Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Scott Bader-Saye - Islamic Banking, Microfinance, Monte Di Pieta!

Hochgeladen von

Rh2223dbCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Scott Bader-Saye - Islamic Banking, Microfinance, Monte Di Pieta!

Hochgeladen von

Rh2223dbCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

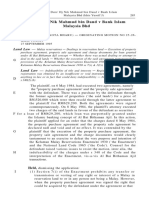

Disinterested Money: Islamic Banking, M onti di Piet, and the Possibility o f Moral Finance

Scott Bader-Saye

T h e curre n t e c o n o m ic crisis a ro s e in la rg e part f r o m fin a n c ia l activities in w h ic h capital w a s p ractically a nd log ically a lie n a te d f r o m real e c o n o m y . This e ssay e x a m in e s the e x p lo ita tiv e logic o f m o d e r n f in a n c e w h i l e c o n s id e rin g t w o a lte rn a tive m o d e l s m ic ro fin a n c e and Islam ic b a n k in g .T h e s e m o d e ls will be c on s ide red a gain st th e b ackdrop o f m e d ie v a l a r g u m e n t s o v e r usury, nota b ly the d eb ates b e tw e e n Franciscans and D o m in ic a n s s u rro u n d in g th e lending institutions k n o w n as m o n ti d i p ie t . W h i l e n oting t h a t e ith e r m o d e l is dec ide d ly p re fe ra b le to c urre n t n o r m a tiv e b a n k ing practices, this essay a rg u e s f o r the in terest-free logic o f Islam ic f in a n c e a g a in s t th e logic o f u su ry ins o fa r as u su ry lends itself to a d o u b le a lie n a tio n o f le n d e r f r o m b o r r o w e r and o f profit fro m value.

IF T H E ALIENATION OF T H E W ORKER WAS CHARACTERISTIC OF the rise of nineteenth-century industrial capitalism, one might say that the alienation of capital is characteristic of twenty-first-century finance capitalism. N ot only is it characteristic, it is arguably the defining trait of the global economy and a root cause of the recent housing and credit crisis. In a 2010 blog post for the Harvard Business Review, Chris Meyer and Julia Kirby ask, Is the alienation of capital what s fundamentally to blame for the Great Recession?1 In this essay I explore their question in both theoretical and practical terms. The theoretical task is to analyze and critique the history by which capital came to be severed from real value, specifically tracing this alienation to its most primal form in the practice of lending at interest. The practical task is to consider how peopie of faith might change our banking and investing habits so as to promote new models of lending and borrowing, credit and collaboration. These new models do not need to be created from scratch, as there are various forms of alternative finance currently existing that would benefit greatly from our willingness to move our money out of the megabanks and into no- or low-interest cooperative

Scott Bader-Saye, PhD, is professor of Christian ethics and moral theology, Sem inary of the Southwest, 501 E. 32nd St., A ustin,TX, 78705; scott.bader-saye@ ssw.edu.

Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics, 33,1 (2013): 119-138

120

Disinterested Money

endeavors. The question is whether we are sufficiently convinced of the economic good of these projects that we are willing to accept a potentially smaller slice of the investment pie. The argument proceeds in three parts. First, I examine the exploitative logic of modern finance, understood as a set of alienating practices. Second, I consider a particularly significant late-medieval argument about usury in which Franciscans and Dominicans weighed in on the lending institutions known as monti di piet. Third, I introduce two contemporary alternative models of financemicrofinance and Islamic bankingas present-day heirs to the Franciscan and Dominican logics. While noting that either model is decidedly preferable to current normative banking practices, I argue that the interest-free logic of Islamic finance goes farther in protecting the goods of lending and borrowing than even socially conscious models of microfinance, which necessarily give assent to interest (though minimal) and thus fail to protect sufficiently against usury s double alienationof lender from borrower and of profit from value.

Speculation: The Alienation of Capital from Real Economy Meyer and Kirby use the phrase alienation of capital to critique speculative investing, which separates capital from assets and production in the real economy. They pointedly ask, Is the alienation of capital what s fundamentally to blame for the Great Recession?2 Their answer emerges from a brief sketch of the shifts undergone in finance over the last fifty years. Their analysis is worth quoting at length. For most of the 20th Century, financial institutions were engaged in aggregating our society s savings to meet its own demands for productive capacity, to build the goods needed for a higher standard of living. . . . But as the industrial revolution aged, the opportunities to earn high returns by financing capital-intensive innovation became insufficient to absorb the available financial resources. Consequently, the financial institutions turned to other sources of profitfirst fees, the initial incentive for securitization, but then the trading of financial instruments and their various derivatives. Now, the tail has come to wag the dog. In the US today, the trillions of dollars of annual trading in financial assets dwarfs the market capitalization of operating companies.... Those profits were not primarily generated by the value-adding work of supporting investments in real sector companies but from the zero-sum work of trading financial instruments. The result is that capital has become alienated from its value and purpose. Originally intended to enable the increased productivity of the society through investment in productive capacity, it has lost its connection to value creation of any non-financial kind. Con-

Scott Bader-Saye

121

sequently, the financial services industry itself becomes alienated from the rest of society, because its work no longer benefits its customers.3 In this account, Meyer and Kirby pinpoint the fault lines in modern finance that made possible the current economic crisis. Instead of investing in worthy projects and funding productivity, monetary capital has been captured by the lure of speculation, made possible by financial products that detach or alienate capital from productive work in the real economy.4 The transition from value-adding investment to zero-sum trading led to the leveraging of vast quantities of commercial deposits for high-stakes gambling in the derivatives market. This shift was seen most clearly in the subprime mortgage crisis, in which loans were made to homebuyers based on inflated home values and without concern for whether the borrower was able to repay the loan. W hat became important was simply that the loan was made, because, more often than not, the mortgage company would take its profit in fees and sell off the loan to a larger investment bank. Those banks were not concerned about the bad loans because they, in turn, packaged the loans into securities for resale, hiding their risk with triple-A ratings from agencies that were paid by the very banks that needed the high rating. These securities were, again, repackaged into collateralized debt obligations (CDO), which were sliced and resold. These CDOs were then bet against through derivative trading (at times being bet against by the very institutions selling the CDO to its customers).5 And through it all billions of dollars were made. A vast emerald city of sleight-of-hand wealth production lay behind the curtain at Bank of America, JP Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Wells Fargo, Morgan Stanley, and Goldman Sachs. We began hearing these machinations of the financial industry described as daisy chains, Ponzi schemes, and casino capitalism.6 My favorite analogy, though, is the children s game hot potato, for as long as the bad loans could be repackaged and resold, everyone made moneyuntil the defaults began, and someone got stuck with the hot potato, and the game came to an unhappy end. The majority of the monetary exchanges occurring during the housing boom were not about buying houses but about buying, selling, and betting on the debt itself. These zero-sum exchanges floated above the real economy, failing to add value or create good. One must add, of course, that subprime banking practices were only successful because there were borrowers ready to purchase homes that exceeded their means. The arrangement was symbiotic in this wayeach player imagining they could benefit from a system in which profit could be produced without value being added. One of the conditions that set the stage for this scheme to flourish was the 1999 repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, a postdepression regulation that had created the FDIC and separated investment banks from deposit banks.7 T he

122

Disinterested Money

repeala truly bipartisan affair, undertaken by a Republican congress and signed by President Clintonleft the FDIC in place, thus guaranteeing that the government would insure deposits up to, at the time, one hundred thousand dollars. But it repealed the regulation separating the world of commercial banks (where most of us have our FDIC-insured checking and savings accounts) from that of investment banks (which are involved with securities, insurance, hedge funds, and other derivatives). The repeal thus allowed the creation of megabanks that began to gamble with deposits that were guaranteed by the government. There was no real incentive not to speculate wildly, since the government (that is, the taxpayers) bore much of the risk. William Safire, despite being a self-described libertarian conservative, wrote a prescient op-ed in the New York Times in 1998 opposing the repeal of Glass-Steagall. He wrote, Federal deposit insurance, protecting a bank s depositors, should not become a subsidy protecting the risks taken by non-banking affiliates. He added, Let s not be in such a big rush to knock down barriers. The Government s biggest financial mistake of the past generation was to raise deposit insurance to $100,000 while allowing housing [Savings and Loans] to plunge into commercial lending. T hat all but removed the element of risk from foolish or corrupt loans and helped bring on the [Savings and Loans] debacle. Good fences make good banks.8 The increasing alienation of capital we have seen in the last ten years has been sparked by policies that ereate an incentive for risky derivative trading by guaranteeing that taxpayers will pay back the lossesprecisely what we saw happening in 2008.

