Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

"Lazarescu, Come Forth!": Cristi Puiu and The Miracle of Romanian Cinema

Hochgeladen von

Cristiana TataruOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

"Lazarescu, Come Forth!": Cristi Puiu and The Miracle of Romanian Cinema

Hochgeladen von

Cristiana TataruCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

"Lazarescu, come forth!

":

Cristi Puiu and the Miracle of

Romanian Cinema

Jeanine Teodorescu and Anca Munteanu

Lasciate ogni speranza, voi ch 'ntrate!

(Abandon, all hope ye who enter)

-Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, "The Infemo"

A la fin du spectacle tu vas mourir

(At the end of the performance you are going to die)

-Eugne Ionesco, Le roi se meurt (Exit the King)

Cristi Puiu's The Death of Mr. Lazarescu received Un certain

regard at Cannes (2005), The Silver Orb Award (Alba Regia 2005),

The Golden Tower (Palie 2005), The Grand Prix of the Jury at the

Intemational Copenhagen Film Festival (2005), Bayard d'Or for

best film and best actress (Namur 2005), The London Critics Circle

Film Award (Foreign Language Film of the Year, 2006), The Chicago

Intemational Film Festival Silver Hugo Special Jury Prize (2006),

World Cinema Award, offered by BBC Four (2007). This impressive

record is not singular; many of the directors belonging to the Romanian

New Wave' have produced-often on low budget (Puiu's film cost a

mere 350,000 Euros) and in the absence of adequate infrastructure

in the sequence of production, circulation and presentation-award-

winning feature films that have impressed critics worldwide and that

have been considered one of the most stimulating and promising

developments in recent years in Eastem European national cinemas.^

According to Puiu, The Death of Mr Lazarescu^ is part of a

projected series entitled "Six Stories from the Outskirts of Bucharest,"

inspired by Eric Rohmer's Six contes moraux (Six Moral Tales). They

51

are conceived as love storiesthe love between a man and a woman,

love for one's children, love of success, love between friends, and

carnal love. The Death of Mr Lzrescu, the first film of the series,

is predicated on the ancient Biblical command "Love thy neighbor as

thyself, , which is derived from the Hebrew verses: "But the stranger

that dwelleth with you shall be unto you as one bom among you,

and thou shalt love him as thyself; for ye were strangers in the land

of Egypt" (Leviticus 19:34) and continues to be an essential feature

of Christianity. Puiu plays splendidly with the complexities of this

commandment, which establishes the proper relation of human beings

to one another, modeled on the relation of human beings to God. The

very logic of this directive suggests that the love we should have for

our neighbors is identical to the love God has for uscomplete and

perfect. Love for God equals love for humankind. But the ethos of

neighborly love is certainly intricate and difficult in the story. This

meticulous problematization is one of the virtues of Puiu's film and,

as this essay argues, its force comes primarily from the exceptional

mastery of the film's mise-en-scne.

The Death of Mr Lzrescu is the story of a 62-year-old retired

engineer, Dante Remus Lzrescu (Ion Fiscuteanu), who lives with

his three cats in a shabby, dirty apartment in Bucharest. On Saturday

morning he wakes up with an unusually severe headache and acute

stomach pain; in the evening, after hours of useless self-medication,

he calls for an ambulance. While waiting for its arrival, Lzrescu

drinks Mastropol, a strong homemade alcoholic drink, and calls his

sister, who lives with her husband in Trgu-Mure, a Transylvanian

city relatively far from Bucharest. When it becomes evident that the

ambulance is not coming, Lzrescu calls again and then asks for his

neighbors' assistance. They give him some pills for nausea, help him

back to his apartment, and lay him down on his bed.

Gradually his condition worsens, and soon he vomits blood.

The ambulance finally arrives and Mioara (Luminija Gheorghiu), the

paramedic, performs an examination while inquiring into Lzrescu's

medical history. He had had ulcer surgery more than ten years before

and suffers from varicose veins on both legs. Suspecting colon cancer,

a more serious condition than Lzrescu is prepared to accept, Mioara

decides to take him to the emergency room. Before leaving for the

hospital, she calls Lzrescu's sister and advises that she come and

visit her brother as soon as possible. They set out for the emergency

52

room, but because of a massive traffic accident which had taken place

just hours before, three hospitals, overcrowded with the injured,

refuse to accept him. When Mr. Lzrescu finally arrives at the fourth

hospital, it is probably too late. Two nurses scrupulously prepare him

for the surgical procedure, but there is no indication-the ending is

rather ambiguous-that Lzrescu will even make it to the surgery

room. In fact. Valerian Sava interprets the black screen after the cut of

the film's last shot as an ellipsis, not as the death of Lzrescu ;?er se.

In his view, the ritual of bathing before surgery parallels the bathing of

the corpse before the fiineral.

There is no question that the film, which has the traumatizing

characteristics of a nightmare, puts the viewer in a state of strange

and intense anguish. And yet, Puiu reduces the intensity of this almost

unbearable feeling by presenting a multitude of facts, interesting

people, and discrete events. First, we have Lzrescu's three neighbors-

-Sandu (Doru Ana) and Mihaela Sterian (Dana Dogaru), the couple

living across the hallway from Lzrescu's apartment, and Gelu, a

young man who lives upstairs with his family. None of these three

characters, despite their apparent concem, really pays much attention

to the sick man; they actually focus on Lzrescu only at those times

when they are criticizing him or joking about his heavy drinking (thus

anticipating some doctors' reactions later in the movie) or when they

censure him for his negligence and his filthy apartment. Otherwise,

they remain completely absorbed in their own trivial preoccupations

the cooking of quince jelly, the return of a drill that Gelu had borrowed

from Sandu, and their plans for a trip to a wine producer in Focani,

an area famous for its vineyards, and so onas if Lzrescu were just

an unpleasant, annoying interruption in their normal lives over the

weekend.

