, it also leaves room for an argument to the effect

that we should not prepare for a world state. But what argument would

that be? Here is where the model of shared sovereignty presents itself as

a feasible interpretation of what Kant had in mind, or should have had in

mind.

3. SURROGATE SOVEREIGNTY AND SHARED SOVEREIGNTY

Should we regard surrogate sovereignty as shared sovereignty? This is

what Berns does, and he is not the only one around. He is joined by, for

instance, Sir Neil MacCormick, who is as convinced as Berns is that the

European Community (or the Union, for optimists) makes a good case

451

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

for shared sovereignty.

8

Now I do not want to question, not primarily at

least, whether Europe makes a good case for the surrogate of a legal

order that Kant had in mind. In fact I think it does, but my reasons do

not hinge on the idea of reciprocity inherent in shared sovereignty.

Let me take issue with the crux of Bernss thesis by arguing in the follow-

ing way.

1) Shared sovereignty presupposes good old sovereignty.

2) What Kant suggests as a surrogate is not shared sovereignty.

3) So either Kants idea does not help much, or it is in need of serious re-

interpretation, of which I can only suggest the beginnings within the

framework of this paper.

9

3.1 Shared sovereignty old sovereignty

Elsewhere (Roermund, 2003), I have tried to make sense of shared sover-

eignty by using Michael Bratmans analysis of shared intentional action.

According to Bratman (1999), actors may be involved in shared intention-

al activity not only if they are doing the same thing (intentionally), but also

if they mesh sub-plans and are committed to mutual response and sup-

port in doing so, notwithstanding their distinct reasons, goals, and strate-

gies. For instance, you and I are taking a walk together, not if we take

the same walk, but if we also, for instance, coordinate our starting time,

the variations of our pace (you need a work-out, while I hate excercise),

the way we talk to each other, and so on. Thus, shared intentional activi-

ty is not identical to shared intentional cooperative activity. Shared inten-

tional action may well consist of sharp competition, for instance when

you and I turn our walk into a race. Also, agents involved in it may give

radically different accounts of their unity or jointness, though they will

not contest the attribution of unity to their enterprise as such.

10

This

clearly applies to the EC, where Member States often have their own

agendas in giving form to an acquis communautaire. But note that this is, in

essence, the model of the social contract all over again. And here we must

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

452

doubt, as Rousseau did,

11

if the social contract can found sovereignty? By

the social contract, one cannot establish who are to be parties to the con-

tract. This is a decision that is necessarily prior to the contract, and the

classical concept of sovereignty will reappear in any effort to account for

it. Obviously, this is the problem with any model expressing reciprocity

as the conceptual basis of the legal order, whether we call it contract,

dialogue, polyphony, or even game. By stressing reciprocity in shared

intentional action, one has yet to establish, indeed to decide, who will be

involved as the terms in reciprocal relationships. In cases of self-enclos-

ing orderings, the ordering always seems to precede the order, the saying

seems always prior to the said, as the setting always precedes the set, and

the founding the founded.

12

This is the reason why old sovereignty

returns at the heart of new sovereignty, as a moment of initial decision

making that cannot be shared. It remains initial, in that it initiates the

polis, time and again, by seizing the initiative. The obvious example is the

issue of enlarging the European Union: the decision where to stop enlarg-

ing the Union is a decision that cannot be made on grounds shared by the

candidate(s).

This is the cause of many a problematic phrase lingering on in the

various definitions of the notion of sovereignty, e.g. the famous

Bodinian predicate of the sovereign as legibus solutus; or the Austinian

definition that the sovereign is he who is habitually obeyed by others

while he is not in the habit of obeying others himself; or first and fore-

most the Schmittian phrase (Schmitt 1934, 14) that the sovereign is

both inside and outside the legal order.

13

It is this last phrase, in partic-

ular, that triggered critical reflections on sovereignty by Foucault,

Agamben, and Negri.

14

Analytically minded philosophers meet similar

conceptual puzzles. I refer to Colemans problems with Harts rule of

recognition

15

or Walkers discussions of constitutional pluralism in the

key of late sovereignty.

16

It is also the reason why less incisive legal

theorists in our time reject the whole notion of sovereignty as not only

utterly obsolete but also dangerously self-contradictory.

17

They argue

453

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

that it should be traded for democracy and human rights, only to find

themselves trapped in their replies to questions like who is to defend

democracy? Who is to grant and warrant human rights? Indeed, no

sooner have we sought refuge in reciprocal models of the polity, or

sovereignty awaits us right there, at the heart of reciprocity.

18

In the final

analysis, it seems, sovereignty cannot be shared, as the exercise of

sovereignty is already presupposed in determining between whom it is

to be shared.

3.2 Kants surrogate

Why should we be hesitant to interpret Kants surrogate as pointing to

shared sovereignty? Remember the picture: Kant makes the realisation

of world federalism the surrogate of a world republic - contingent on

good fortune: if good fortune would have it that a powerful and

enlightened people would transform itself into a republic, it could

become the centre of free federative association by other states on a glob-

al scale, which then would gradually grow to a coalition of the willing.

What strikes me in this picture is the emphasis on the first move, which

is unilateral and non-reciprocal. The ensuing process Kant hopes for is

one of aggregation rather negotiation.

There are two readings of this picture of aggregation that I would like

to reject out of hand. The first reading is this: a powerful and enlightened

nation transforms itself into a republic, and then invites others to join it

on conditions set by this grand nation. If this is what Kant had in mind,

his is a plea for imperialism. Not that his plea would not meet with

applause. On the contrary, many a story on the human condition boils

down to it; for instance the worn-out Fukuyama-story of the end of his-

tory, or Hffes idea of global justice.

