Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Life Is Fair

Hochgeladen von

bipinbediOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Life Is Fair

Hochgeladen von

bipinbediCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Life is Fair

The Law of Cause and Effect

by Brian Hines

[Revised 8/13/98]

1

Be not deceived;

God is not mocked:

for whatsoever a man soweth,

that shall he also reap.

Galatians 6:7

Cartoon credits:

!a"e #$, from Einstein Simplified by %idney Harris. &opyri"ht 1'(' by %idney

Harris. By permission of %idney Harris.

!a"e $$, from the Doctor Fun series p)blished on the *nternet. By permission of

+avid ,arley.

Story credits:

-.m * Bl)e/0 from Living b t!e "ord# Selected "ritings 19$3%8$, copyri"ht 1'(6

by .lice 1alker, reprinted by permission of Harco)rt Brace 2 &ompany and +avid

Hi"ham .ssociates 3imited.

-4he %la)"hterer0 translated by 5irra Ginsb)r" from &!e 'ollected Stories of (s))c

*)s!evis Singer by *saac Bashevis %in"er. &opyri"ht 1'( by *saac Bashevis %in"er.

6eprinted by permission of ,arrar, %tra)s 2 Giro)7, *nc. and 8onathan &ape, 3imited.

-. 5other9s 4ale0 from &!e 'ollected S!ort +rose of ,)mes -gee, copyri"ht 1'6'

by 4he 8ames ."ee 4r)st. .ttempts to contact the copyri"ht holder were )ns)ccessf)l,

and the Ho)"hton 5ifflin &ompany book in which the story appeared is o)t:of:print. 4he

p)blisher, 6adha %oami %atsan" Beas, wo)ld welcome any information concernin" the

stat)s of 4he 8ames ."ee 4r)st, and re"rets not bein" able to obtain permission to reprint.

#

Table of Contents

!reface $

;7pandin" <)r =iew of 3ife 7

.nswerin" 3ife9s Bi" >)estions 17

.ll 3ife *s <)r ,amily #'

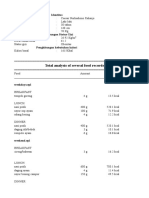

=e"etarianism, 5eat:;atin", and %)fferin" ?$

;ssays 71

4he @at)re of 6i"ht and 1ron" 7

Aarma &larifiedB4he ,airness 5achine (

- Reverence for -ll Life# &!ree S!ort Stories 1C7

-.m * Bl)e/,0 by .lice 1alker 1C'

-. 5other9s 4ale,0 by 8ames ."ee 11

-4he %la)"hterer,0 by *saac Bashevis %in"er 1?

%)""estions for ,)rther 6eadin" 1#$

;ndnotes 1#7

.cknowled"ements 1$C

$

Preface

*t is a si"nificant feat)re of recent times that we are enco)ra"ed to probe, D)estion,

and think abo)t every aspect of life. 1e may remind o)rselves this was not always the

case. ,or tho)sands of years this activity was the prero"ative of philosophers and

theolo"iansBthe people were e7pected to comply with the opinions and beliefs of their

time and place. *n the last few h)ndred years the philosophers and cler"y have been

"rad)ally s)pplanted by the scientist.

@ow, in o)r present times, the ideal of )niversal ed)cation enco)ra"es each one of )s

to establish o)r answers for o)rselves. Anowled"e, in principle, is eD)ally available to all,

and nowhere is this ill)strated more clearly than in the )nre")lated flow of information

thro)"h the worldwide web.

*f a ")ideline for life is to be meanin"f)l today, clearly it has to withstand the scr)tiny

of lo"ic and reason. *t also has to be s)fficiently far:reachin" and )niversal so as to remain

valid in the conte7t of o)r technolo"ical and m)lti:c)lt)ral societies. 1e are challen"ed by

the different o)tlooks and beliefs of o)r friends and nei"hbors to widen o)r perspective

and find )niversal principles that )nite )s on life9s common "ro)nd.

4his book asks the reader to open his or her mind to consider what may be for some a

new perspectiveBa )niversal, spirit)al view of life that sits comfortably with a scientific

approach. *t is a perspective that helps to resolve some of the "reat contradictions we all

face. 4he book9s messa"e, that life is fair and we only ever "et what we deserve, will not

make sense, however, if we look at life thro)"h a narrow window. 4he a)thor therefore

asks )s to step back and perceive life more broadly. He presents to )s the way mystics see

life and shows )s how their vision complements and enriches a scientific world view.

By -mystics,0 he means those people who, thro)"ho)t history and in all parts of the

world, have spoken of a level of spirit that is common to the "reat reli"io)s traditions.

4hey are people whoBthro)"h direct perception or ill)mination, not thinkin" or analysis

Bhave e7perienced the formless lovin" power in which all life has its so)rce. B)ildin" on

o)r reason and lo"ic, if we take their vision and )nderstandin" as o)r framework, we find

that all life is endowed with meanin" and p)rpose.

-3ife,0 the book says, -does not make complete sense to )s beca)se we have no sense

of the completeness of life.0

5ystics describe reality in terms of two f)ndamental principles: love, the very st)ff of

e7istence, the positive power that ener"iEes everythin"; and .ustice, the law of ca)se and

effect that weaves and dyes the comple7 patterns of creation and ens)res that its fabric

never wears away.

4he foc)s of this book is the principle of F)sticeBand most importantly, that correct

)nderstandin" and application of the workin"s of this principle are essential if we are to

e7perience the divine potential of the more f)ndamental and all:embracin" principle of

love.

Gsin" metaphors drawn from o)r daily e7perience, the a)thor describes how the law

of action and reaction, of ca)se and effect, reaches m)ch f)rther than we commonly

)nderstand. .s he presents )s with a vision of the vastness of life and conveys how the

principle of F)stice operates at s)btle spirit)al levels of which we are not normally aware,

he leads )s to )nderstand why thin"s happen in the way they do. 3ookin" at life from this

perspective, we find that practical D)estions of ri"ht and wron" can be resolved, and we

have the basis for a lo"ical and )niversal moral code.

*t is simple: positive actions prod)ce positive res)lts; ne"ative actions prod)ce

?

ne"ative res)lts; no action "oes )nanswered; and the principle of perfect F)stice links

everyone and everythin" thro)"h all time and space. .t the individ)al level, once we

)nderstand that we only "et back from life whatever we "ive, it makes sense to act

positively if we want a positive, happy life.

%ince killin" is an action that always carries its conseD)ence of pain and s)fferin", a

life of non:violenceBincl)din" not eatin" animalsBis a nat)ral o)tcome of this

)nderstandin". =e"etarianism is also the preferred choice for many who simply choose to

live in harmony with what they sense to be the essentially lovin", or positive, nat)re of

creation. &ompassion, the active concern for the well:bein" of all life, is the crossroads

where we can lift o)r h)man lot to a hi"her e7perience of bein". *t is o)r opport)nity to

"ive ear to the divine instinct within each one of )s and, thro)"h the way we live,

transm)te the principle of balance and perfect F)stice that r)les the world into the

e7perience of love.

Before askin" the reader to consider what may be for many a new perspective, the

a)thor D)estions some ass)mptions that )nderlie o)r common perceptions of everyday

life. @e7t he sets abo)t providin" a more comprehensive pict)re of life, incl)din" those

aspects which we cannot readily see. 1ith this fo)ndation he then t)rns to the implications

of divine F)stice for everyday life, and disc)sses the importance of caref)lly choosin" what

we eat to s)stain o)rselves. 6esearch on the health effects of meat:eatin" is also presented

to s)pport the book9s ar")ments relatin" to ve"etarianism.

.lso incl)ded are two essays which e7pand )pon the central themes of Life is F)ir:

morality and the law of karma, or divine F)stice. 4he first essay e7amines the nat)re of

ri"ht and wron", and how a -moral compass0 wo)ld work if s)ch a device act)ally

e7isted. 4he essay on karmaB-4he ,airness 5achine0Bwill be of partic)lar interest to

those who want to know !o/ the moral law of F)stice ens)res that we always reap the

conseD)ences of o)r actions.

4he %ociety is privile"ed to incl)de at the end of the book three short stories by

distin")ished a)thors: the !)litEer priEe winners .lice 1alker and 8ames ."ee, and a

winner of the @obel priEe for literat)re, *saac Bashevis %in"er. 1ith strikin" literary

accomplishment, each a)thor conveys a messa"e abo)t the oneness of life. *t is a fact that

by whatever meas)res we )se to define o)rselvesBby species, c)lt)re, "ender, lifestyle, or

convictionsBwe also separate o)rselves from all others. 1e remove o)rselves from those

we think are not like )s. *f they s)ffer, it means nothin" to )s for they are somethin" else,

beyond the reach of o)r compassion. 1e are who we are. 4hey are who they are.

1hy do we s)ffer when someone we love is s)fferin"/ Beca)se we feel connected to

them. 4hese stories are incl)ded in the book beca)se each one takes )s across a barrier we

mi"ht not normally cross. 4hey draw )s into the heart of the other9s e7perience and raise

the D)estion: are the fears, the conf)sion, the Foy, and the love felt by others so different

from o)r own feelin"s/

*n the conviction that a respect for all life marks an important step on the road to self:

knowled"e, it is with "reat pleas)re that the %ociety presents this clear and modern

e7planation of how the moral law of F)stice works.

