Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Jyaanta Mahapatra

Hochgeladen von

ramakntaOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Jyaanta Mahapatra

Hochgeladen von

ramakntaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Abstract on Dawn at Puri by Jayanta Mahapatra Dawn at Puri is an imagist poem (a poem consisting of a number of vivid, sharply etched,

but not necessarily interrelated images). The Panorama of Puri (in rissa! a land of forbidding myth), artistically portrayed with vivid images and symbols, becomes evocative. Puri is the name of a famous town in rissa, which is considered sacred because of the temple dedicated to "ord #agannath, the presiding deity of rissa. This temple is said to date that to $%& '.D. (t is particularly famous for the chariot festival of #agannath) an annual ritual conducted for the glory of this deity and is attended by a large number of pilgrims. *ndless crow noises) a reference to the endless cawing of the crows, a visual as well as an auditory image. ' s+ull on the holy sands, This is a startling imagery created with the -u.taposition of the abstract with the concrete, where the abstract holy and the concrete s+ull are grouped together. (t is believed that the deity of Puri was carved out of a tree trun+ that was washed ashore and this fact is alluded to in his poem "osses. /oping for some +ind of redemption for this wayward world, the spea+er in the poem muses, 0Perhaps the piece of driftwood1 washed up on the beach1 heals the sand and the water2. Puri is regarded as a sacred site and it is the wish of every pious /indu to be cremated there to enable them to attain salvation.

(ts empty country towards hunger, a reference to the poverty to the people of rissa including the sight of the s+ull lying on the sea!beach symboli3es the utter destitution of the people. 4hite!clad widowed women, reference to widows wearing white saris and the phrase that points to their predicament as well as the rigidity of /indu customs and rituals. Past the centers of their lives, having spent the middle years of their lives and passing their prime. Their austere eyes stare li+e those caught in a net, the misery resulting in utter hopelessness is clearly visible on their faces for there is an e.pression of solemnity in the eyes of the widows in which no worldly desire is perceptible and are full of desire li+e the eyes of creatures trapped in a net. Dawns shining strands of faith, ' person having a firm belief in religion never losses hope, so in spite of their circumstances, the only thing that sustains the widows is their religious faith and the hope born of it. The reference to dawn is to be noted. (t refers to a new beginning in nature and thereby, to a new start in man+ind and civili3ation. The tone of 5uiet acceptance, with a latent awareness of suffering, perhaps indicates a very (ndian sensibility. The frail early light, the dim light of the dawn is a reference to the title of the poem which must be noted. "eprous, from leprosy, an infectious disease affecting the s+in and nerves and

causing deformities. ' mass of crouched faces, a large number of timid persons standing in a group, having no confidence in themselves, preferably referring to the lepers and widows who are not allowed to move freely in the town. 'nd suddenly brea+s out of my hide, suddenly emerges from beneath my s+in. ' sullen solitary pyre, ' pile of wood is used for burning a dead body as part of a funeral rite. The sight of this reminds the poet of his mothers last wish to be cremated here as it is the gateway to /eaven or the 6wargadwara which is the name of that part of the long sea! beach where the funeral pyres go on burning. 6ince the temple of "ord #aganath at Puri points to unending rhythm, dying in this place will ta+e one to silence the ultimate desire of a human being which will enable him to attain 7irvana. Twisting uncertainly li+e light on the shifting sands, This is an apt image of the smo+e rising from the funeral pyre where the wind from the sea causes the smo+e to twist uncertainly. This is an e.ample of 8ahapatras transcendal mode and an e.ample of his attempt to trap elusive meanings. The poetic e.ploration of this place turns out to be a search for the self. The view thrills the poet and he becomes an integral part of it, observing a morning scene on the sandy sea!beach in the town of Puri. 9y means of a series of vivid pictures, the atmosphere of dawn has been created. 8ahapatra also underlines the importance of the temple town of Puri and what it means to the /indus in (ndia. Jayanta Mahapatras poem Hunger #ayanta 8ahapatra, along with *3e+iel, :amanu-an and Dom 8oraes, is a ma-or voice of the first wave of modern (ndian *nglish poetry. (n my opinion the wor+s of poets li+e ;olat+ar, 'gha 6hahid 'li stole the luster from the wor+s of these other poets, 8ahapatra held his own. (f he is not as pervasively +nown name as someone li+e *3e+iel, it is due to non!poetic reasons. 8ahapatra is one of the most haunting of the (ndian *nglish poets with a highly demanding poetic style. /e edited a maga3ine called Chandrabhaga for some time. /e started writing late in life, he taught Physics in a <ollege in <uttac+ and began writing after he was =>. 9ut soon he had a substantial body of writing. /is Crossing of the Rivers is a remar+able long poem. 'n abiding motif in his poems is the tangle between tradition and modernity. The picture that emerges in wor+s li+e A Rain of rites is that 8ahapatra tends to position himself on the side of modernity and then rather than challenging or undermining or ironically doubting tradition, he e.amines modernity itself by evo+ing the tradition to throw