The neighbors' casual chatting, which takes place almost

exclusively around or over Lzrescu's head, juxtaposed with his

quiet, unnoticed slipping away from the world represents one ofthe

most brilliantly choreographed passages in Puiu's film. These scenes

are disturbing and funny at the same time, the characters sometimes

eliciting our censure or disapproval, but the action overall remains

profoundly touching. Such moments include Sandu's conversation

with his younger neighbor which, ironically, reveals that the wine

Lzrescu imbibes and for which he is either teased or chastised is,

in fact, acquired, at a price, through the very neighbors who mock

53

him. Equally ironic is the discussion in the building's hallway (where

the light flickers on and off) about various incongruous remedies that

Sandu and Mihaela offer Lzrescu at random. Probably the funniest

moment of this segment is generated by Mihaela's strange idea to offer

Lzrescu a plate of homemade pork moussaka, an unusually rich and

indigestible dish, only moments after Lzrescu has vomited blood.

All these details exhibit Mihaela's and her husband's shocking

ignorance and lack of minimal common sense (for example, they

suggest and offer to Lzrescu various types of medications that they

have in the house). Remarkable comic characters (echoing Ionesco's

absurdest humor), present features that will resurface in many of

the film's scenes, especially in the portrayal of doctors and nurses

from several hospitals. The foolish pair, Mihaela and Sandu, who

continually insult one another or argue with each other and who, out

of ignorance combined with a know-it-all attitude, could have easily

killed Lzrescu themselves, show certain, albeit feeble, signs of

compassion and kindness. Sandu, for instance, would probably have

accompanied Lzrescu to the hospital (as the paramedic recommends)

if it were not for his wife; Mihaela in turn, despite her selfishness

and discourtesy, cleans the slippers and the carpet on which the old

man has vomited. In any case, Puiu's technique does not allow for the

viewer's distancing himself too much from these two characters. They

may remind us of ourselves in our less-than-entirely-noble moments.

Nonetheless, what happens in the film's second part is tragically and

inescapably connected to Sandu's (conscious or unconscious) failure

to heed Lzrescu's call for help after he has fallen in the bathtub and

seriously hurt his head.

The second part of the film narrates Lzrescu's Kafkaesque

journey through the dreadful circles of the Romanian medical Inferno

and, simultaneously, his progressive loss of independence, force,

mobility, command of language, control of bowels, and even clothes.

Between Saturday night and early Sunday moming, Mioara and the

ambulance's driver, Leo (Gabriel Spahiu) cart Lzrescu to four

hospitals. At St. Spiridon Hospital, Lzrescu's first stop, the medical

personnel orbit obediently about a middle-aged doctor who patronizes

and infantilizes his patients, insults Lzrescu for his drinking, and

reprimands Mioara for bringing him into the emergency room. Granted

that he has to deal with a multitude of patients at the same time, this

short-tempered and vain character fails to perform adequately. In

54

the end, his diagnosis comes as "You are fine! Just stop drinking."

At the University Hospital, Lzrescu's second stop, the neurologist,

the ER doctor, and the radiologist act properly but in a distressingly

impersonal manner, absorbed as they are in playful flirtations and

repartee among themselves. The neurologist's colleague. Dr. Breslau,

displays such cynicism (perhaps his only armor against the stresses

of his profession) that even his remarkable sense of humor becomes

difficult, if not impossible, to handle for some spectators.

At Filaret Hospital, the two young doctors who examine

Lzrescu are particularly ruthless and offensive, treating Mioara not

as a colleague but as a person of inferior professional status who needs

to be reminded, repeatedly, how insignificant she is. It is precisely this

unprofessional conduct and unrestrained self-importance that increase

the viewer's anger when confronted with the doctors' ridiculous

attempts to have Lzrescu, almost totally incapacitated at this point,

fill out forms, sign consents before surgery, and answer questions

that he does not understand. If the earlier doctors are arrogant and

ultimately ineffectual, these two doctors are purely inhumane. They

display a false and unbecoming sense of superiority that divides the

world into "us"-young, healthy, strong, important, and competent,-

-and "them"-old, sick, weak, poor, and insignificant. In fact, the

patient's incapacity to make a decision tums into a pretext for them

not to perform their duties.

The final stop is the Bagdasar Hospital, where Lzrescu is

finally admitted. It is a mysterious place, dimly lit and almost deserted.

Interestingly, the nurses and doctors are all women with soft voices

and delicate and efficient gestures. Again, Puiu cleverly moves the

emphasis from the institution and the abstract to the individual and

the particular. Cranky, sarcastic, unpleasant, and generally isolated

in his miserable loneliness, at the beginning of the film Lzrescu

nevertheless had an identity, a history, habits, animals that he loved

and protected, and, no matter how estranged or alienated, a family. At

the end ofthe film, this individual is reduced to a piece of flesh on an

infirmary bed in a cold hospital.

ft is difficult to repress one's anger and frustration with these

presumptuous and detached doctors. Even those who seem to listen

to Lzrescu more attentively and who do not insult or patronize him

(most of them call him "pops") are trapped in this cycle of indifference

that inevitably victimizes the patients in both blatant and insidious

55

ways. Generally, the doctors' language is designed to infantilize

Lazarescu or make him feel guilty, to humiliate or embarrass him. It

seems that the institution (hospital, emergency rooms, medical staff)

is there mainly for the doctors and not for the suffering patients. Like

Arthur, one of Frederick Wiseman's characters in his documentary

Titicut Follies, about the appalling conditions at an asylum for the

criminally insane, Lazarescu might very well say, "the place is doing

me harm."

