Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

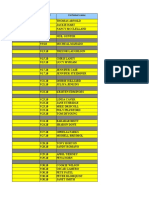

Naphy, WG - 2007 - The Protestant Revolution - From Martin Luther To Martin Luther King JR - London - BBC Books, 23-36-5!2!16-9-17

Hochgeladen von

pragette1Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Naphy, WG - 2007 - The Protestant Revolution - From Martin Luther To Martin Luther King JR - London - BBC Books, 23-36-5!2!16-9-17

Hochgeladen von

pragette1Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

4 i f shame Tar wm.] wml Mmaa .

Europck southeastern llanl; open to liirkish Muslim advances, with the result that thousands ol Christians (Orthodox, Roman Catholic, Lutheran and Calvinistic to name but a lew) fell under Muslim power and, ironically; were lorced to coexist. Moreover, this religious rivalry and denominational competition was exported around the world and became a lactor in gl '] European global competition in the opening phase of Europe's first `push i for empire'. Spaniards and Portuguese spread Catholicism in the east; Dutch Calvinists undermined ]esuit missions in ]apan; British Protestants l and French Catholics liought for dominance in North America. VVhether or not Luther's hammer ever struck a blow in VVittenherg is l l F L E G E N D C A N B E B E I. I E VE D , T H E P Rl ES T A N D unimportant . VVithin a century blows were being exchanged across Europe, theologian Martin Luther nailed a set otwquestions lor debate (in Latin) to a nd Christianity hegan to crusade against itselii More than at any time in lf the doors 0lVVittenherg church on g 1 October rg 1 7. His intention was to the past, states and churches, ministers and magistrates, priests and politiii advertise a university dispute about a series of debating points, ninetyiive ciarrs became almost obsessed with the beliefs of individuals. VVhat people in total, and consequently referred to as Luthers Ninetydive Theses. He belie ved - not what they did could get them killed. And yet, more than was concerned about practices that he considered inappropriate: the way in at any time in the past, peoples ability to think, question and decide relil 1 which the Church was raising funds (in part to Hnance the rebuilding of the gion for themselves became easier and more common. By the midsevenl Vatican hasilica, the presentday St Peters). Beyond provoking a lively theoteenth century it seemed as though almost everyone in Europe had picked logical and ecclesiastical debate at the university; it is not immediately cle ar up a hammer and was nailing theses on to every door, wall or tree they li what Luther hoped t0 accomplish. VVhat is clear is that he had no intention could find. How this accidental revolution happened, and its impact on the of sparking a revolution and of breaking apart V\/estern Christianity But that way the West thought and acted is fundamental to understanding how the is what he did. modem world came into existence. One thing, though, is certain lrom the l Less than a century and a half later, by 16;::, much ot Europe had been outset . it Luther had seen where his theses would lead, he would almost comulsed by wars about religion as a result of Lut;hers `accidental rev0lu certain ly have hammered his head rather than the nail. . tion. Hundreds 0t thousands of people had died, towns had been laid However, any discussion of the Reformation, Luther, and what Followed waste, disease and {amine had stalked the land. Armies had marched from must b egin over a century belore V/ittenberg, Prom the late fourteenth Spain and italy in the south, from Sweden in the north, across ireland and cen tury throughout the litteenth century the late medieval, Western Church Poland and the Czech Republic and Hungary Monarchs had lost thrones was the sc ene ofealls lor reform. Some were dramatic, others less so. Most and, in one spectacular case (Charles I of Great Britain), their heads. were r msueeessful, but left an indelihle stamp on the mindset ofthe Church EUFOPGHI1 lroreigll p0liC}' was tl'110\\`U intl) <liSHI`1`6}' Catholic l:r1C timded a its parishioners. At some level and to sornc extent most Christians iii Protestant armies and Calvinist Hungarians looked to the Turkish sultan to Western Europe mere, hy 1 gem, very well aware that things needed to ll protect their ireedom ol worship, Indeed, the conflicts lctt Christian Chang e, and that change was heing demanded from above and below As WB I l

