Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Tourists Perceptions of World Heritage Site and Its Designation

Hochgeladen von

xohaibaliCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tourists Perceptions of World Heritage Site and Its Designation

Hochgeladen von

xohaibaliCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tourism Management 35 (2013) 272e274

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Tourism Management

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tourman

Research note

Tourists perceptions of World Heritage Site and its designation

Yaniv Poria*, Arie Reichel 1, Raviv Cohen 2

Department of Hotel and Tourism Management, Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, P.O. Box 653, Beer-Sheva 84105, Israel

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history: Received 9 November 2011 Accepted 23 February 2012 Keywords: World heritage World Heritage Site Designation

a b s t r a c t

This exploratory study claries visitors perceptions, meanings and conceptualizations associated with the World Heritage Site designation. In-depth open as well as semi-structured interviews were conducted with 57 participants. The ndings indicate that WHS designation has several effects relevant to the understanding of the concept of world heritage, and visitors experiences at such sites. The ndings implications are discussed in terms of both theory and practice. 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction Studies focusing on visits to World Heritage Sites (WHS) or UNESCOs designation process seldom relate to visitors perceptions of the designation. This research gap is surprising since studies indicate that WHS designation often results in an increase in demand patterns and tourist inux (Tucker & Emge, 2010; Yang, Lin, & Han, 2010). Moreover, the designation is perceived as branding (Timothy, 2011) or labelling (Yang et al., 2010), a process to which positive attitudes are assigned. The designation is considered important especially when attempting to create a cultural image associated with a site (Ung & Vong, 2010). The rationale for exploring the meanings visitors assign to the designation also relies on studies emphasizing its impact on other stakeholders. For example, van der Aa, Groote, and Huigen (2005) speculate that on-site employees gain a sense of pride from a WHS designation and also engaging volunteers becomes an easier task. It has also been noted that a WHS designation instills a great sense of pride among the regions residents (Jimura, 2011). Based on the above studies, as well as research on the subjective symbolic meaning of a heritage site and its effect on the tourist experience (e.g. Winter, 2002, 2007) it is hypothesized that the WHS designation may have an impact on the visitors perceptions of the site, its display and the on-site experience.

2. Method Utilizing the experientially based approach, this study focuses on the visitors and their perceptions. In line with the exploratory nature of this study, a qualitative methodology was adopted. Fiftyseven semi-structured interviews were conducted with international (n 15) and domestic (n 32) tourists in Israel. In order to enrich and validate the data, interviews were conducted with practitioners involved with heritage tourism. These in-depth open interviews included tour guides (n 2), travel agents (n 3) as well as professionals (n 5) who work and manage heritage tourism sites. For diversity purposes, the interviews took place at several locations in Israel. The interviews with the tourists were conducted while they were involved in tourism activities. The participation rate was 70% (non-response was attributed to time constraints). The interviews were recorded after participants granted permission. Topics included the nomination process, the meanings assigned to the designation and possible impacts of the WHS designation on the visit experience. Participants were asked in an open question to list designated sites around the globe as well as additional sites that should be considered as potential candidates for nominations. Furthermore, they were introduced to a list of heritage sites and requested to choose sites that should be designated as WHS. Each choice required an explanation while attempting to capture the meaning that participants assign to world heritage. Interviewees were also asked about the possible effects of a WHS designation on the visit experience. The data analysis identied main themes and possible links between them. At this stage, the researchers reected on their positioning as active learners rather than experts. Data analysis was straightforward in the sense that the researchers achieved a high level of agreement on the emergent themes.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 972 8 6479737; fax: 972 8 6472920. E-mail addresses: yporia@som.bgu.ac.il (Y. Poria), arier@som.bgu.ac.il (A. Reichel), rcohen@som.bgu.ac.il (R. Cohen). 1 Tel.: 972 8 6472229; fax: 972 8 6472920. 2 Tel.: 972 8 6479737; fax: 972 8 6472920. 0261-5177/$ e see front matter 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2012.02.011