posers at his modern location. The modernity of the spea+er in many of 8ahapatras poems is a burden to bear. 9ut, yet his poems do not cast tradition as the preferred resource. (t is the difficulty that this opposition raises that gets foregrounded. ne of his poems that earned a lot of fame is /unger. This poem impressed 9ernard ?oung, the 'merican poet, so much that he 5uoted the whole poem in The Hudson Review. The poem presents two +inds of hunger @ one (physical) leading to the fulfillment of other (se.ual). The theme is 5uite obvious, so let me focus on what ( li+e about this poem. The poem primarily has two structures of images, flesh related and poverty related) hunger emanating from the flesh and that from poverty. 4hat ma+es the poem impressive is the way these images entangle one another, some abstract, all building the irony of the two urges. The vividity of the images build a word portrait of the place, graphically relating the manners of the three characters. The fisherman, the father who pimps his daughter, is careless in his offer of the girl, 0as though his words sanctified the purpose with which he faced himself2. ( thin+ the poet craftily pushes the reader to 5uestion the very ideas of sanctity here. The utter hopelessness in the life of the fisherman and his daughter is such that it words li+e sanctity would be meaningless there. The values have no purchase in so utterly degraded a human plight. The image of wound is prepared to by such images as the bone thrashing in his eyes, mind thumping in the fleshs sling, burning the house body clawing. The actions indicated in these image portray the human effort that is rather desperate, fruitless and hurting. The wound image gathers them all together in a place where the combined force of all these previous images together hits the reader hard and -ump him1her out of complacency. (t must be borne in mind that the tourist searching for se.ual gratification implicitly holds the place of the audience as the reader is a voyeur li+e the tourist. The soot image, a customary suggestion of sin, alerts us to how the blac+ness of the predicament of the father pimping his daughter is a condemnation not of the father but of the society where such a tragedy comes to pass. The soot covers the shac+ of the fisherman, but it is the tourists mind on which the poem sees the soot. Thus, li+e 9la+e who said the presence of a whore in society is a curse of the marriage system, this poem 5uestions the -ustness in society from which sanctity has disappeared.

( have always felt that it is the reader who has to bear the force of irony of this poem. 7otice how the reader in this poem is not allowed to be outside of it. "i+e the tourist in the poem, the reader is an outsider and a sort of voyeur. 6o the shame of the plight of the pimping father falls on the reader @ not on the individual reader.

A profile #ayanta 8ahapatra, born on AA ctober %BA$ in <uttac+, belongs to a lower middle!class family. /ad his early education (from ;indergarhen to <ambridge classes) in *nglish medium at 6tewart school, <uttac+. 'fter his 8asterCs Degree in Physics, he -oined as a teacher in %B=B and served in different Dovernment college of rissa. Dot his superannuation in %B&E when he was in :avenshaw <ollege, <uttac+. #ayanta 8ahapatra began writing poems rather late in comparison with his contemporaries. 9ut this late beginning does not in anyway distort his achievement. /is poems have appeared in most of the reputed -ournals of the world. /e received the prestigious #acob Dlatstein 8emorial 'ward (<hicago) in %BFG. /e is the first (ndian poet in *nglish to have received the <entral 6ahitya '+ademi 'ward(%B&%) for his :elationship . /is other volumes include <lose the 6+y, Ten by Ten, 6vayamvara H ther Poems, ' IatherCs /ours, ' :ain of :ites, 4aiting, The Ialse 6tart H "ife 6ings. /is translations (from riya to *nglish ) bear the stamp of his originality too. /is early poems were born of love, of loveCs selfishness. They celebrate not only passion, the bodyCs spacious business, but consistently evo+e a melancholic atmosphere rent with absences, fears, foreboding and sufferings. 9ut slowly and steadily the poet released himself from this lonesome citadel of love, and learnt involving himself with other men, living or dead with many other succulent chambers of living. Iear of ageing, fear of death, and love for life and memory, love for the golden past an in5uisitiveness to live amid contraries of life, and a complete absorption in and identification with culture and tradition of rissa!all these run simultaneously, as it were, the poet is sincerely trying to uphold the lost dimension of blood and the living. Death is a new beginning for the poet, and life a Ctelegraph +ey tapping away in the dar+C,