Usury: The Alienation of Money from Value While particular shifts in policy and regulation over the last dozen years have magnified the alienation of capital, I argue that the roots of alienation are much deeper. The detachment of investment capital from real productive lending (the concern of Meyer and Kirby) builds on a more fundamental detachment of money from value. If we look back far enoughsay, to Thomas Aquinas or further back to Aristotlewe see that money is understood as a functional mediator of exchange.9 One used money to describe or designate the intrinsic value of goods or labor in order to facilitate just transactions. Notably, labor and goods were assumed to have intrinsic value apart from the assignment of a monetary price, and so money was not the content of value but the marker of value. Over time this assumption changes as money, especially paper money, which is but an elaborate IOU, begins to fly free of any connection to intrinsic value, resulting in the exchange of debt as currency.10 As Philip Goodchild writes, money veil[s] the source of the value of values.1 1 In other words, money comes to function not as a marker of intrinsic value in something else but as

Scott Bader-Saye

123

the assignment of extrinsic value based on human desire and will or, put another way, the fluctuations of the market. So what occurs is not simply that money is separated from its relation to intrinsic value, but money tends to gobble up all value such that nothing really has value until it has a price. This modern shift in the relation of money and value parallels and supports the rise of liberal politics. In a polity that lacks common agreement on goods that is, on the worth or value of particular things, actions, or pursuitsmoney fills the void by representing naked, generic value. Money does not suggest any particular end that should be pursued, yet it does suggest that whatever goods or ends one might pursue must be exchangeable with money, that is, they must have a price; and so a monetized liberalism produces a state in which all are free to create and pursue their own goods so long as those goods are amenable to commodification, that is, reducible to a single scale represented by money. In this way money becomes that which both grants and measures worth, a point made quite nicely by Goodchild: To achieve what one values, one must value money first as the means of access to what one desires. Since it is the means by which all other social values may be realized, it posits itself as the supreme value. Nothing is more liquid, more exchangeable, or more valuable than money. Whatever one s own values, one must value money first as the means of access to all other values.1 2 The end result of these successive alienations is that we tend to think of things no longer in terms of their nature, which carries with it an inalienable worth, but in terms of their value, which is reduced to monetary terms. Money essentially replaces nature as a means of codifying worth.1 3 The ramifications of this change are quite stark and not a little disturbing. For example, Aquinas held that the nature of something provided an important limit on how we could use it: ownership was a good as long as we understood that there were limits upon use and these limits were determined in part by the nature of the thing.14 But if the nature of the thing is replaced by its value, which is then reduced to money, there is no limit on how we use things except a limit imposed by cost. So we would likely not use a valuable vase for target practice nor neglect to care for an expensive racehorse but this limit is only a matter of fiscal responsibility, not necessarily respect for the nature of the thing. This relation of money and value might be illuminated by a brief reflection on the popular PBS program Antiques Roadshow. This program is a kind of reality show that involves a judgment of value but, unlike Dancing with the Stars or American Idol, what is being judged is not a person or a performance but an object. Ordinary people who seek to know the history, provenance, and value of something they own bring their household treasures and artifacts to be appraised by the Roadshow experts. T he standard storyline involves an object that has been in the family for a long time, has been in storage or at least largely forgotten about, and has been rediscovered by an owner

124

Disinterested Money

who begins to wonder what this object is really worth. Part of what is interesting is the way in which the show s self-description belies the true narrative arc of the program. T he show s website, for instance, includes a Teacher s Guide that suggests using the show as a way to engage students in the world of material culture.1 5 Through this program students will engage history, geography, the arts and society in order to gain new insights and a sense of wonder about the people and events of the past, the present, and perhaps the future.16 The expressed goals of the show thus suggest primary attention to intrinsic worth, the nature of the thing itself, yet if you have watched the show you will know that the dramatic tension centers around the question of dollar value, and the climax of the dramatic arc is the revealing of the monetary worth of the item. In the ensuing denouement, the owners ponder what they will do with the item, often speaking of it no longer as mom s old necklace but as an investment. One gets the impression that by attaching a monetary value to the antique, the expert has revealed some deep truth, indeed, has clarified its real worth. It is as if the very nature of the item has somehow been converted into capital.1 7 Thus far we have been tracking the conditions of alienation that form the background of our current economic crisis from the changes in finance over the last fifty years to the changes in the relation of money and value over the last five hundred years. My argument is not that money of necessity creates alienation from real value. Certainly money can serve a proper and useful function of mediating and marking intrinsic values in relation to one another. N or am I saying that intrinsic value is self-evident upon the surface of a thing, for there will always be a need to negotiate and discern the value of something.18 Rather, I am pointing out the way that money has come to fill a gap that opened in modernity when we culturally, politically, and philosophically became suspicious of a transcendent good and a given nature, which were the fundamental assumptions upon which intrinsic value rested. The contemporary triumph of speculation over investment and the modern detachment of money from value simply extend the logic already presupposed in the ancient (yet widely regulated or prohibited) practice of usury, understood here in its classical sense to include all lending at interest. Interest is perhaps the original alienation of capital because it represents money earned that is dissociated from any particular production of real value. Rather than functioning as a true investment partnership, in which the risks of gain and loss are shared and linked to real economic output, interest income severs the link to productivity. It demands a guaranteed repayment that is not indexed to value gained by the project for which the money was lent. The question of usury, then, is not just a question of justice, fairness, or concern for the poor, though it is certainly that; it is a question of how we conceive of the relation between money and value.

Scott Bader-Saye

125

The Old and New Testaments reject usury based on the exploitation of the poor and are largely silent on the question of lending for commercial ventures.19 Lacking specific biblical commands regarding commercial lending, it is not surprising that medieval theologians turned to Aristotle and natural law to help them think through the logic of usury as applied to the context of a developing market economy. If the point of lending was to help another create a profitable enterprise, what was the harm in asking for interest on the loan? Aristotle makes the case that usury is not simply unjust in its exploitation of the poor; it is unnatural. He argues that it is the most hated sort of moneymaking because it makes a gain out of money itself, and not from the natural object of it. For money was intended to be used in exchange, but not to increase at interest. And this term interest [tokos, or offspring], which means the birth of money from money, is applied to the breeding of money because the offspring resembles the parent. Wherefore of all modes of getting wealth this is the most unnatural.20 The production of wealth is not against nature, but usury is contrary to nature because it allows of no natural limit and it separates gain from any productive contribution to the wider economy of human goods. Usury was the original alienation of capital, and if we are to think about faithful responses to the economy of our day, we cannot ignore the fundamentally problematic relation of money, value, and profit that occurs whenever lending at interest is allowed. Yet even while recognizing this problem, Christian history complicates any simple repudiation of usury, insofar as such lending has, at times, been undertaken precisely in service of the poor. As an example, we might turn to the rise of the monti di piet in fifteenth-century Europe, institutions that engaged in what we might call late-medieval microfinance.

