Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Gender Differences in Communication 4

Hochgeladen von

Losh Min RyanCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gender Differences in Communication 4

Hochgeladen von

Losh Min RyanCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Gender Differences in Communication 4

Communication is the means by which ideas and information are spread from person to

person. People use communication to express feelings, emotions, opinions and values, to

learn and teach, and to improve their status. Communication is therefore vital to human

interaction whether between parents and children, bosses and employees or even husband

and wife. The diversity and characteristics of those involved in any interaction can thus

affect communication. Taking account of any diversity in interaction rather than

assuming uniformity is important to achieving effective communication.

Good communication is difficult to master and can be a major source of strife in any

situation or business. Gaps in communication arise when the intended message is not

transmitted or the message is misunderstood. The resultant miscommunication is mainly

due to the different styles of communication amongst people. n order to understand the

differences of communications patterns we should begin by considering the different

elements of the communication process between the sender of the information and

receiver. n any form of communication, the sender has a message to transmit that

becomes encoded. The receiver obtains this encoded message via some medium or

channel e.g. verbal, nonverbal or written, which is then decoded and translated !as shown

in the following diagram". n order for the communication process to work both the

sender and the receiver must understand the codes. #s an example consider the encrypted

messages that were sent during $orld $ar . n order for the receiver to understand the

message, knowledge of the code was important. $e can even consider the situation of an

%nglish speaker in &apan. 'or effective communication either one or both parties should

be able to understand and communicate in the language of the other. Good and effective

communication can therefore be affected by many things including the situation, time,

culture, and gender. The assertion that gender affects communication in different ways

has been accepted by a large part of the population today. Gender differences in

communication may pose problems in interpersonal interactions leading to intolerance,

resentment, stress and decreased productivity. This is extremely critical in business

organi(ations but even more so in your everyday world and therefore an examination of

)

these differences in the first step to understanding the issues involved and moving

towards better communication.

n any study of communication, there is variability in what is meant by *communication*.

+ome individuals may consider only the verbal attributes whereas yet others will consider

nonverbal interactions ,, and the smart will focus on both. #dditionally research studies

have focused either on both the microscopic and the macroscopic levels of

communication. The microscopic level deals with performance or perception of verbal

and nonverbal behavior and the macroscopic assesses behavior on a global level !Canary

- .india, )//0". n this discussion, both verbal and nonverbal aspects of communication

will be considered.

Gender communication 1any people use the words gender and sex interchangeably,

however these words do not mean the same thing. The word sex refers to the genetic and

biological status of being male or female, while gender refers to the psychological and

social manifestations of being male or female, i.e. the socially defined, learned,

constructed accoutrements of sex, such as hairstyle, dress, nonverbal mannerisms, and

interests !2ippa, 0330". Gender therefore focuses on the social construct regarding the

behavioral, cultural, or psychological traits typically associated with one sex. t

concentrates on the roles and responsibilities, expectations, and aptitude of men and

women that are learned, and modified as a result of the interaction of culture, society and

environment.

There are two views regarding gender ,, the essentialist and the social constructionist

views !4obb, 0335". The essentialist view gender as that with which we were born, being

part of our genetic make,up. The male and female roles are therefore distinct identities

and they shape behavior. 6owever, this view might be somewhat limited since it does not

account for the masculine and feminine attributes inherent in people. The social

constructionist upholds the idea that psychological conditioning early in life leads to who

we are and become as a result of the social interactions. Therefore in this view gender is

shaped by society, culture and time.

0

$hat then is gender communication7 +everal have used the term to signify the

differences in communication due to biology and others use it to represent differences

resulting from social, psychological and cultural interactions. 'or most researchers

gender communication focuses on the expressions used by one gender in the relationships

and roles between people. The existence of a difference in gender communication has

been a topic of interest for decades with generali(ations being made between the sexes. #

large volume of work has been published both in the mainstream popular books and in

the research arena with linguistic scholars stressing the differences in communication

style. $hile a large volume of literary work on the subject exists, the findings are not

consistent and much controversy arises mainly as a result of the biased view of the

mainstream publications.

1ost published work on gender differences are believed to fall into 0 categories of bias8

alpha where the difference is exaggerated or beta which presumes that there are few if

any differences between the sexes !Canary - .india, )//0". The bias approach adopts

the view that *similarities rather than differences characteri(e men and women* and that

while *some noteworthy differences between men and women exist, when both within,

and between,gender comparisons are made9 the similarities are as important,,if not more

important,,than the differences* !Canary - .india, )//0"".

The alpha bias can be seen especially with books such as &ennifer Coates: $omen, 1en

and 2anguage, &ohn Gray:s 1en are from 1ars, $omen are from ;enus, 2illian Glass:

6e +ays, +he +ays8 Closing the Communication Gap <etween the +exes, &ulia $ood:s

Gendered 2ives, and .eborah Tannen:s =ou &ust .on:t >nderstand8 $omen and 1en in

Conversation, that have sought to explain the gender differences in communication and

fall into the category of alpha bias. &ennifer Coates !)/?@" wrote about her studies

involving gender separated discussion groups. 'rom her observations she noted that

women reveal a lot about their private lives in their conversations, stick to one topic for a

long time, let all speakers finish their sentences and try to have everyone participate. n

contrast, men discussed things other than their personal relationships and feelings, change

topics freAuently, dominate conversations and establish a hierarchy in communication

over time.

B

The hierarchical view in communication has also been emphasi(ed in scholarly work.

1ales are said to establish a status hierarchy to compete, exert control and maintain the

upper hand !%ckes, 0333". 'emales also establish hierarchies however these are based on

friendship rather than power and accomplishment !4obb, 0335".

n her book .eborah Tannen argues that men and women approach conversation with a

distinct set of rules and interpretations of talk. 1en focus on status and independence9

women focus on intimacy and connection,,a difference that makes communication

between the sexes problematic. +he states that *communication between men and women

can be like cross cultural communication, prey to a clash of conversational styles*

!Tannen, 033)".

n a similar manner to Tannen, &ohn Gray:s !)//0" book, based on participants: reports in

relationship seminars, shows a clear and polari(ed depiction of men and women. Gray:s

theory is that women use superlatives, metaphors, and generali(ations in their speech

which men interpret literally causing miscommunication between the sexes. 6e also

stated that men are more direct and straightforward in their speech.6owever he states that

in addition to a communication difference, there is a difference in thinking, feeling,

perception, reaction, response, love, need, and appreciation. #s a result his book is often

viewed as sexist by many feminists.

.r. 2illian Glass !)//0" noted over )3C sex talk differences in her book. 6er findings are

similar to those of Coates where she noted that men disclosed less personal information

and spoke more loudly than women do. +he stated that men use the techniAue of loudness

to emphasi(e points, while women use pitch and inflection for emphasis. Dther findings

were that men tended to interrupt more often than women do, make direct accusations

and statements, and ask fewer Auestions.

*Gendered lives* by $ood supports the theory that women use communication as a way

to establish and maintain relationships. $ood states that women are responsive,

supportive, value eAuality and work toward sustaining communication. +he goes on to

show the polari(ation of communication by stating that men use communication as a

5

means by which to solve problems, maintain dominance and assertiveness. 1en are less

responsive9 their talk is more abstract and less personal.