Y. Poria et al. / Tourism Management 35 (2013) 272e274

273

3. Results The analysis revealed several ndings, some of which relate to the visit experience while others to the designation itself and specically, to the conceptualization of world heritage. As far as the latter is concerned, participants associated the concept World Heritage Site with a culturally famous site of major signicance to humankind. The concepts of culture and signicance to humankind were identied by almost all interviewees as prerequisites for a WHS designation. The paramount role of signicance to humankind was reected in the participants argument that a WHS designation should be bestowed only upon signicant multi-cultural, multi-national or multi-religious sites. For example, a predominantly Jewish, Christian or Moslem site should not be designated as WHS unless considered signicant and cherished by the other religions as well. Moreover, participants claimed that some of the currently designated WHSs should not have been granted the designation status since they are neither perceived as part of a particular groups heritage nor as part of the worlds heritage. For example, Israeli participants suggested that some of the WHSs located in Israel are of no cultural importance to humankind. Additionally, participants argued that a WHS designation nominee need not be required to be ancient or objectively authentic. Interviewees also highlighted that authentic remains are not required to be presented at the site. For example, participants referred to Ground Zero as a potential site for WHS designation, in spite of the fact that most of its ruins were removed. They also indicated that a WHS site is not required to be located in situ of the specic events it represents. Some interviewees, for example, referred to Holocaust museums located in different cities around the world to exemplify their view. Clearly, the ndings highlight peoples perceptions and feelings about the site rather than the sites attributes per se. UNESCO designated a substantial number of natural sites as WHS (of the total 936 properties designates as WHS 183 are natural). Respondents rarely agreed that natural sites should be considered as World Heritage. Apparently, they believed that nature does not relate to human heritage. When asked to suggest natural sites as nominees, participants rarely found appropriate candidates. Only a few participants suggested several natural sites as deserving a WHS designation. Among the natural sites, only famous, exceptionally beautiful and well-known tourist attractions such as Niagara Falls, the Grand Canyon and Yellowstone National Park were mentioned. Participants were also asked to refer to the designation process. The ndings indicate that most interviewees were not aware of the criteria or the designation process, except for the fact that the UN is the regulating body. Questions also related to the advantages and disadvantages of WHS designation. Indeed, the main advantage reported is an increase in the sites popularity resulting in more revenues. Participants were also aware of the fact that once a site is designated, no changes or alterations can be made. Additionally, participants mentioned that the price of housing may increase in areas of designated sites, given their growing prestige. Interviewees also assigned a sense of national and local pride to the designation. In spite of the potential increase in real estate value, most interviewees favored WHS designations as long as the site was not in their own backyards, preferring not to live near or within a WHS designated area. The major reason stated for reservations about living near a WHS was the fear of crowdedness due to tourism trafc. The second focus of this study is on the designations potential effects on the site as a tourist attraction. In this context, participants attributed the expected growth in tourism demand to the sites new

status as a national tourist highlight or a must visit attraction. They also suggested that the designation validates the signicance of the heritage presented. In the case when historic artifacts are presented, the designation seems to conrm their objective authenticity. The designation also serves as a global recommendation to visit and cherish the site. However, none of the participants recognized the WHS logo. Additionally, the interviewees believed the designation suggests that a site is well managed in terms of providing necessary services (e.g. toilets, transportation to the site). Participants also suggested that at designated sites the interpretation is more professional than at non-designated sites. In addition, reference was made to entrance fees, suggesting that due to the growth in demand entry fees will be higher in comparison to non-designated sites. 4. Conclusions The ndings contribute to both tourism theory and practice. With regard to theory, this exploratory study indicates that participants act in line with the experientially based approach that highlights the links between the individual and the displayed object. Indeed, the individuals perceptions and feelings toward the heritage presented (or demolished) are of considerable importance for a sites classication as world heritage. Similar to Mitchells (2001) contextualization, the current study indicates that the meanings of a heritage site rather than its objective attributes are essential for capturing the visitor attitudes toward the sites designation. Moreover, it was found that heritage is not required to be perceived as antique, in situ or original but rather be regarded as signicant to human culture. These ndings highlight the relationship between the physical and the imaginary realms of the tourist experience conceptualization (Knudsen, Soper, & MetroRoland, 2008). It is also congruent with the post modernist research epistemology that considers the tourist experience as a subjective concept. In addition, it conforms with environmental psychology literature in the sense that attitudes toward heritage and landscape derive from visitors cultural value system (Zube & Pitt, 1981) and their learning about the site (Knudsen et al., 2008). From an applied perspective, the ndings challenge the advantages usually assigned to WHS designation as a marketing resource. Not only were the interviewees unaware of the WHS logo, they also argued that some of the currently designated sites should not have been classied as such from the outset. Additionally, some of the designation impacts may have either a negative or no effect at all on the intention to visit a World Heritage Site. Specically, the ndings indicate that a designated site is perceived as more crowded and expensive than other historic sites. Although the designation is a signal for the importance and objective authenticity of the displayed heritage, it seems that the designation does not affect tourist demand. This nding may be explained by visitors interest in authentic on-site experiences rather than objective authenticity of the displayed heritage (Poria, Butler, & Airey, 2003). Moreover, the perception of the interpretation at designated sites as professional might inhibit the motivation of those seeking an emotional experience (see also: Poria, 2010). In spite of this exploratory studys relatively large sample size, it is impossible to determine its representativeness. Nevertheless, it seems that a site should be considered by visitors as relevant to humankind heritage in order to be perceived as world heritage. It should be noted, however, that peoples perception of a site as part of humankind heritage cannot be found on the UNESCO criteria list for the selection of sites to be nominated as WHS (UNSECO World Heritage Centre, 2011). Integrating the public perceptions into the designation process can be considered as an empowerment process, raising the credibility of WHS as a brand name.

