Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Cardio Pulm Resuscitation

Hochgeladen von

daniphilip777Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Cardio Pulm Resuscitation

Hochgeladen von

daniphilip777Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

CARDIO-PULMONARY RESUSCITATION

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) consists of the use of chest compressions and artificial ventilation to maintain circulatory flow and oxygenation during cardiac arrest. Indications and contraindications CPR should be performed immediately on any person who has become unconscious and is found to be pulseless. Loss of effective cardiac activity is generally due to the spontaneous initiation of a nonperfusing arrhythmia, sometimes referred to as a malignant arrhythmia. The most common nonperfusing arrhythmias include the following: Ventricular fibrillation (VF) Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) Pulseless electrical activity (PEA) Asystole Pulseless bradycardia Cardiac arrest

CPR should be started before the rhythm is identified and should be continued while the defibrillator is being applied and charged. Additionally, CPR should be resumed immediately after a defibrillatory shock until a pulsatile state is established. Contraindications The only absolute contraindication to CPR is a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order or other advanced directive indicating a persons desire to not be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest. A relative contraindication to performing CPR is if a clinician justifiably feels that the intervention would be medically futile. Equipment CPR, in its most basic form, can be performed anywhere without the need for specialized equipment. Universal precautions (ie, gloves, mask, gown) should be taken. However, CPR is delivered without such protections in the vast majority of patients who are resuscitated in the out-of-hospital setting, and no cases of disease transmission via CPR delivery have been reported. Some hospitals and EMS systems employ devices to provide mechanical chest compressions. A cardiac defibrillator provides an electrical shock to the heart via 2 electrodes placed on the patients torso and may restore the heart into a normal perfusing rhythm.

Technique In its full, standard form, CPR comprises the following 3 steps, performed in order: Chest compressions Airway Breathing For lay rescuers, compression-only CPR (COCPR) is recommended. Positioning for CPR is as follows: CPR is most easily and effectively performed by laying the patient supine on a relatively hard surface, which allows effective compression of the sternum Delivery of CPR on a mattress or other soft material is generally less effective The person giving compressions should be positioned high enough above the patient to achieve sufficient leverage, so that he or she can use body weight to adequately compress the chest For an unconscious adult, CPR is initiated as follows: Give 30 chest compressions Perform the head-tilt chin-lift maneuver to open the airway and determine if the patient is breathing Before beginning ventilations, look in the patients mouth for a foreign body blocking the airway Chest compression The provider should do the following: Place the heel of one hand on the patients sternum and the other hand on top of the first, fingers interlaced Extend the elbows and the provider leans directly over the patient (see the image below) Press down, compressing the chest at least 2 in Release the chest and allow it to recoil completely The compression depth for adults should be at least 2 inches (instead of up to 2 inches, as in the past) The compression rate should be at least 100/min The key phrase for chest compression is, Push hard and fast Untrained bystanders should perform chest compressiononly CPR (COCPR) After 30 compressions, 2 breaths are given; however, an intubated patient should receive continuous compressions while ventilations are given 8-10 times per minute This entire process is repeated until a pulse returns or the patient is transferred to definitive care

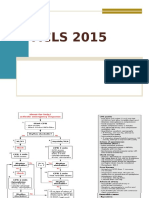

To prevent provider fatigue or injury, new providers should intervene every 2-3 minutes (ie, providers should swap out, giving the chest compressor a rest while another rescuer continues CPR Ventilation If the patient is not breathing, 2 ventilations are given via the providers mouth or a bag-valve-mask (BVM). If available, a barrier device (pocket mask or face shield) should be used. To perform the BVM or invasive airway technique, the provider does the following: Ensure a tight seal between the mask and the patients face Squeeze the bag with one hand for approximately 1 second, forcing at least 500 mL of air into the patients lungs To perform the mouth-to-mouth technique, the provider does the following: Pinch the patients nostrils closed to assist with an airtight seal Put the mouth completely over the patients mouth After 30 chest compression, give 2 breaths (the 30:2 cycle of CPR) Give each breath for approximately 1 second with enough force to make the patients chest rise Failure to observe chest rise indicates an inadequate mouth seal or airway occlusion After giving the 2 breaths, resume the CPR cycle Complications Complications of CPR include the following: Fractures of ribs or the sternum from chest compression (widely considered uncommon) Gastric insufflation from artificial respiration using noninvasive ventilation methods (eg, mouth-to-mouth, BVM); this can lead to vomiting, with further airway compromise or aspiration; insertion of an invasive airway prevents this problem ACLS In the in-hospital setting or when a paramedic or other advanced provider is present, ACLS guidelines call for a more robust approach to treatment of cardiac arrest, including the following: Drug interventions ECG monitoring Defibrillation Invasive airway procedures Emergency cardiac treatments no longer recommended include the following:

Routine atropine for pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole Cricoid pressure (with CPR) Airway suctioning for all newborns (except those with obvious obstruction) Image library

Delivery of chest compressions. Note the overlapping hands placed on the center of the sternum, with the rescuer's arms extended. Chest compressions are to be delivered at a rate of at least 100 compressions per minute.