19

Every polity (why should we hide

behind the word culture?) that presents itself as integrating all other poli-

ties poses as a superior, indeed, supreme power in the classical sense.

It clearly reinforces sovereignty rather than pre-empting it.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

454

The second picture comes closer to what I have in mind, although

it does not seem acceptable either. It is not so much the picture of a

great polity commanding or inviting the others, as it is a picture of the

great and therefore visible polity starting and other polities mimicking.

It is a picture not of following a leader (as the leader is not yet leader),

but of freely acknowledging a pattern of behaviour as paradigmatic.

One could say that Kant counts on luck in mimesis. Then, however, I

venture that the picture boils down to this: if states cannot share an

overriding legal order as theirs, they can at least accept the same legal

commitments as part of their respective legal orders. In other words,

Kant cuts out the reflexive element from the encompassing legal order

as a common enterprise. All states can do the same, although they

cannot do it together. This interpretation, however, would run into no

less great difficulties. It entails, I submit, that there can be no acquis com-

munautaire between these legal orders. For acquis communautaire already

entails the vantage point of a first person plural: the self of a polity.

Not only does this run counter to what matters most in practice, for

instance in the development of European Union Law and WTO law.

But also, on the conceptual level, it leads to an utterly dualist and, in

the final analysis, untenable view of international law. As Kelsen notes,

in this view international law is forced to undergo a complete denatur-

ing in the notion that it is incorporated into the legal system of ones

own state. For within the confines of a state legal system, international

law can no longer perform its essential function of coordinating, of

equally ordering, all states. () The validity of international law can be

abrogated, then, according to the rules of this constitution [i.e. of the

state adopting international law, BvR] in the most extreme case, by

way of a constitutional amendment.

20

So how can we say that the EU

is a good model of the Kantian surrogate, if this surrogate cuts out

what is most central to the EU: acquis communautaire, i.e. sharing as a

form of collective reflexivity, or in more abstract terms, a collective

self?

455

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

3.3 An alternative account

My own reading of Kants proposal, guided throughout by the non-recip-

rocal character of the first move, focuses on what it means for a polity

to transform itself into a republic. At the beginning of this paper, I loose-

ly paraphrased this in modern terms as becoming a democracy under the

rule of law. But what this means in philosophical terms is precisely what

is at stake in this paper. Up to now, the only philosophical account

I offered was that this transformation, like all political acting, builds on

self-enclosure, thus reiterating the internal point of view. More can and

should be said. Firstly, I see no argument to rebut the well-known claim

made by Claude Lefort, to the effect that political self-enclosure necessar-

ily entails reference to a realm beyond the would-be polity, transcending

a society in the sense that it is staged as the ultimate source of legitimate

power over this society.

21

As Lindahl (1997 and 1998) has stressed, this

permanence of political theology entails that the exercise of political

power is governed by a specific logic of representation: sovereign power

is always supreme but one. That is to say, it can only be power over law

if it poses as power by law, and it can only appear to be constituent power

if it presents itself as constituted power: deriving, that is, from the really

constituent power that transcends society. Sovereignty, therefore, is

bound up with the symbolic representation of a vertical dimension of the

polity. Secondly, however strong this claim is, there is another one made

by Hannah Arendt that should somehow be reconciled with Leforts.

22

Political thought, says Arendt, is representative. I form an opinion by

considering a given issue from different viewpoints, by making present to

my mind the standpoints of those who are absent; that is, I represent

them. This process of representation does not blindly adopt the actual

views of those who stand somewhere else, and hence look upon the world

from a different perspective; this is a question neither of empathy, as

though I tried to be or feel like somebody else, nor of counting noses and

joining a majority but of being and thinking in my own identity where

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

456

actually I am not (Arendt 1980 [1961], 241). Arendts argument typically

revolves around the first person singular. But this is immaterial; it is easy

to see why the polity as a first person plural, in its relation to other poli-

ties, is in the background. For Arendt, the others in this context are the

ones who are absent, i.e. who do not register as those involved in the poli-

ty. They are the ones who are sacrificed in order to constitute a public

space, a common wealth, and a collective identity. So Arendt claims that

political representation is dependent, not only on a vertical dimension

transcending society, but also on a horizontal dimension, in the sense that

it is mindful of its origin in inclusion / exclusion. Such political mindful-

ness precedes moral judgement. Thus, if we say with Lefort that a polity

constitutes itself from the outside as the polity in virtue of a vertical

dimension, as if it were the only one existing, we should also appreciate,

with Arendt, that a polity can only constitute itself from the outside if, in

virtue of its horizontal dimension, it is obliquely aware of its being one

among many, its members not registering in other polities, similar yet dif-

ferent. Politics is rooted in the fact that men are plural, states Arendt in

the first Fragment on the question What is politics?; and she continues:

Politics is about the being together and the mutual presence of those

who differ.

23

This pertains not only to individuals; polities are plural, too,

precisely in the way they set the stage for representing their foundation.

By consequence, representation of the thinking of the others, rooted as

it may be in the polity as a bounded whole, cannot evade the lateral aware-

ness of not registering in other polities itself. Precisely in order to success-

fully enclose itself, the polity has to take into account that it itself exclud-

ed; i.e. that it is not only the subject, but also the object of exclusion.

This enlarged mode of thinking is the core of Arendts famous read-

ing of the Critique of Judgment as a treatise in political philosophy.