However, the image of the Romanian health-care

establishment is not uniformly dark. Following the same formula that

he used in Sandu's and Mihaela's portraits, Puiu presents the doctors

and nurses from these four hospitals with a mixture of brutal honesty

and compassion. They are vivid and complex characters; many are

portrayed in a negative light, but there are some whose humanity

is evident. At the Trauma Center, the tall insufferable doctor who

condemns Lazarescu for drinking by calling him "a pig" and who also

repeatedly insults Mioara, eventually writes an order for a CAT scan

at another hospital. Dr. Drago Popescu, the neurologist, has patience

and understanding (his name is the shortened form of Dragomir,

which means "precious peace"). Under extreme duress in the ER at

the University Hospital (ten to twenty seriously injured people had

just been brought in after the truck accident). Dr. Popescu calls another

doctor and asks him to help his patient by conducting an immediate

brain and liver tomography. When told that it is impossible because

of the overwhelming situation. Dr. Popescu replies, "Would you have

done it if I had told you that this was my mother-in-law?" Lazarescu is

finally accepted by Dr. Breslau, who is in charge of the tomographer,

and has a mordantly clever sense of humor; he asks his assistant to

prepare the patient for "launching" (being put inside the tomographer),

after telling her that Mr. Lazarescu will have two photos taken "of the

pt and the attic" (the liver and the brain). It is this scan which reveals

a blood clot in his brain and a problem with his liver that "nobody,"

Breslau observes, "can do anything about." He is also a good-hearted

human being; after he discovers the seriousness of Lzrescu's state

of health-"These neoplasms are Discovery Channel stuffBreslau

calls in the surgeons' unit; unfortunately, nothing can be done under

the circumstances: the life and death cases caused by the accident have

precedence.

To create even more ambiguity in the depiction of the medical

56

personnel, Puiu not only suggests that long hours and a persistently

stressful environment bleed compassion out of doctors-a realistic and

credible argument-but also presents Lzrescu himself as a difficult

and, according to Leo, the ambulance driver, a rather irresponsible

patient. As short-tempered and vain as are some of the doctors he

encounters along his joumey from one hospital to another, Lzrescu,

stubbom and irascible, annoys almost everybody, including Mioara,

who repeatedly asks him to keep his mouth shut. The film's first

segment, which contains the scenes preceding the nightmarish

ambulance ride, functions as a biographical prologue to Dante

Lzrescu's descent into the infemal territory of his final hours and

provides the viewer with details about his life through various scenes

and short but revealing conversations. His wife had died of cancer

eight years earlier, and his only daughter, Bianca, lives in, Canada.

Lzrescu has a younger sister, Eva, who is married to a man named

Virgil. This couple has no children, but Bianca seems to be rather close

to them since, in his phone conversation with his sister, Lzrescu

complains that his daughter calls them more often than she calls him.

His phone conversation with Eva and Virgil, in particular, reveals

an intractable and impetuous character who defends his excessive

drinking and insists that as long as he pays for his alcohol he should

be left alone. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that the only possible

answer to the frequently repeated question asked by doctors and

nurses, in various hospitals, "Who is accompanying him?" is that, in

fact, there is no close relative or friend there with him. And yet, even

this answer, which time and again would appear to define Lzrescu's

distressing condition, is made ambiguous by Puiu's and Rdulescu's

intentionally unsententious script. Despite his own desire "to be left

alone," he finds in Mioara the mysterious presence of a very Good

Samaritan.

However, even the endlessly tolerant Mioara, the most

touching character in the film, has an inexplicable moment of

unkindness, when she ignores Lzrescu's frantic request for some

water. Otherwise, although herself in pain (she has gall-bladder

problems), Mioara proves to be a true guardian angel to Lzrescu.

At first, Mioara wants someone to take Lzrescu off her hands, but

her attempt to convince Sandu or Mihaela to accompany Lzrescu to

the ER fails and, consequently, she is forced to remain with him until

the end. In the ambulance, she talks to him out of common courtesy

57

and perhaps compassion. But the more the doctors try to dispose of

Lzrescu, the more emotionally involved with him she becomes,

claiming the case as her own. In fact, all the hospital workers tend

to see Lzrescu as her problem. In each hospital, she tries hard to

advocate for his cause in order to convince the doctors to take care of

the patient she has brought in and to advocate for his cause. She tries

to comfort him until the very end, even after six or seven hours spent

on the way from one hospital to another. In the neurological section

ofthe hospital, where the two young doctors reach the highest level of

callousness and arrogance, Mioara's courage and defiance are simply

heroic. In that place, where human life is held cheap and betrayed,

she restores a sense of dignity and basic human decency. Through her,

Puiu moves forward one ofthe film's main themes: the individual's

effort to preserve his or her humanity and dignity while struggling

against arbitrary laws and dehumanizing bureaucratic systems.

Complex human events such as Lzrescu's conversation

with his sister, the phone conversation with the emergency services,

his interactions with his neighbors, Mioara, and the doctors are not

evoked stenographically, in a conventional fragmented fashion, but

explored in what we imagine to be their "real" duration. Following

the film's rather intriguing first frame-the image, in the darkness of

the night, of a soulless, Soviet-style apartment building with several

lit windows-the camera enters Lzrescu's apartment, tracking his

movements from one room to another, from his apartment to his

neighbors' door, then back into his apartment where the encounter

with Mioara, the nurse, will take place, and finally out of his apartment

and into the ambulance.

The moderately slow motion ofthe camera allows us to see at

great length the filthy kitchen table, the dirty dishes clustered by the

sink, the rusted strainer hanging on the wall, the dusty newspapers

scattered on shelves, on the table in the living room, and on chairs,

and the soiled sheets covering his sofa and the armchair. The shot of

the drab outside (the street and the building), followed by the essential

squalor of the apartment in the next shot, prepare the portrayal of Puiu's

anti-hero, in a style similar to Balzac's descriptions in his novels,

which start with detailed depictions of the city, the street, and the

house, and then proceed to the rooms as reflections ofthe character's

personality. Similarly, most ofthe film, although documentary-like,

forces us to participate in the whole experience. This has to do with

tempo, rhythm, movement, the image of paramedics pushing the

58

stretcher towards the camera in a back traveling shot. The remarkable

result of this technique is that one almost/ee/s oneself inside the film.

