Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

12129311

Hochgeladen von

ayam bakar0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

30 Ansichten15 SeitenThis paper shares the Islamic perspective on business ethics, little known in the west. It also provides some knowledge of Islamic philosophy in order to help managers do business in Muslim cultures. The case of Egypt illustrates some divergence between Islamic philosophy and practice. The paper concludes with managerial implications and suggestions for further research.

Originalbeschreibung:

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis paper shares the Islamic perspective on business ethics, little known in the west. It also provides some knowledge of Islamic philosophy in order to help managers do business in Muslim cultures. The case of Egypt illustrates some divergence between Islamic philosophy and practice. The paper concludes with managerial implications and suggestions for further research.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

30 Ansichten15 Seiten12129311

Hochgeladen von

ayam bakarThis paper shares the Islamic perspective on business ethics, little known in the west. It also provides some knowledge of Islamic philosophy in order to help managers do business in Muslim cultures. The case of Egypt illustrates some divergence between Islamic philosophy and practice. The paper concludes with managerial implications and suggestions for further research.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 15

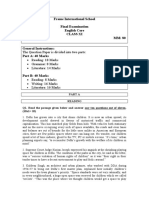

Islamic Ethics and the

ImpHcations for Business

Gillian Rice

ABSTRACT, As global business operations expand,

managers need more knowledge of foreign cultures,

in particular, information on the ethics of doing

business across borders. The purpose of this paper

is twofold: (1) to share the Islamic perspective

on business ethics, httle known in the west, which

may stimulate further thinking and debate on the

relationships between ethics and business, and (2)

to provide some knowledge of Islamic philosophy

in order to help managers do business in Muslim

cultures. The case of Egypt illustrates some divergence

between Islamic philosophy and practice in economic

life. The paper concludes with managerial implica-

tions and suggestions for further research.

KEYWORDS: business ethics, Egypt, Islamic business

ethics, Muslim culture

Introduction

Over the centuries, as state and church separated,

particularly in western societies, religion became

a private matter. The so-called "value-free

society" developed and economists focused

exclusively on the mechanics of economics.

There is a growing realization that value-free

economics is a misnomer. Post-modern thinkers

Gillian Rice is Associate Professor of Marketing at

Thunderhird, The American Graduate School of Inter-

national Management. Her research includes study of

economic development, environmental concerns and

marketing practices in developing countries. She is a

founding member of the International Management

Development Association. Her publications include

articles in International Marketing Review,

International Journal of Forecasting, Information

and Management, The International Executive and

Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

have advocated changes over the past few decades

and there has been a reintroduction of a moral

dimension in business.

An important task for many managers is how

to integrate this moral dimension into business

conducted across borders. Managers need an

appreciation of the ethical norms of different

groups and cultures in order to gain complete

understanding of the cultural environment in

which the firm must operate (Al-Khatib et al.,

1995). Relatively few empirical studies have

addressed culturally-related ethical issues (see for

example, Becker and Fritzsche, 1987; Akaah,

1990; Vitell et al., 1993; Nyaw and Ng, 1994).

Based upon the results of a study that found some

surprising significant differences between the

values of American and Thai marketers,

Singhapakdi et al. (1995) suggest that multina-

tional corporations should train their marketing

professionals differently in different parts of the

world. Amine (1996) goes further and urges that

the role of global managers should be one of

"moral champions," committed to pursuing the

best in ethical and moral decision-making and

behavior. The definition of "best" is not an easy

task, however, when one takes into account the

many different moral philosophies that exist.

In recent years there have been a number of

articles pubhshed in the Journal of Business Ethics

which have discussed the positions of various

faiths regarding the relevance of religious ethical

principles to business decision-making (see for

example, Williams, 1993; Green, 1993; Rossauw,

1994; Gould, 1995). The Pope's Centesimus

Annus argues that what is lacking in our time is

a moral culture capable of transforming

economic life so that it has a context in a

humane community (Williams, 1993).

Journal of Business Ethics 18: 345- 358, 1999,

1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands.

346 Gillian Rice

My focus in this paper is on the ethical

principles which relate to business and which are

contained in the religion of Islam. Islam is gen-

erally misunderstood and it is often surprising

to some that it contains an entire socio-economic

system. In Islam, it is ethics that dominates eco-

nomics and not the other way around (Naqvi,

1981). My purpose is twofold: (1) to share a per-

spective on business ethics, little known in the

west, which may stimulate further thinking and

debate on the relationships between ethics and

business, and (2) to provide some knowledge of

Islamic philosophy in order to help managers

doing business in Muslim cultures deal with

cultural differences. The paper is organized as

follows. First is a description of the Islamic

ethical system. Next is a discussion of the dif-

ferences between philosophy and practice in

Islamic business ethics. This discussion forms the

basis for guidelines on doing business with people

in Muslim cultures. Egypt is used as an illustra-

tive case.

The Islamic ethical system

Muslims derive their ethical system from the

teachings of the Qur'an (which Muslims believe

is a book revealed by God to Muhammad

in seventh century Arabia), and from the

sunnah (the recorded sayings and behavior of

Muhammad). The goals of Islam are not pri-

marily materialist. They are based on Islamic

concepts of human well being and good life

which stress brotherhood/sisterhood and socio-

economic justice and require a balanced satisfac-

tion of both the material and spiritual needs of

all humans (Chapra, 1992).

A "moral filter"

There exists in most societies a relative scarcity

of resources with unlimited claims upon them. A

free-market capitalist economy uses market-

determined prices as a filtering mechanism to

distribute resources. The use of the price system

alone, however, can frustrate the realization of

socio-economic goals. Under a system of state

control, the allocation of resources is in the hands

of a bureaucracy, which is cumbersome and inef-

ficient. According to Chapra (1992), the Islamic

worldview implies that the market system should

be maintained, but that the price mechanism be

complemented with a device that minimizes

unnecessary claims on resources. This device is

the "moral filter." This means that people would

pass their potential claims on resources through

the "filter of Islamic values" so that many claims

would be eliminated before being expressed in

the marketplace. Resources would not be allowed

to be diverted to the production of luxuries until

the production of necessities was ensured in suf-

ficient quantities (Siddiqi, 1981). The definition

of luxurious or extravagant is related to the

average standards of consumption in a society, the

idea being that large departure from the standards

would not be permissible.

