Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

SEEP Vol.7 Nos.2&3 December 1987

Hochgeladen von

segalcenterOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

SEEP Vol.7 Nos.2&3 December 1987

Hochgeladen von

segalcenterCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

VOLUME 7, NOS .

2 ' 3

DECEMBER, 1987

and

D :rama T'heatre

.. ' . , I

and

F 'ilm

SEEDTF is a publication of the Institute for Contemporary

Enstern European Drama and Theatre under the nuspices of

the Center for Advanced Study in Theatre Arts (CASTA) ,

Grndunte Center, City University of New York with support

from the National Endowment for the Humanitites. The

Institute Office is Room I 206A, City University Graduate

Center, 33 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036. All sub-

scription requests and submissions should be addressed to the

Editors of SEEDTF: Daniel Gerould and Alma Law, CASTA,

Theatre Program, City University Graduate Center, 33 West

42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

EDITORS

Daniel Gerould

Alma Law

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Richard Brad Medoff

ADVISORY BOARD

Edwin Wilson, Chairman

Marvin Carlson

Leo Hecht

Copyright 1987 CASTA

SEEDTF has a very liberal reprint ing policy. Journals :-.nd

newsletters which desire to reproduce articles, reviews, :-.nd

other materials which have appeared in SEEDTF m:-.y do so,

as long as the following provisions are met:

a. Permission to reprint must be requested from SEEDTF in

writing before the fact.

b. Credit to SEEDTF must be given in the reprint.

c. Two copies of the publication in which the reprinted

material has appeared must be f urnished to the Editor of

SEEDTF immediately upon publication.

2

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Editorial Policy ............... .......................................... S

Subscription Policy .... ....................... ........................ 6

Notes from the Editors ........................................ ..... 7

Announcements ........................................................ 8

"Theatre in Moscow:

The 1986-1987 Season." Alma Law ...................... l5

"Yugoslavia: Even Summer Theatre

Carries on the Business of Politics:

Dragan K lait ........................................................... 20

"Eastern European Films."

Leo Hecht ................................................................. 24

"Andrei Tarkovsky 1832-1986." .............................. 30

"Kierkegaardian Motifs in

Tarkovsky's The Sacrifice"

Peter G. Christensen ..... ...... ..................................... 31

"Alcksandr Sokurov: Ma11's

Lo11el )' Voice . ........................................................ .40

"Zbigniew Cynkutis 1938- 1987."

Marc Robinson ........................................................ .42

"Piwnica Pod Baranami--A Cabaret

from Poland." Teodor Zareba ................................. .44

"Folktheatre in Poland."

Steven Hart ............................. ........................... ...... .46

3

"An Absurdoid Evening in

Binghamton." Eugene Brogyani. .................... .. .. 51

"Polished Polish Performances:

Without Benefit of Translation."

Glenn Loney ........................................................ 54

"On Radzinsky's Joggi11g.

Alma Law ............................................................ 62

"The Poetry of Infidelity."

Lisa Portes ........................................................... 64

Book Reviews ..................................................... 70

Contributors ............................................... : ........ 73

Playscripts in Translation Series ........... ............ 74

4

EDITORIAL POLICY

Manuscripts in the following categories are solicited:

articles of no more than 2.500 words; book reviews; p r ~

formance and film reviews; and bibliographies. It must be

kept in mind that all of the above submissions must concern

themselves either with contemporary materials on Soviet or

East European theatre. drama and film, new approaches to

older materials in recently published works. and new per-

formances of older plays. In other words, we would welcome

submissions reviewing innovative performances of Gogo! or

recently published books on Gogo!, for example, but we could

not use original articles discussing Gogo! as a playwright.

Although we welcome translations of articles and

reviews from foreign publications, we do require copyright

relense statements.

We will also gladly publish announcements of special

events. new book releases, job opportunities and anything else

which may be of interest to our discipl ine. Of course all sub-

missions are evalunted by blind readers on whose findings

acceptance or rejection is based.

All submissions must be typed double-spaced and

carefully proofrend. Submit two copies of each manuscript

and attach a stamped, self addressed envelope. The Chicago

Manual of Style should be followed. Transliterations should

follow the Library of Congress system. Submissions will be

evaluated, and authors will be notified after approximately

four weeks.

All submiss ions, inquires and subscription requests

should be directed to:

Daniel Gerould or Alma Law

CASTA, The.atre Program

Graduate Center of CUNY

33 West 42nd Street

New York. NY 10036

5

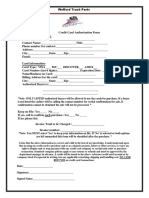

SUBSCRIPTION POLICY

SEEDTF is partially supported by CASTA and The

Institute for Contemporary Eastern European Drama and

Theatre at The Graduate Center of the City University of

New York. The $5.00 annual subscription pays for a portion

of handling, mailing and printing costs.

The subscription year is the calendar year and thus a

$5.00 fee is now due for 1988. We hope that departments of

theatre and film and departments of Slavic languages and lit-

eratures will subscribe as well as individual professors and

scholars. The $5.00 check should be made payable to

"CAST A, CUNY Graduate Center" and sent to:

CAST A, Theatre Program

CUNY Graduate Center

33 West 42nd Street

New York, NY 10036

Subscription to SEEDTF, 1988.

NAME:

ADDRESS:

AFFILIATION;

(if not included in address above)

6

NOTES FROM THE EDITORS

Begi nning with thi s issue, SOVI ET AND EAST-

EUROPEAN DRAMA., THEATRE, AND FILM returns to the

Center f or Advanced Study in Theatre Arts (CAST A) at the

City University Graduate Center where it was originally con-

ceived seven years ago as a project of the NEH Humanities

Institute for Contemporary Eastern European Drama and

Theatre with support from the National Endowment for t he

Humanities.

In assuming responsibility for the continued publica-

tion of SEEDTF, we would like to express our deep gratitude

to its founding editor, Professor Leo Hecht, Chairman, Rus-

sian Studies, George Mason University, who with great energy

and enthusiasm has transformed what was originally a modest

newsletter into a full-fledged periodical, published three times

a year. We would also like to take this opportunity to thank

George Mason University for its continued support in assist-

ing with the printing and mailing costs of the publication.

In spite of a very heavy academic schedule, Leo Hecht

has consistently--and almost single-handedly--brought to

SEEDTF's readership a wealth of information on Soviet and

East European cultural activities. SEEDTF is unique in

making available news on what is happening right now. In

this respect, we share Leo's belief that the publication fills a

void left by the more academic journals in the Slavic and

performing arts fields where the lag time is considerably

greater, and the popular press which must spread its reporting

over a much larger field. Judging from the comments of

SEEDTF's readers, the immediacy of the information is one

of its strongest points and one that we also intend to

emphasize.

In taking over the editorship of SEEDTF, it is perhaps

appropriate to remind our readers that we welcome, indeed,

we need the help of each of you in bringing to our attention

for publication any and all information concerning Soviet and

East-European drama, theatre, and film, including perform-

ances here and abroad, related conferences and exhibitions.

We are especially eager to have write- ups of productions and

films you have seen while traveling or studying in Eastern

Europe or the Soviet Union as this information is simply not

available anywhere else. We also welcome brief reviews of

new books and videotapes related to performance and will

gladly publish announcements of special events, job

opportunities and other news which may be of interest to our

readership.

Daniel Gerould and Alma Law

7

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Recent Events

Hanna Krall's play about the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising,

To Steal a March on God, was presented as part of The

Spring Play-reading Series of the Theatre Project at The

Third Floor Studio Theatre of R. A.P.P. Arts Center, New

York City, on May 17, 1987. The producing company,

Dramatic Risks, under the direction of Mark Grant Waren

also gave stage readings of Love, Nets and Traps, and Come

into the Kitchen, three one-act plays by Liudmila

Petrushevskaya, and Edvard Radzinsky's Joggi11g on April II,

all in translations by Alma Law. Jogging is scheduled for

full production in January; for more information check the

listing in "Upcoming Events."

The McGolrick Park in Brooklyn was the site for

three outdoor presentations of The Polish Theatre Institute.

