Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Fraseado PDF

Hochgeladen von

dionatan_dspOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Fraseado PDF

Hochgeladen von

dionatan_dspCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Loco Motion - 02/2002

By Dickey Betts

The Art of Phrasing

I'd like to start this column by saying a few things about the importance of phrasing. Phrasing is, simply, the way in which a melody is articulated. Phrasing a melodic line properly entails things like the loudness or softness of each note in the lick, and where each note sits in relation to the beat-behind the beat, ahead of the beat or square on the beat-as well as every possible aspect of how a melody line is "spoken" on the instrument. On the guitar, articulation includes the use of bends, slides, hammer-ons, pull-offs, a combination of all or picking each note individually. I've always drawn a close correlation between guitar lines and vocal lines because the same musical e lements come into play whether one is singing a line or playing it on the guitar. One aspect common to both instruments that comes to mind is "scooping" into a pitch: when singing a melody, it's not uncommon to sing a note by starting a bit below the "target" pitch and gliding up to it. On the guitar, we can emulate this scooping sound by bending a string. When I bend notes, I tend to play behind the beat a little bit. I'll start a fret or two below the pitch I want, and I'll bend up to the note so that the desired pitch comes in just behind where the downbeat falls. To me, this gives the guitar line more feeling and emotion than you get when you play right on top of the beat or in front of the beat. (When playing at a fast tempo, you'd want to play in front of the beat a little.) To hear what I mean, try playing the examples shown in FIGURES 1a and 1b.

Figure 1A MP3 Figure 1B MP3 In FIGURE 1a, each bend falls squarely on the beat; in FIGURE 1b, the bends are purposely played behind the beat. Experiment with this idea using bending licks of your own.

Another important factor in phrasing is the use of vibrato. More than any other factor, a good vibrato can really give a guitar line a nice vocal feel. To begin developing a controlled vibrato, start by fretting any note on the guitar and pick it using no vibrato whatsoever. Then, add a slight amount of wrist vibrato by holding the note firmly with the tip of the finger, anchoring the edge of the fretting hand against the bottom side of the neck and rocking the wrist back and forth in a steady, even manner to bend the string slightly. Whether you're bending and releasing the note slowly, quickly or somewhere in between, strive to keep the sound of the vibrato even and uniform. Then, try the same thing using bent notes. The result is definitely worth the effort, though, as this is one of the most pleasing kinds of vibrato on the guitar. Another type of vibrato forearm vibrato: after a note is fretted, the forearm and wrist are held stiff and the entire arm shakes back and forth, essentially using the weight of the guitar for leverage. When using this type of vibrato, leave some space between the palm of the fretting hand and the back of the neck. Again, try using different speeds with this type of vibrato. Let's take a deeper look into phrasing ideas using the six-note hexatonic scale that I outlined in last month's column. FIGURE 2 illustrates the A major hexatonic scale (A B C# D E F#) in the fourth position. I like to think of the major hexatonic as my "major" scale because it's a scale I use often when soloing over major chords. The A major hexatonic scale is essentially the A major scale (A B C# D E F# G#) without the seventh, G#.

Figure 2 MP3 Another way of approaching this scale is through the use of its relative minor. If I'm playing in the key of A, I'll shift down three frets to the relative minor, F#, and play F# minor pentatonic with the inclusion of D, the minor, or "flat," sixth. FIGURE 3 illustrates how these two scale patterns overlap each other. Using the relative minor scale in this way affords me another way of looking at the guitar neck when improvising. Figure 3 MP3 I don't think about any of these things when I'm actually improvising - I just let my ears lead the way! At this point, my playing has developed to the point where I naturally combine a variety of scale positions within any given solo. FIGURES 4a-c show different examples of how I'll connect A major hexatonic in the fifth position and its "relative minor" position three frets lower. Connecting scale positions in this way can really open up a lot of new creative ideas.