Faithful Lending in the Middle Ages: Franciscans, Dominicans, and the Monti di Piet The monti di piet were lending institutions established by the church and, especially in Italy, supported by the Franciscans. The monti were founded as charitable funds to serve as an alternative to exploitative lending practices.21 The idea was to provide service to the less poor of the poor sometimes called the fat paupers (pauperes pinguioris), who needed financial support but not charity.22 The loans were backed by the security of pawned objects. Sustaining this in-between form of support proved difficult because on the one hand it required a fee to support institutional costs, leading to the charge that this fee was just usury by another name, yet on the other hand it did not promise a return to investors, leading to a struggle to maintain an adequate supply of

126

Disinterested Money

capital. In other words, the enterprise from the start faced both theoretical and practical challenges. The theoretical challenge came especially from the Dominicans (following Aquinas) who charged the Franciscans with back-door usury. Although initially no interest was returned to depositors (and thus no profit was made from the loans), the very act of charging an administrative fee, usually about 5 percent of the loan, smacked of usury by another name.23 The Franciscans countered that the fee was canonically acceptable since it staved off the disastrous consequences of borrowing from the exploitative moneylenders of the day.24 The question rested on whether usury was problematic insofar as it was exploitative (which the monti sought assiduously to avoid) or whether it was problematic because it was, in Aristotle s terms, unnatural. If usury was against nature, then no charitable intentions could make the practice good or just. If usury denied the proper divine ordering of exchange, any attempt to use it for good would ultimately be undermined and turned back to exploitation. The Franciscans had already formulated a response to this charge in the thirteenth century in the person of Peter Olivi (1248-98). Olivi s famous passage on usury occurs in his treatise, De usuris. When someone, at a time when it is usually worth less, as a special favour offers or sells grain which he firmly intended to store and sell at a time usually and probably more costly, he may charge the same price which at the time of offer or sale is thought likely to obtain at the more costly time. . . . And the reason why he may sell or exchange it at that price is both because he to whom it is offered ought to provide him with probable equivalence or preserve him from loss of probable gain, and because that which in the firm intendon of its owner is ordained to some probable gain does not only possess the character of money or a thing straightforward but beyond this a certain seminal reason of profitability which we usually call capital, and therefore not only must its own value simply be repaid but also an added value over and above it. From this it also follows that when someone offers money with which it is firmly intended to trade, to someone else entirely of charity and because of his need, on the agreement that he shall gain or lose as much as a similar sum gains or loses with such a merchant of equal worth, then he does not commit usury, but rather grants a certain favour, albeit keeping himself indemnified.2 5 W hat is novel here is the way in which Olivi applies the concept of seminal reason (rationes seminales) to money. He is drawing on an Augustinian notion, appropriated from Stoic and Neoplatonic thought, in which material things contain the seeds of what they would or could develop into over time.26 For Augustine, seminal reason existed in the nature of a thing itself, so he made use of this concept, for instance, in his doctrine of creation.27 But for Olivi, the sem-

Scott Bader-Saye

127

inal reason of money exists not in the money but in the human intention to use the money in a profit-making enterprise. Olivi, like his later Franciscan brothers Duns Scotus and William of Ockham, displays a nominalist understanding of the relation of nature and will that allows him to substitute a willed intention for a natural inclination, thus declaring natural the use of money to ereate money based on the human will to use capital for profit. On this account usury is not against nature and thus not an intrinsically disordered act. Rather, it is a neutral act with respect to nature, though morally it must be bound by standards of justice and concern for the poor. To be fair, we should remember that Olivi, like other scholastic authors of economic handbooks, sought to provide practical advice for those treading the dangerous waters of trade and commerce. His goal was to provide workable guidelines for practitioners rather than to create an apology for capitalistic enterprise.28 Olivi s work was no doubt helpful as the Franciscans sought to initiate a practical and sustainable alternative to the usurious exploitation of the poor. Nonetheless, this does not diminish the fact that Olivi was attempting to give theoretical justification to the alienation of capital. He could, of course, have had no idea that the logic of a seminal reason of profitability in money could lead to unbridled derivative trading, the triumph of speculation over investment, and a global economic crisis. So, while it would not be fair to call Olivi a proto-capitalist, it may well be true that he was a proto-nominalist, laying down an ontology that would undergird the soon-to-emerge market economy. Alongside this theoretical challenge to charging interest on money, the monti di piet faced the practical challenge of sustaining the necessary capital to make the loans when there was no interest returned on the deposit. It was precisely this challenge that doomed an early attempt to found a monte in London in 1361. Bishop Michael Nothburg contributed one thousand marks of silver to establish an institution, essentially a pawnshop, for the purpose of lending money to the poor without interest. He instructed that the institutional expenses be paid out of the original capital. But lacking any return on the loans, the capital was consumed by operating costs and the bank was closed.29 This short-lived experiment made clear the difficulty of sustaining intermediate institutions that were not simply charitable (reliant on the perpetual goodwill of donors) but neither were they usurious (reliant on a guaranteed return for investors). In the mid-fifteenth century farther experiments emerged in Italy, beginning in Perugia in 1462 and eventually growing to more than two hundred establishments across the county.30 In many ways these monti proved to be forerunners of modern banks, providing a link between medieval moneychangers and modern financial institutions.3 1 The monte of Florence provides a particularly interesting example of the challenges that faced these charitable projects. W hen the

128

Disinterested Money

Florentine monte opened in 1495, the monte or mound of capital was collected from charitable donations with no promise of gain from the use of the money.32 The loans were limited to small amounts, and if any funds remained after covering expenses, the monte was required to give the excess to charity. The problem, as Bishop Nothburg had discovered in 1361, was how to sustain the necessary capital to cover the demand for loans. Over time the leaders in Florence began to make use of taxation and legal fines to fund the monte, although its largest early contribution came from the selling of goods confiscated during the war with Pisa in 1498.3 3 The Bolognese monte was able to attract sufficient funds by securing a plenary indulgence from Pope Julius II for all who contributed to its charitable work.34 Despite all of these measures, the monte continually struggled for funding and eventually, in the 1530s, the Florentine monte began paying a 5 percent return on investment to attract capital.35 This guaranteed return had the result of attracting a large surplus of capital that then became an irresistible temptation to the duke, Cosimo de Medici, who began ordering the monte to make large loans to kin, clients, fanctionaries, and important foreigners.36 His ability to authorize low-interest loans at will allowed him to build favor and influence, and it became an important part of both his foreign and domestic policy. O f course his actions did not go unnoticed, but the Dominicans, already critics of the monte, were effectively silenced when Cosimo declared [the monastery of San Marco] and two other Dominican houses forfeit and confiscated their property.37 Thus the monte began to grow into something that looked much less like a charitable endeavor than a financial arm of the state with administrative structures that were set to evolve into a modern banking institution.38 For those of us seeking alternatives to the exploitations of contemporary finance capitalism, the legacy of the monti di piet cannot but be ambiguous. On the one hand, the practice of providing inexpensive loans to the poor suggests a striking alternative to our current system in which the poor, if they can get loans at all, are charged the highest rates for borrowing. On the other hand, the Franciscan logic at work in the justification of the monti opens the theoretical door to the very logic of alienated capital that we need to unmask and displace. The history of the Florentine monte and its eventual capitulation to the Medicis and their powerful allies, suggests that in practice such enterprises can easily be exploited, and charitable intentions can be overtaken by the lure of profit.

Faithful Lending Today: Microfinance As I hinted earlier, there is more than a little similarity between the mission of the monti di piet and the contemporary work of microfinance. Like the monti

Scott Bader-Saye

129

of their day, microfinance enterprises seek to provide affordable loans to the poor who would otherwise be denied credit or charged exorbitant rates.39 Institutions such as Muhammad Yunus s Grameen Bank in Bangladesh seek a sustainable way to embody a social vision, a vision not just for the care of the poor through charity but for the development of the poor through small loans that can seed worthy projects and create dignified work. Yunus sounds almost like a fifteenth-century Franciscan when he writes, In the past, financial institutions always asked themselves, Are the poor credit-worthy? and always answered no. As a result, the poor were simply ignored and left out of the financial system, as if they didnt exist. I reversed the question: Are the banks people-worthy? W hen I discovered they were not, I realized it was time to ereate a new kind of bank.40 N ot surprisingly, though, just as Cosimo de Medici saw the Florentine monti as an opportunity to extend his wealth and power, so the wider banking world has come to see microfinance as an opportunity for profit. A recent report noted, As nonprofits proved the world s poor to be reliable clients, many of these same institutions transformed into for-profit lenders or banks, and rapidly expanded their outreach, along with their profits. Their financial success pointed the way for traditional banks and for-profit agencies to move into the market, thereby increasing competition.41 In the last few years, two large microfinance institutions, Mexico s Compartamos Banco and India s SKS Microfinance Ltd., profited from successful initial public offerings, calling into question the charitable aura that had surrounded microfinance.42 In addition, irresponsible borrowing has at times left the poor with debts they cannot repay. A lack of communication and regulatory oversight has produced a situation in which a single borrower might receive loans from several microcredit organizations without any of them knowing about the other loans.43 Muhammad Yunus himself has lamented, W hen microfinance spread across the world, some people abused it. Some went berserk. In my opinion, if there is any personal profit involved, it should not be called microfinance, which should be totally devoted to the benefit of poor people. People used the respect for microfinance. In every country where there was microfinance they needed proper regulatory authorities to oversee the sector and legislation to define it. I knew that the sector was crippled by an inadequate legal framework.44 If microfinance is going to provide an alternative, nonexploitative model of lending and borrowing, it will need to lean heavily on the state to regulate practices and maintain the social vision that spawned the movement. This need illuminates the danger inherent in lending at interest, even minimal interest, as it will always be prone to abuse by those who see an opportunity to make money out of money. One interesting parallel between Yunus s work in microcredit and the medieval Franciscan project is that both faced challenges from those within their

130

Disinterested Money

tradition who charged them with unlawful lending. In Islam, as in medieval Christianity, any charging of interest, riba, is considered prohibited, haram, by the Sharia. Thus, despite the charitable intentions of Yunus s work, many scholars of Islamic finance say that his model is inconsistent with the prohibition of riba.45 In what follows I outline briefly an Islamic model of interestfree finance in order to sketch one more alternative to alienated capital, an alternative that shares with the medieval Dominicans a prohibition on lending at interest.

