Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Archaeology in The Andes

Hochgeladen von

Adan Choqque Arce0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

11 Ansichten2 SeitenAdan choqque arce and Alexander SICOS ANCCO study the landscape in the construction of funerary structures. They argue that the landscape has double dimension: material and conceptual reality. For us the landscape is being treated as a built environment: cognitive, symbolic, and (then) physically.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Archaeology in the Andes

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenAdan choqque arce and Alexander SICOS ANCCO study the landscape in the construction of funerary structures. They argue that the landscape has double dimension: material and conceptual reality. For us the landscape is being treated as a built environment: cognitive, symbolic, and (then) physically.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

11 Ansichten2 SeitenArchaeology in The Andes

Hochgeladen von

Adan Choqque ArceAdan choqque arce and Alexander SICOS ANCCO study the landscape in the construction of funerary structures. They argue that the landscape has double dimension: material and conceptual reality. For us the landscape is being treated as a built environment: cognitive, symbolic, and (then) physically.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 2

LANDSCAPE IMPLICATIONS IN THE CONSTRUCTION OF FUNERARY STRUCTURES

Approaches from Tantanamarka Site in P'isaq, Southern Peru

[Implicancias del paisaje en la construccin de estructuras funerarias. Aproximaciones desde el sitio de

Tantanamarka, Pisaq, Cusco. 2010]

Adan CHOQQUE ARCE & Alexander J. SICOS ANCCO

Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco

[Unpublished document]

Abstract

To understand the man's past it is vital the understandingof places, delving into the connections

established between the human being and the space in which it operates, being observed traces of a

complex cultural and social plot, showing the different ways of human thinking and the relationships with

their environment, turned in a humanized space: landscape.

The landscape, though it had become a focus for archaeology, has been treated for a long time from an

economic perspective, considered as a space from where resources have been obtained to survive. It has

been understood as a simple passive scenario and static scene of human alterations. Nevertheless, for us

the landscape has double dimension: material or objective and conceptual or perceived reality, to the

extent that it is being treated as a built environment: cognitive, symbolic, and (then) physically,

constituting an active agent of communicationas a result of constant and dynamic interaction between

man and his environment.

In this way, we speak about the organization of the funerary space that meets standards todefined

schemas of an specific cultural period, within which converged aesthetic, functional and symbolic factors,

by taking advantage of the special physical characteristics such as natural rock cavities and / or modifying

others, which is referred as thelandscape of the deathorfunerary landscape, and it isknown as the "locus

of memory".

With respect to the landscape as an active agent of communication, since immemorial times the Andean

landscape has been alive, personified, and a form of this it is that the burial site may be considered as a

place of ancient mythological originthat the community has a concept of returning of the dead" and

buried to the birthplace which is assimilated to a mountain. Additionally, it has an importance: most of

the funerary structures are oriented towards theEast or a sacred mountain.So, the landscape is understood

as a dynamic and complex synthesis, while it results from the interaction of socio-cultural and natural,

material and conceptual elements, the past and the present:

1. The societies located throughout the Central Andes Mountain range have shared similar

characteristic in termsof the distribution of the funerary structures located in rocky slopes and

headlands.

2. The funerary landscape of P'isaq became a place where the living ones cohabited

withthedeadones, displaying a well-defined territorial ordering, both by natural elements such as

engineering works (walls).

3. It was believed that the person at death did not die, but went to another dimension of life,

returning to the place he had been born (paqarina) like their ancestors.

4. Their funerary constructions were located mostly in hillsides, due to their beliefs and

cosmovision, according to which to the being buried there the deceasedcould guard and ensure

their offspring (ayllu) and the community of the living ones would be close to their ancestors.

adanchoqque@gmail.com

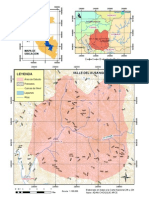

ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE IN THE AUSANGATE VALLEY

Threats of Irreparable Destruction

Will we destroy our heritage and erase our cultural identity?

Adan CHOQQUE ARCE

Universidad Nacional de San Antonio Abad del Cusco

Cusco, Peru, 2009

[Online published]

http://www.monografias.com/trabajos-pdf4/patrimonio-arqueologico-valle-del-ausangate/patrimonio-

arqueologico-valle-del-ausangate.pdf

Abstract

Ausangate valley is located in the foothills of the Mount of the same name, near to Vilcanota River.

Politically, the valley comprises the districts and part of Checacupe and Pitumarca in the province of

Canchis, southeast of the Cusco region, Peru. This valley was in the past and is now a suitable place for

human habitation, for special environmental features it has. According to archaeological investigations it

is constituted with evidences as pre-Hispanic hydraulic channels, human bones, enclosures, platforms,

ceremonial spaces and roads, showing continuous occupation from the Late Intermediate Period to Late

Horizon (Inka), and its representative archaeological site is Machu-Pitumarka.

A society to be such must have something to define itself: a common past, heritage, a shared interest, an

identity that strengthens its values, expressed in intangible culture (folklore, traditions, customs, etc.) and

the Material ones, which are works produced by the human hand, or in combination with nature; these are

capital assets with an intrinsic cultural character. In these lines we do not reference sanctions against

breaches on this heritage, embodied in international charters and conventions, rules or laws protecting the

Cultural Heritage. We discuss what happens daily at the sight of all: An unfortunate reality with the

gradual loss of archaeological elements and evidence.

