Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Flowchart

Hochgeladen von

Elisse StephanieCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Flowchart

Hochgeladen von

Elisse StephanieCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Document title: Publication date: Document number: Replaces document: Author: Audience: Exclusions: Review date: Endorsed by:

Primary postpartum haemorrhage July 2009 MN09.1-V2-R11 MN0907.1-V1-R11 Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program Health professionals in Queensland public and private maternity services Prophylactic preparedness for PPH in high risk women July 2011 Statewide Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Network QH Patient Safety and Quality Executive Committee Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program: Email: MN-Guidelines@health.qld.gov.au URL: www.health.qld.gov.au/qcg

Contact:

Disclaimer These guidelines have been prepared to promote and facilitate standardisation and consistency of practice, using a multidisciplinary approach. Information in this guideline is current at time of publication. Queensland Health does not accept liability to any person for loss or damage incurred as a result of reliance upon the material contained in this guideline. Clinical material offered in this guideline does not replace or remove clinical judgement or the professional care and duty necessary for each specific patient case. Clinical care carried out in accordance with this guideline should be provided within the context of locally available resources and expertise. This Guideline does not address all elements of standard practice and assumes that individual clinicians are responsible to: Discuss care with consumers in an environment that is culturally appropriate and which enables respectful confidential discussion. This includes the use of interpreter services where necessary Advise consumers of their choice and ensure informed consent is obtained. Provide care within scope of practice, meet all legislative requirements and maintain standards of professional conduct Apply standard precautions and additional precautions as necessary, when delivering care Document all care in accordance with mandatory and local requirements

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 2.5 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/au/ State of Queensland (Queensland Health) 2010 In essence you are free to copy and communicate the work in its current form for non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the authors and abide by the licence terms. You may not alter or adapt the work in any way. For permissions beyond the scope of this licence contact: Intellectual Property Officer, Queensland Health, GPO Box 48, Brisbane Qld 4001, email ip_officer@health.qld.gov.au , phone (07) 3234 1479. For further information contact Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program, RBWH Post Office, Herston Qld 4029, email MN-Guidelines@health.qld.gov.au phone (07) 3131 6777.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 2 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

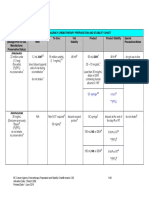

Flowchart: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 3 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Abbreviations

BP coag DIC FBC FFP g G&H IM IU IV kg mcg mg min ml MTP N/Saline PPH PRBC QAS rFVlla RSQ X-Match Blood pressure Coagulation profile Disseminated intravascular coagulation Full blood count Fresh frozen plasma Gauge Group and hold Intra-muscular International units Intravenous Kilograms Micrograms Milligrams Minutes Millilitres Massive transfusion protocol Normal saline (0.9% Sodium Chloride) Postpartum haemorrhage Packed red blood cells Queensland ambulance service Recombinant activated factor VII Retrieval services Queensland Crossmatch