Faithful Lending Today: Islamic Banking Islam is the only Abrahamic tradition that has preserved its prohibition on usury. As such, it provides an interesting contrast to Western banking practices that have become accepted by Jews and Christians. Further, it provides a vision of what might have arisen in Christian countries if the Dominicans had won the medieval debate. Most of us consider interest-based lending to be part of the invisible background of our lives; we make use of banking services, save for college, and build pension funds with little or no thought about the practical or conceptual apparatus in which we are participating. But for Muslims, the issue is different. T he prohibition against usury in the Q uran was never set aside or superseded by later developments, so riba remains forbidden. The central Q uranic passages are found in Surahs 2 and 3. Those who eat Riba (usury) will not stand (on the Day of Resurrection) except like the standing of a person beaten by Shaitan (Satan) leading him to insanity. That is because they say: Trading is only like Riba (usury), whereas Allah has permitted trading and forbidden Rib (usury). So whosoever receives an admonition from his Lord and stops eating Rib (usury) shall not be punished for the past; his case is for Allah (to judge); but whoever returns [to Rib (usury)], such are the dwellers of the Firethey will abide therein. Allh will destroy Rib (usury) and will give increase for Sadaqt (deeds of charity, alms, etc). (Surah 2:275-76) O you who believe! Eat not Rib (usury) doubled and multiplied, but fear Allh that you may be successful. (Surah 3:13 0)46 The image in both of these passages of eating interest is quite striking. Whereas trade participates in an organic flow of goods constituted by mutually beneficial exchanges at its best, usury is hungry for prey and it devours value. This visceral image seems to get at much of what Meyer and Kirby meant by alienation of capital. Sharia law, drawing on these passages as well as the tra-

Scott Bader-Saye

131

ditions of the sunnah and the hadith, maintains a prohibition on lending at interest, but not on lending itself. Indeed, lending, renting, investing, and all kinds of commerce are encouraged, but lending at interest is considered to be fandamentally unjust.47 Medieval Islamic scholar al-Ghazali (1058-1 111) expressed the logic of the prohibition in terms that will likely sound familiar to readers of Thomas Aquinas. He writes, One who practices usury on dirhams and dinars is denying the bounty of God and is a transgressor, for these coins are created for other purposes and are not needed for themselves. When someone is trading in dirhams and dinars themselves, he is making them as his goal, which is contrary to their fanetions. Money is not created to earn money, and doing so is a transgression. The two kinds of money are means to acquire other things; they are not meant for themselves. In relation to other goods, dirhams and dinars are like prepositions in a sentenceused to give proper meaning to words; or like a mirror reflecting colors but having no color of its own. If a person is permitted to sell (or exchange) money with money (for gain), then such transactions will become his goal, and thus money will be imprisoned and hoarded. Imprisonment of the ruler or postman is a transgression, for then they are prevented from performing their functions; the same with money.48 Al-Ghazali uses wonderful images here to explain money s nature and limits. Money is a preposition linking other words; money is a mirror reflecting the value of something else; money invested for interest is money pulled out of the natural and humanly beneficial flow of economy and so is like taking a prisoner. The similarity here to Thomas Aquinas should not really surprise us, since Thomas may well have read al-Ghazali when he was studying at the University of Naples, and both writers were relying heavily on Aristotle s account of money in the Politics (despite al-Ghazali s fervent criticisms of the philosophers).49 But while Aquinas s rejection of usury became a relic in Christian theology, al-Ghazali s became a lasting account of a binding legal prohibition. If Muslims were to be involved in trade, commerce, and finance, they would have to find a way to do it without charging riba. The solution was to stop thinking in terms of selling or renting money and to think in terms of collaborative partnerships. So in the case of a loan to finance a business venture, the lender and borrower each contribute something to the endeavor and each share in some portion of the profit or loss, referred to as profit and loss sharing, or PLS. Such partnerships are encouraged because by extending credit to worthy projects they support the creation of some good in the economy. O f course, these partnerships cannot be aimed at the production of or participation in things forbidden in the Sharia, such as alcohol, pornography, or gambling.

132

Disinterested Money

This arrangement avoids the primary injustice of lending at interest, which is the unequal distribution of risk. W hen a lender requires, say, a 5 percent return on a loan, that amount is set regardless of whether the real sector asset, the business project, makes a profit or not. Thus, an interest-based contract guarantees a set return to the lender regardless of the profit or loss on the part of the borrower. T he risk is not evenly shared. The lender, who has the money, is in a position of power and should not use that power to coerce a guaranteed profit while shifting all of the risk to the borrowing partner. Thus, the principie of PLS opens a way to imagine finance that maintains a human relation, cares about what the money is used for, shares risk equitably, and limits coercion and exploitation by those with financial power. Once again, to leap back to the Middle Ages, this Islamic model of PLS echoes a brief comment Aquinas makes in his discussion of usury in the Summa theologica. He who lends money transfers the ownership of the money to the borrower. Hence the borrower holds the money at his own risk and is bound to pay it all back: wherefore the lender must not exact more. On the other hand he that entrusts his money to a merchant or craftsman so as to form a kind of society, does not transfer the ownership of his money to them, for it remains his, so that at his risk the merchant speculates with it, or the craftsman uses it for his craft, and consequently he may lawfully demand as something belonging to him, part of the profits derived from his money.50 Here Aquinas makes the same logical distinction that we find in Sharia-compliant finance. T hat is, while one cannot justly ask someone to pay more for money than the value of the money itself, one can participate in a business partnership to form a kind of society in which both lender and borrower risk possible loss but also share in possible gain. W hat we seem to be seeing here is that the economic wisdom shared among Christian and Muslim thinkers in the Middle Ages has been preserved by Islam but left behind by the Christian churches. Hayat Khan, among others, makes the point that Islamic finance would have provided protections against the forms of speculation and debt that led to our current global financial crisis. He argues that if every nominal activity were married to a real activity then one could not earn money on money without linking it to a real project.5 1 But this divorce of the nominal and the real, what we have called the alienation of capital, was at the heart of the system that crashed. Moreover, if the Islamic requirement that people can sell only what they actually own were enforced, this restriction would have prohibited the securitization of mortgages and thus would have protected against the creation of a speculative meta-economy composed of hedges and derivatives.52 It may be that once interest is allowed into the system there is no log-

