Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Guest Knight Dissertation - 9-14-09

Hochgeladen von

Glenn E. Malone, Ed.D.0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

974 Ansichten89 SeitenDr. Knight on Student Voice

Originaltitel

Guest ~ Knight Dissertation - 9-14-09

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenDr. Knight on Student Voice

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

974 Ansichten89 SeitenGuest Knight Dissertation - 9-14-09

Hochgeladen von

Glenn E. Malone, Ed.D.Dr. Knight on Student Voice

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 89

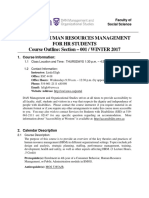

The Use of Student Voice to Inform Communities

of Practice in the Lesson Design Process:

Conclusions for System Leaders Seeking

to Increase Student Engagement

Mark Edward Knight

A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Education

University of Washington

2009

Program Authorized to Offer Degree:

College of Education

University of Washington

Graduate School

This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a doctoral dissertation by

Mark Edward Knight

and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by the final

examining committee have been made.

Chair of the Supervisory Committee:

__________________________________________________________________

Michael A. Copland

Reading Committee:

__________________________________________________________________

Michael A. Copland

__________________________________________________________________

Kathy Kimball

__________________________________________________________________

Stephen Fink

__________________________________________________________________

Steven L Tanimoto

Date:__________________________

In presenting this dissertation in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the doctoral

degree at the University of Washington, I agree that the Library shall make its copies

freely available for inspection. I further agree that extensive copying of the dissertation is

allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with fair use as prescribed in the U.S.

Copyright Law. Requests for copying or reproduction of this dissertation may be referred

to ProQuest Information and Learning, 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-

1346, 1-800-521-0600, or to the author.

Signature _____________________________________

Date ________________________________________

University of Washington

Abstract

The Use of Student Voice to Inform Communities

of Practice in the Lesson Design Process:

Conclusions for System Leaders Seeking

to Increase Student Engagement

Mark Edward Knight

Chair of the Supervisory Committee:

Associate Professor Michael A. Copland

Educational Leadership & Policy Studies

More than ever, our nation is putting pressure on our public schools to ensure that all

students achieve. Unfortunately there is large disconnect between this goal and what

many students are able to demonstrate in terms of their skills and knowledge. What is

often missing from the conversation is that learning is not done by mandate; rather it is

done through a conscious effort by educators to engage students in the material that the

greater community deems important. This type of learning requires a deeper

understanding on the part of teachers about the students that enter their classrooms. It

requires a change in the traditional teacher-student relationship which suggests that

teachers are the experts and students are passive receivers. Instead, students must move

to the forefront and be allowed to have a voice in their education. This places the teacher

in the position of listener and allows them to gain insight into what engages students in

their learning. Therefore, system leaders are faced with the challenge of how to best

provide the capacity for student voice to influence teacher practice so that the end result

is an increase in student engagement and overall achievement. The intent of this action

research study is to look at a small suburban high schools use of student voice in the

lesson design process and how that leads to greater engagement in the classroom.

Through the use of student focus groups, teachers were able to learn about their students

prior to designing classroom activities. Qualitative methods of observations and

interviews were used over a 7-month period of time involving 30 secondary teachers and

38 students in grades 10-12. What was discovered was that students in this process

experienced a high degree of empowerment over the fact that adults were interested in

what they had to say regarding their interests and experiences. While it is too early to tell

if this method leads to an increase in student achievement, overall, the study concluded

that the use of student voice activities in this setting increased the engagement level of

both students and teachers.

i

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

List of Figures....................................................................................................................iii

List of Tables..................................................................................................................... iv

Chapter 1. Engagement and Student Voice........................................................................ 1

Introduction and the Problem of Practice............................................................... 1

The Local Context................................................................................................... 3

Activities Influencing This Project......................................................................... 6

Literature Influencing This Project......................................................................... 9

End Product........................................................................................................... 17

Chapter 2. Inquiry Design................................................................................................. 18

The C4D Proposal................................................................................................. 18

The Student Voice Pilot Project............................................................................ 19

Framing the Problem of Practice.......................................................................... 21

My Location within the Project............................................................................ 26

Chapter 3. Methods........................................................................................................... 28

Type of Study........................................................................................................ 28

Boundaries............................................................................................................ 28

Participants............................................................................................................ 29

Data Collection..................................................................................................... 32

Chapter 4. Making Sense of the Data............................................................................... 35

Personal Observations and the Focus Groups....................................................... 35

Focus Group Preparation...................................................................................... 35

Video Team Story:.................................................................................... 36

Social Studies Team Story 1..................................................................... 42

Group Processing.................................................................................................. 44

Social Studies Team Story 2:.................................................................... 46

Math/English Team Story:........................................................................ 48

Results ................................................................................................................... 53

Chapter 5. Conclusions, Implications, Essential Learnings, and the Future of

Student Voice in the School District..................................................................... 58

Conclusions........................................................................................................... 58

Implications........................................................................................................... 63

Essential Learnings............................................................................................... 66

The Future of Student Voice in the School District.............................................. 68

ii

List of References............................................................................................................. 70

Appendix A. Images of School Chart............................................................................... 73

Appendix B. Interview Focus Groups Administrator Questions................................... 74

Appendix C. Interview Focus Groups Teacher Questions............................................. 75

Appendix D. Interview Focus Groups Student Questions............................................. 76

Appendix E. Parent Permission Letter.............................................................................. 77

Appendix F. Teacher Participation E-Mail ....................................................................... 78

iii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Number Page

1. School District 1998 Demographics (OSPI 2007).......................................................... 5

2. School District 2007 Demographics (OSPI 2007).......................................................... 5

3. School District - Free and Reduced Lunch (OSPI 2007)................................................ 6

4. High School GPA by Ethnicity - 2006-2007.................................................................. 6

5. School District Lesson Design Policy.......................................................................... 19

6. School District Lesson Design Policy - Student Voice Pilot Project............................ 21

7. Teacher Participation: Percentage Participation versus Years of Experience.............. 30

8. Content Area Teacher Participation: Percentage Participation by Department............ 30

9. Student Participation: Percentage of Participants per Grade Level .............................. 31

10. Percentage of WOW Academy Student Participants by Ethnicity............................. 32

iv

LIST OF TABLES

Table Number Page

1. Timeline of Study......................................................................................................... 29

2. Youth Outcomes........................................................................................................... 64

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This dissertation would not have been possible without the support of the faculty of the

Leadership for Learning Program in the College of Education at the University of

Washington. Their guidance and instruction made the last three years a life changing

experience. A special thanks goes to my advisor, Dr. Mike Copland, for his advice and

insight into the world of doctoral research. I would also like to thank the staff and

students that played a significant role in making this study happen. Finally and most

importantly, to my wife Kim, and children Andrew, Rachel, and Melissa who allowed

their husband and father to spend the necessary time to get things done. Your sacrifices

are appreciated.

