Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Tooth Display and Lip Position - 49

Hochgeladen von

drgayen6042Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Tooth Display and Lip Position - 49

Hochgeladen von

drgayen6042Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

This article was downloaded by:[UVA Universiteitsbibliotheek SZ]

On: 15 July 2008

Access Details: [subscription number 790385164]

Publisher: Informa Healthcare

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954

Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Acta Odontologica Scandinavica

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713394069

Tooth display and lip position during spontaneous and

posed smiling in adults

Pieter Van Der Geld

a

; Paul Oosterveld

a

; Stefaan J. Berg

b

; Anne M.

Kuijpers-Jagtman

a

a

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Biology, Radboud University Nijmegen

Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

b

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Radboud University Nijmegen

Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

Online Publication Date: 01 January 2008

To cite this Article: Van Der Geld, Pieter, Oosterveld, Paul, Berg, Stefaan J. and

Kuijpers-Jagtman, Anne M. (2008) 'Tooth display and lip position during

spontaneous and posed smiling in adults', Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 66:4,

207 213

To link to this article: DOI: 10.1080/00016350802060617

URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00016350802060617

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf

This article maybe used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction,

re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly

forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be

complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be

independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings,

demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or

arising out of the use of this material.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Tooth display and lip position during spontaneous and posed smiling

in adults

PIETER VAN DER GELD

1

, PAUL OOSTERVELD

1

, STEFAAN J. BERGE

2

&

ANNE M. KUIJPERS-JAGTMAN

1

1

Department of Orthodontics and Oral Biology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands

and

2

Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The

Netherlands

Abstract

Objective. To analyze differences in tooth display, lip-line height, and smile width between the posed smiling record,

traditionally produced for orthodontic diagnosis, and the spontaneous (Duchenne) smile of joy. Material and methods.

The faces of 122 male participants were each filmed during spontaneous and posed smiling. Spontaneous smiles were

elicited through the participants watching a comical movie. Maxillary and mandibular lip-line heights, tooth display, and

smile width were measured using a digital videographic method for smile analysis. Paired sample t-tests were used to

compare measurements of posed and spontaneous smiling. Results. Maxillary lip-line heights during spontaneous smiling

were significantly higher than during posed smiling. Compared to spontaneous smiling, tooth display in the (pre)molar area

during posed smiling decreased by up to 30%, along with a significant reduction of smile width. During posed smiling, also

mandibular lip-line heights changed and the teeth were more covered by the lower lip than during spontaneous smiling.

Conclusions. Reduced lip-line heights, tooth display, and smile width on a posed smiling record can have implications for

the diagnostics of lip-line height, smile arc, buccal corridors, and plane of occlusion. Spontaneous smiling records next to

posed smiling records are therefore recommended for diagnostic purposes. Because of the dynamic nature of spontaneous

smiling, it is proposed to switch to dynamic video recording of the smile.

Key Words: Dental esthetics, dental photography, diagnosis, facial expression, orthodontics

Introduction

Dentofacial and smile esthetics have become im-

portant factors in a patients motivation for ortho-

dontic therapy [1]. From a dental point of view, an

esthetically attractive smile is a harmonious entity of

oral components in which the liptooth relationships

are crucial factors [2,3], and to evaluate these

relationships, a smiling record of the patient is

required. Traditionally, photography is used for an

orthodontic record [4], but new videographic and

computer technologies have enabled other diagnos-

tic assessments. Several authors have described a

face analysis based on digital videography in which

visual constructs such as buccal corridors and smile

arc are important in orthodontic treatment planning

[57]. Most articles are descriptive and therefore do

not represent new discoveries compelling orthodon-

tists to apply these methods for better treatments.

Studies evaluating the use of digital videography for

developing criteria to aid specifically in orthodontic

diagnosis are rare [3,8,9].

In the dental field, Tarantili et al. [10] studied lip

movements during spontaneous smiling in a sample

of children. A videographic method was used. Their

findings about the dynamics of the spontaneous

smile raised concern about the validity of a single

photographic capture for esthetic assessment. With

the photographic methods available in the past,

however, only the posed smile was considered

reproducible [11,12]. The simple and reproducible

registration of a social smile is an advantage of the

posed smile record. A disadvantage is that posed

smiling can be influenced in its expression by the

individuals social skills and emotional background

(Received 9 January 2008; accepted 17 March 2008)

ISSN 0001-6357 print/ISSN 1502-3850 online # 2008 Informa UK Ltd. (Informa Healthcare, Taylor & Francis As)

DOI: 10.1080/00016350802060617

Correspondence: Anne M. Kuijpers-Jagtman, Department of Orthodontics and Oral Biology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, 309

Tandheelkunde, P.O. Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, The Netherlands. Tel: 31 (0)24 361 4005. Fax: 31 (0)24 354 0631. E-mail:

orthodontics@dent.umcn.nl

Acta Odontologica Scandinavica, 2008; 66: 207213

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

[13]. This can result in an unnatural or asymmetric

smile. Examples of emotional factors influencing the

posed smile are: shame with ones oral appearance or

embarrassment about phobic dental anxiety [14,15].