Background For patients with cardiac arrest, survival rates and neurologic outcomes are poor, though early appropriate resuscitation, involving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), early defibrillation, and appropriate implementation of postcardiac arrest care, leads to improved survival and neurologic outcomes. Targeted education and training regarding treatment of cardiac arrest directed at emergency medical services (EMS) professionals as well as the public has significantly increased cardiac arrest survival rates.[1] CPR consists of the use of chest compressions and artificial ventilation to maintain circulatory flow and oxygenation during cardiac arrest. A variation of CPR known as hands-only or compression-only CPR (COCPR) consists solely of chest compressions. This variant therapy is receiving growing attention as an option for lay providers (that is, nonmedical witnesses to cardiac arrest events). The relative merits of standard CPR and COCPR continue to be widely debated. An observational study involving more than 40,000 patients concluded that standard CPR was associated with increased survival and more favorable neurologic outcomes than COCPR was.[2] However, other studies have shown opposite results, and it is currently accepted that COCPR is superior to standard CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Several large randomized controlled and prospective cohort trials, as well as one meta-analysis, demonstrated that bystander-performed COCPR leads to improved survival in adults with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, in comparison with standard CPR.[3, 4, 5] Differences between these results may be attributable to a subgroup of younger patients arresting from noncardiac causes, who clearly demonstrate better outcomes with conventional CPR.[2] The 2010 revisions to the American Heart Association (AHA) CPR guidelines state that untrained bystanders should perform COCPR in place of standard CPR or no CPR (see American Heart Association CPR Guidelines).[6] Of the more than 300,000 cardiac arrests that occur annually in the United States, survival rates are typically lower than 10% for out-ofhospital events and lower than 20% for in-hospital events.[7, 8, 9, 10, 11] A study by Akahane et al suggested that survival rates may be higher in men but that neurologic outcomes may be better in women of younger age, though the reasons for such sex differences are unclear.[12] Additionally, studies have shown that survival falls by 10-15% for each minute of cardiac arrest without CPR delivery.[13, 14] Bystander CPR initiated within minutes of the onset of arrest has been shown to improve survival rates 2- to 3-fold, as well as improve neurologic outcomes at 1 month.[15, 16] It has also been demonstrated that out-of hospital cardiac arrests occurring in public areas are more likely to be associated with initial ventricular fibrillation (VF) or pulseless ventricular tachycardia (VT) and have better survival rates than arrests occurring at home.[17] This article focuses on CPR, which is just one aspect of resuscitation care. Other interventions, such as the administration of pharmacologic agents, cardiac defibrillation, invasive airway procedures, postcardiac arrest therapeutic hypothermia,[18, 19, 20, 21, 22] the use of echocardiography in resuscitation,[23] and various diagnostic maneuvers,[24, 25] are beyond the scope of this article. For more information, see the Resuscitation Resource Center; for specific information on the resuscitation of neonates, see Neonatal Resuscitation. American Heart Association CPR guidelines In 2010, the Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee (ECC) of the AHA released the Associations newest set of guidelines for CPR. Changes for 2010 include the following[24, 26] : The initial sequence of steps is changed from ABC (airway, breathing,

chest compressions) to CAB (chest compressions, airway, breathing), except for newborns Look, listen, and feel is no longer recommended The compression depth for adults should be at least 2 inches (instead of up to 2 inches) The compression rate should be at least 100/min Emergency cardiac treatments no longer recommended include routine atropine for pulseless electrical activity (PEA)/asystole, cricoid pressure (with CPR), and airway suctioning for all newborns (except those with obvious obstruction). Postcardiac arrest care is covered in a new section[27] Several studies that looked at the quality of CPR being performed in hospitals and by EMS systems found that providers often did not perform CPR up to the standards of the ECC guidelines.[28, 29, 30, 31] Specifically, they found that providers were often deficient in both rate and depth of chest compressions and often provided ventilations at too high a rate. Other studies demonstrated the impact of inadequate rate and depth on survival.[32] The 2010 AHA guidelines state that untrained bystanders should perform COCPR (previous AHA guidelines did not address untrained bystanders separately).[6] Several studies concluded that stopping compressions in order to give ventilations may be detrimental to the patients outcome.[33, 34, 35] While a bystander halts compressions to give 2 breaths, blood flow also stops, and this cessation of blood flow leads to a quick drop in the blood pressure that had been built up during the previous set of compressions.[36] Indications CPR should be performed immediately on any person who has become unconscious and is found to be pulseless. Assessment of cardiac electrical activity via rapid rhythm strip recording can provide a more detailed analysis of the type of cardiac arrest, as well as indicate additional treatment options. Loss of effective cardiac activity is generally due to the spontaneous initiation of a nonperfusing arrhythmia, sometimes referred to as a malignant arrhythmia. The most common nonperfusing arrhythmias include the following: VF Pulseless VT PEA Asystole Pulseless bradycardia

