Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Wagner+Moll+Newell2011 2

Hochgeladen von

Aniket MehtaCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Wagner+Moll+Newell2011 2

Hochgeladen von

Aniket MehtaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Management Accounting Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/mar

Accounting logics, reconguration of ERP systems and the emergence of new accounting practices: A sociomaterial perspective

Erica L. Wagner a , Jodie Moll b, , Sue Newell c,d

a b c d

School of Business Administration, Portland State University, 631 SW Harrison Street, Portland, OR 97201, United States Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, Oxford Rd, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Department of Management, Bentley University, 175 Forest Street, Waltham, MA 02452, United States Warwick Business School, UK

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

This paper extends our knowledge on how software-based accounting tools might work effectively within an organization. The empirical data that we focus on are events that unfolded following the introduction of a new ERP system at an Ivy League University. We describe a negotiation process that occurred after roll-out that resulted in a reconguration of the ERP to integrate some of the legacy functionalities that were familiar to organizational participants and which were considered by them to provide a more effective way to manage their nances. Our contribution to the literature is not only to show the importance of such post-roll-out modications for creating a working information system, but also to extend previous accounts of non-linear accounting change processes by emphasizing how these modications are dependent on the particular entanglement of users and technology (the sociomaterial assemblage) rather than either features of the technology or the agency of the humans involved. Moreover, our analysis of the case data suggests that management accounting in particular may not be easily captured in ERP packages, even where the technology architectures are supposedly designed for a particular industry. The case data also points to issues of affordability and the power of communities of practice as mediating the extent to which these familiar accounting logics may become integrated within the ERP system. 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Enterprise Resource Planning systems Accounting logics Sociomateriality Reconguration Legacy assets

1. Introduction In the face of competitive global markets and constant innovations in technology and business models, changes to accounting information systems are often implemented. In particular, many organizations adopt accounting software packages (as variants of Enterprise Resource Planning [ERP] systems) to improve the transaction processing capabilities (Booth et al., 2000; Dechow and Mouritsen, 2005), co-ordinate record keeping (Chapman and Kihn, 2009),

Corresponding author. E-mail addresses: elwagner@pdx.edu (E.L. Wagner), Jodie.moll@mbs.ac.uk (J. Moll), snewell@bentley.edu (S. Newell). 1044-5005/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.mar.2011.03.001

reduce costly duplications of data (Dillard and Yuthas, 2006; Scapens and Jazayeri, 2003), enable centrally stored information, making it easier to create different types of nancial reports (Chapman and Chua, 2003) and improve duciary control (Wagner and Newell, 2006). Much of the literature in accounting has assumed such technology to be an exogenous force of change for accounting work routines (Granlund and Malmi, 2002; Rom and Rohde, 2006, 2007; Scapens and Jazayeri, 2003). From this view, the functionality of the system is set when the adopting organization ips the switches of thousands of embedded templates. These templates provide the organization with a catalogue of standard work practices the so-called best practice logic purportedly embedded within the product (OLeary, 2000; Wagner and Newell,

182

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

2004; Wagner et al., 2006; Sia and Soh, 2007). Once the conguration options are selected this will supposedly determine how accounting will be practiced. However, technology alone cannot force practice change, especially when the best practice design logic is misaligned with the legacy practice logics. Where such incompatibility exists resistance is often encountered (Berente et al., 2007). These kinds of problems are prominent in relation to the implementation of ERP systems because their integrated nature means that the work processes of different groups and departments become more tightly coupled than was often the case in the legacy system environment when each department/function had its own stand-alone IT system. Research shows that often organizations only realize the incompatibility in practice logics once the congured system is rolled-out and users nd that they can no longer carry out their legacy work practices and so begin to resist (Wagner et al., 2010; Leonardi and Barley, 2008). This leads many organizations into a prolonged period of negotiation and may result in substantial customizations to the ERP (Wagner and Newell, 2006) or other adaptations, despite this practice being discouraged by vendors and traditional systems development theories (Boudreau and Robey, 2005; Berente et al., 2007, 2008; van Fenema et al., 2007). For instance, prior eld studies (Malmi, 2001; Granlund and Malmi, 2002) have demonstrated that as ERP implementation projects unfold, and there is realization that the system is unable to cope with the accounting demands, organizations are prone to developing separate spreadsheet solutions or specialised software such as Cognos that can provide more exible analysis of the accounts. These studies have shown that specialized software used to capture the specications required of advanced management accounting techniques, such as the balanced scorecard and activity based costing, may over time be added to ERP-type technologies. That ERP systems might require such modication has led several scholars to be critical of using them for management accounting purposes arguing they are too complex for this type of architecture (see Rom and Rohde, 2007, p. 50). They suggest that ERP systems be viewed as transactional management systems that are not designed for strategic level management. Furthermore, stand-alone software systems, which can provide a more user-friendly and exible basis for analysis and reporting and more ad hoc management accounting practices, may provide a less risky and more cost effective alternative (Rom and Rohde, 2006; Hyvnen, 2003). But, evidence from scholars such as Chapman and Kihn (2009) suggest that managers can be satised with systems that possess high levels of integration even where they do not lead directly to improvements in performance. In keeping with the later cadre of research, we extend knowledge related to how ERP technologies are made to work as systems (Chapman, 2005) through a nonlinear process of change (Quattrone and Hopper, 2001). We provide an analysis of a case that shows how ERP systems can be recongured to incorporate legacy practices and satisfy the exibility (i.e. precision and frequency) demanded of managerial accounting. In doing this, we demonstrate not only the importance of post-roll-out modications for creating a working information system, but also emphasize how these modications are dependent on the particular

entanglement of users and technology (the sociomaterial assemblage). In adopting this perspective, we seek to go beyond realist accounts that focus on the features of the technology determining structures or social constructionist accounts that emphasize the agency of the humans involved (Leonardi and Barley, 2010). We identify how contexts of use will differ in terms of the types and scope of modication that are made in the post-roll-out phase and thereby extend the literature on accounting change as non-linear and relational in nature (in particular, Andon et al., 2007; Dechow and Mouritsen, 2005; Quattrone and Hopper, 2006). In this paper then, we do not reject the potential usefulness of an ERP system for management accounting but rather argue that the value of any information system, whether it be integrated or standalone, can only be understood by focusing on how accounting, IT and its users are entangled to produce managerial accounting practice. With this in mind we focus on two research questions: (1) what and how are accounting logics encoded within ERP systems? and (2) how, in the process of users interacting with the ERP and retrieving information, do new accounting practices emerge and does the system become recongured to support them? These questions allow us to consider how the logics underpinning practice are sensitive to local circumstances and cannot be fully specied in any strongly determinant way (Suchman, 2007, p. 53) even though ERP-architectures inscribe, in their vanilla-state, particular ideals about practice, i.e., particular practice logics. We explore the questions by examining the postimplementation negotiations of a troubled ERP project in an Ivy League university. The project was at risk of being abandoned because of the practice logics that were initially congured into its grant accounting module. The ERP was congured to support the nancial accounting needs of the central administrative function composed of professional accountants. However, the integrated nature of ERP meant that these system architectures were not sufciently exible for enabling faculty to manage their research project budgets in their preferred ways. We thus identify how the ERP-system was customized to enable the university (hereafter Ivy) to accommodate the practices of both the nancial accounting centre and the faculty managing their project budgets. The remainder of the paper is structured in 4 sections. In Section 2 we discuss the key concepts which inform the sociomateriality lens, enabling us to see in the data the process of negotiation that occurred within the case of a university in the post-implementation phase of their ERP project, ultimately resulting in that system drifting to eventually support some legacy-type practices even though initially these were explicitly excluded. Section 3 outlines our research methods. Section 4 presents the case description and analyzes two grant accounting practices and the negotiation process that ensued at go-live. In Section 5 we discuss the meaning and implications of our analysis for implementing enterprise-wide accounting functionality within organizations. The paper concludes with suggestions for future research.

