Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Forearm Fractures PDF

Hochgeladen von

Nur Ashriawati Burhan0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

113 Ansichten4 SeitenThe document provides information about adult forearm fractures, including:

- The forearm contains two long bones, the radius and ulna, which form the elbow and wrist joints. A forearm fracture causes pain, swelling, deformity and inability to use the arm.

- Evaluation involves x-rays to determine the fracture pattern and check for nerve/vessel damage or compartment syndrome risk. Nearly all forearm fractures require surgery to restore bone alignment.

- Surgical treatment options are a metal plate and screws, metal rod, or external fixator. The goal is restoring normal bone position and rotation to allow wrist motion. Complications can include infection, compartment syndrome, non-healing or malunion

Originalbeschreibung:

Forearm-Fractures.pdf

Originaltitel

Forearm-Fractures.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe document provides information about adult forearm fractures, including:

- The forearm contains two long bones, the radius and ulna, which form the elbow and wrist joints. A forearm fracture causes pain, swelling, deformity and inability to use the arm.

- Evaluation involves x-rays to determine the fracture pattern and check for nerve/vessel damage or compartment syndrome risk. Nearly all forearm fractures require surgery to restore bone alignment.

- Surgical treatment options are a metal plate and screws, metal rod, or external fixator. The goal is restoring normal bone position and rotation to allow wrist motion. Complications can include infection, compartment syndrome, non-healing or malunion

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

113 Ansichten4 SeitenForearm Fractures PDF

Hochgeladen von

Nur Ashriawati BurhanThe document provides information about adult forearm fractures, including:

- The forearm contains two long bones, the radius and ulna, which form the elbow and wrist joints. A forearm fracture causes pain, swelling, deformity and inability to use the arm.

- Evaluation involves x-rays to determine the fracture pattern and check for nerve/vessel damage or compartment syndrome risk. Nearly all forearm fractures require surgery to restore bone alignment.

- Surgical treatment options are a metal plate and screws, metal rod, or external fixator. The goal is restoring normal bone position and rotation to allow wrist motion. Complications can include infection, compartment syndrome, non-healing or malunion

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 4

A Patient's Guide to Adult Forearm Fractures

Adult Forearm Fractures

Anatomy

Two bones, the radius and the ulna, make up the

forearm. The ulna is larger than the radius at the

elbow and the transfer of force across the elbow

joint occurs from the ulna to the distal humerus (the

upper arm bone). The radius is larger than the ulna

at the wrist and force across the wrist joint occurs

primarily from the distal radius to the carpal bones of

the wrist. The main function of this arrangement is

to allow the radius bone to rotate around the ulna in

order to place the hand either palm up (called supina-

tion) or palm down (called pronation) - and all points

in between. Both the radius and ulna form part of

the elbow joint and the wrist joint. Each bone also

articulates (or moves against) the other at the wrist

and elbow joints.

Signs and Symptoms

A fracture of the forearm causes pain and swelling in the forearm. Because the radius and ulna

are relatively long tubular bones, when they are broken the forearm tends to look deformed or

angulated. You will probably not be able to use

the arm and the forearm will have a tendency

to flop and bend. You may feel the bone frag-

ments shift as you try to use the arm. There is

usually bleeding from the fracture into the tissues

of the forearm causing significant swelling.

The swelling may be extreme leading to one

of the possible complications of this fracture,

a compartment syndrome. A compartment

syndrome occurs when the pressure from the

swelling disrupts the blood supply to the muscles

of one or more "compartments" of the forearm.

When this occurs the muscle tissue may actually

die if the pressure is not relieved. This results in

scarring of the muscles that move the wrist and

fingers and they no longer work as they should.

This is a serious potential complication.

Evaluation

The primary goal of the clinical evaluation of a forearm fracture is to determine the fracture

pattern. There are many variations of forearm fractures including fractures of both the radius and

ulna, fractures of either the radius or ulna, and fractures that include a fracture of one or both

bones combined with a dislocation at the wrist or elbow joint. The fracture pattern will determine

A Patient's Guide to Adult Forearm Fractures

how your surgeon proposes fixing the fracture(s). The

fracture is evaluated by taking several x-rays of the

forearm that include the elbow joint and wrist joint.