Communication styles The authors above have all promoted the idea of different styles of

communication between men and women. To this extent, there are four areas where

gender differences in communication are believed to exist. These are problem solving,

communication of feelings, needs and desires, understanding of a situation and relating to

it and the approach to situations. $hen messages are transmitted from sender to receiver,

there is a potential for distortion of the message due to how it may be perceived.

.ifferences in communication between men and women may be a result of this distortion

or differences in the style and content of the messages. The styles of gender

communication have been expressed as *debate versus relate*, *report versus rapport*, or

*competitive versus cooperative*. These different styles of communication are believed

to be the cause of miscommunication. The commonly accepted differences in these styles

of interaction can be summari(ed as shown8 Competitive E 1ake more commands E

2imited emotional content E Fuantity of speech limited E >se of slang andGor swearing E

Gives information 4elational E #sk more Auestions E .iscuss feelings and perceptions E

6igher Auantity of speech E Polite speech E ncludes more detail The work by Tannen

supports the view of *report talk* and *rapport talk* where her studies have shown that

men engage in solution oriented conversations aimed at the main issue. $omen however

were said to engage in relationship,oriented conversations that targeted to connect with

and relate to the other speaker.

Generally, the communication style of women has been described as being more

emotional than men. $omen focus on feelings and building relationships while men

focus on power, and status. This is also shown in problem solving, where men take a

straightforward approach compared with women who tend to establish intimacy, show

concern and empathy. #dditionally women are also seen to foster cooperation rather than

competition.

1en display a higher percentage of task behaviors ,, providing information, direction, or

answers, and direct disagreement than women do !%ckes, 0333". They use problem

C

solving as an opportunity to demonstrate competence, ability to solve problems and their

commitment to the relationship. $hen thinking about the problem, they expect solutions,

exerting power to accomplish the problem solving task. Dn the other hand, use problem

solving as a way to strengthen relationships, focusing on sharing and discussing the

problem rather than the end result.

Df course, not everyone feels there is a strong difference. This theory of two

communication styles has been rejected by 1ulac !)//?". 6e believes that when applied

to written work establishing a difference in communication between men and women was

difficult. 6e bases this viewpoint on a study that reported on individuals of non,%nglish

backgrounds, of different ages and social classes who were are not able to distinguish

whether written %nglish messages had been produced by males or females. 6e maintains

that if such differences exist in speech then these should be an observed difference in

writing style.

+imilar studies involving speech have been investigated to determine whether differences

can be detected in taped conversations where the sex of the speaker was unknown. The

results here are mixed with some of these studies showing no detectable difference and

some studies concluding that a difference was observed.

;erbal communication The communication differences observed between the sexes range

from verbal to nonverbal communication. $hen considering verbal communication

researchers look into speech and voice patterns while nonverbal communication

encompasses body language, facial language, and behavior Glass, )//0".

2iterature reviews of gender differences do not help either way when considering verbal

communication. The evidence shows that men are more talkative than women in mixed,

sex groups !%ckes, 0333". 1any linguists will have us believe that women are more

talkative than men. $omen are also considered to interrupt conversations and finish

sentences. 6owever there are studies that contradict the idea of interruptions as the

domain of women. +cientists have sought to rationali(e the reason for the lack of

@

agreement between studies as being a failure to define what an interruption and to

distinguish between the different types and well as the environment.

;erbal differences include the use of vulgar words, aggressiveness and a tendency to

attack the speaker, dominate and interrupt the conversation by men !%unson, 033C". Dn

the other hand, women are considered as being polite and less aggressive. 6owever,

while there are differences in the speech patterns, everyone shows varying degrees of

what is considered to be masculine and feminine speech characteristics. This raises the

issue of stereotyping and bias, and the effect of other factors that can influence speech

patterns. $ith the interaction of external and internal factors other than gender on

communication and the controversy surrounding the two language styles, it is difficult to

demonstrate differences in verbal communication based on gender only. #s a result,

nonverbal communication is seen as the area where gender differences in communication

exist.

Honverbal communication refers to those actions that are distinct from speech. Thus

nonverbal communication includes facial expression, hand and arm movement, posture,

position and other movements of the body, legs or feet !1ehrabian, 033I". Honverbal

communication or body language has been consistently shown to be different in the two

sexes !Glass, )//0".

$omen are considered to be more nonverbally warmer than men with a tendency to

smile and lean toward others during conversation. $omen also use a pleasant warm voice

in conversation that is not characteristic of conversations between men !%ckes, 0333".

.ifferences have also been noted with respect to the gestures used while speaking. 1en

are observed to use straight and sharp movements, while women tend to have more fluid

movement. n terms of posture, women tend to keep arms next to their bodies and cross

their legs while men often have an open wider posture ,, arms away from the body and

legs apart.

#nother difference lies in visual dominance, with men being considered to be more

visually dominant than women. ;isual dominance is defined as the ratio of the time spent

I

maintaining eye contact while talking to the time spent maintaining eye contact while

listening !%ckes, 0333". Df course, one needs to take into account that women have wider

peripheral vision allowing them to give the impression they are looking in one direction

while actually looking in another direction.

n communication men tend to sit other side,by,side next to each or stand at some

distance. $omen sit face,to,face with other women or stand closer, indicating a more

open and intimate position that help them connect with one another. 'or men, a face,to,

face position indicates challenge or confrontation.

Honverbal differences have been categori(ed as being8 ). primary , hereditary

characteristics of male and femaleness. n this aspect the developmental difference in

bone structures of males and females determine how they walk, their gestures, and other

nonverbal behavior. <ody shape is also considered as it relates to nonverbal

communication since it affects posture ,, larger shoulders in man, and breasts in women.

0. secondary , modeling or observation of same,sex role models. Children model the

behavior of parents and conseAuently learn to follow the patterns of same,sex role

models, boys using nonverbal movements similar to their fathers: and little girls act like

their mothers. B. tertiary , popular explanations of reinforcement or conditioning for male

or female behavior. Positive reinforcement of behavior increases the behavior, whereas

negative reinforcement decreases it and culture is thought to shape appropriate behavior

for boys and girls !Payne, 033)". n childhood play, boys are encouraged in activities that

involve rough,and,tumble play for boys and girls have been cuddling and nurtured.

#lthough this has been changing in recent times, this division still exists in some

societies and cultures.

Honverbal differences are said to exist along lines of the sex role expectations of society.

+pecific gender role nonverbal communicative behavior is learned however men and

women also use other nonverbal styles not typical of their sex for practical purposes

!Payne, 033)". 6ere the external influences of the situation may dictate the use of

nonverbal communication. Honverbal communicative behavior is also affected by

culture. 'or example the use of space varies from culture to culture, from an appreciation

?

and respect for personal space to a negation. +tudies involving the use of space as a part

of interpersonal communication recogni(es that *people of different cultures do have

different ways in which they relate to one another spatially* with spatial use defining

social relationships and social hierarchies !Payne, 033)". %xamples include the difference

in posture between manager and employee, the close proximity by #rabic speakers, and

the traditional position of the male at the head of the table in $estern society.

Hature versus nurture The concept of nature versus nurture has been used to explain the

differences in verbal and nonverbal communication. t was introduced in )?I5 by 'rancis

Galton and since then there has been a debate on which accounts for the observed

differences.