Puiu's use of such strategies activates the viewer's emotional and

rational faculties in complete synchronization with the script and the

mise-en-scne. This is part of a shooting philosophy which, instead

of anticipating what is going to happen, attempts to capture, rather

intensely, the drama that is unfolding. In short, Puiu does not impose

an aesthetic, but allows the material to reveal itself This delicately

choreographed dialogue between the camera and the viewers creates

a sense of immediateness, of raw material delivered in a documentary

style.

There is nothing particularly didactic about this sequence of

scenes; images live entirely in the moment, simply showing reality,

generating no manufactured conflicts and raising no platforms for

sermons. What seems to interest Puiu is the authenticity of his images,

their power to impress the audience and force them to live with this

smelly old dmnk in his bleak world. More importantly, the most

forceful, indeed visceral, images undoubtedly disturb the viewers'

sense of voyeuristic detachment, of emotional equilibrium and,

hence, of complacency. Consequently, compared to traditional films,

where directors use cinematic elements to persuade viewers through

provoked emotions, Puiu's film leaves the viewers in a state of general

intellectual angst.

Close-ups are an important element, particularly in the film's

first segment, which explores how a certain individual copes with

loneliness, suffering-physical and emotional-and abandonment.

Lzrescu is introduced almost immediately, in the film's second frame;

we see an aging man, unshaved, wearing a grey knit cap and a striped

polo shirt, living alone with his three cats. He is completely indifferent

to his repulsive surroundings and focuses all his attention on his cats.

The tension between the desolation surrounding this old man and the

affection his voice radiates when he talks to his cats is intensified by

the tight, almost-too-intense close-ups. The shot composition of this

segment is completely controlled by the physicality of Lzrescu's

movements and gestures. The interior of his apartment functions as an

emotional correlative to Lzrescu's character and circumstances. The

close-ups, the choice of objects and actions (the disheveled apartment,

Lzrescu's constant drinking, and the tense phone conversation with

his family), are perfectly calibrated by Oleg Mutu's cinematography.

59

Lzrescu's entire drama is told without theatrical or melodramatic

elements, extravagant lighting, or affected acting.

The film's diegetic world supports the mood of documentary

realism and the cinma vrit approach. Traditionally associated

with hand-held camera filming, the use of unstable and jerky images

indicates Puiu's admiration for auteur films and for a cinematic look

as far away as possible from commercial movies. There are Godardian

influences such as the scene where Lzrescu and his neighbor, Sandu,

hear an announcement on TV about the tragic events that will later

play an essential role in the protagonist's own tragedy. This second

embedded discourse ofthe television set recalls the Deleuzian principle

of the "crystal image". Deleuze describes "the crystal image" as an

exchange enacted between the actual and the virtual and explains how

modern cinema has managed to abandon such devices as flashbacks

and slow motion, for example, in favor of an increasingly ambiguous

relationship between these two categories. The crystal image involves

a multifaceted, mysterious record of juxtaposed realities. In Puiu's

movie, this juxtaposition creates a touching exploration of possibility,

choice, and fate. Also, like Wiseman, Puiu utilizes the mode of indirect

address-the viewer is not acknowledged by the film, characters do not

look at the camera nor speak directly to us. His film involves a faith

in apparently un-manipulated reality, a refusal to tamper with life as

it presents itself, similar to Andre Bazin's early project of allowing

reality to speak for itself.^ But, of course, there is manipulation in his

brilliant editing and his choice of camera angles. Puiu's vision owes

more to international (French New Wave and Italian Neorealism)

than to Romanian artistic influences; however, Puiu's cinematic

minimalism and his persistent use of long shots and lateral framing

can be compared to the techniques used by another Romanian director,

Lucian Pintilie. *

The Death of Mr Lzrescu emphasizes the story-telling,

not philosophical ideas or abstract principles principles: these are the

events that took place at the end of the life of a particular, lonely,

sulering man. Puiu's position here resonates with documentarist John

Grierson's conviction that "the ordinary affairs of people's lives are

more dramatic and more vital than all the false excitement you can

muster" (225). It is true, however, and this is undoubtedly one of

Puiu's most remarkable achievements, that every detail, every gesture,

every conversation contains certain marks of recent social and political

60

history (see, for instance, Lzrescu's shabby apartment building, a

sad relic of the communist era and Soviet influence), although there

is no overt social or political commentary in these depressing images

and although they do not necessarily describe the situation ofa country

that only recently emerged from the darkest night of totalitarianism. In

this respect, Puiu's grim images resemble Italian Neorealism, with its

devastated streets and miserable people. But it would be too easy to

conclude that the film should be interpreted merely as a condemnation

or a satire of the Romanian medical establishment or that the film's

anti-institutional bias constitutes Puiu's main concem. Puiu, like

Lucian Pintilie, is not primarily interested in social or political critique,

although this critique is implicitly understood. Pintilie declares in an

interview:

What I want to talk about in my films, is our ineluctable

and difficult advancement towards death, a joumey

periodically lightened up by the spark of comic

revelry...It is not my responsibility to expose and

fight evil (this is the church's role). As an artist, I am

endlessly fascinated by the extraordinary multiplicity

of the monstrous, the great comic contrasts. I am

purely obsessed with the monster's unique artistry. I

do not fight it, I simply describe it. (our translation)'

The Death of Mr. Lazarescu seems to convey a similar position. The

spectators, who witness Lzrescu's frightful journey, its somber and

even its funny moments, its profound and trivial dimension, recognize

their own ineluctable advancement towards death and in so doing feel

a sense of solidarity and perhaps empathy for this man whose life ends

silently in front of their eyes. Puiu's movie is, after all, a film about

loveor lack of love for our fellow human beings and less about

institutions or the afflictions of our time.