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 4 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Table of Contents Introduction.....................................................................................................................................6 1.1 Definition ................................................................................................................................6 1.2 Risk factors for PPH ..............................................................................................................6 1.3 Common causes of PPH .......................................................................................................6 1.4 Active management of the third stage of labour ....................................................................6 2 Assessment and management.......................................................................................................7 2.1 Resuscitation .........................................................................................................................7 2.2 Management of atonic uterus ................................................................................................7 2.3 Management of genital trauma ..............................................................................................8 2.4 Management of retained placenta .........................................................................................8 2.5 Advanced medical management of non-responsive PPH .....................................................9 2.5.1 Balloon tamponade............................................................................................................9 2.5.2 Angiographic embolisation...............................................................................................10 2.6 Surgical management of non-responsive PPH....................................................................10 2.6.1 Fundal compression suture .............................................................................................10 2.6.2 Bilateral uterine artery ligation .........................................................................................11 2.6.3 Bilateral internal iliac artery ligation .................................................................................11 2.6.4 Hysterectomy ...................................................................................................................11 2.7 Coagulopathy.......................................................................................................................11 2.7.1 Volume replacement........................................................................................................12 2.7.2 Blood component therapy................................................................................................12 2.7.3 Cryoprecipitate.................................................................................................................12 2.7.4 Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) .......................................................................12 3 Ongoing care ................................................................................................................................13 3.1 Inter-hospital transfer...........................................................................................................13 3.2 Documentation.....................................................................................................................13 3.3 Feeding support...................................................................................................................13 3.4 Social work...........................................................................................................................13 3.5 Physiotherapy ......................................................................................................................13 3.6 Critical incident stress management....................................................................................13 References ..........................................................................................................................................14 Appendix A: Drug table........................................................................................................................15 Appendix B: Acknowledgements .........................................................................................................16 1 Table of figures Figure 1: Bimanual compression ...........................................................................................................8 Figure 2: Balloon tamponade ................................................................................................................9 Figure 3: Balloon positioning .................................................................................................................9 Figure 4: Compression suture .............................................................................................................11 Figure 5: Bilateral uterine artery ligation..............................................................................................11 List of tables Table 1: Observation table ....................................................................................................................7

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 5 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Introduction

1.1 Definition

Postpartum haemorrhage (PPH) can be defined clinically as any amount of blood loss that results in haemodynamic instability1. Traditional definitions state that PPH is a blood loss of 500 ml or more during puerperium, with severe PPH occurring with a blood loss of 1000 ml or more1,2. PPH is classified as primary PPH, occurring within the first 24 hours postpartum and secondary PPH occurring between 24 hours and up to six weeks postpartum3.

1.2 Risk factors for PPH

Increased maternal age History of previous PPH Antepartum/intrapartum haemorrhage Anaemia Over-distended uterus (e.g. Multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios) Grand multi-parity Prolonged labour Precipitate labour Placenta praevia Placental abruption Fibroids Von Willebrand disease.

1.3 Common causes of PPH

The main causes of PPH can be categorised under the following headings4: tone: o atonic uterus (the most common cause). trauma: o genital tract trauma o ruptured uterus o uterine inversion. tissue: o retained products of conception o adherent placenta. thrombin: o coagulation abnormalities.

1.4 Active management of the third stage of labour

Actively managing the third stage of labour has been shown to help prevent postpartum haemorrhage 5, 6. Active management entails: oxytocic administration: o syntocinon o syntometrine (contra-indicated with severe hypertension and cardiac disease). cord clamping controlled cord traction and fundal support with signs of placental separation.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 6 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Assessment and management

2.1 Resuscitation

If resuscitation is required7,8: call for help lie woman flat and provide ongoing reassurance massage the fundus to stimulate a contraction administer oxygen via oxygen mask insert 14 or 16 g intravenous cannulae bilaterally and obtain blood sample: o send blood sample for full blood count, electrolytes, liver function, coagulation profile and cross match. commence intravenous volume replacement, warmed if possible: o do not wait for signs of shock before commencing o give 23 litres of Hartmanns solution for each litre of estimated blood loss o use rapid infusion sets, pump sets or pressure bags o reassess. record pulse, respirations and blood pressure, and check every five minutes provide early blood transfusion / blood component therapy if bleeding is massive or progressive use blankets to keep woman warm obtain temperature, oxygen saturation and assess level of consciousness insert in-dwelling urinary catheter and monitor urine output observe signs and symptoms of shock to guide management: o blood volume loss is frequently underestimated. ascertain cause of PPH.

