Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Aristotle On Tragedy

Hochgeladen von

SamBuckleyOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Aristotle On Tragedy

Hochgeladen von

SamBuckleyCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Aristotle on Tragedy

In the Poetics, Aristotle's famous study of Greek dramatic art, Aristotle (384-322

B.C.) compares tragedy to such other metrical forms as comedy and epic. He

determines that tragedy, like all poetry, is a kind of imitation (mimesis), but adds

that it has a serious purpose and uses direct action rather than narrative to achieve

its ends. He says that poetic mimesis is imitation of things as they could be, not as

they are for example, of universals and ideals thus poetry is a more

philosophical and exalted medium than history, which merely records what has

actually happened.

The aim of tragedy, Aristotle writes, is to bring about a "catharsis" of the spectators

to arouse in them sensations of pity and fear, and to purge them of these

emotions so that they leave the theater feeling cleansed and uplifted, with a

heightened understanding of the ways of gods and men. This catharsis is brought

about by witnessing some disastrous and moving change in the fortunes of the

drama's protagonist (Aristotle recognized that the change might not be disastrous,

but felt this was the kind shown in the best tragedies Oedipus at Colonus, for

example, was considered a tragedy by the Greeks but does not have an unhappy

ending).

According to Aristotle, tragedy has six main elements: plot, character, diction,

thought, spectacle (scenic effect), and song (music), of which the first two are

primary. Most of the Poetics is devoted to analysis of the scope and proper use of

these elements, with illustrative examples selected from many tragic dramas,

especially those of Sophocles, although Aeschylus, Euripides, and some playwrights

whose works no longer survive are also cited.

Several of Aristotle's main points are of great value for an understanding of Greek

tragic drama. Particularly significant is his statement that the plot is the most

important element of tragedy:

Tragedy is an imitation, not of men, but of action and life, of happiness and misery.

And life consists of action, and its end is a mode of activity, not a quality. Now

character determines men's qualities, but it is their action that makes them happy or

wretched. The purpose of action in the tragedy, therefore, is not the representation

of character: character comes in as contributing to the action. Hence the incidents

and the plot are the end of the tragedy; and the end is the chief thing of all. Without

action there cannot be a tragedy; there may be one without character. . . . The plot,

then, is the first principle, and, as it were, the soul of a tragedy: character holds the

second place.

Aristotle goes on to discuss the structure of the ideal tragic plot and spends several

chapters on its requirements. He says that the plot must be a complete whole

with a definite beginning, middle, and end and its length should be such that the

spectators can comprehend without difficulty both its separate parts and its overall

unity. Moreover, the plot requires a single central theme in which all the elements

are logically related to demonstrate the change in the protagonist's fortunes, with

emphasis on the dramatic causation and probability of the events.

Aristotle has relatively less to say about the tragic hero because the incidents of

tragedy are often beyond the hero's control or not closely related to his personality.

The plot is intended to illustrate matters of cosmic rather than individual

significance, and the protagonist is viewed primarily as the character who

experiences the changes that take place. This stress placed by the Greek tragedians

on the development of plot and action at the expense of character, and their general

lack of interest in exploring psychological motivation, is one of the major differences

between ancient and modern drama.

Since the aim of a tragedy is to arouse pity and fear through an alteration in the

status of the central character, he must be a figure with whom the audience can

identify and whose fate can trigger these emotions. Aristotle says that "pity is

aroused by unmerited misfortune, fear by the misfortune of a man like ourselves."

He surveys various possible types of characters on the basis of these premises, then

defines the ideal protagonist as

. . . a man who is highly renowned and prosperous, but one who is not pre-

eminently virtuous and just, whose misfortune, however, is brought upon him not by

vice or depravity but by some error of judgment or frailty; a personage like Oedipus.

In addition, the hero should not offend the moral sensibilities of the spectators, and

as a character he must be true to type, true to life, and consistent.

The hero's error or frailty (harmartia) is often misleadingly explained as his "tragic

flaw," in the sense of that personal quality which inevitably causes his downfall or

subjects him to retribution. However, overemphasis on a search for the decisive flaw

in the protagonist as the key factor for understanding the tragedy can lead to

superficial or false interpretations. It gives more attention to personality than the

dramatists intended and ignores the broader philosophical implications of the typical

plot's denouement. It is true that the hero frequently takes a step that initiates the

events of the tragedy and, owing to his own ignorance or poor judgment, acts in

such a way as to bring about his own downfall. In a more sophisticated philosophical

sense though, the hero's fate, despite its immediate cause in his finite act, comes

about because of the nature of the cosmic moral order and the role played by

chance or destiny in human affairs. Unless the conclusions of most tragedies are

interpreted on this level, the reader is forced to credit the Greeks with the most

primitive of moral systems.

