Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Bauman: What Fourth Amendment?

Hochgeladen von

New England Law ReviewCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Bauman: What Fourth Amendment?

Hochgeladen von

New England Law ReviewCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

BAUMAN_FINAL.

DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

What Fourth Amendment? Maryland v. King: Another Supreme Court Case Eroding the Charter of Our Existence

BRETT A. BAUMAN*

ast term the United States Supreme Court decided a caseMaryland v. Kingthat continues the erosion of this countrys constitutional protections.1 At first blush, it may seem that allowing deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) collection and analysis of detainees upon arrest for serious crimes will aid law enforcement. Indeed, advocates in favor of DNA collection argue that these searches 2 assist the government in apprehending and convicting our most dangerous citizens, thus making society safer for everyone. 3 Yet, there are two important interests that have been eroded by this decision: (1) our Fourth Amendment protections against unreasonable and warrantless searches and seizures; and (2) the presumption of innocence. In King, the Supreme Courtwith a slim majorityheld that the collection of DNA through a cheek-swab and analysis of DNA from an arrestee is reasonable under the Fourth Amendment. 4 Comparing it to police booking procedures, the Courts majority concluded that there are five reasons why it considers these searches legal: (1) identification; (2) the safety of the facility staff of the jails and the detainees within the jails; (3) securing the accuseds presence at trial; (4) the determination of pretrial detention or conditions of release; and (5) acquitting those convicted of

* Attorney, Committee for Public Counsel Services Public Defender Division; B.A., Criminal Justice, Florida Atlantic University (2010); J.D., New England Law | Boston, magna cum laude (2013). I want to thank all those who have been instrumental in my life and career, including, but not limited to, my father, Jeffrey H. Bauman, and my grandfather, Bernard Bauman. 1 See generally 133 S. Ct. 1958 (2013). 2 Indeed, these are considered searches. See id. at 196869. 3 Advancing Justice Through DNA Technology: Using DNA to Solve Crimes , U.S. DEPT OF JUST., http://www.justice.gov/ag/dnapolicybook_solve_crimes.htm (last visited Feb. 7, 2014).

4

King, 133 S. Ct. at 1980.

47

BAUMAN_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

48

New England Law Review On Remand

v. 48 | 47

crimes they did not commit.5 The Court also relied on the judicial officer s probable cause finding; the arrestees diminished expectation of privacy; the minimal intrusion of a buccal swab; the analysis of the so-called junk DNA;6 and the destruction of the sample following an acquittal, pardon, or vacated sentence for which no new trial is permitted. 7 The Courts conclusions are flawed in many respects. First, DNA is not used solely for identification purposes; 8 rather, it is used as an investigative tool for criminal prosecutions and crime solving.9 If fingerprints are taken and they adequately identify an individual, then DNA collection and analysis is unnecessary. 10 Yet, what DNA adds is the ability to solve past and future crimesan invaluable tool for law enforcement.11 Similarly intriguing is that fingerprints may be a better indicator of an individuals identity than DNA.12 Whereas the average response time for a fingerprint analysis is about twenty-seven minutes, it can take months to get the results from a DNA analysis.13 Also, while everyone has a distinct set of fingerprints, the same cannot be said about DNA.14 For instance, monozygotic twins share the same DNA; therefore, their identities are better distinguished through their fingerprints. 15 More disturbing is that the DNA collected is destroyed upon acquittal.16 Yet, if DNA collection and analysis were really about identification, like fingerprints, then the results would be retained indefinitely.17 Therefore,

Id. at 197174. Junk DNA is a term that is used to refer to non-genic stretches of DNA not presently recognized as being responsible for trait coding. United States v. Kincade, 379 F.3d 813, 818 (9th Cir. 2004) (en banc) (plurality opinion). The Court asserted that junk DNA, although dispositive for determining a persons identity, does not reveal any other characteristics like genetic traits. King, 133 S. Ct. at 1967. This conclusion, however, is misguided insofar as it conflicts with the advances in science and the recent discoveries regarding the plethora of information that junk DNA contains. See infra notes 32, 4650 and accompanying text.