24

It comes quite close, I believe, to a politico-legal reading of what Gadamer

defined as openness in judging: to let something count against yourself

by yourself, i.e. even though no one forces you to do so.

25

This definition

has a clear political relevance: a body politic that is open in this sense,

457

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

that is to say, a body politic that makes something count against its own

self-enclosure in its self-enclosure, even if no one else coerces it do so,

such a polity transforms itself into a republic, to return to our Kantian

core phrase. And if it finds credible institutional forms to represent this

basic, founding gesture, we call it a Rechtsstaat.

Three observations are to be made here. Note, firstly, that this trans-

formation is not based on reciprocity. It is a sort of unilateral self-restraint

in the representational discourse of a polity, by which it recognises that it

should not define its environment exhaustively as a function of its identi-

ty, how ever strongly it is inclined to do so, if it were to follow the logic

of political representation. Therefore, such recognition is not a strategic,

instrumental, or functional one. It is not based, as Luhmann, for instance,

would have it, on trade-offs between cognitive openness and functional

closure. Note also, secondly, that it does not contradict Leforts thesis on

politics as based on self-enclosure. On the contrary, it can be heard only

as an overtone in the dominant chant of the polity, which is based,

throughout, on staging reference to a transcendent source of legitimate

power, and a corresponding articulation of collective identity. To mention

the most obvious example: the reason why democracy accords with the

rule of law is not that majority rules, but that it rules on condition that it

warrants a minority the institutionally embedded chance to become a

majority. Thirdly, what counts against the self-enclosure of a polity is

dependent on how it articulates its identity. If it worships a god, respect

for a non-religious life is a way of recognising what counts against it.

It may be institutionalised by the separation of church and the state. If it

sees itself as a free market society, anticipating the destructive effects of

market failures is a way of recognising what counts against it. It may be

institutionalised by monitors of fair competition.

The enlarged mode of political thinking proposed by Kant governs the

structure of constituent power. Its unilateral character leaves no room for

sharing. Yet, the very same model allows us to assign a place to shared

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

458

exercise of sovereign power. To see how and why, remember the double

bind of sovereignty as both constituent and constitutional power. We saw

that constituent power must pose as exercising constitutional power, i.e.

already established and conferred power, in order to be credible from an

action perspective. It is only in retrospect that it can be acknowledged as

constituent. Only if it turns out to have been felicitous in hindsight we call

a revolution a revolution. At the time of its outburst, it is revolt, resist-

ance, or terrorism against the coalition of the willing. In a similar way,

sovereign power as constituent power is only outside the legal order in

hindsight, never at the moment it is exercised. At the time of action,

it anticipates a future polis that has always been a past.

Therefore, Schmitt (in the Agambenian reading) was wrong: the sov-

ereign is never inside and outside the legal order at the same time.

26

At the time of action, the would-be sovereign body has to act as if it were

inside the legal order, i.e. as if it obeyed established law. Established law

is not black letter law. Its rules are admittedly always open to interpreta-

tion and change. Interpretation and change become of course critical

under certain pressing circumstances, and I have no objection to the def-

inition of the sovereign as the agent who decides whether these condi-

tions obtain and what is to be done. But even under such circumstances

supreme power has to pretend to be bound by law, although it can appear

to have gone beyond it in retrospect.

27

Indeed the legal order establishes

supreme authority precisely with a view to taking decisions when things

grow tough.

Where does this leave us with regard to constituting the supra-nation-

al legal order? In the case of an international legal order, we see similar

representational processes of anticipation and retrospection at work.

If one takes these temporal cross-overs into account, it is really a false

start to conceive of such an order as a legal order of legal orders. The

sheer fact that the various domestic legal orders come to acknowledge the

encompassing legal order as the legal order common between them indi-

cates that they do not give up sovereignty when they decide to comply

459

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

with the international legal order. They exercise it, but in a new mix of

constituent and constitutional power. The four freedoms in Europe are a

case in point: they can only remain the basis of the Community if the

Member States will continue to grant them each other. But this presuppos-

es precisely that the competence to grant them remains fully vested with

the Member States. The doctrine of direct effect in EC law is a logical

consequence of this; it forces states to see themselves primarily as mem-

bers in the sense of organs rather than parts.

28

If it is true that constituent power is acknowledged in retrospect, so

that it has to anticipate the future in order to pose as constitutional power

in the present, it is by no means indifferent which institutions of consti-

tutional power are made available. Like in art or in science, also in politics

some institutions are more suited to support (what later appears to have

been) creativity and innovation than others. We are inclined to believe

but this is an empirical law with remarkable exceptions that institutions

with a self-critical climate of exchange, communication, and evaluation do

better in sustaining great talent, new ideas, and smart strategies than insti-

tutions driven by top-down command, rigid programmes and no feed-

back. By virtue of their flexibility, these participatory institutions will eas-

ier accommodate the potentiality of singular initiatives that open up new

perspectives. In the realm of international constitutional law, to take part

in such institutions may well make the impression of exercising shared

sovereignty; until we realise that it is constitutional, not constituent

power that can be shared.

29

REFERENCES

Agamben, G. (1998). Homo sacer. Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Transl. by D. Heller-

Roazen, Stanford, Stanford University Press.

Arendt, H. (1980 [1961]). Between Past and Future. Eight Exercises in Political Thought.

Harmondsworth etc., Penguin Books.

Arendt, H. (1992 [1982]). Lectures on Kants Political Philosophy. ed. with an interpretive

essay by Ronald Beiner. Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

460

Arendt, H. (2003 [1993]). Was ist Politik? Fragmente aus dem Nachlass. Hrsg. U. Ludz,

Vorwort K. Sontheimer. Mnchen - Zrich, Piper.