1

CHAPTER 1. ENGAGEMENT AND STUDENT VOICE

Introduction and the Problem of Practice

The 21st century learner requires a different approach from educators in order to

increase achievement in the classroom. It necessitates a higher emphasis on activities

that engage learners in the standards that have been developed by federal, state, and local

authorities as measurements of learning. To accomplish this task, a greater emphasis

needs to be placed on activities that allow for the emergence of student voice. This focus

provides an opportunity for adults to develop a greater understanding of the needs,

concerns, and struggles of todays students as well as the means by which they access and

process information. It also demands a close examination of how educators view their

role in relationship to classroom practices especially regarding the design of lessons and

units of study. For the system leader, the challenge is to create the conditions in which

student voice informs teacher practice leading to the design of engaging lessons for the

classroom.

In order for this challenge to proceed, it is important to examine the concept of

engagement, its relation to student achievement, and its connection to student voice.

Interestingly, research on the concept of engagement is relatively new thus a unified

definition of the term does not seem to exist. However, the literature suggests that there

are some common themes that provide insight into its meaning. First and foremost,

engagement reflects a persons active involvement in a task or activity (Appleton,

Christenson, & Furlong, 2008, p. 379). This involvement has been described as

infectious enthusiasm (Renzulli, 2008), which causes students to persevere in the face

of difficulty (Schlechty Center, 2008). Engagement is also associated with positive

academic outcomes, including achievement and persistence in school; and it is higher in

classrooms with supportive teachers and peers, challenging and authentic tasks,

opportunities for choice, and sufficient structure (Fredricks, Blumenfeld, & Paris, 2004,

p. 87). Ultimately, engaged students tend to earn higher grades, perform better on tests,

and drop out at lower rates, while lower levels of engagement place students at risk for

2

negative outcomes such as lack of attendance, disruptive classroom behavior, and leaving

school prior to graduation (Klem & Connell, 2004).

J ust as significant, the process of engagement is about building connections

between the students and the adults that work in the school setting. As such,

engagement is the opposite of alienation, isolation, separation, detachment, and

fragmentation. Persons are engaged to a greater or lesser degree with particular other

people, tasks, objects, or organizations (Newmann, 1989, p. 34). Therefore, in order for

high levels of engagement to exist, there must also be mechanisms in place that will

allow for open communication between adults and students. This is where the concept of

student voice enters the picture. At the most basic level, being heard becomes a

starting point where school personnel listen to students to learn about their experiences

in school (Mitra, 2006, p. 7). The hope is that this action will lead to a stronger student-

teacher relationship that creates higher levels of engagement.

Unfortunately for students, education has traditionally been an endeavor in which

they have limited control, participation, and voice in regards to their learning. Adults

create the standards as well as the lessons that will hopefully teach the corresponding

skills. Student input into these areas is rarely solicited even though they are the ones

being held responsible in the learning process. Thus a situation is created whereby

students are asked to meet requirements in areas in which they are not engaged.

Put most directly, it means that the group most affected by the direction of

educational policy, namely students and young people, currently have no

official voice. It is certainly not the case that they are hapless victims.

The evidence suggests the contrary. They are actively exercising their

right to resist, which means they are making choices to not learn. (Smyth,

2006, p. 282)

In this situation, heavy reliance is placed upon external motivators such as sanctions or

rewards in order to push students toward mastery. However, students who are

motivated to complete a task only to avoid consequences or to earn a certain grade rarely

3

exert more than the minimum effort necessary to meet their goal (Brewster & Fager,

2000).

The Local Context

As a context for this challenge, the Cascade Valley (pseudonym) School District

in Washington State has developed core beliefs around engaging students in the work

provided by teachers. Over the past 10 years, the district has partnered with an outside

agency, the Schlechty Center for Leadership in School Reform (SCLSR). This

organization, based in Kentucky and founded by Dr. Philip Schlechty, an educational

researcher and philosopher, works with districts across the country through the Standard

Bearer Network to create a framework on which to build a clear vision as they attempt a

transformation from a compliance and attendance based organization to one that

nurtures attention and commitment at all levels in the system (Schlechty Center, 2008).

In this vision, it puts the student in the center and asks teachers to design engaging work

that students will find meaningful and interesting. In looking at Cascade Valley over

time, it would appear as though the district has benefited from this partnership in that

there has been an obvious shift in staff development, budgetary focus, communication,

and collaboration towards engaging students in the work they are given in the classroom.

This has required a close examination of the various roles that people play inside a

learning organization and how they change with this new vision.

As far as the community of Cascade Valley is concerned, there is an interesting

mix between the past and present as the area is in the middle of a transformation process

from a more rural setting, to one that relies heavily on commerce. On one hand, there is

the presence of a small town feeling that is usually associated with areas that are a great

distance from urban centers. Many families that live in the area have done so for several

generations. They farmed the land and attended Cascade Valley schools; something their

children and grandchildren do today. However, as with everything, the community is in

the midst of change. What was once a farming based economy with single dwelling

homes has turned into a vision of capitalism. With the Port of Tacoma increasing in

traffic just to the north of Cascade Valley, so too have arisen mega industrial warehouses

4

on top of the fields that once produced cabbage, lettuce, and other vegetables. Right next

to these complexes are large-scale single and multi family developments that are

currently under construction. In a short time, these could double and even triple the

present population of the city. In addition, the middle of Cascade Valley has become a

commercial corridor bordering Interstate 5. A multitude of car and recreational vehicle

dealerships, large-scale furniture stores, and a sizeable casino now stand where smaller

mom and pop businesses once thrived.

Because of these changes, the district is experiencing some growing pains. In a

nine-year time-span, 1998 to 2007, there has been an obvious shift in the make-up of the

student population (see Figures 1 and 2). The current trend is that the number of white

students is on the decline and the number of students of color is on the increase, as well

as free and reduced lunch rates (see Figure 3). Additionally, grade point average

statistics reveal the existence of an achievement gap between different ethnicities in the

school (see Figure 4). The end effect is that conversations at all levels in the district now

surround the changing needs of the student population and how to provide them with the

best opportunity to achieve in the classroom. This is especially true as the district

attempts to meet the demands of the state assessments as well as the federal mandates of

No Child Left Behind. This is where the partnership with SCLSR has been valuable. It

helped to focus the conversations around what it means to be a true learning organization

and the roles that people play in such a system (see Appendix A). In this setting, the core

business of schools is to design engaging academic work for students and lead them to

success in that work (Schlechty Center, 2009). Clearly defining the focus of the

organization allows for a better emphasis on helping students to be engaged in their

education. Prior to this partnership, people often called any attempts at change random

acts of staff development due to the fact that educational trends would come and go with

no staying power. However, the vision of student engagement has been in place for

several years and is gaining power across the district.