Keynes' (1972) observations on this subject

may be useful. He stated that even though "the

needs of human beings may seem to be insa-

tiable," . . . "they fall into two classes - those

needs which are absolute in the sense that we feel

them whatever the situation of our fellow human

beings may be, and those which are relative ones

in the sense that their satisfaction lifts us above

or makes us feel superior to others. Needs of the

second class, which satisfy the desire for superi-

ority, may indeed be insatiable; for the higher the

general level, the higher still are they. But this is

not so true of the absolute needs." Islamic jurists'

categories of necessities {daruriyyat), conveniences

(hayiyyat) and refinements (tahsiniyyat) would fall

into Keynes' first class of needs. These are any

goods and services which fulfill a need or reduce

a hardship and make a real difference in human

well-being. Thus "comforts" are included here

(Chapra, 1992). Luxuries (the second class of

needs), however, are goods and services derived

for their snob appeal and make no difference to

a person's well-being. Galbraith (1958) refers to

this second class of needs as "wants."

Consumer advocates in the U.S. have long

been critical of business practices that increase

the desire for "wants" and subsequently have

adverse cultural and social effects (Williams,

1993). For example, in pursuit of profit maxi-

mization, businesses often subject the consumer

Islamic Ethics

347

to advertising and sales promotion campaigns that

appeal to the consumer's vanity, sex appetite and

envy, either overtly or covertly. Consumers are

encouraged to beheve that their actualization and

social esteem are dependent on the frequency and

value of their purchases. This leads in turn to a

tremendous amount of wasteful production,

with adverse environmental as well as social

implications. According to the United Nations

Development Program (UNDP) Human Devel-

opment Report (1994), the lifestyles of the rich

nations must change; the north has a fifth of the

world's population and four-fifths of its income

and it consumes seventy percent of the world's

energy, seventy-five percent of its metals and

eighty-five percent of its wood. Even in these

rich countries, some of the essential needs of the

poor remain unfulfilled, and high pollution and

rapid depletion of non-renewable resources

occur.

The question, of course, is how to implement

the "moral filter" without coercion or despotism.

The filter mechanism of values must be socially-

agreed upon and some way has to be devised to

motivate consumers and businesspeople to abide

by these values. From an Islamic point of view,

social change must be gradual and cannot be

achieved through force. The Qur'anic injunction

"There is no compulsion in religion" (Qur'an

2:256) is relevant here. Change can occur by

inviting people to alter their ways or by setting

an example. Historically this is how Islam rapidly

spread through a large part of the world in the

seventh and eighth centuries (Eaton, 1994). For

example, when Muslim merchants traveled to

distant lands, the inhabitants of those lands were

impressed by the traders' social and business

conduct and so became curious about their

beliefs. Many of these inhabitants subsequently

became Muslims. A parallel exists today with

respect to the "green" movement which con-

tinues to spread around the globe. The adoption

of environmentally conscious behavior is occur-

ring through example, encouragement and edu-

cation, as well as by legislation. Indeed, in the

environmental context, legislation is insufficient.

Only when the political will and support of the

populace are strong enough, are environmental

laws adequately enforced.

The Islamic ethical system contains specific

guidehnes for achieving the moral filter and for

conducting business. These guidelines derive

from the interrelated concepts of unity, justice

and trusteeship which I explain below.

Unity (tawhid)

The key to the business philosophy of Islam lies

in a person's relationship with God, His universe

and His people. In common with other revealed

religions is the moral appeal to humans to sur-

render themselves to the will of God. Islam goes

beyond this exhortation and teaches that all life

is essentially a unity because it also provides the

practical way to pattern all facets of human hfe

in accordance with God's will. There should be

unity of ideas and actions in a person's existence

and consciousness (Asad, 1993). Muslims believe

that because people are accountable to God, and

their success in the hereafter depends on their

performance in this life on earth, this adds a new

dimension to the valuation of things and deeds

in this life (Siddiqi, 1981). Islam is simply a

program of life in accord with the "laws of

nature" decreed by God. A definite relationship

between fellow humans is thus prescribed. This

is the relationship of brotherhood or sisterhood

and equality (Abu-Sulayman, 1976). In this sense,

unity is a coin with two faces: one implies

that God is the sole creator of the universe and

the other implies that people are equal partners

or that each person is a brother or sister to the

other. As far as business is concerned, this

means cooperation and equality of effort and

opportunity.

Justice (adalah)

Islam is absolutely unambiguous in its objective

of eradicating from society all traces of inequity,

injustice, exploitation and oppression. The

Qur' an also condemns vicarious guilt or merit

and teaches the greatest possible individualism

" . . . no bearer of burdens can bear the burdens

of another; , . . man can have nothing but what

he strives for . . ." (Qur'an 53:38-9). This indi-

348 Gillian Rice

vidualistic outlook on the spiritual destiny of

humanity is counterbalanced by a rigorous con-

ception of society and social collaboration. In

their acquisition of wealth, however, people

should not lie or cheat; they must uphold

promises and fulfill contracts. Usurious dealings

are prohibited. Islam teaches that all wealth

should be productive and people may not stop

the circulation of wealth after they have acquired

it, nor reduce the momentum of circulation

(Chapra, 1992).

The intense commitment of Islam to justice

and brotherhood demands that Muslim society

take care of the basic needs of the poor.

Individuals are obliged to earn a living and only

when this is impossible does the state intervene.

The Islamic institution o zakah, that is, a wealth

tax comprising compulsory charitable-giving for

specially designated groups in society, facilitates

the care of all members of society. The rich are

not the real owners of their wealth; they are only

trustees. They must spend it in accordance with

the terms of the trust, one of the most impor-

tant of which is fulfilling the needs of the poor.

The word "zakah" means purification and as

such, income redistribution is not only an

economic necessity but also a means to spiritual

salvation (". . . of their wealth take alms so that

you might purify and sanctify." Qur'an 9:103).

Thus, economics is effectively integrated with

ethics (Naqvi, 1981).

Trusteeship (khilafah)

People are viewed as trustees of the earth on

behalf of God. This does not mean a negation

of private property but does have some impor-

tant implications. No inhibitions attach to

economic enterprise and people are encouraged

to avail themselves of all opportunities available.