Berns, E. (2003a). European Surrogate. The Cultural Diversity of European Unity. W. Arts,

J. Hagenaars and L. Halman. Leiden - Boston, Brill: 449-462.

Berns, E. (2003b). O trouver un schme mdiateur entre lhospitalit et la politique des

tats modernes? Derrida. M. Mallet and G. Michaud. Paris, ditions de lHerne:

232-239.

Bratman, M. E. (1999). Faces of Intention. Selected Essays on Intention and Agency. Cambridge,

Cambridge University Press.

Coleman, J. (2001). The Practice of Principle. In Defense of a Pragmatist Approach to Legal Theory.

Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Foucault, M. (1988). Power/Knowledge. Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. Ed.

by C. Gordon, New York, Pantheon Books.

Gadamer, H.-G. (1975). Wahrheit und Methode. Grundzge einer philosophischen Hermeneutik.

3., erw. Aufl. Tbingen, Mohr.

Hardt, M. and A. Negri (2000). Empire. Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press.

Kelsen, H. (1992). Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory. A translation of the First

Edition of the Reine Rechtlehre or Pure Theory of Law, by Bonnie Litchewski

Paulson and Stanley L. Paulson, with an Introduction by Stanley L. Paulson.

Oxford, Clarendon Press.

Kelsen, H. (1994). Reine Rechtslehre. Einleitung in die rechtswissenschaftliche Problematik. 1.

Aufl., 2. Neudr. der 1. Aufl. Leipzig und Wien 1934 mit Vorwort zum Neudruck

von Stanley L. Paulson und Vorrede zum 2. Neudr. von Robert Walter. Aalen,

Scientia Verlag.

Kelsen, H. (1998). Sovereignty. S.L. Paulson and B. Litschewski Paulson (eds.), Normativity

and Norms. Critical Perspectives on Kelsenian Themes. Oxford: 525-536.

Lefort, C. (1986). Essais sur le politique (XIXe-XXe siecles). Paris, Du Seuil,.

Lindahl, H. (2002). Gadamer, Kelsen and the Limits of Legal Interpretation.

Phnomenologische Forschungen: 27-49.

Lindahl, H. (2003). Dialectic and Revolution. Confronting Kelsen and Gadamer on

Legal Interpretation. Cardozo Law Review 24(2): 769-798.

Lindahl, H. K. (1997). Sovereignty and Symbolization. Rechtstheorie 28: 347-371.

Lindahl, H. K. (1998). Democracy and the Symbolic Constitution of Society. Ratio Iuris,

11: 12-35.

Lindahl, H. K. (2001). Sovereignty and the Institutionalization of Normative Order.

Oxford Journal of Legal Studies 21: 165-180.

MacCormick, D. N. (2004). Questioning Post-Sovereignty (review article). European

Law Review 29: 852-863.

Mouffe, C. (2000). The Democratic Paradox. London, Verso.

Negri, A. (1992). Le pouvoir constituant. Essai sur les alternatives de la modernit. Trad. E. Balibar

et Fr. Matheron. Paris, PUF.

Roermund, B. v. (2003a). First-Person Plural Legislature: Political Reflexivity and

Representation. Philosophical Explorations 6(3): 235-250.

461

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

Roermund, B. v. (2003b). Sovereignty: Unpopular and popular. Sovereignty in Transition.

N. Walker. Oxford - Portland (Or), Hart Publishing: 33-54.

Roermund, G. v. (2000). Volksvertegenwoordiging. Rousseaus Maatschappelijk verdrag in de

spiegel van de rechtsstaat. Leende, Damon: 160 pp.

Rousseau, J.-J. (1762). Du contrat social ou principes du droit politique.

Schmitt, C. (1934). Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre von der Souvernitt. 2. Aufl.

(1. Aufl. 1922). Mnchen - Leipzig, Duncker & Humblot.

Vollrath, E. (1993). Hannah Arendts Kritik der politischen Urteilskraft. Die Zukunft

des Politischen. Ausblicke auf Hannah Arendt. P. Kemper. Frankfurt a.M., Fischer

Taschenbuch Verlag: 34-54.

Waldenfels, B. (1987). Ordnung im Zwielicht. Frankfurt a.M., Suhrkamp.

Waldenfels, B. (1994). Antwortregister. Frankfurt a. M., Suhrkamp.

Waldenfels, B. (1999). Vielstimmigkeit der Rede. Studien zur Phnomenologie des Fremden, 4.

Frankfurt a. M., Suhrkamp.

Waldenfels, B. (2001). Verfremdung der Moderne. Phnomenologische Grenzgnge. Gttingen,m

Wallstein Verlag.

Walker, N. (2001a). All Dressed Up. Oxford Journal Legal Studies 21(3): 563-582.

Walker, N. (2001b). Human Rights in a Postnational Order: Reconciling Political and

Constitutional Pluralism. Sceptical Essays on Human Rights. T. Campbell, K. D.

Ewing and A. Tomkins. Oxford, Oxford University Press: 119-141.

Walker, N. (2002). The Idea of Constitutional Pluralism. The Modern Law Review 65(3):

317-359.

Walker, N., Ed. (2003). Sovereignty in Transition. Oxford, Hart Publishing.

NOTES

1. Berns (2003), 461.

2. We, to be sure; not Kant. Cf. BA 24, the very last sentence, and BA 25 where democra-

cy in Kants sense is usually a disaster weil alles da Herr sein will.

3. Berns summarises them as quatre excellentes raisons (2003), though I wish to present them

here in a slightly different order. As will become clear, I find them less than excellent.