Special imaging studies such as a CAT Scan or MRI

Scan are usually unnecessary. Your provider will also

want to make sure that there has been no damage

to the nerves and blood vessels and that there is no

evidence of a compartment syndrome beginning. This

can usually be accomplished with a careful physical

examination.

Treatment

Nearly all forearm fractures require surgery. If the

fracture is an open fracture (also called a "compound"

fracture) there is a surgery that will be necessary immedi-

ately to reduce the risk of infection. An open fracture occurs

when there is a laceration through the skin at the fracture

site. This can be caused by either the ends of the fracture

tearing out through the skin or an external object puncturing

the skin from the outside. If there is evidence that a compart-

ment syndrome is beginning, surgery will be immediately

necessary to relieve the pressure in the muscle compartments

affected; the fracture will be fixed during the procedure as

well.

Nonsurgical

If the fracture is not "open" and there is no concern for a

compartment syndrome, you may be placed in a bulky, long

arm splint to stabilize the arm until surgery can be scheduled.

In some cases, surgery may not be necessary. If the

fracture involves only the ulna and the fracture frag-

ments have not displaced or angulated (meaning that

they remain aligned with the two ends of the fractured

bone together), your surgeon may recommend treating

the fracture with a cast or fracture brace instead of

surgery.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of forearm fractures can be

performed in three ways: a metal plate and screws

along the side of the bone, a metal rod inside the bone

or an external fixator with metal pins through the skin.

A Patient's Guide to Adult Forearm Fractures

Most forearm fractures require Open Reduction and Internal Fixation (ORIF) using a metal plate

and screws. This type of treatment allows the fracture to be fixed anatomically, meaning that

the bones can be restored to their normal position and held there with the plate and screws until

healing occurs. It is important that the radius and ulna

be restored as close as possible to normal to ensure

that the radius can rotate around the ulna. This means

that both the angle and the rotation of the two fracture

fragments needs to be restored to normal in addition

to making sure that the two ends of the bone are back

together. This is best achieved with ORIF using a plate

and screws in most cases.

The intramedullary

rod is not commonly

used to treat forearm

fractures, but in some

special circumstances

it can be used to reduce

the need for making incisions in the forearm. The intramedullary

rod is a metal rod that is placed inside the hollow shaft of a tubular

bone such as the radius or ulna. The metal rod can be inserted

into the bone through a small incision at either the wrist or elbow.

The intramedullary rod is inserted with the aid of a special X-ray

machine called a fluoroscope. The fluoroscope allows the surgeon

to see an X-ray image of the bones on a television monitor and

guide the placement of the intramedullary rod by viewing this

image.

External fixation is not commonly used for forearm

fractures. This type of treatment may be necessary for

open fractures when the risk of infection is high or there

has been loss of bone leaving a gap; for example, when

the fracture is due to a gunshot. The external fixation

device allows the surgeon to place metal pins through

the skin and into the bone fragments away from the

fracture site. These metal pins are then connected to

a metal frame outside the skin. Thus, the fracture is

stabilized, but there are no foreign materials (such as

metal plates) in the fracture site to harbor the infectious

bacteria. The fracture is less likely to develop an infec-

tion of the bone (called osteomyelitis).

Complications

Nearly all fractures can result in damage to nerves and blood vessels and forearm fractures are

no exception. Infection may occur but is rare after ORIF. The risk of infection increases if the

A Patient's Guide to Adult Forearm Fractures

fracture is an open fracture. One of the most dreaded complications of a forearm fracture is the

compartment syndrome discussed above. Your surgeon will monitor the situation carefully during

the first several days and weeks before and after surgery. A special pressure monitoring apparatus

can be used to check the pressure in the muscle compartments if there is concern. If your surgeon

thinks that a compartment syndrome is occurring, then a surgical procedure to relieve the pressure

on the muscles will need to be done immediately.

The fracture fragments may fail to heal; this is

referred to as a nonunion. The fracture fragments may

also heal in an unacceptable alignment; this is called

malunion. Both of these complications may result in

pain, loss of strength and a decreased range of motion

of the shoulder. A second operation may be needed to

treat the complication.