There is no conflict between the moral and

socio-economic requirements of life. There is a

very wide margin in a person's personal and

social existence. People may be ascetics or, after

paying the wealth tax, may enjoy fully their

remaining wealth. Yet, resources are for the

benefit of all and not just a few and everyone

must acquire resources rightfully. Although

material prosperity is desirable, it is not a goal

in itself. What is crucial is the motivation, the

"ends" of economic activity. Given the right

motivation, all economic activity assumes the

character of worship (Siddiqi, 1982). Indulgence

in luxurious living and the desire to show-off is

condemned. Islam does not tolerate conspicuous

consumption (Chapra, 1992).

Resources must also be disposed of in such a

way as to protect everyone's well-being (Al-

Faruqi, 1976). No one is authorized to destroy

or waste God-given resources. This is very

relevant to ethics concerning business and the

environment: when Abu Bakr, the first ruler of

the Islamic state after Muhammad, sent someone

on a war assignment, he exhorted him not to

kill indiscriminately or to destroy vegetation or

animal life, even in war and on enemy territory.

Thus there was no question of this being allowed

in peacetime or on home territory. Trusteeship

is akin to the concept of sustainable development.

Models of sustainable development do not regard

natural resources as a free good, to be plundered

at the free will of any nation, any generation or

any individual (UNDP, 1994). The notion of

trusteeship is also common to the Jewish and

Christian faiths; Green (1993) refers to Psalms

24:1, "The earth is the Lord's and the fullness

thereof."

The need for balance

Muhammad advised Muslims to be moderate in

all their affairs; he described Islam as the "middle

way." A balance in human endeavors is neces-

sary to ensure social well-being and continued

development of human potential. Chapra (1992)

notes that Islam recognizes what Marxism sought

to deny: the contribution of individual self-

interest through profit and private property to

individual initiative, drive, efficiency and enter-

prise. At the same time, Islam condemns the evils

of greed, unscrupulousness and disregard for the

rights and needs of others, which the secularist,

short-term, this-worldly perspective of capitalism

sometimes encourages. The individual profit

motive is not the chief propelling force in Islam

(Siddiqi, 1981). Social good should guide entre-

Islamic Ethics 349

preneurs in their decisions, besides profit. A

relevant saying of Muhammad is "work for your

worldly life as if you were going to live forever,

but work for the life to come as if you were

going to die tomorrow."

Islam, like some other religions, places a

greater emphasis on duties than on rights. The

wisdom behind this is that if duties (relating to

justice and trusteeship, for example) are fulfilled

by everyone, then self-interest is automatically

held within bounds and the rights of all are

undoubtedly safeguarded. Society is the primary

institution in Islam, not the state (Cantori and

Lowrie, 1992). Chapra (1992) argues that in

order to create an equilibrium between scarce

resources and the claims on them in a way that

realizes both efficiency and equity, it is neces-

sary to focus on human beings themselves, rather

than on the market or the state. As emphasized

by Cantori and Lowrie (1992), the Islamic jurists

and the Islamic law or "shari'ah" (literally,

"road") limit governmental power. The shari'ah

is so all encompassing that there is less need for

legislation regarding issues of ethics, social

responsibility and human interaction. In partic-

ular, Muslims believe that the Qur' an contains a

final and unambiguous statement of the truth,

added to what had gone before (for example, the

messages delivered to Moses and Jesus). The duty

of the Muslim community is to preserve this

message. Thus, Muslims have a profound horror

of anything regarded as innovation in matters of

religion, including what modern Christians

interpret as necessary adaptations of religion to

changing times (Eaton, 1994).

The emphasis is therefore on the human being

rather than on state power. The real wealth of

societies is with their people. An excessive obses-

sion with the creation of material wealth can

obscure the ultimate objective of enriching

human lives. Humans are thus the ends as well

as the means. Unless humans are motivated to

pursue their self-interest within the constraints of

economic well-being (the application of the

"moral filter"), neither the "invisible hand" of

the market nor the "visible hand" of central

planning can succeed in achieving socio-

economic goals (Chapra, 1992).

Summary

It should be emphasized that in Islam, business

activity is considered to be a socially useful

function; Muhammad was involved in trading for

much of his life. Great importance is attached to

views relating to consumption, ownership, goals

of a business enterprise and the code of conduct

of various business agents. A summary of the

key ethical principles in Islam which relate to

business practices is presented in Table I. Because

Judaism, Christianity and Islam are closely

related, many ethical principles such as honesty,

trustworthiness and taking care of the less

fortunate, are universal among the three religions,

and indeed, among most moral codes. For

example, as pointed out by Rossauw (1994),

someone with a Christian understanding of the

unconditional value of life cannot be careless in

the workplace about product and quality stan-

dards that pose a threat to the lives of consumers

or employees. However, Rossauw suggests that it

is not the role of the church to approve or

condemn economic systems. As economic

systems are morally ambiguous, he encourages

Christians to "keep a critical distance from the

economic system in which they are working."

In contrast, because Islam supplies a practical

life-program, it is important to note that the

Islamic socio-economic system includes detailed

coverage of specific economic variables such as

interest, taxation, circulation of wealth, fair

trading, and consumption. Islamic law (shari'ah)

derived from the Qur' an and sunnah also

covers business relationships between buyers

and sellers, employers and employees and lenders

and borrowers (for full details, see for example,

Keller, 1994). Note that there is no difference

between Muslims and non-Muslims in legal

rulings concerning commercial dealings. For

example, it is unlawful to undercut another's

price (whether that person be Muslim or non-

Muslim) during a stipulated option to cancel

period. A seller is not permitted to tell the

buyer "cancel the deal and I'll sell you one

cheaper." Also, whoever knows of a defect in an

article he/she is selling is obliged to disclose it,

to any buyer, Muslim or non-Muslim. Both

Islamic and non-Islamic employees must be

350 Gillian Rice

TABLE I

Examples of ethical principles in Islam relating to business practices

Ethical principle Relevant business practice(s)

Unity

"No Arab has superiority over any non-Arab and no non-

Arab has any superiority over an Arab; no dark person has

superiority over a white person and no white person has any

superiority over a dark person. The criterion of honor in the

sight of God is righteousness and honest living." Saying of

Muhammad (Sallam and Hanafy, 1988).