Hature relates to biological evolution, genes, hormones, and neural structures. n contrast,

nurture is related to culture, social roles, settings and learning, and stereotypes. Hature

and nurture both produce sex differences in behavior and gender,related individual

differences within the sexes. #dvances in biological psychology, neuroscience, and

molecular genetics have resulted in new findings that provide evidence on the theory of

nature versus nurture of gender !2ippa, 0330".

The influence of gender differences begins very early in childhood and can shape the

communication of style of the adult !Tannen, 033)". +tudies on children have shown that

there are language differences between boys and girls as early as preschool !%ckes,

0333". Tannen highlights differences in the way young girls and boys use language in

childhood, stating that girls make reAuests, use language to create harmony and use more

words while boys make demands, create conflict and use more actions.

The differences in adults are thought to stem from influences in childhood such as parents

and playtime instruments. n the first few years of life girls are more used to physical

touch by their mothers during childhood compared with boys. $omen therefore use

touch to express caring, empathy and emotions. n contrast, men regard touch as way to

communicate sexual interest, orders, and as a symbol of control. 1en are seen as being

/

more competitive and verbally assertive due to childhood influences of toys such as guns

and swords.

# person:s communication skills in addition to being partially genetic, are therefore also

shaped by factors such as society, culture and education. +ociety often expects that a

woman should be polite and well behaved. This stems from childhood when girls were

told that it is better to be seen and not heard.

+tatus and 4ole Dne argument that has been ongoing since the early 03th century is that

gender varies with status and role in society. %ven with the advances in thinking, there

still exists a division of labor that allocates different work and responsibilities to men and

women in societies and cultures. nteractions involving women are characteri(ed as being

that which draws out supportive, cooperative behavior, whereas men interact to elicit

dominant, directive behavior. # comparison of men and women in the same social roles

is therefore important in the investigation of whether a true gender difference exists or the

observed difference is confounded by status.

n addition, gender differences can also be accounted for by the difference in status.

4esearch has shown that aggressiveness and dominance found to dependent on status on

top of gender !#ries, )//?" and that the differences in communication are sometimes less

noticeable in men and women at the same societal level !Powell - Graves, )//?".

+ituation The context in which communication occur can have an effect dependent on

who is taking part in the interaction, i.e. the characteristics !age, race, class, ethnicity,

sexual orientation", relationships and setting. Communication between friends may be

less stilted than between strangers and acAuaintances. n the studies of differences,

strangers were grouped together and communicative behavior observed over time. +ome

may be shy, others concerned with making a good impression and yet others having a

laisse( faire attitude. These situations will not replicate interactions between families,

friends and co,workers and therefore caution should be applied in the interpretation of the

observed differences.

)3

1eaning of <ehavior 4esearchers consider interruptions to be a mechanism of power and

dominance in conversation. They use this as a benchmark to demonstrate the

pervasiveness of male dominance in daily interactions. 6owever the context in which the

interruption occurred should be considered before application of a meaning to the

behavior. nterruptions may serve many purposes ,, as a show of support, understanding

and agreement !collaboration" or as a disruption or violation of the speaker:s right of

speech !dominance". 6ence occurrences of interruptions cannot be considered without

regarding the reason and function of the interruption.

$hen status and role, culture, situation, and assigning meaning to behaviors are taken

into consideration as confounders, the magnitude of gender differences and the effect si(e

can sometimes appear to be small. Taken into context this means that while there are

some differences that can be attributed to gender, the overall magnitude of the difference

must also include the interaction of several factors.

1asculinity, femininity and communication There are contexts in which men display

feminine behavior, contexts in which women display masculine behavior, and contexts in

which the behavior of is differentiated by gender. <ehaviors that society label as feminine

or masculine are displayed by both men and women9 they are not always sex specific.

# study by 4ahman et al. !033B" found within sex differences in verbal fluency. The

researchers examined gender differences amongst heterosexual men and women, and

homosexual men and women. The results of the study showed that homosexual men and

women had opposite,sex shifts in their verbal fluency scores. To test verbal fluency,

subjects were assessed on letter, category and synonym fluency. 6omosexual men had

the highest scores on letter and synonym fluency while homosexual women had the

lowest scores for letter fluency. The differences were related to the difference in the

functioning of the prefrontal and temporal cortices of the groups.

'our theories have been used to explain gender differences in communication. These are

on the basis of biological, psychologicalGsociological, cultural, and religious differences

!Payne, 033)". The discussion will focus on culture and biological differences.

))

Culture The word culture indicates the lifestyle of the people within a group and denotes

the values, beliefs, artifacts, behavior and communication. Culture is learned being

passed down from generation to generation, providing guidance for ethical and moral

behavior. Gender communication can be considered to be a sub,culture since it is passed

down from generation in the interactions that children have with their parents and other

adults. This idea appears to validate the theory of nurture and its effect on

communication. Tannen !033)" has shown that the role of culture is critical to the

understating of the communication skills of a person. Tone, aggressive speech, and

interruption of the speaker all depend on cultural background. n #sian culture,

aggression is not considered to be appropriate behavior, with both men and women

showing politeness in their conversation with others. .epending on status, tone is used to

indicate displeasure.

+tudies have shown that preschool Chinese girls are bossy and argumentative with boys

depending on the scenario !%ckes, 0333". n the Chinese culture women are dominant in

the domestic context while men play a more powerful role in business. 4ole play in

which domestic scenes are performed show a difference in tone, language and behavior

with girls showing dominance and boys being deferent. n contrast $estern culture does

not show such a demarcation of roles.

# literature review on gender differences in &apan and the >nited +tates looked at sex,

cultures !i.e., nationality", and the interaction of sex and culture to determine which

accounted for differences in communication in men and women !$aldron - .i 1are,

)//?". The review concluded that there are not many major differences in communicative

styles between &apanese men and women. # similar study on #sians in 6ong Jong also

found that although some, there was not that many significant difference in

communication styles between the sexes. $hen the effects of culture and sex were

compared, culture appeared to be the more important variable in affecting

communication. The authors of this study concluded that sex differences manifest

themselves differently in &apan than in the >nited +tates.

)0

<iology and brain structure Gender difference in communication has been related to

biological factors. This age old theory is regarded by some as sexist since it was used in

the past centuries to subjugate women. The current view leans toward a biological basis

of sex differences in brain and behavior. This area has been developed in recent time with

an increasing numbers of studies in the behavioral, neurological and endocrinological

sciences.

That there exist differences in the male and female brain structure has been the topic of

academic research and popular books such as 1oir and &essel:s <rain +ex, where they

discuss the theory in relation to the processing of information. .ifferences in cognition

between the sexes has been documented since the last century, with males showing great

aptitude on visuospatial tasks and females scoring higher in verbal fluency tests !#llen

and Gorksi, 0330".

4ecent studies on structural differences in the brain of men and women account for the

greater verbal fluency by showing that the corpus callosum !the huge crescent,shaped

band of nerve fibers connecting the brain hemispheres" is larger in women than in men

!2ippa, 0330". +ince parts of the corpus callosum as well as the anterior commissure,

another connector, appear to be larger in women they are thought to permit better

communication between hemispheres. #nne Campbell:s !)/?/" work on brain

laterali(ation supports the theory of brain structure differences accounting for differences

in gender communication. The planum temporale, a region of the brain involved in verbal

ability has been shown to have greater symmetry in females !#llen and Gorksi, 0330".