Rehabilitation

Many surgeons do not use a cast or brace after stable

ORIF of forearm fractures. Rehabilitation will begin

once your surgeon feels that the fracture is stable

enough to begin regaining the range of motion in your

wrist and elbow. Your rehabilitation program will be

modified to protect the fixation of the fracture fragments. Your surgeon will communicate with

your physical therapist to make sure that your rehabilitation program does not risk causing the

fixation to fail. If the surgeon feels that the fixation is very solid, you may be able progress your

program quickly; if the fixation is not so solid, the speed at which you progress may need to be

slowed until more healing occurs. The prognosis for simple forearm fractures is generally excel-

lent. For those more complex forearm fractures that include dislocations of either the elbow or the

wrist, there is more risk of loss of range of motion in either the elbow or wrist.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Hip Fractures-Orthoinfo - AaosDokument9 SeitenHip Fractures-Orthoinfo - Aaosapi-228773845Noch keine Bewertungen

- Principles and Management of Acute Orthopaedic Trauma: Third EditionVon EverandPrinciples and Management of Acute Orthopaedic Trauma: Third EditionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acromioclavicular Joint Injury, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsVon EverandAcromioclavicular Joint Injury, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Simple Guide to Ankle Dislocation, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsVon EverandA Simple Guide to Ankle Dislocation, Diagnosis, Treatment and Related ConditionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Forearm Fractures, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsVon EverandForearm Fractures, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scaphoid Fracture, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsVon EverandScaphoid Fracture, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Avascular Necrosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsVon EverandAvascular Necrosis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (2)

- Wrist Fractures: Musculoskeletal TraumaDokument4 SeitenWrist Fractures: Musculoskeletal TraumaDewina Dyani Rosari IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Lect 8 Lower Extremity Fracture 2Dokument22 SeitenLect 8 Lower Extremity Fracture 220-221 Crisny Novika Yely Br. HutagaolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To OrthopaedicsDokument42 SeitenIntroduction To Orthopaedicsgus_lions100% (1)

- Fracture of The Talus and Calcaneus NickDokument43 SeitenFracture of The Talus and Calcaneus NickTan Zhi HongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thoracolumbar FracturesDokument29 SeitenThoracolumbar FracturesFernaldi Anggadha100% (1)

- B 756 Vertebris GB III10Dokument44 SeitenB 756 Vertebris GB III10Lukasz Bartochowski100% (1)

- Dislocation: Muhammad ShahiduzzamanDokument30 SeitenDislocation: Muhammad ShahiduzzamanAliceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Proximal Femoral NewDokument34 SeitenProximal Femoral NewHimanshu HemantNoch keine Bewertungen

- DislocationDokument46 SeitenDislocationShaa ShawalishaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Achilles Tendon RuptureDokument19 SeitenAchilles Tendon Ruptureapi-509245925Noch keine Bewertungen

- AO Trauma Vol.2Dokument100 SeitenAO Trauma Vol.2Cujba GheorgheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopedic: Dislocations of The Hip JointDokument16 SeitenOrthopedic: Dislocations of The Hip JointAnmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fracture of Tibia and FibulaDokument31 SeitenFracture of Tibia and Fibulaunknown unknown100% (1)

- Management of FractureDokument20 SeitenManagement of FractureHitesh RohitNoch keine Bewertungen

- Developmental Hip Dysplasia and DislocationDokument51 SeitenDevelopmental Hip Dysplasia and Dislocationandi firdha restuwatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Humeral Shaft FractureDokument82 SeitenHumeral Shaft FractureYoga AninditaNoch keine Bewertungen

- SCOLIOSISDokument19 SeitenSCOLIOSISEspers BluesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Club Foot-Dr J SahooDokument9 SeitenClub Foot-Dr J SahooSheel Gupta100% (1)

- Lower Limb Fracture..MeDokument142 SeitenLower Limb Fracture..MeWorku KifleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supracondylar FractureDokument10 SeitenSupracondylar FractureHemanath SinnathambyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cast and Splint Immobilization - Complications PDFDokument11 SeitenCast and Splint Immobilization - Complications PDFcronoss21Noch keine Bewertungen