4. Waldenfels (1994), 202.

5. Denn wenn das Glck es so fgt: da ein mchtiges und aufgeklrtes Volk sich zu einer Republik (die

ihrer Natur nach zum ewigen Frieden geneigt sein mu) bilden kann, so gibt diese einen Mittelpunkt der fdera-

tiven Vereinigung anderer Staaten ab, um sich an sie anzuschlieen, und so den Freiheitszustand der Staaten,

gem der Idee des Vlkerrechts, zu sichern, und sich durch mehrere Verbindungen dieser Art nach und nach

immer weiter auszubreiten. The translation is from Immanuel Kant, Perpetual Peace:

A Philosophical Sketch, Kant: Political Writings, ed. H.S. Reiss, trans. H.B. Nisbet (Cambridge:

Cambridge UP, 2003 [1970]) 104.

6. Rousseau 1762, II, 3.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

462

7. In a similar vein, see Mouffe on reconciliation: a good that exists as a good only as long

as it cannot be reached, (2000), 137. I submit that this goes for all Habermasian counterfactual

presuppositions of critical discourse.

8. Cf. MacCormick (2004). See Lindahl (2001) for a critical review.

9. In other words, either Berns is right in understanding Kant, but then his account refers

us back to where we came from: sovereignty as a moment of sheer decision on who is to be count-

ed in the number of those who are going to share. Or Kant is up to something else: the decision,

by a great nation, to refrain from exercising power and take the risk of not being reciprocated. My

discussion with Berns is, I suppose, that reciprocity has to be founded as much as a legal order.

10. What does this mean in actual practice? It means that these actors will try to convince

their audiences of their respective accounts, but not at the costs of using force or leaving the poli-

ty in case they fail. As long as they can make a distinction between opting out and walking away,

the unity of the subject-agent retains a prima facie credibility. But they cannot make that distinc-

tion at will or make it a matter of unqualified negotiation without giving up their claims to repre-

sentation: some forms of opting out will be regarded as walking away. The fact that some mem-

ber states of the EU opted out with regard to the social or the monetary parts of the Treaty, was

a major contestation of what the European legal order was about in the eyes of the other member

states. So were the (much earlier) Solange decisions by the German Constitutional Court, when it

was decided that the rulings of the European Court of Justice would only have direct effect in the

BRD as long as its performance in protecting human rights would meet the standards set by the

German Grundgesetz (to be judged by the same German Court, to be sure). As long as these modes

of opting out do not meet with a veto from other parties to the Treaty, and as long as a veto from

other parties does not lead to going solo and leaving the Treaty, the format of ultimate unity is not

simply negated by contestation; rather it is reconfirmed by a form of contestation that does not

prompt its protagonists to radical practical implications. Radically contesting what would count as

the most acceptable account of the unity of the European legal order is, on the level of speech

acts, one way of radically confirming that such unity is what counts at the end of the day.

11. For my admittedly unorthodox Rousseau interpretation, see Roermund (2000).

12. I am indebted to Waldenfels here, in particular: Waldenfels (1987; 1994; 1999; 2001).

13. Agamben expressly interprets Schmitt as saying that the sovereign is inside and outside

the legal order at the same time, (1998), 15. Strictly speaking this is not what Schmitt says.

14. Foucault (1988); Negri (1992); Agamben (1998); Hardt and Negri (2000).

15. The rule of recognition, we are told, exists only when officials act in a certain way; but

whether or not individuals are officials in the relevant sense seems to depend on the existence of

a rule of recognition. After all, people are officials in virtue of the laws that create officials,

Coleman (2001), 100-101.

16. Walker (2001); Walker (2001); Walker (2002); Walker (2003).

17. For explicit counterarguments, see Roermund (2003).

18. And Bush abused this predicament when, in January 2003, he challenged the UN to take

its own resolutions (against the Saddam Hussein regime in Iraq) seriously or else the USA would

lead a coalition of the willing.

19. I owe Hans Lindahl for pointing this out, although perhaps he would opt for a different

interpretation. I quote from a manuscript Lindahl kindly shared with me, Appendix to

463

ROERMUNDTHE COALITION OF THE WILLING

Globalization and the Politics of Boundaries, which criticises Hffes Democracy in the Era of

Globalization. See p. 29 of this book: the global civilization begins in and spreads out from one

great region, the West.

20. Kelsen (1994), 143, quoted from Kelsen (1992), 116-117.

21. See Lefort (1986), in particular the essay Permanence du thologico-politique?.

22. I follow a line of thought argued by Vollrath (1993),which I think should be taken into

account by all supporters of Lefort. The link to Leforts thesis is mine.

23. Both quotations are from Arendt (2003 [1993]), 9. Viskers point, made elsewhere in this

volume, that one should realise that extreme differences do not register is well-taken.

24. In particular, she keeps referring to 40 of the Kritik der Urteilskraft; cf. Arendt (1992

[1982]), 71; cf. Truth and Politics, in Arendt (1980 [1961]), 241.

25. Cf. Gadamer (1975), 343: Offenheit fr den anderen schliet () die Anerkennung ein,

da ich in mir etwas gegen mich gelten lassen mu, auch wenn es keinen anderen gbe, der es

gegen mich geltend machte.

26. And Agamben is perhaps too generous in conceding him this point.

27. This is powerfully argued with regard to the ECJs role in the development of European

Union law by Hans Lindahl; cf. Lindahl (2001); Lindahl (2002); Lindahl (2003).