Campbell concluded that the female brain is therefore better organi(ed for

communication being less laterali(ed with functions spread over both sides of their

brains. This she states explains the reason why women use words more expressively than

men. <ased on brain differences women are better communicators than men, a difference

that probably existed at birth.

Current research using f14 !functional magnetic resonance imaging" has shown that

differences in brain anatomy of males and females may explain differences in cognitive

behavior !Gur et al., )///". The superior performance by women on verbal and memory

)B

tasks has been explained by the difference in hemispheric speciali(ation of cortical

function. >sing this background as the basis for their study, Gur et al. !)///" found that

parallels between gender differences in cognition and differences in gray matter exists.

4esults showed that the percentage of gray matter was higher in women and in the left

language hemisphere and women outperformed men on the language tasks.

n a more recent study, researchers in 'rance have found differences amongst males and

females groups on brain activation strength linked to verbal fluency !words generation"

!Gautier et al., 033/". >sing functional magnetic resonance imaging !f14", the study

showed that there is a gender effect, as well as a performance effect, on cerebral

activation. The gender effect was found regardless of performance with men activating

several regions of the brain in comparison to women having high fluency.

These studies involving magnetic resonance imaging of the brain during problem solving

tasks provide evidence that supports the theory of brain structure and gender difference in

communication. Df course, results of studies are still being debated since some studies

are being reviewed for having yielded conflicting results.

+ome studies have shown that a difference exists in hemispheric activity in men

compared with during certain language tasks. #nd a few studies have failed to find

differences in functional asymmetry. +ince the task used in the studies may not be

comparable, then the results should be interpreted with caution since a difference in task

is shown rather than a gender difference. The Auestion of group differences in verbal

abilities which might account for neurocognitive differences elicited between men

Key Issues on Gender and Development

)5

Key Issues on Gender and Development page is a quick introduction to gender-related issues in a

particular sector. This page contains overview of the issues and a list of relevant questions to

consider.

Fragility !onflict | Governance " Infrastructure " Information and !ommunication

Technologies " #rivate $ector Development " Transport " %ater and $anitation

Fragility & Conflict

#ost conflict programs tend to target women for counseling men for &o's. (owever) effective

postconflict reconstruction efforts need to go 'eyond stereotyped methods) and use more

integrated approaches.

Gender Issues in Conflict Prevention and Post-Conflict Reconstruction

*ighty percent of the world+s ,- poorest countries have suffered from a ma&or conflict in the past

./ years. In $u'-$aharan 0frica) conflicts have taken an increasing toll on development

prospects) with almost half of all countries) and one in five 0fricans) directly or indirectly affected

'y conflict. 0s women and men have different needs and play different social and economic roles

in restoring war-torn societies) it is particularly important to ensure that post-conflict interventions

are inclusive. There is a su'stantial 'ody of literature on men+s and women+s different e1periences

of conflict that demonstrate that there are high short- and long-term costs to countries+

development if they fail to address gender-specific needs. The 2nited 3ations $ecurity !ouncil

4esolution .5,/ 6,---7 recogni8es the distinction 'etween women+s and men+s needs and calls

on all actors involved in negotiating and implementing peace agreements to adopt a gender

perspective. This perspective includes paying attention to the special needs of women and girls

during repatriation and resettlement) reha'ilitation) reintegration and post-conflict reconstruction.

Increasingly) the need to e1amine notions of 9masculinities: is also part of an improved response

to post-conflict needs.

Key Issues

Masculinity, males and conflict: Masculinity, males and conflict: ;en and 'oys are often

victims of 'rutal indoctrination during their recruitment to an armed group< this can involve forced

killings) drug a'use) and rape. ;ales commonly lose their traditional male role as providers for the

family) may find themselves displaced from their family+s homes) or 'e una'le to find employment.

$ome find status and power in se1ual violence and possession and use of weapons. #ost-conflict

programs should focus on ways to draw young men into a cohesive society) rather than on

punishing and controlling them. The latter only reinforces a cycle of e1clusion and punishment

and perpetuates violent 'ehavior.

Femininity, females and conflict: %omen are not only the victims of conflict< they are often

actively involved in the fighting. %omen represent 'etween one-tenth to one-third of all

com'atants in regular or irregular armies 6e.g.) guerilla movements7) and often participate in other

active roles) including support functions. Demo'ili8ation and reintegration programs 6D4#s7 for

e1-com'atants should represent the economic) legal and psychological needs of 'oth female and

male e1com'atants. These needs are usually not met 'ecause many women tend not to register

for D4#s for fear of 'eing stigmati8ed for their role in the conflict or for having had illegitimate

children resulting from rape. #ostwar societies go through changes and adapt) making the issue

of reintegration relevant to all mem'ers of society) not &ust to e1-com'atants. D4# planners

should therefore also analy8e the potential side-effects of the D4# on non-com'atants and avoid

any negative impacts.

Gender-ased !iolence "G!# and $I!%&ID': %omen and men are 'oth vulnera'le to G=>

)C

during conflict) al'eit in different ways. %omen are often victims of heightened se1ual a'use and

trafficking during conflict) as they are seen as a form of 'ooty 'y enemy soldiers. $e1ual a'use of

women from enemy camps is seen as a means of demorali8ing the enemy. The gender-'ased

risks of contracting (I>?0ID$ or $TDs should 'e an important aspect of post-conflict

reconstruction efforts.

Private Sector Development

#rivate $ector Development 6#$D7 plays an important role in the %orld =ank Group+s work.

Improving the investment climate and market access provides new income opportunities to 'oth

men and women in developing societies. ;oreover) markettype mechanisms may empower poor

people 'y improving the quality of 'asic social services. @et #$D effectiveness requires an

understanding of the different constraints often faced 'y women and men in this domain. Gender

considerations should thus 'e incorporated into five key #$D areasA disparities in asset

ownership< la'or market im'alances< access to finance< access to markets< and 'usinessena'ling

environment.

Disparities in asset o(ners)ipA In many countries there are gender disparities in asset

ownership. Band is often the most valued asset) and where women are constrained 'y law or

custom in owning land) they are una'le to use land as an input into production or as collateral for

credit. This is inefficient and may hamper growth. 0n e1ample of how to address this issue comes

from >ietnam) where land title certificates have 'een reissued with the names of 'oth hus'ands

and wives) giving women landuse rights previously denied to them.

*a+or mar,et im+alances: Ta'oos and pre&udices against hiring women are costly to society as

a su'stantial proportion of its productive potential is stifled. $kepticism against female workers

may hamper private sector developmentA as it restricts total la'or supply) the price of male la'or is

pushed up and artificial la'or shortages may result. In Besotho) the %orld =ank funded a

sensiti8ation program aimed at increasing female participation in road construction activities.

&ccess to financial services: Designing financial institutions in ways that account for

genderspecific constraints C whether 'y su'stituting for traditional forms of collateral or 'y

delivering financial services closer to homes) markets and workplaces C can increase access to

savings and credit and affect the relative via'ility and competitiveness of femalerun enterprises. In

parts of %est 0frica) 9mo'ile 'ankers: 'ring financial services to clients) eliminating the need to

travel in order to save and 'orrow.