Figure 4A MP3 Figure 4B MP3 Figure 4C MP3 Next month, I'll demonstrate how to add chromatics to the mix. See you then. Visit Dickey Betts on the web at: DickeyBettsBand.com

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Jazz TheoryDokument82 SeitenJazz Theorytouchofclass56291% (47)

- Fingerstyle Guitar Tabs PDFDokument3 SeitenFingerstyle Guitar Tabs PDFTammy Mahoney9% (22)

- Speed Training BanjoDokument2 SeitenSpeed Training BanjoljnonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modern School For SaxophoneDokument23 SeitenModern School For SaxophoneAllen Demiter65% (23)

- 11.1.2 BGBanjoCherokeeShuffle 1Dokument1 Seite11.1.2 BGBanjoCherokeeShuffle 1ENoch keine Bewertungen

- Dick Dale - MisirlouDokument10 SeitenDick Dale - MisirlouIvano100% (1)

- Instrument String Gauges and Tuning ChartDokument1 SeiteInstrument String Gauges and Tuning ChartRyeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Bass in Latin America Peruvian GroovesDokument3 SeitenThe Bass in Latin America Peruvian GroovesIsrael Mandujano Solares100% (1)

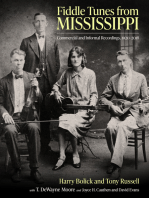

- Fiddle Tunes from Mississippi: Commercial and Informal Recordings, 1920-2018Von EverandFiddle Tunes from Mississippi: Commercial and Informal Recordings, 1920-2018Noch keine Bewertungen

- FLP10078 Norway FiddleDokument9 SeitenFLP10078 Norway FiddletazzorroNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To Turn A Regular Fiddle Into A Hardanger FiddleDokument2 SeitenHow To Turn A Regular Fiddle Into A Hardanger FiddlepiomarineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Graná Session TunesDokument2 SeitenGraná Session TunesDavid Cáceres Gallardo0% (1)

- BB KingDokument7 SeitenBB Kingyassinovic005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Journal of The Folk Song Society No.12Dokument102 SeitenJournal of The Folk Song Society No.12jackmcfrenzieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Major TriadsDokument10 SeitenMajor Triadsbuendiainside100% (1)

- BLUES DominationDokument25 SeitenBLUES DominationAlessandro ValentimNoch keine Bewertungen

- CharliePoole HighWide&HandsomeDokument37 SeitenCharliePoole HighWide&HandsomehugoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Uke Improv 4-08Dokument0 SeitenUke Improv 4-08Leila MignacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diminished Scale VibesDokument3 SeitenDiminished Scale VibesMartin HemingwayNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1001 PDF BookletDokument7 Seiten1001 PDF BookletBrandon NewsomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interview Michael BorremansDokument4 SeitenInterview Michael BorremansDejlKuperNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voice of The MandolinDokument2 SeitenVoice of The MandolinAleph PilgerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Custom Inlay - An Ancient Art Form Reimagined by Juha Ruokangas PDFDokument1 SeiteCustom Inlay - An Ancient Art Form Reimagined by Juha Ruokangas PDFWilliam PacatteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalogue of Musical Instruments Plates StringedDokument86 SeitenCatalogue of Musical Instruments Plates Stringedvendorchile100% (2)

- The Cosmic American: Harry Smith's Alchemical ArtDokument11 SeitenThe Cosmic American: Harry Smith's Alchemical ArtWilliam RauscherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hot Licks For Bluegrass Tenor Banjo: by Mirek PatekDokument9 SeitenHot Licks For Bluegrass Tenor Banjo: by Mirek PatekMirek Tim PátekNoch keine Bewertungen

- G Dominant 7 R&B Jam RhythmDokument2 SeitenG Dominant 7 R&B Jam RhythmOkta NapithNoch keine Bewertungen

- Violin BridgeDokument1 SeiteViolin BridgeFramos JestesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gourd Banjo Construction PDFDokument16 SeitenGourd Banjo Construction PDFjoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Easy Tips For Killer Blues TonesDokument7 Seiten5 Easy Tips For Killer Blues Tonesdachi tavartkiladzeNoch keine Bewertungen