l { if 2

ii, c1i.a1Tyk0mi sowist, nit wisn wrin itrroitn we shall see, though, the `changes' that were being mootcd were very different stru cture and government of the Church, and it was largely motivated by from what Luther actually set in motion Arid VVl\3[ VHl.ll3lly tfmfgeil. a desire to resolve a specific problem (multiple popes), ilivo other rn0v<` Real problems arose and with them calls for rcfornn in the late llour- ments, t hough, with entirely diflerent motivations and goals, arose at the tcenth century when different nations in Europe recognized, in 1378, two same time. The first appeared in England in the 1g8os, when the philosodifferent popes. One was based in Avignon (accepted primarily by France, as ph er and theologian ]ohn W'yclif began to call lor a Church that was ill l well as by Spain and Scotland) and the other at Rottie (backed hy the Holy humble and poor. He was particularly incensed hy ecclesiastical wealth in I Roman Empire, England and most Italian states). Urban VI and Clement VI] hoth land and linery (the gold, silver, jewels and ornamentation seen in posed a difficult problem for Western Christianity V\/'ith a strong theologica l churches), though he was not so offended as to give up his well-paid posts ll commitment to papal supremacy (the idea that the pope, as successor to St i n the Church. He also believed that the Bible should he placed in the Peter, was head of the Church), Christianity now had two heads - in this hands ol ordinary Christians, and that it was the standard against which I case, definitely not better than one. This was clearly a situation that req uired doctrine and practice should he checked. Opponents called him and his immediate resolution, hut there was no mechanism for doing so. Nery followers l.ollarils (probably from the Dutch lollacrd, `a muml>lcr') since j quickly; though, leading churchmen and scholars began to call for a general they spoke nonsense', In the end, Lollardy was suppressed ancl. interestcouncil (a gathering of leading clergvmen and theologians). This council ingl} ; hnglish Church officials hannetl all English-language versions ofthe would constitute a 'suprerne legislative hody capable of sorting out the Bible, Although a sensation at the time, especially in England, die Il\0\'t` jl number of popes and any other matters that might arise. ln effect, it was th e ment met with little success, and rather quickly faded into the background. first step towards producing a system ofcheclcs and balances, and giving the I t did, however, throw into stark relief the question not only of the Bible, 1 Church a government. This was Lhe conciliarist movement. hut also of its lang uage. The first serious attempt to use a council to setde the issue of multiple The second major movement to arise during thc Great Schism was popes was the Council ofPisa, which, in 1409, simply clccted a third pope. co nsiderahly more successful and had a lasting impact in central Europe. Fortunately for the Western Church, the next council, meeting at VK/yclifils i deas spread, rather hixarrely as a result offoreigmpoliq ties, flroni Constance in Switzerland, was more successful. It deposed two of the England t o Bohemia (in the modern Czech Republic) and had an impact on popes, accepted the abdication ofa third, and elected Martin V as the single t he preacher ]an Hus at Prague University Hus and his followers, flussites, ll new pope. This ended the Great Scliism in the West, as well as the so-called were much more successful than \Vyclif in that their ideas became linked L `BalJyl0nian Capti\ity (papal residency in Mignon). It also ended concil- with ethnicity (an important issue in explaining the success ofsome reforlb iarism. Martin V and subsequent popes showed no interest in erecting a mation s, to which we shall return). As a Czech-speaking movement, Hussism system of `c0nstituti0nal' government for the Church, much less bring-ing Provided an epicentre for resistance to German-speakers. Hus also attacked