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

183

2. A sociomateriality perspective of accounting practice 2.1. Nature of sociomaterial practice We adopt a practice theory perspective to yield insight into how accounting is made workable when it is entangled with an ERP system. This approach is becoming increasingly popular for its ability to offer new and interesting insights to accounting change (cf. Dechow and Mouritsen, 2005; Jrgensen and Messner, 2010; Macintosh and Quattrone, 2010; Pentland et al., 2010). Practice theories focus on peoples everyday activities, analyzing how they are produced and reproduced in a particular historical and social context (Levina and Vaast, 2005). This approach considers accounting as a thing that people do. This means it cannot be reduced to a set of routines that are enacted as designed across time and locations (cf. Scapens, 1994; Burns and Scapens, 2000). The focus on practice reects the idea that it is at the level of everyday activity that learning occurs as people and their technologies take on particular shapes and meaning through situated use. Practices are considered to be in a constant state of change, albeit some changes are very small. This means that there are always inconsistencies, even when people are supposedly carrying out the same practice: pursuing the same thing necessarily produces something different (Nicolini, 2007, p. 894). There are many variants of practice theory1 ; however, here we analyze technologyhuman interaction from the sociomateriality practice perspective outlined by Orlikowski (2010) and Suchman (2007). This perspective does not assign agency either to persons or things but considers the social and technological to be ontologically inseparable, yet constitutively entangled (Orlikowski, 2010; Orlikowski and Scott, 2008). It provides a way to understand how meanings and materialities are inextricably related and inuence the form of (accounting) practice. Importantly, this relational ontology suggests that once one begins to look at an integrated information system like an ERP, despite it retaining an organizational identity, multiple person/technology assemblages may be observed that help to explain how accounting can be interpreted and enacted differently by users even in the same organization (Quattrone and Hopper, 2001, 2006). It is for this reason that Quattrone and Hopper (2006) refer to such systems as being heteromogeneous. This occurs, they argue, because the logics underpinning accounting practice are sensitive to local circumstances and cannot be fully specied even though ERP-architectures inscribe, in their vanilla-state, particular practice logics. In sociomateriality terms this focus on how relations between humans and technologies become enacted in practice is referred to as performativity, which helps us to understand how and why such systems are prone to reconguration.

2.2. Relating notions of reconguration to accounting and ERP technology In a packaged software product, the way the ERP technology is initially constituted is inuenced by the particular conguration options selected plus any customizations introduced. The accounting logics encoded in the software may be designed with certain problems in mind (i.e. costing and performance measurement) (Dechow and Mouritsen, 2005) but they also involve inevitably vague categories (i.e. inventory) so that they can capture a broad range of organizational activity (Chapman and Chua, 2003). Trade-offs between organizational and technical concerns will also add to incomplete representations of the organizations circumstances and this enables those downloading and interpreting accounting information produced by the ERP system to translate it and use it in different ways depending on their intentions and adaptive abilities (Bloomeld and Vurdubaki, 1997; Busco et al., 2007; Dechow et al., 2007; Dechow and Mouritsen, 2005). More bluntly put, an ERP system cannot be understood to present information that objectively reects some reality, or as neutral technical solutions and tools (Ciborra, 2002, p. 68; in accounting see Hopwood, 1983, 1987). The designer2 /users viewpoints can be and are inuenced in the process of downloading, interpreting and using the data. It is this reexivity between the ERP-system and the user that suggests that the design of an ERP-system with integrated accounting functions is not something that stops when a system goes live. Rather design is an on-going sociomaterial practice performed over time (Suchman, 2007, p. 278). Previous studies of accounting and IT, borrowing from Ciborra (2002), use the term drift to describe the processes by which these systems change (Quattrone and Hopper, 2001; Andon et al., 2007; see also Macintosh and Quattrone, 2010). It has been argued that drift resembles incomplete attempts at organizing (Quattrone and Hopper, 2001, p. 428) and provides an explanation of the many ways in which IT systems can be altered through encounters with those using them such as sabotage, learning-bydoing, or plain serendipity (see Ciborra, 2002, p. 89 for a more in-depth discussion). This concept enables one to understand how an organization might end up using legacy practices when new IT is introduced even where particular legacy practices were purposefully designed out of the IT architecture. For analytical purposes, this perspective suggests it is important to explore the initial design/conguration, who was involved/excluded, and then to follow through to examine how the sociomaterial assemblage is re-congured through a process of negotiation (Ciborra, 2002; Orlikowski and Scott, 2008). The mangling of the social and technical thus produces a dialectic that Pickering (1993) depicts as a series of resistances and accommodations; here we explore this dialectic across time and across practice communities.

1 Ahrens (2009) suggests some of the more commonly used approaches in accounting include governmentality, actor network theory and accountability.

2 In this paper we use the term designer since the project involved designing a new ERP for the university market.

184

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

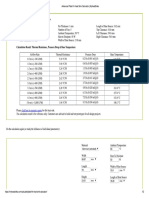

2.3. Communities of practice, accounting logics and relationality As Law and Singleton (2005) indicate the nature of a thing depends on its nests of relationships (both those absent as well as those present). For example, with the implementation of an ERP system people may not be able to get the accounting information that they need or expected to be able to get. Thus, there can be an information asymmetry between people and machines limiting the scope of interaction, and the capacity for accounting practice and subsequent action (Suchman, 2007). This view assumes that ERP is an essential part of practice in organizations and by inscribing specic accounting logics sets limits on forms of calculation. In Orlikowskis (2005) terms these material arrangements scaffold social activity in particular ways within practice communities. In the process of using the system, individuals and/or communities may end up questioning these logics. In the past, practice communities have been relatively autonomous so that people/technology assemblages have evolved in distinct ways, even if they are using the same technology. With an integrated ERP this independent evolution becomes more difcult and the multiple sociomaterial assemblages become more mutually constitutive. Thus, if one practice community decides that the accounting logics inscribed within the ERP should change to better reect the economic reality of the local entity or its products or processes, they would need to impose this on others who may believe the existing practice to be adequate. Unless those communities with differing preferences regarding what are the appropriate accounting logics can be decoupled, so that each could use their preferred form of calculation, a period of negotiation would begin. Such decoupling is more difcult in an ERP environment, so the emergent sociomaterial assemblage within any particular practice community is restrained by other sociomaterial assemblages one practice community cannot evolve the system without it inuencing others who may then resist attempts to modify the technology. Conict is generated because for some communities the co-evolving ERP may enhance the sociomaterial relationship (as when an accountant in the central ofce gets data from all distributed departments via the ERP in one format that makes his/her job of reconciliation easier) while in other cases it may distract from the relationship (as when the faculty member can no longer get the information that s/he feels is needed from the ERP to manage a research budget). The sociomaterial practice perspective that we describe in this section is designed to provide a more inclusive view of how accounting practices emerge from the complex and shifting assemblages between the accounting calculations, the IT architecture and the people in the organization (Orlikowski, 2010). We next describe the methodology that allows us to see these shifting assemblages. 3. Research methods The empirical sections of this paper are informed by a longitudinal case study (138 interviews with 53 employees) (see Table 1) between June 1999 and April 2010. The

