Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Chapter 08

Hochgeladen von

airies920 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

15 Ansichten13 SeitenThis document provides an overview of how syntacticians analyze sentences using phrase-structure trees. It begins by introducing phrase-structure trees and how they are used to break down sentences into constituent phrases. An example sentence is broken down into its noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases, and clauses. The document then discusses how these phrases and clauses are labeled and how phrase-structure trees are built according to general patterns in a language called phrase-structure rules.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis document provides an overview of how syntacticians analyze sentences using phrase-structure trees. It begins by introducing phrase-structure trees and how they are used to break down sentences into constituent phrases. An example sentence is broken down into its noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases, and clauses. The document then discusses how these phrases and clauses are labeled and how phrase-structure trees are built according to general patterns in a language called phrase-structure rules.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

15 Ansichten13 SeitenChapter 08

Hochgeladen von

airies92This document provides an overview of how syntacticians analyze sentences using phrase-structure trees. It begins by introducing phrase-structure trees and how they are used to break down sentences into constituent phrases. An example sentence is broken down into its noun phrases, verb phrases, prepositional phrases, and clauses. The document then discusses how these phrases and clauses are labeled and how phrase-structure trees are built according to general patterns in a language called phrase-structure rules.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 13

Chapter 8

Syntactic Structure & Typology

In the previous chapter i talked about the sort of things that syntactic research is about, the kind

of questions about language use and linguistic behaviour that syntacticians are interested in, and

the kind of data that they consider relevant to their work. Now it's time to show you a little bit

of how syntacticians analyze the sentences of human language.

1

Phrase-Structure Trees

You may or may not be aware of it, but when we hear a sentence (assuming it's in a language we

understand) we not only recognize the individual words but have a habit of grouping them into

larger constituents, into phrases. And the same thing happens when we compose a sentence to

say or write. I'm going to try to demonstrate this process using the following sentence:

The girl with the blue barrette is speaking to that quiet boy.

OK, the way i've got it here, it's just a sequence of twelve words; there's no obvious internal or-

ganization, at least not visually; not even any punctuation. But any fluent speaker of English

will immediately conclude that the words the and girl go together; likewise the words that,

quiet, and boy; likewise the words the, blue, and barrette. There are two ways this kind

of association is usually represented, and i'm going to show you both. We can put square brack-

ets around each of these groups of words, or we can draw lines to connect them like this:

[The girl] with [the blue barrette] is speaking to [that quiet boy]

Alright, now let's look at this word to; what do you think it goes with? Fine, let's call that a

larger constituent and mark it accordingly. And we can do the same with the word with and

the phrase the blue barrette, right? And what about these two phrases, the girl and with the

blue barrette? Should they go together? Right, OK, let's put them together like this:

[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is speaking [to [that quiet boy]]

1

The presentation i'm about to give you is based on what is often called the Standard Theory of syntax, which was

developed back in the 1960's, mostly by the famous linguist Noam Chomsky at MIT and his students. Much of this

theoretical background is assumed to some extent or another by almost all syntacticians today, even when all they

do with it is explain why they disagree with it, and this is the reason why in my senior class on syntactic theory i

spent the first half of the first semester explaining it in detail to my students. I'm telling you this so you'll know that

most the details in this presentation you cannot assume to be correct beyond a shadow of a doubt. I told you earlier

that there's some controversy among phonologists about the details of distinctive features, although nobody doubts

the basic idea. Well, we're talking about syntax now, and that's one of my own fields of specialization, and i can tell

you that there's a lot of controversy in that area. But every syntactician knows the stuff in this presentation, even

though hann may not agree with it in every detail. Almost all modern syntactic research in some sense or another

starts from the assumptions of the Standard Theory, and that's why it's important to understand this stuff.

162

Beyond that it gets a little controversial. Most would probably agree that the verb speaking

should be grouped with to that quiet boy; some would claim that the auxiliary is should be

grouped with the verb before it gets grouped with anything else, while others would prefer to

leave it for the last. I'm going to go with the latter solution.

[[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is [speaking [to [that quiet boy]]]]

OK, now we have a diagram for the entire sentence. And now perhaps you can see why this type

of diagram is called a tree diagram.

2

The important thing is having this visual diagram of the

organization of the sentence. Every one of the points where two lines meet or one line branches

off from another is called a node. The ends down here, each one corresponding to a single

word, are called nodes too; specifically, they're called terminal nodes.

But we're not done. It's not enough to simply identify which words go with which other words at

what level. We also need to recognize that there are different kinds of words here. We would

all agree that girl, boy, and barrette are the same kind of word they're nouns while

speaking is a verb. So we can label them as follows, using the abbreviations N and V for

noun and verb. We shall also treat the and that as the same kind of word, which we can

call determiner and abbreviate DET. To and with are prepositions, which we abbreviate

P. Blue and quiet are both adjectives, which we abbreviate A; and we're going to give is

the label AUX, for auxiliary.

DET N P DET A N AUX V P DET A N

[[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is [speaking [to [that quiet boy]]]]

OK, so we've labelled all the individual words according to their parts of speech. But what about

these other constituents, these other nodes? They get labels too. First of all, every one of them

is considered a phrase, and that's part of their label. The two phrases the blue barrette and that

quiet boy are called noun phrases on the basis of the substitution test discussed in the previous

chapter; since they can occupy the same syntactic position as simple nouns like dimples or John

as in (1), then by the terms of the substitution test they must belong to the same syntactic category,

or at least have something in common. So since the blue barrette and that quiet boy can be

substituted for simple nouns, we conclude that they partake of the nature of nouns and so we call

them noun phrases or NPs. We can write NP on these nodes here.