Although prompt defibrillation has been shown to improve survival for VF and pulseless VT rhythms,[37] CPR should be started before the rhythm is identified and should be continued while the defibrillator is being applied and charged. Additionally, CPR should be resumed immediately after a defibrillatory shock until a pulsatile state is established. This is supported by studies showing that preshock pauses in CPR result in lower rates of defibrillation success and patient recovery.[32] In a study involving out-of-hospital cardiac arrests in Seattle, 84% of patients regained a pulse when defibrillated during VF.[30] Defibrillation is generally most effective the faster it is deployed. Contraindications The only absolute contraindication to CPR is a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order or other advanced directive indicating a persons desire to not be resuscitated in the event of cardiac arrest. A relative contraindication to performing CPR may arise if a clinician justifiably feels that the intervention would be medically futile, although this is clearly a complex issue that is an active area of research.[38, 39]

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support Quick Study Guide 2015 Updated GuidelinesVon EverandAdvanced Cardiac Life Support Quick Study Guide 2015 Updated GuidelinesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (6)

- Lectii ScoalaDokument43 SeitenLectii ScoalaGaudiMateiNoch keine Bewertungen

- IntroductionDokument4 SeitenIntroductiondyah ayuNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPR & Electrical TherapiesDokument67 SeitenCPR & Electrical TherapiesRizaldy Yoga67% (3)

- CPCRDokument36 SeitenCPCRapi-19916399100% (1)

- UntitledDokument11 SeitenUntitledAnkita BramheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation 2015Dokument31 SeitenCardiopulmonary Resuscitation 2015Clarissa Maya TjahjosarwonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mona Adel, MD, Macc A.Professor of Cardiology Cardiology Consultant Elite Medical CenterDokument34 SeitenMona Adel, MD, Macc A.Professor of Cardiology Cardiology Consultant Elite Medical CenterOnon EssayedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physiology of Closed Chest CompressionsDokument3 SeitenPhysiology of Closed Chest CompressionsAriniDwiLestariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument3 SeitenCardiopulmonary ResuscitationLee Liang Lee LiangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Life SupportDokument10 SeitenBasic Life SupportAlvin M AlcaynoNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is BLS?: Respiratory ArrestDokument2 SeitenWhat Is BLS?: Respiratory ArrestStephanie Joy EscalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument1 SeiteCardiopulmonary ResuscitationJoushwa Paul duraiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardioplumonary RDokument40 SeitenCardioplumonary RABREHAM BUKULONoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Life Support (BLS) : Prepared by DR Melaku M (ECCM R-1) Moderator:dr Yonas (Assistant Professor of ECCM)Dokument42 SeitenBasic Life Support (BLS) : Prepared by DR Melaku M (ECCM R-1) Moderator:dr Yonas (Assistant Professor of ECCM)Balemlay HailuNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLSDokument61 SeitenACLSmgthida935100% (1)

- Cardiopulmonar Y ResuscitationDokument34 SeitenCardiopulmonar Y ResuscitationRatuSitiKhadijahSarahNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLS Provider Manual 2015 NotesDokument5 SeitenACLS Provider Manual 2015 Notescrystalshe93% (14)

- Cardio Pulmonary R Ry Resuscitation 2010Dokument26 SeitenCardio Pulmonary R Ry Resuscitation 2010Fatahillah NazarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Cardiac Life Support 2011Dokument6 SeitenBasic Cardiac Life Support 2011Tashfeen Bin NazeerNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2009 UCSD Medical Center Advanced Resuscitation Training ManualDokument19 Seiten2009 UCSD Medical Center Advanced Resuscitation Training Manualernest_lohNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation: Internal and Critical Care Medicine Study NotesDokument18 SeitenCardio Pulmonary Resuscitation: Internal and Critical Care Medicine Study NoteseryxspNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardio Pulmonary Resuscitation 2010: Djayanti SariDokument26 SeitenCardio Pulmonary Resuscitation 2010: Djayanti SariAlessandro AlfieriNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLSDokument39 SeitenACLSJason LiandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument20 SeitenCardiopulmonary ResuscitationDrmirfat AlkashifNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines - In-Hospital ResuscitationDokument18 SeitenGuidelines - In-Hospital ResuscitationparuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportDokument35 SeitenGuidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportindahNoch keine Bewertungen

