Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Behavior Therapy

Hochgeladen von

Roci ArceOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Behavior Therapy

Hochgeladen von

Roci ArceCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

214

Behavior Therapy

5. Beutler LE, Engle D, Mohr D, et al: Predictors of differential response to cognitive, experiential and self-directed psychotherapeutic procedures. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:333-340, 1991. 6. Dobson K: A meta-analysis of the efficacy of cognitive therapy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 57:414419, 1989. 7. Elkins I, Shea T, Watkins J, et al: National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program. Arch Gen Psychiatry 46:971-982, 1989. 8. Evans M, Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, et al: Differential relapse following cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:774-78 1, 1992. 9. Fennel1 MJ: Depression. In Hawton K, Salkovskis PM, Kirk J, Clark DM (eds): Cognitive Behavior Therapy for Psychiatric Problems. A Practical Guide. New York, Oxford University Press, 1989, pp 169-234. 10. Hollon SD, Beck AT: Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In Bergin AE, Garfield SL (eds): Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1994, pp 428466. 1 I . Hollon SD, DeRubeis RJ, Evans MD, et al: Cognitive therapy and pharmacotherapy for depression: Singly and in combination. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:774-781, 1992. 12. Hollon SD, Shelton RC, Loosen PT: Cognitive therapy and pharmacothei-apy for depression. J Consult Clin Psychol 59:88-99, 1991. 13. Thase ME, Beck AT: Overview of cognitive therapy. In Wright JG, Thase ME, Beck AT, Ludgate JW (eds): Cognitive Therapy with Inpatients. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp 3-34.

42. BEHAVIOR THERAPY

Carry Welch, Ph.D., and Jacqueline A. Samson, Ph.D.

1. What is behavior therapy? Behavior therapy is a scientifically based approach to the understanding and treatment of human problems. It arose from laboratory experiments of animal behavior conducted in the early 1900s and has developed since from a large body of clinical research and experience. The goals of behavior therapy are: Enhance relationships Improve daily functioning Maximize human potential Reduce emotional distress Behavior therapy first came into common use in the 1960s and is now applied to a wide range of human problems. Originally the emphasis was on overt, measurable behavior and the application of classical and operant conditioning principles. However, since the 1980s it has been expanded to include cognitive aspects that emphasize the role of inner mental processes and emotional states. In addition, a new consideration of the broader social context of behavior has developed. The current focus of behavior therapy is not only what we overtly do, but also what we think and feel; all of these elements are influenced by the fundamental principles of learning.

2. Which patients are most likely to benefit from behavior therapy? Behavior therapy has been proven effective for the treatment of specific health problems requiring behavior change, such as smoking cessation, weight loss, stress, and pain management. In addition, treatment protocols for anxiety disorders and phobias such as obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), agoraphobia, and panic disorder show success equivalent to or exceeding medication alone. Behavior therapy and token economy systems (see Question 15) have been used with good outcome in patients with developmental disabilities and severely disturbed psychotic patients. It is the treatment of choice for severely ill patients who cannot participate in standard insight-oriented or cognitive therapies.

3. How do operant and classical conditioning differ?

Behavior therapy draws heavily on principles derived from classical (or Pavlovian) and operant (or instrumental) conditioning. Both forms of conditioning are important influences in daily life

Behavior Therapy

215

because they permit a rapid behavioral response and adaptation to inner changes and external events. Learning may occur through personal experience or the experience of others (i.e., through vicarious learning and modeling). Classically conditioned reflexes generally function to maintain internal bodily processes, and the conditioned responses that arise from this conditioning are stereotypic. Operant behaviors, on the other hand, are typically instrumental in managing the external environment. They involve skeletal muscles under voluntary control and the ongoing learning of a changing repertoire of new and varied behaviors.