Those patients can show a learned smile or inhibited

smiling by hiding with the lips, hands, or changing

the head position. Other examples of interfering

emotional factors on posed smiling are feelings of

shame from victims of non-disclosed childhood

sexual abuse or negative self-esteem of cleft lip and

palate patients [16,17].

From the starting point that the spontaneous smile

is an authentic emotion compared to posed smiling

and therefore a logical focus point in smile diagnos-

tics, a digital videographic measurement method was

tested by Van der Geld et al. [18] for reliability

during both spontaneous and posed smiling. Central

ideas behind this technique were that a spontaneous

smile of joy must be recorded precisely at the exact

moment, and that recording it should be done with

minimal patient interference. The faces of partici-

pants were filmed individually during spontaneous

and posed smiling. Spontaneous smiles were elicited

with the participants watching an comical movie.

Lip-line heights and tooth display were measured

using a digital videographic method for smile analy-

sis. This measurement method showed high relia-

bility; not just posed smiles but also spontaneous

smiles were measured reproducibly. Based on these

results, further study was suggested into the rele-

vance of this video technology for practical diagnos-

tic concerns. The question remains whether

videographic spontaneous smiling records are com-

plementary to posed smiling records for orthodontic

diagnosis. In an evaluation of liptooth character-

istics during speech and posed smiling in adoles-

cents, Ackerman et al. [8] proposed viewing the

dynamics of anterior tooth display as a continuum

delineated by the time-points of rest, speech, posed

social smile, and the spontaneous smile. However,

since no data are available on differences between

adult liptooth relationships during spontaneous and

posed smiling, the aim of this study was to analyze

differences in tooth and gingival display and lip-line

heights between the spontaneous smile of joy and the

posed social smile.

Material and methods

Participants

Of 1069 military men at an airforce base, 122 were

randomly selected from three age cohorts (2025

years; 3540 years; 5055 years). Inclusion criteria

were full maxillary and mandibular dental arches up

to and including the 1st molar and Caucasian race.

The research proposal was approved by the ethics

committee of the Academic Centre of Dentistry in

Amsterdam. Informed consent was obtained from

the participants in accordance with the guidelines of

that institution.

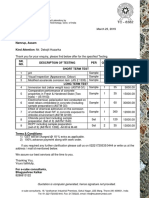

Videographic measurement of spontaneous smiling and

posed smiling

A digital videographic measurement method was

used to capture records of a spontaneous smile of joy

and a posed social smile (Figure 1). This method

had been extensively tested for measuring tooth

display and lip position during spontaneous and

posed smiling, showing intra-class coefficients ran-

ging from 0.99 to 0.80 [18]. In addition, a full

dentition record with the aid of cheek retractors was

made.

On the full dentition record, tooth length was

measured to obtain the actual length of tooth

crowns. On the spontaneous and posed smiling

records, the display of the teeth and gingiva was

measured. In the maxilla and mandible, a central

and lateral incisor, a canine, a 1st and 2nd premolar,

and a 1st molar were measured. The most incisal

points of each tooth (line 1) and the lip edge (line 2)

were marked with a digital horizontal line parallel to

the pupil line (Figure 2). The vertical distance

between these lines was measured (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Examples of (a) a spontaneous smile and (b) a posed

smile.

208 P. van der Geld et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

Following Peck & Peck [19], lip-line height was

expressed relative to the gingival margin (line 3) and

is thus a measure of both tooth and gingival visibility

(Figure 2). Lip-line height was calculated as the

difference between lip position and tooth length

(Figure 2). When the gingival margin was displayed,

positive values were given in both the maxilla and

mandible. When the teeth remained partly covered,

negative values were given. Sometimes the upper

and lower lips covered both the gingival margin and

incisal point, in which case lip-line height was

denoted as not measurable. If a tooth was not

visible, lip-line height was coded as missing.