All three names of the protagonist, Dante Remus Lazarescu,

are important elements of the film; all are symbolic and operate under

the sign of death. Dante recalls the Divine Comedy and the narrator's

joumey through the Infemo under the guidance of Virgil. Interestingly,

there are two Virgils in the film: one is Lzrescu's brother-in-law,

with whom he speaks on the phone, and the second is the stretcher-

bearer who, at the end of the film, is called by a nurse to come and

take him to Dr. Anghel (Dr. Angel) for the surgery. Hence, Virgil is

handing Dante to the Angel. Hell will soon become a thing of the

past. Remus, one of the two mythical founders of Rome, was slain by

61

his brother for having trespassed the borderline drawn by Romulus.

Lzrescu is also at a borderline, that between life and death, which, in

the end, he will have to cross or trespass. Film critic Dominique Nasta

suggests that all three names are meant to "set up a double discourse

oscillating between the unbearable reality of pain and suffering and a

sustained ironic mode." This could be true when we recall that some

doctors remark on the gravity of Lzrescu's first name, Dante, while

all his neighbors address him with Romic, a humorous derivation

of Remus that demythologizes, cheapens, and renders ridiculous the

ancient name.

Lzrescu undoubtedly refers to the resurrection of Lazarus

from the Gospel, and to Jesus's famous words, "Lazarus, come forth!"

The dead man came out of his tomb, his hands and feet bound with

strips of cloth. Jesus said to those in attendance, "unbind him and let

him go" (John 11:1-45). Mr. Lzrescu's feet are also bandaged, and

Mioara, the paramedic, draws the nurses' attention to his bandages,

asking them to be careful. Lzrescu's harrowing joumey through

Hell places him on the threshold of another realm, over which he is to

be guided by an angel (Dr. Anghel). This is a kind of resurrection, after

all, resembling not only that of the Biblical Lazarus but also that of

Jesus himself. But there is another story of another Lazarus: Lazarus

the poor man, who was covered with sores and very hungry, and who

was not helped by the rich man (Luke 16:19-31). He was, however,

comforted after his death and received into Abraham's bosom, while

the rich man was taken to Hell. The rich man is not accused of being

rich, but of being neglectful of the poor people around him. This story

may also apply to some of the doctors and their indifference to their

neighbors-that is, their patients.

Undoubtedly, The Death of Mr Lzrescu, with its unique

blend of empathy and indictment, shot in the fly-on-the-wall

documentary style but rich in poetic subtexts, offers an emotionally

controlled portraiture of a suffering individual confronted with vast,

impersonal social forces and ultimately crushed by a bureaucratic

system that makes adequate medical care difficult, and, in certain

situations, impossible. But even this grave, most serious theme

becomes in Puiu's film an opportunity for black comedy* as the

doctors' inefficiency is mordantly revealed by Lzrescu's gradual

helplessness, by his loss of mental and physical ability and command

of language. Most importantly, however, this film is not only about

62

death and institutionalized inhumanity but also about life and human

solidarity. While for the viewer the hospital experience has an

unnerving effect, Mioara's bond with Lzrescu--a man whose profile

is both disturbing (Lzrescu is unwell before being physically sick)

and sympathetic (his love for animals)-signifies a renewed assurance

conceming human dignity and saves the film from nihilism. Mioara

performs an ambiguous role: on the one hand, she is Lzrescu's

much needed companion and guide through his Dantesque trials; on

the other, she is the agent of change and transition who sees her charge

to the end of the joumey. Beatrice-1 ike, she inaugurates another rite

of passage, by handing Lzrescu over to the Angel. While guiding

her patient and bringing Lzrescu to the end of his joumey, Mioara

develops a strange relationship of friendship with him. Interestingly

enough, like Kieslowski's Red, Puiu's film also becomes a metaphor

for love, where two human beings, a nurse and a patient, are brought

together by chance and bond, "delicately developing a network of

dependencies" (Coates 153) at the frontier between life and death.

The film presents a reflection on agape (love as a model

for humanity, Christian love) and thanatos (death). Through this

meditation on the human condition, Puiu's cinematic memento mori

forces the audience to face death, in line perhaps with Montaigne's

philosophy of "apprivoiser la mort" (taming of death). "Le scandale

de la mort" portrayed so movingly by Ionesco's Le Roi se meurt

{Exit the King) finds its Romanian version in Puiu's The Death of Mr

Lzrescu. The question remains: can this great "scandal," in fact,

ever become more bearable through art or any other means?

Notes

' The Romanian New Wave refers to a film style defined by a number

of characteristics, including quasi-documentary filming, long takes,

use of hand-held camera, naturally lit shots, a preference for facts

of quotidian existence, and a story that takes place over the course

of one day or evening. The camera typically follows the characters

very closely, revealing with disturbing closeness their discomfort,

anxiety, or confusion, as a result of which viewers are slowly drawn

into the actions and situation depicted. Despite the general gravity of

all these films, black humor features prominently. Philosophically, the

63

young film directors associated with this style embrace a certain type

of realism based largely on truthfulness and integrity, as opposed to

the old "allegorical" or "metaphorical" style of Romanian cinema,

a style inevitably adopted by artists forced to work in a society

suffocated politically and culturally by deception and fraud. However,

the filmmakers of this new generation reject the notion that their

individual artistic preferences can be mechanically subsumed under

a certain "movement" or "wave" and insist that nothing in their

directorial production could indicate that they should be regarded as a

unit. And yet, it is hard to deny the strong similarities connecting the

films produced by the new generation of filmmakers.

^ Other names that have become familiar to European and American

cinphiles are Comeliu Porumboiu, whose 12:08 East of Bucharest

won the Camra d'Or Prize, awarded to the best debut feature at the

Cannes Film Festival in 2006; Cristian Mungiu, axvQcior of 4Months, 3

Weeks, 2 Days, which won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival

in 2007; and Cristian Nemescu, who received the 2007 Un Certain

Regard award and the Satyajit Ray Humanitarian Award for debut

feature for his California Dreamin'. See A. O. Scott, "New Wave on

the Black Sea." New York Times Magazine, January 20, 2008: 30-35.