5

Asian

5%

Indian

4%

Black

3%

Hispanic

8%

White

80%

Figure 1. School District 1998 Demographics (OSPI 2007)

Asian

10%

Indian

3%

Pac.Island.

3%

Black

4%

Hispanic

14%

White

66%

Figure 2. School District 2007 Demographics (OSPI 2007)

6

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

35%

40%

1998 2006

Figure 3. School District - Free and Reduced Lunch (OSPI 2007)

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

American

Indian

Asian Black Hispanic MultiRace Pacific

Islander

White

Figure 4. High School GPA by Ethnicity - 2006-2007

Activities Influencing This Project

One of the means utilized by the district to address some of the achievement

issues began in the winter of the 2006-2007 school year. At that time, district leaders put

a policy in place to increase student engagement through the emphasis on strategic lesson

design. The concept of Working on the Work (WOW) Academies was developed to

target teachers since lesson development is their responsibility. To get them to

participate, an incentive based model was used which provided them with two days of

time out of the classroom, access to a laptop computer, a protocol called Coaching for

Design (C4D) to provide a roadmap in the design, and a facilitator to guide them through

7

the process. The premise behind the C4D model is that traditionally, teachers have

employed a planning model when developing lessons and units of study. The problem is

that planning typically begins with an activity or content and asks the student to adapt

and fit that activity. Instead, C4D focuses on lesson design which begins with a hard to

teach or learn concept based upon student data (Washington Assessment of Student

Learning [WASL] scores, classroom based assessments, etc.). Using specific knowledge

about the students, lessons are built around their needs, motives, and values so that the

hard to teach or learn concept can be addressed in a more engaging manner. As an

additional piece to the policy, a communities of practice approach was implemented so

that the lesson design could be done in teams. This concept will be explored in greater

detail in chapter 2. Communities of practice refers to the idea that informal teams that

share common interests and passions can come together in order to solve problems. In

the case of this policy, the creation of these teams was left up to the teachers so that those

individuals interested in focusing on a particular area of student achievement could work

together toward a common goal. Since the implementation of this policy, Dr. Steve

McCammon (2008), declared that, our approach toward NCLB, which in most districts

is considered No Child Left Behind but in our district is widely referred to as No

Concept Left Behind.

Shortly after the implementation of the WOW Academies, the faculty and

administration at Cascade Valley High School began to have conversations surrounding

diversity and the changing demographics of the school. The purpose of these

conversations was to determine how the changes to the school would influence the nature

of teaching and learning in the classroom. During this time, it was determined that it

would be beneficial to gather student input on the issues of diversity within the school.

As a result, the staff selected five students of diverse backgrounds to participate in a

diversity summit sponsored by the local Educational Service District. Upon their return

from this event, the students began to talk with the administration about several negative

school situations related to diversity that they either experienced themselves, witnessed

first-hand, or had relayed to them by friends. They admitted that these events were never

reported to staff at the school.

8

It was at this time that the summit students and the Cascade Valley administration

decided the faculty needed to hear about these issues so that everyone had a better grasp

of what students of diverse backgrounds were experiencing on the campus. A fishbowl

activity was designed where the summit students served as a focus group during a general

faculty meeting. In this activity, the staff sat in a large circle surrounding the small group

of summit students. One faculty member served as a facilitator of the conversation with

the students. The entire faculty was to remain silent and listen as the facilitator asked

questions regarding experiences at the school that the students experienced. Each student

had an opportunity to share their thoughts to the large group.

Following the fishbowl activity, the students were excused allowing the faculty

time to reflect upon what they had heard. Overall the reaction by the faculty was one of

shock toward what the students had relayed. It was certainly contrary to their beliefs as

to how all students were treated at the school. As a result, the students were invited back

at a later faculty meeting to identify one area of focus related to diversity that could be

addressed by the school. Through a process of elimination, the combined group elected

to focus on the topic of words that hurt. With this hard to teach concept in mind, the

summit students and a select group of teachers participated in a WOW Academy so they

could use the C4D process to design a lesson for the entire student body. Over a two-day

span of time, the group created a lesson surrounding a video that they scripted and

produced using the video productions department at the school. The end result was a

virtual assembly where teachers lead students through a guided discussion on the effect

of word choice in a culturally diverse setting.

Concurrent with the fishbowl activity that was underway, administrators in the

district were having conversations with a large computer software company regarding the

work that was happening in the district. In the midst of that conversation, it was revealed

that prior to this company producing and distributing a product to customers, that they

conduct a series of focus groups. The purpose of these groups is to solicit customer

needs and desires when it comes to the product. The philosophy behind this way of

doing business was very clear get to know your customer. Interestingly enough, this

philosophy was very similar to the work being done in the Cascade Valley School

9

District. As mentioned above, the C4D protocol helps teachers to design lessons but only

after they have a chance to really know their customers, the students.

The experience of listening to students voicing their concerns over issues in the

school in a controlled setting resulted in an end product that was tailor made to the

students at Cascade Valley High School and appropriate to their needs as a group. With

that in mind as well as the conversations that occurred with the software company.

Cascade Valley administrators began to see the potential of using student voice to

influence outcomes directly related to teaching and learning. Starting with the 2008-2009

school year, Cascade Valley system leaders began the push toward making student voice

a major focus in the conversations surrounding engagement. As a result, a new

component was added to the lesson design policy. As part of the student data collection

process used prior to the lesson design, teams from Cascade Valley High School began to

pilot student focus groups as a means of gathering additional information. The emphasis

is on questioning students about how they process information related to the content. The

goal is to use this information in tailoring lessons that will make the hard to teach

concepts more manageable. It is also meant to strengthen the teacher-student relationship

through the creation of a process whereby teachers listen to student experiences, and

students have the opportunity to speak. In the end it is the hope is that both of these goals

will lead to greater student engagement in the classroom.