6

King, 133 S. Ct. at 196768, 197880. United States v. Mitchell, 652 F.3d 387, 391, 415 16 (3d Cir. 2011); Brett A. Bauman, United States v. Mitchell: Warrantless DNA and a Whole New Meaning to the Strip Search , 47 NEW ENG. L. REV. 455, 469 (2012). 9 See Bauman, supra note 8, at 469. 10 King, 133 S. Ct. at 1989 (Scalia, J., dissenting). 11 Id. 12 Bauman, supra note 8, at 471. 13 King, 133 S. Ct. at 1987. 14 See Bauman, supra note 8, at 471. 15 Id. 16 See id. at 472. 17 See Daniel Engber, Does the FBI Have Your Fingerprints?: Find Out for 18 Bucks, SLATE (Apr. 22, 2005, 6:38 PM), http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/explainer/2005/04

8

BAUMAN_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

2014

What Fourth Amendment?

49

the conclusion that DNA collection and analysis is an identification tool is erroneous; it is nothing more than a method of artifice used to justify an irrational result. Second, even if DNA collection is used as a basis for keeping staff and other detainees safe in jails, it will be a very long time before DNA results are actually received.18 If an arrestee was detained, months could go by without an awareness of his violent propensities.19 Consequently, DNA collection and analysis could not be used to keep the staff and detainees safe. It is not possible to obtain the DNA results prior to the time when the arrestee is transported to the jail awaiting trial.20 Third, there are other mechanisms for securing an arrestee s presence at trial.21 For instance, bail has been used effectively for centuries to make sure that an accused person shows up to court.22 Using the Courts reasoning and considering the time it takes to analyze a DNA sample, 23 if DNA is collected at arrest, then a person who may have committed a past crime (if released on bail) would have even more of a reason to flee the jurisdiction to avoid prosecution.24 Even more, they may try to evade arrest wholly.25 The Courts conclusions suggest that it would be reasonable to collect DNA samples from everyone at birth to avoid these risks; yet, it is doubtful the Courtor the Founding Fatherswould agree with such a judgment.26

/does_the_fbi_have_your_fingerprints.html; see also Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System, FED. BUREAU OF INVESTIGATION, http://www.fbi.gov/aboutus/cjis/fingerprints_biometrics/iafis (last visited Feb. 7, 2014). 18 See supra note 13 and accompanying text. 19 See supra note 13 and accompanying text. 20 See Rick Visser & Greg Hampikian, When DNA Wont Work, 49 IDAHO L. REV. 39, 5253 (2012). See, e.g., Commonwealth v. Stuyvesant Ins. Co., 321 N.E.2d 811, 814 (Mass. 1975). TIMOTHY R. SCHNACKE ET AL., THE HISTORY OF BAIL AND PRETRIAL RELEASE, (Pretrial Justice Inst. 2010), http://www.pretrial.org/download/pji-reports/PJI-History%20of%20Bail

22 21

%20Revised%20Feb%202011.pdf. 23 [O]ne who ha[s] committed a prior [crime] might be inclined to flee . . . knowing that in every State a DNA sample would be taken . . . after his conviction . . . that would tie him to [a] more serious charge . . . . Maryland v. King, 133 S. Ct. 1958, 1973 (2013) (majority opinion).

24 See, e.g., Fugitive Investigations, Index, U.S. MARSHALS SERVICE, http://www.usmarshals .gov/investigations (last visited Feb. 7, 2014); OIG Most Wanted Fugitives, U.S. DEPT OF HEALTH & HUM. SERVICES, OFF. OF INSPECTOR GEN., https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/fugitives (last visited Feb. 7, 2014). 25 See James E. Guffey et al., Three-Strikes Laws and Police Officer Murders: Do the Data Indicate a Correlation?, 4 PROF. ISSUES IN CRIM. JUST. 9, 11 (2009), https://kucampus.kaplan.edu/

documentstore/docs09/pdf/picj/vol4/issue2/PICJ_V4N2.pdf. 26 King, 133 S. Ct. at 1989 (Scalia, J., dissenting).

