Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Powers and Priveleges of Advocates

Hochgeladen von

Peeyush KumarOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Powers and Priveleges of Advocates

Hochgeladen von

Peeyush KumarCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Powers and Privileges of an Advocate

Powers of an advocate

An advocate appearing in a case from the very nature of his duties and for the purpose of a proper conduct of the case must be deemed to have implied authority to admit or deny a document, to press or withdraw an issue in the case, to examine a witness or call no witnesses, and do such other acts as are required for the proper conduct of the case. 1. Abandonment of issues It may be taken as settled law that it is within the powers of a lawyer conducting a case to abandon or withdraw an issue which he thinks inadvisable to press. The reason for this rule is that without such powers no case could be tried without frequent adjournments and endless references to the parties. In Buta Ram v. Sayyad Mohammad, it was ruled that the general power of the advocate in the conduct of a suit includes the abandonment of the issues and in that case it was held that the plea which had been given up could not be revived later. Similarly, the giving up of a plea, raised in the plaint, by the advocate in the course of his statement recorded before the framing of issues for the purposes of clarifying points in dispute, is equally binding on the party concerned. This power of the advocate extends not only at the trial but also in appeal. A advocates general power in the conduct of an appeal include, in ordinary course, the abandonment of an issue which in his discretion he thinks inadvisable to press, and therefore, an issue of fact abandoned by him in the lower appellate Court cannot be challenged in second appeal. In fact the authority of an advocate extends to the limit of withdrawing a case of confessing a judgment if his doing so is for the benefit or advantage of his client even though he has no express authority from the client. Also, if an erroneous concession on the point of law has been made by the advocate in the trial Court, it does not disentitle the party to relief on that point in appeal. 2. Admission by the advocate A lawyer has authority to make admissions in Court on behalf of his client on matter of fact relevant to the issues in the case in which he is engaged. In a case, a letter was written by an advocate on behalf of his client. The exact amount due was not admitted in the letter, but it was nevertheless admitted that the goods had been purchased and not paid for in full and the letter ended with a definite promise to pay whatever might be found due before a certain date. It was held that the letter contained an acknowledgement of liability. It was further held in this case when a member of the Bar writes a letter purporting to be instructed by a client, it is to be presumed, until the contrary is proved, that the letter is written under instructions. In the ordinary course of his duties, an advocate may bind his client by admissions of fact provided that such admissions are made during the actual progress of litigation. Even where

admission made by an advocate in the course of a suit relates to collateral matter or where he gives up a doubtful claim which is not the subject-matter of the suit, there is a presumption that the advocate is acting under instructions if the admission or giving up the claim is for the benefit of the client. Where a consent decree is passed by a Court on the confession of judgement by a partys lawyer, it must be assumed that the Court must have satisfied itself before passing of the consent decree that the advocate confessing judgement had authority on behalf of the party to act in the manner in which he did. The challenging authority must prove to the contrary by positive evidence. But an advocate has no power to make an admission in a suit if he is instructed not to do so without express authority from his client. Where an admission on a point of fact is made under misapprehension, it is not binding on the client, and there is authority for the proposition that an erroneous admission made by an advocate may be allowed by the Court to be withdrawn. An advocate has authority to admit certain facts so as to dispense with the necessity of further proof in a criminal case at appellate stage. Parties are bound by admissions of advocate unless he has been induced or misled by some circumstances to make a statement under a mistake. The proposition of law seems to be well settled that wrong admission by a lawyer on a pure question of law is not binding on his client. Whether an admission is one of fact or of law will depend upon the circumstances of each case. The rule that a party is not bound by a wrong admission of law by his advocate applies with equal force whether such admission is made in the trial Court or in the Court of appeal. In a case, a doubt was expressed whether this doctrine extended to a case where to reopen the topic which was closed might entail the remanding of the case to the lower Court for a further finding of facts. An erroneous admission on a point of law by the advocate of a party in the trial Court cannot preclude him from claiming rights in the Appellate Court. In a case the cross-objection of the respondent arose from the decree of the Court of first instance and they were included in the grounds of appeal from the decree but were not pressed in the lower Appellate Court owing to a misapprehension by the advocate on a point of law. It was held that an erroneous admission by an advocate on a point of law was of no effect and did not preclude the party from claiming his legal right in Appellate Court. A concession by an advocate made in the lower Court that the compromise incorporated in a decree sought to be executed included certain matters not relating to the suit is not one on a pure question of fact but largely one of law by which the party is not bound in second appeal. It is true that an admission by an advocate on a point of law is not binding upon a party, but if on the basis of such an admission, a decree has been passed, the decree is binding upon the party unless it is set aside under the procedure prescribed by law. In other words, even though an admission may not be binding, a decision on the basis of that admission will bind the party.