(1) The girl with dimples is speaking to J ohn.

2

Even though it's an upside-down tree!

163

NP NP

DET N P DET A N AUX V P DET A N

[[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is [speaking [to [that quiet boy]]]]

Note that the longer phrase the girl with the blue barrette also qualifies as a noun phrase. Simi-

larly, the entire phrase beginning with speaking can be replaced by a single verb; in fact, speak-

ing can exist by itself without anything following it, without any object or modifier; The girl is

speaking is a perfectly good English sentence. Or we could replace it with sleep, or any one

of a number of intransitive verbs. So according to the substitution test we must recognize that

this whole phrase shares some quality with lexical verbs, and so we call this thing a verb phrase

or VP.

NP VP

NP NP

DET N P DET A N AUX V P DET A N

[[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is [speaking [to [that quiet boy]]]]

What about the phrases with the blue barrette and to that boy? This is a little more complica-

ted, but from the point of view of syntax at least phrases like these are generally labelled prepo-

sitional phrases or PPs. We don't have time in this class to go into the controversial issues sur-

rounding this label; we'll accept the general consensus of linguists down through the centuries

and call these things PPs.

What about the whole sentence? Well, obviously, it's a sentence, and that's usually abbreviated

S. The only problem with that abbreviation is that the label S is used not only of simple sen-

tences like this one but of all clauses, including subordinate clauses like the ones in (2). Now

obviously, while they go to school in the morning is not a complete sentence. But it's a clause,

with a subject and a verbal predicate and so on, and in modern syntactic research there is a con-

vention that clauses are labelled S whether they are complete sentences or not. It's a conven-

tion i'm not entirely happy with, but that's the way it is.

(2) [

S

[

S

While they go to school in the morning], [

S

the girl will speak to that boy]]

So now we have a complete tree-diagram of this sentence. In the process of erecting this diagram,

we have organized this sentence into different kinds of categories and thereby provided a struc-

ture for the sentence; we call this a phrase-structure diagram.

3

3

Iin syntactic research we often abbreviate trees; if for instance we are only talking about a particular NP within a

sentence and not about the contents of that NP, we often don't bother spelling out those details. But it's worth

knowing that they're there even so.

164

S

NP VP

PP PP

NP NP

DET N P DET A N AUX V P DET A N

[[[The girl] [with [the blue barrette]]] is [speaking [to [that quiet boy]]]]

Phrase-Structure Rules

What we've just done is draw up a phrase-structure tree-diagram analyzing a particular sentence.

It's time now to move on to a broader perspective and to consider how such tree-diagrams are

built in general. Remember, one thing we're concerned about is that while some combinations

of words are grammatical in a given language others are not, and we need some way of distin-

guishing between grammatical and ungrammatical strings.

What syntacticians have established is that, in a particular language, there are certain general

patterns to the way tree-diagrams are organized. These patterns are often referred to as phrase-

structure rules, or, as that phrase is usually abbreviated, PS-rules. It's important to understand

right away that these are not rules like the ones that may have run your life when you were in

grade school or the laws that provide the structure for a civilized society. A rule or law of that

sort says something like It is illegal to drive down a street on the left-hand side; if a policeman

catches you doing so, you will have to pay a fine. No, when we're talking about PS-rules, we're

talking about something more like a law of nature the sort of thing that says, If you drive

down a street on the wrong side, you may be hit by another car, and both cars will be damaged.

A PS-rule is a statement about what is, and is not, a possible syntactic structure in a given language.

And the way we find out what the PS-rules of a given language are is basically the same way we

find out anything in science: We look at the evidence (in this case, actual sentences and tree-

diagrams of those sentences) and try to recognize the patterns that describe the evidence.

Let's start by figuring out what PS-rules describe this tree-diagram. Starting at the top, we've got

an S node which is dominating, as we say, three other nodes, an NP node, an AUX node, and a

VP node. We can write this out as in (3). A bit of terminology here. Syntactic constituents are

almost always spoken of with feminine imagery; i don't know why, nobody's ever been able to

give me a good explanation as to why; but in a PS-rule, the thing on the left side of the arrow is

called the mother, and the things on the right side are called its daughters. It's important to un-

derstand that, in a proper PS-rule, there can be only one mother, though in principle there can be

any number of daughters. Note that a typical PS-rule says two things: 1 It states what daughters

a constituent may have, and 2 It states what order they can come in.

(3) S NP AUX VP

Now, the rule in (3) mentions AUX. And certainly, as we have defined the term, the sentence

The girl with the blue barrette is speaking to that quiet boy does include an AUX constituent.

But is this really necessary? Does every sentence in English include an AUX? What about the

sentences in (4)? Let's grant that AUX appears to be an optional constituent. The way we re-

present optional constituents in a PS-rule is to enclose them in parentheses, so we can amend the

rule as in (5) by putting AUX in parentheses: (AUX).

165

(4) a. Sam came to school yesterday.

b. Terry likes chocolate.

c. Hilary reads a lot of books.

(5) S NP (AUX) VP

Let's move on to the next level. Our tree-diagram include three NPs. We can describe each of

them by one of the rules in (6ab). Obviously, the adjective and the PP are optional, so we can

put them both in parentheses as in (6c). What about the DET? Is it necessary? Although arti-

cles aren't as optional in English as in a lot of other languages, it must be admitted that the NPs

in (6df) are perfectly good NPs and therefore that articles are to someextent optional in English.

So we can put that in parentheses too, as in (6g).