Literature Influencing This Project

Three major issues have emerged that contribute to the need for educators to look

at student voice within the context of engagement. The first of which is the mandates

surrounding No Child Left Behind and its focus on standards and assessment. This

policy has saturated public school classrooms with strict educational edicts which all

students and teachers are required to meet or exceed. A visit to the Education World

(2008) Web site reveals that the political and educational communities have created

pages and pages of standards to cover almost every conceivable function in our schools.

In all there exist 12 detailed sets of national standards around the various school

disciplines (i.e., fine arts, language arts, and mathematics). Combined with the

10

exhaustive record of individual state standards (which often overlap or conflict with the

national standards) and local standards that emphasize graduation and behavior, it all

becomes hard to comprehend and problematic to manage.

Nevertheless, in this era of accountability, it has become the job of educators to

uphold these standards and deliver them to students. Then students are given a barrage of

assessments to ensure that the educators are doing their jobs correctly and that the

students are learning what is deemed essential by the agencies responsible for developing

the standards. Kohn (2000) summarized this situation in the following manner:

The top-down, heavy-handed "Tougher Standards" movement has taken

over many schools, with full support of business groups, politicians, and

many journalists. Primary opponents are classroom teachers and parents.

Raising standards translates into higher scores on poorly designed tests.

Unfortunately, what is often missing from this movement is that standards are not alone

in addressing the needs of students in the educational setting. In order to facilitate

learning, students must have more than just a decree or raised bar that they must jump

over. Students must be personally connected with the material so that they have a reason

to want to meet the standards placed in their path.

To make such a decision to comply with the institution of schooling, the

young person has to have some personal connection to the school, a stake

in what the school is perceived to offer, and a sense of the worthwhileness

of the schooling experience. The young person has to decide to comply

with the school experience and school staff, rather than reject and resist

them. The starting point for facilitating such decision making by young

people is likely to be when the school, its teachers, and leaders reach out

to such children, move to meet them rather than expecting them to adjust

to the entrenched school and teacher paradigms, and attempt to engage

them in relevant and interesting school experiences in which they can

recognize themselves, their parents, and their neighbours. (Angus, 2006,

p. 370)

11

In other words, the act of establishing a standard does not address whether it is relevant to

the student or whether they are engaged in the process of learning said standard.

The second issue to emerge which creates the need to focus on student voice and

engagement is the technological revolution that has exploded across the globe. Today the

proliferation of personal cell phones and electronic music devices permeates the culture.

The same could be said for a trip to the homes of our students. Personal computers have

become one of the centerpieces of the family dynamic. With the Internet, e-mail, texting,

instant messaging, Myspace, and Facebook to name a few, students have the ability to

amass huge quantities of personal contacts or friends, as well as access to infinite

amounts of information.

A really big discontinuity has taken place. One might even call it a

singularity an event which changes things so fundamentally that there

is absolutely no going back. This so-called singularity is the arrival and

rapid dissemination of digital technology in the last decades of the 20th

century. (Prensky, 2001, p. 1)

It is evident that these digital natives are being affected by the changing world around

them.

Digital Natives are used to receiving information really fast. They like to

parallel process and multi-task. They prefer their graphics before their text

rather than the opposite. They prefer random access (like hypertext). They

function best when networked. They thrive on instant gratification and

frequent rewards. (Prensky, p. 2)

This access to technology has caused teachers to struggle more with the traditional role as

deliverers of information. Since many students have this information at their fingertips,

they become less patient with sitting in rows performing one task at a time. And as

students continue to increase their network of friends, they are less likely to turn to

adults for the answers and direction. The bottom line is that this generation of learners

12

processes information differently from the generation beforethe ones that are creating

the standards and delivering the lessons in the classroom. It is here that student voice

becomes a crucial step in understanding and acting upon this difference.

Like those in charge of the health care and legal systems, educators think

that we know what education is and should be. Because we have lived

longer and have a fuller history to look back upon, we certainly know

more about the world as it has been thus far. But we do not know more

than students living at the dawn of the 21st century about what it means to

be a student in the modern world and what it might mean to be an adult in

the future. To learn those things, we need to embrace more fully the work

of authorizing students' perspectives in conversations about schooling and

reform--to move toward trust, dialogue, and change in education. Because

of who they are, what they know, and how they are positioned, students

must be recognized as having knowledge essential to the development of

sound educational policies and practices. (Cook-Sather, 2002, p. 12)

To address both issues mentioned above, educators must redefine the role of the student

and the overall scheme of the learning process. As far as the student is concerned, their

place in the system is much like that of an indentured volunteer. Schlechty (2001)

suggested that while their attendance is mandatory, the effort and attention they give to

the tasks at hand is dependent upon the level of engagement students have with the

material and what it means in their life. He also described the contemporary student as a

customer of quality schoolwork much like a consumer who shops a store based upon

the value of the product that is offered. These concepts of student as volunteer and

customer are somewhat radical in the education world where the traditional view of the

student is one of empty vessel to be filled or even inmate in the prison.

A change in the students role, necessitates a change in the teachers role.

Schlechty (Schlechty Center, 2008) described this as a shift towards a leader and

designer of engaging work for kids rather than the traditional role of performer,

presenter, or diagnostician. He continued to point out that the work they provide to

13

students is one of the only things that they have complete control over when it comes to

their job. They do not control which students are assigned to their classroom, the

previous knowledge these students bring with them, the standards that are created by

legislators, or the bell schedule of the school. Brewer and Fager (2000) pointed out that

teachers can influence student motivation; that certain practices do work to increase time

spent on task; and that there are ways to make assigned work more engaging and more

effective for students at all levels. With that in mind, it would make sense that a

teachers best use of time and energy is in improving the quality of the work given to

students. As far as this is concerned, Wasserstein (1995) drew five conclusions for

teachers to consider when creating work for students: (a) students of different abilities

and backgrounds crave doing important work, (b) passive learning is not engaging, (c)

hard work does not turn students away, but busywork destroys them; (d) every student

deserves the opportunity to be reflective and self-monitoring, and (e) self-esteem is

enhanced when [students] accomplish something [they] thought impossible. One

potential method for creating this environment comes from Hidi (1990) who discussed

the concept of situational interest. This is where a teacher generates conditions and/or

stimuli in the classroom that focus attention to a particular topic or concept. She argued

that this can play an important role in learning, especially when students do not have

pre-existing individual interests in academic activities, content areas, or topics which

described most of our students relative to our core academic disciplines. Additionally,

she suggested that the utilization of this method could make a significant contribution to

the motivation of academically unmotivated children.