- SessionWithTheStars TedGreeneHandout SheetsDokument10 SeitenSessionWithTheStars TedGreeneHandout SheetsYuri CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chord Forms For Cigar Box Guitar G BluesDokument8 SeitenChord Forms For Cigar Box Guitar G Bluesjaumett100% (1)

- Improvised Folk FiddleDokument16 SeitenImprovised Folk FiddleEd NunezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Junior A 2014Dokument8 SeitenJunior A 2014Raditya Ardianto TaepurNoch keine Bewertungen

- 420 618 GoDownMoses PDFDokument4 Seiten420 618 GoDownMoses PDFJenrryGiovanyVenturaDiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Plectrum Guitar Website Examples PDFDokument11 SeitenPlectrum Guitar Website Examples PDFAlotta PhagynaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hourglass Mountain Dulcimer: Musicmaker's KitsDokument12 SeitenHourglass Mountain Dulcimer: Musicmaker's KitsKen WilkmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ed Sheeran - I See FireDokument5 SeitenEd Sheeran - I See FireJovelina NóbregaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Beatles Atestat Alex 3.Dokument13 SeitenThe Beatles Atestat Alex 3.Alexandra Daramus100% (1)

- Program Notes French SuiteDokument2 SeitenProgram Notes French Suitewaterwood3388Noch keine Bewertungen

- Guitar Legato Playing PDFDokument3 SeitenGuitar Legato Playing PDFLuis G. SoriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Djembe Pattern Embellishment PDFDokument4 SeitenDjembe Pattern Embellishment PDFPercusion Gustavo MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iron Maiden - 2 Minutes To MidnightDokument7 SeitenIron Maiden - 2 Minutes To MidnightHermes AlcioneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Iron Maiden - Dance of DeathDokument9 SeitenIron Maiden - Dance of DeathHermes AlcioneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Angelo ConcertinaDokument4 SeitenAngelo Concertina蔡偉靖100% (1)

- Bluestem Mandolin Information PDFDokument7 SeitenBluestem Mandolin Information PDFpablo penaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Stella by Starlight - Uke Chord Melody ArrangementDokument2 SeitenStella by Starlight - Uke Chord Melody ArrangementRich RobergeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Power of Triads2 JJGDokument3 SeitenThe Power of Triads2 JJGJacob SinclairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rory Block - I Belong To The Band: A Tribute To Rev. Gary Davis (Liner Notes)Dokument6 SeitenRory Block - I Belong To The Band: A Tribute To Rev. Gary Davis (Liner Notes)Stony Plain RecordsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bowling Green Bowling Green Bowling Green Bowling Green: A F#M A F#MDokument1 SeiteBowling Green Bowling Green Bowling Green Bowling Green: A F#M A F#Mmartzo-100% (1)

- Chord Ideas & 16th Note StrumsDokument6 SeitenChord Ideas & 16th Note StrumsPoss HumNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malaguena - Third Day Lesson: Am C7 F DM ADokument5 SeitenMalaguena - Third Day Lesson: Am C7 F DM ARailson da LuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guitar Pedal SettingsDokument4 SeitenGuitar Pedal SettingsMatt JamesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lampros Efthymiou Τhe LavtaDokument8 SeitenLampros Efthymiou Τhe LavtaNatural AssemblyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lino TuneDokument8 SeitenLino TuneAnonymous Wyb8Y1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lonesome Pine Mandolin Intermediate Tab OnlyDokument1 SeiteLonesome Pine Mandolin Intermediate Tab OnlycechuraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guitar Theory Pentatonic Scales IIDokument3 SeitenGuitar Theory Pentatonic Scales IIBrettNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparison of Arching Profiles of Golden Age Cremonese Violins and Some Mathematically Generated CurvesDokument18 SeitenComparison of Arching Profiles of Golden Age Cremonese Violins and Some Mathematically Generated Curvesnostromo1979Noch keine Bewertungen