"O mankind! We created from you from a single (pair) of a

male and a female, and made you into nations and tribes,

that you may know each other . . ." (Qur'an 49:13).

" . . . man can have nothing but what he strives for . . ."

(Qur'an 53:39).

"God likes that when someone does anything, it must be

done perfectly well." Saying of Muhammad (Sallam and

Hanafy, 1988).

" . . . say, ' O my Lord! increase me in knowledge.' "

(Qur'an 20:114).

"The acquisition of knowledge is a duty incumbent on every

Muslim, male and female." Saying of Muhammad (Sallam and

Hanafy, 1988).

Trusteeship

"God does command you to render back your trusts to those

to whom they are due . . ." (Qur'an 4:58)

" . . . wear your beautiful apparel at every time and place of

prayer: eat and drink: but waste not by excess . . ."

(Qur'an 7:31).

" . . . to God belongs all that is in the heavens and on

earth . . ." (Qur'an 3:129).

fustice

" . . . God loves not the arrogant, the vainglorious (nor) those

who are niggardly, enjoin niggardliness on others . . ."

(Qur'an 4:36-7).

" . . . and spend of your substance in the cause of God, and

make not your own hands contribute to your destruction;

but do good . . ." (Qur'an 2:195).

Equal opportunity and non-discriminatory

behavior in hiring, buying and selling.

Teamwork. International business.

Rewards should be received only after

expending efforts.

Excellence and quality of work.

Importance of knowledge-seeking, research

and development, scientific activity,

training programs, executive training,

technology transfer.

Fulfilling obligations and trust in business

relationsbips and tbe workplace.

It is acceptable to have wealth and to

consume but not to waste resources.

Gare for the environment.

There is no unlimited right to private

property.

Prohibition of boarding. Encouragement of

spending, investment in business enterprise

and circulation of wealth.

Condemnation of ostentatious consumption.

Islamic Ethics 351

Table I (continued)

Ethical principle Relevant business practice(s)

Justice continued, . . ,

". , . wealth and children are allurements of the life of this

world , . ," (Qur'an 18:46),

", . , He has raised you in ranks, some above others: that He

may try you in the gifts that He has given you" (Qur'an 6:t65),

", . . it is We (God) who portion out between them their

livelihood in the life of this world: and We raise some of

them in ranks so that some may command work of others.

But the Mercy of your Lord is better than the (wealth)

which they amass," (Qur'an 43:32),

". , . of their wealth take alms, so that you might purify and

sanctify , , ," (Qur'an 9:103),

"God permits trade but forbids usurious gain*,"

(Qur'an 2:275),

", , , give just measure and weight, nor withhold from the

people the things that are their due , , ," (Qur'an 11:85),

"He who cheats is not one of us," Saying of Muhammad

(Keller, 1994).

", . , don't outbid one another in order to raise the price,

, , , don't enter into a transaction when others have already

entered into that transaction and be as brothers one to

another," Saying of Muhammad (Hanafy and Sallam, 1988),

Acquisition of wealth is given reduced

consideration in the scale of human values.

Income inequality is permitted.

Distinction between managers, workers,

professionals, etc, is acceptable.

Income redistribution: wealth should be

shared with those less fortunate.

Unlawfulness of loans by which lender

obtains benefit.

Give full measure and weight.

Whoever knows of a defect in something is

obliged to disclose it.

Fairness in contract negotiation.

", , , make your utterance straightforward , , ," (Qur'an 33:70), Truthfulness and directness in negotiation,

"Qn the day of judgment, the honest Muslim merchant

will stand side by side with the martyrs," Saying of

Muhammad (Ali, 1992),

", , , stand out firmly for justice, as witnesses to God, even

against yourselves, or your parents, or your kin, and whether

it be (against) rich and poor,"

Non-discriminatory workplace practices.

Protection for "whistle-blowers." No

special privileges for those with wealth or

status.

", . . nor shall We (God) deprive them (of the fruit) of aught Importance of individual responsibility,

of their works: (yet) is each individual in pledge for his deeds,"

(Qur'an 52:21),

In the Qur'an, the Arabic word used is "riba" which lexically means "increment" (Keller, 1994),

352 Gillian Rice

treated v^ith the same just, equitable and honest

approach.

Note that Islam is not an ascetic religion. Islam

allows people to satisfy all their needs and to go

beyond. The objective should not be to create

a monotonous uniformity in Muslim society.

Simplicity in consumption can be attained in

lifestyles alongside creativity and diversity.

Neither does Islam mean an absence of economic

liberalization. There is a different kind of liber-

alization: one in v^^hich all private and public

sector economic decisions are first passed

through the filter of moral values before they are

made subject to the discipline of the market.

Undoubtedly, to implement the "moral filter"

in practice requires the dedication of a large

number of market participants. There is there-

fore frequently a wide gap between the philos-

ophy and practice of Islamic ethics in countries

with predominantly Muslim populations. The

next section examines this issue with reference

to Egypt.

Philosophy and practice: the example of

Egypt

The reality of present-day Muslim life is far from

the ideal possibilities given in the religious teach-

ings of Islam (Asad, 1993). Because of a number

of historical factors, the dominant ideology in

Muslim countries is not Islam but rather secu-

larism along with a mixture of feudalism, capi-

tahsm and socialism (Chapra, 1992). Islam is

conspicuous by its absence, particularly in the

political and economic fields. In the Mushm

countries, unjust and oppressive political and

socio-economic systems have been the cause of

the Islamic resurgence. The socio-economic

restructuring that Islam represents threatens the

governments' short-term (but not necessarily

long-term) interests.

Impact of economic liberalization

For one dimension of life such as business, it is

difficult to differentiate between the impact of

the religious context of the behavior and the total

cultural system (Moore and Delener, 1986).

Egyptians are a religious people closely attached

to their religious culture and identity. There is a

growing awareness among them that many

Islamic cultural traits are being superseded by

western values, institutions and practices (Najjar,

1992; Asad, 1993). Joy and Ross (1989) observe

how, today, societal success in the third world is

measured and evaluated in terms of proximity

to the institutions and values of the west.