While a mere admission on a point of law by advocate is not in itself binding either on the advocate or his client and it is open to him to retract or realize from it, there is nevertheless a well established principle of law that a litigant cannot through his advocate adopt an inconsistent position. A judgment given on the basis of admission is binding so long as it stands. If he desires to change his front, he should take some steps either to have the judgment vacated or at least to notify the opposite party that he proposes to question the validity of the judgment and to realize from the admission on the point of law made. If an advocate gives his consent to a decree on a misunderstanding that may be a good reason for the Court refusing to endorse the agreement. Where, however the advocate himself does not complain of having acted under a misapprehension or on a misunderstanding. If the client is negligent in the matter of giving instructions and if the advocate's exercise of judgment is not very sound, the agreement arrived at cannot be impeached on those grounds. Rankin, C.J., observed:

"If the party present in Court was not property and adequately consulted then his duty was to refuse, when the counsel was proposing to consent to the decree, to allow that to happen and if necessary to give notice to the other side and the Court that he was withdrawing the authority which the counsel had on his behalf. If any right is to accrue to the client from the fact of his being in Court, he must at least make his presence known to the counsel in order that the counsel may act accordingly, and it cannot be supposed that because he keeps quite and does not even instruct his counsel as to who the client is or take any step to inform the counsel of his presence, the counsel has got to carry on upon the footing that he has authority to deal with the case as circumstances may require." 3. Affidavit by an advocate - According to the well recognized practice which prevails wherever the members of the English Bar practice, the advocate should never file an affidavit in his professional capacity. An advocate who chooses to file an affidavit in support of a petition of appeal or revision must swear to the facts as they occur and take scrupulous care not to conceal or distort them or to confound them with his own impressions hastily formed at the moment, from the slip of notes found attached to the record of appeal or the refusal of the Judge to wail for the record before proceeding with the hearing or from his own failure to make an impression on the Judge, the advocate has no right to assume that the Judge had made up his mind or prejudged the case. 4. Reference to arbitration - An advocate engaged to act or plead in a suit does not possess the power to refer it to arbitration without express authority from the client. Such authority cannot be inferred by the mere circumstances, that the advocate though not formally appointed by a vakalat was allowed to sign a written statement. Where, however, an advocate is specifically authorized by his power-of-attorney to refer a suit to arbitration, he need not obtain express authority from his client before referring it to arbitration. In a case,

the suit was one for partition. On the motion of the lawyer of the parties, a particular person was appointed as a special referee to go into accounts and a consent decree was passed fixing the shares of the parties. Subsequently one of the parties appointed to the Court to set aside the decree on the ground that the advocate had agreement to arbitration against his instructions. The Court finding that the advocate has limited authority, set aside the decree and proceeded with the case. It was held by the High Court that if a client objected to important matters of account being referred to arbitration and to a private referee and if the reference was made by mistake of his advocate, the Court was perfectly justified in taking steps to see that the suit should proceed in the ordinary way. A lawyer is not competent to revoke the appointment of an arbitrator made by client and to appoint a new arbitrator in substitution without instruction from the client. 5. Offer to be bound by special oath - A party's agent binds the party by an agreement under Section 9 of the Indian Oaths Act, as much as a party himself. If a vakalat confers very wide powers in very general terms on the advocate, and authorized him to conduct the case and to take other proceedings and expressly states that whatever is done by the advocate should be accepted by the litigants and specifies particularly important powers like those of appointing arbitrators and compromising disputes, the power to abide by the statement of any witness whether under the Oaths Act or by way of an agreement of compromise is by necessary implication implied. It was further held in the case that an agreement to abide by the statement of a particular witness is in substance not a reference to arbitration. In Sadashiva Rayaji v. Vital, the Bombay High Court struck a different note in this respect. It supports the view that an agent holding power of attorney authorizing him to act and appear for a party to a suit, cannot bring the suit to a close by offering to be bound by the oath of the opposite party in a particular form, nor can an advocate bind his client and that under the Indian Oaths Act, 1873, no person but the party himself can make such an offer as is contemplated in Section 9. The power to abide by the statement of a witness is necessarily implied in the general authority given under the vakalat. Where a decree was passed on the basis of the statement of the witness who was a witness of the plaintiff's own choice, it was held that the plaintiff cannot realize from it on the ground that the Mukhtar Khas had exceeded the power given to him by agreeing to abide by the statement of the referee. As such, a vakalat gives sufficient authority to an advocate to argue, to make a reference under Section 9. But as pointed out by their Lordships of the Nagpur High Court advocates or other agents should in their own interests, be careful not to make offers to be bound down by special oath except in the presence of the party or an express written authority to that effect. 6. Power to compromise - The position as regards counsel's authority to compromise and settle his client's claim is stated in American Jurisprudence, Section 98, as under -