Table 1: Observation table Blood volume loss 5001000 ml (1015%) 10001500 ml (1525%) 15002000 ml (2530%) 20003000 ml (3545%) BP (systolic) Normal Slight fall (80100 mm Hg) Moderate fall (7080 mm Hg) Marked fall (5070 mm Hg) Pulse Normal > 100 > 120 > 140 Signs & symptoms Palpitation, dizziness Weakness, tachycardia, sweating Restlessness, pallor, oliguria Collapse, air hunger, anuria Degree of shock Compensated Mild Moderate Severe

2.2 Management of atonic uterus

In the case of atonic uterus 8,9: massage the fundus to stimulate contraction ensure active management of third stage has occurred check placenta for completeness administer intravenous Ergometrine 250 mcg 7,8,10 OR intravenous Oxytocin 510 IU if blood pressure is elevated commence intravenous Oxytocin infusion 10 IU per hour as a sideline.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 7 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

If bleeding continues and uterine tone has not improved with the above management: administer 8001000 mcg Misoprostol per rectum and/or administer intramyometrial Prostaglandin F2 500 mcg (ensure medication dilutedrefer to drug table) insert urinary in-dwelling catheter apply bi-manual compression (Figure 1)12: o compress uterus between external hand placed on the fundus, and intravaginal hand o avoid vigorous massage that can injure large vessels of the broad ligament. transfer to theatre. Once in theatre: ensure that the uterus is empty by manual exploration of the uterine cavity if retained placenta, follow management of retained placenta (see Section 2.4).

Figure 1: Bimanual compression

If bleeding and non-responsive to above, go to advanced medical or surgical management

2.3 Management of genital trauma

When genital trauma is considered a potential cause of bleeding: assess for genital tract trauma: o place in lithotomy position o inspect vagina and cervix for lacerations, clamp any bleeding vessels or apply pressure and repair as necessary o transfer to theatre to facilitate repair if necessary. If excessive loss persists and is not related to a lower genital tract laceration, consider the possibility that the placenta has not been completely delivered.

2.4 Management of retained placenta

When retained placenta is the likely cause of bleeding: ensure active management of the third stage of labour has occurred perform vaginal examination to establish if placenta is trapped or adherent remove placenta if in vagina.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 8 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

If placenta remains in-situ: repeat dose of Oxytocin 10 IU IMI or 510 IU slow IVI insert in-dwelling urinary catheter consider using portable ultrasound if available to determine if placenta has separated and its location prepare for transfer to theatre for manual removal of placenta, or if theatre not available, consider manual removal of placenta under sedation using Nitrous Oxide, Midazolam, Fentanyl or Ketamine. While in theatre: explore the uterine cavity for signs of uterine rupture4: o perform curettage if retained products are suspected o check for cervical, vaginal and perineal trauma, and repair as necessary.

2.5 Advanced medical management of non-responsive PPH

If bleeding continues in spite of the above management: continue maternal resuscitation and fluid replacement consider activating a massive transfusion protocol if available. The following techniques should be performed by suitably qualified clinicians in the operating theatre. 2.5.1 Balloon tamponade Intra-uterine balloons, such as the Bakri balloon (illustrated in Figure 2)10 can be inserted into a contracting uterus. Balloon devices are not effective in a uterus that contains retained products or excessive blood. They are of more benefit to lower segment bleeding as gentle traction can be applied to further enhance the tamponade10. Tamponade balloons are also able to facilitate drainage of blood from the uterine cavity. The process for using the intra-uterine balloon is as follows10: insert the end of the balloon through the cervix into the uterine cavity, ensuring the balloon is completely inside the uterus (Figure 3) Inflate the balloon with sufficient volume of warm sterile saline (approx 250500 ml); the uterus should now be firm with minimal blood loss Commence broad spectrum antibiotic cover Continue or commence oxytocic infusion. If bleeding is not controlled, remove the balloon and attempt further management options.

Figure 2: Balloon tamponade

Figure 3: Balloon positioning

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 9 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

If the bleeding is controlled, remove the balloon when the bleeding subsideswithin 12 to 24 hours9,10. To remove the balloon8,10: an anaesthetic is not necessary ensure specialist care is available in case bleeding recommences gradually deflate the balloon by removing 100 ml per hour monitor for increased blood loss.