The third issue related to engagement and student voice comes in the increased

levels of student dissatisfaction that are emerging across the country. Newmann (1992)

suggested that,

Engagement involves psychological investment in learning,

comprehending, or mastering knowledge, skills, and crafts, not simply a

commitment to complete assigned tasks or to acquire symbols of high

performance such as grades or social approval. Students may complete

academic work and perform well without being engaged in the mastery of

14

a topic, skill, or craft. If fact, a significant body of research indicates that

students invest much of their energy in performing rituals, procedures, and

routines without developing substantive understanding. (p. 12)

In fact, data from 2003 indicated that 3.5 million youth and young adults ages 1625

years old had not earned a high school diploma and were not currently enrolled in school.

Additionally, since peaking at 77.1% in 1969, high school completion rates had declined

to estimates as low as 66.1% by 2000 (Barton, 2004). Combined with 2006 data that

suggests that 50% of our students are bored every day in high school (Yazzie-Mintz,

2006), it is apparent that there is an alarming trend happening in American education.

Interestingly enough though, of those student who indicated they were bored, close to

75% of the students cared about their school (Yazzie-Mintz). This suggests that there are

different types of engagement that occur in the school that are influenced by the social

context and the ways in which individuals process their environment (Furrer, Skinner,

Marchand, & Kindermann, 2006). These differences include cognitive, behavioral, and

emotional engagement; each of which lead to the academic, social, and emotional success

or lack thereof for students.

One possible means to address these different levels of engagement is the use of

student voice. Three studies in this emanating from the United States, Canada, and

England involved educators bringing students into the school reform process to seek their

opinions as to how best to carry out change. The Manitoba School Improvement

Program (MSIP) in Manitoba, Canada and the Bay Area School Reform Collaborative

(BASRC) in California both found that students improved academically when teachers

construct their classrooms in ways that value student voice-especially when students are

given the power to work with their teachers to improve curriculum and instruction

(Mitra, 2004, p. 653). More specifically, the MSIP found a correlation between an

increase in student voice in the school culture and an increase in school attachment

(Mitra, p. 653). These studies also uncovered that the effects of the student voice

activities extended beyond the classroom.

15

In some schools parents can be an active barrier to change as they fear

what they consider to be experimentation on their children. But when

their children talk to them about their experience of schooling, and parents

really hear, there can be far more openness to considering alternative

practices. (Levin, 2000, p. 160)

In regards to the BASRC, students were given the opportunity to serve on Student

Forums that would provide educators with useful information about the classroom.

Student Forum members served as "experts" of the classroom experience

in a variety of activities. They provided teachers feedback on how students

might receive new pedagogical strategies and materials through

participation in teacher professional development sessions, such as a

training on developing standards-based curricular units. Throughout the

training sessions, they shared with teachers how they would receive the

new lessons being developed and suggested some ideas for how to make

the lessons more applicable to students' needs and interests. (Mitra, 2003,

p. 293)

In the third study, beginning teachers in England were trained on a new approach

for the classroom called student consultation. Rudduck (2007) described this as:

. . . seeking advice from students about possible new initiatives; inviting

comment on ways of solving problems, particularly about behaviours that

affect the teachers right to teach and the students right to learn; and

inviting evaluative comment on school policy or classroom practice.

Consultation is a way of hearing what young people think within a

framework of collaborative commitment to school reform. (p. 590)

The benefit of this system is that student consultation helps teachers develop a

practical agenda for themselves, while at the same time providing for stronger self-

esteem for students.

16

Overall, the literature points to the following conclusions around the use of

student voice in the educational setting:

Engaged students are central to lasting school improvement. The reality is that

most schools are not organized in a manner that will allow for students to be active

participants in the discussions on school improvement. In both the MSIP and BASRC

examples mentioned above, structures were changed over periods of time at both the

school and classroom levels to bring students into the conversation about learning. What

was discovered was that this change helped to re-engage alienated students by providing

them with a stronger sense of ownership in their schools (Mitra, 2003, p. 290). It also

provided students with a sense of belonging which implies an active engagement with

the organization (Levin, 2000, p. 164). Overall, increasing student voice has been

found to improve student learning, especially when student voice is linked to changing

curriculum and instruction (Oldfather, 1995, p. 136).

Teachers attitudes can be changed through student voice. In order to move

students to a level of engagement that will provide them with ownership and belonging in

the school setting, teachers must be convinced that student voice has benefits not only for

students, but for themselves as well. As with Cascade Valleys fishbowl activity, the

studies mentioned above found that having students involved in the conversations on

learning did change the way teachers reacted to forms of information.

. . . data from students had a powerful influence on the willingness of

teachers to consider real change. Many teachers were quite able to reject

external research as a basis for change, and even to reject the experience

of other schools. But when surveys of students in their own school showed

significant levels of boredom or disaffection, teachers found this evidence

compelling. (Levin, 2000, p. 159)

In addition, the physical presence of students at gatherings influenced the way many

teachers behaved with each other and how they interacted.

J ust having students present in the room changed the tenor of meetings.

Resistant teachers particularly were less likely to engage in unprofessional

17

behaviors such as completing crossword puzzles during staff meetings or

openly showing hostility toward colleagues. (Mitra, 2007, p. 734)

The end result is that many teachers reported the need for a more cooperative relationship

between adults and students. They discovered that,

Teachers cannot create new roles and realities without the support and

encouragement of their students: students cannot construct more

imaginative and fulfilling realities of learning without a reciprocal

engagement with their teachers. We need each other to be and become

ourselves, to be and become both learners and teachers of each other

together. (Fielding, 2001, p. 108)

End Product

The overall goal of this project is to guide the future use of student voice activities

as a means of increasing engagement in the Cascade Valley School District. It is hoped

that by the end of the study, conclusions can be drawn around this process and the

methods used to incorporate student voice into the educational setting. These

conclusions will inform the future adaptations of WOW Academies and the structure of

the C4D protocol. Since this is the primary means of increasing student achievement in

the district, the entire school system will benefit from any potential changes. More

specifically, it will lead to the construction of a Student Voice Initiative Web site

intended for use by staff, students, and parents in the greater Cascade Valley community.

This Web site will serve as a guide for teachers to create proposals around hard to teach

concepts that they wish to bring to the WOW Academy setting. The Web site will also

house research around student voice, engagement, and communities of practice so that it

can help guide teacher practice.

18

CHAPTER 2. INQUIRY DESIGN

The C4D Proposal

As mentioned earlier, the C4D protocol emphasizes the use of lesson design

around student needs and interests. This is in contrast to the traditional lesson

development process used by teachers which emphasizes planning and creating activities

based around the subject matter. The tool was adopted in the Cascade Valley School

District during the winter of the 2006-2007 school year. From that time until the fall of

2008, several teams of teachers were able to experience the protocol consisting of several

steps intended to assist with the design process. These steps included (see Figure 5):

1. School/classroom data. This step involves the location and collection of

various forms of data that exist in the school. This could include WASL

scores, other achievement test scores such as SAT/ACT, and Classroom Based

Assessments.

