Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cincinnati Children's Sleep Study

Hochgeladen von

SundanceSolutionsCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cincinnati Children's Sleep Study

Hochgeladen von

SundanceSolutionsCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Sleep Organization in Premature Infants: Implications for Developmentally Supportive Caregiving and Collaboration in the NICU Marty O.

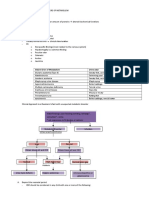

Visscher, PhD1, Linda Lacina, RN1, Tammy Casper, DNP1, Melodie Dixon, RRT1,2, Joann Harmeyer, RRT1,2, Beth Haberman, MD1, Jeffrey Alberts, PhD3, Narong Simakajornboon, MD1,2, 1Newborn Intensive Care Unit, 2Division of Pulmonary and Sleep Medicine, Cincinnati Childrens Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, 3 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN Background and Purpose: For infants born too soon, the environment changes dramatically from the protective, supportive womb to a setting that must save the infants life and provide for brain growth and development. The neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) can create a stressful milieu for the premature infant due to noise, light, handling, and painful procedures that can bring about disruption of infant sleep-wake cycles and self-regulatory behaviors. Sleep deprived young animals experience loss of brain plasticity, reduced learning and behavioral deficits. Cycling from active to deep sleep is required for neurosensory processing, learning, and memory formation. Differential organization of sleep states in premature infants predicts later developmental disabilities. Therapeutic positioning contains the preterm infant and prevents the consequences of uneven motor development. After we introduced a conformational positioner for routine use, our infants seemed to calm more easily, be more physiologically stable and sleep better. We hypothesized that the positioner would facilitate sleep organization and, thereby, help the infant regulate attention, state and motor responses. The objective was to determine the sleep organization, sleep state and behavior during use of a conformational positioner (CP) versus the standard crib mattress (SP) among premature infants with feeding difficulties. Methods: A randomized controlled trial using a within subject paired comparison design was conducted among 25 infants of 31.5 0.6 weeks gestational age (mean standard error) and 38.4 0.6 weeks adjusted age at the time of the study. They were not on mechanical ventilation, had not taken sedatives for 24 hours, and did not have arthrogryposis, osteogenesis or conditions that limited movement. All infants were then receiving at least some feeds by mouth. Infants used both CP and SP during an overnight polysomnography (electroencephalogram, EEG), conducted with the standard infant montage and simultaneous monitoring of the following parameters: left/right electrooculograms (ROC/A1, LOC/A2), 6 channels electroencephalogram (F3M2, F4M1, C3M2, C4M1, O1M2, O2M1), chin/ intercostal EMG, EKG, oxygen saturation, pulse amplitude wave, and video monitoring). The infants were on each intervention for one half of the 10.5 hour study. All studies were scored by two qualified scorers (a registered polysomnographic technologist and a board certified sleep specialist) with special emphasis on sleep parameters and arousals. Each scorer was blinded to the study treatment. Additionally, infant sleep states and behaviors were evaluated by two experienced developmental care nurses during two 30-minute periods, one on CP and one on SP. They assessed sleep state, autonomic, motor, organization, attention, and self-regulation behaviors as present or absent using the naturalistic observation of newborn behavior (NONB) method during 2 minute intervals. The frequencies of stress 1