BAUMAN_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

50

New England Law Review On Remand

v. 48 | 47

Fourth, as previously stated, the analysis of DNA could take months. 27 Considering this, the only way it could effectively play a role in a court s determination of whether an individual should be released on bailor what conditions should be imposed if released is if an individual is held without bail pending the DNA results.28 Sure, with the rapid advancement of technology, one day we may see DNA results within minutes. 29 However, since we are not there yet, this clearly should not have played a role in the Courts analysisyet it did.30 More unnerving is that the Court was all too eager to consider technological advancements in DNA analysis, but was unwilling to consider the advancement of research regarding junk DNA and the privacy implications attached to it.31 Fifth, it is improper to justify warrantless DNA collection by citing the remote possibility that someone who was wrongfully accused of a crime may be acquitted.32 If a crime scene contained DNA evidence, someone who was arrested would be acquitted once his or her DNA was tested. 33 The reader may ask: Well, if the DNA cannot be tested upon arrest, then how can their DNA be collected? The answer is simple: if there is probable cause to arrest the person for the crime, then there would also likely be probable cause to obtain a warrant to collect their DNA if DNA was left at the scene.34 Thus, justifying the deprivation of liberties by the mere possibility that one will be acquitted is fallacious reasoning at best. A judges or magistrates probable cause finding for one crime is no justification to conduct a search for evidence of another crime. 35 This is not an identification procedure; rather, it is a fishing expedition: an attempt to collect evidence to investigate, and even solve, past and future crimes. 36 It is akin to searching a home for evidence after an arrest for a serious offense on the off chance the officer may find further evidence that would

27 28

See supra note 13 and accompanying text. See supra note 13 and accompanying text. 29 King, 133 S. Ct. at 1977 (majority opinion) (citing Attorney General DeWine Announces Significant Drop in DNA Turnaround Time, OHIO ATTY GEN. (Jan. 4, 2013), http://ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Media/News-Releases/January-2013/Attorney-GeneralDeWine-Announces-Significant-Drop). See id. at 197677. See infra text and accompanying notes 4649. 32 See Jesika S. Wehunt, Drawing the Line: DNA Databasing at Arrest and Subsequent Expungement, 29 GA. ST. U. L. REV. 1063, 106970 (2013). 33 See DNA Exonerations Nationwide, INNOCENCE PROJECT, http://www.innocenceproject .org/Content/DNA_Exonerations_Nationwide.php (last visited Feb. 7, 2014). 34 See WILLIAM E. RINGEL, SEARCHES AND SEIZURES ARRESTS AND CONFESSIONS 4:2 (2d ed. 2013).

31 35 36 30

Bauman, supra note 8, at 473. United States v. Mitchell, 652 F.3d 387, 423 (3d Cir. 2011) (Rendell, J., dissenting).

BAUMAN_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

2014

What Fourth Amendment?

51

implicate the arrested individual in other crimes.37 Such a position would not, and could not, ever be justified by the courts so long as the Fourth Amendment remains law.38 Just as the Fourth Amendment protects homes from warrantless searches, it also protects people in fact persons are listed first in the text of the Fourth Amendment.39 Although arrestees have a diminished expectation of privacy, this does not mean they are without constitutional protections.40 Actually, arrestees enjoy a most cherished liberty: the presumption of innocence. 41 The mere fact that these individuals were arrested does not mean that they forfeit all of their Fourth Amendment rights.42 Also, even concluding that the buccal swab procedure is a minimal intrusion does not mean that it lacks Fourth Amendment scrutiny.43 A slight intrusion is still an intrusion and it infringes upon an expectation of privacy. 44 Similarly, even if the collection of DNA through a buccal swab is minimally intrusive, the DNA analysis is a serious intrusion on an individual s privacy interestsan issue the Court refused to consider.45 More unavailing is the majoritys reasoning that junk DNA is ineffective and does not reveal an individual s genetic make-up.46 DNA termed junk DNA is not really junk at all.47 In fact, this junk DNA contains information regarding an individual s genetic structure.48 With the rapid advancement in science and technology, there is no telling how much

Bauman, supra note 8, at 473. Id. 39 U.S. CONST. amend. IV. [T]he Fourth Amendment protects people, not places. Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347, 351 (1967).

38

37

See In re Welfare of C.T.L., 722 N.W.2d 484, 49192 (Minn. Ct. App. 2006). See id. 42 See State v. Gardner, 984 N.E.2d 1025, 1026 1 (Ohio 2012); Bauman, supra note 8, at 469. 43 See Skinner v. Ry. Labor Execs. Assn, 489 U.S. 602, 616 (1989). 44 See Arizona v. Hicks, 480 U.S. 321, 32728 (1987) (holding invalid a seizure of stolen stereo equipment when a police officer had to move it to see the serial numbers); Skinner, 489 U.S. at 616 (reasoning that although a minimal intrusion, the physical intrusion of penetrating beneath a persons skin to collect a blood sample is a Fourth Amendment search and the further chemical analysis of the blood is a separate search); Minnesota v. Dickerson, 508 U.S. 366, 37779 (1993) (concluding a search invalid when a police officer manipulated his fingers during a Terry frisk to determine the defendant had contraband on him).