28. Here I think Kelsen was right. See Kelsen (1994), 150ff. See also Kelsen (1998), 529:

The so-called sovereignty of the state, then, is nothing other than its immediate relation to

international law.

29. I am grateful to Hans Lindahl for critical comments on an earlier draft. He does not

agree with my charitable Arendt interpretation. For him, Arendt remains under the spell of reci-

procity, so that my reference to her concept of the polity makes my argument self-contradictory.

I hope to argue in another paper in greater detail that there is a sense in which Arendts concept

of political self-inclusion entails an oblique awareness (permeating various forms of first person

plural reflexivity) that those who are excluded are still included, not only as excluded but also as

excluding. But of course this does not amount to reciprocal relationships.

ETHICAL PERSPECTIVES DECEMBER 2005

464

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Assignment - Reading The VeldtDokument2 SeitenAssignment - Reading The VeldtAbdullah Shahid100% (1)

- International Aviation Law Course OutlineDokument8 SeitenInternational Aviation Law Course OutlineEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Kantian Defense of Classical Liberalism GMUDokument33 SeitenA Kantian Defense of Classical Liberalism GMUmariabarreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- On The Potential and Limits of (Global) Justice Through Law. A Frame of Research. Gianluigi PalombellaDokument12 SeitenOn The Potential and Limits of (Global) Justice Through Law. A Frame of Research. Gianluigi Palombellaben zilethNoch keine Bewertungen

- From The Complaints of PovertyDokument11 SeitenFrom The Complaints of PovertyManuel Oro JaénNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mauro Cappelletti - Judicial Review in Comparative PerspectiveDokument38 SeitenMauro Cappelletti - Judicial Review in Comparative PerspectiveleyzalfdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational DevelopmentDokument12 SeitenOrganizational DevelopmentShara Tumambing MA PsyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Engleski Jezik Takmicenje VIII 8 LUKAVAC 2012Dokument8 SeitenEngleski Jezik Takmicenje VIII 8 LUKAVAC 2012Enis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 1: Rules and OrderVon EverandLaw, Legislation and Liberty, Volume 1: Rules and OrderBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (13)

- Constitutionalism and PluralismnewDokument34 SeitenConstitutionalism and PluralismnewvishalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Design Thinking For Business StrategyDokument30 SeitenDesign Thinking For Business Strategy2harsh4uNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jeremy Waldron. Kant's Legal Positivism PDFDokument33 SeitenJeremy Waldron. Kant's Legal Positivism PDFArthur Levy Brandão KullokNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kennedy, Duncan - Toward An Historical Understanding of Legal ConsciousnessDokument22 SeitenKennedy, Duncan - Toward An Historical Understanding of Legal ConsciousnessplainofjarsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kant Concept of International LawDokument29 SeitenKant Concept of International LawAnonymous 6mLZ4AM1NwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Louis Trolle Hjemslev: The Linguistic Circle of CopenhagenDokument2 SeitenLouis Trolle Hjemslev: The Linguistic Circle of CopenhagenAlexandre Mendes CorreaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBLM PALDC Basic Greetings and ExpressionDokument41 SeitenCBLM PALDC Basic Greetings and ExpressionJennifer G. Diones100% (4)

- AGOZINO, Biko. Counter-Colonial Criminology - OcredDokument149 SeitenAGOZINO, Biko. Counter-Colonial Criminology - OcredVinícius RomãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- On the Old Saw: That May be Right in Theory But It Won't Work in PracticeVon EverandOn the Old Saw: That May be Right in Theory But It Won't Work in PracticeBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical SketchDokument4 SeitenPerpetual Peace: A Philosophical SketchJoshua De Leon TuasonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Contract TheoryDokument23 SeitenSocial Contract TheoryJoni PurayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ant and Roperty Ights: Journal of Libertarian StudiesDokument22 SeitenAnt and Roperty Ights: Journal of Libertarian StudiesMadu BiruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kant, Rawls and Pogge On Global Justice: Th. Pogge, World Poverty and Human Rights, Polity Cambridge 2002Dokument19 SeitenKant, Rawls and Pogge On Global Justice: Th. Pogge, World Poverty and Human Rights, Polity Cambridge 2002Mihaela NițăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kant Rawls Pogge GJDokument18 SeitenKant Rawls Pogge GJMariaAlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kant Antirevolutionary StateLawObedience PDFDokument47 SeitenKant Antirevolutionary StateLawObedience PDFCarlos F GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constitutional Adjudication - Pasquale PasquinoDokument13 SeitenConstitutional Adjudication - Pasquale PasquinocrisforoniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy and Judicial Review in America.Dokument13 SeitenDemocracy and Judicial Review in America.PatrtickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Souverei Global WorldDokument14 SeitenSouverei Global WorldЕкатерина ЦегельникNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nobles, Richard Schiff, David - Civil Disobedience and Constituent PowerDokument19 SeitenNobles, Richard Schiff, David - Civil Disobedience and Constituent PowerRafaelBluskyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 Modern Law of NationsDokument254 Seiten4 Modern Law of Nationspamella640Noch keine Bewertungen

- Balibar, Etienne - Jus Pactum Lex On The Constitution of The Subject in The Theologico-Political TreatiseDokument18 SeitenBalibar, Etienne - Jus Pactum Lex On The Constitution of The Subject in The Theologico-Political Treatisezvonomir100% (1)