it in checks and balances on papal power, and accepting the supremaq oi the wea lth of the Church and highlighted many other areas of perceived dI1y0H or Anytlling (Such as 3 Council) over them. However, this did set an abu ses, especially among the clergy Hus became su SuCCSSilUl that he WHS il1l'StiHg prC<lClit, and during the Reformation meant that councils summoned to the Council of Constance (which would elect Martin V and Wf Oilln seen AS A means of resolving the debates sweeping the Church. end the Gr eat Schism) to explain his ideas. He Was provided with A SHf l Conciliarism was not the only reform movement. Its focus was on the conduct hy the Holy Roman Emperor. Sadly; this availed him not at all, and ,l llc; 2 A t CHAPTIK UNL $O/[NG 'Il{} VVINU \\'1'IH Rl\()KM ji the Council finally sealed the end of the schism with Hus's hlvfld IW WAS with C vnstrudillg an entirely diffbrent type of society eommunity and way burnt at the Stake as a h,tjC_ of life thm were distinct and acparatc from the wider community Unlike Lollan-dy though, Hussism did not fade away News of Husk execution was met with fury and violence in Bohemia. His Follow:-rs split, A N EW PI ETY and civil war ensued. Despite {ratricida] innghtiug and cHbrLs by ibrces loyal It would he A mistake, though, to imagine that calls for, or avmrcncss ofthe m Rome, Hussism survived in two predominant forms. The Utraquists, of need fm, reform came solely from the mp levels of society or a few learned whom there were two types, were the less radical version, Iargelyrusembling th eologians and their followem. Indeed, in some senses reform was well the Roman Church except in two key areas. First, they worshipped in the under way by the time of Luther, and was almost A mass movement. Tivo vernacular, the language ofthe people; second, the common people received spec ific examples will suffice for the genera] trend. The Hrst was the devvnm both the bread and the wine at Communion (hence their name - fron) maderna (ne w devotion ur new piety) and the second was humanism. In uzmquc, Each of {wd). The norm elsewhere was hr the broad to be given to their mm way these two nmvcmcms were changing not only the way people AU, but the wine to be taken only by the celebrating priest. The more radi- th ought about religion and their church, but also the way in which they ca] variety of Hussism, the Union of Bohemian Brethren (Umm; Fmt;-um) practise d their faith and worshipped their God. The changes were sion; E Shared these views, but went well beyond them. The Brethren rejegrml the oft en minimal and usually seemingly inconsequential. Cumulativcly, Y notion of transubstantiation that the bread and wine became the body and how ever, these two movements [aid much of the groundwork for what blood 0f Christ. They also denied any concept of an priesthood separate: from would follow in the Rcnyrrnation. the rcst of the bclieving community (in effect, they held to a pncsthood of Th e Jcvatin nmdenm began in Holland during the late rgom (in many allbclicvcrs). Theyalsobclicved that the Christianity ofthe earlyChurch and wa ys in the aftermath ot; and in response to, the Black Death and the the New Testament called tbr a radical separation from general society and, su bsequent bouts of epidemic plague) and spread across the Low especially; the State. They also stressed Christs instruction tu `tum the other Countries, German); France and parts of Italy The movement, with its ~1 check. They therefore opposed all fbrms of violence, capital punishnqent, emphasis on the supposed original simplicity of the early Church and its N military service and taking oaths (includiugin cuurmmms). faith, appealed 10 "F