41 45 Charles J. Nerko, Note, Assessing Fourth Amendment Challenges to DNA Extraction Statutes After Samson v. California, 77 FORDHAM L. REV. 917, 935 (2008).

40

See id. Clive Cookson, Regulatory Genes Found in Junk DNA, FIN. TIMES (London), June 4, 2004, at 11 (reporting that junk DNA actually contains essential functions which scientists are just discovering).

47 48

46

See id.

BAUMAN_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE)

2/10/2014 4:37 PM

52

New England Law Review On Remand

v. 48 | 47

information may be available from this so-called junk DNA.49 Moreover, although a DNA sample is destroyed after an acquittal or pardon, this is just further evidence that the collection of the DNA is not for identification purposes at all: if DNA collection and analysis were for identification purposes, then there would be no reason to destroy it after an acquittal. 50 After all, fingerprints are not destroyed after one is acquitted. 51 Also, if the DNA collection was solely for identification, the Court itself would not have limited it to only serious offense[s].52 To those who value the protections afforded by the United States Constitution, it is clear that the King majority went to great pains to justify collecting DNA.53 At this point, it should be noted that this article is by no means arguing that DNA should never be collected. In fact, this article is trying to argue that DNA should only be collected according to a search warrant, an exception to a search warrant (i.e. exigent circumstances), or following a conviction. What the Court did in King was further erode Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. It remains to be seen what further implications this decision will have on our societys fundamental principles, and how the Court will rely on this decision in the future to uphold further intrusions on an individual s privacy.

49 Justin Gillis, Genetic Code of Mouse Published; Comparison with Human Genome Indicates Junk DNA May Be Vital, WASH. POST, Dec. 5, 2002, at A1 (reporting that scientists may have to abandon the term junk DNA because of new discoveries concerning the utility of these stretches of genetic material); Joe Palca, Don't Throw It Out: Junk DNA Essential in Evolution (NPR radio broadcast Aug. 18, 2011), available at http://www.npr.org/2011/08/19/139757702/

dont-throw-it-out-junk-dna-essential-in-evolution (Its perfectly obvious now [that] what we used to call junk DNA is actually chock-filled with the information that builds out organisms.). 50 See Maryland v. King, 133 S. Ct. 1958, 1967 (2013). 51 See Engber supra note 17. 52 See King, 133 S. Ct. at 1980. Also, it is not clear what the Court really considers a serious offense. See id.

53

See generally id. at 1958.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- HRM in NestleDokument21 SeitenHRM in NestleKrishna Jakhetiya100% (1)

- Suffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsDokument44 SeitenSuffolk County Substance Abuse ProgramsGrant ParpanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Descartes and The JesuitsDokument5 SeitenDescartes and The JesuitsJuan Pablo Roldán0% (3)

- Reforming The NYPD and Its Enablers Who Thwart ReformDokument44 SeitenReforming The NYPD and Its Enablers Who Thwart ReformNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reformation of The Supreme Court: Keeping Politics OutDokument22 SeitenReformation of The Supreme Court: Keeping Politics OutNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why State Constitutions MatterDokument12 SeitenWhy State Constitutions MatterNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Swear Not at All": Time To Abandon The Testimonial OathDokument52 Seiten"Swear Not at All": Time To Abandon The Testimonial OathNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section 43 (A) in A Vacuum: Cleaning Up False Advertising in An Unfair Competition MessDokument14 SeitenSection 43 (A) in A Vacuum: Cleaning Up False Advertising in An Unfair Competition MessNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- 101 99% Human and 1%animal? Patentable Subject Matter and Creating Organs Via Interspecies Blastocyst Complementation by Jerry I-H HsiaoDokument23 Seiten101 99% Human and 1%animal? Patentable Subject Matter and Creating Organs Via Interspecies Blastocyst Complementation by Jerry I-H HsiaoNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Combating The Opioid Crisis: The Department of Health and Human Services Must Update EMTALADokument21 SeitenCombating The Opioid Crisis: The Department of Health and Human Services Must Update EMTALANew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harvesting Hope: Regulating and Incentivizing Organ DonationDokument31 SeitenHarvesting Hope: Regulating and Incentivizing Organ DonationNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Massachusetts Sexually Dangerous Persons Statute: A Critique of The Unanimous Jury Verdict Requirement by Widmaier CharlesDokument17 SeitenThe Massachusetts Sexually Dangerous Persons Statute: A Critique of The Unanimous Jury Verdict Requirement by Widmaier CharlesNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Employment Discrimination: Pretext, Implicit Bias, and The Beast of BurdensDokument27 SeitenEmployment Discrimination: Pretext, Implicit Bias, and The Beast of BurdensNew England Law Review100% (1)