Scott Bader-Saye

133

ical point at which to stop its growth; regulations cannot help but appear arbitrary as they shift with the political winds. While PLS and riba-frtz finance may seem well and good for commercial lending, how would one buy a house, since a house is not a business venture and is not intended to make profit? Would PLS apply in this case and, if not, where would the financing come from? Islamic home financing is handled in several different ways, but for the sake of example I will present the one used by the largest Islamic financing house in the country, LARIBA (whose name means no riba). Yahia Abdul-Rahman, the banks founder, observes, My job as a banker is not to dig a deeper hole of debt for my customer.53 W hat LARIBA does, essentially, is create a contract with the buyer in which the house is jointly purchased, and then the bank, who owns the majority of the home, rents the home to the buyer on a rent-to-own plan in which the profit for the bank and its depositors comes from rental income, not interest. Some would say this plan is simply a work-around, another way to make profit off of borrowing without calling it interest. Indeed, there are internal arguments among Islamic scholars about what types of home financing may or may not be Sharia-compliant, and it is not my place nor is it within my expertise to weigh in on those debates. However, by working out a financing arrangement according to a riba-free logic, certain things are different about these contracts that mitigate the kinds of problems we have seen in the recent housing crisis. The first benefit is that riba-free financing rules out adjustable rate mortgages or balloon mortgages. Thus, one of the main reasons for foreclosures, a sudden steep increase in payments, cannot happen. The second benefit is that these mortgages cannot be securitized into CDOs, so cannot be caught up in the Ponzi-like trading of debt we have seen in recent years.54 This limitation dissolves any incentive for the finance house to tempt borrowers into loans that are beyond their means. The third benefit is that LARIBA mortgages are indexed to rental prices, which, based on use-value, do not tend to bubble like house prices. Thus, if the comparable rental value is low but the price of the house is high, LARIBA will refuse to grant financing because it is a sign that the price of the house has bubbled above its actual value. Because of this indexing to rental value, LARIBA has steered clear of the morass that has faced many US banks. Islamic finance sets forth a vision of economic cooperation that not only coheres with Christian thinking through much of the church s history but also provides a real alternative to the unbridled speculation that feeds the boom and bust cycle that has given us the savings and loan crisis of the 1980s, the dotcom bubble of the 1990s, and the housing crash of the 2000s. And while some continue to see Sharia regulation as holding back the development of Islamic states, it may well be that the temperate care with money urged by scholars of Islamic finance could allow for a slower, longer-term development that is not as prone to bubble, bust, and stratified wealth as is Western capitalism.55

134

Disinterested Money

Conclusion I have argued that Meyer and Kirby are right to highlight the alienation of capital as a chief contributor to our current economic crisis. I have further argued that the alienation of capital is not simply a recent problem but has arisen through a long series of changes in economic thought and practice, one of the most significant being the decision by the church to embrace, or at least allow for, lending at interest. While many inside and outside the church would agree that our current system of finance is ordered toward exploitation, there is less agreement on what alternatives we can offer. I have suggested that those of us concerned to think about banking and investing practices as acts of discipleship might look to either the Franciscan or the Dominican path for a faithful alternative. The Franciscan path might lead us to advocate for microfinance, offering low-interest loans to empower the poor while creating sustainable structures that can attract sufficient capital for sustainability. We might throw our support (and our money) behind projects such as Kiva, Microplace, and the Grameen Foundation while contributing to the work of organizations such as the Center for Responsible Lending.56 Closer to home we might move our money into credit unions such as Self-Help, which recently partnered with Citi Community Development to extend their Micro Branch program serving lower-income communities as an alternative to payday lenders and expensive check-cashing services.57 At the same time we would need to be aware that the interests of profit can foil even the best intentions. The rush of traditional investors into the microfinance market suggests that present-day Cosimos stand at the door ready to seek advantage at the expense of the poor. Such dvolution in microfinance can be guarded against but cannot be entirely prevented once one has opened up to the logic of interest-based lending. The Dominican path might lead us to attend closely to the Islamic alternative of riba-free lending. The riba-free logic of Islamic finance more fully protects lending practices against the double alienation of lender from borrower and of profit from value. By assuring that all commercial lending is investing (that is, a shared partnership in risking profit and loss) rather than speculation (that is, a predetermined return that alienates the lender from true partnership with the borrower and the commercial venture), Islamic finance has resources to avoid being captured as the next hot for-profit scheme. Further, Christian support for Islamic finance would serve as a bridge-building endeavor, linking Christians, Muslims, and other people of faith in an enterprise of faith-based economy. Near the end of his Theology of Money Philip Goodchild proposes, There is nothing necessary about the existing institution of capitalist credit money. There is nothing to prevent the invention of new forms of credit, contract, and

Scott Bader-Saye

135

exchange, for the current system, institutionalized effectively in the Bank of England and copied around the world, was constructed to resolve a set of theological, political, and economic problems. At the end of modernity, our problems have changed.58 It is at least worth a hard look at whether the principles of Islamic finance might provide just such an alternative model of credit, contract, and exchange that can extend beyond Islamic partners to include all of those who are concerned with socially responsible, humanly accessible, common-good-driven institutions. At the very least, there is no reason for Christians or Muslims to allow our money to be used by megabanks in service of goals that are foreign to our vision of human flourishing.

Notes

1. Chris Meyer and Julia Kirby, The Alienation o f Capital, Harvard Business Review, HBR Blog Network (March 30, 2010), http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2010/03/alienation_of_capital .html. Note these statistics on the growing profits o f the US finance industries: From 1973 to 1985, the financial sector never earned more than 16 percent of domestic corporate profits. In 1986, that figure reached 19 percent. In the 1990s, it oscillated between 21 percent and 30 percent, higher than it had ever been in the postwar period. This decade, it reached 41 percent. Pay rose just as dramatically. From 1948 to 1982, average compensation in the financial sector ranged between 99 percent and 108 percent of the average for all domestic private industries. From 1983, it shot upward, reaching 181 percent in 2007. Simon Johnson, The Quiet Coup, Atlantic, May 2009, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/ archive/2 009/05/the-quiet-coup/7 364/. 2. Meyer and Kirby, Alienation of Capital. 3. Ibid. 4. On the need for a recovery of investment over against speculation, see Umair Haque, The Betterness M anifesto, Harvard Business Review , HBR Blog Network, May 20, 2010, http://blogs.hbr.org/haque/2010/05/the_betterness_manifesto.html. 5. Jesse Eisinger and Jake Bernstein, The Magnetar Trade: H ow One Hedge Fund Helped Keep the Bubble Going, Pro Publica, April 9, 2010, www.propublica.org/article/themagnetar-trade-how-onehedge-fund-helpedkeep-the-housing-bubble-going/single. 6. See The C D O Daisy Chain, Pro Publica, August 26, 2010, www.propublica.org/special/ the-cdo-daisy-chain. 7. See Frontline, The Long Demise of Glass-Steagall, PBS, www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/ frontline/shows/wallstreet/weill/demise.html. In their article, Parsons Blames Glass-Steagall Repeal for Crisis, Kim Chipman and Christian Harper quote the former chair of the board of Citigroup, Richard Parsons, saying, To some extent what we saw in the 2007, 2008 crash was the result of the throwing off o f Glass-Steagall. Parsons resigned from the Citigroup board on April 17, 2012. H e had served for sixteen years. Chipman and Harper also note that John S. Reed, the former Citicorp CEO . . . said in 2009 that he regretted working to overturn Glass-Steagall. Kim Chipman and Christine Harper, Parsons Blames Glass-Steagall Repeal for Crisis, Bloomberg, April 19, 2012, www.bloomberg .com/news/2 012 -04-19/parsons-blames-glass-steagall-repealfor-crisis.html. 8. William Safire, D ont Bank on It, New York Times, April 16, 1998, www.nytimes.com/ 1998/04/16/opinion/essay-don-t-bank-on-it.html.