Two Polish Augusts, a tribute in prose, poetry and song to the

Polish Home Army of World War II on the 43rd anniversary

of the rising of Warsaw, and Solidarity, dedicated to the

Polish Solidarity movement on the 7th anniversary of its birth

were both performed on August 19, 1987. One week later,

August 26, the third presentation "In Pursuit of Liherty ... "

was performed. This program was a salute to the American

and Polish Constitutions and consisted of music, mostly vocal,

poetry, and prose from the end of the 18th century to the

present day and included a performance by The Polish

American Folk Dance Ensemble. For more information, see

the listing in "Upcoming Events."

The first Soviet play about Chernobyl, Sarcophagus

was written by the science editor of Pravda, Vladimir

Gubaryev. First published in the literary monthly Znamya,

the play has already appeared in ten productions in the Soviet

Union (see Alma Law's article "Theatre in Moscow: the

1986-1987 Season" in this issue of SEEDTF) Foreign stagings

have taken place in Vienna, Stockholm, and in London by

The Royal Shakespeare Company. This past September the

play opened simultaneously in the same translation by Micheal

Glenny at the Yale Repertory Theatre in New Haven, Con-

necticut and on the other coast in California at the Los

Angeles Theatre Center.

Kazimierz Braun inaugurated his tenure .as Head of

the Acting Program at the State University of New York at

Buffalo by directing the American premiere of Tadeusz

8

R6zewicz's The Hu11ger Artist Departs in a translation by

Adam Czerniawski. The cast included both professional

actors and students with the role of "The Author" being

played by the Polish playwright, actor, and director Stanislaw

Brejdygant. The play ran from April 23 to May 3, 1987 and

was advertized using a poster designed by Polish Artist

Krystyna Jachniewicz. On April 24, Rozewicz discussed his

work at a lecture on campus. During his visit ot the U.S.

Rozewicz also addressed the Polish Institute of Arts and

Sciences of America, in New York City.

The Manhattan Theatre Club presented Janusz

Gtowack i's Hu11ti11g Cockroaches translated by Jadwiga

Kosicka at the New York City Center during the Spring 1987

season. It was directed by Arthur Penn who also directed this

play at the Ma rk Taper Forum in Cali fornia. At the Mark

Taper Forum it ran from November to Dectember. For those

who missed these productions, there are several productions

planned around the country listed in the "Upcoming Events."

Opening in March and running through May, 1987;

Witkiewicz's The Shoemakers joined the repertory at the Jean

Cocteau Theatre in New York; it was directed by Wlodzimierz

Herman (from Denmark) who had directed the famous Pol ish

production in 1965 at the WrocP.lw student theatre Kalambur.

The stage design was by the well-known Polish artist Jan

Sawka (now in the U.S.)

On October 9, the Graduate Center of the City Univ-

ersity of New York was the scene of a performance by

MASTFOR II, a group started by Mel Gordon and Alama

Law dedicated to the preservation of the early Soviet avant-

garde. They presented a reconstruction of the third-act

cabaret from Good Treatme11t For Horses. Originally per-

formed in 1922, Nikolai Foregger's celebrated Russian Con-

structivist production combined the eccentric and risque

costume-design talents of Sergei Eisenstein and Sergei Yut-

kevich with the satiric writing of Vladimir Mass. This scene

included a demonstraion of Foregger's grid of 100 mechanical

acting movements called It was performed in

conjunction with an exhibit of costumes and set designs called

Moscow /922: Avame-Garde Per/orma11ce. Designed and

executed by Piotr Zaleski, the exhibit could be seen in the

Graduate Center Mall from October 6 to December 4, 1987.

From November 10-17, 1987, The Museum of Modern

Art in New York presented a film series, "New Voices from

the Soviet Cinema." The seven features and three short sub-

9

jects fell into two categories: films banned and shelved for as

long as twenty years and recent works that indicate new art-

istic d irections. Included in this series were: A. Sokurov's

Man's Lonely Voice (1978, reviewed i n this issue); N.

Djordjadze's Robinsonada; or My English Gra11d/ather

(I Qft6), about a Briton building a telegraph line in Georgia

during the turbulent twenties, and his thesis film Joume.v to

Sopot; S. Ovtscharov's Belie'ie II or Not (1983), a fairy-tale

comedy based on traditional motifs of Russian fol klore; Cen-

tral Asian filmmaker B. Sadikov's pol itical allegory Adonis

XIV (1977); V. Tumaev's A Visit 10 a Son (1986); newcomer

Y. Mamin's short feat ure Neptu11e's Holiday (1986); Y. Pod-

niek's outspoken documentary Is It Easy To Be roung?

( 1986); and Viktor Ogorodnikov's look at the contemporary

punk music scene of Leningrad's teenage subculture in The

Burglar (1987). The series was organized by Jytte Jensen.

In Brief:

Running from August through October, The CAST

Theatre in Hollywood presented Joumey ittto the Whirlwind,

based on Yevgenia Ginsburg's memoirs, adapted and per-

formed by Rebecca Schull.

Livieu Ciulei directed Shakespeare's Coriolanus at the

McCarter Theatre in Princeton from November 4 to 22.

Blanka Ziska produced and directed Charles

Marowicz's t ranslation of lonesco's Macbet t at the Wilma

Theatre, Philadelphia. It opened for a limited run on Novem-

ber 15.

The Department of Theatre Arts at Bethel College in

St. Paul, Minnesota presented the American premiere of

Kazimierz Braun's The Plague. It was directed by Jeffrey

Miller and ran from October 14-24.

As part of the Next Wave Festival at the Brooklyn

Academy of Music, Peter Sellars directed za,gezi: Super-

saga in 20 Planes by Russian Futurist poet Velimir K hleb-

nikov. It was originall y produced in May 1923 at the

Museum of Artistic Culture in Leningrad, with stage design

by t he Constructivist sculptor, Vladimir Tatlin. Sellars's

production, which began a limited run on November 24,

1987, was first staged in December, 1986 for the opening of

the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Upcoming Events

Janusz Glbwacki's Hunting Cockroaches, directed by

Doug Finlayson, will be performed from February 17 to April

10 at Wisdom Bridge Theatre, Chicago. The play will find

10

another home at The Alley Theatre, Houston, from March 26

to May 8. A third production of the play is in the process of

being scheduled by the Odyssey Theatre Ensemble, Los

Angeles.

The Odyssey will also produce Witkiewicz's The

Shoemakers directed by Kazimierz Braun. It is scheduled for

their December-February slot, with the official opening on

January 16, 1988.

The Puppet Master ofl:.od1, written by Gitter Sigal

and translated by Sara O'Connor, will be produced by the

Milwaukee Repertory Theatre April 29 to May 15.

The Dallas Theatre Center wilt produce Fred Cur-

chuck's production of Uucle Vau.va from February II to

March 6. Lucian Pintele will direct The Cherrv Orchard for

the Arena Stage in Washington, D.C .. This production is due

to run from April 29 to June 5. Laurence Senelick's new

translation of The Cherry Orchard opens at the Ensemble

Repertory Theatre of Los Angeles on April 15, staged by the

company's new artistic director David Kaplan. Beginning

Jnnuary 18, The Cherry Orchard directed by Peter Brook will

be performed at the Brooklyn Academy of Music for a 12-

week run. This production was originally created in Paris.

The American cast includes Brian Dennehy, Linda Hunt,

Erland Josephson and Natasha Perry

Maria Irene Fornes will direct Uucle Vauya for the

CSC Repertory, New York. It will run from December 6 to

Jnnuary 2. From February 7 to March 5, the CSC will house

Diderot's Rameau's Nephew directed by Andrei Delgrader.

Karel The White Plague, translated by Michael

Heim, will be presented at the North Light Theatre,

Evanston, Illinois, from February 10 to March 13.

J.R. Sullivan's production of Strider will be performed

at the Illinois Theatre Center in Park Forest from Mnrch I to

April 3.

Witkiewicz's Couutry House, translated by Daniel

Gerould and directed by Paul Berman, will be given at

Barnard College in March, 1988.