^ The Death of Mr Lzrescu was inspired by the real case of a 52-

year old Romanian man who, after a long journey from one hospital

to another, was literally abandoned by a paramedic in the street, where

he later died. A second source of inspiration was, according to Cristi

Puiu, his own hypochondria, the deep anxiety caused by the reading of

various medical books, and the irrational conviction that he suffered

from all the illnesses about which he was reading. Puiu needed one

year of therapy in order to recover from this temporary but serious

condition. Some of the doctors he consulted during that period treated

him inadequately and, at times, even rudely; therefore, this film

could be considered, to a certain extent, a response to their callous

and judgmental behavior. The doctors who condescend, humiliate,

or ignore Mr. Lzrescu in the film are perhaps largely modeled on

the arrogant and narcissistic doctors whom Puiu encountered during

his own suffering. Such doctors forget not only the main directive of

human love but also the Hippocratic oath, the very ethical foundation

that makes the medical profession a noble calling.

'' Some may read Mioara as Lzrescu's Virgil or as his Charonin

64

Greek mythology, the ferryman of Hades who carried the souls ofthe

deceased across the river Lethe that separated the world ofthe living

from that ofthe dead.

^ One is reminded of Barthes's notion of the "death of the author,"

which stresses the primacy of the literary text. In this case it is the

film director who appears to be absent during the seemingly self-

documenting film, leaving the viewer with a pure and independent

cinematic "text."

^ The Romanian New Wave directors have been acknowledging

their debt to Lucian Pintilie, the internationally celebrated director,

by avoiding large-scale productions and exotic special effects.

As Dominique Nasta rightly observes in her "The Tough Road to

Minimalism: Contemporary Romanian Film Aesthetics," "these

filmmakers have demonstrated a strong belief in the virtues of textual

and visual messages that are both very close to the ironic and absurdist

Romanian psyche, on the one hand, and able to achieve an intemational

audience appeal, on the other."

^ Interview with Cinefrum. ["Quando I fantasmi si liberano, non

esistono porte per bloccarli: intervista a Lucian Pintilie"]. Cinefrum

44.438 (2004): 53-7.

^ This black comedy is rooted in the Balkan tradition, represented in

Romania by the well-known 19th-century satirical playwright Ion

Luca Caragiale (1852-1912), whose work influenced to a certain

extent Ionesco's absurdist theatre.

Works cited

Barthes, Roland. "La mort de l'Auteur." Le bruissement de la langue.

Essais critiques IV, Paris: Seuil, 1984. 61-67.

Coates, Paul, ed. Lucid Dreams: The Films of Krzysztof Kieslowski.

Trowbridge, England: Flicks Books, 1999.

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema II: The Time-Image. Trans. Hugh Tomlinson

and Robert Galeta. London: Athlone P, 1989. 81.

Duma, Dana. "Cristi Puiu: The Death of Mr. Lazarescu."

kinokultura.eom/specials/6/duma.shtml, 2007.

65

Grierson, John. Grierson on Documentary. Ed. Forsyth Hard.

Berkeley: U of Califomia P, 1966. 225.

Ionesco, Eugne. Le Roi se meurt. Paris: Larousse, 1972.

Martea, Ion. On the Romanian New Wave, www.culturewars.org.uk/

index.php/site/article/on the romanian new wave

Morpurgo, Horatio. Cristi Puiu's The Death of Mr Lazarescu.

November 2006. www.threemonkevsonline.com/authors/Horatio_

Morpurgo.htm

Nasta, Dominique. "The Tough Road to Minimalism: Contemporary

Romanian Film Aesthetics." www.kinokultura.eom/specials/6/

nasta.shtml, 2007.

Rado, Petre. "A Little Bit of Patience." www.kinokultura.com/

specials/6/rado.shtml, 2007.

Sava, Valerian. "Un film de cinci stele: Moartea domnului Lazarescu."

www.observatorcultural.ro/Numaru 1-288 *numberlD_275-

summarv.html

Scott, A. O. "New Wave on the Black Sea." www.nytimes/2008/01/20/

magazine/20Romanian-t.html

Stojanova, Christina and Dana Duma. "The New Romanian

Cinema: Editorial Remarks." www.kinokultura.eom/specials/6/

introduction.shtml, 2007.

Wiseman, Frederick. Five Films by Frederick Wiseman: Titicut Follies,

High School, Welfare, High School IL Public Housing. Transcr.

and ed. Barry Keith Grant. Berkley: U of California P, 2006.

66

Copyright of Film Criticism is the property of Film Criticism and its content may not be copied or emailed to

multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users

may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- PIGEONDokument3 SeitenPIGEONPatata DokputNoch keine Bewertungen

- SsssDokument3 SeitenSsssPatata DokputNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review Plague of DovesDokument2 SeitenReview Plague of DovesloulousaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Old and New Masters by Lynd, Robert, 1879-1949Dokument122 SeitenOld and New Masters by Lynd, Robert, 1879-1949Gutenberg.org100% (1)

- The Day of Shelly's Death: The Poetry and Ethnography of Grief by Renato Rosaldo (Review)Dokument7 SeitenThe Day of Shelly's Death: The Poetry and Ethnography of Grief by Renato Rosaldo (Review)thaynáNoch keine Bewertungen

- Woyzeck Study GuideDokument9 SeitenWoyzeck Study GuideShanghaï LiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis of Edgar Allan PoeDokument9 SeitenAnalysis of Edgar Allan PoeOrifice xxNoch keine Bewertungen

- Poe's Short Stories PDFDokument7 SeitenPoe's Short Stories PDFAngela J MurilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Theatre of the Absurd Explores the Irrational Side of Human ExistenceDokument14 SeitenThe Theatre of the Absurd Explores the Irrational Side of Human ExistenceChristopher Daniel Serna RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faulkner's Sanctuary: Analysis of Characters and ThemesDokument17 SeitenFaulkner's Sanctuary: Analysis of Characters and ThemesRaouia ZouariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Slawomir Mrozek - Two Forms of The Absurd PDFDokument17 SeitenSlawomir Mrozek - Two Forms of The Absurd PDFMariusRusuNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Seagull: Full Text and Introduction (NHB Drama Classics)Von EverandThe Seagull: Full Text and Introduction (NHB Drama Classics)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (238)