(6) a. NP DET N PP

b. NP DET A N

c. NP DET (A) N (PP)

d. [

NP

Dogs] do [

NP

tricks].

e. [

NP

I] have [

NP

doubts] about [

NP

that].

f. Does [

NP

air] move [

NP

things]?

g. NP (DET) (A) N (PP)

Now, it's possible to have an NP with several adjectives, as in (7). The 3 adjectives in this NP

are independent of each other; each one could occur by itself, and they could occur in any order.

In order to allow for an unlimited number of optional adjectives, syntacticians make use of a

notational convention involving an asterisk, as in (8). Note that this asterisk is different than the

asterisk used to indicate ungrammaticality. In technical terms, we don't actually call this thing

an asterisk at all; we call it a Kleene star. And it means as many as you like, including none.

(7) a large fierce black dog

(8) NP (DET) (A)* N (PP)

Now let's talk about the VP. This particular VP, speaking to that quiet boy, can be described

by the rule in (9). But obviously not all of this is necessary. It's possible, isn't it, for a verb phrase

to consist of a simple verb all by itself, as in (10)? So the PP should really be in parentheses.

On the other hand, there are lots of transitive verbs taking NP objects, and those objects have to

be included in this rule somehow. But where should they be fit in? Remember, the PS-rule for-

mat we're working with specifies not only the possible daughters of a given category but the order

they may come it. If we have both an NP object and a PP in a VP, where do they occur in relation

to each other? Look at (11). This suggests that an NP object has to come between the verb and

a PP, doesn't it? So it looks like we should insert an optional NP between the verb and the PP in

(9), doesn't it? But should it be just one NP? Look at (12). Some English verbs can take two

NP objects. So our VP rule should really be something like (13).

(9) VP V PP

(10) a. The owl slept.

b. The horse ran.

(11) a. filled the box to the brim

b. *filled to the brim the box

(12) a. gave the baby a ball

b. read me a story

(13) VP V (NP) (NP) (PP)

166

There are two PPs in our sentence the girl with the blue barrette is speaking to that quiet boy,

and both of them can be described by the PS-rule in (14). I don't think i need to say anything

more about that. The fact that the NPs the blue barrette and that quiet boy each have a cer-

tain amount of internal structure is covered by the NP rule in (6b).

(14) PP P NP

I've already mentioned adjectives, in connection with the introduction of the Kleene star notation.

But now it's time to talk about adjective phrases, or APs. Now in the sentence we began this

chapter looking at there are merely two adjectives, separate from each other, so even if we were

to regard each of these as actually an AP (which from the point of view of syntactic theory would

actually be quite reasonable) they would be extremely simple APs, each consisting of a single

word, a single adjective and nothing else. But obviously it's possible for APs to be more complex

then that. Adjectives, which modify nouns, can themselves be modified by adverbs as shown in

(15). In fact, it should be noted that adverbs modifying adjectives (or verbs, for that matter) may

themselves be modified by other adverbs, adverbs of a peculiar type referred to as degree adverbs,

as shown in (16), so we need to be able to define adverb phrases or ADVPs as in (17). And

like NPs and VPs APs can also include PPs as in (18); it is even possible for an AP to be modified

by a whole clause as in (19). So in order to describe all these possibilities we need a PS-rule

like the one in (20).

(15) a. very tired

b. especially kind

c. randomly scattered

(16) a. [very randomly] scattered

b. speak [too quietly]

(17) AdvP (Deg) Adv

(18) a. very tired [of the ride]

b. kind [to his mother]

c. proud [of her daughter]

(19) That dog is [so fierce that nobody can get within 5m of him without his barking

viciously and tugging at his chain].

(20) AP (ADVP) A (PP) (S)

Heads, Complements, Modifiers

There is something very important to notice about the PS-rules in (619). A noun phrase (NP)

always includes a noun (N); a verb phrase (VP) always includes a verb (V); a prepositional phrase

(PP) always includes a preposition (P), an adjective phrase (AP) always includes an adjective

(AP), etc. This may seem obvious at a certain level, but it's worth taking note of; it is, in fact, a

fundamental assertion of modern syntactic theory. With few exceptions, every phrase must in-

clude a head, a word whose own category defines the category of the entire phrase. Every NP is

assumed to be headed by a noun, every VP by a verb, etc.

The other constituents within a phrase, the non-heads, can be classified into two types. Some of

them are complements. Please don't confuse this word with compliments; they're spelled slightly

differently, though for most English-speakers they are virtually indistinguishable in pronunciation.

167

A compliment () is a statement of praise or appreciation. A complement () is something

that completes something else. In grammar, it's understood that some words, by their very nature,

4

require certain other kinds of constituents in order to make sense. This is most obvious in the case

of verbs. Every human language has the distinction between transitive () and intransitive

() verbs. Intransitive verbs like sleep in (21a) don't need anything else and can form a

VP all by themselves. Transitive verbs like see in (21b) require complements of some kind.

What kind of complement(s) a particular verb requires varies over a fairly wide range. Some

verbs, like see, are content with a single NP. Some, like consider in (21c), can take a pair of

NP complements. Some, like talk in (21d), take PP complements. Some, like hope in (21e),

take whole clauses.

(21) a. The baby slept.

b. We saw the Purple Bridge.

c. Many people consider Sun Yat-Sen a great man.

d. I talked to your sister.

e. We hope you will be able to come tomorrow night.

The kinds of complements that a particular head requires are referred to collectively as that word's

valency or subcategorization frame; we can say that a transitive verb like see or talk subca-

tegorizes for an NP complement, or a PP complement, or whatever.

It isn't only verbs that have subcategorization frames. Prepositions, almost by definition, require

NP complements.