majority of the eld work was conducted over the course of 18 months between June 1999 and August 2000 but a series of follow-up interviews were conducted with a subset of the Ivy population in 2002, 2005, and 2010 in order to keep current with the state of the ERP and administrative work practices at the University. The 18-month intensive eldwork phase corresponded with the implementation and post-implementation of the ERP project. The rst author made four visits to the eld site where she was embedded within the ERP project environment for eight weeks at a time (summer 99, winter 99, spring 00, and summer 00). During these intensive data collection periods the researcher attended meetings, reviewed formal documentation, and conducted interviews. Years prior to conducting this study, the rst author was employed by Ivy as an accountant. This proved to be helpful for understanding Ivy University norms and communicating using local colloquialisms. The other two authors became involved only after the eld study was complete. Recognizing the performative nature of some language, a narrative interview convention was adopted in order to avoid asking leading questions.3 The narrative interview convention provides a time frame to structure the interview [Tell me what happened since we last met.] and then encourages uninterrupted storytelling related to issues of central importance to the interviewee (Bauer, 1996). Rough transcripts of each interview were produced directly following the days meetings and analyzed in terms of actors and issues discussed. Recurrent themes were followed up in the next round of interviews in order to gather multiple perspectives of the same situation and develop an understanding of the negotiations that were central in peoples minds at the time. This approach was also helpful for reaching those actors who might have remained silent voices (Star, 1991), because the eld researcher was guided not only by interviewee referrals, but also by contacting allies and controversial agents whose names arose in the interviews. When a reference was made to a group, cause, or action attributed to nonhumans such as the ERP itself, the researcher interviewed a delegate and reviewed technical documentation (Pouloudi and Whitley, 2000). After each phase of eldwork, the rst author re-transcribed the rough transcripts in order to communicate the spoken features of discourse such as tone, mood and pace of the narration (Riessman, 1993), and to ll in all missing narrative. The analysis in this paper represents a re-examination of the original data focused on specically contributing to the accounting literature related to the entanglement of accounting logics and ERP software. The data was rst analyzed with the intention of understanding the logics of Ivys accounting practices. Next, we undertook a systematic and careful reading of the transcripts using the three theoretical constructs introduced in section two: sociomaterial

3 Follow-up interviews in 2002, 2005 and 2010 were semi-structured in that several specic questions were asked by the eld researcher and interviewees were also free to tell stories about the issues that were most prominent to them about recent developments.

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197 Table 1 Interviews conducted at Ivy League University. Participants 6 Community of practice Central administrative leader Project managers Project team members Total central administration and project team End user Faculty Total faculty and faculty support staff Total Summer 99 3 Winter 99 1 Spring 00 5 Summer 00 3 Summer 02 2 Summer 05 2

185

Spring 10 2

9 17 32

8 17 28

5 12 18

6 11 22

6 11 20

1 1 4

1 0 3

0 0 2

12 9 21

6 0 6

5 4 9

12 6 18

5 3 8

0 0 0

0 0 0

0 0 0

53

34

27

40

28

practice, reconguration, and relationality. This enabled us to identify several episodes of negotiation from which the entanglement of accounting logics and IT architectures could be observed to produce a change in the accounting practices that were used within Ivy. We focus on these in the empirical sections of the paper to understand the variances between the accounting logics inscribed in the ERP system and those that had shaped the accounting practices that had been improvised by staff. We were thereby able to empirically examine the modication of both the software and work practices which has not received much attention in the accounting literature. 4. The case: ndings and analysis In this section, we rst describe the organizational context. Next, we consider the accounting logics underpinning the legacy practice of commitment accounting and its replacement practice time-phased budgeting. Following this we examine the negotiation process that occurred leading to the emergence of new accounting practices and a recongured ERP system. 4.1. Organizational context Ivy University is one of the eight Ivy League institutions located in the Northeast region of the United States that are grouped together for their academic excellence and selective private education. The governance structure of Ivy is relatively decentralized with administration taking place in the disparate academic and support departments and then consolidated and reconciled centrally in order to report nancial status and meet regulatory concerns. The lifeblood of a research university is the receipt and effective use of research grant monies. Ivy has over 4000 different grants for which they have duciary responsibility. Grants and contracts revenue account for close to 30% of the Universitys total operating budget. Within Ivy, grant activity is rolled-up and reported alongside all other University funds for two main reasons. First, improper management of grant dollars can potentially increase the Universitys risk position. Grant related activities are closely scrutinized by legal counsel and Ivys

Internal Audit department who work in collaboration with external auditors. Consequently, audit compliance is a concern to Central leadership and bears signicance on any decisions regarding modernization of Ivys administrative systems. Second, the mismanagement of grant funds can become a liability for the institution. As such, Central leadership is motivated to decrease inconsistencies in practice across faculty grants. From the academic perspective, when a faculty member is awarded funds from an external grant agency there are certain reporting requirements tied to the use of the monies. Funding bodies typically make awards based on the initial monetary requests in the grant application where detailed categories of expenses submitted in the application sum up to the total grant award. Principal Investigators (PIs) on grants usually have multiple proposals and awards ongoing at any given time meaning that their scientic activities are project driven but the University general ledger and chart of accounts do not support project-oriented reporting. Faculty are concerned with scientic endeavours that are enabled through the grant funding. This often means that a PI will spend grant funds based on how much grant money remains without ever writing a formal plan for how the funds should be spent over time. The various practices faculty employed in such reporting activities lead to inconsistencies in Ivys overall accounting practices. In this climate, Ivy embarked on an ERP project to replace all administrative systems and create an integrated operating platform for the 21st century. The choice of an enterprise computing model was expected to increase duciary control and decrease audit risk while funnelling more administrative responsibilities from the central administration to academic and support departments. The introduction of an ERP is an example of a situation where Ivy leadership anticipated change around a best practice ideal. Theoretically, however, we understand that even though an ERP-architecture would inscribe a particular grant accounting logic, actual accounting practice will be sensitive to local circumstances (Suchman, 2007). Ivy contracted with a single software vendor (Vision) to adapt their government-ERP system by developing two new modules uniquely needed for the higher education