2.5.2 Angiographic embolisation Angiographic embolisation is a highly effective technique for abating bleeding, with success rates of approximately 90 per cent7,8,9,12. The procedure, which is relatively safe, allows for selective embolisation of vessels and preserves fertility12. Angiographic embolisation is of great value in elective cases with a high-risk of PPH, such as placenta accreta7,10,13. However, there are some logistical limitations with this technique. An interventional radiologist is required, along with the necessary radiological infrastructure and equipment7,13,14.The procedure can take about 60 minutes to complete. The use of angiographic embolisation is appropriate when: an interventional radiologist and necessary angiographic equipment are readily available13 the PPH is a continuing slow haemorrhage11 there is time to perform the procedure, and the patient is stable 7,14 .

2.6 Surgical management of non-responsive PPH

If bleeding continues in spite of the above management: continue maternal resuscitation and fluid replacement consider activating a massive transfusion protocol. The following surgical management options are available and should be performed by suitably qualified clinicians in the operating theatre. 2.6.1 Fundal compression suture Fundal compression sutures, such as the B-Lynch suture, are of value when bleeding is stemmed with compression techniques such as bimanual compression (figure 1)7,9,13. The role of the compression suture is to maintain compression.10 Compression sutures may be an effective alternative to hysterectomy, maintaining fertility7. The technique is performed at laparotomy or caesarean section using the following process: (re) open the abdomen and (re) open the uterus check the uterine cavity for bleeding sites that might be oversewn test before using the B-Lynch suture using bimanual compression and swabbing the vaginaif bleeding is controlled temporarily in this fashion the B-Lynch stitch is likely to be effective.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 10 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Figure 48 provides a graphical guide to the application of the compression suture.

Figure 4: Compression suture

2.6.2 Bilateral uterine artery ligation Bilateral uterine artery ligation (Figure 5)12 has been described as a simple and effective technique for the control of intractable PPH10.

Figure 5: Bilateral uterine artery ligation

2.6.3 Bilateral internal iliac artery ligation This procedure can be effective in reducing bleeding from all genital tract sources, and may avoid the need for hysterectomy7. This complex procedure must be performed by an experienced surgeon. Before progressing to hysterectomy, consider the use of recombinant activated factor VII if not contraindicated (see Section 2.7.4) 2.6.4 Hysterectomy The decision to perform a hysterectomy can be difficult to make; however, given its curative outcome, the decision should be made early. This is especially so for those women who have uncontrolled bleeding that has not responded to the above management options.

2.7 Coagulopathy

It is important to monitor the coagulation profile for changes. Circulating volume loss can be managed in the short term with crystalloid fluid. This can be followed as necessary with blood component therapy or by activating a massive transfusion protocol if the bleeding is ongoing or severe. Look for signs that blood is no longer clotting (e.g. petechial bleeds, subconjunctival haemorrhage, oozing from puncture sites) as these could indicate coagulopathy changes.4 Involve a haematologist to help manage the coagulation.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 11 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

2.7.1 Volume replacement Ensure bilateral 16 g intravenous access is in-situ and patent Give 23 litres of Hartmanns solution for each litre of estimated blood loss Use rapid infusion sets, pump sets or pressure bags Reassess If signs of shock, or if bleeding continues, commence blood component therapy or a massive transfusion protocol.

2.7.2 Blood component therapy Blood component therapy provides oxygen carrying capacity to the circulating volume, plus components to aid in clotting. The following blood component therapy for severe obstetric haemorrhage is recommended15. a) 4 units packed red blood cells (PRBC: Group specific or O Neg if unavailable) b) coagulopathy correction o 4 units PRBC o 4 units fresh frozen plasma (FFP) o single adult dose of platelets c) repeat PRBC, FFP and platelets d) administer calcium as appropriate. Repeat b) and c) as necessary. 2.7.3 Cryoprecipitate Cryoprecipitate at one unit per 10 kg body weight should be considered when16,17: clinical bleeding is present disseminated intravascular coagulation is present fibrinogen levels are lower than 1.0 g/L. 2.7.4 Recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) The use of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) in the management of bleeding in PPH is offlabel and, as such, its use rests with the prescribing clinician. It can be used for patients with religious beliefs that forbid the administration of blood products. The decision to use rFVIIa should occur when15: all previously mentioned non-surgical and surgical attempts, other than hysterectomy, have been attempted to stop the bleeding a centre is not resourced for the above surgical procedures. In these cases rFVIIa can be given earlier 812 units of PRBC have been administered, and bleeding continues. The administration of rFVIIa15: 90 mcg/kg (rounded to nearest vial) is administered as a single bolus intravenous injection over three to five minutes allow 20 minutes, and if bleeding is ongoing, check the following: temperature acidaemia serum calcium platelets and fibrinogen deliver a second dose of rFVIIa 90 mcg/kg as a single bolus intravenous injection over three to five minutes consider hysterectomy if bleeding persists after these two doses. Notify the Haemostasis Registry if rFVIIa is given: www.med.monash.edu.au/epidemiology/traumaepi/haemostasis.html