5

Nouns and adjectives can also take complements, usually in the form of PPs,

and some seem to require them, at least in certain contexts or usages; cf. argument, purchase,

or belief in (22) or afraid in (23). Such details of valency usually need to be specified in a

word's lexical entry.

(22) a. Todd had an argument with J oe about the purchase of a new car.

b. Elmer's belief that the Earth is flat is not amenable to any rational refutation.

(23) a. Morgan's little brother is afraid of the dark.

b. Hortense is afraid that some of the porcupines might get hurt.

Non-head constituents that are not complements, i.e. are not called for the head's subcategoriza-

tion frame, are usually grouped under the general label modifiers. These include adjective

phrases in NPs and adverb phrases in VPs and APs.

Transformations

The PS-rules we've been discussing so far can describe or generate sentences like those in (24).

They will also generate sentences like those in (25). But they will not, by themselves, account

for the fact that fluent users of English tend to regard each of the sentences in (25) as being rela-

ted in some way to the corresponding sentence in (24). And yet, as noted at the end of the pre-

vious chapter, this kind of relationship is one of the things syntactic theory is supposed to be

able to account for.

4

Which has a lot to do with what they mean, though that's not enough by itself to explain their behaviour; consider,

for instance, the pair of English verbs talk and tell. You can either tell a person something or tell something to

a person, but you can only talk you can only talk to a person about something.

5

Indeed, i'm inclined to regard prepositions in languages like English as merely transitive adverbs, adverbs that

happen to require NP complements.

168

(24) a. The girl gave a toy to the baby.

b. The student was reading a book.

(25) a. The girl gave the baby a toy.

b. The book was read by the student.

Furthermore, the PS-rules we've developed so far may be able to describe or generate a sentence

like the one in (26a), but they can't account for the sentences in (26bc). And yet, not only are

the strings in (26bc) perfectly good sentences of English, but again, the fluent English user sen-

ses that they are somehow related to the sentence in (26a), and this sense of kinship between

these sentences must be accounted for somehow.

(26) a. The student was reading a book.

b. Was the student reading a book?

c. What was the student reading?

This is, however, one of the areas in which controversy is liveliest in syntactic theory. While all

syntactic theorists agree that it's part of our job to account for relationships like these, we differ

seriously in the means by which we do it or think it should be done. I discuss this issue in greater

depth elsewhere; here i will merely mention that within Noam Chomsky's Standard Theory

these relationships between sentences are typically described by transformations. Basically, a

transformation is a grammatical rule saying that one PS tree may be related to another PS tree

having a certain constituent in a different place; in a very metaphorical sense, the transformation

can be said to move a constituent from one part of the tree to another; i've indicated this by the

arrows in (27). Syntacticians working in the Standard Theory are concerned to identify what

transformations are possible or impossible within a given language, or within the class of all

languages generally, and how they work.

(27) a. The girl gave [a toy] to [the baby]. The girl gave [the baby] [a toy] to .

b. The student was reading a book. Was the student reading a book?

c. [The student] read [the book]. [The book] was read by [the student].

Constituent-Order Typology

You will perhaps remember that typology is a favourite subject of mine. I spoke to you in Chapter

1 about the typology of inflexional morphology. Later, i spoke about the typology of phonemes

and segments in human speech, and later still about the typology of writing systems. Well, there's

a typological approach to syntax too. Typically, it has to do with the order of constituents within

the typical sentence.

This is sometimes referred to as Word Order Typology, but i insist on referring to it as Con-

stituent Order Typology. The things that make up a sentence are constituents. Some con-

stituents are single words, but some are phrases. When people talk about word order, whether

in English or J apanese, they're usually thinking about sentences like (28), in which at least in

one sense, remembering our discussion earlier about what is or is not a word there are only

three words, one each for the subject, object, and verb.

169

(28) a. J ohn saw Sally.

b. Taroo-ga Mariko-o yonda.

Taroo saw Mariko.

But we all know that subjects and objects can be NPs made up of many words as in (29). These

things aren't words, they're extremely long and complex phrases, and yet when linguists talk about

word order, they're very often actually talking about things like this. I and a few other linguists

have complained about this on occasion, in public and in print. What we're really talking about

at this point is the order of constituents within sentences; later on we'll have something to say

about the order of words, and other constituents, within phrases.

(29) a. [

NP

The fine upstanding young fellow who regularly spends his Saturdays building

houses for poor people] saw [

NP

the intelligent and beautiful young princess who

was really getting irritated at the way everybody stared at her.]

b. [

NP

Kare-no okaasan-ga genki-datta koro-no Taroo-ga] [

NP

Mariko-ga kare-ni

okutta tegami-o] mada yonde inai.

Taroo under the circumstances of his mother being well =At the time his mother

was well, Taroo had not read the letter Mariko sent to him.

At the broadest level, syntactic typology is concerned with the order of what are sometimes called

the major sentence constituents.

6

These are the subject (), the object (), and the verb

(). For convenience, we usually ab-breviate these S, O, and V. And the basic question in

syntactic typology at this level is: Does a given language prefer a specific order of these consti-

tuents, and if so which is it? Those of you with some math background may be able to figure

out that there are logically six possibilities, as shown in (30).

(30) SOV SVO VSO

VOS OVS OSV

Alright, let's start with the languages we know best. Where do you think Chinese belongs in this

list? What does Chinese prefer among the six possible orderings of subject, object, and verb?

Right. What about English? Right, they both prefer SVO. What about Japanese? Do any of you

know enough about J apanese to answer this question? J apanese prefers SOV; so does Korean,

so i'm told. Sanskrit and most of its modern relatives in India go in the SOV slot too. I'm told

the same is true of Tibetan and Amharic, a language of Ethiopia. German too, although it's not

obvious at first. Statistically, most German sentences are SVO, at least on the surface. But there

is evidence that they're really SOV under the surface. The behaviour of complex verbs, and of

all verbs in subordinate clauses, gives that away.