Director Tengis Abuladze's 1984 film about Stalinist

dictatorship, Repenta11ce, is due to open in New York in

December. It is under consideration for the Academy

A ward's Best Foreign Film A ward.

The films of Zanussi will be shown at the Museum of

Modern Art from December 18 to January 31.

The Polish Theatre Institute is now accepting bookings

for their current and upcoming concert/readings and

productions. These include: "/11 Pursuit of Liberty ... ";

Three Polish Emigratio11s, narrative, poetry, and song in

11

English and Polish from the Great Emigration of the 19th

Century, post World War II, and the Present; The Eleven

Days ;, October, this program presents reports, poetry, and

songs during the time that the Polish people waited for news

about f:ather Jerzy Popieluszko, with excerpts from the

Priest's homilies; and two programs by Leon Schiller, using

the Polish actor Kazimierz Kaczor and Polish singers Jolanta

Rajewska and Krzysztof Milczarek, Pastora/ka (a shepherds'

Nativity with music) and Shop of Songs (a story of Polish

song from 16th Century to the Present). For further informa-

tion contact Nina Polan, The Polish Theatre Institute, 16 West

64th Street #58, New York, NY 10023, (212) 724-9323.

Alma Law's translation of Radzinsky's Joggi11g is to

be produced by Mark Grant Waren's Dramatic Risks . At

press time the production is scheduled for opening on January

27, 1988 to be directed by Virlana Tkacz at the R.A.P.P. Arts

Center Main Stage Theatre. 220 East 4th Street, New York.

Because of changes in the group's affiliation, it would be best

to contact Dramatic Risks directly at 60 East 4th Street # 19,

New York, NY 10003 (212) 353-1965 for the latest update.

Michael Andrew Miner, Artistic Director of Actors

Theatre of St. Paul, has announced the establishment of a

sister theatre relationship with Moscow's Ermolova Theatre.

The artistic exchange will begin during the 1988-89 theatre

season, when Miner will direct in Moscow and Yermolova's

Artistic Director, Valerie Fokin, will direct at Actors Theatre.

The following season, 1989-90, an exchange between the two

acting companies is planned. Actors Theatre recently pro-

duced the first World Premiere of a contemporary Soviet work

outside of the Soviet Union with their production of Break-

fast With Strangers in September and October. Playwright

Yladlen Dozortsev travelled from the Soviet Union to see the

production.

Another Minnesota company, the Children's Theatre

Co. of Minneapolis, will be exchanging productions and art-

istic staffs with Moscow's Central Children's Theatre next

fall. Central Theatre artistic director A. Borodin and manag-

ing director Sergey Remizov will visit Minneapolis in March

and ship one of their productions to CTC in September 1989

to open CTC's 25th season. Borodin will return in March

1990 to direct a play in rnglish with the CTC cast, while

later that year CTC is exp."ted to send one of its own prod-

uctions to the Soviet Union for performances in Moscow and

Leningrad.

12

Professor Laurence Senel ick of Tufts University has

notified us that The American Council of Learned Societies-

Soviet Ministry of Culture Commission on Arts and Arts

Research has recently been expanded, in cooperation with

IR EX. The expansion includes a new Sub-Committee on

Theatre and Dance, whose mandate is to promote culural

exchanges in those fields. This does not include ordinary

scholarly research or the kind of large-scale exchange of per-

formers traditionally carried out by impTesarios. Rather,

those projects are solicited which involve the interpenetration

of research into arts creation, performance, presentation.

Among the types of projects suggested are symposium series,

exchange of materials, joint publications or preparation of

exhibits, and the mutual interchange of choreographers,

dramatists and critics. The American members of the sub-

committee are Kalman Burnim (Chairman), President of the

American Society for Theatre Research; Marvin Carlson,

Executive Officer of the Ph.D. in Theatre at the Graduate

Center of CUNY; Laurence Senelick of Tufts University;

Selma-Jeanne Cohen, Editor of The International

Enc_l'clopedia of Dance; Martha W. Coigney, Director of Inter-

national Theatre Institute of the United States; Adrian Hall,

Artistic Director of the Dallas Theatre Center and Trinity

Repertory Company; and Bruce Marks, Artistic Director of

the Boston Ballet. Projects should be keyed to specific

sponsoring groups or institutions, and any suggestions

addressed to Professor Kalman A. Burnim, Department of

Drama and Dance, Tufts University, Medford, MA 02155.

Grad Teatar/ Theatre City Budva is a foundation,

established by the National Theatre Subotica and Municipality

of Budva, a town in the south of the Yugoslav Adriatic coast,

with two main fields of activity: Theatre City Budva/ Festi-

val takes place in July and August in various venues of the

old core of Budva and its environs, while Theatre City

Budva / School operates from September to June --as a

research and educational facility that offers various programs

and projects. The Skola is international in the composition of

its participants and staff and interdisciplinary in its approach

to theatre, with four main lines of activity: education of

theatre professionals and of other specialists- -seminars,

labs; research projects, undertaken with interdis-

ciplinary Yugoslav or international teams; collection, process -

ing and disseminaton of data on theatre life; and publishing

of a newsletter in English about ongoing and future programs

of the Foundation.

With its various programs, the School connects Yugos-

lav and foreign theatre professionals and specialists of related

13

disciplines (sociologists, psychologists, architects, urban plan-

ners, economists, etc. ); stimulates research in theatre praxis

and theoretical work on t heatre; promotes Yugoslav theatre

abroad; and serves as a place of continuous and alternative

theatre education, for theatre collectives and individual artists.

The School is headed by Dr. Dragan K laic, Associate

Professor, University of Arts Belgrade (Ho Si Mina 20, 11070

Belgrad, tel. 0 II 135 684, ext. 89).

For more information, National Theatre Subotica, lve

Vojnovica 2, 24000 Subotica, Yugoslavia, tel. 3824/ 23 431,

telex YUFESTYU 15053.

Grad theatre/ theatre City Budva, Skupstina opstine

Budva, 86000 Budva, Yugoslavia, tel. 3886/ 44 070 I 44 062,

telex YUOIUBD 61194.

14

TIIF.ATRE IN MOSCOW: THE 1986-1987 SEASON

by Alma Law

After the sensation of the 1985-1986 season, Moscow

auditnces found Lis past season somewhat tame. If they

were hoping for even greater "openness" in the airing of long-

forbidden topics than they had relished in such productions as

Aleksandr Misharin's expose of provincial corruption in Silver

AnnivNsnry at MXAT, Mikhail Shatrov's political debate of

Leninist ideas, Dictatorship of Conscience, at the Moscow

Lenin Komsomol Theatre or Speak at the Ermolova Theatre

based on Valentin Ovechkin's sketches of rural life just

before and after Stalin's death, they were bound to be disap-

pointed. As the editor-in-chief of Dru;hhn narodOI' com-

mented not too long ago, "You can't surprise anyone today

with (productions like this]. because the newspapers are

reporting more contrO\'ersial matters than are covered in the

plays being staged." In fact, the main topic of conversation

among theatregoers this past season seemed to be, not what

was on stage, but the rise in ticket prices introduced by many

theatres as part of a two-year experiment launched January I

to give theatres greater freedom in managing their repertories

and finances.

Several critics have even ventured the opinion that this

has been one of the least interesting seasons in a long, long

time. Dull? Uninteresting? With Beckett's Krapp's Last

Tape at the Mossoviet, Waiting for Godot at the Ermolova and

lonesco's The Chairs at the Stanislavsky Theatre? But , of

course, many of these productions have been around a long

time in studios and rehearsal rooms so that for the dedicated

theatre buff they can hardly be considered new.