%ewa %in"h

%ecretary

6adha %oami %atsan" Beas ,ebr)ary 1''(

Expanding Our View of Life

>)estion: 0)ster1 t!e most !elpful t!ing ( !)ve received from our lips is /!en ou s)id1

6

23ou get onl /!)t ou deserve45

.nswer: "!)t ( me)n b 2/e get onl /!)t /e deserve5 is t!)t /!)tever /e !)ve done

in t!e p)st1 /e !)ve so/n cert)in seeds to deserve /!)t /e )re getting no/4 "e re)p

/!)t /e !)ve so/n in t!e p)st1 )nd no/ /e deserve it4 &!erefore1 /e s!ould )l/)s do

t!ose )ctions of /!ic! /e /)nt to re)p t!e desired results4

5aster &haran %in"h, &!e 0)ster -ns/ers

1

')lvin )nd 6obbes 1atterson. 6eprinted with permission of Gniversal !ress %yndicate. .ll ri"hts reserved.

3ife is fair. 1e "et what we deserve.

4o many people, these are o)tra"eo)s statements. How co)ld life possibly be fair

when there are so many obvio)s inF)stices/ Babies bein" born blind. 5)rderers escapin"

p)nishment. @efario)s swindlers prosperin" at the e7pense of innocent victims.

Hes, it is indeed diffic)lt to ima"ine that life is fair. B)t consider, for a moment, that

it is tr)e. *s it possible that life appears )nfair only beca)se we are not seein" the

completeness of life/ &o)ld a limited view of e7istence be the reason why we fail to see

how, and why, every livin" bein" "ets precisely what it deservesBno more, and no less/

*f we came to believe that the correct answer to these D)estions is yes, then every

aspect of o)r life wo)ld take on new si"nificance. 1e co)ld no lon"er blame fickle fate or

happenstance when bad thin"s occ)r to )s. 1e also wo)ld find it easier not to blame

others when life isn9t to o)r likin". 1e wo)ld take a fresh look at everythin" we do and

think, with the knowled"e that whatever we send o)t into the world, both the "ood and

the bad, one day will ret)rn to )s in like meas)re.

Life is F)ir says this is e7actly how life works. B)t if we are to )nderstand how F)stice

operates in the world, we m)st first st)dy life9s bi" pict)re. 1e cannot e7amine life only

from the point of view of the material sciences. 1e m)st also look at life from a spirit)al

perspective. 4hen we will learn that as h)man bein"s we are in a )niD)e position. 3ike no

other livin" bein"s, we have the capacity to )nderstand the s)btle laws that "overn the

world. 1ith this knowled"e, we can then make choices that will lead )s toward the

harmony and happiness every person seeks in one way or another.

8)st as the material sciences provide e7planations for many of the thin"s that happen

to )s, so does the spirit)al perspective e7plain why we s)ffer or why we are happy. *t

shows )s that there are "ood reasons for everythin" that happens to )s. 1e "et what we

deserve. .nd this way of )nderstandin" pins the responsibility for what we do, and what

happens to )s, sD)arely )pon o)rselves. .ny distress we ca)se to othersBwhether h)man

or animalBis re"istered in the atmosphere of o)r conscio)sness, where it ret)rns to )s in

the form of storms of pain and misery. *f we "et blown off co)rse on the way to the 3and

of Happiness, that sD)all is of o)r own makin".

<nce we come to accept that the law of ca)se and effect "overns all life, both physical

7

and metaphysical, we see that every tho)"ht and action ass)mes a moral dimension. .ll

that we do and think leaves its mark. . lon" Fo)rney is made of many short steps. 4he

overall co)rse of o)r life is determined by decisions made every instant. 5oment by

moment, an )nceasin" flow of mental and physical action carves the channels thro)"h

which the ship of o)r self sails in the f)t)re. <)r loftiest "oals and most down:to:earth

activities are seamlessly linked.

*n a similar fashion, readers will find an intimate blend of philosophical iss)es and

practical concerns in Life is F)ir. *n almost the same breath there may be talk abo)t both

carrots and the cosmos, abo)t the nitty:"ritty reality of the food we keep in o)r

refri"erator and the ethereal nat)re of spirit)al reality. %till, )nderlyin" the words on all

the pa"es is one basic ass)mption: whatever we do in life, we )s)ally do beca)se we think

it will make )sBor those aro)nd )sBhappy.

*f this is tr)e, and it seems obvio)s that it is, then it is important to know what

prod)ces happiness or peace of mind. Gnless this is known with certainty, o)r efforts to

move in that direction )nknowin"ly may be leadin" )s the wron" way.

Desere !ore "appiness# $eco!e !ore desering%

%cience is be"innin" to come )p with some intri")in" partial answers to the all:

important D)estion of why some people are happier than others. %t)dies of sets of

identical twins Isome of whom were raised to"ether, and some apartJ have fo)nd that one:

half or more of o)r tendency to be happy is fi7ed at birth. 4hat is, at least half of the

happiness we e7perience as an ad)lt apparently flows from "enetic infl)ences, and the rest

from other ca)ses.

8.B. Handelsman 1''6 from 4he @ew Horker &ollection. .ll ri"hts reserved.

*t is a soberin" tho)"ht to realiEe that factors beyond o)r control prod)ce so m)ch of

o)r happiness Ior sadnessJ. *9m born. KapL ,ifty percent of my tendency for f)t)re Foy and

(

sorrow is determined before * even take my first breath. &an this be fair/ <nly if o)r life is

part of a contin))m of e7istence that be"an lon" before we were born and will contin)e

lon" after we dieBif not for eternity.

4his immediately moves )s into a broader view of life than o)r everyday e7perience

)s)ally is able to provide. 1e need a perspective that encompasses far more than the

min)te slice of e7istence with which most of )s c)rrently are familiar.

T"ere is !ore to life t"an !eets t"e eye

*f yo) are one of the many who believe there is no evidence for any sort of reality

beyond the physical world, it may be helpf)l to remember that even to )nderstand material

reality we have to e7pand o)r horiEons. ;ven matter has vario)s levels which cannot

readily be known. 4he pa"e on which these words are printed appears to be solid when

viewed with the h)man eye. +elvin" deeper with the aid of a powerf)l microscope, this

piece of paper wo)ld take on a completely different appearance. .nd at the most basic

s)b:atomic level, science tells )s that the -matter0 of this pa"e consists of ethereal waves

of p)lsatin" ener"y.

*f we challen"e the e7istence of the spirit)al world beca)se the tools we )se to

)nderstand material reality do not demonstrate it to )s, we may be reactin" like a person

who denies the s)b:atomic reality of this pa"e beca)se he cannot see it thro)"h a

ma"nifyin" "lass.

Life is F)ir, therefore, asks yo) to temporarily s)spend some of yo)r ass)mptions

abo)t reality. ;ntertain the possibility that there is more to life than meets the eye, and

that this -more0 can be known by cond)ctin" the proper e7periments. ,or the most part,

we see o)r life )nfold, b)t fail to realiEe what prod)ces the circ)mstances that s)rro)nd

)s: o)r health, o)r wealth, o)r loves and hates, o)r Foys and sorrows. *f we apply the

proven method of scientific investi"ationBri"oro)s testin" of hypothesiEed tr)thsBto

spirit)al e7istence, perhaps we can )nderstand life in a more holistic and meanin"f)l way.

4he spirit)al perspective )nderlyin" these ar")ments arises from the e7perience of

)nity at the heart of life. 4he reader is asked to consider that the separations we

commonly makeBs)ch as between mind and matter, people and animals, heaven and

earth, God and the creationBlimit o)r )nderstandin" of a far:reachin" moral law.

4he e7perience of )nity challen"es o)r )s)al pres)mption that a bi" difference e7ists

between the world -o)t there0 and the world -in here0; that is, between rocks, clo)ds,

trees, animals, and all the rest of the physical world which we see, and hear, and to)ch

with o)r senses, and the seemin"ly vastly different inner reality of o)r tho)"hts, fears,

Foys, loves, and desires.

&oing beyond reflections of reflections

*f the cosmos is indeed a whole, yo) mi"ht well ask, -1hy does everythin" appear so

fract)red70 !erhaps this simple e7periment provides the be"innin" of an answer.

%tand in front of a lar"e mirror and hold a small mirror in yo)r hand, the "lass facin"

toward yo)r reflection. Ho) will see a hand holdin" a mirror, which contains an ima"e of

a hand holdin" a mirror, which contains an ima"e of a hand holdin" a mirror, and so on,

apparently witho)t end. .maEin"L <ne hand and one mirror prod)ced all of these myriad

reflections. .ppearances certainly can deceive.

%imilarly, we can think abo)t the world o)tsideBor insideBof o)rselves, and then

think abo)t those tho)"hts, and then think abo)t the tho)"hts abo)t o)r tho)"hts. *f we

keep on in this fashion, we may even become a "reat philosopher, or a theolo"ian, or a

madman. Het no matter how lon" and how intensely we may reflect )pon ima"es of

mirrors within mirrors, or ponder tho)"hts abo)t thinkin", the simple reality of what lies

'

beneath appearances will el)de )s.

1e need a hi"her perspective.

Ho) can s)pply that broader vision yo)rself in the case of the mirror within the mirror,

beca)se yo) know that yo)9re the one prod)cin" the ill)sion. 1hen yo) lower yo)r hand,

the ima"es inside the ima"es disappear. Ho)9re left with a sin"le reality. However, when

thinkin" abo)t tho)"hts, or feelin" feelin"s, the sit)ation is more complicated. 1here is

the vanta"e point on which we can stand and clearly see o)r own self/

Here9s the problem: How do * fi")re o)t what life is, and therefore how * sho)ld live

Bwhich incl)des how * behave toward other forms of lifeBwhen * can9t even fi")re o)t

what or who is doin" the fi")rin"/ 4his con)ndr)m drives many to rely on f)it! as the

answer to life9s bi""est D)estions.