Next to lip-line height, the percentages of tooth

display during spontaneous and posed smiling were

calculated for each tooth. The amount of tooth

display was expressed as the percentage of the actual

length of the tooth crown. If a tooth was not visible,

the percentage of tooth display was zero.

On the records of spontaneous smiling and posed

smiling, the corners of the mouth were marked with

a vertical line. The horizontal distance between the

corners of the mouth was measured as the inter-

commissure distance (smile width).

Data analysis

Paired sample t-tests were used to compare lip-line

heights and percentage tooth display during sponta-

neous and posed smiling for each tooth. The paired

sample t-test was performed on each tooth sepa-

rately, because the number of teeth displayed varied

between situations, barring a multivariate approach.

The same procedure was used for the inter-commis-

sure distances.

Results

In Figure 3 and 4, both mean lip-line heights and

mean percentages of tooth display during sponta-

neous and posed smiling are shown for the maxilla

and mandible, respectively. The graphs of lip-line

heights include the displayed teeth during smiling.

The graphs of percentage tooth display also include

not showing teeth with zero percent display.

Figure 3a indicates that maxillary lip-line heights

during spontaneous smiling are higher than during

posed smiling. The course of both graphs is compar-

able and the interspaces remain relatively stable. In

Figure 3b, the graphs of tooth display for the

maxillary anterior teeth follow the same pattern as

those of lip-line height (Figure 3a). In the (pre)molar

area the interspaces between the tooth display graphs

increase towards the posterior: tooth display during

posed smiling is decreased considerably compared to

spontaneous smiling.

The graphs of lip-line height in Figure 4a show

that during posed smiling the mandibular teeth are

more covered by the lower lip than during sponta-

neous smiling. The graphs of tooth display in Figure

4b show fewer interspaces in the posterior area,

where tooth display is relatively low in both situa-

tions, i.e. varying between 19% and 1%.

Figure 2. Measurement of the lip-line height. Line 1: marking of

the most incisal point of the central incisor. Line 2: marking of the

lip edge on the central incisor. Line 3: cervical gingival margin of

the central incisor. Lip-line height is lip position minus tooth

length. When the gingival margin is displayed, lip-line height has

positive values. When the teeth are partly covered, lip-line height

has negative values.

Figure 3. (a) Means of maxillary lip-line heights in millimetres

relative to the gingival margin for upper incisors, canine,

premolars and 1st molar, and (b) means of percentage maxillary

tooth display for upper incisors, canine, premolars, and 1st molar.

The vertical bars represent the 95% condence intervals.

Spontaneous and posed smiling lip lines 209

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

The results of the paired samples t-tests for lip-line

heights during spontaneous and posed smiling are

given in Table I. For all maxillary teeth and

mandibular incisors, canine, and 1st premolar, the

significant p-values strongly support the assumption

of structural differences in lip-line heights between

spontaneous and posed smiling.

The results for the paired samples t-tests for

percentage tooth display during spontaneous and

posed smiling are given in Table II. Tooth display in

all teeth showed significant differences between

spontaneous and posed smiling.

The paired samples t-test was also used to

determine differences in inter-commissure distances

during spontaneous and posed smiling. During

spontaneous smiling, the mean inter-commissure

distance was 68.2 mm, and for posed smiling

65.8 mm. The mean difference was 2.4 mm, and

the assumption of a structural difference was

strongly supported by the significant p-value (diff.

SD3.1 mm, t 8.4, d.f. 121, pB0.001).

Discussion

With the traditional photographic techniques, only a

posed smile was considered adequate to obtain a

reproducible diagnostic record [11,12]. A study with

contemporary available digital videography has

shown that also a spontaneous smile of joy is

measurable with a more observational and less

patient-interfering approach [18]. With this video-

graphic method, spontaneous smiling and posed

smiling were captured reproducibly. The central

question in this study is whether the use of a posed

smile rather than a spontaneous smile is sufficient as

a diagnostic record for facial esthetics and, more

specifically, liptooth relationships. Besides, the

spontaneous smile is a more relevant emotion than

a photographic posed smile and approaches the way

patients are perceived by their social environment.

For most patients, the outcome of orthodontic

therapy is directly related to visible improved dento-

facial attractiveness and not so much to the more

invisible occlusal relationships according to scientific

standards. This ambivalence is experienced by some

orthodontists, who consider orthodontics as much

an art as a science [7,20]. Nevertheless, diagnosis

Table I. Paired samples t-tests of lip-line heights during spontaneous and posed smiling in the maxilla and mandible.