Of greater intert>st, are the numerous Polish plays that

have made their appearance including Mrozek's long banned

The EmigrEs at the Theatre-Studio "Chelovek," and Janusz

Krasinski's black comedy, Death in Installments, about two

prisoners, who in order to delay being executed, keep con-

fessing to new crimes, each confession giving them another

lease on life. Arthur Miller is enjoying a revival with prod-

uctions of lncidelll at Vichy and The Crucible already on the

boards and a production of After the Fall scheduled for this

season at the Moscow Gogo! Theatre. House on the Embank-

ment is once again in the repertory of the Taganka Theatre

where the new chief director, Nikolai Gubenko, has promised

to restore all of the theatre's banished productions including

Alive and Boris Godunov. Nikolai Erdman's The Suicide is also

back at the Satire Theatre, this time not in Sergei Mikhalkov's

watered-down adaptation that was shown a half dozen times

15

albeit without some of Erdman's pearls of humor," as one

critic noted.

As for contemporary plays, as in the film industry, by

the end of the season, the shelves had just about been cleared

of productions. Virtually everything that has been banned or

in extended rehearsal over the past five years (and in a few

cases even longer) is now already before the public or in

rehearsal. This includes Viktor Rozov's The Little Boar

[Kabanchik), which had its national premiere at the Russian

Theatre in Riga (under the title By the Sea)and has now also

opened at the Vakhtangov Theatre in Moscow, directed by

Adolph Shapiro from the Riga Theatre of the Young Spec-

tator. After being roundly vilified at a closed session of the

Union of Writers when he first submitted this play in 1982,

Rozov is now being praised for being one of the first to deal

honestly with the moral and social effects of corruption

among top-level officials.

Liudmila Petrushevskaya's plays are at long last

making their way into the professional theatres, as are also

those of other lesser-known talents, including Andrei

K uternitsky, Nina Sadur and Liudmila Razumovskaya.

Although, as is the case with so many newer playwrights,

directors continue to misread their works as deeply realistic.

Aleksandr Galin's very stageable plays are also begin-

ning to show up all over Moscow. His The Toastma.Her at the

Moscow Art Theatre, directed by Kama Ginkas, is set in the

banquet room of a restaurant where a wedding celebration is

taking place. The highlight of the production is the duel of

toasts between a failed actor who has been hired to provide

the toasts, and Revaz, a guest at another wedding party, who

is a born toastmaster. For this funny-sad "group portrait" of

contemporary life, Ginkas has placed the cast of more than

f ifty actors in front of a huge mirror that reflects not only

everything on stage, but the audience as well.

As the season closed, another of Galin' s plays, The

Wall, premiered at the "Sovremennik" Theatre. Roman Yik-

tiuk is responsible for staging this hilarious Pirandellian game

in which the audience watches a group of actors in a provin-

cial theatre rehearsing a play and in the process loses all sense

of what is real and what is part of the production.

Edvard Radzinsky's I'm Standi11g b.v a Restaura11t (also

known as To Kill a Man) at the Mayakovsky Theatre is

another exercise in theatre within theatre. This time it's a

duel in a loft apartment between a lonely actress and her

hner, a director, in which to the very end the audience can't

be quite sure whether she is trying to kill him with her

poisoned mushrooms or simply playing a clever game of

psychological revenge. (See my commentary to Lisa Portes

16

article in this issue for a review of Radzinsky's other

premiere this season, Jogging.)

Several of Mikhail Roshchin's more satirical plays

have been brought out of limbo, including his "Aristophanes.H

or the Production of the Comedy. "Lysistrata" ill 4/1 B.C. in

Athens which was banned in 1983 for being too pacifist, and

his comedy The Seventh Labor of Hercules, about how Her-

cules succeeded in clean ing out the Auge_an stables. Written

in 1963, it was staged for the first time this season by the

new "Sovremennik-11" headed by Oleg Efremov's son Mikhail.

The production of Roshchin's sat iri cal Mother of Pearl

Zinaida, after six years of on again-off again rehearsals at

the Moscow Art Theatre, is also due to open during the com-

ing season.

Perhaps the season's most noteworthy production is

Getta Yanovskaya's staging for the first time of Bulgakov's

Heart of a Dog at the Moscow Theatre of the Young Spec-

tator (TIUZ). Yanovskaya immediately found herself in the

middle of a heated controversy over whether this was suitable

fare for teenagers, a charge she summarily rejects by arguing

that it's high time young people were offered something other

than simple-minded contemporary plays and watered-down

versions of the classics. But everyone seems to agree that this

vastly underrated director, in recreating the atmosphere and

bite of Bulgakov's 1925 parable of the Russian Revolution,

has produced one of the artistic sensations of the season.

Without fanfare, Aleksei Kazantsev has taken actors

from various theatres to stage a production of his play, Great

Buddha. Help Them! The playwright, himself, characterizes

the work as, "a political parable about how contemporary Fas-

cists hiding under leftist slogans deceive people and attempt

to turn them into the blind instruments of their [the Fascists')

power." Those who saw one of the several performances for

select audiences were quick to praise it. One observer called

it, "a cross between Orwell's 1984 and Evgenii Zamiatin's We,

and while the play is ostensibly set in Kampuchea [Cambodia)

everyone reads it as about totalitarianism in the Soviet

Union."

One of the paradoxes of the season is the absence in

Moscow, or for that matter in any major Soviet city, of a

production of The Sarcophagus by Pravda science editor

Vladimir Gubarev about the nuclear accident at Chernobyl.

Gubarev has denied that the play was sent to the West as a

Soviet propaganda maneuver, and asserts that productions are

being planned for both Moscow and Leningrad. But thus far,

after opening in Tambov, it has only appeared in a number of

other provincial cities such as Krasnoyarsk and Tiraspol near

the Black Sea. Meanwhile, Sarcophagus has already been

17

staged in Vienna at the Volkstheatre where it was highly

praised in the press for its frank criticism of the Soviet

bureaucracy, and in London at the Royal Shakespeare. The

play, which could more accurately be characterized as a piece

of "didactic theatrical reportage," has also been included in

this season's production schedule at both the Mark Taper in

Los Angeles and the Yale Repertory Theatre.

As the new season unfolds everyone is eagerly await-

ing the production now in preparation at the Vakhtangov

Theatre of Shatrov's The Peace Treaty of Brest-Litovsk:

Written twenty-five years ago as a film scenario, it was

originally to have made its stage debut at the Moscow Art

Theatre in the late 60s. But the times weren't ripe then for

portraying Nikolai Bukharin and Leon Trotsky as Lenin's

faithful disciples and Efremov was forbidden even to rehearse

the play. In its current version The Peace Treaty is clearly

intended to reflect Lenin's support for Gorbachev's peace

plan (Lenin to Trotsky: " ... what do we need today--war

or peace? Always---peace ... "). It is being directed by

Robert Sturua, chief director of the Rustaveli Theatre, in

celebration of the 70th anniversary of the Revolution. That

Sturua was chosen for the production has ironic connotations

for it was Sturua's production of another Shatrov play about

Lenin, Blue Horses 011 Red Grass, that was summarily banned

from further performances in Moscow following the showing

of it at the Maly Theatre on the opening night of the

Rustaveli's tour in September 1980. Not surprisingly, the

bureaucratic watchdogs were not all pleased to find three

Lenins on the stage, including one who dances to a Viennese

waltz. Not only that, but it was Shatrov who, after praising

the production when he saw it in Tbilisi, was forced to play

the heavy and demand that the theatre withdraw it. As

Sturua wryly commented in recalling the incident, "We

Georgians have a somewhat different way of viewing Lenin."

Also in the works are productions of Chingiz Ait-

matov's controversial novella The Executioner's Block and

Anatoly Rybakov's autobiographical novel set in the 1930's,

Children of the Arbat. Undoubtedly, other productions will

also appear to challenge the limits of Hg/asnvstH or openness.

Much of what has been staged thus far has been a matter of

putting before the public what everyone already knew but

couldn't say outloud. The real test will come when

playwrights and theatres move into new territory. There are

already signs that the limits are being set. Gorbachev him-

s.-lf, in a meeting with prominent members of the press in

July warned that "openness and democracy ... do not mean

that everything is permitted .... Openness is called upon to

strengthen socialism, the spirit of the people, to strengthen

18

the moral atmosphere in our society. Openness also means

criticism of shortcomings. But it does not mean the

undermining of socialism and of our socialist values."