&ccess to mar,ets: %omen+s seclusion from the pu'lic arena) higher time poverty) and lack of

mo'ility limit their access to markets in various ways. For instance) women usually have less

information a'out prices) rules and rights to 'asic services. In 2ganda) this type of inefficiency has

'een tackled 'y Ideas for Earning Money) a !D4om that teaches women new 'usiness skills and

'est 'usiness practices.

usinessena+lin- environment: %omen often 'enefit more than men from

'usinessena'ling environment reforms) as their 'usinesses tend to have more pro'lems with

customs) courts) 'usiness registration) ta1 rates and ta1 administration. To address this issue)

theGender and Growth Assessment tool was developed to help countries identify key investment

climate constraints for women and provide a roadmap of needed reforms) which local

organi8ations can work on implementing following assessment completion. The tool was a %orld

=ank Group effort led 'y IF! Gender *ntrepreneurship ;arkets 6G*;7 in 2ganda) and has 'een

replicated in Kenya) Tan8ania) and Ghana. The issue of women+s access to networks cuts across

all key areas. 0s social norms may discourage women from mi1ing freely with men) participation

in womenonly 'usiness associations can help women make connections) share information)

identify 'usiness opportunities) generate crossreferrals) and act as support for entrepreneurs who

)@

might otherwise feel isolated. =usiness organi8ations can also lo''y for a more

'usinessfriendly environment for women in general. In 0fghanistan) an important task for the new

;inistry of %omen+s 0ffairs was to set up the 0fghan %omen+s =usiness !ouncil) with support

from 23IF*;.

Key Issues

(ow do women+s and men+s access to assets differD 0re there gender differences in

ownership of 'ank accounts) access to credit and land) and in property lawsD

%hat is the female la'or force participation rate in a countryD (ow does men+s and

women+s participation differ in scale) sector of operation) and earningsD 0re there gender

differences in the proportion of individuals employed in the informal sectorD

0re se1 disaggregated #$D statistics availa'le at the national levelD

Information and Communication Technologies (ICT

%omen and men have different needs and constraints when accessing and using IC.. In many

societies) women+s and men+s access to and use of technology are rooted in 'ehavioral) cultural)

and religious traditionsA

!ultural and social attitudes are often unfavora'le to women+s participation in the fields of

science and technology) which limits their opportunities in the area of I!T.

%omen are often financially dependent on men or do not have control over economic

resources) which makes accessing I!T services more difficult.

0llocation of resources for education and training often favors 'oys and men.

In some societies) women+s seclusion from the pu'lic arena makes access to community

telecenters difficult.

2nless e1plicit measures are taken to address the constraints women face) advances in I!T may

increase gender disparities and their potential impact will 'e reduced.

Gender-responsive I!T can make technologies) from telephones to computers) availa'le to more

people and offer ways for 'oth women and men to access information and markets) and

participate in new income generating activities. %hen I!T policies and programs recogni8e the

different constraints women and men face) I!T will contri'ute to reducing women+s 'urden of

la'or in time consuming tasks) provide income generating activities) and provide an important

source of employment in 'oth I!T and other fields.

Key Issues

0re there gender differences in access to I!TD

(ow does the use of I!T affect men and women differentlyD (ow can I!T 'e used to

reduce gender inequalitiesD

0re 'oth men and women included in I!T decision makingD 0re gender issues

considered when setting national I!T prioritiesD

Governance

The current approach to reducing poverty and promoting economic growth stresses the need for

communities to 'e a'le to influence the pu'lic institutions that affect their well-'eing. Good

governance is central to this approachA pu'lic institutions must 'e efficient) transparent) and

accounta'le< and the processes of governance must 'e inclusive and participatory so that all

)I

citi8ens have opportunities to demand accounta'ility from their governments.

/)y Gender Issues are Relevant to Good Governance

Gender equality is an important goal in itself and a means for achieving development.

Development policies and institutions must ensure that all segments of society - 'oth women and

men - have a voice in decision making) either directly) or through institutions that legitimately

represent their interests and needs. @et) persistent and pervasive gender disparities in

opportunities) rights vis-E-vis the state and pu'lic institutions) and voice) particularly limit women+s

a'ility to participate as full citi8ens in social) economic) and political life. The e1clusion of women

from full participation constrains the a'ility of pu'lic sector policies and institutions to manage

economic and social resources effectively. $uch gender-'ased e1clusion compromises the

prospects for high-quality service delivery.

Key Issues

There are several key aspects of pu'lic sector good governance) 'ut a few of them in particular

have specific gender-relevant considerations worth e1aminingA

Citi0ens)ip: To what e1tent do policies and practices support women and men to reali8e

their duties) rights) and access to services as citi8ensD

*e-islation and enforcement: (ow do legal and &udicial systems improve the socio-

economic and legal status of women and menD (ow effectively do the legal and &ustice

sectors address women+s and men+s status and protection under the lawD

Pu+lic e1penditures: To what e1tent do pu'lic e1penditures reflect governments+ e1plicit

gender equality goals and target the delivery of high-quality services to all citi8ensD

'tructures and processes of -overnance: (ow can women+s participation in political

decision- making processes 'e reali8edD Do the structures and processes for

representation at central and decentrali8ed levels focus on including interest groups

which have previously 'een e1cludedD Do they include women in critical num'ers in key

institutions) e.g.) parliaments and local governmentsD

Delivery of services: %hat priority is given to participatory and transparent decision

makingD %hat policies can enhance institutional accounta'ility and responsiveness to

women+s specific needs for services in key sectorsD

Infrastructure

The infrastructure sector is often assumed to 'e gender neutral) with women and men 'enefiting

equally from pro&ects. Females and males) however) have different roles) responsi'ilities and

constraints) which result in gender-'ased differentials in demand for and use of infrastructure

facilities and services. The development effectiveness and sustaina'ility of the infrastructure

sector could increase significantly 'y addressing gender differences in demand and utili8ation.

This involves incorporating a gender perspective in selecting and designing infrastructure

interventions) assessing safeguards issues) and conducting monitoring and evaluation.

$*B*!TIF3 FF I3F40$T42!T24* I3T*4>*3TIF3$. 4ecogni8ing gender asymmetries in

demand affects selection of infrastructure activities to 'e undertaken in a countryA

'election of interventions across infrastructure sectors2 Back of access to certain

types of infrastructure services 6e.g.) water) sanitation) fuel and transport7 negatively

)?

affects women more than men and can act as a drain on economic growth in a

community. %omen and girls are disproportionately affected 'y lack of access to

infrastructure services since they 'ear a larger share of the responsi'ility and time for

household maintenance and care activities. Infrastructure investments within a country)

particularly those in transport) energy and water sectors) must 'e prioriti8ed 'ecause of

their potential to reduce the opportunity costs to girls and the time and energy costs to

women of their household roles.

'election of interventions (it)in infrastructure sectors2 %hich interventions are to 'e

selectedD Is there a demand for a feeder road or a trunk road 6connecting village to main

town7D $hould water connections 'e provided in village centers or in homesD The answer

depends on who is asked. !alculating the potential 'enefits of a pro&ect requires

measuring gender differences in demand. For e1ample) women have larger transport

'urdens than men and are typically the main users and providers of household water and

cooking fuel. Thus demand assessment techniques must measure gender disparities in

demand.

$0F*G204D$. For certain infrastructure sectors such as mining or power generation) gender-

relevant considerations might 'e of critical importance in the conte1t of safeguard issues) such as

environmental impacts of increased soil erosion) degradation of water quality) contamination of

drinking water systems) and so on. These environmental effects can disproportionately affect

women 'y increasing their workloads and reducing their a'ility to protect their families+ health and

well'eing. The most effective approach to safeguarding the environment would therefore 'e one

that recogni8es gender differences in roles and responsi'ilities.