Most of the other major European languages, such as Italian, Russian, Finnish, etc. seem to be-

long in the SVO camp, as do Vietnamese and Hausa, a language of central Africa. There's one

small group of European languages, the Celtic family, whose members prefer VSO: Welsh, Irish,

Breton. Arabic belongs here too. So does Rukai; anybody here ever hear of the Rukai language?

It's native to this island. Maori, Hawaiian, and Tongan are also VSO languages.

Rukai, Maori, Hawaiian, and Tongan are members of a large family of languages called the Aus-

tronesian family, most of whose members prefer to put the verb at the beginning of the clause.

Among the Austronesian family are a few VOS languages, notably Fijian and Malagasy.

6

though some of us prefer the German term Satzglieder.

170

In the 1970's a few languages were found down in the Amazon river basin in South America that

as far as we can tell prefer either OSV or OVS order. These are languages like Hixkaryana,

Jamamadi, Apurina, and Makusi. So as you can see in (31), every single possible preferred order

of subject, object, and verb is represented among the world's languages; for every conceivable

order, there are at least a few human languages that prefer that order.

(31) SOV J apanese, Korean, Sanskrit, Hindi, Tibetan, Amharic, German

SVO Chinese, English, French, Italian, Russian, Finnish, Vietnamese, Hausa

VSO Welsh, Breton, Irish, Arabic, Rukai, Maori, Hawaiian, Tongan

VOS Fijian, Malagasy

OVS Hixkaryana, Makusi

OSV J amamadi, Apurina

But by how much? Notice how much longer the first three lines in (31) are than the last three.

Over 75% of the world's languages prefer either SOV or SVO order; VSO accounts for another

1015%.

7

That's about 90% for only half the logical possibilities; the other three account for

only about 10% at most of human languages.

Why? What is it about these orders that makes them so much favoured over these others among

human languages? Notice that the one thing they have in common is that they put the subject be-

fore the object. On the basis of this evidence, linguists believe that there is a strong preference

among human languages for putting the subject before the object, even stronger than putting the

subject before the verb though that seems to be important too.

8

We suspect that this says some-

thing important about how the human mind works, but we don't yet know what.

The extreme rarity of object-before-subject languages, and OSV or OVS languages in particular,

has led some science fiction writers to use these orders deliberately in order to make some of their

characters sound especially alien. I don't know how this comes across in the Chinese-language

version of Star Wars (), but in the English original the Jedi Master Yoda routinely comes

out with sentences like those in (32). And when the first Star Trek movies were being made in

the late 70's and early 80's, someone connected with that project designed a language for Klingon

characters to speak, and deliberately made it an OVS language. Even though most of us can't

understand a word the Klingons say (and many of us probably wouldn't want to!), the idea seems

to have been to make their language as unlike human language as possible while still being re-

cognizable as a language.

(32) Yoda-Speak (examples of OSV)

a. [Help you] I can.

b. [Strong with the Force] you are.

c. [Your father] he is.

d. When [900 years] you reach, [look as good] you will not!

7

The VSO line in (31) may look as long as those above it, but that's because i beefed it up for local interest; here on

Taiwan, at the edge of the Pacific Ocean, there are an awful lot of VSO languages not too far away.

8

Personally, i've gotten rather curious about the dynamics of VOS languages, which is one reason i've gotten inter-

ested in studying Austronesian languages. But as you can see, even among Austronesian languages VOS langua-

ges are in the minority.

171

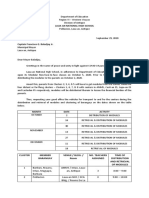

Fig. 8.1 Make Sure Your Grammar Teacher is Using the Right Grammar!

We've looked at the order of the major clause constituents, but there's also some interesting things

to be said about the order of words within clauses. Let's look first at the order of words within

NPs; in (3334) i've given some NPs from English and French, and in each case i've underlined

the nouns to clearly distinguish them from their modifying adjectives, etc. You're probably all

aware that English prefers to put adjectives before nouns, as in (33ab); however, it's possible in

English to put long adjective phrases after nouns, as in (33cd). French is kind of the opposite

of English in this respect, in that it prefers to put adjectives after nouns, as you can see from (34a

b). However, there are some NPs in which the adjective comes before the noun; i've given some

examples in (34cd). This situation is not, note, the exact equivalent of the situation in English.

It isn't that unusually long adjective phrases in French typically precede nouns while those in Eng-

lish typically follow them; the adjective phrases in (34cd) aren't particularly long, in fact you'll

notice that the adjectives in (34bc) are essentially the same adjective, it's just that for some reason

this adjective goes after the head noun if it's describing a house but before the head noun if it's

describing a boy.

(33) N-A order in English

a. cold water c. nature red in tooth and claw

b. a big house d. a book hard to come by

(34) N-A order in French

a. l'eau froide cold water c. un grand garon a big boy

b. une maison grande a big house d. une jolie jeune fille a pretty young girl

In Chinese, however, as far as i can tell all modifiers, no matter how long and complex they are,

have to go before the words they modify. Witness the phrases in (35), as compared with their

English translations.