Don't "ae too !uc" fait" in fait"

.ll in all, faith is an over:rated virt)e. .t its best, faith is a promissory note for tr)th

Ban *.<.G. to be "rasped )ntil the hard coin of certainty is handed over. .t its worst,

faith "ives its holder the ill)sion of possessin" somethin" s)bstantial. . mira"e is

mistaken for reality. %ince different people often have faith in completely contradictory

beliefs, clearly some faith is well:fo)nded, and some faith is "ro)ndless.

,aith is like a si"npost that can be made to point either way at a fork in the road. Ho)

can have complete faith that yo) are travellin" in the ri"ht direction, b)t if it t)rns o)t that

yo)9re on the wron" road yo)9ll never "et to yo)r destination. .nyone who has become

lost while drivin" a car knows this.

4r)th, then, has to lie down one path or the other. *f one accepts that there is an

obFective reality independent of any individ)al9s perception of that realityBand both

material science and the spirit)al world view tell )s that there isBthen it seems impossible

that completely opposed e7planations of e7istence are both ri"ht.

%o rather than relyin" on a si"npost that swin"s in one direction, then the other, a

detailed map of the s)rro)ndin" area wo)ld be a better ")ide. Gsin" the map to e7plore

the territory yo)rself clearly wo)ld be best of all, since then yo) wo)ld have no do)bt

abo)t the correct ro)te. %)ch is the method of science, movin" from faith to facts.

(eat"er always is fair

4he scientific method has had tremendo)s s)ccess in layin" bare the mysteries of the

world -o)t there.0 1e enFoy the advances of science every time we t)rn on a microwave

oven, )se a comp)ter, or talk by phone to a friend halfway aro)nd the world. %cience

accomplishes so m)ch beca)se it ass)mes that life is fair. 4he world makes sense. @at)re

is not arbitrary. 4here are laws waitin" to be discovered thro)"h proper investi"ation, and

then )sed to o)r advanta"e.

&onsider how o)r view of the weather has chan"ed d)rin" the past few decades. .s a

child, many readers will remember lookin" at a barometer to tell whether or not a storm

was comin". 1ith a chan"e in air press)re, the pointer wo)ld move closer to either the

-fair0 or -stormy0 marks on the dial. Hes, there were weather forecasts on radio and

television, b)t they seemed barely more acc)rate than cons)ltin" the primitive barometer

han"in" in the kitchen.

@ow we are acc)stomed to seein" remarkable satellite photo"raphs on the ni"htly

news. *n the western Gnited %tates, for instance, the weather man or woman can point to

a storm system developin" many h)ndreds of miles away in the G)lf of .laska, overlay a

dia"ram of the prevailin" hi"h altit)de air c)rrents, and tell viewers that the ne7t few days

are "oin" to be cold and rainy. .nd )s)ally he or she is ri"ht.

4he same applies at the other end of the co)ntry in ,lorida. 3ate s)mmer and early

1C

fall is h)rricane season. %atellites are able to detect tropical storms brewin" in the warm

waters of the .tlantic, and track them as they occasionally "row to h)rricane stren"th. .

h)rricane9s path can be predicted D)ite acc)rately. 3ives and property are saved beca)se

of the advance warnin" provided by the weather service.

H)rricanes, alon" with the rest of the weather, have nat)ral ca)ses. 5eteorolo"ists

know how a h)rricane develops and why it travels in a certain direction. 4he stren"th of

its winds and the path it takes are determined by impersonal forces that can be known

precisely in theory, if not yet in act)ality.

.ll of )s know that weather doesn9t F)st happen. %)nny warm days and cold bl)stery

ni"hts each have their roots in the laws of nat)re. 4hese laws are absol)tely fair since

everywhere in the )niverse, so far as scientists know, they operate in e7actly the same

way. 4he weather in .merica is ca)sed by the very same forces as the weather in .sia.

-<)tside0 weather, then, clearly is fair. @ot that fair days always "reet )s when we

rise each mornin", b)t in the sense that climate is prod)ced by obFective laws of nat)re

which work the same way in every part of the world.

)ow's t"e weat"er inside today#

,or most people, the inside weather seems to be a different matter entirely. -*nside

weather,0 yo) may ask, -what does that mean/0 4hese are the climatic conditions /it!in

o)rselves: the s)nshine of optimism and the clo)ds of "loom, the fo" of depression and

the clear sky of Foy, the bl)stery winds of an"er and the calm air of serenity, the li"htnin"

bolts of pain and the warm winds of pleas)re.

1ho can say that they haven9t had tho)"hts like these at one time or another: -* didn9t

deserve this.0 -*9ve been doin" everythin" ri"ht; how co)ld this happen/0 -<ther people

"et all the l)ck.0 <r, -4hin"s are "oin" too "ood for me; somethin" bad is bo)nd to

happen.0 Behind each of these tho)"hts is an ass)mption that life is some kind of dice

"ame, and probably an )nfair one as well.

@ot only does chance seem to determine how we feel and what happens to )s, b)t

some people appear to play with loaded dice. 4hey seem to "et m)ch more o)t of life

than they deserve, while others "et m)ch less. *f we applied s)ch thinkin" to the weather,

it wo)ld be akin to sayin" that the %ahara desert is bein" cheated o)t of moist)re by the

BraEilian rain forest. <r that an earthD)ake which hits 8apan happened by chance.

4hose ideas wo)ld be la)"hed at, ri"htf)lly, by climatolo"ists and "eolo"ists. 6ain

patterns and earthD)akes don9t F)st happen, or happen -)nfairly;0 they occ)r for lo"ical

reasons. %o whenever we look )pon the deli"hts and miseries of o)r life as bein" )nF)st

or )ndeserved, it is beca)se we ass)me there are no laws to e7plain them. 1e pres)me

that the way the o)tside world works is D)ite different from what we feel within.

5aybe it is wron" to make s)ch a division between the clearly lawf)l physical world,

and the seemin"ly m)ch more capricio)s mental worldBthe arena in which we feel Foy

and sorrow, love and hatred, contentment and desire, and all the other e7periences that

come with bein" h)man. 1hile the mind certainly operates with more comple7ity than

does matter, perhaps the same basic laws of e7istence )nderlie both. . fit of ra"e may not

be so different from a passin" sD)all.

.s with other s)btle tr)ths, however, this isn9t readily apparent. 6ecall that a reliance

on appearances wo)ld have )s believin" that the s)n "oes aro)nd the earth, as people

ass)med for many millennia. %o it is )nderstandable why many find it diffic)lt to believe

that the internal world of tho)"hts and emotions is as lawf)l and determined as the

e7ternal world of air, water, and minerals. Het almost everyone wo)ld a"ree that like the

weather o)t there, the weather in hereBin o)r conscio)snessBalways is chan"in". @o

one feels the same all the time. ;veryday lan")a"e reflects this fact. *n describin" the

11

patterns of o)r lives, we often so)nd like meteorolo"ists.

-*9ve "ot a black clo)d han"in" over my head,0 )tters a sad person. . man who can9t

conceal his happiness is "reeted with, -1ell, here comes 5r. %)nshine.0 1hen recallin" a

partic)larly movin" event, a person may speak of bein" -flooded with emotion.0 -+id

somebody rain on yo)r parade/0 we ask an acD)aintance who appears letdown.

%till, even tho)"h the words )sed to describe e7ternal and internal weather are similar,

there are clear differences in the reality reflected by those words. *f we don9t like the

weather where we are livin", two choices are open to )s: move to another location, or

chan"e o)r attit)de. &an9t stand the snow/ 5ove to a warm place. 3ove raindrops

fallin" on yo)r head/ 5ove to a rainy place. <r if movin" isn9t an option, we can try to

accept the conditions aro)nd )s rather than complain abo)t them.

C"anging your internal cli!ate

<ne of these two choices is eliminated in the case of the weather inside )s. &learly it is

impossible to move o)tside o)r own conscio)sness. *f we find o)rselves drenched in

despair most of the time, we can9t call )p the 5ental &ontents 5ovin" &ompany and have

o)r mind shipped to a locale where it never rains sadness. !eople have to live with

themselves. *f o)r mind were elsewhere, we obvio)sly wo)ld be somebody else.

%o if movin" isn9t an option, how do we deal with )npleasant climatic conditions

within o)rselves/ 1ell, F)st as with the o)tside weather, it is always possible to try and

accept what is, and not desire to chan"e it. *f we9re happy, we can be content with

happiness. *f we9re sad, we can be content with sadness. B)t it is e7tremely diffic)lt to

attain this state of eD)animity. 6arely, if ever, does anyone accept sorrow and Foy eD)ally.

*t is nat)ral to want to be happy rather than sad, to desire pleas)re over pain, to seek love

rather than hate.

')lvin )nd 6obbes 1atterson. 6eprinted with permission of Gniversal !ress %yndicate. .ll ri"hts reserved.

.ll ri"ht, then. 1e can9t move o)tside o)r own mind, and we can9t accept all that we

find there; that is, we9d like to keep the "ood -weather0Bsensations of contentment,

happiness, pleas)re, and FoyBand "et rid of the opposite sensations of an7iety,

depression, pain, and despair. &learly we have to find a way to chan"e o)r internal

weather. %o the D)estion is whether we can do somethin" which meteorolo"ists cannot:

alter the patterns that prod)ce )ndesirable climatic conditions.