2. Identification of hard to teach and/or learn concepts. This step involves

mining the data from the previous step for obvious indicators of student

difficulty. These indicators point to concepts that teachers have problems

teaching or that students have problems learning.

3. Specific student data. Teachers are asked in this step to identify students

inside their own classrooms that are struggling with the concepts. They are

asked to describe the characteristics of these students including their previous

grades, their interests, and needs.

4. Coaching: A facilitator intervenes during this step to make sure that the

teaching team has a good grasp of the information surrounding their students.

5. Lesson design. Armed with the knowledge from the previous steps, teachers

can then go and design lessons that are specific to their students.

6. Lesson delivery. This step is back in the classroom where the teacher, or

teachers, present the lessons designed.

19

7. Lesson assessment. This step involves the assessment of the students that

takes place after the lesson presentation to see if there is improvement in the

students understanding of the concept(s).

8. Lesson evaluation. This step involves the teacher evaluating whether the

lesson met the intended outcome. This information can be used as data back

in the beginning steps thus creating a cyclical process for lesson design.

School/Classroom

Data

(WASL,ClassroomBased

Assessments,SAT/ACT)

IdentificationofHard

toTeachand/orLearn

Concepts

SpecificStudentData

(Previousgrades,readinglevel,interestareas.)

Coaching

(Workingwitha

facilitatortoblend

specificstudentdata

withhardtoteach

and/orlearnconcepts)

LessonDesign

LessonDelivery

Student

Assessment

Figure 5. School District Lesson Design Policy

The Student Voice Pilot Project

Starting in the fall of 2008, the staff at Cascade Valley High School began a pilot

project which created additional steps in order to utilize student voice as a part of the

protocol. These steps included (see Figure 6):

20

1. Target Group. This step requires staff to identify a specific student target

group experiencing difficulty with the hard to teach or learn concept. In many

cases this group is determined by test scores or other classroom based

experiences.

2. Target Questions. This step involves the creation of questions to be directed

toward studentsspecifically the members of the target group mentioned

above. The intention of these questions is to find out why students find

concepts difficult or to determine how they think and learn.

3. WOW Team. This step involves the identification of staff members who are

interested in improving student achievement in the hard to teach and learn

concept area.

Following these steps, a critical piece to the student voice process was addedstudent

focus groups. In theory, the use of focus groups would allow the WOW Team to meet

with members of the student target group with the intent of learning more about the

intricacies of the modern day K-12 student. The WOW Team members were charged

with conducting the focus groups and asking the questions that were developed in the

previous step. It was also their role to evaluate the student responses in order to assist

with the next steps in the lesson design process. The goal of these additional steps was to

solicit student voice as one aspect of increasing the knowledge that teachers have

regarding their students. The hope was that this information would be included in the

lesson design process so that the final lesson outcome better engages students in the

classroom.

21

School/Classroom

Data

(WASL,ClassroomBased

Assessments,SAT/ACT)

IdentificationofHard

toTeachand/orLearn

Concepts

SpecificStudentData

(Previousgrades,readinglevel,interestareas.)

Coaching

(Workingwitha

facilitatortoblend

specificstudentdata

withhardtoteach

and/orlearnconcepts)

LessonDesign

LessonDelivery

Student

Assessment

SpecificTargetGroup

StudentFocusGroups

TargetQuestions WOWTeam

Figure 6. School District Lesson Design Policy - Student Voice Pilot Project

Framing the Problem of Practice

Overall, this study attempts to address a question of system level leadership which

states: How can a learning organization create the capacity for student voice to

influence teacher practice around lesson design so that the end result is an increase in

student engagement and overall achievement? In order to answer this question, two sub

questions must be discussed in relation to student voice:

Subquestion 1. If one of the goals of this study is to influence teacher practice,

how does this process contribute to their professional and social needs resulting in a

22

greater investment in their roles as designers of engaging work for students? In other

words, how does this process increase the engagement levels of teachers so that it

influences them to change their practice around lesson design? For the most part, in

order for teachers to feel successful in their jobs, they need to have a certain level of

professional and social satisfaction. On the professional side, this may appear in the form

of administrative support, collegial dialogue, and systems and tools that will aide them in

completing their job. Socially, teachers need to be surrounded by colleagues that share

their interests and concerns. They also need to have positive interactions with the

students that are in their care on a daily basis. Unfortunately, in many schools, these

situations do not always exist. Over the years, teachers have acted in isolation inside the

classroom delivering content along with diagnosing and taking corrective actions when

necessary around certain lessons. The act of collaborating with other teachers on a

concept while soliciting student input can be quite foreign. In other situations, they are

forced to work in teams with people that do not share common interests or desires

concerning the future of students. Either way, this can leave teachers in a professional

and social void.

In the Cascade Valley School District, WOW Academies operate on the basis of

the communities of practice theory. For that reason this study will use this theory as a

lens in order to draw conclusions on the questions above.

Communities of practice are groups of people informally bound by shared

expertise and passion for joint enterprise. In organizations that value

knowledge, they can help drive strategy, solve problems quickly, transfer

best practices, develop professional skills, and help recruit and retain

talented employees. (Wenger & Snyder, 2000, p. 139)

Communities of practice differ from other organizational forms such as formal work

groups, project teams, and networks because they are informal and have the ability to set

their own agenda as well as leadership structure. In Cascade Valley, informal teams with

a common goal of improving student achievement around a concept could apply to

23

become part of a WOW Academy. This left the team formation, the direction of the

team, and the leadership inside the team entirely up to the members.

Three key components make up the foundation of the Communities of Practice

theory. Each plays a role in the WOW Academies and the pilot project involving the

student focus groups.

1. Participation. This involves the make-up of the team that comes together and

the work they do as a team in arriving at a shared meaning and understanding.

It can refer to an individuals involvement in the development of questions,

interactions with students in the focus group, observational records/data

collection, and personal conclusions drawn from the data.

2. Negotiation of Meaning. Negotiation of meaning refers to the means by

which change turns into practice. It relates to the intersection of the

interactions among the people in learning communities (participation) and the

resulting understandings (reifications) (Coburn & Stein, 2006). Negotiation

of meaning is what happens during the participation process which leads to

greater common knowledge and similar practice. In the case of the pilot

project, it can involve the mining of the data collected, conversations about

the focus group process, and conversations about the data that lead to team

meaning.