Nevertheless, new techniques, ideas and values

will be accepted only if they meet the real needs

of people more effectively than existing ones.

Had such institutions such as liberal democracy,

capitalism or socialism succeeded in solving the

pressing problems of Egyptian society, they

probably would not have generated such hostility

(Najjar, 1992). Instead, they have been seen as

the cause of rapid deterioration ofthe quality of

Islamic life and the decline ofthe Muslim world.

The emphasis on conspicuous consumption and

changes in lifestyles which followed Sadat's

"infttah" (open-door) economic policy and move

to a free market economy in the seventies and

eighties aggravated inflation and unemployment

in Egypt, sharpened social disparities and

enlarged the class of dispossessed and disaffected.

The economic liberalization policy concentrated

on trade, the importance of consumer items and

expansion of services such as tourism and hotel

management (Tuma, 1988), rather than on indus-

trial projects. Privatization efforts continue,

although rather slowly because of the govern-

ment's philosophy of control. A "new class" has

arisen as a result of the open-door policy.

Although it is relatively small, it accumulated

much economic and political power during the

eighties (Jabber, 1986). This class consists mainly

of entrepreneurs, professional and high salaried

employees of the private economy.

Cultural dualism

The artificial symbiosis of Islamic ethical beliefs

and "alien" socio-economic philosophies and

systems has led to the emergence of bifurcated

societies promoting schizophrenic behavior both

at the individual and collective level (Naqvi,

Islamic Ethics 353

1981). Ali (1992) discusses the Arab dual identity

in detail, attributing it to two main factors: (1)

colonialism which instilled feelings of inferiority

in Arab thought and (2) the artificial division of

lands into nation-states. The influx of multina-

tional corporations into the region also con-

tributed to cultural and social alienation. Because

of social and political instability in countries like

Egypt, people tend to believe everything in life

is temporary and they make their way on doubt.

Previous studies (for example, Rawwas et al.,

1994; Al-Khatib et al., 1994) suggest that social

and political instability or economic hardship

may cause tense, pessimistic and struggling indi-

viduals to sacrifice ethicality for basic survival

needs. In particular, Tuma (1988) identifies

three main features of Egyptian culture which

Egyptians have internalized in their behavior to

enable them to deal with the difficulties of life

in Egyptian society. These three features are inde-

cision, procrastination and indifference. People

will not firmly answer yes or no to a request,

but will say "insha'Allah (God willing). They will

not do today what they can do tomorrow, but

will say "bukra" (tomorrow), as if time had no

cost. They accept indecision and procrastination

and their effects with apparent indifference, and

say "ma'alesh" (it doesn't matter), even though

the costs may be substantial.

If God's name is invoked in every situation and

if every action depends on the will of a higher

authority, Tuma (1988) asks, what role does the

individual play? What responsibility must he or

she carry? It is important to note that Muslims

are exhorted in the Qur'an never to say that they

will do something the next day without also

saying "insha'Allah!' This does not absolve the

individual of responsibility; people should make

strong effort and work hard to achieve their

business plans. If these go awry, in hindsight, a

Muslim would consider this to be the will of

God. This may be viewed as "predestination in

reverse." Yet there is no concept of predestina-

tion in terms of the future as humans have free

will and must make their own conscious life (and

business) decisions. As Eaton (1994) explains, the

concept of the divine omniscience would be

empty if humans did not acknowledge that God

knows not only all that has ever happened but

also all that will ever happen, and that "the

'future' is therefore in a certain sense, already

'past.' " In the words of the Bible, "That which

hath been 15 now; and that which is to be hath

already been" (Ecclesiastes, 3:15). Since humans

are subject to time and cannot see the future,

they have an experience of free choice. They

make their choices and act accordingly; only

when the act is past can they say "it was written"

or "it was decreed for us from the beginning of

time" (Eaton, 1994). The Qur' an states that a

person achieves only that for which he makes an

effort: " . . . And that man can have nothing but

what he does (good or bad) . . ." (Qur'an 53:39).

With respect to "insha'Allah" there appears

to be a tension between the Qur'an's teaching

and what sometimes occurs in practice. Tuma

(1988) suggests that, in practice, the deference to

a higher authority may be understood to mean

"if the boss wills it." If no-one will make deci-

sions, then no-one will bear responsibility.

Individual initiative is therefore reduced, as all

decisions are centralized, as a way of avoiding

responsibility and blame. Based on this author's

experiences in Egyptian society, the term

"insha'Allah" is also often used as a way of

meaning "no" without actually saying "no." It is

difficult to obtain firm commitment from

business partners and to plan accordingly.

Al-Khatib et al. (1995) provide the following

explanation for this type of behavior: one ethical

standard is used to handle daily decisions while

the other, influenced by religious teachings, is

not implementable because of the economic

hardship faced by the people.

Informality in business relationships

Social relations, the traditional extended family

structure and nepotism have a strong influence

on business behavior. Egyptians prefer to do

business with people they know and like and

who they consider as friends. They are extremely

hospitable and generous and exchange gifts often.

As business relationships are often with friends or

family, these relationships are characterized by

informality which is subsequently reflected in the

treatment of time, weights and measures, and

354

Gillian Rice

quality control of goods and services (Tuma,

1988). Table I includes several Islamic ethical

principles which counter this informality. For

example, there should be no discrimination

between human beings, whether they are family

members or not, full measure and full weight

should always be given to buyers, along with

explanation of any deficiencies in products to be

sold, and hard work and excellence or quality in

work is urged.

Implications for doing business with people

in Muslim cultures: the case of Egypt

The bifurcated nature of the Egyptian culture

creates some interesting problems for foreign

executives doing business in Egypt. On the one

hand, it might be useful for a foreign executive

to understand and show appreciation for the

Islamic concepts of unity (unity of faith and

action, equality of humans), trusteeship and

justice. On the other hand, managers must

consider the difficult realities of everyday living

which lead people to forgo the ethical princi-

ples of the Islamic tradition.

Can managers of multinationals play the role

of "moral champions" as Amine (1996) suggests?

