Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

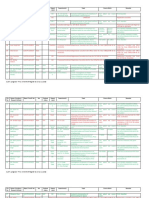

History Handouts For Id Unitt

Hochgeladen von

api-252254205Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

History Handouts For Id Unitt

Hochgeladen von

api-252254205Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Culture of Abundance and Consumerism

The 1950s were a time of expanded consumption of household goods, spurred by a rise in overall prosperity within America.

KEY POINTS

The rise of the white middle class spread income around more evenly, giving the economy many new consumers. White, middle class Americans began moving from cities to the suburbs. During the postwar era, discretionary income and luxury spending rose by over fifty percent. For the first time, Americans were able to own automobiles and homes in large numbers. The ubiquity of the forty-hour work week and increased income gave rise to many leisure activities. New household products such as the washing machine, lawn mower, and vacuum cleaner created the role of housewife for middle class women.

TERMS

Discretionary Income

Money remaining after all bills are paid off. It is income after subtracting taxes and normal expenses (such as rent or mortgage, utilities, insurance, medical, transportation, property maintenance, child support, inflation, food and sundries, etc. ) to maintain a certain standard of living.

conspicuous consumption

A public display of acquisition of possessions with the intention of gaining social prestige; excessive consumerism in order to flaunt one's purchasing power. In the 20th century, the significant improvement of the standard of living of a society, and the consequent emergence of the middle class, broadly applied the term "conspicuous consumption" to the men, women, and households who possessed the discretionary income that allowed them to practice the patterns of economic consumptionof goods and serviceswhich were motivated by the desire for

prestige and the public display of social status, rather than by the intrinsic, practical utility of the goods and the services proper. In the 1920s, economists such as Paul Nystrom proposed that changes in the style of life, made feasible by the economics of the industrial age, had induced to the mass of society a "philosophy of futility" that would increase the consumption of goods and services as a social fashion an activity done for its own sake. The immediate years unfolding after World War II were generally ones of stability and prosperity for Americans. The nation reconverted its war machine back into aconsumer culture almost overnight and found jobs for 12 million returning veterans. Increasing numbers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more cars and home comforts like vacuum cleaners, washing machineswhich were all made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era. The American economy grew dramatically in the post-war period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. During this period of prosperity, many incomes doubled in a generation, described by economist Frank Levy as "upward mobility on a rocket ship. " The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered to be reserved for the wealthy. By the end of the Fifties, 87% of all American families owned at least one T.V., 75% owned cars, and 60% owned their homes.By 1960, blue-collar workers had become the biggest buyers of many luxury goods and services. In addition, by the early seventies, post-World War II American consumers enjoyed higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country. Between 1946 and 1960, the United States witnessed a significant expansion in the consumption of goods and services. GNP rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, cumulative gains which were reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year 52% of consumer units in the metropolitan areas owned their own homes. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Car ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960. The period from 1946 to 1960 also witnessed a significant increase in the paid leisure time of working people. The forty-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960. Paid vacations also became to be enjoyed by the vast majorityof workers.

Industries catering to leisure activities blossomed as a result of most Americans enjoying significant paid leisure time by 1960. Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries while a higher proportion of young people were graduating from high schools and universities than elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. At the center of middle-class culture in the 1950s was a growing demand for consumer goods, a result of the postwar prosperity, the increase in variety and availability of consumer products, and television advertising. America generated a steadily growing demand for better automobiles, clothing, appliances, family vacations, and higher education. With Detroit turning out automobiles as fast as possible, city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban life style centered around children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed a third of the nation's population by 1960. The growth of suburbs was not only a result of postwar prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20- and 30-year mortgages, and low down payments, especially for veterans. William Levitt began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large "Levittown" housing development on Long Island. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom. Suburbs provided larger homes for larger families, security from urban living, privacy, and space for consumer goods.

https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/the-politics-and-culture-of-abundance-1943-1960/the-culture-ofabundance/the-culture-of-abundance-and-consumerism/

Mass Marketing, Advertising, and Consumer Culture

By 1900, advances in consumer education and mass production helped advertising to become firmly established as an industry.