*f there are reasons why somethin" happens, if there is a law "overnin" a partic)lar

sort of activity, then there is a possibility of control. *f life is fair, and we "et what we

deserve, then in principle there is the possibility of becomin" happier by becomin" more

deservin".

4he science of meteorolo"y has made "reat strides in comprehendin" the dynamics of

the earth9s weather, b)t the sciences that try to )nravel the mysteries of h)man nat)re are

1

still in their infancy. 4he weatherman on 4= can acc)rately forecast how hot it will be

tomorrow, b)t no one can tell )s how happy we will be when the s)n rises. 4ho)"h

psycholo"y and medicine have had some s)ccess in treatin" mental and physical diseases,

this is like bein" able to repair the roof of a barn after a hi"h wind has torn it off.

,rom where do the storms of illness that rava"e o)r minds and bodies ori"inate/ How

can we avert these dist)rbances/ &o)ld it be that o)r own actions infl)ence whether or

not o)r conscio)sness enFoys the eD)ivalent of calm s)nny days and peacef)l warm ni"hts/

)eig"ts of !ystic experience

&ameras on weather satellites transmit photo"raphs of earth that enable )s to see

lar"e:scale weather patterns that cannot be discerned from "ro)nd level, or even an

airplane. %imilarly, the teachin"s of the mystics, the spirit)ally e7periencedBor -spirit)al

scientists0Bcomm)nicate to )s their knowled"e of hi"her planes of conscio)sness.

B)t why, we may ask, is it that only mystics e7perience these hi"her planes/ 1hy

aren9t more people aware of them/ 1hat prevents everyone from knowin" the facts of

spirit)ality and perceivin" the depths of reality/ .re there reasons why most people are

i"norant of spirit)al e7istence, F)st as there are reasons why a destr)ctive h)rricane t)rns a

b)ildin" into r)bble/

4here is "eneral a"reement, even amon" scientists, that all the tools of modern science

have failed to penetrate the mysteries of life and conscio)sness. ,rom a spirit)al

perspective one wo)ld say this is beca)se the tools are not s)ited to the Fob. 4he answers

to the riddles life poses, say the spirit)al scientists, lie within life and conscio)sness itself,

not o)tside in dials, co)nters and comp)ters, nor in comple7 mathematical eD)ations that

describe only the smoke of physical reality and not its creative fire.

!)re conscio)sness, says the mystic, is lifeMs creative fire. %pirit, or conscio)sness at its

hi"hest and most refined level, is the basic b)ildin" block of all life, and indeed of all

e7istence. 4his is the )ltimate reality, or -4heory of ;verythin",0 that material science

seeks to discover. .nd the only tool we need to e7perience this tr)th, says the mystic, is

o)r h)man conscio)sness.

How simple. <)r h)man conscio)sness, or -so)l,0 is capable of e7periencin"

)niversal conscio)sness, -spirit.0 B)t simple is not the same as easy. *t "enerally reD)ires

"reat effort to transform o)r weakened, scattered psyche into a powerf)l, foc)sed means

of contactin" the hi"hest reality. Het the str)""le is worthwhile, for if we come to know

o)r essence, the basic b)ildin" block of all life, we know everythin"; havin" o)r tr)e self,

we have everythin".

1e need to become adepts in the science of spirit)ality if we are to find the answers to

lifeMs "reatest D)estions. 1e need to work on o)rselves, o)r inner bein", and not F)st the

world o)tside of )sBwhich )s)ally is o)r main interest, and o)r main concern. 4o be

effective, this tool of h)man conscio)sness has to be in s)perb condition. %o we need to

)nderstand everythin" that affects it for "ood or ill.

Law of cause and effect

<)r conscio)sness is like a wave of ener"y, or life force, that is intimately related to

the vast ener"y field of the creationBa min)te particle of the )nified s)bstance some call

God. *n theory, by f)lly e7periencin" the part we can e7perience the whole. However, in

fact o)r conscio)sness is rendered ineffective by its connections with o)r mind and body,

somewhat as interference that prod)ces lo)d static makes it impossible to clearly hear

m)sic on a radio.

*f we are to receive clear information abo)t the whole of which we are a part, this life

force has to be refined or p)rified )ntil it ret)rns to its ori"inal state. 1e m)st re"ain o)r

1#

ability to -t)ne in0 to the wavelen"th of hi"her spirit)al tr)ths. ,or this, we m)st

)nderstand the laws that "overn life, the most decisive bein" the law of ca)se and effect.

4he o)tcomes of this law keep o)r conscio)sness bo)nd to the cr)dity of mind and matter

and prevent )s from e7periencin" the s)btle reality of spirit.

4he law of ca)se and effectBas yo) sow, so shall yo) reapBwe all accept to some

e7tent in daily life. *f we work hard at o)r Fob, we are likely to "et a raise. *f we eat too

m)ch, and e7ercise too little, we will "ain wei"ht. *f we treat someone kindly, kindness

probably will be ret)rned to )s. *f we drive o)r car too fast on a sharp t)rn, we will r)n

off the road.

Het few of )s have any idea that the same law operates )nremittin"ly and witho)t

e7ception at more s)btle and deeper levels. Anown as the law of karma in several eastern

c)lt)res, this law of spirit)al reality means that all o)r tho)"hts and actions, like seeds of

sweet or bitter crops, are re"istered or -sown0 not F)st in o)r present personality, b)t also

deep in o)r conscio)sness at s)perphysical levels of e7istence. 4hese seeds "enerate

harvests in keepin" with their nat)re. %ometime in the f)t)re we have to reap their nat)ral

fr)its.

5istakenly, we try to e7plain life in terms of physical laws alone. Beca)se o)r

)nderstandin" of spirit)al e7istence is limited, we fail to reco"niEe that what we are

e7periencin" in this lifetime is the harvest from seeds of tho)"hts and actions sown earlier.

Both o)r e7periences and the person doin" the e7periencin"Bthe -*0 that responds when

someone calls yo)r nameBare the res)lt of the spirit)al law of ca)se and effect. 1e fail to

see that the workin"s of this law at the met)physical Ibeyond the physicalJ level infl)ences

o)r conscio)sness at the physical level, where we have the impression life be"ins and ends.

T"e nature of !orality

&onsider this simple D)estion: how do we decide what to do in life/ .fter all, yo)

co)ld be doin" many different thin"s ri"ht now. &ookin" a meal. Goin" for a walk.

4alkin" with friends. %eein" a movie. !attin" a pet. 1hy, indeed, are yo) readin" this

book/ How do we decide what is important, and what is )nimportant/ 1hat actions are

ri"ht and what are wron"/

,or many people in the world the maFor D)estions of life, incl)din" matters of

morality, are decided by their reli"ion. Beca)se they believe in a partic)lar faith, they try

to live by the moral code associated with it. B)t there are as many different moral codes as

there are different reli"ions. How do we choose between them, or how does a non:

reli"io)s person decide what is important or ri"ht/

. person who doesn9t s)bscribe to a partic)lar reli"io)s belief may concl)de that there

is no s)ch thin" as an absol)te standard for determinin" what is ri"ht and wron". 5orality

)nderstandably is considered to be a matter of c)lt)re, of reli"io)s, social or le"al

convention, or dependent on how a person is raised. *n the ;ast, for instance, people

cover their heads as a si"n of respect. *n the 1est, people take off their hats. 5oral codes

even may be seen as a device for e7ercisin" control over others: "overnment over citiEens,

reli"io)s a)thorities over believers, parents over children.

B)t what if the simple law of ca)se and effect is the absol)te standard that holds

constant for every h)man, and indeed all of life/ 1hat if this law "overns the

conscio)sness of every livin" bein" with as m)ch certainty as do the principles of anatomy

and physiolo"y in the bodily sphere/

*f a person c)ts himself with a knifeBwhether he believes in the laws of physiolo"y or

notBdeath certainly will follow if the bleedin" is not stopped. 1hat if the law of karma is

as inviolable as this, and every one of )s has to reap the conseD)ences of each of o)r

tho)"hts and actions/ &o)ld it be that each time s)fferin" is ca)sed, those responsible

1$

m)st one day s)ffer themselves in recompense for the pain and misery they prod)ced/

')lvin )nd 6obbes 1atterson. 6eprinted with permission of Gniversal !ress %yndicate. .ll ri"hts reserved.

%a"es have compared life to a dan"ero)s voya"e across an ocean. 1e are sailin" on

the fra"ile craft of o)r mind and body which sometimes makes headway in the desired

direction, b)t all too often is tossed abo)t aimlessly beyond o)r control. 4he spirit)al law

of ca)se and effect ens)res that it is o)r own ne"ative tho)"hts and actions which ca)se

the bad weather in o)r lives, F)st as positive tho)"hts and actions lead to smooth sailin".

*f we donMt )nderstand the nat)re of this Fo)rney and the inner workin"s of the ship that is

o)r self, how can we hope to steer o)r co)rse/

Life is a *ust adenture

3ife is an advent)re, a F)st advent)re, and this is what makes it so challen"in". *f we

want to p)t in the reD)ired effort, we can Fo)rney to far:off places, e7plore marvelo)s

mysteries, and e7perience asto)ndin" deli"hts. @ot anywhere o)tside, tho)"h this

obvio)sly is possible too, b)t within o)r own conscio)sness. <f co)rse, a lon" Fo)rney is

made )p of many short steps. 4he overall direction of o)r life is determined by decisions

made every instant.