- American Mando-Bass History 101: by Paul RuppaDokument8 SeitenAmerican Mando-Bass History 101: by Paul RuppadosilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- RGFL 001tabs PDFDokument4 SeitenRGFL 001tabs PDFSandeep TuladharNoch keine Bewertungen

- musicNotationBass PDFDokument1 SeitemusicNotationBass PDFDesarrollando Tu MusicalidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sarasateand His Stradivari Violins PDFDokument11 SeitenSarasateand His Stradivari Violins PDFMax RakshaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abcdebfgbab: A Arabian ScaleDokument5 SeitenAbcdebfgbab: A Arabian ScaleEdilson SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guitar Buyer Ozark Deluxe ResoDokument3 SeitenGuitar Buyer Ozark Deluxe ResoAndy GearNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Ideas For Beginning Level Guitar Class - Teaching Guitar Workshops - The Guitar EducationDokument4 SeitenAssessment Ideas For Beginning Level Guitar Class - Teaching Guitar Workshops - The Guitar EducationTracy WayneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Don't Start Me Talkin': Chris SmithDokument6 SeitenDon't Start Me Talkin': Chris SmithGaurav DharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Using Gamaka To Add Indian Flavor To Your Guitar PlayingDokument8 SeitenUsing Gamaka To Add Indian Flavor To Your Guitar Playingtrancegodz100% (1)

- Brownie McGheeDokument3 SeitenBrownie McGheebillNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catalogo Banjo PDFDokument166 SeitenCatalogo Banjo PDFIsrael Esquivel MartinezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Performing Englishness: Identity and politics in a contemporary folk resurgenceVon EverandPerforming Englishness: Identity and politics in a contemporary folk resurgenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Union PipesDokument116 SeitenUnion PipesJosé Miguel Mazdy100% (1)

- Breathe: Words & Music by Marie BarnettDokument13 SeitenBreathe: Words & Music by Marie Barnettalexandertrujillo519Noch keine Bewertungen

- Folk DanceDokument6 SeitenFolk DanceThea Morales-TrinidadNoch keine Bewertungen

- ModesDokument3 SeitenModesAndy TothNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wishbone Ash-Outward BoundDokument3 SeitenWishbone Ash-Outward BoundPaul OwenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Not Alone Anymore: by Traveling WilburysDokument2 SeitenNot Alone Anymore: by Traveling WilburysIlyés-Nagy Zoltán És BoglàrkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oceans Where Feet May Fail CordasDokument14 SeitenOceans Where Feet May Fail CordasAnne KarolyneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mrs Curwen - Piano Step 1Dokument25 SeitenMrs Curwen - Piano Step 1Yellow FlowersNoch keine Bewertungen

- NIETZSCHE Y BRAHMS - Una Relación OlvidadaDokument21 SeitenNIETZSCHE Y BRAHMS - Una Relación OlvidadaacaromcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Folk Dances of India Ef370892Dokument3 SeitenFolk Dances of India Ef370892Swapnil Saner100% (1)

- Suite Nello Stile Italiano by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Review By: James Ringo Notes, Second Series, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Jun., 1957), P. 445 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 07/10/2014 09:14Dokument2 SeitenSuite Nello Stile Italiano by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco Review By: James Ringo Notes, Second Series, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Jun., 1957), P. 445 Published By: Stable URL: Accessed: 07/10/2014 09:14Angelo LippolisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Concert Invitation Report PDFDokument2 SeitenConcert Invitation Report PDFyunitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Is Known As TheDokument6 SeitenWho Is Known As TheJason Dave LeybleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oficina G3 - Ele ViveDokument8 SeitenOficina G3 - Ele ViveWagner Alves do NascimentoNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdeleDokument15 SeitenAdeleSawbil FajarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Call Me MaybeDokument2 SeitenCall Me MaybeAlena DoricoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ate Rich - Thai InstrumentsDokument2 SeitenAte Rich - Thai InstrumentsChel RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Xenoblade Main ThemeDokument3 SeitenXenoblade Main ThemeklaverundervisningNoch keine Bewertungen