KEY POINTS

In 1840, Volney B. Palmer established the roots of the modern day advertising agency in Philadelphia by buying large amounts of space in various newspapers at a discount and then reselling to advertisers at a higher rate. Prior to the Industrial Revolution, members of the working classes worked long hours for low wages and had little time or money left for consumer activities. Frederick Winslow Taylor brought his theory of scientific management to the organization of the assembly line in commodity industries which unleashed incredible productivity and cost savings and ushered in the era of mass consumption.

TERM

Henry Ford

The Founder of Ford Motor Company and pioneer of the assembly-line technique of mass production. His system of Fordismthe mass production of inexpensive consumer goods with high wages for laborersrevolutionized the American economy. Advertising is a form of communication used to encourage or persuade an audience to take some action. Most commonly, the desired result is to drive consumer behavior with respect to a commercial offering, although political and ideological advertising is also common. The purpose of advertising may also be to reassure employees or shareholders that a company is viable or successful.

Advertising History

Egyptians used papyrus to make sales messages and wall posters. Commercial messages and political campaign displays have been found in the ruins of Pompeii and ancient Arabia. Wall or rock painting for commercial advertising is another

manifestation of an ancient advertising form, which today is still present in many parts of Asia, Africa, and South America. As the towns and cities of the Middle Ages began to grow, and the general populace was unable to read and so signs that today would use an image associated with their trade such as a boot for a cobbler or a suit for a tailor. Fruits and vegetables were sold in the city square from the backs of carts and wagons and their proprietors used street callers (town criers) to announce their whereabouts for customers. As education advanced literacy, advertising expanded to include handbills. In the 18th century, advertisements started to appear in weekly newspapers in England. These early print advertisements were used mainly to promote books and newspapers as well as medicines, which were increasingly sought after as disease ravaged Europe. However, false advertising and so-called "quack" advertisements became a problem, which later ushered in the regulation of advertising content.

Industrialization and Economical Growth

As the economy expanded during the 19th century, advertising grew as well. In June 1836, the French newspaper La Presse was the first to include paid advertising in its pages, allowing it to lower its price, extend its readership, and increase profitability. Around 1840, Volney B. Palmer established the roots of the modern day advertising agency in Philadelphia. In 1842, Palmer bought large amounts of space in various newspapers at a discounted rate then resold the space at higher rates to advertisers. The actual ad was still prepared by the company wishing to advertise, making Palmer a space broker. The situation changed in the late 19th century when the advertising agency of N.W. Ayer & Son was founded. Ayer and Son offered to plan, create, and execute complete advertising campaigns for its customers. By 1900, the advertising agency had become the focal point of creative planning, and advertising was firmly established as a profession. Around the same time, Charles-Louis Havas extended the services of his news agency, Havas, to include advertisement brokerage, making it the first French group to organize. Philadelphia's N. W. Ayer & Son, opened in 1869, was the first full-service agency to assume responsibility for advertising content. At the turn of the century, there were few career choices for women in business; however, advertising was one of the few. Since women were responsible for most of the purchasing done in their household, advertisers and agencies recognized the value of women's insight during the creative process. In fact, the first American advertising to use a "sexual" sell was created by a woman for a soap product. A great turn in consumerism arrived just before the Industrial Revolution. In the nineteenth century, capitalist development and the industrial revolution were primarily

focused on the capital goods sector and industrial infrastructure (e.g., mining, steel, oil, transportation networks). At that time, agricultural commodities, essential consumer goods, and commercial activities had developed but not to the same extent as other sectors. Members of the working classes worked long hours for low wages and little time or money was left for consumer activities. Capital goods and infrastructure were quite durable and took a long time to be used up. Henry Ford and other leaders of industry understood that mass production presupposed mass consumption. After observing the assembly lines in the meat packing industry, Frederick Winslow Taylor brought his theory of scientific management to the organization of the assembly line in other industries which unleashed incredible productivity and reduced the costs of all commodities produced on assembly lines. While previously the norm had been the scarcity of resources, the Industrial Revolution created an unusual economic situation. For the first time in history products were available in outstanding quantities, at outstandingly low prices, being thus available to virtually everyone. So began the era of mass consumption.