1e need to cast off the chains that limit )s by freein" o)rselves of whatever binds or

clo)ds o)r conscio)sness. 3ife is m)ch more than physical e7istence. 4he "reater o)r

)nderstandin" of what lies beyond materiality, the "reater will be o)r desire to act in ways

cond)cive to spirit)al )plift. <nce hot air balloonists have tasted the deli"ht of floatin"

freely thro)"h the skies, they release their ballast ea"erly. .s each earthbo)nd rope is

)ntied, the moment of soarin" "rows nearer.

1hat, then, yo) may ask, awaits )s beyond the confines of o)r present state of

conscio)sness/ 1ho has Fo)rneyed to the spirit)al realms/ .nd, from a practical point of

view, what keeps )s from followin" in their footsteps/ *f life r)ns by the law of ca)se and

effect, do certain actions wei"h down o)r so)l F)st as s)rely as sandba"s hold a balloon

fast to the earth/

1?

+nswering Life's $ig ,uestions

')lvin )nd 6obbes 1atterson. 6eprinted with permission of Gniversal !ress %yndicate. .ll ri"hts reserved.

4here are many important D)estions abo)t life. @ot s)rprisin"ly, only one who has

tr)ly lived can answer these D)estions. %adly, s)ch individ)als are few and far between.

4hey are the tr)e mystics, the !rofessors ;merit)s of %pirit)al %cience, men and women

who have e7perienced the f)ll potential of what life offers )s. *n every a"e they serve as a

link between the ethereal spirit)ality that is the s)preme reality, and the cr)de materiality

of earthly e7istence.

1hether &hristian, Hind), B)ddhist, 8ewish, 5)slim, or non:sectarian, at the heart of

their messa"e mystics espo)se a remarkably similar point of view. 1e are acc)stomed to

thinkin" of the differences between reli"ions and philosophies. 5any people reFect reli"ion

for this very reason: that it separates man from man.

B)t the divisive wran"lin" of theolo"ians is only foam tossed )p from the sea of )nity

known to the spirit)ally enli"htened. -God,0 for them, cannot be described in terms that

create differences. -God0 is the oneness behind all appearances. 4h)s it is not s)rprisin"

that those who have e7perienced what lies beyond mind and matter a"ree on what they

find there, while those who merely spec)late ar")e endlessly abo)t their ")esses.

-aps of !etap"ysical geograp"y

6eliable maps of metaphysical "eo"raphy do e7ist, b)t it takes a practiced eye to

reco"niEe them. ;ven an act)al road mapBthe kind yo)9d )se to "et aro)nd in a co)ntry

by carBbears almost no resemblance to the hi"hways on which one act)ally travels. 4he

tiny sD)i""les drawn on a few feet of paper may represent si7:lane freeways whose "iant

ribbons of asphalt and concrete traverse tho)sands of miles of mo)ntains, plains, and

16

(t is onl b m)8ing p!sic)l e9periments t!)t /e c)n discover t!e intim)te n)ture of

m)tter )nd its potenti)lities4 -nd it is onl b m)8ing psc!ologic)l )nd mor)l

e9periments t!)t /e c)n discover t!e intim)te n)ture of mind )nd its potenti)lities4 (n

t!e ordin)r circumst)nces of )ver)ge sensu)l life t!ese potenti)lities of t!e mind

rem)in l)tent )nd unm)nifested4 (f /e /ould re)li:e t!em1 /e must fulfil cert)in

conditions )nd obe cert)in rules1 /!ic! e9perience !)s s!o/n empiric)ll to be v)lid4

;in ever )ge t!ere !)ve been some men )nd /omen /!o c!ose to fulfil t!e conditions

upon /!ic! )lone1 )s ) m)tter of brute empiric)l f)ct1 suc! immedi)te [spiritu)l]

8no/ledge c)n be !)d< )nd of t!ese ) fe/ !)ve left )ccounts of t!e Re)lit t!e /ere

t!us en)bled to )ppre!end;&o suc! first%!)nd e9ponents of t!e +erenni)l +!ilosop!

t!ose /!o 8ne/ t!em !)ve gener)ll given t!e n)me of 2s)int5 or 2prop!et15 2s)ge5 or

2enlig!tened one45

B.ldo)s H)7ley

1

deserts. 4he dots sprinkled here and there alon" the sD)i""les often denote lar"e cities

with millions of people. Before we "o to a new co)ntry, it is impossible to comprehend

the vast three:dimensional reality of what we will e7perience by lookin" at a miniat)re

two:dimensional map.

*ma"ine, then, how diffic)lt it wo)ld be to -draw0 a map of hi"her states of reality.

1hen yo) remember a dream, isn9t it often ne7t to impossible to describe the landscape

and happenin"s within yo)r conscio)sness/ <ne freD)ently ends )p sayin" somethin" like,

-* was watchin" a soccer "ame, b)t it wasn9t like a match in any stadi)m that *9ve ever

seen.0 1ell, a statement like that doesn9t do m)ch to help another person )nderstand

what we9ve seen. B)t it9s the best we can do. .nd dreams are a lower order of reality

than wakin", bein" almost entirely personal and s)bFective.

%o mystics freD)ently end )p )sin" phrases like: -@ot this, not that,0 -Beyond

anythin" we can know, and anythin" we cannot know,0 -God is what is.0 %h)nnin"

words, Ken masters are said to strike their st)dents on the head with a stick to indicate

that some tr)ths only can be known thro)"h direct e7perience.

5ystics, to the h)man world, are akin to water birds who can traverse air, sea, and

land. Bein" free and f)lly developed in all respects, they are the real h)man bein"s,

e7amples of the )nlimited potential of the h)man condition. 4hey are at home in the

ethereal spheres of spirit)ality, the rarefied and s)btle re"ions of mind, and the cr)de

conditions of materiality. .ppearin" as normal h)man bein"s, they are free to soar far

beyond the confines of everyday conscio)sness. .rmed with direct knowled"e of hi"her

realities, they tell )s limited, earthbo)nd creat)res that what we call -life0 is b)t a drop in

the limitless sea of metaphysical e7istence.

,or the mystic, every state of lifeBmaterial, mental, and spirit)alBmakes sense. 3ife

does not make complete sense to )s beca)se we have no sense of the completeness of life.

*t9s that simple.

.f life is a !oie/ w"at's t"e plot# +nd w"o's t"e director#

*ma"ine tryin" to )nderstand the plot of a movie by watchin" only a few seconds from

the middle of the film. . woman p)lls o)t a ")n and shoots a man in the chest. He falls

to the floor, and she r)ns o)t the door. 4his tells )s nothin", aside from the obvio)s

physical motions of the actors. *s she a merciless assassin or a co)ra"eo)s heroine/ 1e

can9t tell )nless we know what came before and after this brief snippet of action. 4he bare

facts of the sit)ation are immediately obvio)s by watchin" the screen, b)t the meanin" of

those facts depends )pon a m)ch broader conte7t.

3ife is similar. 1hat we sense is m)ch less than what there is. 1e "et )nhappy,

conf)sed, and an7io)s beca)se we9re i"norant of the bi" pict)re. 8)st as lookin" at a few

frames of a motion pict)re will not tell yo) m)ch abo)t the plot, neither will "oin"

thro)"h everyday life enli"hten )s as to the meanin" of o)r e7istence. ,or this life we are

livin" now is no more than a tiny snippet of what we have been, and what we will be.

5any people believe that if they only knew all the details of their for"otten childhood,

they wo)ld somehow -know themselves.0 B)t re:r)nnin" the film of o)r c)rrent life even

back to the moment of conception is eD)ivalent to watchin" a co)ple of seconds of a two:

ho)r movie. *f this is not conFect)re, b)t a fact of spirit)al science, it be"s D)estions that

need some answer.

<ne of these D)estions is: 6o/ did m e)rt!l e9istence begin in t!e first pl)ce7

.nswerin" this D)ery wo)ld take )s a lon" way toward knowin" the deepest spirit)al

mysteries. 4he search for be"innin"s, after all, is the )ltimate D)est of any science.

!hysicists are not satisfied with )nderstandin" the laws of nat)re, b)t want to know how

those laws came to be and why different laws do not ")ide material e7istence.

17

&osmolo"ists are happy st)dyin" the formation of stars from primordial matter and

ener"y, b)t wo)ld be ecstatic if they co)ld know the secret of the Bi" Ban" which, they

consider, bro)"ht o)r )niverse into bein".

%imilarly, even if we co)ld watch a film of o)r lifeBor myriad of livesBfrom start to

finish Ia fri"htenin" prospect, especially witho)t bein" able to edit that movieJ, it really

wo)ld not tell )s all that m)ch abo)t o)rselves and the cosmos. 1here, or what, was *

before * came to be -me/0 @ow that *9ve finished watchin" the last reel of the epic, -5y

;7istence as 5e,0 and reached the present moment, what happens ne7t/ +oes this film

ever end/ .m * trapped in some sort of theatrical ni"htmare in which * play vario)s roles

for eternity/ .nd here is the bi""est D)estion of all:

(s t!ere ) director7

1e m)st, in other words, try to come to "rips with a basic iss)e: -1ho9s in char"e

here, anyway/0 5ovies don9t F)st sprin" o)t of nowhere. Behind the scenes there is a

screenwriter, a director, a prod)cer, and all of those other folks whose names appear in

the final credits. Gnfort)nately, the fifteen billion year:lon" showin" of -Gniverse: Bi"

Ban" to 6i"ht @ow0 lacks any readily apparent credit linesBperhaps beca)se o)r movie is

not over yet.