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 12 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Ongoing care

3.1 Inter-hospital transfer

The decision to transfer the critically ill or high-risk obstetric patient requiring a higher level of care should be made early. This will ensure that early specialist advice can be sought, and appropriate clinical crewing, efficient tasking of retrieval services as well as determining the destination facility can be arranged quickly. For an obstetric patient greater than 20 weeks gestation requiring a nurse and/or medical escort to facilitate a safe transfer, contact Retrieval Services Queensland on 1300 799 127. Your call will be directed to an obstetric registrar and/or consultant, and to an intensivist if necessary. If the obstetric patient is stable and does not require a medical or nursing escort, the referring centre should contact the receiving facility directly to arrange a bed. The road transport can be booked through the Queensland Ambulance Service on 13 12 33. Please note that if you are unsure about the level of escort or mode of transport required, call for advice on 1300 799 127. Ensure all documentation is completed prior to transfer.

3.2 Documentation

Partogram Vitals signs Medication chart Fluid order sheet Fluid balance chart Pathology results Medical notes Clinical pathways Midwifery notes Allied health notes Peri-natal data sheet Incident report.

3.3 Feeding support

Breastfeeding should be established as soon as practical with the support of a midwife or lactation consultant.

3.4 Social work

If necessary, a referral should be made to a social worker who can is assist in providing support to the family and support network.

3.5 Physiotherapy

Early referral to a physiotherapist will ensure early interventions are initiated in a timely manner.

3.6 Critical incident stress management

Immediate post-event debriefing for staff is essential. Debriefing can be provided locally or, by the Employee Assistance Service.

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 13 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary postpartum haemorrhage

References

1. New South Wales Department of HealthPrimary Health and Community Partnerships. Policy Directive. Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH)Framework for Prevention, Early Recognition & Management.[Online]. 2005 [cited 2009 Feb12]. Available from: URL:http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/policies/PD/2005/PD2005_264.html 2. Mousa HA, Alfirevic Z. Treatment for primary postpartum haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003249. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003249.pub2. 3. Kominiarek MA, Kilpatrick SJ. Postpartum haemorrhage: a recurring pregnancy complication. Semin Perinatol 2007; 31(3):15966. 4. Anderson J, Etches D. Postpartum Haemorrhage. In: Damos JD, Eisinger SH, Baxley EG, editors. Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics Course Syllabus 4th ed. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2008. 5. Prendiville WJP, Elbourne D, McDonald SJ. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD000007. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000007. 6. Cotter AM, Ness A, Tolosa JE. Prophylactic oxytocin for the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD001808. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001808. 7. Ramanathan G, Arulkumaran S. Postpartum haemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol 2006;(16): 613.

8. Wise A, Clark V. Strategies to manage major obstetric haemorrhage. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008;(21):28187. 9. Dildy GA. Postpartum Hemorrhage: New management options. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2002; 45(2):33044.