1900 Coca-Cola Advertisement

https://www.boundless.com/u-s-history/the-gilded-age-1870-1900/work-in-industrial-america/massmarketing-advertising-and-consumer-culture

American Advertising: A Brief History

Despite or because of its ubiquity, advertising is not an easy term to define. Usually advertising attempts to persuade its audience to purchase a good or a service. But institutional advertising has for a century sought to build corporate reputations without appealing for sales. Political advertising solicits a vote (or a contribution), not a purchase. Usually, too, authors distinguish advertising from salesmanship by defining it as mediated persuasion aimed at an audience rather than one-to-one communication with a potential customer. The boundaries blur here, too. When you log on to Amazon.com, a screen often addresses you by name and suggests that, based on your past purchases, you might want to buy certain books or CDs, selected just for you. A telephone call with an automated telemarketing message is equally irritating whether we classify it as advertising or sales effort. In United States history, advertising has responded to changing business demands, media technologies, and cultural contexts, and it is here, not in a fruitless search for the very first advertisement, that we should begin. In the eighteenth century, many American colonists enjoyed imported British consumer products such as porcelain, furniture, and musical instruments, but also worried about dependence on imported manufactured goods. Advertisements in colonial America were most frequently announcements of goods on hand, but even in this early period, persuasive appeals accompanied dry descriptions. Benjamin Franklins Pennsylvania Gazette reached out to readers with new devices like headlines, illustrations, and advertising placed next to editorial material. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century advertisements were not only for consumer goods. A particularly disturbing form of early American advertisements were notices of slave sales or appeals for the capture of escaped slaves. Historians have used these advertisements as sources to examine tactics of resistance and escape, to study the health, skills, and other characteristics of enslaved men and women, and to explore slaveholders perceptions of the people they held in bondage. Despite the ongoing market revolution, early and mid- nineteenth-century advertisements rarely demonstrate striking changes in advertising appeals. Newspapers almost never printed ads wider than a single column and generally eschewed illustrations and even special typefaces. Magazine ad styles were also restrained, with most publications segregating advertisements on the back pages.

Equally significant, until late in the nineteenth century, there were few companies mass producing branded consumer products. Patent medicine ads proved the main exception to this pattern. In an era when conventional medicine seldom provided cures, manufacturers of potions and pills vied for consumer attention with large, often outrageous, promises and colorful, dramatic advertisements. In the 1880s, industries ranging from soap to canned food to cigarettes introduced new production techniques, created standardized products in unheard-of quantities, and sought to find and persuade buyers. National advertising of branded goods emerged in this period in response to profound changes in the business environment. Along with the manufacturers, other businesses also turned to advertising. Large department stores in rapidly-growing cities, such as Wanamakers in Philadelphia and New York, Macys in New York, and Marshall Fields in Chicago, also pioneered new advertising styles. For rural markets, the Sears Roebuck and Montgomery Ward mail-order catalogues offered everything from buttons to kits with designs and materials for building homes to Americans who lived in the countrysidea majority of the U.S. population until about 1920. By one commonly used measure, total advertising volume in the United States grew from about $200 million in 1880 to nearly $3 billion in 1920. Advertising agencies, formerly in the business of peddling advertising space in local newspapers and a limited range of magazines, became servants of the new national advertisers, designing copy and artwork and placing advertisements in the places most likely to attract buyer attention. Workers in the developing advertising industry sought legitimacy and public approval, attempting to disassociate themselves from the patent medicine hucksters and assorted swindlers in their midst. While advertising generated modern anxieties about its social and ethical implications, it nevertheless acquired a new centrality in the 1920s. Consumer spendingfueled in part by the increased availability of consumer crediton automobiles, radios, household appliances, and leisure time activities like spectator sports and movie going paced a generally prosperous 1920s. Advertising promoted these products and services. The rise of mass circulation magazines, radio broadcasting and to a lesser extent motion pictures provided new media for advertisements to reach consumers. President Calvin Coolidge pronounced a benediction on the business of advertising in a 1926 speech: Advertising ministers to the spiritual side of trade. It is a great power that has been intrusted to your keeping which charges you with the high responsibility of inspiring and ennobling the commercial world. It is all part of the greater work of regeneration and

