Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Kierkergaard Sickness Unto Death Excerpt

Hochgeladen von

aditya56Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Kierkergaard Sickness Unto Death Excerpt

Hochgeladen von

aditya56Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

DESPAIR IS THE SICKNESS UNTO DEATH This concept, the sickness unto death, must, however, be understood in a particular

way. Literally it means a sickness of which the end and the result are death. Therefore we use the expression fatal sickness as synonymous with the sickness unto death. In that sense, despair cannot be called the sickness unto death. Christianly understood, death itself is a passing into life. Thus, from a Christian point of view, no earthly, physical sickness is the sickness unto death, for death is indeed the end of the sickness, but death is not the end. If there is to be any question of a sickness unto death in the strictest sense, it must be a sickness of which the end is death and death is the end. This is precisely what despair is. But in another sense despair is even more definitely the sickness unto death. Literally speaking, there is not the slightest possibility that anyone will die from this sickness or that it will end in physical death. On the contrary, the torment of despair is precisely this inability to die. Thus it has more in common with the situation of a mortally ill person when he lies struggling with death and yet cannot die. Thus to be sick unto death is to be unable to die, yet not as if there were hope of life; no, the hopelessness is that there is not even the ultimate hope, death. When death is the greatest danger, we hope for life; but when we learn to know the even greater danger, we hope for death. When the danger is so great that death becomes the hope, then despair is the hopelessness of not even being able to die. It is in this last sense that despair is the sickness unto death, this tormenting contradiction, this sickness of the self, perpetually to be dying, to die and yet not die, to die death. For to die signifies that it is all over, but to die death means to experience dying, and if this is experienced for one single moment, one thereby experiences it forever. If a person were to die of despair as one dies of a sickness, then the eternal in him, the self, must be able to die in the same sense as the body dies of sickness. But this is impossible; the dying of despair continually converts itself into a living. The person in despair cannot die; no more than the dagger can slaughter thoughts can despair consume the eternal, the self at the root of despair, whose worm does not die and whose fire is not quenched. Nevertheless, despair is veritably a self-consuming, but an impotent self-consuming that cannot do what it wants to do. What it wants to do is to consume itself, something it cannot do, and this impotence is a new form of self-consuming, in which despair is once again unable to do what it wants to do, to consume itself; this is an intensification, or the law of intensification. This is the provocativeness or the cold fire in despair, this gnawing that burrows deeper and deeper in impotent self-consuming. The inability of despair to consume him is so remote from being any kind of comfort to the person in despair that it is the very opposite. This comfort is precisely the torment, is precisely what keeps the gnawing alive and keeps life in the gnawing, for it is precisely over this that he despairs (not as having despaired): that he cannot consume himself, cannot get rid of himself, cannot reduce himself to nothing. This is the formula for despair raised to a higher power, the rising fever in this sickness of the self.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- No and YesDokument1 SeiteNo and Yesaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Part 3 CompletedDokument1 SeitePart 3 Completedaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Derek Is A FreakDokument1 SeiteDerek Is A Freakaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- RashkDokument1 SeiteRashkaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Details of The Boo1Dokument1 SeiteDetails of The Boo1aditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Hi, Another ThingDokument1 SeiteHi, Another Thingaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wireless Communications and NetworksDokument1 SeiteWireless Communications and Networksaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4YEARDokument5 Seiten4YEARAbhinav AbhiNoch keine Bewertungen

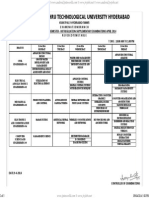

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument3 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aakhyan BrochureDokument48 SeitenAakhyan Brochureaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- B.tech. Regular Suppl. NotificationDokument8 SeitenB.tech. Regular Suppl. Notificationsheik1111Noch keine Bewertungen

- Academic Calendar For B.tech B.pharmacy 2012-2013 JWFILESDokument1 SeiteAcademic Calendar For B.tech B.pharmacy 2012-2013 JWFILESSandeep SunnyNoch keine Bewertungen

- B.tech B.pharmacy IV II AdvSupple Notification June2013Dokument6 SeitenB.tech B.pharmacy IV II AdvSupple Notification June2013aditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- 07a4bs02 Mathematics - IIIDokument8 Seiten07a4bs02 Mathematics - IIIaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Postponed Exam Re-SheduleDokument1 SeitePostponed Exam Re-Sheduleaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- JNTUH Credits Based Promotion Rules For Re-Admitted Students JWFILESDokument2 SeitenJNTUH Credits Based Promotion Rules For Re-Admitted Students JWFILESaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- IV Year II Sem-I Mid Term Exam Time TableDokument6 SeitenIV Year II Sem-I Mid Term Exam Time TableGanesh HydNoch keine Bewertungen