I1 I2 C P1 P2 M1

Maxilla

Mean diff. (mm) 0.9 1.2 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.5

SD diff. (mm) 1.1 1.2 1.4 1.7 1.7 1.8

t 8.8 11.1 10.1 9.0 8.3 5.3

d.f. 115 117 90 94 77 41

p-value pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001

Mandible

Mean diff. (mm) 1.1 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.0 1.1

SD diff. (mm) 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.4 1.6 2.3

t 4.4 3.8 3.7 3.4 1.8 0.8

d.f. 45 42 40 21 8 2

p-value pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 0.103 0.502

Figure 4. (a) Means of mandibular lip-line heights in millimetres

relative to the gingival margin for upper incisors, canine,

premolars, and 1st molar, and (b) means of percentage mandib-

ular tooth display for upper incisors, canine, premolars, and 1st

molar. The vertical bars represent the 95% condence intervals.

210 P. van der Geld et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

should be both valid and reliable and should not just

consider the brief intervals involving active treat-

ments. The profound changes from natural aging on

the relations between soft tissue and dentition

should also be included in orthodontic diagnosis

and treatment planning [21]. An effect of age

resulting in a significant reduction of maxillary lip-

line heights was quantified in a recent study [9].

The present study shows significantly higher lip-

line heights for spontaneous smiling compared to

posed smiling (Figure 3a, 4a and Table I). The mean

reductions in maxillary lip-line height during posed

smiling varied between about 1 mm in the anterior

area and 1.5 mm in the posterior area. This,

however, is only relevant when lip-line heights are

displayed and measurable. The maxillary anterior

teeth and 1st premolar could be measured in more

than three-quarters of the sample, but at the 1st

molar measurable lip-line heights were restricted to a

third of the sample. Therefore, in this study design,

also tooth display percentages were used to quantify

differences between spontaneous and posed smiling.

These differences are especially explicit in Figure 3b,

where tooth display differences in the posterior

maxillary teeth between spontaneous and posed

smiling increase to 30%. This means that during

spontaneous smiling the 2nd premolar and 1st molar

are much more visible than during posed smiling.

This is supported by the significant reduction in

inter-commissure distance (smile width) of posed

smiling compared to spontaneous smiling.

In the mandible, the mean differences for lip-line

heights remained stable at around 1 mm. The graphs

of tooth display (Figure 4b) show that from an

esthetic point of view the differences between

spontaneous and posed smiling are most relevant

for the mandibular anterior teeth.

Significance testing in this study involved multiple

t-tests, because a multivariate approach was not

possible due to a varying number of observations

per tooth. The significance level for multiple tests,

however, is not identical to the significance level for

each separate test. There is an increased risk of

unjustified rejection of the null hypothesis, which

can be countered with the Bonferroni procedure.

This involves dividing the desired overall alpha by

the number of tests performed. Adopting this, rather

conservative, approach for the data in Table I and II

and adopting a significance level of p0.0083 (0.05/

12) would result in the same pattern of rejecting or

not rejecting the null hypotheses.

The results of this study demonstrate that a posed

smiling record differs from a spontaneous smiling

record in several essential aspects. Therefore the

traditionally used posed smiling record is a starting

point that may involve a number of risks for the

diagnosis and predictability of the orthodontic treat-

ment plan, but also for a combined orthodontic

surgical approach. Firstly, the lip-line height, which

is reduced during posed smiling, can be assessed too

low on a posed smiling record. Particularly in the

case of gummy smile patients, who have the mus-

cular ability to raise the upper lip significantly higher

than average on smiling [19], underestimation of the

lip-line height can seriously influence treatment

outcome. Lip-line height is also a dominating factor

in the combined orthodontic and restorative-im-

plantology approach (e.g. in cases of trauma or

oligodontia), where the esthetic risk of the therapy

increases when the lip line reveals more of the teeth

and gingival area. A natural looking implant restora-

tion, including correct shape of the alveolar bone, a

harmonious gingival line, and an inter-proximal

dental papilla to the contact point, is not always

achievable in clinical practice. In that case, the

height of the lip line is decisive whether the esthetic

shortcomings of the combined therapy are masked

by the lip or just revealed [22].

Not only is lip-line height reduced during posed

smiling, also the posterior teeth can be considerably

less displayed in combination with reduced smile

width. This can lead to insufficient and inadequate

diagnostics regarding arch width and buccal corri-

dors, smile arc and transversal occlusal plane, and

(pre)molar lip-line height. Since minimal buccal

corridors are a preferred esthetic feature in both

men and women, large buccal corridors are consid-

ered a serious problem that has to be included in the

Table II. Paired samples t-tests of tooth display (in percent) during spontaneous and posed smiling in the maxilla and mandible.