(a0ing up to reality is as si!ple as 12324

How, then, co)ld it ever be possible to confirm the tr)ths of spirit)al science/ *s there

any way to t)rn o)r attention away from the show of materiality in which we are so

en"rossed, and learn abo)t the so)rce of this marvelo)s prod)ction/

Hes, this can be done. *t9s simple as 1, , #, b)t it9s not easy.

=1> 'lose our ees )nd le)ve )side t!e outside /orld1 for t!)t cle)rl is m)teri)l )nd

l)c8s )n met)p!sic)l signific)nce4 &!is le)ds ou inside our consciousness?p!sic)l

sig!ts1 sounds1 )nd ot!er sensor impressions !)ving been left be!ind4

=@> "it!in our consciousness1 elimin)te evert!ing person)l# t!oug!ts1 emotions1

im)ginings1 concepts1 im)ges1 memories1 )nd )nt!ing else pert)ining eit!er to t!e

ob.ective outside /orld1 or our sub.ective inner /orld4

=3> Simpl be )/)re of /!)t rem)ins in our consciousness4 &!is /ill be ob.ectivel

re)l1 bec)use it isnAt person)l4 -nd it /ill be met)p!sic)l1 bec)use it !)s no connection

/it! )n sensor impression or t!oug!t of t!e m)teri)l /orld4

&on"rat)lationsL Ho) may now be described as a realiEed h)man bein".

1ell, if yo)9re thinkin", -4here m)st be more to realiEation than this,0 yo)9re correct.

8)st as a scientific e7periment reD)ires caref)l preparation before it can be cond)cted

properly, so, as we have already disc)ssed, m)st an aspirin" spirit)al scientist form his or

her conscio)sness into a s)itable instr)ment for observin" hi"her states of reality.

1ron" actions, beca)se they brin" with them a chain of ne"ative reactions, or the

-sins0 of reli"io)s terminolo"y, are the anchors which keep o)r conscio)sness st)ck in the

dense m)ck of physical reality. *t is as if someone asked &hristopher &ol)mb)s, -1hat

relation co)ld there be between the anchors on yo)r ships, the BiC), +int)1 and S)nt)

0)ri), and yo)r findin" the @ew 1orld/0 . s)itable reply wo)ld have been, -1ell, my

friend, )ntil * raised those anchors * was bo)nd to the shore of %pain. 1ith the anchors

)p, my ships were free to set forth on a historic voya"e of discovery.0

5eality is real% 5eally6

4he cr)7 of the matter is this: metaphysical or spirit)al reality is not some far:off

fantasy land with no connection to everyday life. %pirit)al laws of e7istence shape the

physical laws of nat)re, and o)r own inner conscio)sness. 4hey are part of the str)ct)re

of the cosmos, not abstract concepts that can be reFected or accepted as we please. Aarma

1(

Bthe principle that each action prod)ces an eD)ivalent reactionBcontrols everythin"

mental and material, and is as impossible to avoid as "ravity.

*t doesn9t matter in the sli"htest if someone believes in "ravity, or not. *f he falls off

the roof, he hits the "ro)nd, !)rd. %imilarly, it doesn9t matter in the sli"htest if someone

believes in karma, or not. *f he "oes a"ainst the nat)re of life, he reaps the conseD)ence,

suffering.

Gravity, however, is an accepted scientific fact. Aarma, bein" a s)btle law of hi"her

conscio)sness, is not known to material science. *ma"ine a worker who wants to warn

passers:by abo)t the dan"er of standin" on a sidewalk directly )nder a "rand piano

perched on the ed"e of a hi"h roof. 4his warnin" will make immediate sense to anyone

familiar with the law of "ravity: since heavy obFects fall with a lar"e force, it is wise to "et

o)t of the way of anythin" s)bstantial that is abo)t to hit yo)r head. ;ven if the worker

simply pointed at the teeterin" piano, those familiar with the way "ravity worksBwhich

incl)des almost everyoneBwo)ld "et the warnin".

B)t the metaphysical law of karma is m)ch less )nderstood than "ravity, since its

operation is evident only by e7pandin" o)r conscio)sness. 4hat is why we have to

address so e7tensively the D)estion -1hat is 3ife/0 before we can appreciate how s)btle

spirit)al laws shape physical laws, and thro)"h this means always ret)rn to )s the F)st

conseD)ences of o)r tho)"hts and actions. <nly if we have some idea of the complete

pict)re will we see that these conseD)ences are not at all arbitrary, F)st as "ravity does not

operate on a whim. 5orality may appear as a matter of personal choice, b)t its

conseD)ences are b)ilt into the very fabric of reality.

5ising aboe t"e fog of !ind and !atter

,rom the spirit)al perspective, virt)e and sin, or ri"ht and wron" actions, are not

s)bFective concepts that each person can look )pon in their own way. 4hey are obFective

aspects of e7istence that can be i"nored, b)t not escaped. Ho) are free to keep yo)r eyes

on the sidewalk and i"nore fallin" pianos. However, fallin" pianos are not free to i"nore

the law of "ravity, nor is yo)r body free to i"nore the effect of a tho)sand po)nds of

wood and metal fallin" on it. .nd neither can we avoid e7periencin" pleas)re and pain,

health and disease, Foy and sadness, after havin" en"a"ed in the actions which ca)sed

those effects.

<)r condition is akin to walkin" alon" a street that is covered with a blanket of dense

fo". 4he fo" e7tends only ten feet or so above "ro)nd level, b)t that is taller than we are,

so we can see only a little of what is ahead of or behind )s, and nothin" at all of what lies

above o)r heads. .s we walk, s)rprises keep droppin" thro)"h the veil of fo". Here

comes a cascade of rose petals. How lovelyL @ow there is a torrent of hot coals. How

awf)lL ,ra"rant droplets of sweetly scented perf)me s)rro)nd )s for a while. 1e smile in

deli"ht. 4hen a p)n"ent odor descends which makes )s feel sick.

4his is the normal co)rse of life. <)r vision is clo)ded beca)se we e7perience only

the physical reality. 1e move alon" )ncertain of what is comin" )p ne7t. !leasant and

painf)l events rain down on )s, often witho)t o)r bein" s)re from where they have come.

1e are )nable to see whoever, or whatever, is above the fo" of o)r i"norance, or why and

how vario)s obFects descend thro)"h that fo" and enter o)r life. 4hese mysteries can

never be solved by simply thinkin" or perceivin". How can yo) fi")re o)t what is above

the fo" of materiality when yo) have no knowled"e that anythin" above physical reality

e7ists/ How can yo) see the hei"hts when yo)r eyes cannot penetrate the clo)ds of

)nknowin" that s)rro)nd yo)/

%o we t)rn to the spirit)al scientist. 4o "et above the fo" bank of this physical

)niverse and o)r mental misconceptions, we need to be receptive to the ")idance of those

1'

people who, thro)"h a practice of contemplative meditation, e7pand their conscio)sness

)ntil they are able to e7perience the complete pict)re.

Science is partial trut"7 !ysticis! is co!plete trut"

Birds and skydivers have a m)ch broader view of earth than rabbits and hikers.

%imilarly, tho)"h what we e7perience in the everyday world is real, mystics say it is a

weak reflection of )ltimate reality. .nd while the knowled"e of material science is tr)e, it

constit)tes F)st a small proportion of the absol)te tr)th.

%o let )s e7amine vario)s aspects of the bi" D)estion, -1hat is 3ife/,0 from both

points of view. ;ach D)estion will be"in with an overview of the obvio)s b)t partial

answer from material science, and then describe the more complete pict)re that comes

with the spirit)al perspective.

6emember, however, that both spirit)al and material science view reality as an

)nbroken whole. ;very part of e7istence is related to every other part in some way.

Gnderstandin" the nat)re of this -some way0 is the final "oal of researchers in either

science. <ne discipline )s)ally calls the power which holds everythin" to"ether -God;0

the other discipline often terms that power the -4heory of ;verythin".0 6e"ardless, the

"enerally reco"niEed fact that a sin"le reality lies behind the m)ltiplicity of appearances

has a cr)cial implication: it is impossible to completely fathom life by breakin" it into

parts.

<ne either "rasps )ltimate tr)th as a whole, or not at all.

.nd even when an attempt is made to describe less:than:)ltimate tr)th, foc)sin" on

parts obsc)res the whole. %o don9t be concerned if yo) find yo)rself wonderin" how the

followin" D)estions, which may seem disFointed, fit to"ether. .fter breakin" life into

pieces, the ne7t chapter will assemble those pieces into a complete pict)re.

("y is t"ere so!et"ing/ rat"er t"an not"ing#

Obvious and partial truth. Before delvin" into the details of what life is all abo)t, the

D)estion arises, -1hy is there anythin" at all, incl)din" lifeBand h)mans who ponder the

meanin" of life/0 4hat is, we tend to take e7istence itself for "ranted. Het the central

mystery that faces both scientists and mystics is how bein" came to be. *nterestin"ly, we

refer to o)rselves as h)man beings, perhaps o)t of a reco"nition that raw e7istence is the

fo)ndation that s)pports people and everythin" else in the cosmos.