274

Y. Poria et al. / Tourism Management 35 (2013) 272e274 Poria, Y., Butler, R., & Airey, D. (2003). The core of heritage tourism: distinguishing heritage tourists from tourists in heritage laces. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 238e254. Timothy, D. J. (2011). Cultural heritage and tourism: An introduction. Bristol: Channel View Publications. Tucker, H., & Emge, A. (2010). Managing a World Heritage Site: the case of Cappadocia. Anatolia, 21(1), 41e54. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. (2011). The criteria for selection. Available from http://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria Accessed 01.11.11. Ung, A., & Vong, T. N. (2010). Tourist experience of heritage tourism in Macau, China. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 5(2), 157e168. Winter, T. (2002). Angkor meets Tomb Raider: setting the scene. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 8(4), 323e336. Winter, T. (2007). Landscape in the living memory: New Year festivals at Angkor, Cambodia. In N. Moore, & Y. Whelan (Eds.), Heritage, memory and the politics of identity: New perspectives on the cultural landscape (pp. 133e147). Aldershot: Ashgate. Yang, C.-H., Lin, H.-L., & Han, C.-C. (2010). Analysis of international tourist arrivals in China: the role of World Heritage Sites. Tourism Management, 31(6), 827e837. Zube, E. H., & Pitt, D. G. (1981). Cross-cultural perceptions of scenic and heritage landscape. Landscape Planning, 8, 69e87.

Future research, including the design of a series of small-scale studies, would contribute to further clarication of the effects of WHS designation. For example, exploring the designation effects on visitors on-site behaviors such as readiness to wait on the sites entrance line. Based on conclusions derived in environmental psychology on intercultural differences in the perception of heritage landscape (i.e. Zube & Pitt, 1981) future studies should clarify cross-cultural attitudes toward the designation. Given the differences between sites in terms of social roles and symbolic meanings (Winter, 2007), site-specic studies about the designation impacts are recommended. Such studies will enrich our understanding of the signicance of visitors site perception (Knudsen et al., 2008). References

van der Aa, B. J. M., Groote, P. D., & Huigen, P. P. P. (2005). World heritage as NIMBY? The case of the Dutch part of the Wadden Sea. In D. Harrison, & M. Hitchcock (Eds.), The politics of world heritage: Negotiating tourism and conservation (pp. 11e21). Clevedon: Channel View. Jimura, J. (2011). The impact of World Heritage Site designation on local communities e a case study of Ogimachi, Shirakawa-mura, Japan. Tourism Management, 32(2), 288e296. Knudsen, D. C., Soper, A. K., & Metro-Roland, M. M. (2008). Landscape, tourism and meaning: an introduction. In D. C. Knudsen, A. K. Soper, M. M. Metro-Roland, & C. E. Greer (Eds.), Landscape, tourism and meaning (pp. 1e18). Aldershot: Ashgate. Mitchell, D. (2001). The lure of the local: landscape studies at the end of a troubled century. Progress in Human Geography, 27(6), 787e796. Poria, Y. (2010). The story behind the pictures: preferences for the visual display at heritage sites. In E. Waterton, & S. Watson (Eds.), Culture, heritage and representation (pp. 217e228). Surrey: Ashgate.