lay people and clerics alike. Clergv responded to the Many 0{ thcsc issues will bc highlighted in thu story 0{thc Refbrmatiou m0ven1 cm's cal] Har .1 more holy; devout life by keeping the vows they had that follows. The most important point {0 grasp at this point, though, is that taken. Lay people were especially attracted by im emphasis upon an il'\l\|' by 1 500 there was il part of Europe that was almady beyond the control of dev otional lik, apart hom (though often complementing) thc Churchk Rome. Not only was there an established, H.1llCtiOl"IiIlg Ibrm of Christianity institutional means of salvation (for example, the sacraments ofthe Mass or that rejected the papacy before Luthcr, but, in Bohemia, there were actually e xtreme unction A the last rites). VVith between a third and halfofall clergy I two varieties. These two, as wc shall sect, were fbrctastcs of the features o f dying during the plagues of the last half of this fourteenth century; these Protestantism set to emerge in the course of dm 1 goes. The Utraquigts were in stitutional means were considerably lash available, and in somc parishes a structured church (denomination in the modern sense) very similar in lay peo ple were largely left to their own resources. hierarchy; worship and theology with Rome, but rejecting papal mmml, The Adher emg (perhaps bcctcr described as exponents) of the demrio Brethren were Icss intcrcxtcd in thenlogv and considerably more conccrncd mude ma also tuck to heart many of the more thenlogically orientated ideas M ; ;:;2~ tilt; El"; CHAI-'TIR 0Nk \(I\\'1N(&T1lE VVINI) VVITH ll|lOI<!I i ofthe period, Thus, purely external and superficial acts of formulaic piety best~surydving window into this new; personal type of religiosity and piety and devotion were criticized. Likewise, many asserted, as torcehilly as is the Imitation q]Christ by Thomas 21 Kempis from Cologne. During this jh Luther would do early in the Reforniation, that God could be understood per iod, though, other works were also important, for example, the Spiritual not only by scholariy theologians. but also by the humblest peasant. The pig cennunr hy Gerhard Zcrbolt, a priest and librarian at Radeuijifs founda catastrophic pwchological impact of the Black Death also brought to the tion i n Deveriter. Indeed, his work was certainly read by Luther, though it fore an appreciation of the mortality and sinfulness of all mankind (surely is impossible to say with certainty that he or any other reformer was heav(l., God was striking his people with plague for their sins) and the urgent nee d ily or directly influenced by the demrio mndemu. However, what can be said for salvation. is that many lay people, especially in northern Europe, were in fluenced by However, this movement did not lead to a call for a change to the struc- the movement and, as a result, favourably inclined to types of religion that tures of the Church: rather, it was a plea tor all individuals to take a inore placed an emphasis upon personal and indixddual piety; and a more direct active part in the devotional life of the Church and its worship, ln particu relationship with the divine. l lar, and in stark contrast with later reformers, exponents of the Jcmriu I modema often stressed the intimate and mediating nature of the sacrament H U MAN l SM ofthe Mass when adored or taken by a Christian. Great stress was also laid V \/hile the Jewrio modema had an important impact on the practice of reli lf on the physical sufferings of Christ (and, at times, his mother the Virgin g ion in much of Europe, humanism had a much greater influence, espeMary) and his victory over them all the more critical and poignant for a ciall y in the understanding of religion. Beginning in Italy during the society piling its dead into plague pits (like `ldSJgliC,, as the Italians noted

) Renaissance, humanism placed its emphasis on rediscovering the culture ji) in their thousands. of the ancient world, ln particular, this meant revivin g classical Latin, The movement arose in the Low Countries, with Geert de Groote as a encouraging a familiarity with Greek and, in the context of religion, placing key figure. He was not a priest, but was licensed to preach (in and around a s imilar importance on a knowledge of Hebrew This new learning, ill Utrecht), although his licence was eventually revoked because of his `humane letters as it was called, was in contrast t0 medieval scholasticism sermonic attacks on clerical abuses. The movement attracted much lay (sacred letters), which stressed philosophical and theological exactitude. support, and this became more or less organized into the Brethren of the This contrast and critique is best exemplified by the humanists jibe ai Common Life. The Brethren were associations (sometimes sharing accom- (entir ely unfounded) that scholasticism had become so obtuse that adher} modation) of lay people, including women, and `secular' priests (those who ents might spend hours arguing about how many angels could dance on the were not monks). The communities were often semi-monastic in style, but head o f a pin, Humanism was, therefore, a new way of thinking about the never wholly cut off from the world. A monastic version did develop among past , a new way of reading documents, a new way of expressing oneself the Windesheim Canons (founded 1387) under Florentius Radewijns. (normally in `c orrect' Ciceronian Latin). il} However, the movement was most successful in its impact on the way ln some cases, this new emphasis upon Latin, classical learning and in which lay people actually worshipped, and the types of piety they ancient c ulture became almost slavish, if not actually pagan. The poet Dante if displayed. It was both intensely personal and explicitly secular in its dete r Alighieri, fortunately lor Italian, decided (only just) not to compose his mination that the new devotion would be imbedded in `this world`, The Inferno in L atin, His iellow poet Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) saw some of J so a i * i `lll ii,] l invvmr, ini ws., min srinan 1. . . iii, ansi-rtit osiEli i iii; _ .___\, V, _ . _ _ V his Own Works as an attempt to rival the Cicgam Latin Oi Virgiys Acm,ii]_ Au excellent example ol this disdain for institutional reform is the Bin _ , , . . ~ ,_., - V. . , ., ., t lg?] Many authors opened their literary works not 0nly with invocations of l1m>` Qian l'V<m<*><* Peggie, A H $~FLY*}. lik M U>mP1l (YN MU-) il _ _ _ , , _ . _. - 7. , _ _ i like l hrist but also a an deities or the muses. Ior Italians es memlly; liuingui - P<Jpe ]0lm XXIII to tht Count il of (nnstante (the ont that burnt Hus)_ ii, i P E l . _ ism was c cttin in muciy with their aiiL.CSt0i.S_ The, Wei-C Sim iv ciiiiin , Instead oil concentrating on the counLils delilierations, hc spent much ol ig E E , P . 3 _ { ig ,j" Oi-ei the Middle A CS in- the Dark A es liumimisi {gms [hai yiyc (iii i iim Of his time hrowsing the liliraries ol the monasteries in thc area and borro wii S S 5 gf, E what il-my tlmiight ofthe Cciitui-ies imm(]iatE]y [whim] them), miii Piugi iiii ing (permanently} their most valuable works. Ib the extent that he noticed