and regulatory behaviors were determined by summing the occurrences. The sleep data acquired by behavior observation and by EEG were compared. The effects of CP versus SP on sleep outcomes, sleep state and behavior were evaluated using univariate general linear models procedures with patient characteristics as covariates and correlation methods. Results: Overall When infants were on the conformational positioner, the mean sleep efficiency was 61.3%, significantly higher than the 54.3% efficiency on the mattress (p = 0.05). By behavioral state observations, infants on CP spent less time in awake states than on SP over 30 minutes, with values of 12% and 28%, respectively (p < 0.05). The frequency of self-regulatory behaviors was higher on CP (16) versus SP (11, p < 0.05). The percent of time in deep sleep or quiet sleep was positively correlated with EEG sleep efficiency (r = 0.78, p < 0.05) and negatively correlated with the number of state shifts per hour (r = -0.65, p < 0.05). Sleep efficiency as measured by polysomnography was higher and time awake was lower on CP versus SP (p < 0.05) during the 30-minute observation periods. Arousals by EEG were significantly related to the stress behaviors (p < 0.05) but not to regulatory behaviors. Arousals and stress behaviors appear to occur simultaneously or with stress behaviors lagging arousals. Surgery Subgroup Analysis The potential impact of prior surgery was examined by comparing the sleep outcomes for infant subgroups by surgery (with and without) while controlling for intervention effects. Sleep efficiency was higher on CP than SP for subjects who had surgery (n = 9) compared to the non-surgery group. The surgical subjects had lower sleep efficiency (51.3% versus 61.3%), lower active sleep (38.6% versus 46.0%) and a higher arousal index (30 per hour versus 23) compared to the no-surgery group (p < 0.05). During the 30-minute observation, surgical subjects spent more time in awake states (31% versus 15%) and displayed a higher number of behavior state changes (7.1 versus 4.2) than the non-surgical infants (p < 0.05). The groups did not differ in time in asleep states (deep, quiet) or in the number of stress behaviors. Similarly, sleep efficiency was higher on CP than SP for infants with necrotizing enterocholitis or gastroschisis (n = 10) compared to infants with general feeding difficulty (n = 15) (p < 0.05). Conclusions and Impact: Premature infants are vulnerable to internal and external stressors after birth. Improvements to the NICU environment to mitigate stress are ongoing. The use of a conformational positioner to provide customized containment resulted in higher sleep efficiency relative to the standard mattress among 25 premature infants with feeding difficulties. Infants who had surgery or specific gastrointestinal diagnoses appeared to have poorer sleep quality than infants without these conditions. Infants on CP spent more time in sleep states and exhibited self-regulatory behaviors more frequently compared to the mattress for the 30-minute observation period. Measures of premature infant sleep by behavioral observation were positively correlated to sleep efficiency and negatively to the number of state shifts per hour. Infants requiring surgery or with 2

gastrointestinal diagnoses may be more susceptible to environmental stress. Implementation of sleep-augmenting strategies, including the use of CP, is an important area of focus. The findings support the need for larger trials earlier in the NICU stay (closer to birth) and over time to evaluate the impact of conformation positioning on sleep ontogeny in premature infants during hospitalization and on developmental milestones, e.g., time to full feeds, length of stay, and self-regulatory behavior. Our results extend previous reports that sleep states by behavioral observation correlate with EEG-based sleep results and can be used to evaluate interventions for improved sleep. The power of observation becomes critical for improving sleep quality. It is essential for every caregiver to pay close attention to the preterm infant's interactions, as behavior is indicative of brain function. Developmentally supportive care aims to facilitate neurodevelopment. It is essential for nursing and physician leadership to champion the implementation of developmental care and to measure the outcomes in practice.

Learner Objectives 1. Describe the factors that influence premature infant sleep in the NICU, the effects on neurodevelopment and the long term implications. 2. Discuss the use of developmentally supportive care strategies and the method of behavioral observations to promote sleep in premature infants in the NICU. Bibliography1-5 1. 2. 3. Graven S. Sleep and brain development. Clin Perinatol. 2006;33(3):693-706, vii. Maquet P, Smith, C., Stickgold, R. Sleep and brain plasticity. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. Whitney MP, Thoman EB. Early sleep patterns of premature infants are differentially related to later developmental disabilities. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 1993;14(2):71-80. Ednick M, Cohen AP, McPhail GL, Beebe D, Simakajornboon N, Amin RS. A review of the effects of sleep during the first year of life on cognitive, psychomotor, and temperament development. Sleep. 2009;32(11):1449-1458. Ludington-Hoe SM, Johnson MW, Morgan K, Lewis T, Gutman J, Wilson PD, et al. Neurophysiologic assessment of neonatal sleep organization: preliminary results of a randomized, controlled trial of skin contact with preterm infants. Pediatrics. 2006;117(5):e909-923.

4.