186

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

context (including managing projects associated with grant awards) that would be rst implemented in Ivy. Vision was expected to provide a robust nancial system that would integrate accounting and budget functionality with all other administrative functions. This strong nancial functionality drove vendor selection: I heavily leaned in [the] direction of wanting to go with the strongest nancial system. I thought that the largest pay-off from the project, when you really looked at it, ultimately would be in better nancial data and the ability to do more interesting things on the clinical and grants management side. . .[these] things seemed to me would drive the process to create a robust business environment. [VP for Finance and Administration, summer 1999] Ivy conducted system-modernization and businessprocess redesign efforts within the key functional areas of nancial management, human resources and payroll, and grants and contracts administration. The nancial management components included general accounting, nancial planning and reporting, purchasing and accounts payable. Because of the importance attached to the management of project funds, the capability of the system to monitor the present state of accounts in relation to past expectations and future plans were key criteria in designing the system. It was also rationalized that an integrated approach would simplify future upgrades and promised to minimize the need for expensive migration efforts later on. Institution-wide all-fund budgeting would also be possible without time-consuming and error-prone manual reconciliations. Such motivations are not uncommon especially when seeking to retrieve accounting-based information in an integrated manner to create different types of reports (Chapman and Chua, 2003). Ivys academic communities, that had historically been relatively autonomous and evolved practices that were distinct, would now become more interdependent. This approach was expected to professionalize the workforce by shifting the types of questions and analyses that faculty and their support staff were asking with regards to their nancial position: By making a decision to go with [Vision] nancials senior management either consciously or semiconsciously I think it was for former was making it impossible for [Ivy] to continue doing business in fragmented silos. Like it or not, youve got to work with a new way of accounting. Its integrated its slower, its a pain in the ass. . .and the blue-haired ladies who used to do it the old way for years decide its absolutely terrible they dont want to do it cause its not Ivys way. But implementation is about setting up an environment. You make a set of decisions a set of changes at the top that force change regardless of whether its consensus or not cause you say you change their ability to do it any other way. You just cant do grant accounting like you used to do grant accounting! Nothing you do is going to change that no amount of moaning is going to change it. . .They can re [the VP], they can re [the controller], they can re me, but nothings going to change the fundamental you cant go back and you cant spend enough

money to make it look like it used to. . .You dont like it? Youre out of the consensus picture. If you are more inclined to accept the changes and deal with them, then you are in the narrow universe of people we will work to have consensus with. [Technical team leader, summer 2000] Academic constituencies4 and Central administrators all recognized the importance of moving away from discrete silos of activity to an integrated and more transparent accounting practice to manage institutional risk, comply with regulatory bodies, avoid litigious hazards, and act as competent duciaries. The Director of Financial Planning, a spokesperson for Ivys institutional perspective, stressed the importance of accountability and control for Ivys future: . . .Certainly the motivation for having this more high powered enterprise software is that the place has become more complex and we need better data. We need to make better decisions based on data. . .its a recognition of the need to do that because were running a huge nancial behemoth. Were the highest graded nancial institution in the state. All these. . .for-prot companies arent rated as highly as we are. Were Triple A: Triple A in both Moodys and Standard & Poors. I mean you know its extraordinary. We have a billion dollars of debt. Thats a billion dollars of bond holders out there that are, you know, trusting us with their money. So its extraordinary,. . . [summer, 2000] This nancial management vision spearheaded the ERP project. Ivy needed to institute new practices that would increase their control of nancial transactions and address accountability through ofcial statements of record. Shifting accounting practice was also seen to be important for managing future operating activities through iterative cycles of planning, budgeting, review, and reporting. This led designers of the original ERP to purposefully design-out, the budgeting practice logic of commitment accounting and design-in what they considered should be the new practice logic, that would be mandated as the institutional standard, of time-phasing. From the practice perspective, we expect negotiations to ensue because previously autonomous practice communities are coupled and no longer able to use their preferred form of calculation for grants management. Indeed, this turned out to be a contentious issue for the University that resulted in academics refusing to work with the nancial management module. In this way the Ivy study supports existing accounting literature that found ERP systems to encroach on vital but idiosyncratic local knowledge leading to the creation of work-arounds (Chapman and Chua, 2003; Quattrone and Hopper, 2006; Hyvnen et al., 2006, 2008; Granlund, 2007). Over a short period of time the sociomaterial assemblage was upset and the accounting practices began to

4 The academic constituency included faculty, their support staff (FSS) and academic managers. FSS completed administrative work on behalf of faculty and were their rst point of contact. FSS were overseen by academic managers who were responsible for programmatic and administrative functions within a department or area.

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

187

shift from those that had been pre-dened and congured. In Ciborras (2002) terms it began to drift. Long standing legacy assets were bolted-onto the ERP system in order to create a working information system that was used by both academic and administrative communities. The notion that even when doing the same thing differences in practice are inevitable (Nicolini, 2007) foreshadows the sociomaterial negotiations involved. We identify the post-implementation phase as one of re-guring the grant accounting practices and as one that was reective of the way in which the users and technology were constitutively entangled. The relationality between different elds-ofpractice at Ivy helps us to understand how a working information system was created that involved sociomaterial accommodations that included the support of some legacy-type practices (commitment accounting) alongside the system-supported best practices (time-phased budgeting). This organizational context sets the stage for investigating peoples everyday activities and analyzing how these activities are produced and reproduced in a particular historical and social context (Levina and Vaast, 2005). Each construct, along with the negotiation process explaining how new accounting practices emerged, is described in Table 2. 4.2. Sociomaterial practice: the logics of commitment accounting and time phased budgeting Long before the conceptualization of ERP modernization at Ivy, persons and things were gured together in a particular way in order to manage scientic activities funded through grant monies. This sociomaterial conguration was formally known as commitment accounting where people and their technologies took on particular shapes and meaning through situated use. Faculty and their Support Staff (FSS) were largely responsible for adjusting all discrepancies between what the PI actually spent in a particular budgetary category and what had been budgeted. This reconciliation process involved handwritten notes/emails to administrators from faculty about their spending activities, printed reports from the Mainframe nancial system, PI Reports from the Distributed Accounting System (DAS), and MS Excel. The DAS was written in Focus programming language by faculty and staff in the late 1970s and had a very basic interface allowing users to enter and download data from the mainframe nancial chart of accounts, match them with detailed categories that the faculty decided and then reconcile that balance with what faculty was committed to spend. PIs told administrators how much money to set aside for project activities. They referred to these obligations as commitments. Administrators classied these commitments into one of two conceptual categories: pending actuals and future plans. The former represent expenses that had been incurred but for reasons of timing, had not yet hit Ivys general ledger and were excluded from that cycles mainframe nancial reports; whereas committing for future plans took into account activities that PIs expected to occur at a later time, but before the completion of the grant. To budget for these categories administrators