redemption of mankind. Advertisements, as historian Roland Marchand pointed out, sought to adjust Americans to modern life, a life lived in a consumer society. Since the 1920s, American advertising has grown massively, and current advertising expenditures are eighty times greater than in that decade. New media radio, television, and the Internetdeliver commercial messages in ways almost unimaginable 80 years ago. Beneath the obvious changes, however, lie continuities. The triad of advertiser, agency, and medium remains the foundation of the business relations of advertising. Advertising men and women still fight an uphill battle to establish their professional status and win ethical respect. Perhaps the most striking development in advertising styles has been the shift from attempting to market mass-produced items to an undifferentiated consuming public to ever more subtle efforts to segment and target particular groups for specific products and brands. In the 1960s, what Madison Avenue liked to call a Creative Revolution also represented a revolution in audience segmentation. Advertisements threw a knowing wink to the targeted customer group who could be expected to buy a Volkswagen beetle or a loaf of Jewish rye instead of allAmerican white bread.

http://historymatters.gmu.edu/mse/ads/amadv.html

The Ray Kroc Story

If I had a brick for every time Ive repeated the phrase Quality, Service, Cleanliness and Value, I think Id probably be able to bridge the Atlantic Ocean with them. Ray Kroc How do you create a restaurant empire and become an overnight success at the age of 52? As Ray Kroc said, I was an overnight success all right, but 30 years is a long, long night. Origins: In 1917, 15-year-old Ray Kroc lied about his age to join the Red Cross as an ambulance driver, but the war ended before his training finished. He then worked as a piano player, a paper cup salesman and a multi-mixer salesman.

In 1954 he was surprised by a huge order for 8 multi-mixers from a restaurant in San Bernardino, California. There he found a small but successful restaurant run by brothers Dick and Mac

McDonald, and was stunned by the effectiveness of their operation. They produced a limited menu, concentrating on just a few itemsburgers, fries and beverageswhich allowed them to focus on quality at every step. Kroc pitched his vision of creating McDonalds restaurants all over the U.S. to the brothers. In 1955 he founded the McDonalds Corporation, and 5 years later bought the exclusive rights to the McDonalds name. By 1958, McDonalds had sold its 100 millionth hamburger. A Unique Philosophy: Ray Kroc wanted to build a restaurant system that would be famous for food of consistently high quality and uniform methods of preparation. He wanted to serve burgers, buns, fries and beverages that tasted just the same in Alaska as they did in Alabama. To achieve this, he chose a unique path: persuading both franchisees and suppliers to buy into his vision, working not for McDonalds, but for themselves, together with McDonalds. He promoted the slogan, In business for yourself, but not by yourself. His philosophy was based on the simple principle of a 3-legged stool: one leg was McDonalds, the second, the franchisees, and the third, McDonalds suppliers. The stool was only as strong as the 3 legs. Rewarding Innovation: Ray Kroc believed in the entrepreneurial spirit, and rewarded his franchisees for individual creativity. Many of McDonalds most famous menu itemslike the Big Mac, Filet-O-Fish and the Egg McMuffin were created by franchisees. At the same time, the McDonalds operating system insisted franchisees follow the core McDonalds principles of quality, service, cleanliness and value.