4. Describe classical conditioning. Classical conditioning involves the acquisition of new cues (or triggers) to wired-in physiologic reflexes. These reflexes, which function naturally to protect us and to maintain our inner physiologic state, are principally linked to the autonomic nervous system. They are found in many internal bodily systems and are triggered by specific, unconditioned stimuli. For example, a nauseavomiting reflex typically occurs in response to the eating of overly rich, diseased, or poisonous food. This reflex helps to protect us from sickness. Classical conditioning occurs when a neutral stimulus that normally does not evoke a given reflex is paired repeatedly with the unconditioned stimulus that naturally provokes the reflex. Under such conditions, the neutral stimulus takes on the ability to evoke the reflex. For example, the nausea reflex in response to eating rich or poisonous food can become linked to the sight or smell of the food (or even just the thought of it). Cancer patients, who experience nausea and sickness as side effects of chemotherapy treatment, may develop anticipatory nausea on entering the hospital for treatment. Both responses to a previously neutral stimuli result from classical conditioning. 5. Give examples of classically conditionable reflexes. Many potential reflexes in the reproductive, muscular, respiratory, and circulatory systems can be classically conditioned. Note that the emotional components of reflexes (e.g., fear, pleasure, anxiety) can be conditioned as well as the physical components. In daily life, classical conditioning can be adaptive (e.g., it helps us learn quickly to avoid danger or unpleasantness) or maladaptive. For example, the normal adult response of sexual arousal and pleasant feelings with genital stimulation can become classically conditioned to inappropriate cues such as children (as in pedophilia) or nonanimate objects (as in fetishism).

Examules of Internal Reflexes and Conditioned Stimuli

Digestive system Vomiting and nausea in response to food poisoning (e.g., nausea on sight or smell of target food) Reproductive system Sexual arousal and pleasurable feelings in response to genital stimulation (e.g., arousal on viewing erotic books or videos) Respiratory system Asthma attack in response to allergens (e.g., an asthma patient feels the beginning of an attack on seeing an allergy-producing cat enter the room) Circulatory system Pounding heartbeat and anxiety produced by involvement in an auto accident on the freeway (subsequent fear and anxiety when driving in similar circumstances) Muscular system Relaxation response to ingestion of alcohol (relaxation felt on pouring the first drink at home at the end of a tense day)

6. Describe important principles of classical conditioning that are used in behavior therapy. Extinguishing occurs when the conditioned stimulus is not subsequently paired with the original unconditioned stimulus; the classically conditioned response weakens and becomes less frequent. Generalization occurs when similar stimuli evoke a similar conditioned response. For example, a child frightened by the harking of a large dog may develop an anxious, fearful response to all dogs.

216

Behavior Therapy

Discrimination occurs when the individual learns to respond differently to two similar or related stimuli. For example, the child frightened of dogs may subsequently learn that large dogs that bark aggressively are more dangerous than small, quiet dogs. Counter-conditioning occurs when a conditioned stimulus is paired with a new stimulus that produces an incompatible or opposite response. The original, problematic conditioned response is extinguished by this technique, and new, healthy conditioning is introduced simultaneously. For example, a patient with a spider phobia can be taught relaxation techniques and then in therapy be asked to recreate the relaxed feeling during simultaneous exposure to the anxiety-provoking spider stimulus. Under such conditions, the old conditioned anxiety response to spiders weakens. Aversive counter-conditioningis used to reduce problematic behaviors that are pleasurable. For example, an alcoholic patient may be given disulfiram (Antabuse) so that drinking alcohol becomes associated with nausea and unpleasantness, thereby helping to reduce the frequency of later drinking. Covert conditioning is classical conditioning that occurs through imagery techniques rather than actual (in vivo) experience.

7. Describe operant conditioning and its important principles. Consequences shape and modify behavior in operant conditioning (also known as trial-anderror learning). Behavior that produces good effects becomes more frequent (positive reinforcement occurs), whereas behavior that produces bad effects becomes less frequent (negative reinforcement occurs). Learning occurs when the consequences are contingent (interpreted to be causally linked) on the operant behavior. Situational, antecedent cues influence behavior in operant conditioning; any given operant behavior may produce good effects in one situation but bad effects in another. Thus we learn to discriminate between situations in which behavior may be rewarded or punished. For example, stepping on the gas pedal when driving a car produces good effects when traffic lights are green (the driver can proceed quickly with the intended journey) but bad effects when they are red (the driver may receive a speeding ticket or have a serious accident). Shaping occurs when new, complex behaviors are learned through reinforcement of successive approximations of the desired goal behavior. Discrimination occurs when an individual learns to respond differently to two similar predictive cues through differential reinforcement (i.e., one predicts reinforcement and the other does not, or one predicts more reinforcement than the other). For example, a shopper may drive to store A rather store B because he or she has learned that store A has better bargains. Generalization occurs when stimuli that resemble a predictive cue become cues to the operant behavior. For example, a child who learns to bang in a nail with a hammer may then enjoy hammering many objects that look like a nail. Understanding important situational cues and the negative or positive consequences of behavior are the two keys to understanding how operant behavior arises and is subsequently maintained, shaped, or extinguished.