I1 I2 C P1 P2 M1

Maxilla

Mean diff (%) 7.5 7.9 11.2 15.0 20.2 33.1

SD diff (%) 13.2 13.7 16.5 20.9 26.9 35.2

t 6.3 6.4 7.5 7.9 8.3 10.4

d.f. 121 121 121 121 121 121

p-value pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001

Mandible

Mean diff. (%) 12.2 11.7 11.0 9.6 6.8 6.0

SD diff. (%) 21.6 20.8 18.7 20.5 17.1 18.7

t 6.2 6.2 6.5 5.2 4.4 3.5

d.f. 121 121 121 121 121 121

p-value pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.001 pB0.01

Spontaneous and posed smiling lip lines 211

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

problemlist during orthodontic diagnosis [23]. How-

ever, as a result of reduced smile width during posed

smiling, the buccal corridors can be underestimated

and upper arch widening not deemed to be needed

during orthodontic or surgical treatment.

In relation to the maxillary arch width, the curve of

the smile arc is also considered an important part of

oral esthetics [5,24]. The curve of the smile arc is

established in relation to the curve of the lower lip.

This is complicated by the reduced visibility of the

maxillary (pre)molar area on a posed smiling record.

During posed smiling, the upper lip is less elevated

and the mouth less open. As a result, the cervical

parts of the (pre)molars are more covered by the

upper lip and the incisal parts by the lower lip,

especially near the commissurae. When the incisal

line through the cusps is covered, only information

regarding the smile arc in the anterior teeth is

available for the diagnosis. In that case, control is

lacking over an esthetic sagittal alignment of the

posterior teeth, for which the cephalogram gives

insufficient hold. Moreover, the smaller smile width

during posed smiling can readily result in a flatter

curve of the lower lip at the risk of a flat smile arc also

in the anterior teeth during spontaneous smiling.

Next to spontaneous smiling, a videographic

analysis can easily be extended to other frequently

used functional expressions. Liptooth relationships

during speech and at rest can be captured and

analyzed according to the classic dynesthetic prin-

ciples forthcoming from prosthodontics [25]. Atten-

tion can then be given to the speaking line, the

displayed incisal length of the maxillary anterior

teeth during speech and to tooth display at rest.

When speaking, the lateral incisors should be partly

shown. At rest, a few millimeters of the maxillary

anterior teeth should be displayed depending on

gender and age of the patient. During speech, a

larger number of mandibular teeth are in view and

are also more exposed than during smiling [9]. In

this way, more information is obtained for an

harmonious mandibular tooth positioning and cur-

vature through the incisal edges and cusps. Whether

additional videography of speech and at rest leads to

another orthodontic treatment strategy remains to

be seen, but in a recent study it was demonstrated

that there is a significant individual coherence for

upper lip positions at the maxillary anterior teeth

during spontaneous smiling, speech, and at rest [9].

The results show, without doubt, that sponta-

neous and posed smiling are different. Not surpris-

ingly, as Duchenne de Boulogne observed already in

1862, spontaneous and posed smiles exhibit phy-

siognomic differences [26]. Next to the zygomaticus

major muscle, contracting the corners of the mouth,

the spontaneous Duchenne smile also involves the

orbicularis oculi pars lateralis muscle. Contraction of

this muscle results in crows feet at the outer

corners of the eye, which cannot be done voluntarily

[27]. Further psychophysiological research has

found more asymmetries in posed smiles than in

spontaneous smiles and different dynamic time

patterns [28,29].

Spontaneous smiling should be the logical focus

point for the esthetic diagnosis of liptooth relation-

ship during smiling. The fast onset and fading out of

a spontaneous smile makes it impossible to capture

in the right moment with a static photograph.

Therefore it is proposed to switch from static to

dynamic videorecording of the smile for diagnostic

purposes. Experiences of plastic surgeons [30,31],

oral and maxillofacial surgeons [32], and orthodon-

tists [7] show that (digital) video registration in

clinical practice is feasible.

Declaration of interest: The authors report no

conflicts of interest. The authors alone are respon-

sible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

[1] Berg R. Orthodontic treatment yes or no? A difcult

decision in some cases. A contribution to the discussion. J

Orofac Orthop 2001;62:41021.