The Roots of Quality: McDonalds passion for quality meant that every single ingredient was tested, tasted and perfected to fit the operating system. As restaurants boomed, the massive volume of orders caught the attention of suppliers, who began taking McDonalds standards as seriously as McDonalds did. As other quick service restaurants began to follow, McDonalds high standards rippled through the meat, produce and dairy industries.Again, Ray Kroc was looking for a partnershipthis time with McDonalds suppliersand he managed to create the most integrated, efficient and innovative supply system in the food service industry. These supplier relationships have flourished over the decades: in fact, many McDonalds suppliers operating today first started business with a handshake from Ray Kroc. Hamburger University: In 1961, Ray launched a training program, later called Hamburger University, at a new restaurant in Elk Grove Village, Illinois. There, franchisees and operators were trained in the scientific methods of running a successful McDonalds. Hamburger U also had a research and development laboratory to develop new cooking, freezing, storing and serving methods. Today, more than 80,000 people have graduated from the program. The End of a Legend: Right up until he died on January 14, 1984, Ray Kroc never stopped working for McDonald's. Even

when he was confined to a wheelchair, he still went to work in the office in San Diego nearly every day. He would keep a hawk's eye over the McDonald's restaurant near his office, phoning the manager to remind him to pick up the trash, clean his lot, and turn on the lights at night. From his passion for innovation and efficiency, to his relentless pursuit of quality, and his many charitable contributions, Ray Krocs legacy continues to be an inspirational, integral part of McDonalds today. Sources 1. Grinding it Out: The Making of McDonalds by Ray A. Kroc, Ray A. Kroc 1977. 2. McDonalds: Behind the Golden Arches by John F. Love John F. Love 1995. 3. aboutmcdonalds.com 2009.

http://www.mcdonalds.com/us/en/our_story/our_history/the_ray_kroc_story.html

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Id Unit Master CalendarDokument4 SeitenId Unit Master Calendarapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- History Fast Food Fantasy Final PaperDokument2 SeitenHistory Fast Food Fantasy Final Paperapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Raft WorksheetDokument1 SeiteRaft Worksheetapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Id Unit Daily Lesson PlansDokument8 SeitenId Unit Daily Lesson Plansapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rubric For History of Fast Food Company PaperDokument1 SeiteRubric For History of Fast Food Company Paperapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- French Idu RubricDokument1 SeiteFrench Idu Rubricapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- It Says I Say So WhatDokument1 SeiteIt Says I Say So Whatapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- History Lesson Plans For Id UnitDokument9 SeitenHistory Lesson Plans For Id Unitapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Mcdonalds ArticleDokument7 SeitenMcdonalds Articleapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ed 321 Id Unit RubricDokument2 SeitenEd 321 Id Unit Rubricapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Culture Fast Food QuizDokument2 SeitenCulture Fast Food Quizapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Self and Peer EvalsDokument1 SeiteSelf and Peer Evalsapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final ProjectDokument1 SeiteFinal Projectapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- FP RubricDokument1 SeiteFP Rubricapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 3 LPDokument1 SeiteWeek 3 LPapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lobbying Anticipation Guide NameDokument1 SeiteLobbying Anticipation Guide Nameapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 2 LPDokument2 SeitenWeek 2 LPapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- WebquestDokument2 SeitenWebquestapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week 1 LPDokument3 SeitenWeek 1 LPapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Employee HandbookDokument4 SeitenEmployee Handbookapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Math Final Project RubricDokument1 SeiteMath Final Project Rubricapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Bacon House MenuDokument1 SeiteThe Bacon House Menuapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week Three Daily ScheduleDokument2 SeitenWeek Three Daily Scheduleapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Week Two Research HandoutDokument5 SeitenWeek Two Research Handoutapi-252254205Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Anthropology and Sociology: Understanding Human Society and CultureDokument39 SeitenAnthropology and Sociology: Understanding Human Society and CultureBeware DawNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ph.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016Dokument35 SeitenPh.D. Enrolment Register As On 22.11.2016ragvshahNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesDokument12 Seiten1 GEN ED PRE BOARD Rabies Comes From Dog and Other BitesJammie Aure EsguerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conducting An Effective Business Impact AnalysisDokument5 SeitenConducting An Effective Business Impact AnalysisDésiré NgaryadjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cognitive and Metacognitive ProcessesDokument45 SeitenCognitive and Metacognitive ProcessesjhenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuitionfees 2 NdtermDokument3 SeitenTuitionfees 2 NdtermBhaskhar AnnaswamyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADokument1 SeiteAvj_174Noch keine Bewertungen