V back intl) tlltflf greater cultural past. Consequently; Italian humnnigts wo uld Hus and l\lS COl1`iD3Ul0DS, lic was largely positive and tleplored their pe1`s<y speak of Caesar as `one of us and Hannibal as a `lnrgigmgr_ cution. The hulk 0i t his papal secretary's life epitomized Italian humanism. ' . . . , A . in ari, humanism and the i{,;.nai5sanC aiiied io return to thc {OHDS ami He xx rote in Latin and spent much of his lite deciphering, copying and edit l"l aesthetics ol the ancient world. The sensuality and inrlced styini- wrnnqmin Y mwlj <list<>vtrcd Latin and Gi ttlv manuscripts. Ht xv as also an artlutY i i . > l rs :l . . .. . . . * .,: Y ,- 4. . . ., . 'i . i, e hv ol some Renaissance art evokes this s irit. lt is erha s interestin to ('l ",1Sl 5P@U3ll} my Romhle Yl Hs ma} hm dPl"rd mu'~h <>**~l1l< r P , P P P g fi; Spqnnlatc how 3 ggqiety Sn Cnylinsjasncally rhmwing Off its nwrligval (and saw in the Church as <>l<l-iashmued and hypocritical, but he seems to have Christian herita e was so immune to the call ot Luther and other reibrm gisen l ittle thought or concern to more substantive problems, such as what ti ~ 3 I ers. Equally one cannot help but note that the almost hedonism- mvnlrv nas h eliued or hou Faith was to be hud. i in classical culture was considerably less a feature of the Renaisgamge in I talian humanists were simply not interested in reforming the Church. il { , . . . i` northern Europe, where the Reformation would eventually mlm root, l? the ext ent that one can discover any clear religious beliefs, some were ll, lflCl<l, it is perhaps more accurate to suggest that the form gfliunmnism p agan OT SCIHlp3gAU, and Iuany were Deists. They stressed the attainment lll most important to this discussion was the one that placed an gmphngi; upon of perfection in this life, by which they meant not moral pertk-etion, but linguistic analysis of documents and the rediscover)- of the `x;;Cr` in rather lite rary and `social' perfection. Living right meant living well, not C0l`lQCt' Hleanlng ol ancient texts, particularlv the Bible, ll\'il\g Oui YOIUE mor al or spiritual Code. lndeed, l|"lATly were amoral, ii not l" ' . ,. i ii VVllll l1umalSl11 was important it should not be mere5timnte{_l, The 1IHlTl0l'H l by the Sfdntlaflls ol their day (and perhaps, at times, oi the pres heartland of humanism and the Renaissance was Italy; and Italy was largely ent day t00). They disdained the Church, hut were quite happy to take its deall to the Reformation. ltalian humanists did despise clerical abuses and of fice, henelices and pensions. They prelerrcd the sensual pleasures ot Ovid ii _ _ _ . , _ _ l what they considered to he the stupidity of traditional theological debate, to the austere, introspective other-worldhness of the New "lestament. Suite l;_ but at the core otltheir ambivalence to the institutions oil the Church seem s they greatly exceeded the amorality and immorality oi many clergy; they H to have been zi general revulsion at hypocrisy, not hedonigny Italian humancould not take any practical interest in spiritual or theological reformation. lc . . . . , i ) . 4 . _ _ _ _ . _ _ >_ \ ists were not appalled at lavish liwng or pure pleasure. What seems to have Th t great historian lacoh Burcl<ha1<lt has suggested that humanists ncrt aiinoyepl thu-ii was the Pnmposity and hypocrisy of Cleiics Engaging in mi;]-i k((lt`-r)lTlOI`3l1Z('(i) by spending so much time steeptd in the hte ratuie oi A i behaviour, while pretending not to. Italian humanists were not so much |<l<>iS< Pa an Past` . . . . .. ` .. ~ ., V , ..-.`_ li, callin lor reform oi the Churchs morals, as tor lilo to he embraced in thi s H>m m >rth< ' li"OP * 6 m>l* mbl} m(` 5 ' " ~ 1* g .