- The Fight Against Online Sex Trafficking: Why The Federal Government Should View The Internet As A Tool and Not A WeaponDokument16 SeitenThe Fight Against Online Sex Trafficking: Why The Federal Government Should View The Internet As A Tool and Not A WeaponNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outer Space and International Geography Article II and The Shape of Global OrderDokument29 SeitenOuter Space and International Geography Article II and The Shape of Global OrderNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mechanisms of Accountability Fundamental To An Independent JudiciaryDokument6 SeitenMechanisms of Accountability Fundamental To An Independent JudiciaryNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Secret Law and The Snowden Revelations: A Response To The Future of Foreign Intelligence: Privacy and Surveillance in A Digital Age, by Laura K. Donohue by HEIDI KITROSSERDokument10 SeitenSecret Law and The Snowden Revelations: A Response To The Future of Foreign Intelligence: Privacy and Surveillance in A Digital Age, by Laura K. Donohue by HEIDI KITROSSERNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trademarks and Twitter: The Costs and Benefits of Social Media On Trademark Strength, and What This Means For Internet-Savvy CelebsDokument25 SeitenTrademarks and Twitter: The Costs and Benefits of Social Media On Trademark Strength, and What This Means For Internet-Savvy CelebsNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- An "Obvious Truth": How Underfunded Public Defender Systems Violate Indigent Defendants' Right To CounselDokument30 SeitenAn "Obvious Truth": How Underfunded Public Defender Systems Violate Indigent Defendants' Right To CounselNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cuz I'm Young & I'm Black & My Hat's Real Low: Constitutional Rights To The Political Franchise For Parolees Under Equal Protection by Shaylen Roberts, Esq.Dokument33 SeitenCuz I'm Young & I'm Black & My Hat's Real Low: Constitutional Rights To The Political Franchise For Parolees Under Equal Protection by Shaylen Roberts, Esq.New England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ignorance Is Bliss: Why The Human Mind Prevents Defense Attorneys From Providing Zealous Representation While Knowing A Client Is GuiltyDokument25 SeitenIgnorance Is Bliss: Why The Human Mind Prevents Defense Attorneys From Providing Zealous Representation While Knowing A Client Is GuiltyNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- “The Legalization of Recreational Marijuana in Massachusetts and the Limits of Social Justice for Minorities and Communities Disproportionately Impacted by Prior Marijuana Laws and Drug Enforcement Policies”Dokument13 Seiten“The Legalization of Recreational Marijuana in Massachusetts and the Limits of Social Justice for Minorities and Communities Disproportionately Impacted by Prior Marijuana Laws and Drug Enforcement Policies”New England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Augustine and Estabrook: Defying The Third-Party Doctrine by Michael LockeDokument13 SeitenAugustine and Estabrook: Defying The Third-Party Doctrine by Michael LockeNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Death by 1000 Lawsuits: The Public Litigation in Response To The Opioid Crisis Will Mirror The Global Tobacco Settlement of The 1990s by Paul L. KeenanDokument26 SeitenDeath by 1000 Lawsuits: The Public Litigation in Response To The Opioid Crisis Will Mirror The Global Tobacco Settlement of The 1990s by Paul L. KeenanNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revealing A Necessary Evil: The United States Must Continue To Use Some Form of Domesticated Counter-Terrorism Program by Daniel R. GodefroiDokument17 SeitenRevealing A Necessary Evil: The United States Must Continue To Use Some Form of Domesticated Counter-Terrorism Program by Daniel R. GodefroiNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remnants of Information Privacy in The Modern Surveillance State by Lawrence FriedmanDokument15 SeitenRemnants of Information Privacy in The Modern Surveillance State by Lawrence FriedmanNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ojukwu Final 3Dokument26 SeitenOjukwu Final 3New England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Shadowy Law of Modern Surveillance by Gina AbbadessaDokument3 SeitenThe Shadowy Law of Modern Surveillance by Gina AbbadessaNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Light On State Constitutional ChangeDokument4 SeitenNew Light On State Constitutional ChangeNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Citizens Commission For The 28 Amendment: Massachusetts Advances Constitutional Reform of Our Broken Political SystemDokument8 SeitenA Citizens Commission For The 28 Amendment: Massachusetts Advances Constitutional Reform of Our Broken Political SystemNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- V.51-3 TOC FinalDokument2 SeitenV.51-3 TOC FinalNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Collins Final 3Dokument20 SeitenCollins Final 3New England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unconstitutional Constitutional Change by Courts: NtroductionDokument23 SeitenUnconstitutional Constitutional Change by Courts: NtroductionNew England Law ReviewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specific Relief Act, 1963Dokument23 SeitenSpecific Relief Act, 1963Saahiel Sharrma0% (1)