@evertheless, some scientists believe that the )niverse always has e7isted, so it is

meanin"less to ask this D)estion, F)st as it is senseless to ask what time it wo)ld be when

infinity ends. B)t this still be"s the D)estion of why the -somethin"0 that s)rro)nds )s,

and is )s, e7ists at all, even if nat)re is infinite. %o science Iin this section we call material

science -science,0 and spirit)al science -mysticism0J either has to ass)me that the )niverse

has e7isted eternally in one form or another, or p)t forward theories s)ch as the Bi" Ban"

which raise as many D)estions as they p)rportedly answer.

,or e7ample, ass)me it is tr)e that the physical )niverse spran" into e7istence at the

moment of the Bi" Ban" some ten to fifteen billion years a"o. .nd since its birth the

)niverse has contin)ed to e7pand from a speck m)ch smaller than an atom to an

)nima"inable vastness containin" billions )pon billions of "ala7ies. However, we still

m)st ask, -1hat prod)ced the tremendo)s ener"y of the Bi" Ban", and where did t!)t

force come from/0 %cientists have not come close to answerin" this D)estion, callin" it

-metaphysical,0 since whatever prod)ced the time and space in which we now reside

obvio)sly transcends the ordinary laws of nat)re.

>)ite tr)e. B)t metaphysical is not the same as non:e7istent. .nd bein" )nable to

answer a D)estion does not mean that the D)estion is )nanswerable.

C

Subtle and complete truth. -God0 knows why creation e7ists. 4hat isn9t an offhand

statement. *t9s the tr)th. 5ysticism teaches that one can indeed know why there is

somethin" rather than nothin", b)t this is only possible by att)nin" oneself to the

conscio)sness of the creative power that ca)sed the creation.

5ystics a"ree with many physicists that the essence of the cosmos has e7isted

eternally. %ometimes, if it even makes sense to speak of time in the conte7t of eternity,

this essence takes on form, and becomes the creation. %ometimes -God0 remains an

)ndivided )nity, a wholeness witho)t parts, )nmanifest, beyond all description.

*nsofar as words can e7press spirit)al realities, mystics describe e7istence as God9s

play. 4his can be taken in several ways. <ne is that creation is a Foyf)l e7pression of the

creator9s infinite wisdom and power. .nother is that creation is directed: the c)rtain of

life rises and falls accordin" to a divine desi"n.

Babies learn how they were born only when they "row )p and are capable of

)nderstandin" the answer. %imilarly, o)r h)man conscio)sness m)st be raised to a

different state before we can comprehend the reason for creation. %till, even if we cannot

yet comprehend the intelli"ence which bro)"ht o)r )niverse, and m)ch more, into

e7istence, it is possible to "rasp that all we see aro)nd )s came into bein" for some

p)rpose, not by chance. 1e can learn somethin" from bein" alive, and the physical

creation is o)r classroom. ;ven more, reality is not only the teacher b)t the schoolho)se

as well, which brin"s )s to the ne7t D)estion.

("at is t"e 8so!et"ing9 fro! w"ic" existence is !ade#

Obvious and partial truth. %cience holds that everythin" in o)r )niverse, the only

part of e7istence that concerns the material sciences, is composed of matter. 4his is why

most scientists profess a materialistic philosophy of life. -1hat else is there/0 they ask.

1ell, it is accepted that matter and ener"y are eD)ivalent, as shown by ;instein9s famo)s

eD)ation: ;Iner"yJ N 5IassJ times &Ispeed of li"htJ

. %o it is F)st as acc)rate to say that

the )niverse is made of ener"y. 6e"ardless, science "enerally ass)mes that stars, and

rocks, and "oldfish, and ladyb)"s, and comp)ters, and brains, and everythin" else on and

off of earth, consist solely of physical matterOener"y.

However, some material thin"s are alive, and some are not. 4his is a bi" problem for

science. How co)ld life arise from inanimate matter/ <ne hypothesis, amon" many, is

that life was sparked into e7istence by li"htnin" strikin" some sort of chemical so)p in the

earth9s primeval oceans. 4his notion is appealin"Bespecially to those who enFoy

,rankenstein moviesBb)t has si"nificant loose ends.

Basically, it is e7tremely diffic)lt for science to )nderstand how the comple7ity of self:

reprod)cin" life "rows o)t of m)ch simpler inert matter. *t is as if yo) took a pile of

electronic parts, shook them to"ether in a paper ba", and o)t came a radio that not only

worked perfectly, b)t also co)ld prod)ce little baby radios. 4he odds of this happenin" by

chance are F)st abo)t Eero, yet this is the prevailin" scientific view of how life be"an.

,)rther, this radio analo"y doesn9t even address the iss)e of conscio)sness.

1hatever conscio)sness is, and the material sciences don9t have an answer to that

D)estion either, yo) are e7periencin" it at this very moment. +oes yo)r conscio)sness

seem to have the same -flavor0 to it as does the feel of a rock, or the Folt from electricity/

@o. Het science "enerally ass)mes that somethin" so ethereal arose from cr)de matter

and ener"y. ,ailin" to believe that conscio)sness simply was present at the moment of the

Bi" Ban", scientists m)st labor mi"htily to e7plain how it was prod)ced m)ch later in the

life of the )niverse.

Subtle and complete truth% 5ysticism a"rees with science that matter and ener"y

make )p physical e7istence. B)t mystics say there is more. .ll matter is intimately

1

connected with spirit in that everythin" is enlivened by spiritMs all:pervadin", vital ener"y.

4hose parts of the creation that are knowin" may be described as havin" a so)l. *t is the

knowin" parts of the creationBpeople, animals, plants, insectsBthat we "enerally term

alive. 4he mystic "oes so far as to say that matter, mind, and so)l are varyin" aspects of a

sin"le s)bstance: spirit. 4he easiest way to )nderstand this is to think of water, which is

known to chemists as H

< since each molec)le of water has two atoms of hydro"en and

one atom of o7y"en.

.nyone with a stove and a freeEer can confirm that water can e7ist as either a liD)id, a

solid IiceJ, or a "as IvaporJ. Heat an ice c)be above # , and it t)rns to liD)id; heat the

liD)id water to 1 , and it t)rns to vapor, or steam. B)t water always remains H

< no

matter how its appearance chan"es. %o we sho)ldn9t be all that s)rprised when mystics tell

)s that everythin" in e7istence, evert!ing1 is composed of spirit. 5atter, so to speak, is

-froEen0 spirit; mind is -liD)id0 spirit; and the so)l is -"aseo)s0 spirit.

1hat, tho)"h, is spirit itself/ 1hen the ocean of )ltimate reality IGodJ stirs in an act

of creation, a wave of spirit IGod:in:.ctionJ forms. 8)st as a wave possesses the same

attrib)tes as the ocean, so does the creative power of spirit reflect the omnipresence,

omniscience, and omnipotence of the s)preme reality from which it has arisen. %o

scientists are correct in viewin" the physical )niverse as made of ener"y. B)t physical

ener"y is stepped:down from the m)ch more potent spirit)al ener"y, F)st as a transformer

converts ho)se c)rrent into a weaker form of electricity.

%pirit, however, is not like an electrical c)rrent that flows only alon" wire pathways,

or water that is restricted to the bed of a river channel. @o, spirit is more like an

electroma"netic wave, s)ch as radio or television si"nalsBthe positive ener"y of creation

that fills all of space. ,)rther, and this is almost impossible to vis)aliEe, spirit not only fills

all of space, b)t creates space and time itself as it moves away from its p)re so)rce.

4h)s spirit)ality is not somethin" abstract, concept)al, other:worldly, or p)rely

metaphysical. 6ather the st)dy of spirit, which is tr)e spirit)ality, is the st)dy of reality.

,or whether spirit appears in the ")ise of matter, ener"y, mind, or as itselfBformless and

namelessBeverythin" in e7istence is composed of that all:pervadin" vital ener"y. %o

mysticism has no diffic)lty e7plainin" how life appeared on earth. %pirit is the positive

essence of life, the ever:livin" God. 3ife creates life, ri"ht down the scale.

*n this sense even s)b:atomic particles are alive, as are rocks and beams of li"ht. B)t

mystics e7plain that all life:forms that have what we call -life0 possess a D)ality that

matter and ener"y lack. *t is as if they e7ist above a partic)lar threshold of comple7ity,

and this we call havin" a so)l. 3ivin" entities have within them a 8no/ing spark of God9s

eternal fire. 4his makes plants, insects, animals, h)mans and other forms of life )niD)ely

akin to God. %o when we kill, we e7tin")ish the sacred fire of life; we sla)"hter somethin"

divine.

<f co)rse this philosophy, when taken to the e7treme, wo)ld make it impossible to

live a normal life, or even live at all. Ho) cannot "ive )p p)llin" weeds, swattin"

mosD)itoes, or eatin" ve"etables. *t is the reality of this world that one form of life can

e7ist only by in"estin" another form Ie7cept for plants which, aside from =en)s fly traps

and the like, s)bsist on raw matter and ener"y.J

However, if we s)stain o)rselves on hi"her forms of life that have a developed

conscio)snessBeven if we do not do the sla)"hterin" o)rselvesBthe pain and s)fferin"

they e7perience rebo)nds )pon )s. .ction prod)ces reaction, and it is we who initiate

s)fferin" and death by o)r demand. 1hatever distress we ca)se somehow is re"istered in

o)r conscio)sness, where it has to reappear one day and ca)se )s an eD)ivalent amo)nt of

pain.