8. Describe systematic desensitization. Systematic desensitization, which is used principally in the treatment of phobias and OCD, combines counter-conditioningwith extinction. It can be carried out through patient imagination or (more effectively) in vivo. This approach reduces the conditioned anxiety response by pairing incompatible, positive feelings (e.g., relaxation, calm) with the original anxiety-provoking, conditioned stimulus. The patient first learns relaxation techniques. Then a hierarchy of anxiety-provoking situations is identified by the therapist and patient to guide treatment planning. The patient is taught to rate the conditioned anxiety he or she feels on a scale from 0 (e.g., no fear or anxiety) to 10 (e.g., extreme fear, panic) to provide immediate feedback during each treatment exercise. Then, in therapy and in homework, the patient is systematically exposed to graded levels of conditioned anxiety through imagination or in vivo. At each anxiety-provoking level, the patient pairs relaxed feelings and

Behavior Therapy

217

thoughts with the conditioned stimulus and endures the conditioned stimulus until the anxiety subsides to a low level. For example, a patient with a fear of flying may work through a hierarchy of fears by going through airport procedures before a flight, sitting in a plane, taking off, and then finally flying and landing. This process often is preceded by practice sessions in the office in which each phase is imagined along with a paired relaxation exercise. The aim of treatment is for the patient to feel little anxiety in the most difficult flying-related situations. Research has shown that the relaxation component of systematic desensitization is not always necessary for successful treatment.

9. Describe the use of exposure with response prevention in the treatment of simple phobias. In this method, the conditioned anxiety reaction is extinguished through enduring exposure to the feared phobic object. This strategy is combined with prevention of usual escape (avoidance) behaviors that provided reinforcement in the past through negative reward (i.e., relief from phobic anxiety). For example, if a patient with a spider phobia is exposed to pictures or thoughts of spiders without escape or avoidance, he or she will experience a gradual reduction of anxiety and fear as the presence of the unconditioned stimulus (the spider) persists. In therapy, patients are taught the rationale behind the treatment, receive specific exposure with response prevention treatments, practice homework assignments at fixed times, discuss homework with the therapist, receive new assignments, and carry out maintenance exercises in follow-ups if needed. For simple phobias, exposure in vivo is generally preferred to exposure through imagination of the phobic object. Exposure and cognitive restructuring approaches (used to overcome irrational fears and negative thoughts) have become the psychosocial treatments of choice for panic, agoraphobia, and social phobia (see Chapters 14 and 15).

10. Name the essential elements of behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsivedisorder. Behavioral assessment identifies the nature of obsessional thoughts and compulsive rituals as well as related fear and anxiety responses. Gradual exposure in vivo to the problematic conditioned stimuli (e.g., exposure to dirty objects for patients with fears of dirt and contamination) is based on a hierarchy drawn up by the patient and therapist. This exposure allows extinction of the conditioned anxiety response. Response prevention is applied to obsessive rituals (e.g., compulsive hand-washing behaviors) used by the patient to alleviate anxiety after exposure to the feared situation. Faulty patient cognitions (self-talk) are identified. Ongoing structured homework includes further exposure and response prevention assignments and correction of maladaptive self-talk. 11. Describe flooding. In flooding, patients are exposed in vivo or through imagination to their conditioned object of fear at the most anxiety-provoking level possible until the fear and anxiety responses have been extinguished. Flooding differs from systematic desensitization, in which graded levels of exposure are introduced. Furthermore, in flooding the therapist controls the exposure, whereas in systematic desensitization the patient determines progression through the hierarchy of conditioned fears. Flooding may be poorly tolerated by some patients because of the high level of unpleasant feelings. In vivo flooding generally is considered more effective than flooding through imagination. 12. What is the Premack principle? If, as a precondition made in therapy, the patient must complete desired low-frequency behavior before high-frequency behavior can be carried out, the desired behavior will increase in frequency. For example, if an obese patient in behavior therapy for weight control contracts to complete a 20-minute walk each evening before sitting down to watch a favorite television show (something the patient does often), regular walking will increase in frequency and weight loss and health gains will be more likely to occur. The high-frequency behavior typically is pleasurable and provides positive reinforcement for the low-frequency behaviors. This principle is applied in many forms of behavior therapy.