3. Reification. Reification is the substance that is created as part of the meaning-

making. It is not only the hands-on tangible materials; it is also common

ideas and concepts that emerge as a result of the negotiation process.

Reifications emerge from social processes and provide a concrete

representation of the processes that produced them by capturing and

embodying experience in fixed form (Coburn & Stein, p. 29). In the case of

the pilot project, it involves the things that are produced that demonstrate

evidence of a change in teacher practice around lesson design and engaging

work for students.

24

Overall, if the use of Communities of Practice provides teachers with the necessary

professional and social support, then they will have a greater investment in the process.

This in turn will result in a more serious look at the hard to teach/learn concepts and a

greater desire to design work for students. In other words, the potential is there to

increase the engagement of teachers in their work. If teachers are not engaged in the

process, then the hopes of them producing work that is engaging for students is quite

slim.

Subquestion 2. If the overall goal of this study is to increase student

achievement, how does this process contribute to satisfying their academic and social

needs, resulting in a greater investment in their educational setting? J ust like teachers,

students also have needs in the education setting. For the most part, their needs can be

summed up in the academic and social realms. Academically, students need to be

challenged with relevant curriculum that is age and time appropriate. As volunteers in

the system, they pick and choose from the menu that is put in front of them by teachers

and make decisions as to what they are able and willing to accomplish. Socially

speaking, they need to interact with their peers while at the same time build strong

relationships with the adults that are in charge of their education.

Unfortunately for many students, one or both of these needs are not met in the

educational setting. What is most troubling is that those students who struggle

academically or socially-emotionally all to often are students of color, second language

learners, or students of poverty; the voices of these students are often muted or even

silenced in most schools (Campbell, 2009, p. 19). As a result, we have an inequitable

situation that creates higher drop-out rates for minority students as well as the

achievement gap that exists in our public schools across the nation. Rather than devote

time to the students and their individual or group needs, fault for the failure is often

attached to the students that are struggling. The term for this action is called

pathologizing which refers to:

. . . a process of treating differences as deficits, a process that locates the

responsibility for school success in the lived experiences of children

(home life, home culture, SES) rather than situating responsibility in the

25

education system itself. In large part because educators implicitly assign

blame for school failure to children and to their families, many students

come to believe they are incapable of high-level academic performance.

(Shields, 2004, p. 112)

Whether this occurs in open public view through policies or procedures that are

discriminatory in nature or through hidden means with beliefs and practices of the people

in the system, the results are the same in that equity is not achieved. Going back to the

question at hand, if we seek higher levels of achievement through engagement and

investment on the part of students, then equity must be a goal and a lens by which this

study draws conclusions. In other words, does the process of C4D and student voice

attempt create an equitable situation for students?

So then what is equity and how does it apply to a school system? Before

providing a definition, Kahle (2004) argued that equity has three dimensions. The first

refers to the resources that are available to communities and the families that reside in

that community. The second dimension looks at the systems educational plan and

practices. This refers to the quality of the curriculum and the preparation of the adults in

that system to deliver this curriculum. It also has to do with how students are treated in

the various subgroups and whether teachers and administrators hold different goals for

specific subgroups as opposed to others in the system. The final dimension of equity is

the outcomes for students and whether different outcomes exist for the various

subgroups. Using these three dimensions, we can define an equitable system as one in

which identifiable subgroups of people do not experience systemic discrimination in

process, in opportunities, or in negative outcomes without an ethically sufficient reason

(p. 12). To go even deeper, the system is:

one in which all children have the opportunity to achieve to their fullest

potential or to the levels specified in the systems performance standards;

one that is committed through its allocation of resources to the equitable

achievement of all culture and gender based student populations;

26

one in which participation of diverse groups, particularly those groups

traditionally under-represented in the system, is expected and facilitated;

one that is accessible; for example, sensitivity to individual variation is

considered; and

one that has policies and procedures established and followed for distributing

and utilizing resources in ways that narrow any identified differences between

subgroups. (pp. 12-13)

My Location within the Project

In addition to being the primary researcher in this project, I have also served a

role within the Cascade Valley School District in carrying out the direction set forth by

the system leaders. As Principal of Cascade Valley High School, it has been my job over

the last two years to help assist teams from my building in their preparations to attend the

WOW Academies. This means that I have been facilitating conversations so that teachers

will be organized to get maximum benefit from the process. These conversations include

the concept(s) that they choose to bring to the C4D process, identifying the target group

of students they feel would benefit from this work, selecting students from the target

population to make-up the focus group, and designing the questions they ask students

inside the focus group. I have also been an observer during the WOW Academies as the

teacher teams work to design lessons.

During the course of the study, my duties did not change in relation to the district

philosophy of WOW Academies and the focus on hard to teach and learn concepts. The

only difference was my observations of the process in regards to how teams used the

student voice information as they proceeded with the protocol. I also directed the data

gathering following the WOW Academies for use in determining the next course action

for my own school as well as the district.

As far as others involved in this study from inside the district, the Superintendent

and WOW Coordinator have been instrumental in setting the vision for the district in

regards to the use of student voice, developing the process by which the C4D protocol

could be utilized, selecting the teams to participate in the WOW Academies, and

27

allocating resources for the WOW teams to meet outside the classroom. Additionally, I

have relied on teacher collaborators to volunteer to work on hard to teach concepts and

developing questions for the student focus groups. Finally, students were also

collaborators through their willingness to participate in the focus groups.

28

CHAPTER 3. METHODS

Type of Study

This study was qualitative in nature since the primary means by which data was

collected was through observations and interviews. Also, due to my position in the

district and the fact that the goal of the study is to inform system leaders about the future

use of student voice in this setting, action research was chosen methodology. In addition

to being an appropriate means of learning from activities and contributing to the

collective knowledge in the district, action research is based on principles of

collaboration, democratic participation, and social justice and empowerment. These are

the same principles that undergird meaningful student voice efforts. (Campbell, 2009, p.

19). Thus, this method is a solid fit for this particular study.