10. Somerset D. The emergency management of catastrophic obstetric haemorrhage. O & G Magazine [online]. 2006 [cited 2009 Feb 2]; 8(4):1822. Available from: URL:http://www.ranzcog.edu.au/publications/o-g_pdfs/O&G-Summer2006/The%20emergency%20management%20of%20catastrophic%20obstetric%20haemorrhage%20%20David%20Somerset.pdf 11. Burridge N, editor. Australian Injectable Drugs Handbook. 4th ed. Collingwood: Society of Hospital Pharmacists Australia; 2008. 12. Francois KE, Foley MR. Antepartum and Postpartum Hemorrhage. In: Gabbe SG, Niebyl JR, Simpson JL, editors. Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone Elseiver; 2007. 13. Arulkumaran S, Walker JJ, Watkinson AF, Nicholson T, Kessel D, Patel J. The role of emergency and elective interventional radiology in postpartum haemorrhage. Good Practice No. 6 [Online]. 2007 [cited 2009 Feb 5]. Available from: URL:http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcog-corp/uploaded-files/GoodPractice6RoleEmergency2007.pdf 14. Schuurmans N, MacKinnon C, Lane C, Etches D. Prevention and management of postpartum haemorrhage. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 88 [Online]. 2000 [cited 2009 Feb 5]. Available from: URL:http://www.sogc.org/guidelines/public/88E-CPG-April2000.pdf 15. Welsh A, McLintock C, Gatt S, Somerset D, Popham P, Ogle R. Guidelines for the use of recombinant activated factor VII in massive obstetric haemorrhage. ANZJOG 2008; 48:1216. 16. National Health and Medical Research Council. Appropriate use of Fresh Frozen Plasma and Cryoprecipitate. Clinical Practice Guidelines [Online]. 2001 [cited 2009 Feb 5]. Available from: URL:http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/_files/cp80.pdf 17. Australian Red Cross Blood Service. Cryoprecipitate Product Information. [Online]. 2009 [cited 2009 Feb 5]. Available from: URL:http://www.manual.transfusion.com.au/Blood-Products/Cryoprecipitate.aspx

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 14 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary post partum haemorrhage

Appendix A: Drug table

Drug Name Stat drugs Oxytocin combined with Ergometrine (Syntometrine) Ergometrine Ergometrine Oxytocin (Syntocinon) Prostaglandin F2 1 ml (Syntocinon 5 units, Ergometrine 0.5mg) IM Contra-indicated with severe hypertension and cardiac disease Side effects: nausea, vomiting, raised BP As per Syntometrine As per Syntometrine Off-label use Prepare a 20 ml solution: Add 19 ml of N/Saline to 1 ml of a 5 mg/ml ampoule Final concentration 250 mcg/ml (dose = 2 ml) Repeat dose every 15 min as required Off-label use As a side line (eg. 40 IU in 1000 ml N/S at 250 ml/hr; or 30 IU in 500 ml N/S at 167 ml per hour) Blood component therapy Blood component therapy Blood component therapy New IV line; use 170200 micron filter Off-label use Repeat after 20 min if bleeding ongoing. Notify Monash Haemostasis registry Dose Route Comments

0.5 mg 0.25 mg 510 IU 500 mcg (2 ml) increments as required max 3 mg

IM IV IM / IV Intramyometrial

Misoprostol Infusions Oxytocin infusion 0.9% Sodium Chloride 1000 ml Hartmanns solution 1000 ml Packed red blood cells Fresh frozen plasma Platelets Cryoprecipitate Recombinant factor VIIa

8001000 mcg 10 IU per hour 1000 ml as necessary 1000 ml as necessary

PR IV IV IV

1unit/10 kg 90 mcg/kg (nearest ampoule)

IV (no min. time; max 4 hours IV over 35 min

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use

Page 15 of 16

Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guideline: Primary post partum haemorrhage

Appendix B: Acknowledgements

The Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program gratefully acknowledge the contribution of Queensland clinicians and other stakeholders who participated throughout the guideline development process particularly:

Working Party Clinical Lead Associate Professor Rebecca Kimble, Obstetrician, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Working Party Members Dr Bob Baade, Obstetrician, Ipswich Hospital Ms Karen Baker, Midwife, Mackay Base Hospital Dr Kathleen Braniff, Obstetrician, Mackay Base Hospital Ms Lynn Bush, Midwife, Gladstone Hospital Associate Professor Leonie Callaway, Obstetric Physician, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Dr Lindsay Cochrane, Obstetrician, Caboolture Hospital Ms Penny Dale, Midwife, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Professor Michael Humphrey, Clinical Advisor, Office of Rural and Remote Health Dr Catherine Hurn, Emergency Physician, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Dr Graeme Jackson, Obstetrician, Redcliffe Hospital Ms Sarah Kirby, Midwifery Educator, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Ms Wendy Lehfeldt, Midwife, Royal Flying Doctor Service Ms Catherine Love, Principal Project Officer, Clinical Practice Improvement Centre Ms Naida Lumsden, Principal Project Officer, Clinical Practice Improvement Centre Ms Pauline Lyon, Midwifery Educator, Centre for Health Care Improvement Ms Linda Pallett, Midwife, Nambour Hospital Marie Perry, Nurse Educator, Mt Isa Base Hospital Ms Jennifer Petty, Social Worker, Mater Health Services Ms Pamela Sepulveda, Midwife, Logan Hospital Dr Liana Tanda, Obstetrician, Caboolture Hospital Ms Mary Tredinnick, Pharmacist, Royal Brisbane and Womens Hospital Dr Danny Tucker, Obstetrician, The Townsville Hospital Ms Dushka Vujicic, Midwife, Logan Hospital

Program Team Associate Professor Rebecca Kimble, Director, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program Ms Joan Kennedy, Principal Program Officer, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Guidelines Program Ms Brenda Green, Principal Program Officer, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Guidelines Program October 2008 March 2009 Mr Stephen Aitchison, Program Officer, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Guidelines Program Mrs Catherine van den Berg, Program Officer, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Guidelines Program Steering Committee 08_09, Queensland Maternity and Neonatal Clinical Guidelines Program

Refer to online version, destroy printed copies after use Page 16 of 16

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- ATEM Switchers Operation Manual December 2014 PDFDokument913 SeitenATEM Switchers Operation Manual December 2014 PDFElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal DBDDokument11 SeitenJurnal DBDAkbar_Bako_Akb_153650% (2)

- Hipertensi JNC 8Dokument7 SeitenHipertensi JNC 8Elisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manual ZXHN F660Dokument30 SeitenManual ZXHN F660Emil PrecupNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hemorrhage Post PartumDokument18 SeitenHemorrhage Post PartumElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family Practice 2012 Hansen 63 8Dokument6 SeitenFamily Practice 2012 Hansen 63 8Elisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presentation Title: Subheading Goes HereDokument4 SeitenPresentation Title: Subheading Goes HereElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cushing Syndrome - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediDokument3 SeitenCushing Syndrome - MedlinePlus Medical EncyclopediElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cushing's Disease - UCLA Pituitary Tumor ProgramDokument4 SeitenCushing's Disease - UCLA Pituitary Tumor ProgramElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syphilis CongenitalDokument5 SeitenSyphilis CongenitalElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Istilah Dalam KedokteranDokument39 SeitenIstilah Dalam KedokteranElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Website Situs KedokteranDokument2 SeitenWebsite Situs KedokteranElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading Early Treatment With Prednisolone or Acyclovir in Bell'S PalsyDokument15 SeitenJournal Reading Early Treatment With Prednisolone or Acyclovir in Bell'S PalsyElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difficult AirwayDokument23 SeitenDifficult AirwayElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal Reading Early Treatment With Prednisolone or Acyclovir in Bell'S PalsyDokument15 SeitenJournal Reading Early Treatment With Prednisolone or Acyclovir in Bell'S PalsyElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pedi Airway 051123Dokument11 SeitenPedi Airway 051123Elisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antipsychotics QuestionDokument25 SeitenAntipsychotics QuestionElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difficult Airway AlgorthmDokument3 SeitenDifficult Airway AlgorthmElisse StephanieNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Dula-Tungkulin o Gampanin NG ProduksyonDokument12 SeitenDula-Tungkulin o Gampanin NG ProduksyonBernadette DuranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Para Lab 11Dokument3 SeitenPara Lab 11api-3743217Noch keine Bewertungen