i . world instead of the next. Had this sort of call been heeded, there would o us and spiritual movement. It would he frivolous to suggest that the cold have been Chan Q_ but ii would not have been it.i},iiiiatiOii_ oil the north ma de hedonistic caxorting a little less attractive (or practical) i g il} i s z i; iz _ { _ t;t illill euapi-rn owr Witisr; rin; wiwn vir1ii<>-Foam than it was in Italy Nevertheless, there was a distinctly different climate to Iznc/vclopaerlia (199) the Iainous `lil.>eral, Catholie theologian loseph Sauer northern European humanism. There was less a feeling that the elassical (,g727 [949) xyrgteg 1 1 world was `their' world and less a desire to rediscover `their' ancestors, The aesthetics of northern humanism focused OH the beauty of H hilly uH(lTe The l iterari works issued hy Erasmus made him the intellectual Stood text and at pleasing translation, not the perfect form ofMichelangel0 s lather ofthe Relormation. What the Reformation destroyed in the = David or an Oviclian crudity amusingly expressed in Ciceronian Latin. organi c lite ofthe Church Erasmus had already openly or covertly Desiderius Erasmus of Rotterdam is the best example of this northern suhxerted in a moral sense [lri]e regarded Scholasticism as the iii style of humanism. He loved classical literature; indeed, his lirst publis hed greatest perversion of the religious spirit; according to him this work (Adagio, r 5 oo) was a collection of Latin and Greek proverbs. He used de generation dated from the primitive Christological controversies, his excellent command of Latin (for example, in igoz in his Encbiridion xxhieh caused the Church to lose its exangelical simplicity and /lI1Iitis Chrittiam -7 Manual of :1 Christian Knight/lilizrriarr) repeatedly to become the victim ollliainsplitting philosophy [Tliereafter] there lampoon clerical abuses and to call for greater piety and an adherence to appe ared in the Cliurch that Pharisaism which hased righteousness l, true religion. Indeed, in his 1 gag work Encnmium Manne (In Praise <y{F0Ib`), on good works and monastic sanctity and on a ceremonialism he blasted abuses throughout society; especially in the Church. That he bene ath whose weight the Christian spirit was stitletl. Instead of thought this work would cure rather than kill is apparent in its dedication devoting itself to the eternal salvation of souls, Seholasticism repelled to his friend Pope Leo X (Giovanni de Medici). Throughout his life he the relig iously inclined by its hair-splitting metaphysical speculations walked a precarious line between embracing society and lambasting it, and it s over-eurious discussion ofunsolvable mysteries Even his ll Erasmus attacked abuses wherever he saw them, and through his satires concep t ofthe Blessed Iiucharist was quite rationalistie and l` provided much of the vitriolic polemic that wouid he used so eilectively resen ibletl the later teaching of Ulrich Zwingli. Similarly he against the Church by the reformers. Importantly; his more serious writings re jected Confession, the imlissoluhility of marriage, and other provided the intellectual weaponry to assault many ofthe traditional truths fu ndamental principles of Christian lite and the ecclesiastical of the Church. These included The Vlfmlc New Testament (rgi) with notes constit ution. He would replace these [with] the simple words (which were often satirical and biting) and a new Latin translation meant to o f the Scriptures, the interpretation of which should he left to the " replace the Vulgate, and his Pamphmses tjihe New Ykrtumem (1 g 1 7 and later) . individual judgement. The disciplinary ordinances ofthe Church met