136

Disinterested Money

9. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, I, 5 and V, 5, in Introduction to Aristotle, trans. W. D. Ross, ed. Richard McKeon (New York: Random House, 1947); and Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologica, II-II, Q. 78, art. 1, trans. Fathers of the English Dominican Province (Allen, TX: Christian Classics, 1948). 10. Philip Goodchild, Theology of Money (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2009), 7-10. 11. Ibid., 7. 12. Ibid., 12. 13. Ibid., 221-24. 14. Aquinas, Summa theologica, II-II, Q. 66. 15. PBS, Teachers Guide: Antiques Roadshow, May 29, 2012, www.pbs.org/wgbh/ roadshow/teachers.html. 16. Ibid. 17. O f course, this is not the only conclusion to draw from the show, as there are certainly instances in which the owner of the object, having discovered the monetary value (i.e., the value in relation to other values), pledges to take greater care of the artifact and respect the intrinsic value that has now been marked by (not caused by) the monetary appraisal. Thanks to one of the JSCE reviewers for saving me from overstating my case. 18. As Aquinas notes, the just price of things is not fixed with mathematical precision, but depends on a kind of estimate, so that a slight addition or subtraction would not seem to destroy the equality of justice. Summa theologica, II-II, Q. 77, art. 1. 19. In both the Old and N ew Testaments regulations involving lending are treated as questions of how to care for the poor. For instance, Exodus 22:25: If you lend money to my people, to the poor among you, you shall not deal with them as a creditor; you shall not exact interest from them. See Mark E. Biddle, Biblical Prohibition against Usury, Interpretation 65, no. 2 (April 1, 2011): 117-27. H e writes, The biblical injunction against usury, then, clearly does not address the issue primarily from the standpoint of the needs of commerce, financial policy, or a coherent economic theory, but with an interest in social justice. It intends not to regulate a market economy but to nurture the health o f a community by protecting its weakest members. (122). 20. Aristotle, Politics, 1.10, in Introduction to Aristotle, translated by Benjamin Jowett, edited by Richard McKeon (New York: Random House, 1947). 21. Though it is not the point o f this paper, it must be noted that the monti were also founded to provide an excuse to put the Jewish moneylenders out o f business and, in some cases, to force them out of the cities. T he charitable intentions were thus married to less noble ones, contributing to the complexity of evaluating the endeavor. See Carol Bresnahan Menning, The M onte s M onte: The Early Supporters o f Florences M onte di Piet, Sixteenth Century Journal 23, no. 4 (1992): 662-63. 22. Joel Mokyr, ed., The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History, vol. 4 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 1. 23. Ibid.; see also Carol Bresnahan Menning, Loans and Favors, Kin and Clients: Cosimo de Medici and the M onte di Piet, Journal of Modern History 61, no. 3 (September 1989): 490. 24. Menning, Loans and Favors, 664. This debate continued until, at the Fifth Lateran Council in 1515, Pope Leo X in a papal bull sided with the Franciscans and opened the door for canonically allowed lending at interest. 25. Peter Olivi, De usuris, Dubium 6, translated by Giacomo Todeschini, cited in Odd Langholm, Economics in the Medieval Schools (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 1992), 371.

Scott Bader-Saye

137

26. Ibid. 27. Odd Langholm, Economics in the Medieval Schools, 371. 28. Ibid., 353. 29. U. Benigni, Montes Pietatis, in The Catholic Encyclopedia, edited by Charles G. Herbermann, Edward A. Pace, Cond B. Pallen, Rt. Rev. Thomas J. Shahan, and John J. Wynne (New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911); available at N ew Advent, www.newadvent .org/cathen/105 34d.htm. 30. Menning, M ontes M onte,661 . 31. Ibid. 32. Menning, Loans and Favors, 490. 33. Menning, M onte s M onte, 671-73. 34. Ibid., 668. 35. Ibid., 672. 36. Menning, Loans and Favors, 493. 37. Ibid, 494. 38. Ibid, 510-11. 39. Muhammad Yunus, Building Social Business (New York: Public Affairs, 2010), vii-xiv. 40. Muhammad Yunus, Creating a World without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism (New York: Public Affairs, 2007), 49. 41. KnowledgeWharton, What Went Wrong with Microfinance? Time, March 14, 2012, http://business.time.com/2012/03/14/what-went-wrong-with-microfinancing/. 42. Ibid. 43. Ibid. 44. Quoted in Madeleine Bunting, Muhammad Yunus Banks on Beating the Enemies o f Microfinance, Guardian, July 18, 2011, www.guardian.co.uk/world/201 l/jul/18/ muhammadyunus-microfinance-bangladesh; see also Vikas Bajaj, Microlenders, Honored with N o bel, Are Struggling, New York Times, January 5, 2011, www.nytimes.com/2011/01/06/ business/global/06micro.html. 45. This is not to say that Islamic scholars are not interested in providing Sharia-compliant models to do the work of microfinance. As Mohd Shahrulnizam Abd Hamid o f the International Centre o f Education in Islamic Finance (www.inceif.org) notes, T he model introduced by Muhammad Yunus and later followed by many countries and associations throughout the world is using interest-based loans. H ow to make them Shariah compliant? There are [a] few ways to offer Shariah compliant Micro financing products to the poor. As elevating poverty is a concern in Islam, we need to design Shariah compliant Micro financing so the poor have the chance to get out from poverty without engaging in riba. Mohd Shahrulnizam Abd Hamid, Shariah Compliant Sales and Riba-Based Transactions: A Comparison, A cademia.edu, http://inceif.academia.edu/ M ohdShahrulnizam /Papers/2 715 3 7/Shariah_C om pliant_Sales_and_R iba-B ased_ Transactions_A_Comparison. 46. Translations from the King Fahd Complex for Printing the H oly Quran, www.quran complex.com/Quran/Targama/Targama.asp?nSora=2 &l=eng&nAya=2 75#2_2 7 5. 47. Fuad Al-Omar and Mohammed Abdel-Haq, Islamic Banking: Theory, Practice, and Challenges (Karachi, Pakistan: Oxford University Press, 1996), 1-20. 48. Al-Ghazali, Ihya Ulum al-Din, 4:192, cited in S. M. Ghazanfar, The Economic Thought of Abu Hamid Al-Ghazali and St. Thomas Aquinas: Some Comparative Parallels and

138

Disinterested Money

Links, in S. M. Ghazanfar, ed., Medieval Islamic Economic Thought (London: Routledge, 2003), 198. 49. Ibid. 50. Aquinas, Summa theologica, II-II, Q. 78, art. 2, reply to obj. 5. 51.Hayat Khan, Bringing Morality into Finance: T he Principles o f Sharia Law, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, June 23, 2009, www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2009/06/19/ 2605107.htm. See also Faheem Younus, H ow Islam Can Eliminate the US D ebt, Huffington Post, August 1, 2011, www.huffingtonpost.com/faheem-younus/islam-and-debt_b_ 914618.html. 52. Khan, Bringing Morality into Finance. 53. Yahia Abdul-Rahman, Muslim Mortgages, Interview, American Public Media , Marketplace, March 8, 2008, www.marketplace.org/topics/business/middle-east-work/muslimmortgages. 54. See Khan, Iliasu, and Chowdry, who note that the conventional securitization and financing setup [of residential mortgage backed securities] is in stark contrast with IF [Islamic Finance] principles that require a clear line of sight between the capital, the security and the productive assets. Instruments that derive value based on parsed cash flows from assets are not permissible because cash flows, per se are not considered assets. The irony is that conventional markets use the term asset-backed security (ABS) while never linking these securities to real assets. So strong is the emphasis on maintaining linkages and preserving ownership of productive assets that IF principles even disallow multiple instruments to be derived from a single asset. IF also provides no profit incentive for debt trading, since debt can only be traded at par value, eliminating a secondary debt market where linkages, risk exposure and ownership could become unclear. Waleed Khan, Fatimah IIiasu, and Sajjad Chowdry, Preventing Residential Mortgage Crises: An Islamic Finance Perspective, SSRN eLibrary, 2009, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfmPabstract_id 1481984. 55. See, for instance, Timur Kuran, The Long Divergence: How Islamic Law Held Back the M iddie East (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010). 56. See Kiva, www.kiva.org; Microplace, https://www.microplace.com; the Grameen Foundation, www.grameenfoundation.org; and the Center for Responsible Lending, www .responsiblelending.org. 57. See Self-Help Credit Union, www.self-help.org. 58. Goodchild, Theology of Money, 239.

Copyright and Use:

As an ATLAS user, you may print, download, or send articles for individual use according to fair use as defined by U.S. and international copyright law and as otherwise authorized under your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. No content may be copied or emailed to multiple sites or publicly posted without the copyright holder(sV express written permission. Any use, decompiling, reproduction, or distribution of this journal in excess of fair use provisions may be a violation of copyright law.