- DoccDokument6 SeitenDoccNithiya NadesanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Life Support-RESSU CouncilDokument30 SeitenAdvanced Life Support-RESSU CouncilGigel DumitruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive Summary VF20101018Dokument24 SeitenExecutive Summary VF20101018Dana SoimuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Life Support: BY Himanshu Rathore M.Sc. Nursing 1 YearDokument30 SeitenBasic Life Support: BY Himanshu Rathore M.Sc. Nursing 1 YearHimanshu RathoreNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument10 SeitenCardiopulmonary ResuscitationLilay MakulayNoch keine Bewertungen

- CPR 2014 SeminarDokument43 SeitenCPR 2014 SeminarMinale MenberuNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAB-CPR UpdateDokument15 SeitenCAB-CPR Updatedragon66Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonery ArrestDokument8 SeitenCardiopulmonery Arrestt9d2014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Informe Del Taller de RCPDokument6 SeitenInforme Del Taller de RCPDuke 24Noch keine Bewertungen

- CPR LectureDokument9 SeitenCPR LecturejacnpoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS)Dokument27 SeitenAdvanced Cardiovascular Life Support (ACLS)Sara Ali100% (4)

- Acls Course HandoutsDokument8 SeitenAcls Course HandoutsRoxas CedrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acls 2015Dokument13 SeitenAcls 2015I Gede Aditya100% (5)

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support: Valentina, MD, FIHADokument34 SeitenAdvanced Cardiac Life Support: Valentina, MD, FIHAfaradibaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiac ArrestDokument30 SeitenCardiac ArrestagnescheruseryNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLSDokument78 SeitenACLSKajalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportDokument34 SeitenGuidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportParvathy R NairNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Life SupportDokument4 SeitenBasic Life Supportraven_claw25Noch keine Bewertungen

- DEFIBrilatorDokument43 SeitenDEFIBrilatoranon_632568468Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument16 SeitenCardiopulmonary Resuscitationsswweettii23Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civic Welfare Training ServiceDokument13 SeitenCivic Welfare Training ServiceVanessa Rose RofloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Presented By:-Swapnil WanjariDokument41 SeitenCardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Presented By:-Swapnil WanjariSWAPNIL WANJARINoch keine Bewertungen

- Nelec2 Week 17Dokument13 SeitenNelec2 Week 17Michelle MallareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Referensi 7Dokument8 SeitenReferensi 7Nophy NapitupuluNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLS II Sept 25 StudentsDokument60 SeitenACLS II Sept 25 StudentsLex CatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Adult Advanced Life Support: Resuscitation Council (UK)Dokument23 SeitenAdult Advanced Life Support: Resuscitation Council (UK)Masuma SarkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acls Seminar MeDokument62 SeitenAcls Seminar MeAbnet Wondimu100% (1)

- Anzcor Guideline 11 10 1 Als Traumatic Arrest 27apr16Dokument11 SeitenAnzcor Guideline 11 10 1 Als Traumatic Arrest 27apr16Mario Colville SolarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal CPRDokument5 SeitenJurnal CPRSukuria UsmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric Advanced Life Support Quick Study Guide 2015 Updated GuidelinesVon EverandPediatric Advanced Life Support Quick Study Guide 2015 Updated GuidelinesBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- Basic Life Support (BLS) Provider HandbookVon EverandBasic Life Support (BLS) Provider HandbookBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (2)