had to probe the PI about their scientic activities to get them to identify, classify, and earmark as many dollars as possible from the current instalment of the grant. While these conversations were held with all PIs the granularity and frequency of these discussions was a locally negotiated outcome. Individual temperaments, available time, departmental norms, professional working relationships, and the stage and nature of research, all inuenced the extent to which future expenses were identied, entered through the DAS interface, and classied as commitments that were expected to occur during a specic grant period. The ad hoc nature of grant accounting makes it evident why a practice theory lens is so important because it allows us to see how small variations in process are inherent to conducting work even when it is supposedly the same practice, in this case monitoring grant dollars. The project management process links the PI back to the funding body reminding her of what she said she would do to achieve her academic goals and while each PI has reporting obligations, how she gets to this stage will vary (Nicolini, 2007). PIs viewed the pending commitments as money that had been spent therefore it was expected that the balance of the grant reected this. This amount was recorded in a PI report. This PI report was different from the nancial statement of record aka the Greens which were colour-coded nancial statements reporting only the actual income and expenses that hit the general ledger in that nancial cycle. From time to time, administrators reconciled the Green reports against the DAS system and the PI Report to make sure the commitment accounting system was pulling the correct numbers from the mainframe nancial system. Together these material arrangements scaffold commitment accounting grant management practices and in turn, the viewpoints of users were inuenced in the process of downloading, interpreting, and using this accounting data in a reexive manner. The PIs had learned to see in a particular way that was supported by the sociomaterial arrangements of commitment accounting. Each PI was involved in the practice of creating a close enough match of actual research activities to the artefact of the nancial system and its statement of record. Goodwin calls this process of learning the meta-data of work practice part of developing a professional vision (within Suchman, 2009) in this instance the vision of being a scientic principal investigator. The nature of grant accounting, thus, depended on the nest of relations between the people and things involved in the accounting practice. For central administrators, this form of reporting was seen to be indicative of the poor nancial planning practices of faculty. This was made no more obvious to them than when they considered the spending patterns of the PIs who were in the habit of going on sprees as the grant completion dates began to close in. The PIs wanted to try and reach a zero balance to ensure that funding would not be returned to the funding body. Around the time that Ivy had decided to replace its legacy systems this practice had become so problematic that central accounting had begun to ask questions about the large accounting transfers that were recorded late in the life of externally funded grants. The central accountants were concerned that auditors would see inconsistencies (e.g. spending $4000 a month

188

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

Table 2 Key constructs for explaining how new accounting practices emerge. Theoretical construct Sociomaterial Practice technical agencies are tied together with those involved in the practice; an ERP sets up a particular sociomaterial conguration. Reconguration focuses on how persons and things might be gured together differently when resistance is encountered to a new sociomaterial arrangement following ERP implementation. Relationality multiple practice communities exist across the eld of accounting within an organization; different communities will have more or less power to inuence the sociomaterial practices surrounding an ERP conguration/reconguration and this can change over time. Illustration Many local grant management practices existed that were accommodated by the commitment accounting sociomaterial conguration but were undermined by the new time-phased budgeting conguration. Eventually the project team responded to the demands of faculty and worked with them to re-congure the ERP to accommodate faculty ways of working and set up various support structures. During design, the ERP-project team congured the ERP to meet their needs. Following implementation this met with faculty resistance; faculty were powerful voices within this environment and so were able to force others to listen to their needs and interests and so effect the reconguration.

for 10 months and the last 60 days charged $85,000) in the spending process making the transfers suspect in terms of reecting actual scientic practice. Next, we consider the proposed integration of management accounting activities through time-phased budgeting. As Suchman notes (2009) professions constitute those things that are their objects. For example, part of becoming a scientic scholar and PI on a grant is becoming congured with the relevant materials and tools. These tools extend beyond the tools of laboratory experiments and data analysis software to include the materials used to manage the funds supporting the research. The PIs professional training enables them to work with imperfectly designed tools and make decisions when the output is not exact this is a form of sociomaterial practice. Similarly this is true of accountants and budget leaders who must reconcile incomplete and imperfect data sources in order to accurately report institutional level scientic activities. From a sociomaterial perspective this imperfect conguration is part-and-parcel of practice (Nicolini, 2007). It is the multiple partial information sources (both human and technical) that, when brought together, create a working system; indeed, it is the ad hoc nature of the conguration that is part of what makes the information system work (Suchman, 2009). Next, we consider the proposed integration of management accounting activities through time-phased budgeting. The time-phased budgeting practice was a standard information architecture that was an integral part of the ERP system that was implemented. It had been in use within the Central Budget Ofce for over a decade in order to improve Ivys institutional planning and overall corporate governance activities. The Director of that ofce spearheaded the time-phased budgeting practice as the logic for ERP-based grant accounting. The shift in grant accounting practice tells us a lot about the nature of accounting practice being produced at the end of the 20th century during a time of societal uncertainty related to Y2K and large corporate scandals related to nancial reporting. The technical agencies of ERP and the time-phasing algorithm were to be tied together with the academic constituencies. Time-phased budgeting is based on recording each nancial transaction in a chart of accounts category (expense, revenue, capital, etc.) thereby allowing University managers to budget for future years by estimating the

sum of each category at the institutional level. The capacity for action was quite different from the sociomaterial assemblage of commitment accounting. Time-phased budgeting begins when faculty and staff meet at the beginning of the scal year for an extended nancial budgeting session. This provides the opportunity for all projects to be mapped out in terms of spending over time. There are no printed nancial reports, rather the two individuals sit in front of a computer screen and view all faculty projects from what is called the project-centric view of grants. The decision to disallow the printing of monthly statements was done both to save Ivy money in printing and distribution and mostly to encourage a more uid interpretation of numbers where users reect on nancial numbers as xed only for a short period in time before they change (Director of Financial Planning). Instead of providing tools that would perpetuate the detailed tracking of nancial commitments, faculty and staff were asked to investigate materially signicant variances to the budget plan always considering the current expenditure in relation to the grants timeline. Persistent overspending would be investigated because it could impact a grants longevity if the pattern continued. Through time-phased budgeting both the faculty/staff (subject) and their grants (object) are transformed in their relations with each other (Suchman, 2009). Faculty themselves were not capable or interested in time-phasing their grant monies, but the ERP design-inscribed time-phased budgeting as a particular accounting logic set limits around what processes of grant management would be considered appropriate for the University. Under the guidance of their administrator, PIs were supposed to mimic the pace and rhythms of their research projects by coming up with a budget plan for their multiple grants. This approach was designed to allow them to achieve their academic goals without having to think in terms of the detailed nancial chart of accounts. In the beginning, each project is divided into broad categories of spending throughout its duration. Then grant funds are applied to cover the planned activities and categorized by type of transaction as well as the time when the transaction will occur. Faculty and staff then monitor these plans in comparison to the monthly nancial transactions. This regular comparison was designed to encourage reexivity as part of the nancial management process enabling timely and corrective interventions to be made to the grant bottom line. The time-phased budgeting module generates