<hildhood memories occupy a considerable space in his poetry. /is commitment to and identification with rissa becomes complete when he e.horts the dar+ daughters engraved on the body of the 6un Temple at ;onar+. The richness and sophistication of language, the softness and delicacy of the words chosen, systemati3ed orchestration of authenticated e.periences through the e.act palpability of images, the sincerity of harping on the CfeelC of the e.periences rather than on their CthoughtC, the sweetness of music emerging from a fountain!li+e flow of the verse!form contribute to the greatness and ingenuity of 8ohapatraCs poetry. The Use of mages an! "ymbols in the poetry of Jayant Mahapatra #ayant 8ahapatra made his debut as an (ndian poet writing in *nglish about two decades ago with the publication of his first anthology <lose the 6+y, Ten 9y Ten, and 6econd 6vayamwara and ther Poems, both published in %BF%. The third anthology ' :ain of :ites was published in %BFE. /is many poems have been universally recogni3ed. /e has matured rapidly, and both the 5uality and 5uantity of his poetic output indicate that with the passing of time his poetry would come to be recogni3ed as the best in (ndian *nglish. (n his poetry, we would see that he has maintained a rigid and strict <hristian upbringing within the house, but the outside world was a vast stage of religion rites and rituals, myth and images that the people practised. The pull between these two worlds, therefore, was very obvious, and 8ahapatra e.periences the tension severely as he has e.pressed in his poem, 0Iear of my Duilt, ( 9id you IarewellJ. 4hen the waves come, following one another, the science and 7oise, the banished Princess and the 8agnolia tree is well, a song rises from the honeycomb "atticewor+ of stone to grip these bones where a grey water of blood stretches out to the future.% n the one hand, he had to live in a house that was rigidly <hristian. n the other, the vast landscape of /indu rituals and myths encircled him on all sides. /ow would he feel baffled at the density of images, symbols and the meanings they carried within, be withdrawn and silent because he could not share those structures of meaning KA 8ahapatraCs Poem, CDawn at PuriC <lears ,

*ndless crow noises ' s+ull on the holy sands tilts it empty country towards hunger. 4hite! clad widowed women. Past the centres of their lives are waiting to enter the Dreat Temple.$

'n ample (ndianness is seen at its best in his poems about rissa, where the local and the regional is raised to the level of the universal. J rissa "andscapeJ, J *vening in an rissa villageJ, J The rissa PoemsJ, J Dawn at PuriJ, etc. are riya first, and therefore , (ndian too. ;.'. Pani+ar writes that an e.amination of the recurring images in 8ahapatraCs poems reveals that he is riya to the care. 6ome of 8ahapatraCs images, though they are not many , assume the shape of symbols in his poetry of such recurring images, mention may be made of human failures, nature, a process of disillusionment, and the ma-estic height. 4hile discussing the poem J8ountainJ, we have seen the application of the image of disillusionment, which usually denotes the eternity, facing the process of growth and decay. The fre5uently used image of 7ature in 8ahapatraCs poetry denotes the J 6ub-ective responseJ as distinct from the image of the universal ethos. 8ahapatra offers fresh images of mountain, city, sun and factory in his verse. (n his JThe 8ountainJ, he writes thus , (n the dar+ness of evening silence and pressure only, 8ultiplying, adding, subtracting, (n the abyssal heart.= The city occupies, a central place in 8ahapatraCs poetry. "i+e the image of dar+ness, the image of city is lin+ed with corruption and industriali3ation in modern human life (especially as found in metropolitan cities). The city image is predominant in poem li+e J6now in (owa <ityJ. The following lines of J6now in (owa <ityJ are worth citing in this conte.t ,