Some critics have also joined in to suggest that

"enough is enough," and are calling for more genuinely

theatrical works. There are already the fi rst signs in Moscow

that interest in going to the theatre is dropping and th:lt

theat r es may soon be facing the same problem of empty

auditor iums that have already plagued provincial cit ies for a

number of years. At the moment, it is not clear to anyone

just what audiences want these days in the face of what

television, the newspapers and magazines such as Ogonek have

to offer. Perhaps the current season will provide some ans-

wers.

(Alma Law completed this article in September, just

before she left for a four-month research trip to the Soviet

Union.]

19

YUGOSLAVIA: EVEN SUMMER THEATRE CAR-

RIES ON THE BUSINESS OF POLITICS

by Dragan Klaic

Despite the worsening economic situation and inner

political conflicts that strain Yugoslavia and its many nation-

alities, theatre remains a vital realm of public life in the

country. Inflation may reach over 100 percent, troubles with

the Albanian minority in Kosovo province may stir up pas-

sions, disputes about the new constitution heat up, and new

scandals involving corruption and abuse of public investment

funds break out daily, and yet major theatre productions con-

tinue to attract audiences and offer the stage as a forum for

important public debate and as a place of collective soul

searching in these trying times. Even in the summer months

this is not a theatre of light entertainment, but of intellectual

vigor and polemic energy.

At the beginning of the summer, most repertory

theatre companies usually close their doors, but independent

theatre groups and many festival ensembles start their busy

season. From Ljublijana, in the northwest, where drama,

ballet, and opera are offered in a former Cloister near a

monument to the unknown soldier of the Napoleonic army, to

Ohrid in the south of Macedonia, where programs are given

in a former medieval church at this lake resort, festivals old

and new cater to tourists and to local theatregoers and even to

some foreigners on vacation. Various open air venues, city

SQll ares, fortresses, courtyards and even some more

unorthodox sites are turned into stages and every summer a

director comes up with a newly discovered environment to

serve his production concept.

This past summer, Split festival had major troubles in

securing some of these sites and had to cancel a scheduled

production of Oedipus Rex in a bitter conflict with the

Catholic church authorities and heirs of Ivan Mestrovic over

the use of a chapel decorated by this sculptor. For a prod-

uction of Shakespeare' s Tempest t he Dubrovnik summmer fes-

tival brought the aud iences by small boats to the nearby

island of Lokrum, a public beach during t he day. This co-

production with the Yugoslav Drama T heatre of Belgrade

certainly had a superb ready-made set for Prospero's tropical

island, but apparently the production had trouble muscling

enough acting strength to match it. In Dubrovnik's Old City,

Calder6n's Life Is A Dream was directed by Duran Jovanovic

as a gesture in praise of personal freedom against the threats

of an on111ipottnt state and arbitrary political might. And the

International University Sport Games, held in Zagreb in J ul y,

provided an excuse (and public funds) for an international

20

series of avant-garde t heatre product ions f rom abroad.

In the north of the country, i n Subotica, which

became a major theatre center two years ago when the direc-

tor LjubiYa Ristic took over the flagging local rep company, a

festival took place. Ristic and his choreographer

Nada Kokotovic offered a Do11 Jua11 , entirel y set on a real

lake shore, whe re the Spanish gala11 and h is serva nt met'l all

their opponents amidst a crowd of rust ic natives who worship

an enormous monument to the slain Come,idador- - a kind of

exotic totem pole, a reminder of past authority now gone and

rejected. A melancholic Tartuffe was set in a real amusement

park, with Orgon updated and downgraded to its tired owner

and Tartuffe made a marginal , charming, irresistible tramp

with a few magic tricks of his own. Both productions end in

speedy departures and ambiguous victories: Don Juan rows in

a small boat to Hades or to new adventures, after the monu-

ment burns down, while Tartuffe makes a hasty escape in a

pick-up truck with Orgon' s wife. While these two prod-

uctions could be seen as celebrations of personal sense of

freedom in a society that increasingly praises self reliance as a

cure for its many current troubles, a Misanthrope directed by

set on a tennis court, turned the self-righteous

rhetoric of the play's characters into a series of smooth, slow-

motion tennis movements. The tennis etiquette became a

form of social mimicry, a choreographed display of non-

chalance, an ultimate form of pervasive social insincerity. A

School for Wives with strong satiric tones completed this

series of Moliere productions, that is, in fact, a second phase

o f a Subotica endeavor star ted in the summer of 1986 with

seven Shakespeare productions--all staged in the open, in the

parks and terraces of a tur n-of -the-century resort at nearby

Palic lake.

This summe r, however , has greatly expanded

h is o peration by open ing an additional p roduct ion c ente r ,

Kotorart , in Kotor, a town on the Montenegr ia n Ri viera,

known as the si t e o f the 19 17 Austrian sai lors' rebellion

(memorial ized in Fredrich Wolf's pacifist play, The Sailors of

Callaro). In Kotor, a dozen productions by young di rectors,

some with international casts, opened in brisk sequence in

early July. The Kotor and Moliere series, together wi th last -

year's Shakespeare productions, were the core of a festiva l

t h at Subot ica th e atre organized in Bu dva, ano t her

Montenegrian resort. Both Kot or a nd Budva have rece nt ly

re novated t heir old q uarters heavily damaged in the 1979

earthquake. Ambit ious local governments, eager to upgrade

t he ir tour ist offerings with some unique cultural events, f ound

a willing pa rtner in Rist ic and his t heatre. Subot ica theatre

and the municipality of Budva set up a foundation- - Theatre

21

City Budva--that will be financed by a special tax, assessed

on a daily basis, on all tourists in the area and thus have

funds to offer the festival in the summer months and run a

theatre education and research center throughout the year.

With the local governments of Subotica, Budva, and

K otor solidly behind him, Ristic could sign up more cities in

a growing network that have bought packages of his prod-

uctions. They knew that Ristic could assemble the best talent

for productions that would attract much attention, bring

audiences, and publicity. All together some two dozen prod-

uctions had over 200 environmental performances in 60 days.

YU Fest, as the whole network was named, is not only an

entrepreneurial coup and an operation of mind-boggling

logistics; but, it is also an undertaking of clear political

importance that in many regards surpasses the artistic merits

of any particular production. In a federal state where six

republics and two autonomous provinces tend to look after

their own turf, pursue their own political priorities, and

where competing and often irreconcilable economic interests

turn into political conflicts and potentially dangerous ethnic

strife, YU Fest brought artists from all parts of the country

together, despite the reigning cultural parochialism, and

turned this festival into a symbol of Yugoslav cultural and,

indeed, theatrical unity. This movement of theatre profes-

sionals, who joined forces in a virtual grass-roots manner, is a

rebuke to the impotence and self -centeredness of the cultural

bureaucracies of the federal units which otherwise hold the

purse strings for culture-- Yugoslavia has no federal ministry

of culture, and no money for arts from the federal budget.

The novelty is that the municipalities dared to avoid their

respective superiors on the state level and joined forces

directly with each other and with teams of theatre artists,

breaking local monopolies and discarding the usual patronage

of the local talent.

YU Fest enjoyed broad media coverage and for the

most part a supportive press, eager to demonstrate to their

readers that, in a country where seemingly nothing works

properly anymore and all Yugoslav initiatives seem doomed

from the beginning, some major effort, uniting the talent of

different cultures, languages, and nations, still can be success-

ful. There were opposing voices too. Belgrade's daily Borba

greeted the August run of YU Fest productions in the capital

with two sarcastic articles that attacked Ristic and his shows

as fluff and as an expensive extravaganza for the gullible.

Y.-t, Politika, Belgrade's foremost daily, praised the undertak-

ing, in a lead article in its culture and arts supplement only a

few days later, as an encouraging example amidst an outpour-

ing of bad political and economic news that tends to make

22

most artists and intellectuals passive and resigned. The news

magazines and TV stations in Zagreb, Belgrade, and elsewhere

were equally supportive.