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

189

reports at the end of each month comparing how closely the PI matched the budget for that period in time thereby scaffolding the practice of monitoring grants. Over the longer term the intention was for the timephased budgeting to be further decentralized removing administrative intervention and asking faculty to monitor, review, and report on their grants themselves. This was made plain in the following interview: I mean lets give the job directly to the faculty. It doesnt take a Nobel Prize winner to say Ive got $50, I spent $65, Im in trouble for $15. Thats really all were talking about. And it doesnt take a Noble Prize winner to do a business plan thats timed out by months or quarters. So you know, when we talk about somebody who is a secretary whos put into a position with the ERP that is now totally too complicated for them, thats really different. I mean if you had somebody with an IQ of 90 and its a job for a person with an IQ of 110, theres a problem. But with the faculty the fact of the matter is theyre all smart! I mean they may be nutty as hell but theyre smart and theres nothing here that they cant gure out. . .I really believe you put pressure on people to take responsibility for things that they should be responsible for and then you hold them accountable for it. Its like the old thing that somebody once said, if you treat people like children, they behave like children. If you treat them like adults, they behave like adults. [Director of nancial planning, summer 2000] 4.3. Reconguration To reinvent the way faculty do accounting, the project team had thus purposely designed the ERP nancial management module without incorporating the possibility for commitment accounting calculations. Faculty were invited to participate in project information sessions but few did, believing that because the system was being designed for them it would, by denition, accommodate their needs. The lack of faculty involvement meant that during the conguration/design stage the choice to exclude commitment accounting was not contentious. However, once the ERP was rolled-out, the reconguration of the sociomaterial assemblage to exclude commitment accounting immediately became a source of tension and resistance. It was at this point that an information asymmetry became apparent between the PIs and the ERP between people and machines where the nest of relationships had been recongured in a manner that limited the scope of interaction with the grant accounting gures and the capacities for human action (Suchman, 2007) in this case forcing faculty to allocate/spend money in a manner preferred by central accounting leadership. The ERP had not been programmed to emulate the same reports as the legacy assets and it was not sufciently interactional that it could access the PIs situation to provide useful information. PIs and other academic staff who were the main users of the system were puzzled when they began to use it, not understanding why their valued commitment accounting logics were absent when the project team had not been constrained by a standardized information architec-

ture and beneted from being the rst industry-specic solution: Why did the integrated technology have to be timephased budgeting when we had [a system] before that worked for the faculty? I mean the legacy [commitment accounting] system could have been fully integrated as an ERP it was technically supported as one, but was only ever managed and used at the departmental level. Why not design [commitment accounting] as the integrated, standardized technology? It worked for faculty for years. . .I hope you understand that its not [the ERP] itself thats the issue. Its the lack of understanding and regard for the people bringing in the money and the people doing the work thats so frustrating. [Academic manager, follow-up email 2002] PIs felt the ERP system had reduced their ability to manage and control their spending. Furthermore, the accounting logic that underpinned commitment accounting was consistent with deeply held values of faculty related to academic freedom: it allowed a exible form of accounting that was capable of adjusting the bottom line to represent commitments in terms of future spending; and also gave them exibility in terms of spending when projects were nearing completion without anyone asking questions about this. At a spur of the moment, faculty were known to demand from their support staff the balance in their account and now this information could not be retrieved. They also could no longer rely upon the customized monthly reports that were provided in the legacy environment to evaluate their nancial position. This put support staff under a great amount of pressure since the ERP was failing to capture and record accurately changes in research activities. Not long after going live with the ERP, tensions between faculty and their support staff became evident: One of my [staff] is quitting. She came out of a meeting sobbing after talking with a new hot-shot faculty member from the United Nations who said I will get the information I need one way or another, you give it to me or I will get consultants in here to get it for me. [This ERP project] is an excuse that you have been using for far too long. She said to me I cant deal I shouldnt have to deal I dont want to take work home like I have been. These high level project guys know that the staff are having a hard time and yet they are not communicating to [Ivy] leadership to get better solutions. Last week a bunch of [FSS] approached [the Director of Financial Planning] and said Tell the faculty that we dont have the tools we need to do our jobs. We know we are not equipped, and you know too why are you not telling the faculty? [Academic manager, spring 2000] As Law and Singleton note (2005), it is as much the absent relationships that determine the nature of practice. The inability of faculty to engage with commitment accounting functionality meant that the capacity for action was designed to be dramatically different in the ERP environment. From a relational ontology we would expect resistance because we understand the logics of timephased budgeting that were inscribed within ERP are still

190

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

sensitive to local circumstances and cannot be fully specied (Suchman, 2009). Academic constituencies began to express disagreement with the proposed grant management practice: We dont know of even one research school that is using this methodology. Weve done some research as an institution and no university we know of is using the [time-phased] method as implemented in the [Ivy] ERP. [Academic manager, spring 2000] Their displeasure became evident to the project team who began to sense a gulf between central administrative perceptions and those of faculty and their staff: Were going to get a faculty revolt cause [Ivy leaders] are going to talk about how great the implementation was from a corporate level and theyre going to talk about how great the new tools are from a corporate level and faculty are going to just be incensed. [Academic leader, spring 2000] The above sentiment foreshadows events to come, which are highlighted in the next two quotes: . . .you look at the faculty and they say well, what do you mean [the ERPs] a success? I dont have my reports. I have no idea how much my grant account or my grant balances are. So there is an enormous disconnect. . . [Project member, spring 2000] In the summer of 2000 an academic leader states: [Ivy] really missed an opportunity to understand the business that ran teaching and research and patient care. . .they focused way too much on giving [Central] the information they needed and not worrying about giving faculty the information they needed to manage the business. So we just focused on the wrong things rst. Rather than acquiesce to the ERPs design, faculty and their staff began to express concern about the ERP-enabled internal control environment in general, and the timephased budgeting approach, specically: We tried to say, I dont really understand why you made the decision to go with time-phasing but lets try to work with it and we tried to, but the reality is we still dont have basic business functionality that our faculty require. [Academic manager, winter 1999] Seeing the difculties their staff were having in trying to work with the ERP and worried that the new academic year would bring with it complications because of this, several PIs and academic staff approached central administration the sponsors of the ERP project with their concerns: The Economics professor [who was] the Provost and used to be the VP for Finance and Administration [for Ivy]. . .called the [current] Provost really angry because he couldnt read his grant report. The [Financial Controller] sat down with him and every concept he was asking for was on that report. But he couldnt see it and his [FSS] couldnt explain it, so shes been making him Excel reports. This guys smart he knows what hes doing and he cant even read the report and I thought that

was pretty telling. So now faculty arent using the ERP and what we have as a result is a very expensive data repository and still a lot of silos of micro-computing. [A project manager, summer 1999] Ivy had congured the practice of grant accounting for the integrated ERP environment in such a way that the relationship between the people and things had caused information and knowledge to be lost (Suchman, 2009). Principal Investigators and their administrators were unable to constitute the relevant objects in the world around them because the practice community of administrators had evolved the technology in a way that enhanced the sociomaterial relationship for central accountants but detracted from the relationship between faculty and their grant accounts. Very powerful constituencies at Ivy were contacting the Provost including one of the professional schools that brought in the majority of all Ivys grant dollars. This is illustrated in the following quote from the Director of Finance at said professional school: We struggled for quite a while [with the ERP] but eventually in listening to our end users say we have to have commitments and the [project team] saying oh, theyre just used to the old system eventually theyll get over it, it became clear not only to them but to us, that no, that isnt the case, theres always going to be a need for being able to do commitments. So what we did, we took that message over to the [project team], and I said look guys, departments really need commitments. We have looked at every creative way of using the ERP in either budgeting, reporting, whatever, and its become clear to us that we need a commitment [accounting] system. And I said were poised at [our professional school] to create our own commitment system but what I would like is to present this as a University issue and I want to know whether or not you would like to join us in this effort? [spring 2000] These acts of resistance and confusion triggered the Provost to organize a series of lunch meetings with faculty members, their staff, and ERP-project team leaders. These discussions convinced the Provost that commitment accounting was a non-negotiable practice for Ivy and was important for managing its institutional risk. She then demanded that changes be made to the ERP software to reinstate commitment accounting functionality. It was at this point that the rhetoric of the project team changed: We became appeasement oriented and so when people began hurting us, we said yes. And so we started building these things that could create commitments and manage commitments. . .even though it was against our original ideas about what was the way forward for [Ivy]. [A project manager, summer 2000] In an attempt to move the project forward and get the faculty to work with the ERP, the team agreed that three courses of action were necessary. First, they would emulate commitment accounting practices in the ERP environment by developing software that could bolt-on to the existing accounting practices. Second, for the sixty days that it would take them to customize the software they would