- Joseph Minh Van Phase in Teaching Plan Spring 2021Dokument3 SeitenJoseph Minh Van Phase in Teaching Plan Spring 2021api-540705173Noch keine Bewertungen

- Channarapayttana LandDokument8 SeitenChannarapayttana Landnagaraja.raj.1189Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rong Sun ComplaintDokument22 SeitenRong Sun ComplaintErin LaviolaNoch keine Bewertungen

- La Bugal BLaan Tribal Association Inc. vs. RamosDokument62 SeitenLa Bugal BLaan Tribal Association Inc. vs. RamosAKnownKneeMouseeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mock 10 Econ PPR 2Dokument4 SeitenMock 10 Econ PPR 2binoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Military Laws in India - A Critical Analysis of The Enforcement Mechanism - IPleadersDokument13 SeitenMilitary Laws in India - A Critical Analysis of The Enforcement Mechanism - IPleadersEswar StarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ati - Atihan Term PlanDokument9 SeitenAti - Atihan Term PlanKay VirreyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Southwest CaseDokument13 SeitenSouthwest CaseBhuvnesh PrakashNoch keine Bewertungen

- PDF Issue 1 PDFDokument128 SeitenPDF Issue 1 PDFfabrignani@yahoo.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Entrepreneurship: The Entrepreneur, The Individual That SteersDokument11 SeitenEntrepreneurship: The Entrepreneur, The Individual That SteersJohn Paulo Sayo0% (1)

- Adidas Case StudyDokument5 SeitenAdidas Case StudyToSeeTobeSeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problem Solving and Decision MakingDokument14 SeitenProblem Solving and Decision Makingabhiscribd5103Noch keine Bewertungen

- Citizen Charter Of: Indian Oil Corporation LimitedDokument9 SeitenCitizen Charter Of: Indian Oil Corporation LimitedAbhijit SenNoch keine Bewertungen

- RBI ResearchDokument8 SeitenRBI ResearchShubhani MittalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cartographie Startups Françaises - RHDokument2 SeitenCartographie Startups Françaises - RHSandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roof Structure Collapse Report - HongkongDokument11 SeitenRoof Structure Collapse Report - HongkongEmdad YusufNoch keine Bewertungen

- 755 1 Air India Commits Over US$400m To Fully Refurbish Existing Widebody Aircraft Cabin InteriorsDokument3 Seiten755 1 Air India Commits Over US$400m To Fully Refurbish Existing Widebody Aircraft Cabin InteriorsuhjdrftNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prof. Sujata Patel Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Anurekha Chari Wagh Department of Sociology, Savitribaiphule Pune UniversityDokument19 SeitenProf. Sujata Patel Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad Anurekha Chari Wagh Department of Sociology, Savitribaiphule Pune UniversityHarish KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prayer For World Teachers Day: Author: Dr. Anthony CuschieriDokument1 SeitePrayer For World Teachers Day: Author: Dr. Anthony CuschieriJulian ChackoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Automated Behaviour Monitoring (ABM)Dokument2 SeitenAutomated Behaviour Monitoring (ABM)prabumnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Dokument2 SeitenDewi Handariatul Mahmudah 20231125 122603 0000Dewi Handariatul MahmudahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshDokument9 SeitenImpact of Money Supply On Economic Growth of BangladeshSarabul Islam Sajbir100% (2)

- EN 12953-8-2001 - enDokument10 SeitenEN 12953-8-2001 - enעקיבא אסNoch keine Bewertungen

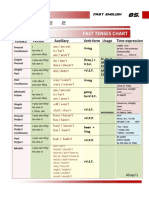

- Table 2: Fast Tenses ChartDokument5 SeitenTable 2: Fast Tenses ChartAngel Julian HernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Text and Meaning in Stanley FishDokument5 SeitenText and Meaning in Stanley FishparthNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flipkart Labels 23 Apr 2024 10 18Dokument4 SeitenFlipkart Labels 23 Apr 2024 10 18Giri KanyakumariNoch keine Bewertungen