/ere the anguish of the old is hidden under the gentle slopes of bearded corn fields. 9ut you can hear it in the footsteps.G 8ahapatra occupies a prominent place in contemporary (ndian *nglish poetry . 'rtistically too, he is a highly talented poet who +nows well how to handle his poetic tool. /is use of images and symbols in poetry spea+s volumes of his trained mind and disciplined art. The images he uses ac5uire the symbolic overtones. 8ahapatraCs enchanting e.pression of 5uite meditativeness, slightly tinged with sorrow and nostalgia the ubi5uitous religious and cultural ambience of rissa bestows a distinctive 5uality upon his verse. /e has spread the fragrance of his poetic leaves abroad that spans the entire globe , (owa <ity, 'delaide, 6ewanee, /awaii, 6ydney, <anberra, To+yo. The woman is yet another image in 8ahapatraCs poetry. 's a symbol, she is usually identified with the Cdiscarded thingsC. 6he is often portrayed as a se.ually oppressed by the so called patriarchal system and poverty. The image of the woman has been vividly presented here in the poem, JThe whorehouse in a <alcutta 6treetJ, he writes thus , Dream <hildren, dar+, superflows) ?ou miss them in the houseCs dar+ spaces, how canCt youK *ven the woman donCt wear them @ "i+e -ewels or precious stones at the throat) the faint feeling deep at a womanCs centre that brings bac+ the discarded things, the little turning of blood at the far edge of the rainbowE /ere simile and metaphore are beautifully yo+ed together. The dream children are depicted as a matter of destroying the emotion of human +indness. The same +ind of images have been drawn in *3e+ielCs poetry in CThe :ailway <ler+C . The tension and the pain of being out of tunes is apparent in the poems li+e J "ostJ, J The 8ountainJ and we would feel very fragmentary 5uality of the images they are discreet entities that e.plore the reality of the world. (n CDawn at PuriC, 8ahapatra depicts with vivid images and symbols of the temple town of Puri with its C endless crow noises) Ca s+ull lying on holy sandsC, he writes thus ,

't Puri, the crows The one wide street lolls out li+e a giant tongue Iive faceless lepers move aside as a Priest passed by . F 8ahapatra e.presses manCs loneliness, his search for roots and identity through images and symbols. C 6hattered faithC, Cmoments of se.ual desireC, Cthe pregnancy of silenceC, dreams and imaginations are articulated with images and symbols. (n C6anctuaryC, 8ahapatra suggests the images of s+y, shape, home and absence, thus he e.presses , now ( close the s+y with a s5uare ten by ten the roof essential hides the apocalyptic ideal the space sings where ( live at home, to hyperbola to s+y! tasted love for the blessing of absence is its essence.& To conclude, 8ahapatra is a s+illed and conscious craftsman who churns out his images and symbols thoughtfully. (n such poems he is an riyan poet first, but he is (ndian too, because by a careful selection of images and symbols, the local becomes symbolic of (ndia as a whole. :. Parthasarathy observes , J The economy of phrasing and starling images recall the subhasitas (literally, that which is well said) of classical 6ans+rit.J B C *vents the e.ile, C the moon momentsC, C total solar eclipseC are conspicuous for the use of imagery, which is realistic suggestive and symbolic. The poem Dawn at Puri The poem 0Dawn at Puri2 narrates by describing the riyan landscape, especially the holy city of Puri . 9efore ( begin to discuss the poem ,let me tell you that 8ahapatra is deeply rooted in (ndian culture and ethos with which he is emotionally attached as a poet . Though the language of e.pression is *nglish his sensibility is riya. ( have repeated this point because in order to appreciate the prescribed poem it is important to understand his sensitive attitude to the native socio cultural practices . /ere in the poem under discussion,