Some time will be necessary to j udge t he full impact

of the YU Fest--political, artistic, and financial, but Ristic is

alreadv announcing a series of new Yugoslav plays for next

summer and more municipal i t i es a re eager to join the

network. The Subotica theatre, which made a successful tour

in May to West Germany and West Berlin, has an invitation

for the Cervantino f esti val in Mexico, and contemplates a

U.S. appearance. Meanwhile, negot iations are underway to

revive in West Berlin Ristic's mega-production of Madach.

Commentaries, done originally in several urban venues at the

start of his Subotica tenure.

While this is being written, in early September, Bel-

grade is getting ready for the 21st BITEF festi val, the annual

parade of the international avant-garde. This year the impor-

tance of theatre in Yugoslav politics is being confirmed in a

curious way: the appearance of the Israeli Habima Theatre at

BITEF is perceived by many as an equivalent of the famous

U.S./China ping-pong diplomacy, a prelude for there-

establ ishment of Yugoslav-Israeli relations which had broken

off 20 years ago. The Israelis are bringing Kafka's Trial

directed by the British Steven Berkoff, and Babel's Sunset

directed by the Russian Yuri Lyubimov. The exiled director

is not expected to attend. Pity, as he could meet, in the cozy

atmosphere of Belgrade, some of his former Moscow col-

leagues who will appear at the Bitef festival in the Taganka

Studio production of Slavkin's Cercau directed by Vasilyev.

Dragan Klaic, a long-time collaborator of Ljubila

Ristic, avoided most of the YU Fest hassle by hiding out t his

past summer in the Van Pelt Library of the University of

Pennsylvania

23

EASTERN EUROPEAN FILMS

by Leo Hecht

On previous occasions a number of articles and

reviews discussing recent Soviet films have appeared in

SEEDTF. but only on rare occasions has contemporary East-

ern European cinema received the same attention.

Unfortunately. this is due to the fact that Soviet f ilms appear

to be much more in demand by American audiences. with the

rare exceptions of political films such as Wajdas Mall of /roll.

There are frequent "Soviet Film Festivals" and special show-

ings of Soviet film series. but very few similar occasions for

films from Eastern Europe--if one does not count special

programs at the Smithsonian Institution. the American Film

Institute, and various institutions of higher learning. This

article is intended, to some small degree. to rectify the over-

sight. at the request of many readers of SEEDTF, and to

present a number of important films released during the past

two decades. most of which are available for rental. All are

in their original language, i.e., Polish. Hungarian, and Serbo-

Croatian, respectively, and have English subtitles;

Polish Films

Identification Marks: Nolle, 1964, directed by Jerzy

Skolimowski. The director. himself, stars as a loafer with

poetic pretensions who lives off of his wife's earnings, unsuc-

cessfully attempts to evade being inducted into the army, and

in general avoids any social interaction within the Pol ish

system. Skolimowski made this film as a student in the .t.6di.

Film Institute. His style has been characterized as a mixture

of Orson Welles and cinema-verite.

Walkover. 1965. also directed by Jerzy Skolimowski.

This film continues the development of the hero of his

previous film, who. after his military service, works as a

hustler at amateur boxing contests and travels throughout the

country. Technically more polished than its predecessor, this

film is a bit more incisive and ironic. Its basic theme remains

one of alienation. Skolimowski's later films include Deep Elld

and The Shout.

Everything for Sale, 1968, directed by Andrzej Wajda,

is a highly personal film concerned with Zbigniew Cybulski, a

superb actor and star of Wajda's film Ashes and Diamonds,

who had died in an accident several months previously. The

entire ! ilm is dominated by the off -stage presence of the star.

It is a film about making a film whose star is killed halfway

through its completion to the great despair of the director.

Landscape After Battle, 1970, was also directed by

24

Andrzej Wajda. It tells a love story set against a background

of post-World War II chaos. Liberated Polish concentration

camp inmates find themselves stranded in a Displaced Persons

Camp where psychologically they feel neither free nor

imprisoned. The main protagonist, an intellectual with

memories of horror, hides behind his books until he is forced

back into reality by a Jewish refugee girl.

Matr of Marh/e, 1977, directed by Andrzej Wajda, is

the investigation into a man's life undertaken by a woman fit-

maker. The man was Mateusz Birkut, a now forgotten figure

of the 1950s who had been made a celebrity as part of the

government's effort to create "heroes of labor" as an example

for other workers. This epic film (nearly three hours long),

concerns itself with the relationship between political

propaganda and art and between the intelligentsia and the

working class.

Without Anesthesia, 1978, was directed by Andrzej

Wajda. This intimate, poignant film is about a foreign cor-

respondent who returns home from abroad and finds that his

wife has left him for a young writer. Against everyone's

advice, the correspondent fights the divorce action and sear-

ches unsuccessfully for the reasons of his wife's infidelity.

Provincial Actors, 1979, is an early work by a young

woman director, Agnieszka Holland. It tells the story of a

second-rate theatre troupe, its difficulties in the staging of a

classical play with a young, overzealous director from War-

saw, and the disintegrating relationship between its leading

actor and his wife, an unsuccessful actress who works in a

puppet theatre. All this is related in an agreeably open-ended

behavioral, semi-vrite style which is geared toward flow

rather than structure, and is ideally suited to describe the

bustling matrix of backstage life: gossip, backbiting, horse-

play, grumbling, quar.rels, exhibitonism, excitement, and

frayed nerves. Director Holland deftly captures the hap-

hazard and precarious lives of artists suspended in a volatile

zone between greatness and mediocrity.

Contract , 1980, directed by Krzysztof Zanussi, is an

ambitious, polyphonic comedy centering on a two-day wed-

ding reception among haute bourgeoisie. The plotline details

a steady stream of insults, embarrassments, and bruised feel-

ings which finally escalate into a series of scandals and

debacles--the bride runs off, the groom goes berserk, the

house catches on fire. All of this is rendered with the driest

of wit, an elegant and precise style and an excellent acting

ensemble including Leslie Caron as a grande dame."

Zanussi' s most remarkable achievement, however, is his

ability to balance farce with scathing social commentary.

Beneath the sparkling satire the film contains an eerily

25

prophetic vision of a deteriorating society.

The Constant Factor, 1980, also directed by Zanussi,

concerns itself with a young, excessively idealistic electrician

who yearns for the purity of mathematics and the Himalayan

peaks, where his father, a mountain climber, had mysteriously

lost his life. Instead, he finds himself severely shaken in a

world filled with petty corruption, confusion, disease and

unfairness. He is a believable and original character who is

exasperating yet oddly noble in his obstinate refusal to con-

form.

The Orchestra Conductor, 1980, directed by Wajda,

stars John Gielgud as a famous conductor, who, after 50 years

abroad, returns to his native Poland to guest conduct. The

story of his partly triumphant, partly embarrass ing return,

including his attempts to escape mounting political pressures,

is the director's eloquent statement on the artist's commitment

to his art and the individual's personal need for integrity,

even when faced with the reality of exile.

Aria for an Athlete, 1980, directed by Filip Bajon, is a

picaresque tale of a 19th century village boy with a strong

body and little intelligence, who wants to make a name for

himself in the world. The story is told in a flamboyant

rococo style full of extravagances.

Camera Buff, 1980, directed by Krzysztof Kieslowski,

is a film about an obsession with film. It starts innocent ly

with a father buying a movie camera so that he can film his

baby daughter. Next, he is asked to use his camera to docu-

ment propaganda events at his plant. He then becomes

obsessed with the realization that the camera lens sees and

records the truth. He commences to photograph things that

are upsetting to the authorities and suffers for it. This film

contains elements of slapstick mixed with sati re and political

nonconformity.

Shivers, 1981, directed by Wojciech Marczewski, was

made during the "Solidarity " period and supressed during the

subsequent crackdown. It is set in the early 1950's and con-

cerns itself with the experiences of a teen-age boy who is

sent to an elite indoctrination center for future Party

memebers. It portrays vivid imagery of an off -balance world

filled with transitions, cynicism, adolescent yearnings, reli-

gious mysticism and political zealotry.