This journal is made available to you through the ATLAS collection with permission from the copyright holder( s). The copyright holder for an entire issue of ajournai typically is the journal owner, who also may own the copyright in each article. However, for certain articles, the author of the article may maintain the copyright in the article. Please contact the copyright holder(s) to request permission to use an article or specific work for any use not covered by the fair use provisions of the copyright laws or covered by your respective ATLAS subscriber agreement. For information regarding the copyright holder(s), please refer to the copyright information in the journal, if available, or contact ATLA to request contact information for the copyright holder(s). About ATLAS: The ATLA Serials (ATLAS) collection contains electronic versions of previously published religion and theology journals reproduced with permission. The ATLAS collection is owned and managed by the American Theological Library Association (ATLA) and received initial funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The design and final form of this electronic document is the property of the American Theological Library Association.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Desai, Mihir. 2023. The Crypto Collapse and The Magical Thinking That Infected Capitalism.Dokument9 SeitenDesai, Mihir. 2023. The Crypto Collapse and The Magical Thinking That Infected Capitalism.woiaf.ethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Financial Crisis: Reflections On TheDokument2 SeitenFinancial Crisis: Reflections On ThebhundofcbmNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ank Otes: Confusing Capitalism With Fractional Reserve BankingDokument11 SeitenAnk Otes: Confusing Capitalism With Fractional Reserve BankingMichael HeidbrinkNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Wall Street Matters - Cohan's InsightsDokument25 SeitenWhy Wall Street Matters - Cohan's Insightsjorge camilo ibañez cardenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Economic Crisis Matttick JRDokument31 SeitenEconomic Crisis Matttick JRAnonymous mOdaetXf7iNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Misunderstanding Financial Crises", A Q&A With Gary Gorton - FT AlphavilleDokument7 Seiten"Misunderstanding Financial Crises", A Q&A With Gary Gorton - FT AlphavilleAloy31stNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Big Short Case StudyDokument5 SeitenThe Big Short Case StudyMaricar RoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2008 Walking Down The FailureDokument10 Seiten2008 Walking Down The FailureJames BradleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inside Job - Financial Crisis Klara KomenDokument1 SeiteInside Job - Financial Crisis Klara KomenKlaraKomenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avoiding The Next CrisisDokument12 SeitenAvoiding The Next CrisisChe VasNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Wall Street Journal Guide to the End of Wall Street as We Know It: What You Need to Know About the Greatest Financial Crisis of Our Time—and How to Survive ItVon EverandThe Wall Street Journal Guide to the End of Wall Street as We Know It: What You Need to Know About the Greatest Financial Crisis of Our Time—and How to Survive ItNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary: I.O.U.: Review and Analysis of John Lanchester's BookVon EverandSummary: I.O.U.: Review and Analysis of John Lanchester's BookNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reinventing Banking: Capitalizing On CrisisDokument28 SeitenReinventing Banking: Capitalizing On Crisisworrl samNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kregel Subprime Levy Jan 2008Dokument31 SeitenKregel Subprime Levy Jan 2008caduzinhoxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Matt Taibbi The Big TakeoverDokument21 SeitenMatt Taibbi The Big Takeovergonzomarx100% (1)

- Global Fraud-Global Hope by Paul HellyerDokument14 SeitenGlobal Fraud-Global Hope by Paul HellyerChristopher Porter100% (1)

- PT AdiDokument3 SeitenPT AdiLiana MoisescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Locavesting: The Revolution in Local Investing and How to Profit From ItVon EverandLocavesting: The Revolution in Local Investing and How to Profit From ItBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (3)

- Reflections On Finance and The Good Society: Obert HillerDokument9 SeitenReflections On Finance and The Good Society: Obert HillerPrasanth KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wray 2008. Financial Markets Meltdown. What Can We Learn From MinskyDokument53 SeitenWray 2008. Financial Markets Meltdown. What Can We Learn From MinskyppphhwNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marxist Economics Jason UnruheDokument194 SeitenMarxist Economics Jason Unruhebiorox00xNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where's The Money To Come From??Dokument32 SeitenWhere's The Money To Come From??kronblom100% (1)

- Why Capital Structure Matters - WSJDokument5 SeitenWhy Capital Structure Matters - WSJShweta K DhawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Social Licence for Financial Markets: Reaching for the End and Why It CountsVon EverandThe Social Licence for Financial Markets: Reaching for the End and Why It CountsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Collection Units 1 3Dokument46 SeitenCredit Collection Units 1 3elle gutierrezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityDokument8 SeitenWall Street Lies Blame Victims To Avoid ResponsibilityTA WebsterNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Circuiting Hyper-InflationDokument26 SeitenShort Circuiting Hyper-InflationDaniel SaarinenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 07.10.07 Volcker On ReformDokument8 Seiten07.10.07 Volcker On Reform1236howardNoch keine Bewertungen

- 9.islamic Finance - An Alternative Financial System For Stability, Equity, and GrowthDokument46 Seiten9.islamic Finance - An Alternative Financial System For Stability, Equity, and GrowthHarsono Edwin PuspitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The House of CardsDokument42 SeitenThe House of Cardsramesm38Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Financial Crash - Who Was To BlameDokument4 SeitenThe Financial Crash - Who Was To BlameHuy NguyenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Where Is Capitalism HeadedDokument22 SeitenWhere Is Capitalism HeadedMarcelo AraújoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of CDOs in Subprime CrisisDokument6 SeitenThe Role of CDOs in Subprime CrisisKunal BhodiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Speculating On Everyday Life: The Cultural Economy of The QuotidianDokument16 SeitenSpeculating On Everyday Life: The Cultural Economy of The QuotidianlucianaeuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exposing Mammon: Devotion To Money in A Market Society (Philip Goodchild)Dokument11 SeitenExposing Mammon: Devotion To Money in A Market Society (Philip Goodchild)mrwonkishNoch keine Bewertungen

- BaselineScenario TestimonyJECApril202009FINALDokument11 SeitenBaselineScenario TestimonyJECApril202009FINALZerohedgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ellen Brown 25022023Dokument6 SeitenEllen Brown 25022023Thuan TrinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pirates of Manhattan II Highway To SerfdomDokument4 SeitenThe Pirates of Manhattan II Highway To SerfdomStephon Lynch0% (1)

- Ninth Harvard Forum on Islamic Finance Explores 2008 Financial CrisisDokument25 SeitenNinth Harvard Forum on Islamic Finance Explores 2008 Financial CrisisKind MidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- February 26, 2008. "Unconventional Observations For Unconventional Problems"Dokument5 SeitenFebruary 26, 2008. "Unconventional Observations For Unconventional Problems"api-236467720Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2008-09-26 BuggyBanksDokument5 Seiten2008-09-26 BuggyBanksJoshua RosnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Taming Wildcat StablecoinsDokument49 SeitenTaming Wildcat StablecoinsForkLogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faith in The Numbers 9-4robertsDokument9 SeitenFaith in The Numbers 9-4robertsDuarte Rosa FilhoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Inside JobDokument5 SeitenInside Jobpkb0% (1)

- The Night They Reread Pozsar (In His Absence)Dokument7 SeitenThe Night They Reread Pozsar (In His Absence)Konjac NativeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Great Global Debt PrisonDokument4 SeitenThe Great Global Debt Prisonjas2maui100% (1)

- TIE W08 FinSafetyNetDokument14 SeitenTIE W08 FinSafetyNetRadhya KhairifarhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crisis Economics Nouriel RoubiniDokument1 SeiteCrisis Economics Nouriel Roubiniaquinas03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cooper 2015 - Shadow Money and The Shadow WorkforceDokument30 SeitenCooper 2015 - Shadow Money and The Shadow Workforceanton.de.rotaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Credit Supernova!: Investment OutlookDokument0 SeitenCredit Supernova!: Investment OutlookJoaquim MorenoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Join CAT groups and prepare with CAT-O-PEDIADokument118 SeitenJoin CAT groups and prepare with CAT-O-PEDIAManish JhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wae Bffe:Wh C Bea Gdadb D: Term SheetDokument4 SeitenWae Bffe:Wh C Bea Gdadb D: Term SheetnumerounojaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- This Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00Dokument74 SeitenThis Content Downloaded From 154.59.124.141 On Mon, 18 Sep 2023 10:17:18 +00:00skywardsword43Noch keine Bewertungen

- Notes Austerity BlythDokument4 SeitenNotes Austerity BlythPan PapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper - CDOs and CDSsDokument10 SeitenPaper - CDOs and CDSsIvan LovreNoch keine Bewertungen

- MGT301 Assignment Abhinav Singhal 2010111069Dokument3 SeitenMGT301 Assignment Abhinav Singhal 2010111069Abhinav SinghalNoch keine Bewertungen

- EMF BookSummary VolumeI Digital 1008Dokument48 SeitenEMF BookSummary VolumeI Digital 1008VaishnaviRavipatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role and Identity of Church in Biblical Story PDFDokument26 SeitenRole and Identity of Church in Biblical Story PDFRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Systematic Theology Michael Williams PDFDokument38 SeitenSystematic Theology Michael Williams PDFRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mission As The Key To The Biblical StoryDokument4 SeitenMission As The Key To The Biblical StoryRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Maqasid Al-Shari Ah and The Role of The Financial System in Realizing TheseDokument23 SeitenThe Maqasid Al-Shari Ah and The Role of The Financial System in Realizing TheseAmine ElghaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Theological DimensionDokument14 SeitenThe Theological DimensionRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marc Cortez Creation and Context WestminsterDokument15 SeitenMarc Cortez Creation and Context WestminsterRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- James Alison - Taking The PlungeDokument3 SeitenJames Alison - Taking The PlungeRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Braulik - Law As Gospel in Torah LawDokument11 SeitenBraulik - Law As Gospel in Torah LawRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- David Kotter Ayn Rand Research Article3 PDFDokument44 SeitenDavid Kotter Ayn Rand Research Article3 PDFRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Woodyard-Is Greed Good - Catholic Analysis!! (Very Good)Dokument44 SeitenWoodyard-Is Greed Good - Catholic Analysis!! (Very Good)Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interest in The Catholic Tradition - (Dickinson Quote)Dokument6 SeitenInterest in The Catholic Tradition - (Dickinson Quote)Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vincent - Prohibition On Usury in All Traditions Including Islam!Dokument48 SeitenVincent - Prohibition On Usury in All Traditions Including Islam!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sauer-Christian Faith, Economy, Ethics (On John Calvin)Dokument9 SeitenSauer-Christian Faith, Economy, Ethics (On John Calvin)Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Smoker - Modern Usury - and Credit Cards (Very Good) !Dokument28 SeitenSmoker - Modern Usury - and Credit Cards (Very Good) !Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Halteman - Productive Capital and Christian Moral Teaching!Dokument13 SeitenHalteman - Productive Capital and Christian Moral Teaching!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schreiner - Review of Webb's RMHDokument19 SeitenSchreiner - Review of Webb's RMHRh2223db100% (1)

- Vincent - Prohibition On Usury in All Traditions Including Islam!Dokument48 SeitenVincent - Prohibition On Usury in All Traditions Including Islam!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interest in The Catholic Tradition - (Dickinson Quote)Dokument6 SeitenInterest in The Catholic Tradition - (Dickinson Quote)Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Significance of Luther's Hermeneutics!Dokument22 SeitenSignificance of Luther's Hermeneutics!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Peter Olivi and Papal Inerancy!Dokument14 SeitenJohn Peter Olivi and Papal Inerancy!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Development of Catholic Social TeachingDokument32 SeitenDevelopment of Catholic Social TeachingRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Maqasid Al-Shari Ah and The Role of The Financial System in Realizing TheseDokument23 SeitenThe Maqasid Al-Shari Ah and The Role of The Financial System in Realizing TheseAmine ElghaziNoch keine Bewertungen

- Brian McCall - Unprofitable Lending ChapterDokument65 SeitenBrian McCall - Unprofitable Lending ChapterRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voss-Five Essential Hermeneutic Practices - Very GoodDokument14 SeitenVoss-Five Essential Hermeneutic Practices - Very GoodRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Self Other and God in AfricaDokument11 SeitenSelf Other and God in AfricaRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becker Historical CriticalDokument36 SeitenBecker Historical CriticalRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- God Benefactor and PatronDokument29 SeitenGod Benefactor and PatronRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Wilson - Sources and Methods in The Study of Ancient Near East!Dokument10 SeitenWilson - Sources and Methods in The Study of Ancient Near East!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literal Interpretation Stallard!Dokument11 SeitenLiteral Interpretation Stallard!Rh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Andy Woods - Historical GrammaticalDokument14 SeitenAndy Woods - Historical GrammaticalRh2223dbNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case 17 Nik Mahmud V BimbDokument14 SeitenCase 17 Nik Mahmud V BimbFirdaus DarkozzNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5903 18966 2 PBDokument20 Seiten5903 18966 2 PBBerliana PrahestiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Proposa Title Page KonjitDokument12 SeitenResearch Proposa Title Page KonjitSolomon Tekalign100% (2)

- Islamic Finance: Attractive For Non-Muslims?Dokument22 SeitenIslamic Finance: Attractive For Non-Muslims?adinda1999Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reference BikashDokument15 SeitenReference Bikashroman0% (1)

- Daood Abdullah S/o Abdul Karim: About MeDokument3 SeitenDaood Abdullah S/o Abdul Karim: About MeFaisal NasirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sharia Insurance Perspective in IndonesiaDokument24 SeitenSharia Insurance Perspective in IndonesiaI GEDE WIYASANoch keine Bewertungen

- Takaful Companies and Products in MalaysiaDokument55 SeitenTakaful Companies and Products in MalaysiaMohammed AlshuaibiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cimb Islamic Tier 2 IMDokument92 SeitenCimb Islamic Tier 2 IMkasman.ffaNoch keine Bewertungen

- تقييم جودة اداء وسائل الاستثمار الرابحة المضاربة المشاركة الايجارة المنتهية بالتمليك في البنوك الاسلامية الاردنيةDokument151 Seitenتقييم جودة اداء وسائل الاستثمار الرابحة المضاربة المشاركة الايجارة المنتهية بالتمليك في البنوك الاسلامية الاردنيةMazen BobNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Revival of the Islamic Gift EconomyDokument10 SeitenThe Revival of the Islamic Gift EconomyNatsu DeAcnologiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muslim ContributionsDokument171 SeitenMuslim ContributionsAhmed Rahmanovic100% (4)

- Level of Waqf Awareness Among The People of BangsaDokument13 SeitenLevel of Waqf Awareness Among The People of Bangsaibraheem alaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Consumption EcoDokument29 SeitenConsumption EcoNur Fatehah Nadira Mohd FauziNoch keine Bewertungen

- 45 ..Islamic BankingDokument47 Seiten45 ..Islamic BankingShaguftaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Critique of Creative Shari'Ah Compliance in The Islamic Finance Industry-Brill (2017)Dokument301 SeitenA Critique of Creative Shari'Ah Compliance in The Islamic Finance Industry-Brill (2017)roytanladiasanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meezan Bank Report FinalDokument61 SeitenMeezan Bank Report FinalMuhammad JamilNoch keine Bewertungen

- WEBINAR-LAPENKOP@2021 - Ustadz Mursalin Maggangka, P.HDDokument33 SeitenWEBINAR-LAPENKOP@2021 - Ustadz Mursalin Maggangka, P.HDcooperative inovatorsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Role and Responsibilities of Shariah Advisor To Strengthen The Shariah Compliance FrameDokument10 SeitenRole and Responsibilities of Shariah Advisor To Strengthen The Shariah Compliance Frameoma1100Noch keine Bewertungen

- Bank Alfalah Islamic Banking Division Internship ReportDokument26 SeitenBank Alfalah Islamic Banking Division Internship Reportsaba123aslamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soneri Annual Report 2017 FINALDokument172 SeitenSoneri Annual Report 2017 FINALaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training Material: Structuring Islamic Financial ProductsDokument7 SeitenTraining Material: Structuring Islamic Financial Productsnina11190Noch keine Bewertungen

- Example Finance Dissertation Topic 11Dokument12 SeitenExample Finance Dissertation Topic 11AfriyantiHasanahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isl Amic Social Finance:: Realities and ProspectsDokument8 SeitenIsl Amic Social Finance:: Realities and ProspectsNama SayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management in Arab WorldDokument10 SeitenManagement in Arab WorldRahulMotipalleNoch keine Bewertungen

- BEXIMCO SUKUK ProspectusDokument376 SeitenBEXIMCO SUKUK ProspectusSajjad HossainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meezan Bank AbidDokument67 SeitenMeezan Bank Abidim.abid1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fatawa 2006 Jobs and WorksDokument34 SeitenFatawa 2006 Jobs and WorksISLAMIC LIBRARYNoch keine Bewertungen

- Glossary of Islamic Finance TermsDokument4 SeitenGlossary of Islamic Finance TermsElmelki AnasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Overview of Financial Services Act 2013Dokument11 SeitenOverview of Financial Services Act 2013FatehahNoch keine Bewertungen