Puri is the living protagonist for him .Puri is not only a setting but also a protagonist because he presents a graphic description of Puri as a central character ./ere Puri is personified. 't Puri, we find a stretch of beach called 6wargadwara or Dateway to heaven where the dead are cremated . 8any pious /indus and widows feel that it is possible to attain salvation by dying at Puri . 8ahapatra states, 0/er last wish to be cremated here1 twisting uncertainly li+e light1 on the shifting sands.2 Puri is not only famous as a place for the four dhams or sacred cities but also for the math or the monastery set up by 6han+aracharya . "ord #agganath is the main deity in Puri who is in the form of "ord Lishnu . The way 8ahapatra delineates the events and incidents in the poem shows us that he disapproves of what is going on under the cover of tradition and practices. ?ou will notice how life 0lies li+e a mass of crouched faces without names2 and you also can see how people are trapped by faith as e.pressed in the e.pression 0caught in a net 0. The shells on the sand are 0ruined2 the word , 0 leprous2 is suggestive of decadence and infirmity . The poem evo+es loss of identity , anonymity, death , disease and decadence . 's ( have mentioned above, most of the /indus wished to be cremated in the land of "ord Lishnu. The spea+ers mother also had such a last wish, the wish to be cremated in Puri. This is fulfilled by the effort of her son in the bla3ing funeral pyre which is seen as 0sullen2 and 0solitary2 .The poem winds up on an uncertain note li+e the corpse of his dead mother . Dont you thin+ the title evo+es many interpretations K The title of the poem is very suggestive as it does not tal+ about only one particular dawn which might have been particularly unpleasant because ones mother is not cremated everyday . 9ut personally one could feel that this dawn could be made more special .The poet is suggesting that all dawns at Puri are more or less similar with dead mothers being cremated everyday and crows cawing along with s+ulls and hunger indicating poverty! ridden (ndia which shows absolute 0(ndianness0. The poem is about feelings and compassion for the people who suffer . "et me tell you that the poem is really a scathing attac+ on tradition and traditional practices which are mostly ruthless and biased . The poet bears no sympathy for rituals and hollow traditions. 4hat we notice in the poem is emptiness of tradition , the indifference of society and fossili3ed /indu culture. Abstract on "ummer by Jayanta Mahapatra

8ahapatra sees the world with detachment, comprehends the reality that he encounters in the world, and portrays it ob-ectively. The force of this poem lies in its peculiar evocation of images and ordering of e.perience, not in what can be abstracted from it. This poem offers a few pictures which are by no means interconnected, and it reads li+e a riddle. 9ut the pictures are vivid and realistic. 7ot yet) the words focus on an event that will come after the current time. ne needs to understand the poem to find out what is not yet to ta+e place, or to happen, or to be done. The lines convey the impossibility of unraveling the mystery of life. 8ahapatras poetry is a continual effort to understand the nature of the reality he inhabits and embodies. The cold ash of a deserted fire) the first picture is an evocative image of the dying ashes of a fire lit under a mango tree, which has subse5uently gone out. Things, images and the world of phenomena are means by which the un+nown may be +nown. 4ho needs the futureK) a one!line rhetorical and ambiguous 5uestion which is not directly answered, where 8ahapatra writes a poetry of 5uestioning. <rows of rivalries are 5uietly nestling) an idea e.pressed in metaphorical language where the crows are not real but reference is made to the domestic rivalries and -ealousies which e.ist in the mothers head. <rows are symbols of evil, guilt and destruction in his poems. The home will never be hers) the girls home belong to her brothers, after her marriage she would go to her husbands home. 8ahapatra ironically refers to the way the (ndian woman is not given a space or voice of her own as an individual in her own right. ' living green mango drops softly to the earth) a green mango is unripe and its falling to the ground is premature. (n the same way, the e.pectations in this young girls heart to be and become an individual without limitation or constriction have come to an end, probably referring to the early marriages in the (ndian villages. 'n important aspect of his diction is the use of humani3ing epithets for the non!human and inanimate.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Abstract On "Dawn at Puri" by Jayanta MahapatraDokument10 SeitenAbstract On "Dawn at Puri" by Jayanta MahapatraVada DemidovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Notes: English Literature, GCE OL Examination, Sri Lanka 2017 - R.SubasingheDokument49 SeitenNotes: English Literature, GCE OL Examination, Sri Lanka 2017 - R.SubasingheRathnapala Subasinghe91% (234)

- Elements of Indian Ness in Jayanta MahapatraDokument9 SeitenElements of Indian Ness in Jayanta MahapatraBhawesh Kumar Jha50% (2)

- Music of TWLDokument13 SeitenMusic of TWLnicomaga2000486Noch keine Bewertungen

- John Keats Summary & Analysis203 - 220818 - 105324Dokument84 SeitenJohn Keats Summary & Analysis203 - 220818 - 105324Adman AlifAdmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Cyclical in W.B. Yeats's Poetry.Dokument13 SeitenThe Cyclical in W.B. Yeats's Poetry.Ane González Ruiz de LarramendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Romantic Era Poem AnalysisDokument4 SeitenRomantic Era Poem Analysiss07030125Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sarvajna Bio GokakDokument12 SeitenSarvajna Bio GokaktelugutalliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dawn at PuriDokument2 SeitenDawn at PuriSrestha DuttaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IwanderedlonelyasacloudDokument21 SeitenIwanderedlonelyasacloudYanHongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern AbbeyDokument4 SeitenLines Composed A Few Miles Above Tintern Abbeysobia faryadali100% (1)