4hat we have to take life to live is clearly a fact, b)t there is a bi" difference between

sla)"hterin" a cow and a carrot. .s the demand for food obvio)sly creates the s)pply, this

difference has enormo)s conseD)ences. 1hether we want to rise beyond the cr)dity of

physical e7istence and e7perience p)rer levels of spirit)ality, or simply be happy on this

earth, it is in o)r interest to avoid actions that lead to painf)l conseD)ences.

)ow !any states of reality exist#

Obvious and partial truth. &learly a physical reality e7ists, for we are livin" in it now.

*t is immediately apparent thro)"h the five senses. 1e can feel the hardness of rocks, see

the colors of flowers, hear the cries of birds, smell the fra"rance of perf)me, and taste the

sweetness of a berry. %cientists ma"nify the power of the senses thro)"h technolo"y,

which allows them to see faint "ala7ies billions of li"ht years away or feel the min)te

movement of a sli"ht earthD)ake. 4hese observations, of co)rse, are noted by somethin"

called the -mind,0 which certainly seems to be a different type of reality than material

e7istence.

However, most scientists consider the seemin"ly non:physical nat)re of the mind to be

an ill)sion prod)ced by the comple7 interaction of cells in the brain. 4he mind, they say,

really is F)st a kind of ne)ro:chemical sensation res)ltin" from all of the activity "oin" on

in the brain. 8)st as si"ht is a physical reaction to li"ht, and hearin" a reaction to so)nd,

so are tho)"hts, emotions, and other mental states a reaction to the transmission of

chemical si"nals within the brain. %o this doesn9t leave room for any reality other than the

material forces of nat)re. ;ven tho)"h mathematicians and physicists theoriEe abo)t

hi"her dimensions of reality, these are considered to be -ima"inary0 in the sense that no

one ever co)ld e7perience them directly.

Subtle and complete truth. 5ysticism teaches that not only is this viewpoint of

science incomplete, it is very misleadin". *n tr)th the mind is most definitely not an

ill)sory offshoot of the brain, nor is physical e7istence the solid fo)ndation of reality.

6ather, the brainBand everythin" else made of matterBis a reflection of a more real level

of e7istence, m)ch as a mirror reflects a two:dimensional ima"e of whatever three:

dimensional obFect is in front of it. <)r material world is an ima"e of a hi"her mental

reality.

*n other words, mind comes first and "ives rise to matter. 4his is not a personal mind

like yo)rs and mine, b)t an impersonal level of conscio)sness called )niversal mind.

;verythin" in the physical world has its be"innin"s in this hi"h mental sphere. 4he

)niversal mind contains the root ca)se of everythin" in the physical )niverse and other

non:material planes that lie between it and the physical world. 4hese intermediary planes

or de"rees of conscio)sness act as steppin" stones, so to speak, between two very

different levels of bein": p)re mind and physical matter.

5ysticism teaches that there are many levels of conscio)sness beyond o)r physical

)niverse; there is not F)st one -heaven.0 4he place where people "o after death, or in a

near:death e7perience, is only the first floor of the immensely tall skyscraper of &reation.

%tartin" from o)r everyday level of conscio)sness, each realm is e7perienced as more

bea)tif)l and l)mino)s as the presence of p)re spirit increases. ;ach level is more refined

than the one before. .s 8es)s said, -*n my ,ather9s ho)se are many mansions.0 I8ohn

1$:J 1itho)t knowin" how to rise )pward on the elevator of spirit, it is easy for

someone F)st enterin" the many spirit)al planes to believe they have reached the kin"dom

of God.

4hese refined planes of e7istence are not an idea, or some abstract theolo"ical

concept. 4hey are act)al levels of bein" which can be entered and e7plored by anyone

who knows how to e7perience them. <ne m)st nat)rally )se a non:physical means of

travellin" to these metaphysical re"ions, a practice that develops the spirit)al fac)lties that

#

are intrinsic to oneMs conscio)sness.

,or this reason these domains are better tho)"ht of as states of conscio)sness than as

some "hostly version of the physical world. .s dreamin" coe7ists with wakin" Iyo) can

move between these two states of conscio)sness easily, especially when yo)9re tiredJ, so

do hi"her realms of bein" coe7ist with the everyday world.

However, F)st as it is m)ch easier to "et in a canoe and float downstream rather than

paddle )pstream, so is enterin" a lower state of conscio)snessBsleep and dreamin"B

m)ch easier than reachin" a hi"her state thro)"h meditation. 4his is why few people are

able to directly e7perience these planes of reality. 5any talk abo)t them, or claim that

some an"el or other entity has told them all abo)t these heavenly re"ions, b)t this is very

different from "oin" there at will. *ma"ination is not reality, nor is hearsay solid evidence.

*t is only when we pro"ress beyond the mental sphere, the realm of )niversal mind and

the framework of everythin" below it, that we act)ally e7perience a state of p)re spirit.

<nly then can the ineffable state of @irvana, or p)re conscio)sness, be e7periencedBGod:

as:God.

5ystics say, tr)ly, this can9t be ima"ined. 4o know s)ch a reality, it m)st be

e7perienced. 4he p)rpose in even mentionin" it is to impress )pon the reader that

whatever we believe we know abo)t creation, it isn9t m)ch. .ccordin" to the mystics, o)r

)nderstandin" of life is e7tremely limited. ;ven worse, most of )s are completely i"norant

of o)r i"norance. 1e hold onto a l)mp of clay when diamonds are within o)r reach. .ll

we need to do is let "o of the one and take hold of the other. B)t those spirit)al "ems

cannot be "rasped with o)r physical hands. %o it is time to ask, -1hat are we made of/

,lesh, bone, and blood, or that and somethin" more/0

("at is a "u!an being#

Obvious and partial truth. 1e are a physical body. 4his m)ch is clear as * watch the

fin"ers of my hands type o)t these words. 4hese hands are connected to arms, the arms

to a tr)nk, and this whole con"lomeration is ")ided by an entity known as -me0 who

seems to reside within my head, or brain. 4his is tr)e for yo) as well, even tho)"h the

shape and siEe of o)r bodies may be very different. ;very person has some sort of

physical body, tho)"h parts of itBs)ch as an arm, le", or breastBmay be missin" d)e to

an accident, illness, or birth defect.

B)t when o)r brain is missin", or dead, scientists consider that /e are "one also. %o

this clearly is the most important part of the h)man body. Brain death is "enerally

considered by doctors to mark the end of life, even tho)"h the l)n"s, heart and other vital

or"ans still are f)nctionin". .nd when people talk abo)t their event)al death, most are

more afraid of losin" their mind in old a"e, than of s)fferin" some sort of physical

disability. 4h)s it seems evident that even tho)"h o)r body is essential for life, a body

witho)t a mindBwhich seems to prod)ce o)r sense of personal identityBco)ld hardly be

called a h)man bein".

.s was noted previo)sly, the bi" D)estion is this, -.re we made )p of anythin" other

than the physical matter that constit)tes o)r body/ 1hat does prod)ce o)r Ph)manness9 if

it isn9t physical matter/0

%cience cannot answer that D)estion, beca)se it takes on face val)e the evident fact

that when a person9s body dies, whatever seemed to inhabit that body also dies. 1hen a

h)man is no lon"er livin", the person who apparently inhabited his physical form cannot be

fo)nd. %o it appears reasonable to ass)me that we have no e7istence apart from o)r

body, which nat)rally implies that death is to be feared, rather than welcomed. *f it is bad

eno)"h to lose part of one9s mind thro)"h senility or .lEheimer9s disease, it seemin"ly

wo)ld be m)ch worse to lose )ll of yo)r mind and sense of personal identity at the time of

$

death.

4he @ew Horker &ollection 1''7 6obert 5ankoff from cartoonbank.com. .ll ri"hts reserved.

Subtle and complete truth4 4hankf)lly, the mystic says, we are m)ch more than a

b)nch of chemical elements packa"ed to"ether in a clever fashion and "iven the ability to

move, sense, and think for a few decades of life before ceasin" to e7ist and disinte"ratin"

into nothin"ness. 4he tr)th is that matter, o)r body, is only a flimsy shell that temporarily

encases other livin" realities which possess m)ch more permanence and vitality than the

physical form.

.fter the death of o)r physical body, we find o)rselves in a more refined state of bein"

that is sometimes referred to as o)r -astral0 form, meanin" -of the stars.0 *t is called this

beca)se the astral body is described as sparklin" with millions of particles resemblin" star

d)st. *n some sense it resembles o)r previo)s physical form b)t is more l)mino)s and

bea)tif)l. !l)sBand this is really "ood newsBthe astral form doesn9t s)ffer from diseases

or other ailments. B)t in other respects, since the same mind as we have now is still with

)s, o)r h)man stren"ths and weaknesses remain with )s after death.

4his means that the time we spend at this level of conscio)sness is temporary. *f o)r

mind reflects stron" earthly habits, desires and attachmentsBand )s)ally this is the caseB

then before too lon" we will find o)rselves reincarnated into another physical body. 3ife

"ives )s what we deserve thro)"h the perfectly F)st law of karma. Beca)se most people

lean decidedly more toward the worldly than the spirit)al, it follows that the "eneral

co)rse after death is back -down0 to earth, or the physical plane. 4hose, however, who

have been able to free their mind si"nificantlyBwho have spirit)al rather than worldly

tendenciesBmay have reached the level of p)rity necessary to move -)p0 to hi"her

realms.