5.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- GORRES - Activity #4Dokument1 SeiteGORRES - Activity #4Carol GorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Study of Amount of Casein in Different Samples of MilkDokument9 SeitenStudy of Amount of Casein in Different Samples of MilkPratyush Sharma80% (79)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Chemistry Project On Study of Rate of Fermentation of JuicesDokument6 SeitenChemistry Project On Study of Rate of Fermentation of Juicesyash dongreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Metamorphosis Rock, Paper, Scissors: Teacher Lesson PlanDokument6 SeitenMetamorphosis Rock, Paper, Scissors: Teacher Lesson Planriefta89Noch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- 5 Enzymes: 0610 BiologyDokument9 Seiten5 Enzymes: 0610 BiologyAbdul HadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Ameloblast CycleDokument75 SeitenAmeloblast CycleAME DENTAL COLLEGE RAICHUR, KARNATAKANoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- S4 - Ojo FisiologiaDokument6 SeitenS4 - Ojo FisiologiaLUIS FERNANDO MEZA GONZALESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Donat - Leaching PDFDokument18 SeitenDonat - Leaching PDFMilenko Matulic RíosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Summary Nelsons Chapter 84Dokument2 SeitenSummary Nelsons Chapter 84Michael John Yap Casipe100% (1)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Douluo Dalu V20 - Slaughter CityDokument102 SeitenDouluo Dalu V20 - Slaughter Cityenrico susantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBSE Class 10 Life Processes MCQ Practice SolutionsDokument14 SeitenCBSE Class 10 Life Processes MCQ Practice SolutionsRAJESH BNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Check List: Serra Do Urubu, A Biodiversity Hot-Spot For Angiosperms in The Northern Atlantic Forest (Pernambuco, Brazil)Dokument25 SeitenCheck List: Serra Do Urubu, A Biodiversity Hot-Spot For Angiosperms in The Northern Atlantic Forest (Pernambuco, Brazil)SôniaRodaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Cover Letter Samples For Your Scientific ManuscriptDokument11 Seiten5 Cover Letter Samples For Your Scientific ManuscriptAlejandra J. Troncoso100% (2)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Nanotechnology - Volume 5 - NanomedicineDokument407 SeitenNanotechnology - Volume 5 - NanomedicineArrianna WillisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Kuliah 12 Dan 13 Island BiogeographyDokument94 SeitenKuliah 12 Dan 13 Island BiogeographylagenkemarauNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Total Coliform Multiple Tube Fermentation Technique - EPADokument18 SeitenTotal Coliform Multiple Tube Fermentation Technique - EPARaihana NabilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Roots Stem and LeavesDokument1 SeiteRoots Stem and Leavesyvone iris salcedoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 242c33f8 A8d5 9ab6 F6ac A366ee824b75 Wecan DancinghandDokument160 Seiten242c33f8 A8d5 9ab6 F6ac A366ee824b75 Wecan DancinghandTourya Morchid100% (1)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Dihybrid ProblemsDokument7 SeitenDihybrid Problemsbrenden chapmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Science 10 Quarter 3Dokument16 SeitenScience 10 Quarter 3Ela Mae Gumban GuanNoch keine Bewertungen

- " The Nervous System, Part 1: Crash Course A&P #8 ":: Longest Shortest CAN CannotDokument7 Seiten" The Nervous System, Part 1: Crash Course A&P #8 ":: Longest Shortest CAN CannotNargess OsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- M. Beals, L. Gross, and S. Harrell (2000) - Diversity IndicesDokument8 SeitenM. Beals, L. Gross, and S. Harrell (2000) - Diversity Indiceslbayating100% (1)

- Biochemistry Review Slides 26 May 2011 PPTX Read OnlyDokument28 SeitenBiochemistry Review Slides 26 May 2011 PPTX Read OnlyMark MaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Dr. Ramakrishna Bag: Civil Engineering Dept NIT RourkelaDokument17 SeitenDr. Ramakrishna Bag: Civil Engineering Dept NIT RourkelaJon JimmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 BM 2008-09Dokument26 Seiten2 BM 2008-09Nagham Bazzi100% (2)

- Embryonic Stem CellsDokument3 SeitenEmbryonic Stem CellsRajNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Annotated Checklist of The Angiospermic Flora of Rajkandi Reserve Forest of Moulvibazar, BangladeshDokument21 SeitenAn Annotated Checklist of The Angiospermic Flora of Rajkandi Reserve Forest of Moulvibazar, BangladeshRashed KaramiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- G9 - Lesson 1 Cardiovascular SystemDokument7 SeitenG9 - Lesson 1 Cardiovascular SystemKhrean Kae SantiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Manonmaniam Sundaranar University Tirunelveli: Scheme of ExaminationsDokument22 SeitenManonmaniam Sundaranar University Tirunelveli: Scheme of ExaminationsSri NavinNoch keine Bewertungen

- M.sc. Botany SyllabusDokument80 SeitenM.sc. Botany SyllabusMuhammad KaleemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)