- William Wordsworth - I Wandered Lonely As A CloudDokument3 SeitenWilliam Wordsworth - I Wandered Lonely As A CloudCarmen SimionovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Alice Corbin Henderson - A Note On Primitive Poetry PDFDokument7 SeitenAlice Corbin Henderson - A Note On Primitive Poetry PDFVictor H AzevedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 11th Class Explanation.Dokument9 Seiten11th Class Explanation.moizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ode To An Gracian Urn John Keats-1Dokument5 SeitenOde To An Gracian Urn John Keats-1usama aliNoch keine Bewertungen

- English LiteratureDokument6 SeitenEnglish LiteratureArpit SamuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comedy. in The Three-Line Terza Rima Stanza, The First and Third Lines Rhyme, and The Middle Line DoesDokument3 SeitenComedy. in The Three-Line Terza Rima Stanza, The First and Third Lines Rhyme, and The Middle Line DoesMichela MaroniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rhapsodomancy X Stanzas For A Sierra MorningDokument6 SeitenRhapsodomancy X Stanzas For A Sierra MorningArsalan SheikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- PoemDokument7 SeitenPoemShamari BrownNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bege 101Dokument0 SeitenBege 101Shashi Bhushan SonbhadraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Our Casurina TreeDokument12 SeitenOur Casurina TreeAshique ElahiNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Wandered Lonely As A Cloud Analysis, Summary, Theme, Rhyme Scheme, Literary Devices - All About English LiteratureDokument13 SeitenI Wandered Lonely As A Cloud Analysis, Summary, Theme, Rhyme Scheme, Literary Devices - All About English LiteratureChandanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Margaret Atwood Notes Towards A PoemDokument5 SeitenMargaret Atwood Notes Towards A Poemsanamachas100% (2)

- II Semester NotesDokument11 SeitenII Semester Noteskingsley_psbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shesher Kobita ExcerptsDokument19 SeitenShesher Kobita ExcerptsPonnu ChamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Opinion On Nuit de SineDokument4 SeitenOpinion On Nuit de SineAgboola JosephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Read DevkotaDokument29 SeitenRead DevkotaMahesh ThapaliyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Aa 159555 CfefDokument7 Seiten5 Aa 159555 CfefDaffodilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dawn at Ouri - Critical AppreciationDokument8 SeitenDawn at Ouri - Critical AppreciationDaffodilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negro Speaks of RiversDokument11 SeitenNegro Speaks of RiverssanamachasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ode On A Grecian Urn by John KeatsDokument9 SeitenOde On A Grecian Urn by John Keatsاحمد خاشع ناجي عبد اللطيفNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resúmenes y Análisis Literary TextsDokument66 SeitenResúmenes y Análisis Literary TextsVero GuigeNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Wandered Lonely As A CloudDokument19 SeitenI Wandered Lonely As A CloudPutu Wulan Sari AnggraeniNoch keine Bewertungen

- شعر حسب د.باسلDokument15 Seitenشعر حسب د.باسلعبدالرحمن كريمNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rain Is One of The Most Beautiful Phenomena of NatureDokument4 SeitenRain Is One of The Most Beautiful Phenomena of NatureAkram SaqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical AnalysisDokument4 SeitenCritical AnalysisshahzadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poems by Nilamani PhookanDokument9 SeitenPoems by Nilamani PhookanMeitei NupineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sonnet Composed Upon Westminster BridgeDokument6 SeitenSonnet Composed Upon Westminster BridgeFayeed Ali Rassul0% (1)

- English Class 12 Poem SummaryDokument8 SeitenEnglish Class 12 Poem SummarySubhadeep Chandra100% (2)

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDokument5 SeitenOde On A Grecian UrnAslı As100% (1)

- Daffodils SummaryDokument9 SeitenDaffodils SummaryNivetha Chandrasekar100% (1)

- Tintern AbbeyDokument4 SeitenTintern AbbeyGirlhappy Romy100% (2)

- A Vision PDFDokument13 SeitenA Vision PDFAbhishekNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Wandered Lonely As A CloudDokument17 SeitenI Wandered Lonely As A CloudYosh QuinNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Pot To Dam: Media Ecology in LiteratureDokument7 SeitenFrom Pot To Dam: Media Ecology in LiteratureSivarajan RajangamNoch keine Bewertungen