- Hoffman Penn DCCDokument24 SeitenHoffman Penn DCCAs RmNoch keine Bewertungen

- derechoUniversalDelmas PDFDokument25 SeitenderechoUniversalDelmas PDFDiego SanvicensNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Order: Constitution of The Order Being Formed Today. We Should RuleDokument19 SeitenWorld Order: Constitution of The Order Being Formed Today. We Should RuleDaniel ArizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Höffe, Otfried - Some Kantian Reflections On A World Republic (PP 51-71)Dokument22 SeitenHöffe, Otfried - Some Kantian Reflections On A World Republic (PP 51-71)Cesar Jeanpierre Castillo GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rechtsstaat Rule of Law Letat de DroitDokument30 SeitenRechtsstaat Rule of Law Letat de DroitMarta Di CarloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law and Sovereignty Draft PaperDokument35 SeitenLaw and Sovereignty Draft PaperSquall LeonhartNoch keine Bewertungen

- LIDO MENDES, Conrado Hübner - Is It All About The Last Word - Deliberative Separation of Powers 1Dokument42 SeitenLIDO MENDES, Conrado Hübner - Is It All About The Last Word - Deliberative Separation of Powers 1Anna Júlia PennisiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MENDES, Conrado Hubner. Neither Dialogue Nor Last Word - Deliberative Separation PDFDokument31 SeitenMENDES, Conrado Hubner. Neither Dialogue Nor Last Word - Deliberative Separation PDFLuiz Paulo DinizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deliberative Separation of Powers III - Conrado Hübner MendesDokument31 SeitenDeliberative Separation of Powers III - Conrado Hübner MendesDireito 2015.2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Theoretical Inquiries in LawDokument29 SeitenTheoretical Inquiries in LawsebahattinNoch keine Bewertungen

- KOSKENNIEMI 2007 Formalism, Fragmentation, Freedom. Kantian Themes in Today's International LawDokument22 SeitenKOSKENNIEMI 2007 Formalism, Fragmentation, Freedom. Kantian Themes in Today's International Lawd31280Noch keine Bewertungen

- 06 Wonicki PDFDokument10 Seiten06 Wonicki PDFUzeir AlispahicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Falsehoods Not Intended To Deceive - Popular Sovereignty and Higher LawDokument24 SeitenFalsehoods Not Intended To Deceive - Popular Sovereignty and Higher LawozgucoNoch keine Bewertungen

- EnlightenmentDokument3 SeitenEnlightenmentDeepak AanjnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- DODSON (Autonomy and Authority in Kant's Rechtslehre) PDFDokument20 SeitenDODSON (Autonomy and Authority in Kant's Rechtslehre) PDFAnonymous b8QjFqes9Noch keine Bewertungen

- (Hart Studies in Comparative Public Law) Alain Supiot - Governance by Numbers - The Making of A Legal Model of Allegiance-Hart Publishing (2017)Dokument309 Seiten(Hart Studies in Comparative Public Law) Alain Supiot - Governance by Numbers - The Making of A Legal Model of Allegiance-Hart Publishing (2017)Murillo van der LaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imperative Theory of The StateDokument23 SeitenImperative Theory of The StateParinita SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Pluralismul Juridic GriffithDokument44 Seiten2 Pluralismul Juridic GriffithFlorin UrdaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3.1 - Sypnowich, Christine - Consent, Self-Government and Obligation (En)Dokument22 Seiten3.1 - Sypnowich, Christine - Consent, Self-Government and Obligation (En)Johann Vessant RoigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Habermas Plea For A Constitutionalization of International LawDokument11 SeitenHabermas Plea For A Constitutionalization of International LawLiga da Justica Um Blog de Teoria PolíticaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penner 40to48Dokument9 SeitenPenner 40to48dhrupadmalpani2265Noch keine Bewertungen

- SSRN Id1272264Dokument78 SeitenSSRN Id1272264Bella_Electra1972Noch keine Bewertungen

- Separation of Powers and The Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent BodiesDokument11 SeitenSeparation of Powers and The Independence of Constitutional Courts and Equivalent BodiesinsaifulNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Politics of International Law - Martti KoskenniemiDokument29 SeitenThe Politics of International Law - Martti KoskenniemiCarlos Manuel EgañaNoch keine Bewertungen

- James 1999 SovereigntyDokument17 SeitenJames 1999 SovereigntyMariana MendívilNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Prospects For International Law: by Georg SchwarzenbergerDokument15 SeitenThe Prospects For International Law: by Georg SchwarzenbergerAlexandre GuerreiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principle of The Separation of Powers and The Constitutional Justice SystemDokument15 SeitenPrinciple of The Separation of Powers and The Constitutional Justice SystemShubham TanwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- IS LAW Just A Means TO AN End ?: Roger CotterrellDokument7 SeitenIS LAW Just A Means TO AN End ?: Roger CotterrellSuMan ŚahilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lacan at The Limits of Legal Theory-Steven MillerDokument14 SeitenLacan at The Limits of Legal Theory-Steven MillerOezlem EliasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elster ConstitutionsandConstitution-MakingDokument87 SeitenElster ConstitutionsandConstitution-MakingPerú Constituciones Siglo XixNoch keine Bewertungen

- Response Paper To Chapter 8-The Constitution of The StateDokument14 SeitenResponse Paper To Chapter 8-The Constitution of The StateUditanshu MisraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2 Defining State and SocietyDokument11 SeitenUnit 2 Defining State and SocietyMilisha ShresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PLJ Volume 39 Number 3 - 03 - Florentino P. Feliciano - On The Functions of Judicial ReviewDokument19 SeitenPLJ Volume 39 Number 3 - 03 - Florentino P. Feliciano - On The Functions of Judicial ReviewredcosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soul of JusticeDokument24 SeitenSoul of JusticeSandhya TMNoch keine Bewertungen