(35) a. [] people [who can speak Chinese]

b. [] these characters [that your daughter wrote]

c. [] the two owls [sitting on my computer]

d. [] two cute girls [with umbrellas]

Languages can differ in the order of constituents within PPs; cf. (36). Languages like J apanese

in which the NP object of a PP comes first are often said to have postpositions rather than pre-

positions, since the elements in question come after their complements rather than before. Lin-

guists often talk in general about adpositions when they don't want to specify which side of

the complement these things show up. In some languages, like English and French, the adposi-

tions are all prepositions, coming before their complements. In others, like J apanese and Hindi,

they're all postpositions. And some languages, like Amharic, have both.

172

(36) a. English: from Tokyo

b. J apanese: Tokyo kara

Syntactic typologists are particularly interested in the possibility of making generalizations about

the order of various kinds of constituents. It's been noticed that the order of the head and the

complements in one particular kind of phrase is often repeated in other kinds of phrases. For

instance, in J apanese and Hindi the verb comes at the end of the VP, after its objects, the adpo-

sitions are postpositions, coming after their NP complements, and head nouns come at the ends

of NPs, after all their modifiers, while in English the verb comes before its object, the adpositions

are all prepositions, coming before their NP complements, and the head noun comes before any

PP modifiers. However, while German is basically a verb-final language, it has prepositions in-

stead of postpositions. And although English nouns precede PP modifiers, they normally follow

adjective modifiers; French is rather more consistent in that it puts the verb before its object,

preposes adpositions, and normally puts both adjective and PP modifiers after nouns, although

as we have seen even in French the adjective may sometimes precede the noun it modifies. And

Chinese differs from both English and French in this respect, while agreeing with both of them

in prefering to put the verb in the middle of the clause; in fact, in many respects with regard to

constituent-order typology Chinese behaves a lot more like the languages of India, most of which

are SOV languages. Syntactic theorists and typologists spend a lot of their time studying issues

like this, trying to make sense out of them.

Back in Chapter 1 i said that languages can be classified in many different ways and that typology

is the study of these different ways. Now that i've introduced both morphological and syntactic

typology, it's worthwhile to compare these two approaches a little bit. Back in Chapter 1 i noted

that languages could be classified into several different categories (e.g. isolating, agglutinatng,

sythetic) on the basis of how much inflexional morphology they have and how it works. In this

chapter, i've noted that languages can also be classified in terms of which order of the major sen-

tence constituents (subject, object, verb) they prefer. As can be seen from Fig. 8.2, these different

approaches to classification yield different results. Different linguists are going to be interested

in different things and therefore in different classifications; a morphologist is probably going to

be more interested in the difference between isolating and inflecting languages, while a syntac-

tician is probably going to be more interested in the difference between verb-final and verb-initial

languages, or between verb-medial and verb-peripheral languages.

SOV SVO VSO

isolating Burmese Chinese, Vietnamese Samoan, Hawaiian

agglutinating

Turkish, J apanese,

Basque

Hungarian, Finnish,

Swahili

synthetic Latin, Sanskrit Greek, Russian Irish, Arabic

Fig. 8.2 Different Typological Approaches

But beyond that, it is possible to look at a table like the one in Fig. 8.2 or, preferably, a more

complete table with a lot more languages listed in it and pick out those languages that share

both a syntactic type and a morphological type. One might be interested in examining specifically

agglutinating SOV languages, say, or inflecting VSO languages. There might be something very

interesting and worth saying about languages that meet such pairs of typological criteria. And

173

one could, of course, make such a complex classification even more complex by bringing in, e.g.,

phonological considerations such as constraints on syllable structure which languages allow

closed syllables (syllables ending in consonants)? Which languages allow consonant clusters?

It's when they find the business of language-classification interacting at such different levels that

typologists often find their work getting most interesting.

174

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Demo Lesson For MindsetDokument7 SeitenDemo Lesson For MindsetAslı Serap TaşdelenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentence, Utterance, Proposition Andsemantic Roles: SemanticsDokument17 SeitenSentence, Utterance, Proposition Andsemantic Roles: SemanticsZUHRANoch keine Bewertungen

- Elements of A Short StoryDokument12 SeitenElements of A Short StoryCayo BernidoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1-Investigate and Write What's Grammar. Give Details.: Classification of VerbsDokument7 Seiten1-Investigate and Write What's Grammar. Give Details.: Classification of VerbsEnrique RosarioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Korean ParticlesDokument8 SeitenKorean ParticlesBellaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English GrammarDokument78 SeitenEnglish GrammarPalaniveloo SinayahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Say What You Mean!: Move up the Social and Business Ladder--One Perfect Word After Another.Von EverandSay What You Mean!: Move up the Social and Business Ladder--One Perfect Word After Another.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sentence and List StructureDokument8 SeitenSentence and List StructureThomy ParraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chomsky's TGG - Part of Theses by DR Rubina Kamran of NUMLDokument15 SeitenChomsky's TGG - Part of Theses by DR Rubina Kamran of NUMLmumtazsajidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 2 ForegroundingDokument12 SeitenTopic 2 ForegroundingBehbud MuhammedzadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apostrophe Catastrophe: And Other Grammatical GrumblesVon EverandApostrophe Catastrophe: And Other Grammatical GrumblesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grammatical Structures of English Module 02Dokument53 SeitenGrammatical Structures of English Module 02Fernand MelgoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Briefest English Grammar and Punctuation Guide Ever!Von EverandThe Briefest English Grammar and Punctuation Guide Ever!Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer in EnglishDokument69 SeitenReviewer in EnglishReniel V. Broncate (REHNIL)Noch keine Bewertungen

- 4th UbdDokument8 Seiten4th UbdRuth SameNoch keine Bewertungen

- Albe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsDokument5 SeitenAlbe C. Nopre Jr. CE11KA2: VerbalsAlbe C. Nopre Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Parts of SpeechDokument19 SeitenParts of Speechleona dao100% (3)