- Las Week1 - Math5-Q3Dokument3 SeitenLas Week1 - Math5-Q3Sonny Matias100% (2)

- 5-Paragraph Essay "The Quote To Chew and Digest"Dokument2 Seiten5-Paragraph Essay "The Quote To Chew and Digest"ElennardeNoch keine Bewertungen

- AI-Enhanced MIS ProjectDokument96 SeitenAI-Enhanced MIS ProjectRomali Keerthisinghe100% (1)

- Admission FormDokument1 SeiteAdmission FormYasin AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2018 Al Salhi Ahmad PHDDokument308 Seiten2018 Al Salhi Ahmad PHDsinetarmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume of Sahed AhamedDokument2 SeitenResume of Sahed AhamedSahed AhamedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9709 w15 Ms 42Dokument7 Seiten9709 w15 Ms 42yuke kristinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rubics CubeDokument2 SeitenRubics CubeAlwin VinuNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Dream CountryDokument7 SeitenMy Dream CountryNazhif SetyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Teaching ProfessionalDokument64 SeitenEnglish Teaching ProfessionalDanielle Soares100% (2)

- Amanda Lesson PlanDokument7 SeitenAmanda Lesson Planapi-2830820140% (1)

- Agriculture Paper1Dokument16 SeitenAgriculture Paper1sjgchiNoch keine Bewertungen

- HG 5 DLL Q3 Module 8Dokument2 SeitenHG 5 DLL Q3 Module 8SHEILA ELLAINE PAGLICAWANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Study Guide: IGCSE and AS/A2 Level 2017 - 2018Dokument45 SeitenStudy Guide: IGCSE and AS/A2 Level 2017 - 2018Shakila ShakiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Led TV in The Classroom Its Acceptability and Effectiveness in The PhilippinesDokument24 SeitenLed TV in The Classroom Its Acceptability and Effectiveness in The PhilippinesGlobal Research and Development Services100% (3)

- Important DatesDokument6 SeitenImportant DatesKatrin KNoch keine Bewertungen

- TM Develop & Update Tour Ind Knowledge 310812Dokument82 SeitenTM Develop & Update Tour Ind Knowledge 310812Phttii phttii100% (1)

- EQ2410 (2E1436) Advanced Digital CommunicationsDokument11 SeitenEQ2410 (2E1436) Advanced Digital CommunicationsdwirelesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elite's NSS Exam 5-Star Series (Reading Mock Papers)Dokument33 SeitenElite's NSS Exam 5-Star Series (Reading Mock Papers)Chun Yu ChauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benchmarks From The Talent Development Capability Model 2023 q2 With SegmentsDokument10 SeitenBenchmarks From The Talent Development Capability Model 2023 q2 With Segmentspearl.yeo.atNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidebook For All 2020 - 2021 PDFDokument125 SeitenGuidebook For All 2020 - 2021 PDFZegera MgendiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Newsletter 1982 460Dokument12 SeitenNewsletter 1982 460api-241041476Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pack Your Bags: Activity TypeDokument3 SeitenPack Your Bags: Activity TypeBurak AkhanNoch keine Bewertungen