[2] Kokich VO Jr, Kiyak HA, Shapiro PA. Comparing the

perception of dentists and lay people to altered dental

esthetics. J Esthet Dent 1999;11:31124.

[3] van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, van Heck G, Kuijpers-Jagtman

AM. Smile attractiveness: self-perception and inuence on

personality. Angle Orthod 2007;77:75965.

[4] Ritter DE, Gandini LG Jr, dos Santos Pinto A, Ravelli DB,

Locks A. Analysis of the smile photograph. World J Orthod

2006;7:27985.

[5] Sarver DM. The importance of incisor positioning in the

esthetic smile: the smile arc. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2001;120:98111.

[6] Ackerman MB, Ackerman JL. Smile analysis and design in

the digital era. J Clin Orthod 2002;36:22136.

[7] Sarver DM, Ackerman MB. Dynamic smile visualization and

quantication. Part 1: Evolution of the concept and dynamic

records for smile capture. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop

2003;124:412.

[8] Ackerman MB, Brensinger C, Landis JR. An evaluation of

dynamic liptooth characteristics during speech and smile in

adolescents. Angle Orthod 2004;74:4350.

[9] van der Geld P, Oosterveld P, Kuijpers-Jagtman AM. Age-

related changes of the dental aesthetic zone during sponta-

neous smiling and speech. Eur J Orthod 2008. In press.

[10] Tarantili VV, Halazonetis DJ, Spyropoulos MN. The spon-

taneous smile in dynamic motion. Am J Orthod Dentofacial

Orthop 2005;128:815.

[11] Rigsbee OH 3rd, Sperry TP, BeGole EA. The inuence of

facial animation on smile characteristics. Int J Adult Ortho-

don Orthognath Surg 1988;3:2339.

[12] Ackerman JL, Ackerman MB, Brensinger CM, Landis JR. A

morphometric analysis of the posed smile. Clin Orthod Res

1998;1:211.

[13] Ekman P. Facial expressions of emotion: an old controversy

and new ndings. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci

1992;335:639.

[14] Allen E, Bell W. Enhancing facial esthetics through gingival

surgery. In: Bell WH, editors. Modern practice in orthog-

nathic and reconstructive surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders;

1992. p. 23551.

212 P. van der Geld et al.

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

B

y

:

[

U

V

A

U

n

i

v

e

r

s

i

t

e

i

t

s

b

i

b

l

i

o

t

h

e

e

k

S

Z

]

A

t

:

1

5

:

2

8

1

5

J

u

l

y

2

0

0

8

[15] Moore R, Brdsgaard I, Rosenberg N. The contribution of

embarrassment to phobic dental anxiety: a qualitative

research study. BMC Psychiatry 2004;4:10.

[16] Bonanno GA, Keltner D, Noll JG, Putnam FW, Trickett PK,

LeJeune J, et al. When the face reveals what words do not:

facial expressions of emotion, smiling, and the willingness to

disclose childhood sexual abuse. J Pers Soc Psychol 2002;

83:94110.

[17] Adachi T, Kochi S, Yamaguchi T. Characteristics of non-

verbal behavior in patients with cleft lip and palate during

interpersonal communication. Cleft Palate Craniofac J 2003;

40:31016.

[18] van der Geld PA, Oosterveld P, van Waas MA, Kuijpers-

Jagtman AM. Digital videographic measurement of tooth

display and lip position in smiling and speech: reliability and

clinical application. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2007;

131:301.e1e8.

[19] Peck S, Peck L. Selected aspects of the art and science of

facial esthetics. Semin Orthod 1995;1:10526.

[20] Mackley RJ. Animated orthodontic treatment planning. J

Clin Orthod 1993;27:3615.

[21] Zachrisson BU. Esthetic factors involved in anterior tooth

display and the smile: vertical dimension. J Clin Orthod

1998;23:43245.

[22] Cune MS, Meijer GJ, Koole R. Anterior tooth replacement

with implants in grafted alveolar cleft sites: a case series. Clin

Oral Implant Res 2004;15:61624.

[23] Moore T, Southard KA, Casko JS, Qian F, Southard TE.

Buccal corridors and smile esthetics. Am J Orthod Dento-

facial Orthop 2005;127:20813.

[24] Parekh S, Fields HW, Beck FM, Rosenstiel SF. The

acceptability of variations in smile arc and buccal corridor

space. Orthod Craniofacial Res 2007;10:1521.