218

Behavior Therapy

13. What is the role of cognitive factors in behavior therapy? An understanding of the role of cognitive factors in the development and maintenance of problem behaviors enables the therapist to identify cognitive distortions (negative self-talk and beliefs) arising from false assumptions or interpretations of life experiences and fear-inducing self-instructions. Cognitive interventions aim to teach the patient to recognize distortions of thinking and to replace them with more realistic, positive thoughts. They are particularly helpful in the treatment of anticipatory anxiety, demoralization, avoidance behaviors, and low self-esteem (see Chapter 41).

14. What is assertiveness training? Assertiveness training uses principles of operant reinforcement to improve social skills through shaping, modeling of appropriate social behaviors by the therapist, role rehearsal of new skills in therapy sessions, and patient homework assignments. Typical problems include poor refusal skills; difficulties with self-disclosure, expression of negative emotions, and giving or receiving criticism; and opening, maintaining, and closing conversations. Such deficits can be incorporated into a broader treatment plan for the presenting clinical problem. Treatment begins with a careful recording of the problematic social situations and the circumstances under which problem behaviors and thoughts arise. Patients are taught new social responses for each specific problematic social situation. Problem solving is used in reviews of patient homework exercises, and new goals are set as the patient progresses to more challenging social situations based on a previously agreed hierarchy of social difficulty. Mastery of problem situations may combine with newfound enjoyment of social activities to reinforce new behaviors through positive reward.

15. Describe token economies and their use. Token economies are based on the operant conditioning principle that positive reward of a desired behavior increases its frequency. They often involve the use of behavior shaping (i.e., the selective reinforcement of successive approximations to the target behavior). All token economies have in common a clear definition of the appropriate behavior that the therapist wishes to promote and a contract with the patient that details the explicit rewards for carrying out desirable behaviors. Target behaviors may range from simple tasks related to feeding, personal hygiene, or politeness to complex social interaction behaviors that are the end result of a systematic behavior-shaping schedule. Token economies may be based on the use of primary reinforcers (e.g., food, drink) or secondary (acquired) reinforcers (e.g., tokens, points, praise, smiles). Tokens or points are accumulated by the patient and exchanged for tangibles such as television time, toys, or privileges. Points or tokens also may be taken away for inappropriate behavior (negative punishment). Note that some primary reinforcers, such as food (e.g., candy), may be problematic as they can reach levels of satiation, whereas secondary rewards (e.g., tokens) cannot. Token economies have been used to promote adaptive, normal, or healthy behaviors in classrooms, adult day hospitals, sheltered workshops, and patient psychiatric settings; to help family functioning; and to promote individual self-development.

16. What is stimulus control? Large numbers of stimuli from the environment and from within our bodies influence behavioral responses in any given situation at a given point in time. Depending on past learning, significant stimuli may be (1 ) unconditioned or conditioned stimuli that produce classical responses, (2) discriminant stimuli that predict operant responses, or (3) stimuli that operate in both capacities. Treatment approaches based on stimulus control involve the identification of this array of antecedent stimuli through a careful behavioral assessment and implementation of strategies to limit their influence. Stimulus control approaches have been used notably in the management of obesity and smoking cessation. For example, obese patients are taught to recognize conditioned stimuli (from previous classical learning) and predictive stimuli (from previous operant learning) that may promote eating when the patient is not hungry. A patient who eats when depressed, bored, or angry is taught to recognize these cues and is instructed to carry out healthier, incompatible behavior instead (e.g., go for a walk, phone a friend). Food can be hidden from view outside of mealtimes, and eating can be restricted to

Behavior Therapy

219

the dining table only (instead of while watching television or reading). The patient may be given specific exercises to slow down the rate of eating and to increase awareness of consumption. A slower eating speed with improved awareness of the pleasurable, hedonic value of food may reduce overall calorie intake. In addition, slower eating is thought to give the brain sufficient time to respond appropriately to rising blood glucose levels that provide feedback signals of satiety.