- I Wandered Lonely As A Cloud By: William WordsworthDokument6 SeitenI Wandered Lonely As A Cloud By: William WordsworthNympha’s DiaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Poetry of Ajit BaruaDokument22 SeitenThe Poetry of Ajit BaruaBISTIRNA BARUANoch keine Bewertungen

- Personae: Aims and ObjectivesDokument7 SeitenPersonae: Aims and ObjectivesKasavaraju DharaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Kannada Tagore Shivarama Karanth: Ramachandra GuhaDokument9 SeitenThe Kannada Tagore Shivarama Karanth: Ramachandra Guhaபூ.கொ. சரவணன்Noch keine Bewertungen

- My Reminisces: "We cross infinity with every step; we meet eternity in every second."Von EverandMy Reminisces: "We cross infinity with every step; we meet eternity in every second."Noch keine Bewertungen

- A K Ramanujan PoetryDokument8 SeitenA K Ramanujan PoetrySourav KapriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Photograph Study Notes Cbse Class 11Dokument12 SeitenPhotograph Study Notes Cbse Class 11imettygirlNoch keine Bewertungen

- AshberyDokument4 SeitenAshberyJahanzaib DildarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Daffodils Q & ADokument18 SeitenDaffodils Q & ADipanjan Pal100% (2)

- GPLF Monthly Transaction Report Format For CEFDokument1 SeiteGPLF Monthly Transaction Report Format For CEFramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TB Þeerþeeròepeehele Es VeceëDokument2 SeitenTB Þeerþeeròepeehele Es VeceëramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chhabila Sir RtiDokument3 SeitenChhabila Sir RtiramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Revision Case No.-84/10 Dt.17-12-2019: in The Court of Additional District Judge - Ii, CuttackDokument4 SeitenCriminal Revision Case No.-84/10 Dt.17-12-2019: in The Court of Additional District Judge - Ii, CuttackramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- To The Hon'ble Sj. Pinaki Mishra Member of Parliament, Puri Sub: Reference For Restoration of Pre-Paid Auto Services at Puri Municipality Bus Stand Out Gate, Puri. SirDokument1 SeiteTo The Hon'ble Sj. Pinaki Mishra Member of Parliament, Puri Sub: Reference For Restoration of Pre-Paid Auto Services at Puri Municipality Bus Stand Out Gate, Puri. SirramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fakir Mohan Senapati: Renaissance in Odia Literature: Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669Dokument3 SeitenFakir Mohan Senapati: Renaissance in Odia Literature: Odisha Review ISSN 0970-8669ramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Life and Times of Fakirmohan Senapati: Orissa Review February - March - 2008Dokument6 SeitenLife and Times of Fakirmohan Senapati: Orissa Review February - March - 2008ramaknta100% (1)

- Distance Certificate: SL No. Name of Procurement Center OSWC Sakhigopal Distance OSWC Jagatpur DistanceDokument1 SeiteDistance Certificate: SL No. Name of Procurement Center OSWC Sakhigopal Distance OSWC Jagatpur DistanceramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Received RsDokument2 SeitenReceived RsramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NeoDokument21 SeitenNeoramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impact of Foreign Direct Investment On Life Insurance Sector in IndiaDokument3 SeitenImpact of Foreign Direct Investment On Life Insurance Sector in IndiaramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Project DocumentatiionDokument21 SeitenProject DocumentatiionramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- To The Block Education Officer, Puri Sub:-Grant of Family Pension To The Dependant Daughter. Respected Sir/MadamDokument2 SeitenTo The Block Education Officer, Puri Sub:-Grant of Family Pension To The Dependant Daughter. Respected Sir/MadamramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume: Name Father's Name Present AddressDokument2 SeitenResume: Name Father's Name Present AddressramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BSE OdishaDokument8 SeitenBSE OdisharamakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Current Gain × Resistance Gain: Output Section Resistance Inout Section ResistanceDokument1 SeiteCurrent Gain × Resistance Gain: Output Section Resistance Inout Section ResistanceramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Do You NeedDokument1 SeiteWhat Do You NeedramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ToDokument2 SeitenToramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Form 11 RevisedDokument1 SeiteForm 11 RevisedramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