[25] Frush JP, Fisher RD. The dynesthetic interpretation of the

dentogenic concept. J Prosthet Dent 1958;8:55881.

[26] Ekman P, Davidson RJ, Friesen WV. The Duchenne smile:

emotional expression and brain physiology. II. J Pers Soc

Psychol 1990;58:34253.

[27] Hess U, Kappas A, McHugo GJ, Kleck RE, Lanzetta JT. An

analysis of the encoding and decoding of spontaneous and

posed smiles: the use of facial electromyography. J Nonverbal

Behav 1989;13:12137.

[28] Skinner M, Mullen B. Facial asymmetry in emotional

expression: a meta-analysis of research. Br J Soc Psychol

1991;30:11324.

[29] Hess U, Kleck RE. Differentiating emotion elicited and

deliberate emotional facial expressions. Eur J Soc Psychol

1990;20:36985.

[30] Frey M, Giovanoli P, Gerber H, Slameczka M, Stu ssi E.

Three-dimensional video analysis of facial movements: a new

method to assess the quantity and quality of the smile. Plast

Reconstr Surg 1999;104:20329.

[31] Kang YS, Bae YC, Hwang SM, Nam SB. A simple and

quantitative method for three-dimensional measurement of

normal smiles. Ann Plast Surg 2005;54:37983.

[32] Nooreyazdan M, Trotman CA, Faraway JJ. Modeling facial

movement. II. A dynamic analysis of differences caused

by orthognathic surgery. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004:62:

13806.

Spontaneous and posed smiling lip lines 213

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Literature Search Tracking LogDokument2 SeitenLiterature Search Tracking Logdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Selective Underlining 2Dokument1 SeiteSelective Underlining 2drgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Table of ContentsDokument5 SeitenTable of Contentsdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pre-Reading: Name: - Date: - PeriodDokument1 SeitePre-Reading: Name: - Date: - Perioddrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Readers' Round: Journal of Prosthetic DentisDokument1 SeiteReaders' Round: Journal of Prosthetic Dentisdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Theclinicsarenowavailableonline! Access Your Subscription atDokument1 SeiteTheclinicsarenowavailableonline! Access Your Subscription atdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Full Mouth Case-Sequence - Patient PDFDokument2 SeitenFull Mouth Case-Sequence - Patient PDFdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- BOXING UP MASTER IMPRESSIONS (Completes or Partials Dentures)Dokument1 SeiteBOXING UP MASTER IMPRESSIONS (Completes or Partials Dentures)drgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Annotating A TextDokument5 SeitenAnnotating A TextMayteé AgmethNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gagging Prevention Using Nitrous Oxide or Table Salt: A Comparative Pilot StudyDokument3 SeitenGagging Prevention Using Nitrous Oxide or Table Salt: A Comparative Pilot Studydrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gagging Prevention Using Nitrous Oxide or Table Salt: A Comparative Pilot StudyDokument3 SeitenGagging Prevention Using Nitrous Oxide or Table Salt: A Comparative Pilot Studydrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dentures PDFDokument1 SeiteDentures PDFdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Preface To The Eighth Edition: The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry The Academy of ProsthodonticsDokument1 SeitePreface To The Eighth Edition: The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry The Academy of Prosthodonticsdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- FlashDokument1 SeiteFlashdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Organizations Participating in The Eighth Edition of The Glossary of Prosthodontic TermsDokument1 SeiteOrganizations Participating in The Eighth Edition of The Glossary of Prosthodontic Termsdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Retraction Notice of Temporomandibular Disorders in Relation To Female Reproductive Hormones: A Literature ReviewDokument1 SeiteRetraction Notice of Temporomandibular Disorders in Relation To Female Reproductive Hormones: A Literature Reviewdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Week Planner: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday FridayDokument1 Seite6 Week Planner: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Fridaydrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Abstract Form 2000 I A DRDokument1 SeiteAbstract Form 2000 I A DRdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Help RotDokument3 SeitenHelp Rotdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- 0309 - Kwantlen 4RDokument2 Seiten0309 - Kwantlen 4Rdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- C38 OrofacialDokument2 SeitenC38 Orofacialdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Palatal Obturator: Corresponding AuthorDokument4 SeitenPalatal Obturator: Corresponding Authordrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- 8 2Dokument1 Seite8 2drgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- 26 Pontics & RidgeDokument1 Seite26 Pontics & Ridgedrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- 01 10 005 ReadingsystemDokument2 Seiten01 10 005 Readingsystemdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Flow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceDokument6 SeitenFlow The Psychology of Optimal ExperienceJdalliXNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gray Sample ImageDokument1 SeiteGray Sample Imagedrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Smile Analysis (2) - 2Dokument1 SeiteSmile Analysis (2) - 2drgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Pdi 1413033369 PDFDokument1 SeitePdi 1413033369 PDFdrgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- Zarb 1998 The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1Dokument1 SeiteZarb 1998 The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 1drgayen6042Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- SGT PDFDokument383 SeitenSGT PDFDushyanthkumar DasariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hope Hospital Self Assessment ToolkitDokument120 SeitenHope Hospital Self Assessment Toolkitcxz4321Noch keine Bewertungen