;F3ITF4I3G 03D *>0B20TIF3. 4ecogni8ing gender asymmetries affects the design of

monitoring and evaluation of pro&ects. Ignoring this fact might understate or overstate the impact

of a pro&ect. *ffective monitoring requires developing indicators for each stage of pro&ect cycleA

design) implementation) outputs) impact) and for assessing changes in social and economic

characteristics of the communities affected 'y the pro&ect. 0 few e1amples of gender-sensitive

indicators areA use of gender-disaggregated data in pro&ect planning and monitoring) men+s and

women+s groups levels of engagement in pro&ect processes) promotion of men+s and women+s

initiatives 'y the pro&ect facilitator) increase in the num'er of women using intermediate means of

transport or using the time saved 'y improved access to water for other developmental purposes)

and improved access to markets for women traders.

Key Issues

%hat are the gender differences in demand for energy) water) sanitation) transport) and

I!TD %hat are the main economic) time) and cultural constraints to access to

infrastructureD

%hen setting infrastructure priorities) do policies reflect women+s and men+s different

constraints and needsD

0re 'oth women and men 'eing trained as managers and operators of community

infrastructure facilitiesD Do women and men differ in their willingness to pay 6%T#7 for

infrastructure servicesD (ow does this affect service deliveryD

0re pro&ects 'eing designed to fully incorporate an understanding of their gender-related

impactsD

Transport

=ecause women and men in developing countries have different transport needs and priorities)

they are frequently affected differently 'y transport interventions. For e1ample) Rural .ransport

)/

Pro3ects that 'uild roads for motori8ed transport often do not 'enefit rural women) who mainly

work and travel on foot in and around the village. ;oreover) the construction of roads may have

an indirect effect on women as the increased mo'ility of their male counterparts could lead to the

spread of $I!%&ID'. In fact) international evidence shows that the transport sector is a ma&or

vector for this pandemic 6$ocial analysis in transport pro&ects) ,--G7. 4r+an .ransport 'ystems)

which are designed to transport people to and from employment centers) may also respond

inadequately to the needs of women) who must com'ine income generation with household

activities) such as taking children to school and visiting the market.

The failure of the transport sector in meeting women+s needs and priorities affects women

negatively in several ways. =ecause of lack of access to adequate transport) women en&oy less

mo'ility than men< their access to markets and employment is circumscri'ed. %omen+s safety

suffers when their needs are not taken into account in transport pro&ect design) for instance due to

the a'sence of street lighting. %omen+s health is also negatively affected 'y the lack of adequate

transport. *very minute a woman dies in child 'irth) 'ut many of these deaths 6and the disa'ility

caused 'y o'structed la'or7 could 'e avoided with timely access to transport 6Gender and

transport resource guide) ,--G7.

Furthermore) poor women) who 'alance productive) social) and reproductive roles) often have

higher demands on their time than poor men. Gender-responsive infrastructure interventions can

free up women+s time 'y lowering their transaction costs. This) in turn) increases girls+ school

enrollment and facilitates women+s participation in income-generation and decision-making

activities. *vidence from #akistan shows that an all-weather motora'le road may increase girls+

primary school enrollment 'y /- percent and female literacy 'y H/ percent 6Dalil *ssakali) ,--/7.

0ddressing transport-related gender inequalities is smart economics. It 'enefits society as a

whole. 4educing women+s time costs and increasing their mo'ility and safety increases women+s

productivity which makes society as a whole more productive. Gender-responsive transport

services can thus serve as a powerful vehicle to achieving several of the ;DGs. They help

empower women) improve health) provide education opportunities and ultimately reduce poverty.

Key Issues

%hat are the gender differences in demand for transportD

%hen setting transport priorities) do policies reflect men+s and women+s different

constraints and needsD

Is transport pro&ect design and implementation 'ased on consultations with women as

well as menD

%hat transport pro&ects 'enefit women as well as men the mostD

!ater and Sanitation

%omen and men generally have very different roles in water supply and sanitation 6%$$7

activities. These differences are particularly evident in rural areas. Fften women are the main

users) providers) and managers of water in rural households. %omen are also the guardians of

household hygiene. ;en are usually more concerned with water for irrigation or for livestock.

(ence women tend to 'enefit most when access to water) and the quality and quantity of water

improves. Improvements in %$$ infrastructure are likely to shorten women+s and girls+ time spent

carrying heavy containers to collect water) there'y freeing up their time for incomegenerating

activities and school attendance) respectively. Given their longesta'lished) active role in %$$)

women generally know a'out current water sources) their quality and relia'ility) any restrictions to

their use) and how to improve hygiene 'ehaviors. @et for many years) efforts to improve %$$

services had a tendency to overlook women+s central role in water and sanitation. %hile women

03

were often more direct users of water C especially in the household C men traditionally had a

greater role than women in pu'lic decisionmaking. It is essential to fully involve 'oth women and

men in demanddriven %$$ programs) where communities decide what type of systems they want

and are willing to help finance. (aving 'oth men and women involved makes sense for two

reasonsA

First) evidence shows that women+s participation is highly correlated with %$$ pro&ect

effectiveness. $econd) the 'enefits from incorporating gender aspects into the %$$ sector will not

only accrue to women)'ut also to men. Improvements in %$$ infrastructure will help increase

women+s human capital) reduce their time constraints) allow for new incomegenerating activities)

and improve community health. This will in turn increase the productivity of society as a whole)

there'y creating new income. (ence) improving %$$ services makes economic sense for men as

well as for women.

Key Issues

%ho is voicing community preferences on the selection of %$$ technologies) facility

sites) arrangements for financing and management of water servicesD

0re 'oth men and women discussing water and sanitation pro'lems and possi'le

solutionsD

Do e1tension teams have men and women on themD Do they target men and women+s

groups separately for consultation) if local cultures differ significantly 'etween women and

menD

0re 'oth women and men 'eing trained as managers of community facilitiesD

#ermanent 24B for this pageA httpA??go.world'ank.org?I@J0KF5JK-

Home |

Site Map |

Index |

FAQs |

Contact Us |

Search |

RSS

2013 The World Bank Group, All Rights Reserved. egal

0)

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Intrapersonal Communication: Pragmatic LanguageDokument2 SeitenIntrapersonal Communication: Pragmatic LanguageHina KhanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nonverbal CommunicationDokument7 SeitenNonverbal CommunicationShashank Nimesh100% (1)

- Nonverbal CommunicationDokument11 SeitenNonverbal Communicationapi-26365311100% (2)

- How Your Birth Order Influences Your Life AdjustmentDokument1 SeiteHow Your Birth Order Influences Your Life AdjustmentChad MaxxorNoch keine Bewertungen