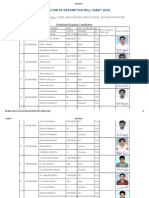

- I Card TSC 2016Dokument12 SeitenI Card TSC 2016ramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculam Vitae: ObjectiveDokument3 SeitenCurriculam Vitae: ObjectiveramakntaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Socialization - Become Human and HumaneDokument24 SeitenSocialization - Become Human and HumaneBogdanC-tinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bibliography of PhilemonDokument9 SeitenBibliography of PhilemonRobert Carlos CastilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pillow Book Chapter 18 Part 1Dokument9 SeitenThe Pillow Book Chapter 18 Part 1FrostNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family HymnsDokument24 SeitenFamily Hymns:: fieldwork ::Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yoga For Beginners Simple Yoga Poses To Calm Your Mind and Strengthen Your BodyDokument219 SeitenYoga For Beginners Simple Yoga Poses To Calm Your Mind and Strengthen Your BodyRàj Säñdhu100% (11)

- Nymphs of The ValleyDokument7 SeitenNymphs of The ValleyNIcole AranteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greek & Roman Mythology (Gods & Goddesses)Dokument2 SeitenGreek & Roman Mythology (Gods & Goddesses)Christopher MacabantingNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Beautiful Is The Morning: Birthday SongsDokument4 SeitenHow Beautiful Is The Morning: Birthday SongsfendyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basu Colonial Educational Policies Comparative ApproachDokument12 SeitenBasu Colonial Educational Policies Comparative ApproachKrati SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- MBC Bulletin - November 3 2013 PDFDokument8 SeitenMBC Bulletin - November 3 2013 PDFMBCArlingtonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diocesan Youth Days 9: Objective(s) For The DayDokument4 SeitenDiocesan Youth Days 9: Objective(s) For The DayRaffy RoncalesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gil Anidjar PDFDokument26 SeitenGil Anidjar PDFblah blah 56743Noch keine Bewertungen

- Alpha DruidDokument35 SeitenAlpha DruidIlina Selene YoungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samadhi TemplesDokument60 SeitenSamadhi Templesthryee100% (1)

- The Pitfalls of A Leader by Henry Blackaby: Open As PDFDokument9 SeitenThe Pitfalls of A Leader by Henry Blackaby: Open As PDFElijahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mesopotamia and Egypt HandoutDokument3 SeitenMesopotamia and Egypt HandoutEcoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LW Love Forgiveness & Magic (Ursilius & Hana) 090101Dokument16 SeitenLW Love Forgiveness & Magic (Ursilius & Hana) 090101Claudia GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- L010 - Madinah Arabic Language CourseDokument25 SeitenL010 - Madinah Arabic Language CourseAl HudaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women's Movement in India PDFDokument15 SeitenWomen's Movement in India PDFSangram007100% (1)

- Jesus Is - : Student EditionDokument15 SeitenJesus Is - : Student EditionThomasNelson100% (1)

- G11 TG3 Group 7Dokument51 SeitenG11 TG3 Group 7Vivian AranjuezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ang Aking Scrapbook Sa Araling PanlipunanDokument14 SeitenAng Aking Scrapbook Sa Araling PanlipunanCharing ZairieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bach Flower Remedy LeafletDokument12 SeitenBach Flower Remedy LeafletJanaki Kothari100% (1)

- Art and ArchitectureDokument3 SeitenArt and Architectureapi-291662375Noch keine Bewertungen

- Censorship in Saudi ArabiaDokument97 SeitenCensorship in Saudi ArabiainciloshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Presbyterian Kohhran Pathian Biak KalphungDokument5 SeitenPresbyterian Kohhran Pathian Biak KalphungHmangaiha Hahn HmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Milarepas Ten Paramitas SongDokument10 SeitenMilarepas Ten Paramitas SongpatxiNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Joy That I Have, The World Didn't Give MeDokument3 SeitenThis Joy That I Have, The World Didn't Give MeJeff BarteNoch keine Bewertungen

- ST. AugustineDokument3 SeitenST. AugustineJohn Paul DungoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islam Dan Modernisme Di Indonesia: Kontribusi Pemikiran Mohamad Rasjidi (1915-2001) Mohammad Zakki AzaniDokument36 SeitenIslam Dan Modernisme Di Indonesia: Kontribusi Pemikiran Mohamad Rasjidi (1915-2001) Mohammad Zakki Azanicep dudNoch keine Bewertungen