- Leather & Polymer - Lec01.2k11Dokument11 SeitenLeather & Polymer - Lec01.2k11Anik AlamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chewable: Buy Pepcid AC Packages, Get Pepcid AC 18'sDokument2 SeitenChewable: Buy Pepcid AC Packages, Get Pepcid AC 18'sMahemoud MoustafaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BMJ 40 13Dokument8 SeitenBMJ 40 13Alvin JiwonoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Recruitement Process - Siemens - Sneha Waman Kadam S200030047 PDFDokument7 SeitenRecruitement Process - Siemens - Sneha Waman Kadam S200030047 PDFSneha KadamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter Three Liquid Piping SystemDokument51 SeitenChapter Three Liquid Piping SystemMelaku TamiratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ventricular Septal DefectDokument8 SeitenVentricular Septal DefectWidelmark FarrelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Talent MonitorDokument30 SeitenGlobal Talent Monitornitinsoni807359Noch keine Bewertungen

- Penilaian Akhir TahunDokument4 SeitenPenilaian Akhir TahunRestu Suci UtamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dungeon World ConversionDokument5 SeitenDungeon World ConversionJosephLouisNadeauNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soal UAS Bahasa Inggris 2015/2016: Read The Text Carefully! Cold Comfort TeaDokument5 SeitenSoal UAS Bahasa Inggris 2015/2016: Read The Text Carefully! Cold Comfort TeaAstrid AlifkalailaNoch keine Bewertungen

- QA-QC TPL of Ecube LabDokument1 SeiteQA-QC TPL of Ecube LabManash Protim GogoiNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Case - Lijjat PapadDokument16 SeitenThe Case - Lijjat Papadganesh572Noch keine Bewertungen

- How To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFDokument1 SeiteHow To Do Banana Milk - Google Search PDFyeetyourassouttamawayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en InglesDokument2 SeitenParche CRP 65 - Ficha Técnica - en IngleserwinvillarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laboratory Cold ChainDokument22 SeitenLaboratory Cold ChainEmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Women and ViolenceDokument8 SeitenWomen and ViolenceStyrich Nyl AbayonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Renal Failure in The Intensive Care Unit: Steven D. Weisbord, M.D., M.Sc. and Paul M. Palevsky, M.DDokument12 SeitenAcute Renal Failure in The Intensive Care Unit: Steven D. Weisbord, M.D., M.Sc. and Paul M. Palevsky, M.Dkerm6991Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comprehensive Safe Hospital FrameworkDokument12 SeitenComprehensive Safe Hospital FrameworkEbby OktaviaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArticleDokument5 SeitenArticleJordi Sumoy PifarréNoch keine Bewertungen

- Congenital Flexural Deformity in CalfDokument6 SeitenCongenital Flexural Deformity in CalfBibek SutradharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revision Ror The First TermDokument29 SeitenRevision Ror The First TermNguyễn MinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- List of 100 New English Words and MeaningsDokument5 SeitenList of 100 New English Words and MeaningsNenad AngelovskiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pe 3 Syllabus - GymnasticsDokument7 SeitenPe 3 Syllabus - GymnasticsLOUISE DOROTHY PARAISO100% (1)

- J130KDokument6 SeitenJ130KBelkisa ŠaćiriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Valve Material SpecificationDokument397 SeitenValve Material Specificationkaruna34680% (5)

- Service Bulletins For Engine Model I0360kb.3Dokument6 SeitenService Bulletins For Engine Model I0360kb.3Randy Johel Cova FlórezNoch keine Bewertungen

- FINAL PAPER Marketing Plan For Rainbow Air PurifierDokument12 SeitenFINAL PAPER Marketing Plan For Rainbow Air PurifierMohola Tebello Griffith100% (1)

- Soil SSCDokument11 SeitenSoil SSCvkjha623477Noch keine Bewertungen