- Classification AO PediatricDokument36 SeitenClassification AO PediatricdvcmartinsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spinal Trauma: Causes of Cervical Spinal Injury (UK)Dokument16 SeitenSpinal Trauma: Causes of Cervical Spinal Injury (UK)Mohamed Farouk El-FaresyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hip Joint DislocationDokument59 SeitenHip Joint DislocationAnonymous P5FDn81yNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopedic SurgeryDokument53 SeitenOrthopedic SurgeryGeorgeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Oh My Painful FOOT!!!: Plantar FasciitisDokument20 SeitenOh My Painful FOOT!!!: Plantar FasciitisAsogaa MeteranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knee DislocationDokument39 SeitenKnee Dislocationdr_s_ganesh100% (1)

- AAOS - Clubfoot - ADCDokument17 SeitenAAOS - Clubfoot - ADCMulya ImansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trochanteric #Dokument20 SeitenTrochanteric #Prakash AyyaduraiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coxitis TB Hip KneeDokument26 SeitenCoxitis TB Hip KneefajarvicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Patellar FractureDokument25 SeitenPatellar FractureSyafiq ShahbudinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ankle Arthrodesis - Screw FixationDokument26 SeitenAnkle Arthrodesis - Screw FixationChristopher HoodNoch keine Bewertungen

- 42 - Orthopedic PrinciplesDokument14 Seiten42 - Orthopedic PrinciplesJeffrey Ariesta PutraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Patellofemoral Chondral InjuriesDokument24 SeitenManagement of Patellofemoral Chondral InjuriesBenalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopedic InjuriesDokument27 SeitenOrthopedic InjuriesvikramNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTEVDokument61 SeitenCTEVSylvia LoongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Orthopedic Inpatient Protocols: A Guide to Orthopedic Inpatient RoundingVon EverandOrthopedic Inpatient Protocols: A Guide to Orthopedic Inpatient RoundingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Musculoskeletal TraumaDokument103 SeitenMusculoskeletal TraumaJona Kristin EnclunaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Knee Ligament InjuriesDokument40 SeitenKnee Ligament InjuriesdrorthokingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Femoral Neck FracturesDokument8 SeitenFemoral Neck FracturesMorshed Mahbub AbirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Lumbar Spinal StenosisDokument11 SeitenManaging Lumbar Spinal StenosismudassarnatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elbow TraumaDokument62 SeitenElbow Traumadrcoolcat2000Noch keine Bewertungen

- Arm:Leg Fracture PDFDokument11 SeitenArm:Leg Fracture PDFHannaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malleolar Fractures - Handout PDFDokument14 SeitenMalleolar Fractures - Handout PDFAlin Bratu100% (2)

- Queens Orthopedic Inpatient Trauma PDFDokument27 SeitenQueens Orthopedic Inpatient Trauma PDFRema AmerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Report Supracondylar Fracture of Right FemurDokument37 SeitenCase Report Supracondylar Fracture of Right FemurSri Mahtufa Riski100% (1)

- Fracture of Radius and Ulna 3Dokument38 SeitenFracture of Radius and Ulna 3Noor Al Zahraa AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Distal Humeral Fractures-Current Concepts PDFDokument11 SeitenDistal Humeral Fractures-Current Concepts PDFRina AlvionitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transient SynovitisDokument9 SeitenTransient SynovitisMuhammad Taufik AdhyatmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuberculosis of Hip JointDokument25 SeitenTuberculosis of Hip JointYousra ShaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- All Papers Topic WiseDokument55 SeitenAll Papers Topic WiseZ TariqNoch keine Bewertungen

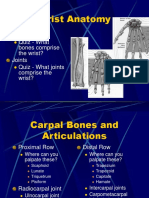

- Wrist Anatomy: Bones Quiz - What Bones Comprise The Wrist? Joints Quiz - What Joints Comprise The Wrist?Dokument63 SeitenWrist Anatomy: Bones Quiz - What Bones Comprise The Wrist? Joints Quiz - What Joints Comprise The Wrist?Mnn SaabNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scouting Hand & Whistle SignalsDokument2 SeitenScouting Hand & Whistle SignalsReine Chiara B. Concha94% (33)