- English - Intercultural CommunicationDokument12 SeitenEnglish - Intercultural CommunicationAlexandra NevodarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender InequalityDokument21 SeitenGender InequalityJoshua B. JimenezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender-Role Stereotypes in Integrated Social Marketing Communication: Influence On Attitudes Towards The Ad by Kirsten Robertson, Jessica DavidsonDokument8 SeitenGender-Role Stereotypes in Integrated Social Marketing Communication: Influence On Attitudes Towards The Ad by Kirsten Robertson, Jessica DavidsonGeorgiana ModoranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Non-Verbal Communication Provide The Context of Verbal ExpressionDokument5 SeitenNon-Verbal Communication Provide The Context of Verbal ExpressionAlya FarhanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- BusComm MidtermDokument93 SeitenBusComm Midtermalyssa19calibara03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Field Version of UMF Unit-Wide Lesson Plan TemplateDokument7 SeitenField Version of UMF Unit-Wide Lesson Plan Templateapi-385925364Noch keine Bewertungen

- LANGUAGE & GENDER PrsentationDokument22 SeitenLANGUAGE & GENDER PrsentationUmaima KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication Privacy Management CPM TheoryDokument31 SeitenCommunication Privacy Management CPM TheoryRenzo Velarde0% (2)

- Chapter 2 - Culture & Interpersonal CommunicationDokument7 SeitenChapter 2 - Culture & Interpersonal CommunicationMuqri SyahmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpersonal SpeechDokument34 SeitenInterpersonal SpeechisraeljumboNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Understanding Different Communication StylesDokument8 Seiten1 Understanding Different Communication StylesAndrew Dugmore100% (2)

- Community Participation and e M P o W e Rment: Putting Theory Into PracticeDokument74 SeitenCommunity Participation and e M P o W e Rment: Putting Theory Into Practiceclearingpartic100% (1)

- Gender Differences in CommunicationDokument10 SeitenGender Differences in Communicationعرفان احمدNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural Dimensions of Global Is at IonDokument26 SeitenCultural Dimensions of Global Is at IonbemusaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication StylesDokument5 SeitenCommunication StylesKilaparthi Keertika0% (1)

- Social Media Is Sabotaging Social Skills and Relationships Essay RevisedDokument4 SeitenSocial Media Is Sabotaging Social Skills and Relationships Essay Revisedapi-236965750Noch keine Bewertungen

- Purposive Communication: Unication Principes and EthicsDokument47 SeitenPurposive Communication: Unication Principes and EthicsYnah Suarez0% (1)

- Gender and Politeness in EmailsDokument32 SeitenGender and Politeness in Emailsbersam05Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Rhetorical AppealsDokument5 SeitenThe Rhetorical Appealsapi-100032885Noch keine Bewertungen

- Non Verbal Communication & Five Person Communication NetworkDokument26 SeitenNon Verbal Communication & Five Person Communication NetworkMuzamilNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpersonal CommunicationDokument17 SeitenInterpersonal Communicationmill0% (1)

- What Is Interpersonal CommunicationDokument4 SeitenWhat Is Interpersonal CommunicationBhupendra SharmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conquering Your Fear of Speaking in PublicDokument29 SeitenConquering Your Fear of Speaking in PublicIrtiza Shahriar ChowdhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reader ResponseDokument2 SeitenReader ResponseLuke WilliamsNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Use of Non - Verbal Communication in The Teaching of English LanguageDokument6 SeitenThe Use of Non - Verbal Communication in The Teaching of English LanguageJOURNAL OF ADVANCES IN LINGUISTICSNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gender and Language PDFDokument15 SeitenGender and Language PDFVanessa Namakula100% (1)

- Nature of Interpersonal CommunicationDokument24 SeitenNature of Interpersonal CommunicationJerome Vargas100% (1)

- Why Is Intimacy An Adolescent Issue?Dokument18 SeitenWhy Is Intimacy An Adolescent Issue?cranstoun100% (1)

- Reflective Writing - Gender Class and InclusionDokument4 SeitenReflective Writing - Gender Class and Inclusionapi-487664247Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Seven Dimensions of CultureDokument8 SeitenThe Seven Dimensions of CultureAnirudh KowthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cross-Cultural Training: Sharon Glazer, Ph.D. San Jose State UniversityDokument22 SeitenCross-Cultural Training: Sharon Glazer, Ph.D. San Jose State UniversityFaisal Rahman100% (1)

- What's Wrong With The Following Print Ads?Dokument50 SeitenWhat's Wrong With The Following Print Ads?Teacher MoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersDokument11 SeitenThe Role of Nonverbal Communication in Service EncountersPadmavathy DhillonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Life Without Stigma: A SANE ReportDokument36 SeitenA Life Without Stigma: A SANE ReportSANE Australia100% (5)

- Module 2 Lesson 1Dokument26 SeitenModule 2 Lesson 1JAYVEE MAGLONZONoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 8 Chapter 7 Sociolinguistics Gender & Age FixDokument20 SeitenGroup 8 Chapter 7 Sociolinguistics Gender & Age FixArwani ZuhriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agenda Setting TheoryDokument12 SeitenAgenda Setting TheoryAngela OpondoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intro To Comm MediaDokument28 SeitenIntro To Comm MediaCarleenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Be A Good ListenerDokument2 SeitenBe A Good ListenerAy AnnisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Communication Is A Process of Transmitting Information From Origin Recipients Where The Information Is Required To Be UnderstoodDokument10 SeitenCommunication Is A Process of Transmitting Information From Origin Recipients Where The Information Is Required To Be Understoodal_najmi83Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 The Moral PersonDokument39 SeitenChapter 4 The Moral PersonJane WongNoch keine Bewertungen

- EDUC 202 Social Dimensions of Education: Intercultural CommunicationDokument51 SeitenEDUC 202 Social Dimensions of Education: Intercultural CommunicationAngelNicolinE.SuymanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Training - CommunicationDokument16 SeitenTraining - CommunicationVishal SawantNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment 1Dokument2 SeitenAssignment 1api-322231127Noch keine Bewertungen

- Eapp Concept PaperDokument10 SeitenEapp Concept PaperNicole MonesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Group 8AGender Politeness and StereotypesDokument20 SeitenGroup 8AGender Politeness and StereotypesKrystal Joy GarcesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Listening & Critical ThinkingDokument18 SeitenListening & Critical ThinkingHana Takeo HataNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intercultural CommunicationDokument9 SeitenIntercultural Communicationdrama theater100% (1)

- Politness and Face TheoryDokument17 SeitenPolitness and Face TheoryArwa Garouachi Ep Abdelkrim100% (1)

- Local and Global Communication in Multicultural SettingDokument26 SeitenLocal and Global Communication in Multicultural SettingJoshua Liann EscalanteNoch keine Bewertungen

- History of Rhetoric PowerPointDokument17 SeitenHistory of Rhetoric PowerPointRana Abdul HaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Culture in Verbal and Non Verbal CommunicationDokument2 SeitenCulture in Verbal and Non Verbal Communicationputri kowaasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verbal and Non Verbal CommunicationDokument36 SeitenVerbal and Non Verbal CommunicationMonica MarticioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapeutic Relationship NotesDokument11 SeitenTherapeutic Relationship NotesAlexandra StanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interpersonal Communication NotesDokument3 SeitenInterpersonal Communication NotesJorgeaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Male FemaleDokument32 SeitenMale FemaleDimple SandiegoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conflict Ass 2Dokument12 SeitenConflict Ass 2Losh Min RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- HRD 829 Course Outline 21Dokument4 SeitenHRD 829 Course Outline 21Losh Min RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intern Cover LetDokument1 SeiteIntern Cover LetLosh Min RyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Labour Economics Notes HRM 201Dokument23 SeitenLabour Economics Notes HRM 201Losh Min Ryan64% (11)