Yaniv Poria is an Associate Professor in the Department of Hotel and Tourism Management at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. He holds a Ph.D. in Heritage Tourism Management from Surrey University. His main research interest is the management of heritage in tourism.

Arie Reichel holds a Ph.D. in Business Administration from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. His research areas include tourism marketing and management.

Raviv Cohen is a graduate of the Department of Business Administration in the Guilford Glazer Faculty of Business and Management at Ben-Gurion University. His main research interest is the management and marketing of World Heritage Sites.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Ses18c-2a QABF Questions About Functional Behavior Rev BDokument2 SeitenSes18c-2a QABF Questions About Functional Behavior Rev Bevanschneiderman67% (6)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Math Problem Solving in Action - Getting Students To Love Word Problems, Grades 3-5 PDFDokument188 SeitenMath Problem Solving in Action - Getting Students To Love Word Problems, Grades 3-5 PDFOliveen100% (5)

- ADDC RegulationDokument18 SeitenADDC RegulationLester Bencito75% (4)

- 02-Leed Core Concepts GuideDokument125 Seiten02-Leed Core Concepts GuideOsama M Ali100% (4)

- Guide to Achieving 1 Pearl Rating for BuildingsDokument72 SeitenGuide to Achieving 1 Pearl Rating for Buildingswaboucha100% (2)

- Guide to Achieving 1 Pearl Rating for BuildingsDokument72 SeitenGuide to Achieving 1 Pearl Rating for Buildingswaboucha100% (2)

- ECO ListDokument10 SeitenECO Listxohaibali0% (1)

- True Rating SystemDokument58 SeitenTrue Rating SystemxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contractors SustainabilityDokument26 SeitenContractors SustainabilityxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Site Plan PDFDokument1 SeiteSite Plan PDFxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pearl Community Rating System Guide for Design & ConstructionDokument182 SeitenPearl Community Rating System Guide for Design & ConstructionelmerbarrerasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specimen For Solar Water HeaterDokument12 SeitenSpecimen For Solar Water HeaterxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- EstidamaDokument138 SeitenEstidamajohnknight000Noch keine Bewertungen

- CDD - Waste EstimatesDokument2 SeitenCDD - Waste EstimatesxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Municipal Solid Waste PDFDokument234 SeitenMunicipal Solid Waste PDFramadugula_v50% (4)

- 1-Estidama Audit PRocessDokument13 Seiten1-Estidama Audit PRocessxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Site Plan PDFDokument1 SeiteSite Plan PDFxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- LBo R2 Sarooj MosqueDokument4 SeitenLBo R2 Sarooj MosquexohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sustainability Consultant JD Alpin Limited 1.2013Dokument3 SeitenSustainability Consultant JD Alpin Limited 1.2013xohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- MOM-ESTIDAMA Requirements & Final Deliversbles PDFDokument2 SeitenMOM-ESTIDAMA Requirements & Final Deliversbles PDFxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candidate Application FormDokument1 SeiteCandidate Application FormxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roof DetailsDokument1 SeiteRoof DetailsxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pages From NS-R3Dokument4 SeitenPages From NS-R3xohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Composition of Waste Disposed of by The UK Hospitality Industry FINAL JULY 2011 GP EDIT.54efe0c9.11675Dokument129 SeitenThe Composition of Waste Disposed of by The UK Hospitality Industry FINAL JULY 2011 GP EDIT.54efe0c9.11675xohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specimen For Change in AeratorDokument1 SeiteSpecimen For Change in AeratorxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waste Management Eng Art1Dokument4 SeitenWaste Management Eng Art1xohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specimen of Dubai Central LaboratoryDokument2 SeitenSpecimen of Dubai Central LaboratoryxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- SamplingDokument178 SeitenSamplingRajesh RajaramNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manto Ke 100 Behtreen Afsane CH1Dokument230 SeitenManto Ke 100 Behtreen Afsane CH1Fahad AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abu Dhabi Public Realm Design ManualDokument4 SeitenAbu Dhabi Public Realm Design ManualxohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Atlas of Abu DhabiDokument1 SeiteEnvironmental Atlas of Abu DhabixohaibaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information Bulletin 3 Building Def Rev3Dokument1 SeiteInformation Bulletin 3 Building Def Rev3Alan TanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Islamic Arabic Prose Literature & Its GrowthDokument145 SeitenPre-Islamic Arabic Prose Literature & Its GrowthShah DrshannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Software Engg. Question Paper - 40 CharacterDokument14 SeitenSoftware Engg. Question Paper - 40 Characteranon_572289632Noch keine Bewertungen