It is worth noting that some scholars believe the "flaw" was intended by Aristotle as

a necessary corollary of his requirement that the hero should not be a completely

admirable man. Harmartia would thus be the factor that delimits the protagonist's

imperfection and keeps him on a human plane, making it possible for the audience

to sympathize with him. This view tends to give the "flaw" an ethical definition but

relates it only to the spectators' reactions to the hero and does not increase its

importance for interpreting the tragedies.

The remainder of the Poetics is given over to examination of the other elements of

tragedy and to discussion of various techniques, devices, and stylistic principles.

Aristotle mentions two features of the plot, both of which are related to the concept

of harmartia, as crucial components of any well-made tragedy. These are "reversal"

(peripeteia), where the opposite of what was planned or hoped for by the

protagonist takes place, as when Oedipus' investigation of the murder of Laius leads

to a catastrophic and unexpected conclusion; and "recognition" (anagnorisis), the

point when the protagonist recognizes the truth of a situation, discovers another

character's identity, or comes to a realization about himself. This sudden acquisition

of knowledge or insight by the hero arouses the desired intense emotional reaction

in the spectators, as when Oedipus finds out his true parentage and realizes what

crimes he has been responsible for.

Aristotle wrote the Poetics nearly a century after the greatest Greek tragedians had

already died, in a period when there had been radical transformations in nearly all

aspects of Athenian society and culture. The tragic drama of his day was not the

same as that of the fifth century, and to a certain extent his work must be construed

as a historical study of a genre that no longer existed rather than as a description of

a living art form.

In the Poetics, Aristotle used the same analytical methods that he had successfully

applied in studies of politics, ethics, and the natural sciences in order to determine

tragedy's fundamental principles of composition and content. This approach is not

completely suited to a literary study and is sometimes too artificial or formula-prone

in its conclusions.

Nonetheless, the Poetics is the only critical study of Greek drama to have been made

by a near-contemporary. It contains much valuable information about the origins,

methods, and purposes of tragedy, and to a degree shows us how the Greeks

themselves reacted to their theater. In addition, Aristotle's work had an

overwhelming influence on the development of drama long after it was compiled.

The ideas and principles of the Poetics are reflected in the drama of the Roman

Empire and dominated the composition of tragedy in western Europe during the

seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Joni Mitchell TuningsDokument4 SeitenJoni Mitchell TuningsSamBuckley33% (3)

- Musical Notes and SymbolsDokument17 SeitenMusical Notes and SymbolsReymark Naing100% (2)

- In Dreams Begin ResponsibilitiesDokument4 SeitenIn Dreams Begin ResponsibilitiesmarbacNoch keine Bewertungen

- Imitation and CatharsisDokument3 SeitenImitation and CatharsisIndulgent EagleNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is Aristotle's Definition of TragedyDokument12 SeitenWhat Is Aristotle's Definition of TragedyRamesh MondalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristptle's Concept of CathersisDokument7 SeitenAristptle's Concept of CathersisRamesh Mondal100% (1)

- The Rime of The Ancient Mariner by ColeridgeDokument2 SeitenThe Rime of The Ancient Mariner by Coleridgeflory73Noch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle's Concept of TragedyDokument1 SeiteAristotle's Concept of TragedyDaniel BoonNoch keine Bewertungen

- TragedyDokument7 SeitenTragedyAR MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle Concept of TragedyDokument9 SeitenAristotle Concept of Tragedykamran khanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle's PoeticsDokument22 SeitenAristotle's PoeticsAngel Marie100% (1)

- Components of Tragedy in AristotleDokument3 SeitenComponents of Tragedy in AristotleRazwan ShahadNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rime of The Ancient Mariner Final DraftDokument7 SeitenThe Rime of The Ancient Mariner Final Draftsms2002arNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ars PoeticaDokument3 SeitenThe Ars PoeticaVikki GaikwadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Global Supply Chain Top 25 Report 2021Dokument19 SeitenGlobal Supply Chain Top 25 Report 2021ImportclickNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appreciation John Donne Good Friday 1613Dokument3 SeitenAppreciation John Donne Good Friday 1613Rulas Macmosqueira100% (1)

- Warlock of LoveDokument62 SeitenWarlock of LoveMatthew Shannon83% (6)

- Paradise LostDokument6 SeitenParadise Lostrizalstarz100% (3)

- Citizen's Army Training (CAT) Is A Compulsory Military Training For High School Students. Fourth-Year High SchoolDokument2 SeitenCitizen's Army Training (CAT) Is A Compulsory Military Training For High School Students. Fourth-Year High SchoolJgary Lagria100% (1)