Boundaries

As mentioned in chapter 1, the work involving the C4D protocol began during the

2006-2007 school year. However, the timeframe for this particular study begins later in

time and encompasses the WOW Academies and interviews of participants including

high school staff and students. The first Academy began in October of 2008 and the final

one occurred in March of 2009 (see Table 1). All together, this study encompassed work

done a total of 8 different teams, each attempting to tackle a hard to teach and/or learn

concept. These concepts include:

1. English art of commentary/analysis in student writing.

2. Math/English deciphering math word problems.

3. World Languages fluency issues.

4. Social Studies research techniques and citations.

5. Career and Technical Education critical thinking skills.

6. Video Productions writing process in relation to script creation.

7. Social Studies economic systems.

8. Social Studies primary and secondary sources.

29

Work that led up to these academies included staff development during the high school

summer staff retreat, creation of teams within school, prioritization of concepts to bring

to the academies, potential questions to ask students at the beginning of the C4D process,

and the selection of teams to attend academies.

Table 1. Timeline of Study

Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr

Activities 2008 2009

Pre-WOW Academy Meetings

WOW Academy I

WOW Academy II

WOW Academy III

WOW Academy IV/V

WOW Academy VI/VII

WOW Academy VIII

Teacher Interviews

Administrator Interviews

Student Interviews

Participants

The participants in the WOW Academies included both staff and students from

the high school. The total number of staff included 30 individuals. They comprised a

wide range of experience and represented several different content areas in the school

(see Figures 7, 8, and 9). Since the philosophy in the district is based upon a

Communities of Practice theory when it comes to the WOW Academies, staff members

created their own teams and decided upon the concepts that needed attention. They then

30

wrote proposals to be reviewed by the district WOW Coordinator and the Superintendent

in hopes that they would be selected to participate.

Figure 7. Teacher Participation: Percentage Participation versus Years of

Experience

Figure 8. Content Area Teacher Participation: Percentage Participation by

Department

31

Figure 9. Student Participation: Percentage of Participants per Grade Level

As far as student participation in the WOW Academies is concerned, 38 students

took part in the focus groups as a part of this process. The represented all age groups in

the school grades 10 through 12 (see Figure 10). Out of the 38 students, 52% were male

and 48% females. Additionally, the students also reflected the same ethnic demographic

date as shown in Figure 2 in chapter 1 (see Table 2). While teachers in this activity self-

selected, students came to the process in a different manner. Once the teacher teams

were formed and the target group of students had been identified, then came the task of

narrowing down that group to a manageable number for the student focus groups. The

goal was to have between 5-7 students per focus group. As a result, during the course of

the study students were selected to the focus groups in one of two ways. The first way

and the one that was used most frequently in 7 of the 8 WOW Academies involved a

random selection. For each WOW Academy using this method, all members of the target

group were imported into an Excel spreadsheet and assigned a number. Then, using a

random integer generator (http://www.graphpad.com), numbers were randomly selected.

The students who were assigned those numbers were then brought into a room together,

given an introduction to focus groups, and given the opportunity to accept or decline the

invitation. Out of this process, 37 students were randomly drawn, 30 accepted the

opportunity to participate in the focus groups, and 7 withdrew. The second means by

which students were selected to participate in focus groups involved a more deliberate

selection of students. This occurred in 1 of the 8 WOW Academies during the course of

32

the study. Once again a target group was identified for the hard to teach and learn

concept. Then, the team of teachers participating in the WOW Academy hand selected

students that they knew from their class rosters fit within this target group. The idea

behind this was to look at students that did not provide significant feedback during the

school day. The WOW Team wanted to hear from this group so they could design

around them specifically. Using this process, 8 students were contacted to be a part of

this WOW Academy and all 8 participated.

Figure 10. Percentage of WOW Academy Student Participants by Ethnicity

Data Collection

Data collection for this study came in the form of personal observations and

interviews of the participants. As far as observations were concerned, these took place in

three different phases of the process:

Phase 1: Pre-Focus Group Meetings. These meetings took place prior to the

WOW Teams entering the WOW Academies. The make-up of the group

varied between all participants or one to two lead members. The

conversations in these meeting included the selection of the target group, the

33

methods by which students would be selected from the target group focus

group participation, question development, and the focus group protocol

(questioning strategies, note taking . . . ). These conversations ranged

between one half hour to one hour in length.

Phase 2: Focus Group Sessions. These sessions occurred during the actual

WOW Academies. All WOW Team members were in attendance as well as

the student participants. Observations in this setting focused on the flow of

the sessions, the teachers role in the focus groups, and the students level of

participation throughout the process.

Post-Focus Group Sessions. Following the focus group session, students were

dismissed leaving the WOW Team to wrestle with the information given to

them by the students. Observations here included their conversations

surrounding that process.

The second means of data collection came in the form of interviews following the WOW

Academies. These interviews were done in a focus group setting much like the work

done in the pilot project. Participants for these focus groups consisted of the WOW

Team members and the student focus groups. Their involvement was on a voluntary

basis. In all, a total of 14 teachers participated in 3 focus groups, and 13 students

participated in 3 focus groups. In addition, one administrative focus group was added

with individuals who assisted with the WOW Academies throughout the course of the

study. This group consisted of 2 participants.

Conducting all of these data collection focus groups was an outside facilitator.

Questions were prepared ahead of time and distributed to the participants prior to their

arrival to the focus group sessions (see Appendices B-D). These questions were crafted

toward drawing out their experiences during the WOW Academies. Time was also

allotted during the focus groups for individuals to write out some of their responses to the

questions. These responses were collected at the end of each session for review with the

other sources of data. Also, each focus group was recorded for review at a later date in

order to capture responses and important trends in the data.

34

For purposes of anonymity in the study, all participants in the data collection

process were provided with a special code so their responses would not be attributed back

to them when the results of the research became published. All observational notes as

well as information written through the interview process made use of these codes. The

codes themselves along with their corresponding names have been kept in a secure

location. Also, all student participants in the interview process were required to have

parental permission prior to the start of the data collection (see Appendices E and F).

35

CHAPTER 4. MAKING SENSE OF THE DATA

Personal Observations and the Focus Groups

For the most part, all of the comments and the behaviors exhibited by staff and

students during this study were positive toward the use of student voice as a part of the

lesson design process. That is not to say that everything went smoothly as far as the

planning and questioning phases were concerned. In fact, it was quite apparent that there

was a great deal of apprehension and nervousness on the part of staff in the beginning

stages. During the pre-meetings to develop questions, several people had difficulty

grasping the concept of how students would enter into the C4D protocol and how they

would be able to use the information they gathered from the kids. At the same time,

students also exhibited a level of uneasiness in the beginning stages at the prospects of

joining their teachers for a conversation about the classroom. However, once the WOW

Academy focus groups got underway, this anxiety on the part of both groups evaporated

and the conversation and transfer of information was able to occur. As a result of this

work, staff and students were able to discuss and write about their experiences at the end

of the study in the interview focus group settings. After a careful review of this data, it