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

191

allow PIs to use the legacy commitment accounting System. Third, they would make organizational changes to support the transition to an ERP-enabled environment. 4.4. Relationality Given that grants management practices had historically been relatively autonomous at Ivy and faculty evolved technologies in distinct ways to meet their reporting needs, one solution would have been to decouple the grant accounting practices. However, with an integrated ERP platform, this independent evolution is unrealistic. Instead, the period of negotiation described above led to nding a sociomaterial assemblage that effectively comingled practice logics within an integrated infrastructure. To remedy faculty resistance, the project team reorganized post-installation development priorities and created ERP-based commitment functionality. The standardized information architecture of the ERP was customized to incorporate commensurate reports to the excel based commitment accounting reports that were still being prepared at the margins: . . .Boom, boom, boom. All of a sudden it just happened like overnight. They had a working group that very quickly went into designing a customized system. . .We identied the issue, we got a very small group who really knew what they wanted to design, we rened that design. . .and then got the resources targeted to work on it. . .and its a done deal within two months time. . ..I guess thats a very good example of us starting to listen to end user needs realizing that we needed commitments I mean at rst we talked to the faculty and staff and said well what if we create a [time-phased budgeting] report where we massaged it here and massaged it there? and nally [we] woke up and said you know, as much as we try, its really not going to work, were trying to go around the issue rather than facing it head on. We nally did face it. [Academic manager, spring 2000] The customized ERP application was added to Ivys nancial management module and was internally marketed as a user-friendly solution with a web-based interface. While the staff found the custom application functionality to be clunky and frustrating as compared to their commitment accounting system, the web-based interface was easy to navigate and they were glad to have commitment data available through the ERP. Ivys management accounting information had drifted back to the point where it was imitating what it had been prior to the ERP implementation. Staff began to download commitment data from the ERP, importing the data into excel to reproduce what looked and felt like commitment accounting faculty reports. These material arrangements supported heterogeneous management accounting practices while still enabling central accounting to download, interpret and use accounting data from within the ERP. In addition to software modications, two local administrative support centres were created by Central Leadership to help solve problems faculty were facing including a Business Support Center (BSC), and a Trans-

action Support Center (TSC). The three BSC staff were required to evaluate the validity of departmental transactions, eliminate the need to make post-hoc accounting corrections and were expected to act as a control mechanism to enable a smooth ow of data into the ERP. The TSC staff comprised four ERP specialists each with a primary area of concentration but all cross-trained so that they could cover for one another. Two of the four specialists concentrate on accounting functionality. One of them acts as a liaison between Ivys old chart of accounts and the projectcentric chart, speaking with science-based administrators and clerical workers helping them to make the connection between the legacy and ERP environments. The other nancial specialist is concerned with processing accounting transactions she receives from the departments. These entries include grants management and labour distribution transactions that are central to the new time-phased budgeting approach. Despite the dismay of Central leadership, this administrative support was well-received and used by the departments especially when the accounting information that was required was for those decisions that were infrequently made. Ivys wealthier professional schools such as Medicine chose not to use these administrative support centres, but instead designed their own, very similar support mechanisms. The Medical School instituted a Business Center where staff are responsible for answering questions, understanding and interpreting policies, procedures, and then interpreting the project-centric chart of accounts. One central administrator called these administrative add-ons, Ivys fully trained temp agency [summer 2000] designed to assist faculty support staff whose responsibilities had increased in the ERP-enabled environment. An academic manager involved on the project describes the creation of the TSC: So I recommended that there be some type of a support center for giving departments a crutch. . .We thought modernization it should be quicker. Well I think the question has to be asked, quicker for whom?. . .what used to be a faculty appointment form became 25 screens of entry. . .there was a real need for having this place where they could just handle a lot of these transactions until we came up to speed. At least that was my argument cause I knew [they] werent going to go for something on a permanent basis. So I said, lets try six months. . .we quickly went forward and brought the [Centers manager] on board and then we staffed it and its really taken off. [summer 2000] In spite of agreeing to such modications, and implementing them quickly, the project team was unsupportive of the centres. The project team wanted to discourage further systems from being developed at the margins and avoid complexity at migration time. Second, they wanted the support centres to be viewed as a temporary part of Ivys culture that would be disbanded when the team managed to convince faculty of the value of fully migrating to the standard ERP. Despite the contentious nature of the Centres, their staff were regularly praised by a coalition of faculty and their support staff and their responsibilities increased. These organizational changes were instrumen-

192

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

tal in legitimizing faculty interests because the structures enabled the more time-consuming process of ERP-based grants management to be viable for academic constituencies. Meanwhile, the project team was still trying to convince the academic constituencies of the long-term value of the time-phased budgeting logic, which was a prerequisite for acceptance of the standard conguration and the subsequent creation of their preferred integrated budget and planning environment. In an attempt to do this, three central administrative units merged and formed the Accounting & Budget Department, which integrated the Controllers ofce (including accounting and nance ofces) with the Budget and Planning department. This consolidation was considered long overdue and it was hoped that by breaking down silos of central administrative practice, faculty might nally hear a unied voice espousing the virtues of time-phased budgeting practices. This department issued a procedure for academic staff conducting monthly nancial reconciliations that was focused on high-level nancial review rather than detailed book keeping activities that comprised commitment accounting. During this time many departments did begin to use the ERP more regularly: So in terms of whats happened between April and now? Weve worked a lot with departments theyve cleaned up a lot of problems that were persistent for the rst 6 months. . .I think most departments would tell you that they pretty much know where they are with their funds now and they wouldnt have told you that at the beginning of April. But theyd probably also tell you that they wouldnt like to do a year like this again. . .most of them are not interested in complaining for the sake of complaining, theyre interested in making things better. [Project leader, summer 2000] The recursive relationship between accounting practices, technologies and human agency exhibited above demonstrates a story of re-conguring, or better reguring, ERP, which we argue is not the exception to the rule but rather an accurate reection of the technology drifting and inevitable inconsistencies in management accounting practice. An ERP may scaffold practice, but drift will still exist within organizations. 4.5. Epilogue The customized commitment application combined with the ERPs original conguration eventually allowed the system to work across departments and faculty were able to get the information they required to optimize the use of their grants. There was agreement that the reconguration of the system, which enabled it to mirror the legacy practices, provided a better reection of the nancial position of the PIs projects and was seen to contribute to reducing the institutional risk. In 2008, time-phased budgeting was however still a non-starter and the most Ivy leadership had been able to do was encourage faculty and their staff to enter some budget gures into the ERP system for all grants thereby enabling all-funds budgeting at the institutional level. Even Ivys senior leadership had shifted