ll just as important was his critical reading 0f the books of the New with even less consideration, fasts, pilgrimages, tencration of saints Testament. He questioned the authorship of james the apostle, and the and thei r relies, the praiers ofthe Breviar); celihaq; and religious epistles to the Ephesians and the Hebrews. He approaclied the biblical texts o rders in general he classed among the perversities of a formalistin fl; with a cold rationalism, and treated them no differently than he (or any Sc holasticism. Otter against this `holiness of good works" he set the other humanist) would treat any other ancient document. `philosophy of Cluist', a p ureh natural ethical ideal, guided by The role that Erasmus played (while remaining loyal to the Church) in human [w istloni]. or course this natural standard ofmorals V~ the later Relbrmation and the establishment ofa `modern view of religion oli literatetl almost entirely all clifferences lietween heathen and is best expressed in a hardly supportive evaluation. In the Catholic Christian morality, so that Erasmus could speak with perfect v l sa ss gs I; I ClI\Pi"i:R UNIX seriousness of a `Saint Virgil or a Saint Horace In his edition oil , I the Greek New Testament and in his `Pai`aphrascs' he , I I [foreshaclowedj Lhc Protestant view of the Scripttires. , 1 Erasmus, rather to his horror, proiided the reformers with tht- ammunition I both cerebral and vicious to attack, wound and tear asunder the hodv of _ _ _ , _ ,_ _ H _ ,_ _ _ _ _, ,_ _ _ I . T, t . ; e w e r w ; z v will I Christ the Church sa t ei. I Tx ch I ri is ; i I Q 5 2 I i is \~ is 2 ' : And yet Erasmus was no Protestant. He not only wrote that `Luthers F P gt Q % E A//1 ii}: I movement was not connected with learning] but also that he could `iind a _ V __,, .. V A hundred passages where St Paul seems to teach the doctrines which [are TI . condemned] in Luthcrh Most importantly he rejected and abhorred the T H I S MO 5 T M I S E RA B I- E A N A RC H Y C AU 5 E S chaos that seemed to follow in Luthcr's wake: `I would rather see things left M E 3 U C H A N G U T g H T H AT I WO U Tr T) rj, LA D LY as they are than to see a revolution that may lead to one knows not what L E AV E .,, H , S L, F E A N A RC H Y S T RE N G T H E N 5 f" the pithicst description and warning oi the results ot l.uthcrs accidental I I A , revolution. Much of his lil-e's work was taken and shaped, in the hands of T H E P RE S U M PT I O N O F T H E W I C KE D A N D lgi reformers, into a hat with which to heat the Church. Erasmus des eratelv T H E N E G L E CT O F I EA RN I N G T H R E AT E N S T, P . desired reformation in the Church, the key word for him being `in. The TO B Rl N O O N A N OT H Tg R AG E O F D A R KN E S S status quo was bad, hut schism was worse. Schism, however, is what he got. A N D O F B A R BA RI S M C O N TE M PT O F I, RELIGION PARADES QUITE OPENLY. PI>III,II'I' Nl1,tA:<<;iiT|io\1,Tui,oiv>r;iaNxNn II1I,ICATt)R I, hui rtw)

T, 2 hl I ii I I I, Ii" ** D I1, _ I.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Young Women Song LyricsDokument2 SeitenYoung Women Song LyricsEstoni Joy Robles PilloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dangerous Prayers Part 4Dokument18 SeitenDangerous Prayers Part 4cordilia100% (2)

- HinduphobiaDokument64 SeitenHinduphobiaPriya Kenkare100% (1)