About sixty percent of multinationals have codes

of ethics in place {The Economist, 1995). Many

managers ignore ethical diversity, however, and

implement the same code of ethics around the

world. Vasquez-Parraga and Kara (1995) argue

that codes of ethics have not worked. Some

contend that ethics cannot be taught to managers

because their values are already formed. There

are, however, numerous documented cases that

show ethics can be influenced by organizational

pressures (Smith and Quelch, 1992). Rogers et

al. (1995) state that, especially in developing

countries like Egypt, managers should develop

and implement a balanced business philosophy

which integrates the profitability requirements of

multinationals with the social, economic and

ecological needs of developing countries and

those who live in them.

For example, the U.K.-based retail outlet

"Egyptian House" is a joint venture with Egypt's

Foundation for the Productive Families, a gov-

ernment-funded cooperative set up to make

needy Egyptian families self-sufficient (Thomas,

1996a), A non-profit U,S.-based cooperative,

"Women's Organization Middle East Network"

(WOMEN), unites women from Egypt, Israel,

Jordan and Palestine. Its goals include training

women in management, technology, finance and

marketing techniques, as well as promoting social

services. Products are to be marketed regionally

and internationally, with the ultimate aim of

developing a franchise system (Thomas, 1995).

Niclas, a German clothing retailer is opening a

large number of outlets in the Middle East, with

plans to locate production as well as retail outlets

in Egypt. It can be argued that Niclas is pro-

moting fashion and "luxurious" clothing items.

Nevertheless, the company's plans to promote

brand loyalty also include starting a children's

club led by eco-friendly character "Niclas" who

will give talks about nature and ecology. Niclas

has a regional partner to assure regional adapta-

tion of business approaches (Thomas, 1996b).

There is undoubtedly a need for genuine

understanding of the ethics of foreigners with

whom an international manager seeks to do

business, whether these are other businesspeople,

consumers or government representatives. In

each particular culture, this understanding should

extend to people's aspirational ethics as well as to

their everyday practices. Managers should not

look merely at the practices of the most corrupt

level of society (Tuma, 1988; Al-Khatib et al.,

1995).

The foregoing discussion of Islamic philosophy

and practice in Egypt suggests a number of impli-

cations for international executives. These are

detailed in Table II. The Egyptian culture, based

in the Islamic tradition, focuses on social issues

such as family, health and training for young

people. Marketing and public relations efforts

must therefore emphasize these issues (Wilkinson,

1996). For example, Egyptian House is planning

to sponsor Egyptian students on annual place-

ments to learn marketing techniques. In the tele-

phone switching market, European firms have

strengthened their position in Egypt by visiting

agents more frequently and educating their agents

regarding new technology. Such efforts have led

to closer, more successful business relationships

Islamic Ethics

355

TABLE II

Illustrations of the business implications of Islamic philosophy and practice in Egypt

Islamic philosophy Egyptian practice Implications for the foreign executive

Unity

Non-discrimination in the

workplace

Importance of knowledge-seeking

Trusteeship

Care of the environment

Use of wealth for social causes,

to aid less fortunate people.

Justice

Precision in business dealings,

honesty, fuU information to the

buyer, etc. Individual

responsibility.

Prohibition of usurious

transactions e,g. payment and

receipt of interest.

Nepotism, importance of social

relationships in business

Egyptians place great emphasis on

education, wherever possible,

given the country's level of

economic development.

Egyptians have neglected this, in

part because of more pressing

economic problems, but also

because of attitude. Changes are

occurring. Environmental laws

being implemented.

The "new" class which benefited

from liberalization tends to engage

in conspicuous consumption.

Yet, there are also efforts on

the part of some Islamists to

develop social welfare programs.

Informality in treatment of time,

weights and measures, business

on a "handshake," Indecision,

procrastination. Lack of trust.

Efforts to gain benefits from the

state.

Some Egyptian businesspeople

observe this ruling; others do

not.

Trust and friendship must be

developed, often slowly, before

business is possible. Hiring of

family members/friends by

Egyptian partner may result in

less than qualified individuals

for certain positions.

Provide training as part of contracts;

technology transfer; visits to foreign

company's home facilities much

appreciated.

Business opportunities in

environmental technology field.

Marketing appeals could be made

using the Islamic perspective on the

environment.

International managers have the

opportunity to be "moral

champions," E,g, success of Egyptian

House in UK, a joint venture with

Egypt's Foundation for the

Productive Families (Thomas,

1996a), Also, possibilities for

cause-related marketing in Egypt.

Foreign executives need to be

extremely patient and cautious.

Showing strong commitment,

however, will likely increase the

commitment of the Egyptian

partner. Need for local agent/

partner.

Need to find out the views of the

Egyptian partner. Foreign executives

would be wise to avoid expressing

opinions, but should follow desires of

Egyptian partner. Opportunity for

innovative financing methods, Islamic

financing institutions and instruments

growing worldwide with many major

western banks involved.

356

Gillian Rice

{Middle East Executive Reports, 1995). Innovative

financing methods based on Islamic practice are

growing worldwide and are accessible to western

business executives. For example. Citibank's

Islamic investment bank is headquartered in

Bahrain. The Islamic Development Bank has an

export credit agency. The Islamic Corporation

for the Insurance of Investment and Export

Credit {Middle East Economic Digest, 1995).

While there are some differences between phi-

losophy and practice, it should be remembered

that the Islamic worldview has an enduring and

strong influence on Egyptian culture. In common

with most peoples of the world, Egyptians are

very favorably impressed and honored by a for-

eigner's genuine desire to learn about the ideal

to which they aspire. An understanding of

Egyptians' inner conflicts in business ethics will

be appreciated. At all times, foreign executives

should demonstrate respect for Islam and they

will find that, in turn, the Egyptians will truly

respect the foreigners' religious behefs and ethical

ideals.

Conclusion

In response to the need for further research and

discussion about business ethics in different

cultures, I have described Islamic philosophy

regarding business practices. It is important not

merely to understand the philosophy or ideal,

however. Knowledge of ethics in practice is vital

to the international manager. The illustration of

Egypt shows considerable diversities between

philosophy and practice; diversities which if

understood, can provide a foreign executive with

ideas on how to negotiate with Egyptians and

even what kinds of products or services might

be appreciated. The specific Egyptian case, of

course, has limited generahzabihty, as all cultures

have unique traits. Nevertheless, the analytical

framework I use is applicable in any culture.