their opinions of this form of accounting as the following quote from the Director of Financial Planning suggests: Were still struggling with the commitment vs. projection [time-phased budgeting] approach. . .We have been successful. . .in having them pull the automated commitments from the system on the last day of the month, and combine those with actuals and projections. That way they can at least take advantage of the [ERP] system functionality related to budgeting and planning. Many departments are doing this, but I think they often manually supplement the information with other commitments they cant get automatically and create Excel reports for their faculty. As far as the time-phased approach goes, that is pretty much a non-starter here. I dont even support it myself. Administrators have taken on the responsibility of downloading the commitment data for each PI and they import this into excel to create custom PI reports. This process means the nancial transactions are recorded in duplicate in two systems: the ERP and their shadow systems. The expected cost savings of transferring the ownership of grants management to faculty did not occur. Instead Ivy has incurred additional costs to support the newly created Centres. Furthermore, since going live the ERP has been upgraded on several occasions and while this has been a somewhat more costly exercise than was anticipated in purchasing the system because of the bolton nature of the ERP reconguration, Ivy budgeted for the additional expense and time that was necessary: The only impact for an upgrade is to do testing of the processes. In general I dont recall any changes introduced during an upgrade that created any problems with these processes. We have to perform impact analysis and testing for all of the major processes in the system, so this is just part of that mix. [Spring 2010] In 2010 senior management reported that time-phased budgeting had been adopted at Ivy: Finally, after 10+ years, time-phased budgeting is now being done. We just started [reinstating the approach] when the US nancial crisis began and we needed to cut expenses across the board and more carefully monitor spending. The administration used this nancial situation to leverage time-phased budgeting. They argued that more careful monitoring of cash ows month-bymonth and budgeting monthly was necessary. . .It is not that faculty are more receptive, it is just that the climate is different. [Spring 2010] These changes demonstrate the evolution of sociomaterial assemblages including accounting practices. While bolt-ons prevent systems from collapsing, they do not themselves provide complete accounts and as such are subject to constant re-guring. While it is tempting to presume that migrating to new ERP versions are obvious occasions for discussing the absence/presence of particular accounting functions, we see at Ivy the commitment accounting legacy assets were reinstated across multiple upgrades legitimizing the bolted-onto ERP with the old ways of working. It was the need for the sociomaterial

E.L. Wagner et al. / Management Accounting Research 22 (2011) 181197

193

assemblage to respond to changing environmental conditions that eventually shifted the sociomaterial assemblage surrounding grant accounting at Ivy, at least temporarily. 5. Discussion Our case rst demonstrates, through a longitudinal eld study, the process of implementing so-called best practice ERP systems and their inuence on management accounting practices while at the same time illustrating how existing management accounting practices can inuence the ERP system. This empirical study when viewed through the key construct of sociomaterial practice provides rich insight into existing literature that has reported on standardized information architectures and inexible accounting logics of enterprise software. Our theoretical explanation moves beyond the simple attribution of change to either human or technical agency (i.e., underor over-socialized accounts) to produce a more compelling theoretical explanation of the way in which a working information system emerges through negotiations around processes of use. Second, we provide a theoretical explanation for what happens between people and their technology tools when the ERP is in production and users are working in the new environment. Through the key construct of reconguration we were able to focus on how persons and things might be gured together differently when resistance is encountered to a new sociomaterial arrangement following ERP implementation. We found that supplementing, and so changing, the best practice design is a viable and valuable tool for creating a working information system and that indeed sociomaterial assemblages evolve over time, always subject to redenition. Third, we contribute to accounting literature by extending knowledge on how software-based accounting tools might work effectively within an organization. The construct of relationality helped explain why multiple practice communities that exist across the eld of accounting within an organization will likely be at odds. These different communities will have more or less power to inuence the sociomaterial practices surrounding an ERP conguration/reconguration and this can change over time. For instance, it was the Economics Professors position of Provost and his prior held position as VP Finance and Administration that enabled him to have some inuence over the negotiations regarding the reinstatement of commitment accounting. In a similar vein, the wealthy status of professional schools such as Medicine had enabled them to design their own support mechanisms for commitment accounting. In sum, this study helps develop our understanding of the linkages between accounting, information technology and integrated administrative systems like ERP that are widely used in contemporary organizations. We discuss each of these issues next. 5.1. Sociomaterial practice Normative accounting literature has treated technology as an absent presence, neglecting to consider the materiality that these types of architectures provide in the practice

of accounting. When materiality is taken into account, a unidirectional relationship is theorized whereby the focus has been to understand the impact of ERP-systems on accounting through either privileging IT in explaining the form of accounting, or the reverse: emphasizing management accountings impact on IT development/modication. The sociomaterial perspective demonstrates how an ERP can be enacted in different ways as it connects with practices of different communities of users (Law and Singleton, 2005). Nevertheless, this differential enactment has limits created by the material conguration. In Ivy, the best practice was dened by professional accountants from the central administration who encoded accounting logics that suited their particular interests related to institutional risk. In doing this, the needs of the distributed faculty who had not been professionally trained to manage their project budgets and moreover, had different interests compared to the central accountants (i.e., to spend all their budget in the interests of their research projects vs. to reduce institutional risk) were ignored. This led to post-implementation negotiations, and our analysis shows how an accounting system can be made functional as different communities resist and accommodate the best practices (Pickering, 1993) until eventually a recongured system is created that includes valued functionality that allows different communities to accommodate their needs. Demonstrating this recursive relationship between accounting practices, technologies and its users contributes to the recent call in the management accounting literature for further longitudinal studies of accounting that examine in-depth the bidirectional nature of the relationship between management accounting and ERP technologies (see Rom and Rohde, 2007; Luft and Shields, 2003). The detailed Ivy case contributes to our understanding of how working accounting information systems are created around an ERP. We have shown that accounting is not an object in its own right but is better seen as a set of practices that are scaffolded by material objects (e.g., ERP) that are used by diverse communities to perform different tasks. Quattrone and Hopper (2006) thus describe ERP as being heteromogeneous in the sense that they appear to be homogeneous precisely because they are actually heterogeneous, providing a space whereby users can experiment with them and create different sociomaterial assemblages. However, given the integrated nature of an ERP, the freedom to experiment through practice may be more limited than is suggested by this concept. Performability is restricted by the best practice logic that has been initially congured in the ERP. In Ivy this set the stage for negotiations which lead to recongurations that accommodated diverse practices, with these diverse practices and interests exposed rather than concealed by the ERP. In accommodating these diverse interests the ERP was recongured in such a way that the legacy management accounting practice was reinstated. At face value this seems to reinforce the ndings by Granlund and Malmi (2002) that ERPs have little impact on management accounting practice and answer their question as to whether this minimal impact was because practice change lags implementation (they looked only at companies who had very recently introduced an ERP) in the negative. However, this obscures the

194