- Kieslowski's Three ColorsDokument4 SeitenKieslowski's Three ColorskichutesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ibsen's Ghosts Critiques 19th Century MoralityDokument4 SeitenIbsen's Ghosts Critiques 19th Century MoralityROUSHAN SINGHNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Story of An HourDokument4 SeitenThe Story of An HourCrizelda CardenasNoch keine Bewertungen

- British and American DramaDokument13 SeitenBritish and American DramaRalucaVieruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tango Theatre Absurd DramaDokument16 SeitenTango Theatre Absurd DramaAleksandar JovanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- EN A Man Called OveDokument3 SeitenEN A Man Called OveAura TitianuNoch keine Bewertungen

- About The Darling Short StoryDokument12 SeitenAbout The Darling Short StoryMuhammad AshiqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sublimation: Death in Venice and The Aesthetics ofDokument3 SeitenSublimation: Death in Venice and The Aesthetics ofLilly VarakliotiNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHEKHOV - The Three SistersDokument7 SeitenCHEKHOV - The Three Sistersaa hnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Penny Dreadful Mashup Blends Frankenstein and PhantomDokument9 SeitenPenny Dreadful Mashup Blends Frankenstein and PhantomvikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sex and The ShakespeareDokument9 SeitenSex and The Shakespeareskpaul_muzaffarpur90% (10)

- Masochistic Art of Fantasy The Literary PDFDokument33 SeitenMasochistic Art of Fantasy The Literary PDFmarinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Masque of The Red DeathDokument5 SeitenThe Masque of The Red DeathGorgos Roxana-MariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Character Analysis of J. Alfred Prufrock in T.S. Eliot's PoemDokument3 SeitenCharacter Analysis of J. Alfred Prufrock in T.S. Eliot's PoemMd Abdul MominNoch keine Bewertungen

- (Arora, N., & Resch, S.) Undoing Gender, Nexus of Complicity and Acts of Subversion in The Piano Teacher and BlackSwanDokument22 Seiten(Arora, N., & Resch, S.) Undoing Gender, Nexus of Complicity and Acts of Subversion in The Piano Teacher and BlackSwanBatista.100% (1)

- Three Sisters by Anton Chekhov Story ofDokument5 SeitenThree Sisters by Anton Chekhov Story ofSammy Buso-MNoch keine Bewertungen

- Short Story Analysis 1-Author and Summary Masque of The Red DeathDokument2 SeitenShort Story Analysis 1-Author and Summary Masque of The Red DeathCélia ZENNOUCHENoch keine Bewertungen

- Swann's Way Tells Two Related Stories, The First of Which Revolves (Forog) AroundDokument4 SeitenSwann's Way Tells Two Related Stories, The First of Which Revolves (Forog) AroundTuzson RékaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCENE 03 traduçãoZUMBÃODokument65 SeitenSCENE 03 traduçãoZUMBÃOcuriangoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Thesmophoriazusae (Or The Women's Festival)Von EverandThe Thesmophoriazusae (Or The Women's Festival)Bewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (19)

- Don't shit yourself: Horror Stories, Urban Legends, Real EventsVon EverandDon't shit yourself: Horror Stories, Urban Legends, Real EventsNoch keine Bewertungen

- SESSION 5 PH M Thùy Trang 1622205Dokument7 SeitenSESSION 5 PH M Thùy Trang 1622205denglijun1712Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poe's Gothic Masterpiece: The Fall of the House of UsherDokument5 SeitenPoe's Gothic Masterpiece: The Fall of the House of Usherabekhti2008100% (1)

- The BearDokument14 SeitenThe BearraguaswithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Analysis of The Masque of Red DeathDokument13 SeitenLiterary Analysis of The Masque of Red DeathAbdulhakim MautiNoch keine Bewertungen

- LA Times - A Double Twist On Life - (перекласти)Dokument3 SeitenLA Times - A Double Twist On Life - (перекласти)Валя БоберськаNoch keine Bewertungen

- Book PresentationDokument6 SeitenBook Presentationpaula hiraldoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 08 - Chapter 2 PDFDokument24 Seiten08 - Chapter 2 PDFArvind DhankharNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Dutch CourtesanDokument5 SeitenThe Dutch CourtesanElena ȚăpeanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Three Sisters), and Вишнëвый сад (The Cherry Orchard) - He was, however, much moreDokument3 SeitenThree Sisters), and Вишнëвый сад (The Cherry Orchard) - He was, however, much moreDerrick KileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Christopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (2013 Globe Theatre PerformanceDokument1 SeiteChristopher Marlowe's Doctor Faustus (2013 Globe Theatre Performancetipsyturtle1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Absurdtheatre 1124873Dokument14 SeitenAbsurdtheatre 1124873haydar severgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Essay 1Dokument5 SeitenEssay 1api-315992820Noch keine Bewertungen

- Love in The New Millenioum - Can XueDokument322 SeitenLove in The New Millenioum - Can XueDANNY RICARDO CANO PORTILLANoch keine Bewertungen

- The Chambermaid Mirbeau to BuñuelDokument7 SeitenThe Chambermaid Mirbeau to BuñuelAnonymous 5r2Qv8aonfNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Monypenny Breviary: A Rare Manuscript Illuminated with Portraits and Arms of a Franco-Scottish FamilyDokument39 SeitenThe Monypenny Breviary: A Rare Manuscript Illuminated with Portraits and Arms of a Franco-Scottish FamilyCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Coins of Sweden: A Brief HistoryDokument78 SeitenThe Coins of Sweden: A Brief HistoryDavid Ruckser50% (2)

- Menage - The Annals of Murad IIDokument16 SeitenMenage - The Annals of Murad IICristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experience and Conceptualisation of Installation ArtDokument9 SeitenExperience and Conceptualisation of Installation ArtMaja SkenderovićNoch keine Bewertungen