- Separation of PowersDokument11 SeitenSeparation of PowersAhmad Husaini Bin HussinNoch keine Bewertungen

- POSITIVISM INTRO and AUSTINDokument12 SeitenPOSITIVISM INTRO and AUSTINMomin KhurramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colonial ConstitutionalismDokument35 SeitenColonial ConstitutionalismShivani ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Not So Wild, Wild WestDokument21 SeitenThe Not So Wild, Wild WestEric Garris100% (1)

- Constitutionalism Meaning Development & Prospects of Constitutionalism BA-I DrtanujasinghDokument17 SeitenConstitutionalism Meaning Development & Prospects of Constitutionalism BA-I DrtanujasinghDhanraj KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plants in MotionDokument15 SeitenPlants in MotionEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slann 2011 Sovereignty and Jurisdiction in The Airspace and Outer SpaceDokument2 SeitenSlann 2011 Sovereignty and Jurisdiction in The Airspace and Outer SpaceEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- USCODE 2011 Title49 SubtitleVII PartA Subparti Chap401 Sec40103Dokument3 SeitenUSCODE 2011 Title49 SubtitleVII PartA Subparti Chap401 Sec40103Enis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- SandDokument19 SeitenSandEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Signal Leader's GuideDokument2 SeitenThe Signal Leader's GuideEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viruses: Higher Human BiologyDokument18 SeitenViruses: Higher Human BiologyEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afd 110929 023Dokument52 SeitenAfd 110929 023Enis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afi36 2101Dokument152 SeitenAfi36 2101Enis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Afi36 2101Dokument152 SeitenAfi36 2101Enis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pravo Na Slobodu I Sigurnost LicnostiDokument78 SeitenPravo Na Slobodu I Sigurnost LicnostiNedim SeferovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Right To MarryDokument31 SeitenA Right To MarryEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

- American M35 Army TruckDokument4 SeitenAmerican M35 Army TruckEnis LatićNoch keine Bewertungen

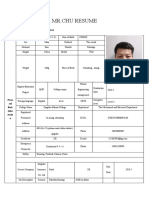

- Mr. Chu ResumeDokument3 SeitenMr. Chu Resume楚亚东Noch keine Bewertungen

- LiberalismDokument2 SeitenLiberalismMicah Kristine Villalobos100% (1)

- Statistics SyllabusDokument9 SeitenStatistics Syllabusapi-240639978Noch keine Bewertungen

- Paul Cairney - Politics & Public PolicyDokument5 SeitenPaul Cairney - Politics & Public PolicyCristiano GestalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forward Chaining and Backward Chaining in Ai: Inference EngineDokument18 SeitenForward Chaining and Backward Chaining in Ai: Inference EngineSanju ShreeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 18-My Soul To Take - Amy Sumida (244-322)Dokument79 Seiten18-My Soul To Take - Amy Sumida (244-322)marinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yusrina Nur Amalia - 15 U-068 - LP VHSDokument17 SeitenYusrina Nur Amalia - 15 U-068 - LP VHSYusrina Nur AmaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Volunteer Manual Catholic Community Services of Western WashingtonDokument42 SeitenVolunteer Manual Catholic Community Services of Western WashingtonmpriceatccusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Concept of HRMDokument9 SeitenBasic Concept of HRMarchanashri2748100% (1)

- PTO2 Reflection Rolando EspinozaDokument3 SeitenPTO2 Reflection Rolando Espinozaleonel gavilanesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filip CHICHEVALIEV REVIEW OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH LAW IN THE CONTEXT OF WHO POLICIES AND DIRECTIONSDokument15 SeitenFilip CHICHEVALIEV REVIEW OF THE PUBLIC HEALTH LAW IN THE CONTEXT OF WHO POLICIES AND DIRECTIONSCentre for Regional Policy Research and Cooperation StudiorumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media & Society SyllabusDokument4 SeitenMedia & Society SyllabusHayden CoombsNoch keine Bewertungen

- DMIT Sample ReportDokument33 SeitenDMIT Sample ReportgkreddiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resources Used in Abhidharmakośa-Bhā Ya: Biographical SourcesDokument2 SeitenResources Used in Abhidharmakośa-Bhā Ya: Biographical Sourcesdrago_rossoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 01 Doctoral Thesis Rainer LENZDokument304 Seiten2013 01 Doctoral Thesis Rainer LENZSunnyVermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Theology of SexualityDokument20 SeitenThe Theology of SexualityDercio MuhatuqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leadership Lessons From Great Past PresidentsDokument3 SeitenLeadership Lessons From Great Past Presidentsakhtar140Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dashboard Design Part 2 v1Dokument17 SeitenDashboard Design Part 2 v1Bea BoocNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary Bildungsroman: A Study of Psycho-Sociological Aspects of Father-Son Relationship in Khaled Hosseini's The Kite RunnerDokument10 SeitenContemporary Bildungsroman: A Study of Psycho-Sociological Aspects of Father-Son Relationship in Khaled Hosseini's The Kite RunnerMarwa Bou HatoumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romeo and Juliet Activities Cheat SheetDokument2 SeitenRomeo and Juliet Activities Cheat Sheetapi-427826649Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yoga Sutra PatanjaliDokument9 SeitenYoga Sutra PatanjaliMiswantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Master Ching Hai's God's Direct Contact - The Way To Reach PeaceDokument106 SeitenSupreme Master Ching Hai's God's Direct Contact - The Way To Reach PeaceseegodwhilelivingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mse 600Dokument99 SeitenMse 600Nico GeotinaNoch keine Bewertungen