Managers should examine first a culture's ideal

set of ethics, and second, the actual ethical

practice. They should also attempt to investigate

reasons for differences between these two.

Future empirical research could focus on what

are the ethical issues of most concern to Muslim

managers and how these managers deal with

issues of social responsibility in their countries.

The results would be salient in the development

and implementation of multinational companies'

codes of ethics. In addition, organizations seeking

to be "good corporate citizens" in Muslim coun-

tries could benefit from this kind of research.

Because much international business is conducted

using agents and various types of joint ventures,

it is important to understand the ethical ideals

and practices of Muslim business partners. Also,

how do they resolve conflicts with non-Muslim

partners? Research should include comparisons

of different Muslim countries, such as those from

North Africa, the Gulf region, and Southeast

Asia. Furthermore, what is the impact of Islamic

thinking on different business functions such as

finance and marketing? For example, what kind

of advertising is not only acceptable in Islamic

cultures, but is preferred and more effective? The

most appropriate way to research these issues is

by conducting surveys to ascertain the attitudes

and practices of managers and consumers in

Muslim countries. In some contexts, such as

advertising research, laboratory and field exper-

iments may also be feasible.

The Islamic ideal is part of a universal Islamic

culture, common to all Muslims around the

world. Hence, a deeper appreciation of Islam

can be advantageous to executives conducting

business with any Muslims, from Indonesia to

Morocco, and from the former Soviet Central

Asian repubhcs to South Africa.

References

Abu-Sulayman, A, A,: 1976, ' The Economics of

Tawhid and Brotherhood', Contemporary Aspects

of Economic Thinking in Islam (American Trust

Publications, Indianapolis, IN),

Akaah, I, P: 1990, 'Attitudes of Marketing

Professionals toward Ethics in Marketing Research:

A Cross-National Comparison', Jowma/ of Business

Ethics 9, 49-53,

Ali, A. J.: 1992, ' The Islamic Work Ethic in

Arabia', paper presented at the World Business

Congress, April 9- t 2 (Available from A, J. Ali,

Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, PA

15705),

Islamic Ethics

357

Amine, L, S.: 1996 (forthcoming), ' The Need for

Moral Champions in Marketing', European Journal

of Marketing 30,

Asad, M,: 1993, Islam at the Crossroads (Dar al-Andalus

Ltd., Gibraltar).

Al-Khatib, J. A., S. Vitell and M. Rawwas: 1994,

'Consumer Ethics: A Cross Cultural Investigation',

in S, T, Cavusgil (eds.). Advances in International

Marketing (JAI Press),

Al-Khatib, J, A,, K, Dobie and S, J, Vitell: 1995,

'Consumer Ethics in Developing Countries: An

Empirical Investigation', 4, 87-109,

Al-Faruqi, I, R. A.: 1976, 'Foreword', Contemporary

Aspects of Economic Thinking in Islam (American

Trust Publications, Indianapolis, IN),

Becker, H. and D, J. Fritzsche: 1987, 'A Comparison

of the Ethical Behavior of American, French and

German Managers', Columbia Journal of World

Business, 87-95,

Cantori, L, J, and A, Lowrie: 1992, 'Islam,

Democracy, The State and The West', Middle East

Policy 1, 49-61.

Chapra, M. U: 1992, Islam and the Economic Challenge

(International Institute of Islamic Thought,

Herndon, VA),

Eaton, G.: 1994, Islam and The Destiny of Man (The

Islamic Texts Society, Cambridge),

Galbraith, J, K.: 1958, The Affluent Society (Houghton

Mifflin, Boston, MA).

Gould, S, J.: 1995, ' The Buddhist Perspective on

Business Ethics: Experiential Exercises for

Exploration and Practice', JoMrna/ of Business Ethics

14, 63-70,

Green, R, M,: 1993, 'Centesimus Annus: A Critical

Jewish Perspective', Journal of Business Ethics 12,

945-954.

Hanafy, A, A. and H, Sallam: 1988, 'Business Ethics:

An Islamic Perspective', Proceedings of the

Seminar on Islamic Principles of Organizational

Behavior (International Institute of Islamic

Thought, Herndon, VA),

Jabber, P: 1986, 'Egypt's Crisis, America's Dilemma',

Foreign Affairs 62, 961-980.

Joy, A, and C, Ross,: 1989, 'Marketing and

Development in Third World Contexts: An

Evaluation and Future Directions', Journal of

Macromarketing, 17-31.

Keller, N, H. M,, trans.: 1994, Reliance ofthe Traveller

A Classic Manual of Islamic Sacred Law hy Ibn Naqib

Al-Misri (Sunna Books, Evanston, IL),

Keynes, J, A. M,: 1972, The Collected Writings of John

Maynard Keynes (Macmillan for the Royal

Economic Society, London),

Middle East Economic Digest: 1995, 'Islamic Credit

Starts Up' , 39 (21 July).

Middle East Executive Reports: 1995, 'Upgrade Plans

Boost Egyptian Market for Phone Switches', 18,

September, 12-14,

Moore, R, M, and N, Delener: 1986, 'Islam and

Work', in G, S, Roukis and P. J, Montana (eds,).

Workforce Management in the Arabian Peninsula

(Greenwood Press, Westport, CT).

Najjar, E M,: 1992, ' The Application of Sharia Laws

in Egypt', Middle East Policy 1, 62-73,

Naqvi, S. N, H,: 1981, Ethics and Economics An Islamic

Synthesis (The Islamic Foundation, Leicester).

Nyaw, M, and I. Ng: 1994, 'A Comparative Analysis

of Ethical Beliefs: A Four Country Study', Jowma/

of Business Ethics 13, 543-555,

Qur'an: undated, English translation of the meaning.

Revised version of translation by Abdullah Yusuf

Ali (The Presidency of Islamic Researches, King

Fahd Holy Qur' an Printing Complex, Saudi

Arabia).

Rawwas, M,, S, Vitell and J. Al-Khatib: 1994, 'The

Impact of Terrorism and Civil Unrest on

Consumer Beliefs', Journal of Business Ethics 13,

223-231,

Rogers, H, P, A. O. Ogbuehi and C, M, Kochunny:

1995, 'Ethics and Transnational Corporations

in Developing Countries: A Social Contract

Perspective', Jowrna/ of Euromarketing 4, 11-38,

Rossauw, G, J,: 1994, 'Business Ethics: Where Have

All the Christians GoneV, Journal of Business Ethics

13, 557-570.