- Easy Guide On Omitting English Relative Pronouns "Which, Who, and That"Dokument12 SeitenEasy Guide On Omitting English Relative Pronouns "Which, Who, and That"BondfriendsNoch keine Bewertungen

- CASEDokument58 SeitenCASEsuryaNoch keine Bewertungen

- English NotesDokument14 SeitenEnglish NotesFatima RiveraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambiguity in SemanticsDokument4 SeitenAmbiguity in SemanticsNur Mya Bazyla100% (1)

- File - 20210916 - 132211 - Lex - Unit 1Dokument16 SeitenFile - 20210916 - 132211 - Lex - Unit 1Tường VyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Semantic PrepositionsDokument8 SeitenSemantic Prepositionsmadutza01100% (1)

- Prepositions: A Complete Grammar Guide (With Preposition Examples)Dokument37 SeitenPrepositions: A Complete Grammar Guide (With Preposition Examples)Adelina Elena GhiuţăNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marija Brala: ''Inside Babel''Dokument72 SeitenMarija Brala: ''Inside Babel''Ajiram ĆičiliNoch keine Bewertungen

- VocabularyDokument137 SeitenVocabularyellen abesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Really Simple English GrammarDokument199 SeitenReally Simple English GrammarMateus Scherer CardosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- LEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDDokument40 SeitenLEC - Noun Phrase, An I, Sem. 1 IDlucy_ana1308Noch keine Bewertungen

- Session Notes 19-04-26 PDFDokument4 SeitenSession Notes 19-04-26 PDFMichael SchiffmannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Attacked, The Subject Is John, But John Is Certainly Not The 'Doer' of The Attacking. Again, Not All Sentences, Even RelativismDokument10 SeitenAttacked, The Subject Is John, But John Is Certainly Not The 'Doer' of The Attacking. Again, Not All Sentences, Even RelativismTeresa RoqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eng. Lesson NoteDokument5 SeitenEng. Lesson NoteAmos ObanleowoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8tonicity Resumen WellsDokument19 Seiten8tonicity Resumen WellsMoiraAcuñaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bloomfield, L. MeaningDokument6 SeitenBloomfield, L. MeaningRodolfo van GoodmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Isang Dosenang Klase NG High School Students: Jessalyn C. SarinoDokument8 SeitenIsang Dosenang Klase NG High School Students: Jessalyn C. SarinoMary Jane Reambonanza TerioteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 1 - Darun Najah Ramadhan Short CourseDokument20 SeitenChapter 1 - Darun Najah Ramadhan Short CourseMunir MaverickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paper Reference Group 3Dokument12 SeitenPaper Reference Group 3Mega WNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2.1 Chapter 2 - Word Classes - Ballard, Kim. 2013. The Frameworks of English. - ReadDokument37 SeitenUnit 2.1 Chapter 2 - Word Classes - Ballard, Kim. 2013. The Frameworks of English. - ReadJoão FreitasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Understanding the Concepts of English PrepositionsVon EverandUnderstanding the Concepts of English PrepositionsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- All About EnglishDokument111 SeitenAll About EnglishLara Mae Austria100% (1)

- Phrsal VerbesDokument9 SeitenPhrsal Verbeseugeniosiquice963Noch keine Bewertungen

- Module 3 - Lesson 1 - Semantics and PragmaticsDokument18 SeitenModule 3 - Lesson 1 - Semantics and PragmaticsMarielle Eunice ManalastasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syntax Final ProjectDokument24 SeitenSyntax Final ProjectRachditya Puspa AndiningtyasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagramming Sentences - Visuali - Mira SaraswathiDokument28 SeitenDiagramming Sentences - Visuali - Mira SaraswathibhaskarNoch keine Bewertungen

- CHP2 Recognizing Clauses and Clause Constituents - Thompson, 2004Dokument14 SeitenCHP2 Recognizing Clauses and Clause Constituents - Thompson, 2004Karenina ManzanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patterns and VocabularyDokument9 SeitenPatterns and Vocabularyapi-300956632Noch keine Bewertungen

- Radford Chs-2Dokument60 SeitenRadford Chs-2h_e_i_d_iNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thereisa Mental GrammarDokument24 SeitenThereisa Mental GrammarmafistovNoch keine Bewertungen

- TEXTO 4 - Studying SyntaxDokument11 SeitenTEXTO 4 - Studying SyntaxNataly MoyanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Untitled PresentationDokument31 SeitenUntitled PresentationJaden DavisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson 5 RAW Relative PronounDokument15 SeitenLesson 5 RAW Relative PronounMerlito BabantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basic Grammar RulesDokument24 SeitenBasic Grammar RulesAudit Department100% (1)

- Chapter 2Dokument33 SeitenChapter 2Thatha BaptistaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary For Linguistics Mid TermDokument20 SeitenSummary For Linguistics Mid TermAlondra L. FormenteraNoch keine Bewertungen

- SyntaxDokument26 SeitenSyntaxElyasar AcupanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4 - Common Grammar ErrorsDokument8 Seiten4 - Common Grammar ErrorsNika AlejandroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Noun Phrase (I)Dokument7 SeitenNoun Phrase (I)Alina RNoch keine Bewertungen

- English Study GuideDokument68 SeitenEnglish Study GuideKelvin FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Syntax Introduction To LinguisticDokument6 SeitenSyntax Introduction To LinguisticShane Mendoza BSED ENGLISHNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Structure of Noun PhraseDokument11 SeitenThe Structure of Noun PhraseSeffuLeonardJacinto100% (1)