- Jin Ce - Practical Chinese Qigong For Home HealingDokument243 SeitenJin Ce - Practical Chinese Qigong For Home HealingMomir Miric100% (5)

- BandagingDokument7 SeitenBandagingReggie San JoseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Current Practice of The Management of Little Finger Metacarpal Fractures... (2012)Dokument10 SeitenThe Current Practice of The Management of Little Finger Metacarpal Fractures... (2012)Anonymous LnWIBo1GNoch keine Bewertungen

- Splint Fabrication Evaluation FormDokument14 SeitenSplint Fabrication Evaluation FormJess QuickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Crush Injuries of The HandDokument26 SeitenCrush Injuries of The HandAbhishekNoch keine Bewertungen

- Broads: by Roxane GayDokument11 SeitenBroads: by Roxane GaymohammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Mudras For Emotional Healing - Forever ConsciousDokument4 Seiten8 Mudras For Emotional Healing - Forever ConsciousjayheshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kissing Lessons Practice Makes Perfect Book 1 Cassie Mint Full ChapterDokument55 SeitenKissing Lessons Practice Makes Perfect Book 1 Cassie Mint Full Chaptersteven.frerichs424100% (7)

- Surya NamaskarDokument30 SeitenSurya Namaskarcape_peter100% (4)

- Ernest Hutcheson - Elements of Piano Technique (1907)Dokument35 SeitenErnest Hutcheson - Elements of Piano Technique (1907)etrekan100% (2)

- 100 Top Sex Tips of All TimeDokument49 Seiten100 Top Sex Tips of All TimeliamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendicular Skeleton Quiz 1Dokument3 SeitenAppendicular Skeleton Quiz 1drincisor2Noch keine Bewertungen

- BDC Vol 1Dokument99 SeitenBDC Vol 1ayush.gNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 2: Basic Skills of VolleyballDokument8 SeitenUnit 2: Basic Skills of VolleyballHagiar NasserNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lapay BantigueDokument7 SeitenLapay BantiguePee Baradas83% (6)

- Ten Chi Jin Ryaku No MakiDokument41 SeitenTen Chi Jin Ryaku No MakiIan Adams100% (8)

- Target - Gipmer May 2017 Supplement T Arun BabuDokument7 SeitenTarget - Gipmer May 2017 Supplement T Arun BabuRohith MG100% (1)

- American Band College Sam Houston State University: Another ABC PresentationDokument50 SeitenAmerican Band College Sam Houston State University: Another ABC Presentationbottom2x100% (5)

- Ramp SafetyDokument63 SeitenRamp SafetyRacela SNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aplasia and Hypoplasia of The Radius Studies On 64 Cases and On Epiphyseal Transplantation in Rabbits With The Imitated DefectDokument154 SeitenAplasia and Hypoplasia of The Radius Studies On 64 Cases and On Epiphyseal Transplantation in Rabbits With The Imitated DefectJunji Miller FukuyamaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Guidelines For Input DeviceDokument30 SeitenGuidelines For Input Deviceapi-19807419Noch keine Bewertungen

- 6 X 9@uef@fDokument96 Seiten6 X 9@uef@fKofi VinceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Two Handed Process ChartDokument16 SeitenTwo Handed Process ChartraiyanirahilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Call SheetDokument32 SeitenCall SheetMichael Schearer100% (2)

- TWELVE-LINE TANTUI - Brennan TranslationDokument49 SeitenTWELVE-LINE TANTUI - Brennan TranslationpablozkumpuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Officiating BballDokument19 SeitenOfficiating Bballfor thierNoch keine Bewertungen

- AnthropometryDokument13 SeitenAnthropometryMustofa BahriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Jin Shin Jyutsu Finger MudrasDokument25 SeitenThe Jin Shin Jyutsu Finger Mudrasmarianaluca100% (7)

- The Neurological Exam: Mental Status ExaminationDokument13 SeitenThe Neurological Exam: Mental Status ExaminationShitaljit IromNoch keine Bewertungen