"The rule is almost universal that an attorney who is clothed with no other authority than that arising from his employment in that capacity has no implied power by virtue of his general retainer to compromise and settle his client's claim or cause of action, except in situations where he is confronted with an emergency and prompt action is necessary to protect the interests of the client and there is no opportunity for consultation with him, generally, unless such an emergency exists, either precedent as special authority from the client or subsequent ratification by him is essential in order that a compromise or settlement by an attorney shall be binding on his client." Obviously, therefore, if a litigation instructs his advocate not to compromise his case, his advocate is bound by such instructions even though he honestly believes that a compromise settlement would be to the best interest of his client. On the other hand, there can be no question but that an advocate may be specially authorized to enter into a compromise which will be binding on the client, though it has been held that an advocate employed to bring suit for damages or to settled by compromise is not authorized to compromise without first consulting his client, especially after suit has been started. Some cases hold that the authority of an advocate to compromise is presumed until the contrary is shown, at least it is not to be presumed that this was done, without lawful authority, and slight evidence in such a case may be sufficient to authorize the belief that he was clothed with all the powers he assumed to exercise. It has been held that a compromise settlement made in good faith by lawyer, when sanctioned by the Court in a decree, is binding upon the client. Statutes relative to the authority of an advocate touching the conduct of his clients cause of action have generally been held to effect no departure from the general rule that an advocate has no implied authority to compromise his clients claim. The general rule has been held to apply even thought the client may be a resident of a distant State or is a municipality or other Government body. The general rule stated is now followed by the English Courts, although the early tendency of these Courts was apparently to recognize such powers. In some States, the question as to the implied power of an advocate to agree to a compromise of his clients right of action out of Court appears to be an open one and in a few jurisdictions it has been held that an agreement of compromise by an advocate is binding on the client. In some cases this view finds support in a statute expressly providing that no action shall be maintained on a demand settled by a creditor or his advocate entrusted to collect it in full discharge of it, by the receipt of money or other valuable consideration, however small. In India, the judicial authority has been divided as regards the implied powers of an advocate to enter into a compromise on behalf of his client without special authorities in that respect. But so far as the lawyers were concerned the consensus of judicial opinion had

been that a lawyer in this country has the same implied authority to compromise as he has in England. A lawyer of the High Court when briefed on behalf of a party in a subordinate Court has the implied authority of his client to settle the suit. The power to compromise a suit is inherent in the position of a lawyer. A counsel has by virtue of his position as such ample power to settle a dispute point and a specific power to compromise is not necessary for the purpose. This is so even if he has been engaged to press an interlocutory application. The implied authority of advocate is not an appendage of office, a dignity added by the Courts to the status of advocate. It is implied in the interest of the client, to give the fullest beneficial effect to his employment of a lawyer. Secondly, the implied authority can always be countermanded by the express directions of the client. No counsel has actual authority to settle a case against the express instructions of his client. If he considers instructions contrary to the interest of his client his remedy is to return the brief. The Calcutta High Court in a case, has gone so far as to hold that a compromise effected by an advocate is valid and binding upon the parties even though it had been effected contrary to the express instructions of the client unless the prohibition had previously been communicated to the other side. The apparent authority of the advocate, however, is restricted to acts and admissions coram judice or in Court. Such acts and admissions out of Court do not bind the client unless in fact they are authorized by the client or by his agent duly authorized by the client in that behalf. A compromise, therefore, effected by advocate out of the Court, and not assented to by the client, is binding on the client, only if it is expressly authorized or subsequently ratified by the client or his agent. The power to compromise may be validly exercised by a lawyer who has been authorized only to appear. The absence of a power-of-attorney in such circumstances would be no more than an irregularity which would not affect the validity of the compromise and the decree passed upon it. It must, however, be remembered that the implied authority of a lawyer to enter into a compromise is limited to the action in which he has been engaged and does not extend to matters which are extraneous to the action or which are merely collateral to it. Privy Council came out with its pronouncement about the powers of a lawyer to compromise in the following words: It has been well established that a lawyer appointed under a usual power-of-attorney is not endowed with power or authority to compromise the suit he is thus retained to argue. However, Allahabad, Patna and later view of Madras High Court did not make any distinction between the different categories of the advocate as far as their implied general power to enter into a compromise on behalf of the client was concerned.