- MacBook Pro (14-Inch, 2023) - Geekbench 2Dokument1 SeiteMacBook Pro (14-Inch, 2023) - Geekbench 2daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Wrist Joint Anatomy-1Dokument5 SeitenWrist Joint Anatomy-1daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 21Dokument8 SeitenChapter 21daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Glycolysis and Citric Acid Cycle: Hexose KinaseDokument1 SeiteGlycolysis and Citric Acid Cycle: Hexose Kinasedaniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tympanic Membrane PerforationDokument10 SeitenTympanic Membrane Perforationdaniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- List of The Students For Participation in Health Mela: Fashion Show (Male) Fashion Show (Female)Dokument2 SeitenList of The Students For Participation in Health Mela: Fashion Show (Male) Fashion Show (Female)daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revised Lesson Plan For Nursing Research Class - Project 2Dokument4 SeitenRevised Lesson Plan For Nursing Research Class - Project 2daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- National HealthDokument5 SeitenNational Healthdaniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rotation Plan: Iv Year B.SC NursingDokument1 SeiteRotation Plan: Iv Year B.SC Nursingdaniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pott Spine PDFDokument7 SeitenPott Spine PDFdaniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Abdominal Hysterectomy: MS (Refer To Hysterectomy)Dokument1 SeiteAbdominal Hysterectomy: MS (Refer To Hysterectomy)daniphilip777Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Needs of Critically Ill ChildDokument9 SeitenNutritional Needs of Critically Ill Childdaniphilip777100% (11)

- JOMON - RESUME - ICU Up Dated 26-2-11Dokument4 SeitenJOMON - RESUME - ICU Up Dated 26-2-11Aadesh MaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shaun's Guide To Basic NRP: Equipment CheckDokument7 SeitenShaun's Guide To Basic NRP: Equipment CheckLori BeckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grade 9 Health Quarter 3Dokument18 SeitenGrade 9 Health Quarter 3spine clubNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post TestDokument11 SeitenPost TestDemuel Dee L. BertoNoch keine Bewertungen

- ATLSDokument18 SeitenATLSإكرام النايبNoch keine Bewertungen

- RapidSOS Outcomes White Paper - 2015 4Dokument30 SeitenRapidSOS Outcomes White Paper - 2015 4rmateo_caniyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Emergency - Medicine.ebook EEnDokument644 SeitenEmergency - Medicine.ebook EEnAlina GeorgianaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Muriatic Acid MsdsDokument6 SeitenMuriatic Acid MsdsChe Gu BadriNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACLS Algorithms SlideDokument26 SeitenACLS Algorithms SlidehrsoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1354 Athlete Cardiac Arrests, Serious Issues, 922 of Them Dead, Since COVID Injection - Real ScienceDokument205 Seiten1354 Athlete Cardiac Arrests, Serious Issues, 922 of Them Dead, Since COVID Injection - Real ScienceHansley Templeton CookNoch keine Bewertungen

- In Hospital PDFDokument6 SeitenIn Hospital PDFCarmen Garcia OliverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neonatal ResuscitationDokument7 SeitenNeonatal ResuscitationmilindNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Basic Life SupportDokument20 SeitenIntroduction To Basic Life SupportJyle Mareinette ManiagoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RJPDokument72 SeitenRJPFembriya Tenny UtamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACR Sample OntarioDokument5 SeitenACR Sample OntarioAlisha PowerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lasers in SurgeryDokument22 SeitenLasers in Surgerynuclearbrain11Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pulmonary Hypertension and Covid19Dokument17 SeitenPulmonary Hypertension and Covid19Shahdan Taufik IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Red Cross Training Content MapDokument2 SeitenRed Cross Training Content MapHoward SeibertNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesia For Obstetrics and Gynecology and Regional AnesthesiaDokument16 SeitenAnesthesia For Obstetrics and Gynecology and Regional AnesthesiaWiny ReginaNoch keine Bewertungen

- NCM118 Refelctive QuestionsDokument3 SeitenNCM118 Refelctive QuestionsingridNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidance On The Use of Personal Protective Equipment Ppe in Hospitals During The Covid 19 OutbreakDokument9 SeitenGuidance On The Use of Personal Protective Equipment Ppe in Hospitals During The Covid 19 OutbreakGerlan Madrid MingoNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Aid Part 2Dokument34 SeitenFirst Aid Part 2teachkhimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pediatric ResuscitationDokument55 SeitenPediatric ResuscitationMargaretDeniseDelRosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cop-5 Do Not Resuscitate-DnrDokument3 SeitenCop-5 Do Not Resuscitate-DnranithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bls QuestionDokument7 SeitenBls Questionmonir61100% (2)

- Quality CPR Training (QCaT) DeviceDokument16 SeitenQuality CPR Training (QCaT) DeviceSundresan PerumalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practise 2Dokument16 SeitenPractise 2Mohammad Fariz100% (6)

- ABC Versus CAB For Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDokument16 SeitenABC Versus CAB For Cardiopulmonary Resuscitationaldo199Noch keine Bewertungen

- APGAR Score and Ballard Score: K. C. JanakDokument41 SeitenAPGAR Score and Ballard Score: K. C. JanakJanak Kc50% (2)

- Basic Life Support (BLS)Dokument110 SeitenBasic Life Support (BLS)daveNoch keine Bewertungen