- Seeing The Goldsmith's FaceDokument9 SeitenSeeing The Goldsmith's FaceElaine DGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Please, Wash Your Hands: Matthew Series - June 24, 2012Dokument30 SeitenPlease, Wash Your Hands: Matthew Series - June 24, 2012Jenny J. KimNoch keine Bewertungen

- 29 Fr. Sergius Bulgakov in Orthodox HanDokument7 Seiten29 Fr. Sergius Bulgakov in Orthodox HanCladius FrassenNoch keine Bewertungen

- .Islam and OthersDokument405 Seiten.Islam and OthersShemusundeen Muhammad100% (1)

- TRACKER FOR PROCESSING DEP - Xls (Nov. 26 and 29)Dokument1.431 SeitenTRACKER FOR PROCESSING DEP - Xls (Nov. 26 and 29)Jhun LeronNoch keine Bewertungen

- Living and Loving As Disciples of Christ: Scope & SequenceDokument12 SeitenLiving and Loving As Disciples of Christ: Scope & SequenceJOSEPH MONTESNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oratio CyprianiDokument1 SeiteOratio CyprianiJoe DickersonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Why Christians Should Support Israel PDFDokument161 SeitenWhy Christians Should Support Israel PDFRuth Ramirez100% (1)

- 7 Last WordsDokument4 Seiten7 Last Wordselexis26Noch keine Bewertungen

- Prayer Devotional and Lord's Supper Guide - April 2013Dokument2 SeitenPrayer Devotional and Lord's Supper Guide - April 2013Karina Laksamana AlvarezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Corinthians SampleDokument79 Seiten1 Corinthians SampleGelci Andre Colli50% (2)

- Women in The Fourth Gospel and The Role of Women in The Contemporary Church - Schneiders, SandraDokument12 SeitenWomen in The Fourth Gospel and The Role of Women in The Contemporary Church - Schneiders, SandraEnrique VeraNoch keine Bewertungen

- CCF Sunday Service 05262019Dokument2 SeitenCCF Sunday Service 05262019DongkaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sermon On Galatians 6: 1-6Dokument3 SeitenSermon On Galatians 6: 1-6Ebenezer GangmeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Christianity BTh.3BDokument33 SeitenHistory of Christianity BTh.3BMuhammad QamruddeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- 0330-0395, Gregorius Nyssenus, Against Apollinarius, enDokument62 Seiten0330-0395, Gregorius Nyssenus, Against Apollinarius, en123KalimeroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Church Programs Camp MeetingDokument2 SeitenChurch Programs Camp MeetingAllen M MubitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Calendars: Benedictine and Roman GeneralDokument8 SeitenCalendars: Benedictine and Roman GeneralAlban RileyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Radiant I Am - Emma Curtis HopkinsDokument14 SeitenThe Radiant I Am - Emma Curtis Hopkinstruepotentialz100% (4)

- Recent Theological Opinion On Infused Contemplation: Robert B. Eiten, S.J. St. Mary'S College St. Mary S, KansasDokument12 SeitenRecent Theological Opinion On Infused Contemplation: Robert B. Eiten, S.J. St. Mary'S College St. Mary S, KansasphlsmobyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ce1 Module 7Dokument5 SeitenCe1 Module 7Charis RebanalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beyond The Suffering SubjectDokument16 SeitenBeyond The Suffering SubjectJack BoultonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tab Lesson08 Answer PDFDokument2 SeitenTab Lesson08 Answer PDFAdam Anthony NyamarunguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Who Are The Creation 7th Day Adventists?Dokument7 SeitenWho Are The Creation 7th Day Adventists?JirehielNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dogmatic Theology - IX - The Sacraments (02) - Pohle - Preuss - OCRDokument416 SeitenDogmatic Theology - IX - The Sacraments (02) - Pohle - Preuss - OCRIohananOneFourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Altar Counselor's GuideDokument16 SeitenAltar Counselor's GuideJohann JordaanNoch keine Bewertungen

- ParaklesisDokument23 SeitenParaklesisDiana ObeidNoch keine Bewertungen