In Sheonandan Prasad Singh v. Abdul Fateh Muhammad, Privy Council also without specially mentioning the counsels duty held that advocate in India have the same implied authority to compromise the action as have counsels in the English Courts. According to a Full Bench decision of the Nagpur High Court advocate in this country have inherent power both to compromise claims and also to refer disputes in Court to arbitration without the authority or consent of the clients, unless their powers in this behalf have been expressly countermanded, and this whether the law requires written authority to act or plead or not. In this case it has been held that an express or explicit direction or power in the vakalat given to an advocate to conduct and defend a suit, which must mean to contest it, cannot be deemed to include a direction or power to compromise it.

Privileges of advocates 1. Exemption from personal service A practicing solicitor is exempt from the necessity of performing any personal service which would interfere with his duties as an officer of the Court. He has, therefore, been held to be exempted from acting as overseer of a parish, as a church warden, or as a rent collector by manorial custom. Solicitors, clerks, and legal executives in the employment of solicitors are ineligible for jury service in the High Court, the Crown Court and County Courts. Nor is a solicitor or his managing clerk bound to serve on a coroners Jury. 2. Freedom from arrest A solicitor, but not a solicitors clerk, while engaged in his professional duties in going to or coming from the place of trial on behalf of a client is privileged from arrest on civil process but not on criminal process or pursuant to a punitive committal. This privilege is the privilege of the Court, not the privilege of the litigant, and the Court, if it thinks proper, may have a litigant appearing before it arrested on a committal order. 3. Protection from defamatory actions - A solicitor acting as an advocate is not liable to an action for libel or slander i.e. words written or spoken by him in the course of a judicial hearing, however improper or even malicious his behavior may have been, such words being absolute privilege on grounds of public policy. The protection is not only from actions for defamation but from any action brought against a solicitor because of what was said or done at the hearing unless the action against the solicitor is brought i.e. an abuse of the process of the Court. The absolute privilege from defamation actions covers everything that is done from the inception of the proceedings onwards and extends to all pleadings and other documents brought into existence for the purpose of proceedings and starting with the writ or other document which institutes the proceedings. Communications between solicitor and client w.r.t. matters upon which the client is seeking professional advice are absolutely privileged provided the conversation is fairly referable to the relationship of solicitor and client. Where a communication is made by a solicitor in the course of his professional duties on his client's behalf, which, if made by the client, would have been protected by qualified privilege, a solicitor is entitled to a like protection. More v. Weaver, 1928(2) KB 520, CA, where it was held that a communication between solicitor and client was absolutely privileged. 4. Confidentiality of communications between solicitor and client - A solicitor cannot be compelled to disclose communications, whether oral or written, passing directly or indirectly between him and his client, or between him and a person who is communicating with him professionally with a view to becoming his client, for the purpose of giving or receiving legal professional advice if they are legitimate communications in the sense that they are not made in furtherance of fraud or crime. It is not necessary that legal proceedings

should be contemplated, but it is necessary that the solicitor should be consulted professionally and not merely as a friend having legal knowledge. A communication made by a client to his solicitor for the purpose of being repeated to the other side is not privileged if the solicitor's authority to compromise a case is in question. The effect of the privilege is that neither the client, nor the solicitor without his consent, can be compelled to disclose the communication in the course of legal proceedings. The privilege is the clients, not the solicitors, and accordingly the client may restrain the solicitor from making disclosure or may waive the privilege. Until the client has waived the privilege it is the solicitors duty, if he is requested to make disclosure, to claim the privilege. The fact that the solicitors services are given by way of legal advice and assistance or by way of legal aid does not affect any privilege arising out of the relationship of solicitor and, client, but a solicitor who has given or declined to give legal advice had assistance is not precluded by privilege from disclosing to a general committee information it may require to perform its functions. Likewise, a solicitor acting for a person in receipt of legal aid is not precluded from disclosing to a general committee or an area committee any information or from giving any opinion required to perform its functions and further, a solicitor so acting or selected to act has a duty to report to the general committee any abuse of legal aid and to report to circumstances in which he has refused to act or has given up a case. European community law recognizes the confidentiality of certain communications between lawyer and client, this protection is a corollary of the principles of the ECC treaty concerning freedom of establishment and freedom to provide services, and applies without distinction to any lawyer entitled to practice his profession in one of the member states. The protection of written communications is subject to two conditions: (1) that they are made for the purposes and in the interests of the clients rights of defence; and (2) that they emanate from independent lawyers, that is to say, lawyers who are not bound to the client by a relationship of employment. This is in contrast to the position in English law where no distinction is made, as regards confidentiality of communications generally, between the independent legal advisor and the salaried legal advisor acting as such. 5. Liability in tort A solicitor is personally liable in tort where from his conduct it is clear that he has made himself a party to the tort. A solicitor acting for a client disposing of property or any interest in property for money or moneys worth to a purchaser is liable to an action for damages by the purchaser or person deriving title under him for any loss sustained by reason of: (1) the concealment of any instrument or encumbrance material to the title; or (2) any claim made by a person order a pedigree on which the title depends and which was falsified in order to induce the purchaser to accept the title. The client is liable in similar circumstances. A solicitor instructed by a client to carry out a transaction to confer a benefit on an identified third person owes a duty to that person to use proper care in carrying out the

instructions, and if a breach of that duty causes loss, even purely financial loss, to the third person the solicitor will be liable in negligence to him. 6. Criminal liability A solicitor, like any other person entrusted with or having received property as agent for or on account of another person, may be criminally liable for theft, for obtaining property by deception or a pecuniary advantage by deception, for false accounting or suppression of documents, or for handling stolen goods. A solicitor who is liable in damages, by statutory provision, for concealing or falsifying matters of title to property to induce a purchaser to accept the title offered also commits an offence. Similarly, as solicitor commits an offence if he fraudulently procures alterations of the register of title kept at the hand registry or of any land or charge certificate. 7. Arrest: jury service Whilst going to, remaining at and retuning from Court when engaged on business there, barristers are immune from arrest on civil process. 8. Absolute privilege for defamatory statements No action will lie against counsel in respect of words uttered in the cause of any judicial proceeding, even if it is alleged that the words were uttered maliciously and without justification or even excuse and even if the words are irrelevant to every issue contested in the proceedings. The reason for his absolute privilege is not a desire to prevent actions from being brought against persons who have acted maliciously; it is to secure the freedom and independence of counsel and to protect persons who have acted innocently and bona fide the vexation of defending unmeritorious actions. The privilege covers everything spoken or written in the ordinary course of any proceeding before any Court or Tribunal recognized by law, including statements made in the course of preparing for the proceeding. It does not protect the separate publication of a speech containing defamatory matter. The privilege applies whether the action is framed in defamation or in some other course of action, such as malicious prosecution or conspiracy. It does not apply, however, to an action brought in respect of a malicious prosecution or arrest of an abuse of the process of the Court merely because one step in the conduct complained of involved the utterance of words in Court and where the utterance of those words is not the substance of the complaint. The privilege is not confined to counsel, but applies equally to judges, parties and witnesses, and to solicitors acting as advocates. The privilege of counsel extends to the client in the sense that the client cannot be sued in respect of defamatory statements made by counsel on the clients behalf. 9. Privilege of communications Confidential communications passing between a barrister and his professional or lay client for the purpose of requesting or giving legal advice, such as instructions to counsel and counsels advice, are privileged from disclosure. The Court, will not at the instance of a third party, compel the client and will not allow the barrister, to give

evidence of such communications when oral, and will not order discovery of them when written. The privilege is not confined to such communications as are made in the course of, or in anticipation of, litigation, but the communications must be made in a professional capacity; an opinion given by a barrister as a friend is not privilege from disclosure; and the communications must be of a confidential character. Pleadings and counsels endorsement on his brief are not confidential communications, but drafts of pleadings and other documents settled by counsel are privileged, as are observations and notes written by counsel on his instructions. The mere fact that counsel has been retained is not privileged. The privilege does not extend to communications made for the purpose of committing a fraud of crime. The privilege is the privilege of the client and not of the barrister or other professional advisor. It may be waived by the client, but never ceases unless waived by the client or his successors in title. Privilege is not waived by referring to a document in a pleading, affidavit or list of documents: but it is waived when a document is disclosed to the other party in the course of litigation, unless the other party has procured inspection of the document by fraud or, on inspections, realizes that he has been permitted to see the document only by reason of an obvious mistake. When privilege is waived by disclosure of a document before trial or by its use in cross-examination, the waiver relates only to the document itself; but, if a privileged document is adduced in evidence, the waiver extends to the transaction to which the evidence goes and to other documents relevant to that transaction. Where no waiver of privilege has taken place, an injunction may be granted to compel another party into whose hands a privileged document has come to deliver up the document and any copies or notices of it and not to disclose or make any use of any information contained in the document.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Chapter 11-Authority of Attorney: Power To Bind ClientDokument4 SeitenChapter 11-Authority of Attorney: Power To Bind ClientRommel P. AbasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civpro Reviewer MidtermsDokument20 SeitenCivpro Reviewer MidtermsDuke SucgangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes in Riano. Civil ProcedureDokument14 SeitenNotes in Riano. Civil ProceduretmaderazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lack of jurisdiction as ground for annulmentDokument3 SeitenLack of jurisdiction as ground for annulmentMaribel Nicole LopezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Answers To Midterms in Remedial Law ReviewDokument5 SeitenAnswers To Midterms in Remedial Law ReviewKarl Estacion IVNoch keine Bewertungen

- Setting A Side An Arbitral Award On Grounds of Effluxion of Time and PartialityDokument16 SeitenSetting A Side An Arbitral Award On Grounds of Effluxion of Time and PartialityLDC Online ResourcesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mga Di Pa TaposDokument6 SeitenMga Di Pa TaposAinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preliminary Remedy Guide for Provisional AttachmentDokument5 SeitenPreliminary Remedy Guide for Provisional AttachmentEdsel Ian S. FuentesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3s Civpro Doctrines-1Dokument21 Seiten3s Civpro Doctrines-1MK CCNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Ethics on Termination of Attorney-Client RelationshipDokument31 SeitenLegal Ethics on Termination of Attorney-Client RelationshipCouleen BicomongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pale - Quiz6Dokument3 SeitenPale - Quiz6PIKACHUCHIENoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter XiDokument7 SeitenChapter XiMAYRISH SANGALANGNoch keine Bewertungen

- For FinalsDokument3 SeitenFor FinalsMikkah FactorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spc Trinidad Gr190710 LucasvslucasDokument2 SeitenSpc Trinidad Gr190710 LucasvslucasAB TGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Lesson 8Dokument6 SeitenCivil Procedure Lesson 8SAMUKA HERMANNoch keine Bewertungen

- C. Jurisdiction Over The PartiesDokument92 SeitenC. Jurisdiction Over The PartiesRenalyn ParasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Doctrines: 1. Boston Equity Resources Inc., Vs Court of Appeals and Lolita G. Toledo G.R. NO. 173946Dokument51 SeitenCivil Procedure Doctrines: 1. Boston Equity Resources Inc., Vs Court of Appeals and Lolita G. Toledo G.R. NO. 173946Rey LacadenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure Doctrines: Jurisdiction and EstoppelDokument52 SeitenCivil Procedure Doctrines: Jurisdiction and Estoppel'Joshua Crisostomo'Noch keine Bewertungen

- LiabilitiesDokument3 SeitenLiabilitiesFatima SladjannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure DoctrinesDokument51 SeitenCivil Procedure DoctrinesEricha Joy GonadanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Law NotesDokument18 SeitenRemedial Law NotesIELTSNoch keine Bewertungen

- VENUE RULE REVIEWDokument7 SeitenVENUE RULE REVIEWDuke SucgangNoch keine Bewertungen

- American Cyanamid Co V Ethicon LTD (1975) 2 WLR 316 - HLDokument16 SeitenAmerican Cyanamid Co V Ethicon LTD (1975) 2 WLR 316 - HLIkem Isiekwena100% (4)

- Solatan v. Inocentes, AC No. 6504, August 9, 2005Dokument3 SeitenSolatan v. Inocentes, AC No. 6504, August 9, 2005Malagant EscuderoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Rules on Civil ProcedureDokument571 SeitenRevised Rules on Civil ProcedureCesar CañonasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- THIRD PARTY CLAIM DoctrineDokument2 SeitenTHIRD PARTY CLAIM DoctrineLevz LaVictoriaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ortiz v. JaculbeDokument6 SeitenOrtiz v. JaculbemisterdodiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Service Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaDokument3 SeitenService Specialists v. Sherriff of ManilaAnjNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ateneo Central Bar Operations 2007Dokument11 SeitenAteneo Central Bar Operations 2007Mike MaputolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candor Toward The Tribunal - The Florida BarDokument29 SeitenCandor Toward The Tribunal - The Florida BarNeil GillespieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sievert Vs CADokument3 SeitenSievert Vs CAPearl Deinne Ponce de LeonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Canon 12 Quick Reference GuideDokument12 SeitenCanon 12 Quick Reference GuidenchlrysNoch keine Bewertungen

- 30) Tan v. LapakDokument2 Seiten30) Tan v. LapakprincessF0717Noch keine Bewertungen

- ExamDokument12 SeitenExamCharline Rondina SabenorioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Court Jurisdiction Required for AttachmentDokument72 SeitenCourt Jurisdiction Required for AttachmentMarry SuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence (People vs. Canay)Dokument8 SeitenJurisprudence (People vs. Canay)jhaneh_blushNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 40 - 46Dokument3 SeitenCase 40 - 46ace lagurinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philip Yu Vs CA Nov 29, 2005Dokument2 SeitenPhilip Yu Vs CA Nov 29, 2005Alvin-Evelyn GuloyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Temporary InjunctionDokument7 SeitenTemporary InjunctionMd. Fahim Shahriar MozumderNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure 1 1st YearDokument476 SeitenCivil Procedure 1 1st YearMel Voltaire Borlado Crispolon100% (1)

- Acknowledgement: Sumit Kumar SumanDokument21 SeitenAcknowledgement: Sumit Kumar SumanSureshNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 237428Dokument19 SeitenG.R. No. 237428Quisha LeighNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2nd Ass - Leg CDokument5 Seiten2nd Ass - Leg CKaye RabadonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Macalalag - Vs-OmbudsmanDokument2 SeitenMacalalag - Vs-OmbudsmanJerik SolasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tolentino vs. LevisteDokument1 SeiteTolentino vs. LevisteTon Ton CananeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Six: Effect of Failure To PleadDokument4 SeitenChapter Six: Effect of Failure To PleadMadeline DizonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ethics Cheat NotesDokument2 SeitenEthics Cheat NotesMarianne DomingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law NotesDokument7 SeitenAdmin Law Notesanon_131421699Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Procedure DigestsDokument5 SeitenCivil Procedure DigestsJozele DalupangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tropical Homes v. VillaluzDokument2 SeitenTropical Homes v. VillaluzwuplawschoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Civil Appeals ExplainedDokument74 SeitenCivil Appeals ExplainedMD. SAMIM MOLLANoch keine Bewertungen

- Agustin v. Court of Appeals: W/N DNA testing is unreasonable searchDokument5 SeitenAgustin v. Court of Appeals: W/N DNA testing is unreasonable searchVilpa VillabasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brito, Sr. vs. DianalaDokument2 SeitenBrito, Sr. vs. DianalaPACNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allegations in Pleadings and Affirmative DefensesDokument5 SeitenAllegations in Pleadings and Affirmative DefensesJodel Cris BalitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 392 Malvar V Kraft FoodDokument2 Seiten392 Malvar V Kraft FoodMarvin De Leon100% (1)

- Professional Ethics - LienDokument6 SeitenProfessional Ethics - LienBenjamin Brian Ngonga100% (1)

- Atty Mangontawar Vs NPCDokument2 SeitenAtty Mangontawar Vs NPC1234567890Noch keine Bewertungen

- Republic vs. "G" Holdings, Inc. 475 SCRA 608, November 22, 2005Dokument10 SeitenRepublic vs. "G" Holdings, Inc. 475 SCRA 608, November 22, 2005carl dianneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Read ThisDokument27 SeitenRead ThisGi NoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Drafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawVon EverandDrafting Written Statements: An Essential Guide under Indian LawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Payment Receipt Payment Receipt: Electronically Generated, Does Not Require SignatureDokument1 SeitePayment Receipt Payment Receipt: Electronically Generated, Does Not Require SignaturePeeyush KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Limited Liability Partnership Act amended to strengthen complianceDokument11 SeitenLimited Liability Partnership Act amended to strengthen compliancesrrc trustNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uppsc 2022 Gs Question Paper 1 Set BDokument29 SeitenUppsc 2022 Gs Question Paper 1 Set BPeeyush KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uppsc 2022 Gs Set D Question PaperDokument28 SeitenUppsc 2022 Gs Set D Question PaperPeeyush KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals 180 SCRA 156, December 15, 1989Dokument7 SeitenPioneer Insurance & Surety Corporation vs. Court of Appeals 180 SCRA 156, December 15, 1989MarkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benjamin Gomez v. Enrico PalomarDokument11 SeitenBenjamin Gomez v. Enrico PalomarUlyung DiamanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- De La Rama v. Ledesma20210424-14-Lsj4dxDokument4 SeitenDe La Rama v. Ledesma20210424-14-Lsj4dxLi-an RodrigazoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Ruling on Loan Agreement Interest RateDokument9 SeitenSupreme Court Ruling on Loan Agreement Interest RateMonicaSumangaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Torts: Mbe Practice QuestionsDokument16 SeitenTorts: Mbe Practice Questionsnkolder84Noch keine Bewertungen