- CvSU Org ChartDokument3 SeitenCvSU Org Chartallen obias0% (1)

- 15 05 2023 Notification Ldce SdetDokument3 Seiten15 05 2023 Notification Ldce SdetPurushottam JTO DATA1100% (1)

- Carl Dahlhaus, "What Is A Fact of Music History "Dokument10 SeitenCarl Dahlhaus, "What Is A Fact of Music History "sashaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shabnam Mehrtash, Settar Koçak, Irmak Hürmeriç Altunsöz: Hurmeric@metu - Edu.trDokument11 SeitenShabnam Mehrtash, Settar Koçak, Irmak Hürmeriç Altunsöz: Hurmeric@metu - Edu.trsujiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Step-By-Step Analysis and Planning Guide: The Aira ApproachDokument5 SeitenStep-By-Step Analysis and Planning Guide: The Aira ApproachDaniel Osorio TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- General Financial Literacy Student ChecklistDokument3 SeitenGeneral Financial Literacy Student ChecklistKarsten Walker100% (1)

- Consensus Statements and Clinical Recommendations For Implant Loading ProtocolsDokument4 SeitenConsensus Statements and Clinical Recommendations For Implant Loading ProtocolsLarissa RodovalhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cbse Completed 31TO60AND95TO104Dokument33 SeitenCbse Completed 31TO60AND95TO104tt0% (1)

- Memoir Reflection PaperDokument4 SeitenMemoir Reflection Paperapi-301417439Noch keine Bewertungen

- 7 HR Data Sets for People Analytics Under 40 CharactersDokument14 Seiten7 HR Data Sets for People Analytics Under 40 CharactersTaha Ahmed100% (1)

- Understand SWOT Analysis in 40 CharactersDokument6 SeitenUnderstand SWOT Analysis in 40 Characterstapan mistryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4Dokument12 SeitenSptve Techdrwg7 Q1 M4MarivicNovencidoNicolasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safe Spaces Act Narrative ReportDokument2 SeitenSafe Spaces Act Narrative ReportLian CarrieNoch keine Bewertungen

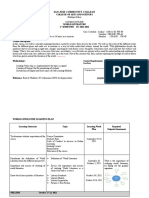

- San Jose Community College: College of Arts and SciencesDokument5 SeitenSan Jose Community College: College of Arts and SciencesSH ENNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0452 s18 Ms 12Dokument14 Seiten0452 s18 Ms 12Seong Hun LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Six Principles of Special EducationDokument36 SeitenSix Principles of Special EducationIsabella Marie GalpoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CISE 301 Numerical MethodsDokument2 SeitenCISE 301 Numerical MethodsMohd Idris Shah IsmailNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dominance and State Power in Modern India - Francine FrankelDokument466 SeitenDominance and State Power in Modern India - Francine FrankelSanthoshi Srilaya RouthuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supply Chain Mit ZagDokument6 SeitenSupply Chain Mit Zagdavidmn19Noch keine Bewertungen

- Future Hopes and Plans - Be Going To - Present Continuous - Will - Be AbleDokument31 SeitenFuture Hopes and Plans - Be Going To - Present Continuous - Will - Be AbleDouglasm o Troncos RiosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment OutlineDokument3 SeitenAssignment OutlineQian Hui LeeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 PilotStudyDokument4 Seiten1 PilotStudyPriyanka SheoranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Undertaking Cum Indemnity BondDokument3 SeitenUndertaking Cum Indemnity BondActs N FactsNoch keine Bewertungen

- (ACV-S06) Week 06 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz (PA) - INGLES IV (36824)Dokument5 Seiten(ACV-S06) Week 06 - Pre-Task - Quiz - Weekly Quiz (PA) - INGLES IV (36824)Gianfranco Riega galarzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Productivity Software ApplicationsDokument2 SeitenProductivity Software ApplicationsAngel MoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Describing Character 1,2 PDFDokument3 SeitenDescribing Character 1,2 PDFalexinEnglishlandNoch keine Bewertungen