17. How does biofeedback work? Biofeedback involves the use of specific machines that provide information (feedback) about variations in one or more of the patients physiologic processes that are not ordinarily perceived (i.e., brain wave activity, muscle tension, blood pressure). Feedback over a period of time may help the patient to learn to control certain target physiologic processes (i.e., anxiety, muscle tension responses) through operant conditioning. For example, awareness of alpha wave patterns through a graphic representation of wave activity on a biofeedback monitor may help the patient to elicit a relaxation response (see Chapter 46).

18. How is behavior therapy structured?

The foundation of behavior therapy is the initial behavior analysis, a process of careful documentation and recording of the specific conditions under which presenting problem behaviors arose and are maintained. Based on the behavioral analysis, a specific series of treatment tasks devised by the therapist and patient are implemented in therapy sessions and in regular patient homework. Because behavior therapy is highly goal-oriented, treatment goals are clearly spelled out for the patient, progress is assessed and discussed, and new goals are set for the next stage of treatment. Treatment gains are maintained with follow-up sessions and ongoing homework assignments. Through this process, behavior therapy reshapes the problem behavior in a more desirable direction. The treatment plan may include a microanalysis that focuses on the conditions surrounding the presenting clinical problem and a macroanalysis that relates the presenting problem to other broader problem areas (e.g., social skill deficits, marital problems).

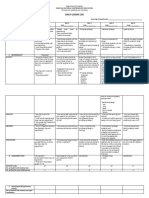

19. What differentiates behavior therapy from psychodynamic therapy?

Behavior Therapy

FOCUS

Psychodvnamic Therauv

Historical and early life experiences, parenting dynamics, enduring personality traits; links between these and current life experiences and problematic emotions and behaviors Reshape the intrapsychic structure of the patient to produce favorable symptom change based on specific theories about the nature of early childhood nurturance experiences and parenting dynamics Unstructured approach facilitates unexpected associations and derives new information and insights into the causes of current problems

Conditions surrounding current problematic behavior and past circumstances that may highlight maladaptive learning relevant to the current problems Improve problematic behaviors, cognitions, and emotions directly, through application of principles of classical and operant learning theory and cogni tive therapy Highly structured and goal- and outcomeoriented

GOAL

STRUCTURE

Although behavioral and psychodynamic therapies differ markedly in theoretical basis and treatment approach, elements of each may be found in the other. Information gathering is important in both, as part of the continual exploration for new ideas and connections. Repeated discussion of anxiety-producing concerns in the comfortable environment of psychodynamic therapy sessions may lead to extinction of a conditioned anxiety response (as in systematic desensitization). In behavior therapy, open-minded questions and chance discussions in unstructured parts of a treatment

220

Planned Brief Psychotherapy

session may lead to important insights into the broader psychosocial context of specific problematic behaviors (e.g., the presence of marital or work difficulties that exacerbate problem behaviors). BIBLIOGRAPHY

I . Baldwin JD, Baldwin J: Behavior Principles in Everyday Life. Englewood Cliffs, NJ, Prentice-Hall, 1981. 2. Emmelkamp PMG: Behavior therapy with adults. In Bergin AE, Garfield SL (eds): Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 4th ed. New York, John Wiley and Sons, 1994, pp 377427. 3. Emmelkamp PMG, Bourman TK, Scholing A: Anxiety Disorders. A Practitioners Guide. Chichester, John Wiley & Sons, 1992. 4. Griest JH: Behavior therapy for obsessive compulsive disorders. J Clin Psycho1 55:60-68, 1994. 5. Noyes R: Treatments of choice for anxiety disorders. In Coryell W, Winokur G (eds): The Clinical Management of Anxiety Disorders. New York, Oxford University Press, 1991. 6. Sloane R, Staples F, Cristol A, et al: Psychotherapy Versus Behavior Therapy. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 1975. 7. Wachtel P: Psychoanalysis and Behavior Therapy. New York, Basic Books, 1977.

43. PLANNED BRIEF PSYCHOTHERAPY

Mark A. Blais, Psy.D.

1. What is the natural course of psychotherapy? Despite the common perception that psychotherapy is a long-term, even timeless, enterprise, most of the existing data indicate that psychotherapy as it is practiced in the real world is a time-limited process. National outpatient psychotherapy utilization data from 1987 (obtained before the nationwide impact of managed care) reveals that 70% of psychotherapy users received 10 or fewer sessions, and only 15% received 21 or more sessions.I8 These data are highly consistent with findings from other utilizations studies. Clearly, most patients have a time-limited or brief psychotherapy experience. This chapter will help you deliver psychotherapy in an organized, planned, and thoughtful manner that more closely matches the natural course of psychotherapy.

2. How did brief psychotherapy develop?

Freud was one of the first practitioners of brief psychotherapy. A review of his early cases reveals that he treated many patients in a span of weeks to months rather than years. Over time, as psychoanalytic theory became more complex, the goals of psychoanalysis became more ambitious, and the length of treatment increased greatly. As early as 1925 this trend had become a concern to some. Alexander and French can be considered the true fathers of brief psychotherapy. Their book Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy outlined the first systematic attempt to develop a shorter and more efficient form of psychotherapy. Although not generally accepted in its time, this work laid the foundation for both psychoanalytic psychotherapy and modem brief psychotherapy. The modern era of brief treatment began with the work of Malan and of Sifneos. At present, brief psychoanalytic psychotherapies are supplemented by several other time-limited treatments, such as Becks cognitive therapy, Manns existential psychotherapy, and Klermans interpersonal treatment of depression.

3. How does brief psychotherapy differ from long-term psychotherapy? Four dimensions, considered common to all brief therapies, differentiate short-term from the more traditional long-term therapies: (1) the setting of a fixed time limit for the treatment, (2) holding to specific patient selection criteria, ( 3 ) using a treatment focus to limit the scope of the therapy, and (4) requiring increased activity by the therapist.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- I. Approach To Clinical Interviewing and DiagnosisDokument6 SeitenI. Approach To Clinical Interviewing and DiagnosisRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Antianxiety AgentsDokument4 SeitenAntianxiety AgentsRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Encopresis and EnuresisDokument10 SeitenEncopresis and EnuresisRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sedative-Hypnotic DrugsDokument8 SeitenSedative-Hypnotic DrugsRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mood-Stabilizing AgentsDokument9 SeitenMood-Stabilizing AgentsRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Planned Brief PsychotherapyDokument7 SeitenPlanned Brief PsychotherapyRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group TherapyDokument6 SeitenGroup TherapyRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- DeliriumDokument5 SeitenDeliriumRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- DementiaDokument6 SeitenDementiaRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impulse-Control DisordersDokument6 SeitenImpulse-Control DisordersRoci ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- North Luzon Philippines State College: Adal A Dekalidad, Dur-As Ti PanagbiagDokument1 SeiteNorth Luzon Philippines State College: Adal A Dekalidad, Dur-As Ti PanagbiagAdrian DoctoleroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Final Exam ReviewDokument11 SeitenFinal Exam ReviewArnel DimaanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Autism Summary of Evidence For Effective Interventions November 2019Dokument24 SeitenAutism Summary of Evidence For Effective Interventions November 2019JCI ANTIPOLONoch keine Bewertungen

- Involves Students Teaching Other Students. Peer Tutoring DividedDokument2 SeitenInvolves Students Teaching Other Students. Peer Tutoring DividedMitsy SumolangNoch keine Bewertungen

- LET ReviewerDokument22 SeitenLET ReviewerAnonymous 5CYvuGP5100% (7)

- Ali Hafizar Bin Mohamad Rawi: Prepared byDokument45 SeitenAli Hafizar Bin Mohamad Rawi: Prepared byAnonymous wsqFdcNoch keine Bewertungen

- ECT339 MODULE by Peter WafulaDokument105 SeitenECT339 MODULE by Peter WafulaStephen TinegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Process and Theories of LearningDokument32 SeitenThe Process and Theories of LearningRicha TiwariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ursin, H. (1998) The Psychology in PsychoneuroendocrinologyDokument16 SeitenUrsin, H. (1998) The Psychology in PsychoneuroendocrinologyCristian jimènezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Episode 4: Individual Differences and Learner's Interaction: An Observation Guide For The Learner's CharacteristicsDokument7 SeitenEpisode 4: Individual Differences and Learner's Interaction: An Observation Guide For The Learner's CharacteristicsHannahclaire Delacruz100% (1)

- DLLDokument15 SeitenDLLtracy carpio0% (1)

- University of Eastern Philippines: University Town, Northern SamarDokument5 SeitenUniversity of Eastern Philippines: University Town, Northern SamarJane MinNoch keine Bewertungen

- APA Handbook of Behavior AnalysisDokument6 SeitenAPA Handbook of Behavior AnalysisVũ Nam TrầnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of A Brief Staff Training Procedure On Instructors' Use of Incidental Teaching and Students' Frequency of Initiation Toward InstructorsDokument19 SeitenEffects of A Brief Staff Training Procedure On Instructors' Use of Incidental Teaching and Students' Frequency of Initiation Toward InstructorsIgorBaptistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CALLP Module 7Dokument11 SeitenCALLP Module 7Jasmin FajaritNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behavior - Prevention, Intervention, and De-Escalation Pt. 1Dokument14 SeitenBehavior - Prevention, Intervention, and De-Escalation Pt. 1Erika PetersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Single Subject Research Applications in Educational & Clinical Settings Stephen B RichardsDokument370 SeitenSingle Subject Research Applications in Educational & Clinical Settings Stephen B RichardsAlessandros AnckleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Toilet Training Children With Sensory Impairments in A Residential School SettlngDokument10 SeitenToilet Training Children With Sensory Impairments in A Residential School SettlngĐỗ Hoàng SơnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ch4 - Learning and Transfer of TrainingDokument58 SeitenCh4 - Learning and Transfer of Trainingreema8alothmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Challenges of Modular Distance LearningDokument8 SeitenChallenges of Modular Distance LearningIna100% (1)

- Students' BehaviorDokument19 SeitenStudents' Behaviorcrisselda chavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluency Young: Shaping Stutterers WithDokument10 SeitenFluency Young: Shaping Stutterers WithvbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tsl3109 PPG Module Managing The Primary Esl ClassroomDokument154 SeitenTsl3109 PPG Module Managing The Primary Esl ClassroomARINI100% (1)

- Abhishek Nandy, Manisha Biswas (Auth.) - Reinforcement Learning - With Open AI, TensorFlow and Keras Using Python-Apress (2018)Dokument174 SeitenAbhishek Nandy, Manisha Biswas (Auth.) - Reinforcement Learning - With Open AI, TensorFlow and Keras Using Python-Apress (2018)DineshKumarAzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Good Bird Magazine Vol4 Issue3Dokument92 SeitenGood Bird Magazine Vol4 Issue3mbee3Noch keine Bewertungen

- Behaviorism (Also Called Learning Perspective) Is A Philosophy ofDokument20 SeitenBehaviorism (Also Called Learning Perspective) Is A Philosophy ofARNOLDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Name: Amna Khalid Ba (Hons) 3 Year Subject: Early Childhood Special Education Department of Special EducationDokument5 SeitenName: Amna Khalid Ba (Hons) 3 Year Subject: Early Childhood Special Education Department of Special EducationKakaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PunctualityDokument11 SeitenPunctualityKristel Joy ManceraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Connecting Positive Psychology and Organizational Behavior ManagementDokument24 SeitenConnecting Positive Psychology and Organizational Behavior ManagementBarranuqilla me quedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Behaviorist PerspectiveDokument31 SeitenBehaviorist Perspectivegothic wontonNoch keine Bewertungen