- III Year I Sem.r07Dokument4 SeitenIII Year I Sem.r07aditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- JNTUH Convocation Process JWFILESDokument0 SeitenJNTUH Convocation Process JWFILESkhajaimadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument3 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument5 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- JNTUH MODIFIED Rescheduled Dates of Postponed Exams 2013Dokument1 SeiteJNTUH MODIFIED Rescheduled Dates of Postponed Exams 2013aditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument3 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leaders in A Common Thought Matrix - The HinduDokument2 SeitenLeaders in A Common Thought Matrix - The Hinduaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- 08 06 2014 SundayHansSanjivaDevUpendranadhDokument1 Seite08 06 2014 SundayHansSanjivaDevUpendranadhaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument3 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- B.tech Regular Suppl Notification Nov-Dec 2013Dokument8 SeitenB.tech Regular Suppl Notification Nov-Dec 2013Anurag AllaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Acdemic Calendar 2014Dokument1 SeiteRevised Acdemic Calendar 2014aditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University HyderabadDokument4 SeitenJawaharlal Nehru Technological University Hyderabadaditya56Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- 2021 Digest of United States Practice in International Law and Narcotics TraffickingDokument849 Seiten2021 Digest of United States Practice in International Law and Narcotics TraffickingHarry the GreekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Srinivas Caste in Modern India and Other Essays PDFDokument101 SeitenSrinivas Caste in Modern India and Other Essays PDFjgvieira375178% (9)

- 2013 Timothy Dickeson Ielts High Score VocabularyDokument38 Seiten2013 Timothy Dickeson Ielts High Score Vocabularymaxman11094% (18)

- English 10: Quarter 1 - Module 1Dokument15 SeitenEnglish 10: Quarter 1 - Module 1margilyn ramosNoch keine Bewertungen

- DALLEY, Stephanie - Yahweh in Hamath in The 8th Century (1990)Dokument13 SeitenDALLEY, Stephanie - Yahweh in Hamath in The 8th Century (1990)pax_romana870100% (1)

- History of Haryana-FinalDokument120 SeitenHistory of Haryana-FinalVillage Wala RaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- JAIMINI ASTROLOGY - Calculation of Arudha - CS PATEL :A CASE STUDYDokument4 SeitenJAIMINI ASTROLOGY - Calculation of Arudha - CS PATEL :A CASE STUDYANTHONY WRITER0% (1)

- ResistanceDokument2 SeitenResistancewlewisiiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mrichchakatika - A Chronicle of Its MilieuDokument8 SeitenMrichchakatika - A Chronicle of Its MilieuSehajdeep kaurNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overcome Shame by The Grace of God and The Blood of Jesus ChristDokument1 SeiteOvercome Shame by The Grace of God and The Blood of Jesus ChristELBERT ESTABILLONoch keine Bewertungen

- Divine Service Message February 6, 2021Dokument14 SeitenDivine Service Message February 6, 2021Carlito F. Faina, Jr.100% (1)

- Readings. State Nationality and StatelessnessDokument7 SeitenReadings. State Nationality and StatelessnessMAYORMITA, JIMSYL VIA L.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Life Christ Stereo 1969Dokument134 SeitenLife Christ Stereo 1969Jason Groh100% (6)

- The Mongols - A Very Short IntroDokument152 SeitenThe Mongols - A Very Short IntroRichard LeongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Killed JesusDokument3 SeitenWho Killed JesusLyn VertudezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Burton Watson - Chuang Tzu - Basic Writings-Columbia University Press (1996) - 17Dokument10 SeitenBurton Watson - Chuang Tzu - Basic Writings-Columbia University Press (1996) - 17Devi ShantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Silent Past - Ivar LissnerDokument448 SeitenThe Silent Past - Ivar LissnerIsrael Verda Koro100% (3)

- TashlichDokument8 SeitenTashlichAbraham KatzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jonathan Klemens - Ancient Celtic Myth, Magic, and MedicineDokument7 SeitenJonathan Klemens - Ancient Celtic Myth, Magic, and MedicineVladimir ĐokićNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Fits AmanDokument23 SeitenWhat Fits AmanTemitope Isaac DurotoyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SP5Dokument3 SeitenSP5Damaris Pandora SongcalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal EvangelismDokument27 SeitenPersonal EvangelismErica Mae SionicioNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Anthology of Ismaili Literature - Introduction (Part Two)Dokument3 SeitenAn Anthology of Ismaili Literature - Introduction (Part Two)Shahid.Khan1982Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Being A WomanDokument16 SeitenThe Art of Being A Womandebij100% (3)

- Dvaita Advaita Etc-Libre PDFDokument11 SeitenDvaita Advaita Etc-Libre PDFAkshay PrabhuNoch keine Bewertungen

- 21 Jun 2021Dokument1 Seite21 Jun 2021vanitha_my82Noch keine Bewertungen

- THAT NIGHT IN ROOM 401 FileDokument110 SeitenTHAT NIGHT IN ROOM 401 FileMinerva Laura89% (9)

- Development of Natural Law Theory - IpleadersDokument12 SeitenDevelopment of Natural Law Theory - IpleadersAnkit ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modernism & PostmodernismDokument5 SeitenModernism & Postmodernismlidyalestari_lsprNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slovenia SA Newsletter: Summer - Poletje 2009 - 2010 No.52Dokument16 SeitenSlovenia SA Newsletter: Summer - Poletje 2009 - 2010 No.52SloveniaSANoch keine Bewertungen