Hungarian Films:

ll'he11 Joseph Returns, 1976, was directed by Zsolt

who made this film with a quietly feminist

understanding of human relationships. reveals

characters caught in a flux of feelings, events, and situat ions

26

which are strikingly modern and socially complex. The fil m

follows the uneasy progress of two women who are

awkwardly thrown together when the newlywed wife of a

young merchant marine comes to live with his mother after

he is sent out to sea.

Nine Months, 1977, was directed by Marta Meszaros

who is strongly identified as a femi nist fil maker. The f il m

describes the love affair between a strong-willed woman and

an impulsive, arbitrary fellow worker in an industrial ci ty.

The director's feeling for environment --stunning factory-

scapes of snow and smoke--is matched by her sensit ivity to

the sensual chemistry and emotional fluctuations of the cen-

tral relationship. Her style leans heavily towards closeups and

hands and faces are used with expressiveness and intensity.

Women, 1971, is the best known film of director Marta

Meszaros. It is the story of a friendship between a passionate

young rebel and an older woman who is disillusioned with her

well-ordered married life. It stars Marina Vlady in one of

her most important roles.

Rain or Shine, 1977, is a comedy directed by Ferenc

Andr5s . It is the story of a country family's efforts to

entertain visitors from the city on the day of a great celebra-

tion. One witnesses a steady procession of small mortifica-

tions and missed connections until a general air of acute

embarrassment settles over the entire affair.

The Stud Farm, 1978, was directed by Andras Kov5cs.

It takes place in the early 1950s and is a penetrating study of

the Stalin era as seen on a personal, savage level. The setting

is a horse-breeding farm and focuses on the tensions between

the new manager, an inexperienced young villager, and the

entrenched, hostile ex-officers of the previous generation.

The image created by depicting horses rushing at each other,

biting, and kicking, suggests that this human struggle, also, is

a matter of life and death.

Angi Vera, 1979, was directed by Pal Gllbor. It takes

place in 1948 during the period of confusion and political

reorganization. The title heroine, a naive but earnest woman,

is enrolled in a Party school. She becomes infatuated with the

group leader and is seduced by him. This is a delicate,

embivalent work which expresses the confusion, both political

and emotional, of the period it depicts.

Confidence, 1979, directed by Istvlln Szab6, is a love

story mixed with suspense. In Nazi-occupied Budapest a

woman learns that her husband is being hunted by the

Germans. To prevent her from falling into the hands of the

Nazis, the resistance gives her a new identity as the wife of

another fugitive. Posing as husband and wife the couple lives

in constant fear of discovery. In this paranoid environment

27

they fall in love and experience the heights of passion because

of their conviction that every sexual encounter could be their

last.

Diary for my Childrerr, 1984, was directed by Marta

MEszaros and is, to a significant extent, autobiographical. It

combines adolescent reminiscences with historical breadth as

seen through the eyes of an orphaned teen-age girl who

comes to Budapest, in the era of post-war repression, to live

with her aunt, a dedicated Party functionary. The film is

considered to be the hardest hitting depiction of Stalinist ter-

ror to come out of Hungary.

Yugoslav Films:

Three, 1966, was directed by Aleksandar Petrovii:,

considered to be the founder of modern Yugoslav cinema,

who broke the restraints of Realism" and adopted a

modernist style comparable to his contemporary French and

Italian filmmakers. The film was nominated for an Academy

Award. It combines three distinct, but yet related, episodes

in the period of German occupation.

lmwunce Unprotected, 1968, was directed oy Du'!an

Makavejev. It is a semi- documentary which is highly innova-

tive in style and composition. It mixes footage from an

original film with the same title, which was secretly made

during the German occupation, with new materials including

interviews with surviving participants.

The Fragrance of Wild Flowers, 1978, directed by

Srdjan won the International Critics Award at the

Cannes Film Festival. It is a mixture of lyricism and slapstick

comedy, murder mystery, Fellini - tike sideshows, and scathing

social satire. The story concerns a well - known actor who

storms out of a dress rehearsal and goes off to seek a simpler

life in a fishing village on the banks of the Danube. His

peace is disturbed when the media invade his sanctuary,

creating a circus- like atmosphere and attracting thousands of

eccentric converts to the life."

Petria's Wreath, 1980, was also directed by Karanovic.

It is the chronicle of a woman's life across three decades of

mid-century history and is depicted with the artful and

haunting simplicity of the hand-tinted family photographs

which constitute the leitmotif of the film. Petria' s life

encompasses romance, brutality, pettiness, and superstition,

with history always unfolding in the background.

Special Treatme11t, 1980, is an outrageous comedy with

subtle allegory, directed by Goran Paskaljevic. The plot cen-

ters around the head of an alcohol abuse clinic who attempts

to cure his patients with a regimen of apples, Wagner, exer-

28

cise, and psychodrama. Selecting a inotley crew from his

prize pupils, he sets off on a theatrical tour to teach the evils

of drink to the contentedly alcohol-drenched citizenry.

All of the films are in color with t he exception of

ldenli/icalion Marks: None, Walkover, Diary for My Children,

and Three, which are in black and white.

Most of these films are available for rental from New

Yorker Films, 16 West 61st Street, New York, N.Y. 10023,

who will send a catalog upon request. Much of this article is

based on printed materials furnished by them.

29

ANDREI TARKOVSKY 1932-1986

Son of the Russian poet Arseni Tarkovsky, Andrei

Tarkovsky grew up in the artistic milieu of the Soviet writers

colony at Peredelkino. He attended music school and studied

painting before entering the State Institute for Cinema in 1956,

from which he graduated in 1960. Before his death on December

26, 1986, Tarkovsky completed eight films:

The Steamroller and the Violin, 1960. Made a5

graduation requirement for the State lnstitutJ

for Cinema. In Russian.

My Name is Ivan, 1962. In Russian.

Solaris, 1972. Based on Stanislaw Lem's scienc(

fiction novel. In Russian.

Andrei Rublev, 1965. Based on the life of the Rus

sian icon painter. In Russian.

The Mirror, 1975. Based on the filmmaker's ow

life. In Russian.

Stalker, 1979. In Russian

Nostalghia, 1983. Filmed in and around the V ig

noni baths in a fourteenth-century Tuscrq

village. Reviewed by Leo Hecht in SEEDTI

6 #3 (December 1986): 32-36. In Russian an1

Italian.

The Sacrifice, 1986. Filmed in Sweden anc

photographed by Sven Nykvist, lngmar Berg

man's cinematographer. In Swedish.

Tarkovsky's films are poetic and painterly, frequent)

citing and alluding to works by the old masters. Of Tarkovsky

Bergman has said, "He is for me the greatest, the one wh

invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it capture

life as a reflection, life as a dream. " A retrospective o

Tarkovsky's eight films, organized by Anna Lawton, professor o

Russian liter::ture and film at Purdue University, was presented 3

the National Gallery of Art in Washington between November I

and December 27. This obituary is adapted frorn the Filr

Calendar of the National Gallery, Autumn, 1987.

30

KIERKEGAARDIAN MOTIFS IN TARKOVSKY'S

THE SACRIFICE

by Peter G. Christensen

Various artistic contexts have been considered for

Andrei Tarkovsky's seventh and final feature film, The

Sacrifice (1986). Some of these are obvious ones, as they :tre

invoked by the film itself: Leonardo, Bach, Nietzsche,

Shakespeare, and Dostoevsky. Critics have suggested others,

such as Bergman (Shame), Bunuel (The Exterminating Angel),

and Chekhov (Uncle Vanya). However, possibly the most

relevant reference, Kierkegaard's essay Fear and Trembling

( 1843 ), has been overlooked. Not only does it provide a con-

text in which Alexander's strange "sacrifice" can be under-

stood, but it helps mediate between interpretations of the film

which ~ i w Alexander's actions either exclusively as holy or

pathological. It is not my contention that Tarkovsky has

Alexander serve as an unequivocal illustration of the "knight

of faith," but rather that a dramatic situation is created which

is illuminated by Kierkegaard's famous spiritual meditation.

Tarkovsky forces the leap of faith, a form of intense religious

individualism, into a world marked by both the possibility of

repeated but generally undiscovered supernatural events (the

subjects of Otto the postman's investigations) and the per-

formance of religious ritual (as represented by the watering of

the leafless tree).