- 12 - The Particle Wa IDokument13 Seiten12 - The Particle Wa IKocourek MourekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Topic 3 Perimeter, Area and VolumeDokument15 SeitenTopic 3 Perimeter, Area and Volumeairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter3 PDFDokument23 SeitenChapter3 PDFairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arahan: Cari Hasil Darab Dan Tukarkan Unit.: 1. 18 CM X 7 MM 4. 4356 M X 5 KMDokument1 SeiteArahan: Cari Hasil Darab Dan Tukarkan Unit.: 1. 18 CM X 7 MM 4. 4356 M X 5 KMairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter5 PDFDokument15 SeitenChapter5 PDFairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 12Dokument34 SeitenLecture 12airies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- m2 WordformationDokument21 Seitenm2 Wordformationairies92100% (2)

- Understanding Nonverbal Communication FInalDokument12 SeitenUnderstanding Nonverbal Communication FInalairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Isl Week 3Dokument3 SeitenIsl Week 3airies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Language and Culture in International Legal CommunicationDokument17 SeitenLanguage and Culture in International Legal Communicationairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Combined Language StructureDokument6 SeitenCombined Language Structureairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- 2 KindsDokument3 Seiten2 Kindsairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- App DifferentiationDokument3 SeitenApp Differentiationairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Engineering MathDokument29 SeitenEngineering Mathairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- Choose The Correct AnswerDokument6 SeitenChoose The Correct Answerairies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- MID Year 3 Paper 1 09Dokument13 SeitenMID Year 3 Paper 1 09airies92Noch keine Bewertungen

- A Brief Journey Through Arabic GrammarDokument28 SeitenA Brief Journey Through Arabic GrammarMourad Diouri100% (5)

- Module Letter 1Dokument2 SeitenModule Letter 1eeroleNoch keine Bewertungen

- An Introduction: by Rajiv SrivastavaDokument17 SeitenAn Introduction: by Rajiv SrivastavaM M PanditNoch keine Bewertungen

- EnglishDokument3 SeitenEnglishYuyeen Farhanah100% (1)

- Ifm 8 & 9Dokument2 SeitenIfm 8 & 9Ranan AlaghaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume-Pam NiehoffDokument2 SeitenResume-Pam Niehoffapi-253710681Noch keine Bewertungen

- Revision of Future TensesDokument11 SeitenRevision of Future TensesStefan StefanovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- CH 1 QuizDokument19 SeitenCH 1 QuizLisa Marie SmeltzerNoch keine Bewertungen

- C1 Level ExamDokument2 SeitenC1 Level ExamEZ English WorkshopNoch keine Bewertungen

- Shell - StakeholdersDokument4 SeitenShell - StakeholdersSalman AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Department of Education On Academic DishonestyDokument3 SeitenThe Department of Education On Academic DishonestyNathaniel VenusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Printed by SYSUSER: Dial Toll Free 1912 For Bill & Supply ComplaintsDokument1 SeitePrinted by SYSUSER: Dial Toll Free 1912 For Bill & Supply ComplaintsRISHABH YADAVNoch keine Bewertungen

- DLF New Town Gurgaon Soicety Handbook RulesDokument38 SeitenDLF New Town Gurgaon Soicety Handbook RulesShakespeareWallaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2016 GMC Individuals Round 1 ResultsDokument2 Seiten2016 GMC Individuals Round 1 Resultsjmjr30Noch keine Bewertungen

- D Matei About The Castra in Dacia and THDokument22 SeitenD Matei About The Castra in Dacia and THBritta BurkhardtNoch keine Bewertungen

- Union Bank of The Philippines V CADokument2 SeitenUnion Bank of The Philippines V CAMark TanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elaine Makes Delicious Cupcakes That She Mails To Customers AcrossDokument1 SeiteElaine Makes Delicious Cupcakes That She Mails To Customers Acrosstrilocksp SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Series I: Episode OneDokument4 SeitenSeries I: Episode OnesireeshrajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is Modern Capitalism Sustainable? RogoffDokument107 SeitenIs Modern Capitalism Sustainable? RogoffAriane Vaz Dinis100% (1)

- Developing A Business Plan For Your Vet PracticeDokument7 SeitenDeveloping A Business Plan For Your Vet PracticeMujtaba AusafNoch keine Bewertungen

- Au L 53229 Introduction To Persuasive Text Powerpoint - Ver - 1Dokument13 SeitenAu L 53229 Introduction To Persuasive Text Powerpoint - Ver - 1Gacha Path:3Noch keine Bewertungen

- BCLTE Points To ReviewDokument4 SeitenBCLTE Points To Review•Kat Kat's Lifeu•Noch keine Bewertungen

- EAD-533 Topic 3 - Clinical Field Experience A - Leadership AssessmentDokument4 SeitenEAD-533 Topic 3 - Clinical Field Experience A - Leadership Assessmentefrain silvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Contemporary World Reflection PaperDokument8 SeitenContemporary World Reflection PaperNyna Claire GangeNoch keine Bewertungen

- HumanitiesprojDokument7 SeitenHumanitiesprojapi-216896471Noch keine Bewertungen

- Correctional Case StudyDokument36 SeitenCorrectional Case StudyRaachel Anne CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Land Use and Development in BahrainDokument345 SeitenThe History of Land Use and Development in BahrainSogkarimiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Turtle Walk WaiverDokument1 SeiteTurtle Walk Waiverrebecca mott0% (1)

- Disabilities AssignmentDokument8 SeitenDisabilities Assignmentapi-427349170Noch keine Bewertungen

- Restrictive Covenants - AfsaDokument10 SeitenRestrictive Covenants - AfsaFrank A. Cusumano, Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen