Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Evidence Based Management

Hochgeladen von

solo_gauravOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Evidence Based Management

Hochgeladen von

solo_gauravCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Evidence Based Management: A Review Misti Walker Evidence Based Management: A Review 1

If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants. Sir Isaac Newton Evidence based medicine began receiving attention nearly a decade ago. Th e concept is simple enough. Practitioners should employ the most current, applic able research, or findings, in dealing with a patient's care. Since then, various fields including education and psychology have adopted this strategy, grounded i n scientific research(Rynes, 2007). Similarly, the business world has begun to a dopt its own version of this framework. Evidence based management (EBM) was larg ely introduced by Stanford University professors Jeffrey Pfeffer and Robert Sutt on in 2006, as a result of five years of research on the topic(Pfeffer, 2006). T he two men have also created a website devoted to the topic, www.evidence-basedm anagement.com. This management style encourages managers to make business decisi ons based on the most up-to-date, pertinent scientific research available. This framework seeks to align business practices with scientifically proven research. Although this idea is quite simple in theory, in practice it can prove troubles ome. Common roadblocks to an effective EBM strategy are: A reluctance to rely on scientific evidence over personal experience An effort to capitalize on one's str engths with little regard to evidence The tendency to cling to old ideals and do gmas The inability to escape hype and fads The inclination to merely copy compet itor best practices To illustrate, consider physicians make decisions based on evidence only 15% of the time. The remaining 85% of decisions are generally based on outdated knowled ge, previous experience, long-held but unproven views, and information gleaned f rom 2

vendors(Pfeffer, 2006). It is no wonder, then, that evidence based medicine is r apidly gaining ground in the medical field. Benefits and Limitations Less obviou s, however, is the reason why this concept has been so slow to catch on in busin ess. Pfeffer and Sutton (2006) claim that some of the reasons for the slow adopt ion are the inability to generalize results across industries and individual com panies, lack of consensus on who is truly an expert in the field, and research l imitations, namely, social sciences findings are less reliable than their scient ific counterparts. Another limitation is the lack of consensus on certain topics and the difficulty practitioners face in obtaining meaningful, timely research( Rynes, 2007). To illustrate, consider the research performed by Rynes, Giluk, an d Brown (2007) at the University of Iowa. The authors set out to determine what topics are being covered by scholarly and bridge journals and if the topics cove red were consistent with the best available research. In a systematic review of recent HR journals, the authors sought to explore the gap between research and p ractice in content areas such as personality in selection. The researchers found that some periodicals presented information in a wholly research-consistent way , but were limited in content and that some publications had both research-consi stent and research-inconsistent findings. Perhaps more troubling is the discover y that issues such as personality were not covered at all by some journals. The authors assert that the gap between what is being researched and reported also g oes the other way. In other words, issues that practitioners are interested in a re not being researched. 3

Learmonth (2006) goes further to add that because of the lack of consensus in th e field of management, practitioners that seek answers in journals are likely to be even more confused about the topic after reading conflicting viewpoints. Als o, any research that is done based on ideas not shared by everyone invariably be comes less reliable, the more it is expanded. Pretentious writing styles, common in scholarly journals, as well as the gap between what is being researched and what is being reported in the popular business press further compound the proble m. Not to mention, most scholarly journal articles are highly differentiated, fu rther exacerbating the problem of generalization. Some publishers of scholarly j ournals will not accept submissions that do not contribute something new, which leads to a greater reliance on niche subjects to satisfy these requirements. The authors (Rynes, 2007) suggest that the field of EBM could be advanced at a fast er rate if scholarly journals accepted succinct, wellcrafted articles that trans lated the often mundane, number intensive research. This disparity is directly l inked to the gap in managerial actions and scientific evidence. Perhaps a contri butor to the problem is that business schools rarely teach students to understan d or use evidence(Rousseau, 2007). It is no wonder, then, that these business sc hool graduates don't seek evidence on the job. Although EBM is not without its sha re of limitations, supporters would argue that the benefits greatly outweigh the costs. A discipline that is rooted in science and careful observation and has g arnered praise in fields such as medicine and education is bound to be beneficia l to business. EBM and Strategy Firms that embrace EBM make use of the extensive research that has been done on strategy what works and what doesn't. Also, EBM fi rms adopt and cultivate a 4

curious nature that encourages constant review of policy and strategy to see if they work and to search for improvements. In other words, companies that are ser ious about EBM should relentlessly seek new knowledge and insight from both insid e and outside their companies, to keep updating their assumptions, knowledge, an d skills (Pfeffer & Sutton, 2006, p. 65). Leaders of firms adopting EBM should be prepared to lose a degree of power as research findings replace their own viewp oint, in some instances. The authors also warn of half-truths and misperceptions that pervade the business arena. For instance, the resouce based view of the fi rm maintains that first movers in an industry develop skills and practices over time that place new entrants at a distinct disadvantage. However, Pfeffer and Su tton (2006) point out that the empirical evidence purported to support these bel iefs is actually inconclusive and the success stories used to bolster the claim ar e often untrue. Best Practices In order for firms to reap the benefits of EBM, Pfeffer and Sutto n (2006) recommend the following: Demand evidence Examine logic Treat the organi zation as an unfinished prototype Embrace the attitude of wisdom 5

In other words, firms should rely on facts, not assumptions, always be open to n ew ideas and never forget that it is not what you know, it is what you don't know that matters. Works Cited Learmonth, M. (2006). Is There Such a Thing as Evidence-Based Management?: A C ommentary on Rousseaus 2005 Presidential Address. Academy of Management Review , 31 (4), 1089-1091. 6

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Read MeDokument3 SeitenRead Mesolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

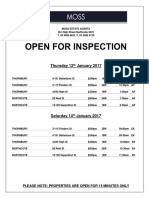

- Thursday 12 January 2017: Please Note: Properties Are Open For 15 Minutes OnlyDokument1 SeiteThursday 12 January 2017: Please Note: Properties Are Open For 15 Minutes Onlysolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- RporateDokument7 SeitenRporatesolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Debug RFC AbapDokument1 SeiteDebug RFC Abapsolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Example of Reflective Diary WritingDokument3 SeitenExample of Reflective Diary Writingsolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Debug RFC AbapDokument1 SeiteDebug RFC Abapsolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Had OopsDokument3 SeitenHad Oopssolo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- White Paper Application Performance Management (APM)Dokument26 SeitenWhite Paper Application Performance Management (APM)solo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Analysis On The Indian Renewable Energy Sector."feb 3,2012)Dokument3 SeitenComprehensive Analysis On The Indian Renewable Energy Sector."feb 3,2012)solo_gauravNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 21.JMM Promotion and Management, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsDokument3 Seiten21.JMM Promotion and Management, Inc. vs. Court of AppealsnathNoch keine Bewertungen

- UrethralstricturesDokument37 SeitenUrethralstricturesNinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dinup BSBMGT605Dokument41 SeitenDinup BSBMGT605fhc munna100% (1)

- SIPDokument2 SeitenSIPRowena Abdula BaronaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Interventions PDFDokument17 SeitenNutritional Interventions PDFLalit MittalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allocating Hospital Resources To Improve Patient ExperienceDokument6 SeitenAllocating Hospital Resources To Improve Patient ExperienceMichael0% (1)

- Module 5 Nature of The Clinical LaboratoryDokument26 SeitenModule 5 Nature of The Clinical LaboratoryAlexander LimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clothier-Wright2018 Article DysfunctionalVoidingTheImportaDokument14 SeitenClothier-Wright2018 Article DysfunctionalVoidingTheImportaMarcello PinheiroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Discursive StudiesDokument11 SeitenDiscursive StudiesSohag LTCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anti ParasiteDokument4 SeitenAnti ParasiteVörös Bálint100% (1)

- BotulismeDokument36 SeitenBotulismeDienjhe Love BunzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Training CourseDokument3 SeitenCommunity-Based Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Training CourseMARJORYL CLAISE GONZALESNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Myths and Truths About Transcendental MeditationDokument11 SeitenThe Myths and Truths About Transcendental MeditationMeditation Fix100% (2)

- Abdominal PainDokument39 SeitenAbdominal PainIsma Resti PratiwiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Infant Tub RationaleDokument4 SeitenInfant Tub RationaleAllen Kenneth PacisNoch keine Bewertungen

- COSWPDokument7 SeitenCOSWPjquanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Power Development Through Complex Training For The.3Dokument14 SeitenPower Development Through Complex Training For The.3PabloAñonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Professional Review Industry Route Guidance NotesDokument10 SeitenProfessional Review Industry Route Guidance NotesAnonymous TlYmhkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becky Ortiz ResumeDokument1 SeiteBecky Ortiz ResumeBecky OrtizNoch keine Bewertungen

- South Asian AnthropologistDokument8 SeitenSouth Asian AnthropologistVaishali AmbilkarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effects of Child Abuse and Neglect For Children and AdolescentsDokument15 SeitenEffects of Child Abuse and Neglect For Children and AdolescentsMaggie YungNoch keine Bewertungen

- XA6 - Emergency Provision Workbook 2020 v0 - 5 - CKDokument35 SeitenXA6 - Emergency Provision Workbook 2020 v0 - 5 - CKguyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingDokument6 SeitenGuidelines For Contemporary Air-Rotor StrippingGerman Cabrera DiazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding and Preparing For A CAtHeteRIZAtIon PRoCeDUReDokument7 SeitenUnderstanding and Preparing For A CAtHeteRIZAtIon PRoCeDUReBMTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book of Best Practices Trauma and The Role of Mental Health in Post-Conflict RecoveryDokument383 SeitenBook of Best Practices Trauma and The Role of Mental Health in Post-Conflict RecoveryDiego Salcedo AvilaNoch keine Bewertungen

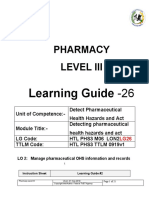

- Pharmacy Level Iii: Learning Guide - 26Dokument21 SeitenPharmacy Level Iii: Learning Guide - 26Belay KassahunNoch keine Bewertungen

- SES Presentation FinalDokument65 SeitenSES Presentation FinalCurtis YehNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 1007@s00068-mfjrbtDokument14 Seiten10 1007@s00068-mfjrbtJGunar VasquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key To Reading 3Dokument2 SeitenKey To Reading 3Thùy TrangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal - Register - Manufacturing Service (Aug '17) .Dokument8 SeitenLegal - Register - Manufacturing Service (Aug '17) .jagshishNoch keine Bewertungen