- Codrington. A Manual of Musalman NumismaticsDokument256 SeitenCodrington. A Manual of Musalman NumismaticsCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Theories of Social Remembering 22 To 38Dokument17 SeitenTheories of Social Remembering 22 To 38Cristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bishop 001Dokument42 SeitenBishop 001Towers Marrow BeatrizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tips For Writing Goals and ObjectivesDokument2 SeitenTips For Writing Goals and ObjectivespiyushranuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Names and Titles On Islamic CoinsDokument1 SeiteNames and Titles On Islamic CoinsCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Susan Sontag - On Photography - ExcerptDokument5 SeitenSusan Sontag - On Photography - ExcerptparallelogramNoch keine Bewertungen

- OrlandoDokument7 SeitenOrlandoCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pavement of Cathed 00 Sie Nu of TDokument72 SeitenPavement of Cathed 00 Sie Nu of TCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hahn. 1997. The Voices of The SaintsDokument13 SeitenHahn. 1997. The Voices of The SaintsCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- OrlandoDokument25 SeitenOrlandoCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samuel Beckett - Not IDokument8 SeitenSamuel Beckett - Not Iapi-3852542100% (19)

- JesseDokument15 SeitenJesseCristiana TataruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strong Letter of Recommendation for Radiology ResidencyDokument1 SeiteStrong Letter of Recommendation for Radiology Residencydrsanjeev15Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cold Laser: Dr. Amal Hassan MohammedDokument46 SeitenCold Laser: Dr. Amal Hassan MohammedAmal IbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Urban HydrologyDokument39 SeitenUrban Hydrologyca rodriguez100% (1)

- 1 Cell InjuryDokument44 Seiten1 Cell Injuryrithesh reddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post Stroke DepressionDokument15 SeitenPost Stroke DepressionJosefina de la IglesiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- IC 4603 L01 Lab SafetyDokument4 SeitenIC 4603 L01 Lab Safetymunir.arshad248Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rina Arum Rahma Dan Fitria Prabandari Akademi Kebidanan YLPP PurwokertoDokument14 SeitenRina Arum Rahma Dan Fitria Prabandari Akademi Kebidanan YLPP PurwokertoYetma Triyana MalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flying Risk Factors and Personal Minimums ChecklistDokument62 SeitenFlying Risk Factors and Personal Minimums ChecklistlydiamoraesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 GRAM-Positive - Cocci - Staphylococci 5 GRAM - Positive - Cocci - StaphylococciDokument5 Seiten5 GRAM-Positive - Cocci - Staphylococci 5 GRAM - Positive - Cocci - StaphylococciJoseline SorianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Affidavit of Karl Harrison in Lawsuit Over Vaccine Mandates in CanadaDokument1.299 SeitenAffidavit of Karl Harrison in Lawsuit Over Vaccine Mandates in Canadabrian_jameslilley100% (2)

- Mortality and Morbidity CHNDokument19 SeitenMortality and Morbidity CHNPamela Ria HensonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Nursing: Urinary Elimination, Catheterization, Ostomy Care & Pain ManagementDokument29 SeitenFundamentals of Nursing: Urinary Elimination, Catheterization, Ostomy Care & Pain ManagementKatrina Issa A. GelagaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abstractbook Nsctls-2021 FinalDokument141 SeitenAbstractbook Nsctls-2021 Finalijarbn editorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neuro ImagingDokument41 SeitenNeuro ImagingNauli Panjaitan100% (1)

- Child AbuseDokument3 SeitenChild AbuseUthuriel27Noch keine Bewertungen

- Edu501 M4 SLP 2023Dokument5 SeitenEdu501 M4 SLP 2023PatriciaSugpatanNoch keine Bewertungen

- F&C Safety Data Sheet Catalog No.: 315407 Product Name: Ammonia Solution 25%Dokument7 SeitenF&C Safety Data Sheet Catalog No.: 315407 Product Name: Ammonia Solution 25%Rizky AriansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Section Valves Placement (Pipeline)Dokument2 SeitenSection Valves Placement (Pipeline)amnaNoch keine Bewertungen

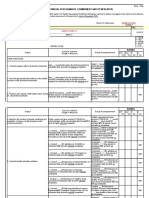

- Individual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledDokument12 SeitenIndividual Performance Commitment and Review (Ipcr) : Name of Employee: Approved By: Date Date FiledTiffanny Diane Agbayani RuedasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Floor Hockey Block PlanDokument4 SeitenFloor Hockey Block Planapi-249766784Noch keine Bewertungen

- MSBT Maharashtra Summer Exam HEC Model AnswersDokument25 SeitenMSBT Maharashtra Summer Exam HEC Model AnswersAbhi BhosaleNoch keine Bewertungen

- FastingDokument36 SeitenFastingMaja Anđelković92% (12)

- Delta-Product - M1304VWCDokument3 SeitenDelta-Product - M1304VWCdhruvit_159737548Noch keine Bewertungen

- Factors That Determine Community HealthDokument6 SeitenFactors That Determine Community HealthMarz AcopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sydney Mattern RD ResumeDokument2 SeitenSydney Mattern RD Resumeapi-498054141Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lower Gi Finals 2019Dokument51 SeitenLower Gi Finals 2019Spring BlossomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myanmar OH Profile OverviewDokument4 SeitenMyanmar OH Profile OverviewAungNoch keine Bewertungen

- IPHO Accomplishment Report For May 2018Dokument12 SeitenIPHO Accomplishment Report For May 2018ebc07Noch keine Bewertungen

- Development Psychology - Chapter 7 (Santrock)Dokument59 SeitenDevelopment Psychology - Chapter 7 (Santrock)Shaine C.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Checklist of Documentary Requirements Maternity Benefit Reimbursement ApplicationDokument3 SeitenChecklist of Documentary Requirements Maternity Benefit Reimbursement Applicationrhianne_lhen5824Noch keine Bewertungen