- Speed V CADokument17 SeitenSpeed V CAMp CasNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 161122Dokument1 SeiteG.R. No. 161122annaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CLT Realty Development Corporation vs. Phil-Ville Development and Housing Corporation, 752 SCRA 289, March 11, 2015Dokument37 SeitenCLT Realty Development Corporation vs. Phil-Ville Development and Housing Corporation, 752 SCRA 289, March 11, 2015Clarinda MerleNoch keine Bewertungen

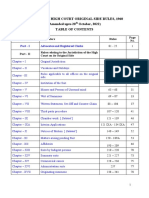

- BHC Original Side Rules, 1960Dokument661 SeitenBHC Original Side Rules, 1960Hamza LakdawalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 97-7957Dokument9 SeitenUnited States Court of Appeals, Second Circuit.: Docket No. 97-7957Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Effective Advocacy in Commercial ArbitrationDokument18 SeitenEffective Advocacy in Commercial ArbitrationIgor EllynNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11262014Dokument265 Seiten11262014Jaja GkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paul B. Weeks 2003 Exhibits 14-22Dokument60 SeitenPaul B. Weeks 2003 Exhibits 14-22Andrew KreigNoch keine Bewertungen

- Harry Palmer v. Eldon Braun, 376 F.3d 1254, 11th Cir. (2004)Dokument7 SeitenHarry Palmer v. Eldon Braun, 376 F.3d 1254, 11th Cir. (2004)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Digest - Uy Vs ContretasDokument2 SeitenCase Digest - Uy Vs ContretasMDR LutchavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- DisbarmentDokument62 SeitenDisbarmentTaco Belle100% (1)

- The Land Acquisition Act, 1894Dokument18 SeitenThe Land Acquisition Act, 1894Muhammad Sohail IrshadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calder Complaint Against Perls GalleryDokument8 SeitenCalder Complaint Against Perls GalleryartmarketmonitorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Land Law ProjectDokument21 SeitenLand Law ProjectNandesh vermaNoch keine Bewertungen

- in Re - Petition For Probate (Santiago)Dokument3 Seitenin Re - Petition For Probate (Santiago)Carie LawyerrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal Ethics Bar Exams 2015Dokument34 SeitenLegal Ethics Bar Exams 2015angela lindleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADokument8 SeitenAC.M THUKU & COMPANY ADVOCATESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adamson v. CA, GR No. 120935, May 21, 2009Dokument8 SeitenAdamson v. CA, GR No. 120935, May 21, 2009Henry LNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gosiaco vs Ching Civil Liability of Corporate Officers in Bouncing Check CasesDokument6 SeitenGosiaco vs Ching Civil Liability of Corporate Officers in Bouncing Check CaseskimuchosNoch keine Bewertungen

- GR No. 75042 (Republic v. IAC)Dokument3 SeitenGR No. 75042 (Republic v. IAC)Jillian AsdalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motion To DisqualifyDokument5 SeitenMotion To Disqualifyhimself2462Noch keine Bewertungen

- Carpo v. ChuaDokument5 SeitenCarpo v. ChuaBeltran KathNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legal and Judicial Ethics Case SummaryDokument300 SeitenLegal and Judicial Ethics Case SummaryHairan CadungogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Linda M. Ellis (Linda's Lyrics) vs. Eric J. Aronson & Dash Systems: Docket & ComplaintDokument71 SeitenLinda M. Ellis (Linda's Lyrics) vs. Eric J. Aronson & Dash Systems: Docket & ComplaintExtortionLetterInfo.comNoch keine Bewertungen