The most interesting comments on The Sacrifice have

been offered by Pascal Bonitzer in "L'Idee principale"

1

in

Cahiers du Ciilema and Peter Green in "Apocalypse and

Sacrifice"

2

in Sight and Sound. A short, but interesting inter-

view with Tarkovsky3 about the film can be found in Positif,

and some material in his booklength essay Sculpting in Time

4

is also relevant.

Bonitzer argues that The Sacrifice is a metaphysical

and religious apology. The supernatural can only spring

"from the prism of a decomposing reality, through a sick

spirit for example [translation mine];" it is "by necessity secret

and uncertain" here (I 3). Bonitzer points out that if

Tarkovsky had i ndicated without ambiguity that a nuclear

holocaust had been avoided through Alexander's prayer and in

the manner suggested by Otto (the encounter with Maria, the

"witch"), the film's message would risk falling into the

ridiculous.

Further, Alexander's actions would lose all tragic

resonance. For if such deeds were required to save the world

from total devastation who would act otherwise? What real

choice would there be? On the other hand, if everything (the

nuclear attack, the night spent with Maria) turns out to be a

31

dream, then Alexander's burning of the house, his retreat into

silence, and his loss of his family would become the actions

of a mad academic whose incarceration would come as no

surprise. In the second, pathological gesture, there is no

sacrifce either. Sacrifice can only emerge between these two

poles.

Bonitzer's position is very well taken. However, it is

implic i tly challenged by Peter Green, who asks how

Alexander's faith can be evidenced in a world obeying the

natural laws of, everyday life. He writes that the "inevitable

holocaust is averted by the seemingly simple device of turning

the catastrophe into a dream, from which Alexander now

awakes" (118).

Green, unlike Bonitzer, chooses an explanation with

recourse to dream partially because "direct intervention by

God would invalidate the very rule [of explicable events) the

film has established" ( 118). For him, God does not step in as

He did when he stopped Abraham from taking the life of his

son Isaac. Green does not ask if Otto's investigations prepare

us to accept a world of the supernatural. The postman has

already mentioned the woman whose son, a soldier, appeared

to her in a photograph over twenty years after he was killed.

Perhaps Otto's name should remind us of Rudolf Otto's

famous book on religious experience, The Holy ( 1917), which

examines the feeling of terror before the sacred. In Green's

schema for Alexander not to act on his decision to lose his

family would be to "return to the prevarication he abhors"

( 118).

Bonitzer feels that The Sacrifice works because it in

effect inscribes itself in the world of the fantastic (as

described by Todorov), where the bizarre events can be

explained either by dream or by divine intervention. The

film's extraordinary use of color, sepia, and black and white,

along with the unusual editing patterns, helps to maintain the

action in an ambiguous sphere. If the situation is ambiguous,

Tarkovsky avoids giving tragic connotations to Alexander's

actions. Green, however, opts for the dream, and in so

doing, hopes to find in Alexander's choice a tragic dimension,

which Bonitzer can only read as madness.

Had Green turned his mention of Abraham and Isaac

to Kierkegaard's Fear and Trembling, he would have found

several ideas to help us in our analysis of the film: I) the

knight of faith, who can never be a tragic hero; 2) the silence

surrounding the knight of faith; and 3) the inability of the

out!'ide observer to distinguish among another person's acts

which may represent faith, wrongdoing, or madness.

Although there is no direct reference to Kierkegaard

anywhere in the film, we should note that Shakespeare's

32

Richard Ill is mentioned in both contexts. In the film's first

post-credit scene, Alexander receives a birthday greeting from

a friend who once acted on stage with him, "Mighty King

Richard greets good Prince Myshkin." Alexander later

explains to his family that he gave up acting because he could

no longer cope with assuming a false identity, even if his

profession made it an absolute necessity. Whereas the

reference to The Idiot is further developed when the family

remembers a scene in the novel involving the breaking of a

pitcher, the allusion to Richard Ill is more puzzling. Here

K ierkegaard's characterization of the hunchbacked king as

tragic hero is illuminating:

That horrible demon, the most demoniacal figure

Shakespeare has depicted and depicted incomparably,

the Duke of Gloucester (afterwards to become Richard

111)--what made him a demon? Evidently the fact

that he could not bear the pity he had been subjected

to since childhood. His monologue in the first act of

Richard Ill is worth more than all the moral systems

~ h i h have no inkling of the terrors of existence or of

the explanation .of them.5

For K ierkegaard, Shakespeare's play invokes an existential

terror that we commonly associate with Dostoevsky. Initially,

Alexander seems more like the ineffectual, gentle Myshkin,

but as his later destruction of the house

shows, he is capable of going through with violent actions.

In another reference, K ierkegaard presents Richard as

a t ragic hero in conflict with a world which has presented all

its ethical arguments against his acts.

[The tragic hero] can be sure that everything that can

be said against him has been said, unsparingly,

mercilessly--and to strive against the whole world is a

comfort, to strive with oneself is dreadful . . .. The

tragic hero does not know the terrible responsibility of

solitude. (123)

Even if Tarkovsky does not come to Richard Ill

through Kierkegaard, it does not make a comparison unfruit-

ful. The Kierkegaardian categories can still be used to make

sense of the film. First, we should note that the tragic hero is

the p<'rson in distress who weighs society's values of good and

evil against each other. He moves in a world of ethics which

is completely foreign to the knight of faith. Ethics represents

an agreed-upon intermediary world of principles of behavior,

no matter how abstract, and acting on ethical principles is

33

very different from making the leap of faith by which a per-

son lives in direct relationship with God. According to

K ierkegaard:

The genuine tragic hero sacrifices himself and all

that is his for the universal, his deed and every emo-

tion with him belong to the universal , he is revealed,

and in this self -revelation he is the beloved son of

ethics. This does not fit the case of Abraham: he

does nothing for the universal, and he is concealed.

Now we reach the paradox. Either the individual

as the individual is able to stand in an ahsolute rela-

tion to the absolute (and then the ethical is not the

highest)/or Abraham is lost--he is neither a tragic

hero, nor an aesthetic hero. (I 22)

When K ierkegaard asks whether there is a teleological suspen-

sion of the ethical, he answers yes. For him, "faith is this

paradox, that the particular is higher than the universal"(65).

For if the ethical is the highest good, then Abraham's resolu-

tion to heed God and slay Isaac can only be murder.

In The Sacrifice, Alexander commits two actions

which cannot be easily regarded as ethical. He sleeps with

Maria, the Icelandic servant, although he is married to

Adelaide; and he destroys the family home. It is not the

realm of the ethical to sleep with Maria to save the world.

This deed can only be understood as a summons by God.

Otto tells him to do this, and thus, unlike in the example of

A braham, there is a second person involved who has also left

the ethical. If the filmed events are "real," t hen the encounter

with Maria saves the world, and the burning of the home

saves Alexander' s soul. Both event's appear absurd, a notion

which Kierkegaard links with individual faith:

(A braham) acts by virtue of the absurd, for it is

precisely absurd that he as the particular is higher

than the universal. This paradox cannot be mediated;

for as soon as he begins to do this he has to admit that

he was in temptation (Anfechtung), and if such were

the case, he never gets to the point of sacrificing

Isaac, or, if he has sacrificed Isaac, he must turn back

repentantly to the universal. By virtue of the absurd,

he gets Isaac again. Abraham is, therefore, at no

instant a tragic hero but something quite different,

either a murderer or a believer. (67)

Tarkovsky minimizes the elements of this form of

temptation in the treatment of Alexander. After Otto tells

34

him that he must go to Maria, he is not presented openly

debating with himself, nor does he have any interactions with

other characters. In Maria's living room, he plays an organ

prelude and recounts the long story about how he had

unintentionally destroyed his mother's garden by trying to

change its natural state into an ordered one. When he puts

Yiktor's gun to his head, while Maria is standing at the table,

this may look like temptation to avoid the unethical deed, but

it is more likely a gesture of despair, a belief that the mission

can only be in vain. At this point Maria comes to him, and