The major problems are, (1) looting of archaeological sites, commonly known as huaqueo(in Quechua),

with the consequent clandestine trade of their pieces, and (2) acts of vandalism, a tendency to devastate

and destroy archaeological materials.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Lesson Guide 2.2 Beware of Banking FeesDokument4 SeitenLesson Guide 2.2 Beware of Banking FeesKent TiclavilcaNoch keine Bewertungen

- (DOH HPB) PA5 Playbook - Peer Support Groups For The YouthDokument88 Seiten(DOH HPB) PA5 Playbook - Peer Support Groups For The YouthKaren Jardeleza Quejano100% (1)

- Deposition Hugh Burnaby Atkins PDFDokument81 SeitenDeposition Hugh Burnaby Atkins PDFHarry AnnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Method Statement For BlastingDokument11 SeitenMethod Statement For BlastingTharaka Darshana50% (2)

- Handbook of Inca Mythology - Río VilcanotaDokument2 SeitenHandbook of Inca Mythology - Río VilcanotaAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of Inca Mythology - MountainsDokument3 SeitenHandbook of Inca Mythology - MountainsAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Handbook of Inca Mythology - Petrificación y PururaucaDokument3 SeitenHandbook of Inca Mythology - Petrificación y PururaucaAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- UbicacionDokument1 SeiteUbicacionAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sun & Moon Above & BeyondDokument1 SeiteSun & Moon Above & BeyondAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Valle Del AusangateDokument1 SeiteValle Del AusangateAdan Choqque ArceNoch keine Bewertungen

- ArcGIS10 ManualDokument83 SeitenArcGIS10 ManualJuan Delfor Caceres TejadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scope PED 97 23 EGDokument54 SeitenScope PED 97 23 EGpham hoang quanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sacred Scrolls - 29-32Dokument9 SeitenSacred Scrolls - 29-32Wal EldamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapters Particulars Page NoDokument48 SeitenChapters Particulars Page NoKuldeep ChauhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Impact of Broken Homes On Academic PDokument40 SeitenThe Impact of Broken Homes On Academic PWilliam ObengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bjorkman Teaching 2016 PDFDokument121 SeitenBjorkman Teaching 2016 PDFPaula MidãoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mo. 5Dokument13 SeitenMo. 5Mae-maeGarmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Problems On Financial AssetsDokument1 SeiteProblems On Financial AssetsNhajNoch keine Bewertungen

- SBR BPP Textbook 2019Dokument905 SeitenSBR BPP Textbook 2019MirelaPacaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Majestic Writings of Promised Messiah (As) in View of Some Renowned Muslim Scholars by Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (Ra)Dokument56 SeitenMajestic Writings of Promised Messiah (As) in View of Some Renowned Muslim Scholars by Hazrat Mirza Tahir Ahmad (Ra)Haseeb AhmadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jataka Tales: Stories of Buddhas Previous LivesDokument12 SeitenJataka Tales: Stories of Buddhas Previous LivesTindungan DaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Key Insurance Terms - Clements Worldwide - Expat Insurance SpecialistDokument12 SeitenKey Insurance Terms - Clements Worldwide - Expat Insurance Specialist91651sgd54sNoch keine Bewertungen

- Boat Bassheads 950v2 1feb 2023Dokument1 SeiteBoat Bassheads 950v2 1feb 2023Ranjan ThegreatNoch keine Bewertungen

- BLGS 2023 03 29 012 Advisory To All DILG and LGU FPs Re - FDP Portal V.3 LGU Users Cluster TrainingDokument3 SeitenBLGS 2023 03 29 012 Advisory To All DILG and LGU FPs Re - FDP Portal V.3 LGU Users Cluster TrainingMuhammad AbutazilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Building Brand Architecture by Prachi VermaDokument3 SeitenBuilding Brand Architecture by Prachi VermaSangeeta RoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Executive SummaryDokument3 SeitenExecutive SummaryyogeshramachandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Incoterms For Beginners 1Dokument4 SeitenIncoterms For Beginners 1Timur OrlovNoch keine Bewertungen

- Additional English - 4th Semester FullDokument48 SeitenAdditional English - 4th Semester FullanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- RemarksDokument1 SeiteRemarksRey Alcera AlejoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Goodyear (Veyance)Dokument308 SeitenGoodyear (Veyance)ZORIANNYEGLNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tapispisan Vs CA: 157950: June 8, 2005: J. Callejo SR: en Banc: DecisionDokument19 SeitenTapispisan Vs CA: 157950: June 8, 2005: J. Callejo SR: en Banc: DecisionApay GrajoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atlas Rutier Romania by Constantin FurtunaDokument4 SeitenAtlas Rutier Romania by Constantin FurtunaAntal DanutzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Josefa V MeralcoDokument1 SeiteJosefa V MeralcoAllen Windel BernabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ba (History)Dokument29 SeitenBa (History)SuryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BTL VĨ Mô Chuyên SâuDokument3 SeitenBTL VĨ Mô Chuyên SâuHuyền LinhNoch keine Bewertungen

- 202 CẶP ĐỒNG NGHĨA TRONG TOEICDokument8 Seiten202 CẶP ĐỒNG NGHĨA TRONG TOEICKim QuyênNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Parties ManualDokument46 SeitenPolitical Parties ManualRaghu Veer YcdNoch keine Bewertungen