- Biliran Province State University: Bipsu!Dokument3 SeitenBiliran Province State University: Bipsu!joyrena ochondraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Msds ChloroformDokument9 SeitenMsds ChloroformAhmad ArisandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Example Chapter 1Dokument8 SeitenResearch Example Chapter 1C Augustina S Fellazar100% (1)

- Lesson 5 Core Elements Evidenced Based Gerontological Nursing PracticeDokument38 SeitenLesson 5 Core Elements Evidenced Based Gerontological Nursing PracticeSam GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cast and SplintsDokument58 SeitenCast and SplintsSulabh Shrestha100% (2)

- Mapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthDokument23 SeitenMapeh: Music - Arts - Physical Education - HealthExtremelydarkness100% (1)

- Complications and Failures of ImplantsDokument35 SeitenComplications and Failures of ImplantssavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ironfang Invasion - Players GuideDokument12 SeitenIronfang Invasion - Players GuideThomas McDonaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles - of - Genetics 6th Ed by Snustad - 20 (PDF - Io) (PDF - Io) - 12-14-1-2Dokument2 SeitenPrinciples - of - Genetics 6th Ed by Snustad - 20 (PDF - Io) (PDF - Io) - 12-14-1-2Ayu JumainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abnormal Psychology Final Practice QuestionsDokument16 SeitenAbnormal Psychology Final Practice QuestionsJames WilkesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Five Elements Chart TableDokument7 SeitenFive Elements Chart TablePawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Operator MGC Ultima PFX - English - 142152-001rCDokument65 SeitenOperator MGC Ultima PFX - English - 142152-001rCEvangelosNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicDokument19 SeitenThe Effects of The Concept of Minimalism On Today S Architecture Expectations After Covid 19 PandemicYena ParkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supplement Guide Memory FocusDokument41 SeitenSupplement Guide Memory Focusgogov.digitalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information On The Use of Domperidone To Increase Milk Production in Lactating WomenDokument3 SeitenInformation On The Use of Domperidone To Increase Milk Production in Lactating WomenKhairul HananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biology Viral DiseasesDokument11 SeitenBiology Viral DiseasesPrasoon Singh RajputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nail Disorder and DiseasesDokument33 SeitenNail Disorder and Diseasesleny90941Noch keine Bewertungen

- Quantifying The Health Economic Value AsDokument1 SeiteQuantifying The Health Economic Value AsMatiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cholecystitis BelgradeDokument52 SeitenCholecystitis BelgradeLazar VučetićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab Exercise 5Dokument3 SeitenLab Exercise 5Yeong-Ja KwonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Illness in The NewbornDokument34 SeitenIllness in The NewbornVivian Jean TapayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016Dokument46 SeitenChemo Stability Chart AtoK 1jun2016arfitaaaaNoch keine Bewertungen

- LP MAPEH 9 (Health)Dokument4 SeitenLP MAPEH 9 (Health)Delima Ninian100% (2)

- Parathyroi D HormoneDokument25 SeitenParathyroi D HormoneChatie PipitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Perio QuestionsDokument32 SeitenPerio QuestionsSoha Jan KhuhawarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Ten Step Management of Severe MalnutritionDokument4 SeitenWho Ten Step Management of Severe MalnutritionShely Karma Astuti33% (3)

- Hemorrhoid - Pathophysiology and Surgical ManagementA LiteratureDokument7 SeitenHemorrhoid - Pathophysiology and Surgical ManagementA LiteratureIndra YaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Effect of Tobacco Smoking Among Third Year Student Nurse in The University of LuzonDokument6 SeitenThe Effect of Tobacco Smoking Among Third Year Student Nurse in The University of LuzonNeil Christian TadzNoch keine Bewertungen