Sallam, H, and A, A, Hanafy: 1988, 'Employee and

Employer: Islamic Perception', Proceedings ofthe

Seminar on Islamic Principles of Organizational

Behavior (International Institute of Islamic

Thought, Herndon, VA),

Siddiqi, M, N.: 1981, 'Muslim Economic Thinking:

A Survey of Contemporary Literature', in K,

Ahmad (ed.). Studies in Islamic Economics (The

Islamic Foundation, Leicester),

Singhapakdi, A,, K, Rallapalli, C. P Rao and S. J,

Vitell: 1995, 'Personal and Professional Values

Underlying Ethical Decisions A Comparison of

American and Thai Marketers', International

Marketing Review 12, 66-76.

Smith, N, C, andj, Quelch: 1992, Ethics in Marketing

(Richard D, Irwin, Inc, Homewood, IL).

The Economist: 1995, 'Good Grief, April 8, 57,

Thomas, K,: 1995, 'Women Who Mean Business',

Gulf Marketing Review 16, December, 35-37,

Thomas, K.: 1996a, 'Pyramid Selhng', Gulf Marketing

Review 17 (January), 28-29,

358 Gillian Rice

Thomas, K,: 1996b, 'Buy, Buy, Baby', Gulf Marketing

Review 17 (April), 22-25,

Tuma, E. H,: 1988, 'Institutionalized Obstacles to

Development: The Case of Egypt', World

Development 16, 1185-1198.

United Nations Development Program (UNDP):

1994, Human Development Report, 1994 (Oxford

University Press, Oxford),

Vasquez-Parraga, A. Z. and A, Kara: 1995, 'Ethical

Decision Making in Turkish Sales Management',

Journal of Euromarketing 4, 6186,

Vitell, S, J,, S. L, Nwachukwu andJ, H, Barnes: 1993,

' The Effects of Culture on Ethical Decision-

Making: An Application of Hofstede's Typology',

Journal of Business Ethics 12, 118,

Wilkinson, G.: 1996, 'Making the Headlines', Gulf

Marketing Review 17, 31-35,

WiUiams, O, E: 1993, 'Catholic Social Teaching: A

Communitarian Democratic Capitalism for the

New World Order', Journal of Business Ethics 12,

919-932,

Thunderbird, The American Graduate School

of International Management,

15249 North 59th Avenue,

Glendale, Arizona 85306,

U.S.A.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Atuhaire CarolineDokument44 SeitenAtuhaire CarolineHASHIMU BWETENoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5795)

- Virgo WomanDokument18 SeitenVirgo WomanChinny Chu100% (2)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Values 2017 2018 Scenario-StudentsDokument9 SeitenValues 2017 2018 Scenario-Studentsapi-366515139Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Health Benefits of Yoga For Kids Sylwia JonesDokument15 SeitenHealth Benefits of Yoga For Kids Sylwia JonesAlfonso BpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Personal RelationshipDokument19 SeitenPersonal RelationshipVirginia HelzainkaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Bonds Between UsDokument15 SeitenThe Bonds Between Usapi-361364760100% (1)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Speech Communication LecturesDokument45 SeitenSpeech Communication LecturesarvindranganathanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Bahasa Inggris LV IDokument101 SeitenBahasa Inggris LV Iutari maharaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Chapter 2Dokument19 SeitenChapter 2April MagpantayNoch keine Bewertungen

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- Sports CultureDokument9 SeitenSports CultureNanbanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Brendan Burchard Notes (High Performance Academy)Dokument22 SeitenBrendan Burchard Notes (High Performance Academy)Paul Cowen100% (4)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Pepsi ScreeningDokument16 SeitenPepsi Screeningapi-480940034Noch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Infj Personality ("The Advocate")Dokument18 SeitenInfj Personality ("The Advocate")Michelle Villanueva83% (6)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- MUET My Way!Dokument33 SeitenMUET My Way!Joanne SiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Group II, Year 1 - LP 16 - FriendshipDokument8 SeitenGroup II, Year 1 - LP 16 - FriendshipYuvraj SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sociology Aparna Tiwari 2nd SemesterDokument8 SeitenSociology Aparna Tiwari 2nd SemesterdivyavishalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Dating Coutship and EngagementDokument55 SeitenDating Coutship and EngagementJanielle GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 40 Developmental Assets Search InstituteDokument1 Seite40 Developmental Assets Search Instituteapi-316758422Noch keine Bewertungen

- 9781108798075Dokument15 Seiten9781108798075zynaatahary67% (3)

- Project 1: Friendship: 2º BachilleratoDokument6 SeitenProject 1: Friendship: 2º Bachilleratorodrigo100% (1)

- 5late Childhood Development PowerPoint PresentationDokument13 Seiten5late Childhood Development PowerPoint PresentationDanilo BrutasNoch keine Bewertungen

- If Then Algorithmic Power and Politics Taina Bucher Full ChapterDokument59 SeitenIf Then Algorithmic Power and Politics Taina Bucher Full Chaptertyson.vaughan271100% (10)

- Deviant Moon Tarot MeaningsDokument10 SeitenDeviant Moon Tarot MeaningsTanga50% (2)

- Nakshatra and Moon Sign DetailsDokument60 SeitenNakshatra and Moon Sign DetailsSagar Sharma100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- FriendshipDokument4 SeitenFriendshipPutriSyazliqaAffeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- XI Final ExaminationDokument12 SeitenXI Final ExaminationVibha SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication Skills Workbook: Self-Assessments, Exercises & Educational HandoutsDokument124 SeitenCommunication Skills Workbook: Self-Assessments, Exercises & Educational HandoutsRoxana Cirlig100% (3)

- Themes Analysis in A NutshellDokument2 SeitenThemes Analysis in A Nutshellapi-116304916Noch keine Bewertungen

- Scott 1972 ClientelismDokument24 SeitenScott 1972 ClientelismMark Louise PacisNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- IELTS Speaking Vocabulary Family & FriendsDokument5 SeitenIELTS Speaking Vocabulary Family & FriendsM_GHAREB72Noch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)