- Thomas Edison College - College Plan - TESC in CISDokument8 SeitenThomas Edison College - College Plan - TESC in CISBruce Thompson Jr.Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reclaiming The Now: The Babaylan Is Us: Come. Learn. Remember. HonorDokument40 SeitenReclaiming The Now: The Babaylan Is Us: Come. Learn. Remember. Honorrobin joel iguisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apple Organizational BehaviorDokument2 SeitenApple Organizational Behaviorvnbio100% (2)

- Research Report: Submitted To: Mr. Salman Abbasi Academic Director, Iqra University, North Nazimabad CampusDokument14 SeitenResearch Report: Submitted To: Mr. Salman Abbasi Academic Director, Iqra University, North Nazimabad CampusMuqaddas IsrarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Strategic Thinking Part1Dokument15 SeitenStrategic Thinking Part1ektasharma123Noch keine Bewertungen

- To The Philosophy Of: Senior High SchoolDokument25 SeitenTo The Philosophy Of: Senior High SchoolGab Gonzaga100% (3)

- Schopenhauer On Women QuotesDokument1 SeiteSchopenhauer On Women QuotesclewstessaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abbreviated Lesson PlanDokument5 SeitenAbbreviated Lesson Planapi-300485205Noch keine Bewertungen

- Environmental Phase I Checklist (ASTM E 1527-05 / X4) (Indicate With A "Y" or "N" Whether The Info. Is Included in The Phase I)Dokument3 SeitenEnvironmental Phase I Checklist (ASTM E 1527-05 / X4) (Indicate With A "Y" or "N" Whether The Info. Is Included in The Phase I)partho143Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nigredo by KeiferDokument3 SeitenNigredo by KeiferchnnnnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarDokument172 SeitenThe Glass of Vision - Austin FarrarLola S. Scobey100% (1)

- Improving Students Mathematical Problem Solving Ability and Self Efficacy Through Guided Discovery 39662Dokument12 SeitenImproving Students Mathematical Problem Solving Ability and Self Efficacy Through Guided Discovery 39662nurkhofifahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yoga Sutra PatanjaliDokument9 SeitenYoga Sutra PatanjaliMiswantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nanna-About The Soul Life of Plants-Gustav Theodor FechnerDokument47 SeitenNanna-About The Soul Life of Plants-Gustav Theodor Fechnergabriel brias buendia100% (1)

- Hegel and The OtherDokument333 SeitenHegel and The OtherJulianchehNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unfree Masters by Matt StahlDokument42 SeitenUnfree Masters by Matt StahlDuke University Press100% (1)

- What Do You Know About Our Company?: Why Did You Apply For This PositionDokument6 SeitenWhat Do You Know About Our Company?: Why Did You Apply For This PositionWinda NurmaliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Essays - M AKRAM BHUTTODokument17 SeitenSample Essays - M AKRAM BHUTTOAnsharah AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Life and Works of Rizal - Why Study RizalDokument4 SeitenThe Life and Works of Rizal - Why Study RizalTomas FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- AbstractDokument25 SeitenAbstractMargledPriciliaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Basketball Practice MindsetDokument4 SeitenBasketball Practice MindsetBrian Williams0% (1)

- Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Dokument3 SeitenSarvepalli Radhakrishnan Biograph1Tanveer SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment Draft - Indra GunawanDokument2 SeitenAssessment Draft - Indra Gunawanpeserta23 HamidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature 7 Explorations 4th Ed LpoDokument11 SeitenLiterature 7 Explorations 4th Ed LpoTetzie Sumaylo0% (1)

- Marriage As Social InstitutionDokument9 SeitenMarriage As Social InstitutionTons MedinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 33 Degrees in Free MasonryDokument6 Seiten33 Degrees in Free Masonrylvx6100% (1)

- The Mission of The ChurchDokument6 SeitenThe Mission of The ChurchasadrafiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Naturalism, Consciousness, & The First-Person Stance: Jonardon GaneriDokument26 SeitenNaturalism, Consciousness, & The First-Person Stance: Jonardon Ganeriaexb123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Integrated Operations in The Oil and Gas Industry Sustainability and Capability DevelopmentDokument458 SeitenIntegrated Operations in The Oil and Gas Industry Sustainability and Capability Developmentkgvtg100% (1)

- Legal OpinionDokument2 SeitenLegal OpinionJovz BumohyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsVon EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (387)

- The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveVon EverandThe Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and LoveBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (384)

- Lucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindVon EverandLucky Child: A Daughter of Cambodia Reunites with the Sister She Left BehindBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (54)

- The Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryVon EverandThe Masonic Myth: Unlocking the Truth About the Symbols, the Secret Rites, and the History of FreemasonryBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (14)

- You Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsVon EverandYou Can Thrive After Narcissistic Abuse: The #1 System for Recovering from Toxic RelationshipsBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (16)

- Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusVon EverandUnwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to CampusBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (22)

- Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityVon EverandGender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of IdentityBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (317)

- Feminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionVon EverandFeminine Consciousness, Archetypes, and Addiction to PerfectionBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (90)

- Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsVon EverandBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of PlantsBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (1424)

- Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouVon EverandPeriod Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For YouBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (25)

- Abolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureVon EverandAbolition Democracy: Beyond Empire, Prisons, and TortureBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (5)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamVon EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (60)

- Unlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateVon EverandUnlikeable Female Characters: The Women Pop Culture Wants You to HateBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (18)

- Decolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationVon EverandDecolonizing Wellness: A QTBIPOC-Centered Guide to Escape the Diet Trap, Heal Your Self-Image, and Achieve Body LiberationBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (22)

- Survival Math: Notes on an All-American FamilyVon EverandSurvival Math: Notes on an All-American FamilyBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (13)

- Tears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalVon EverandTears of the Silenced: An Amish True Crime Memoir of Childhood Sexual Abuse, Brutal Betrayal, and Ultimate SurvivalBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (136)

- The Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamVon EverandThe Longest Race: Inside the Secret World of Abuse, Doping, and Deception on Nike's Elite Running TeamNoch keine Bewertungen

- The End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyVon EverandThe End of Gender: Debunking the Myths about Sex and Identity in Our SocietyBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (126)

- Summary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedVon EverandSummary: Fair Play: A Game-Changing Solution for When You Have Too Much to Do (and More Life to Live) by Eve Rodsky: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedBewertung: 5 von 5 Sternen5/5 (1)

- The Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbuseVon EverandThe Courage to Heal: A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual AbuseNoch keine Bewertungen

- From the Core: A New Masculine Paradigm for Leading with Love, Living Your Truth & Healing the WorldVon EverandFrom the Core: A New Masculine Paradigm for Leading with Love, Living Your Truth & Healing the WorldBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (16)

- Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him FreeVon EverandScoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him FreeBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (19)

- Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism 2nd EditionVon EverandAin't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism 2nd EditionBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (382)

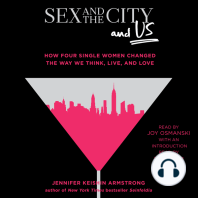

- Sex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveVon EverandSex and the City and Us: How Four Single Women Changed the Way We Think, Live, and LoveBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (22)

- Crones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenVon EverandCrones Don't Whine: Concentrated Wisdom for Juicy WomenBewertung: 2.5 von 5 Sternen2.5/5 (3)