- M-02.Aristotle's Poetic Concept - An Analysis of Poetry (ENG) PDFDokument15 SeitenM-02.Aristotle's Poetic Concept - An Analysis of Poetry (ENG) PDFAshes MitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 9 &10 - Gene ExpressionDokument4 SeitenChapter 9 &10 - Gene ExpressionMahmOod GhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outline of AristotleDokument3 SeitenOutline of AristotleSaakshi GummarajuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle Concept of TragedyDokument2 SeitenAristotle Concept of TragedyMuhammad SaadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle On TragedyDokument11 SeitenAristotle On TragedyNoel EmmanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 4 Lesson ProperDokument44 SeitenChapter 4 Lesson ProperWenceslao LynNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle's PoeticsDokument5 SeitenAristotle's Poeticskhushnood ali100% (1)

- Hamlet Act 1 2 and SoliloquyDokument2 SeitenHamlet Act 1 2 and Soliloquyapi-240934338100% (1)

- PoeticsDokument4 SeitenPoeticsCalvin PenacoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Criticism of PlatoDokument3 SeitenLiterary Criticism of PlatoBam DeduroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle's Poetics AnalysisDokument5 SeitenAristotle's Poetics AnalysisLukania BoazNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rime of The Ancient Mariner EssayDokument2 SeitenThe Rime of The Ancient Mariner EssayArthur FleckNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of WastelanddDokument12 SeitenSummary of Wastelanddfiza imranNoch keine Bewertungen

- The City of GodDokument16 SeitenThe City of GodJei Em MonteflorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lecture 01 Overview of Business AnalyticsDokument52 SeitenLecture 01 Overview of Business Analyticsclemen_angNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literary Criticism of Aristotle by Nasrullah Mambrol On May 1, 2017 - (0)Dokument7 SeitenLiterary Criticism of Aristotle by Nasrullah Mambrol On May 1, 2017 - (0)amnaarabiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle Concept of TragedyDokument3 SeitenAristotle Concept of TragedyNomy MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle: The PoeticsDokument13 SeitenAristotle: The PoeticsKanwal KhalidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revolt-Of-Satan-In-Paradise-Lost-Book-1-71585 - Rudrani DattaDokument7 SeitenRevolt-Of-Satan-In-Paradise-Lost-Book-1-71585 - Rudrani DattaRUDNoch keine Bewertungen

- Significance of The Bird Albatross in The Rime of The Ancient MarinerDokument3 SeitenSignificance of The Bird Albatross in The Rime of The Ancient Marinerشاكر محمود عبد فهدNoch keine Bewertungen

- Questions For MA English (Part 2)Dokument5 SeitenQuestions For MA English (Part 2)Muhammad Ali Saqib0% (1)

- Paradise Lost EssayDokument5 SeitenParadise Lost EssayJon Jensen100% (1)

- Ode To A NightingaleDokument3 SeitenOde To A NightingaleȘtefan Alexandru100% (1)

- 09 Shelley Defence of PoetryDokument5 Seiten09 Shelley Defence of PoetrysujayreddNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ancient Mariner and The Theme of SufferingDokument4 SeitenThe Ancient Mariner and The Theme of SufferingNabil Ahmed0% (1)

- A Critical Estimate of MiltonDokument3 SeitenA Critical Estimate of MiltonTANBIR RAHAMANNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tragedy NotesDokument3 SeitenTragedy NotesTyler Folkedahl100% (1)

- Sir Philip Sidney Enotes Summary of Sidney's Defence or Apology For PoetryDokument4 SeitenSir Philip Sidney Enotes Summary of Sidney's Defence or Apology For Poetrycjlass100% (2)

- Longinus: On The SublimeDokument2 SeitenLonginus: On The SublimeGenesis Aguilar100% (1)

- Tradition and The Individual Talent - ANALYSIS2Dokument8 SeitenTradition and The Individual Talent - ANALYSIS2Swarnav MisraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Problem of Satan in Miltons Paradise Lost PDFDokument107 SeitenThe Problem of Satan in Miltons Paradise Lost PDFسہاء قاضیNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hyperion Critical CommentsDokument9 SeitenHyperion Critical CommentsNoor UlainNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paradise Lost Book 1: ArgumentDokument2 SeitenParadise Lost Book 1: ArgumentMuhammad SaadNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Epic Features of The IliadDokument4 SeitenThe Epic Features of The IliadmimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle Poetics Paper PostedDokument9 SeitenAristotle Poetics Paper PostedCurtis Perry OttoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aristotle: The PoeticsDokument8 SeitenAristotle: The PoeticsrmosarlaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CatharsisDokument4 SeitenCatharsisjazib1200Noch keine Bewertungen

- Poetic Truth For Utopian and Fairy TaleDokument4 SeitenPoetic Truth For Utopian and Fairy TalejoecerfNoch keine Bewertungen

- PAST PAPERS CriticismDokument16 SeitenPAST PAPERS CriticismAR MalikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Samus Heany by Saqib JanjuaDokument7 SeitenSamus Heany by Saqib JanjuaMuhammad Ali SaqibNoch keine Bewertungen

- Donne CanonizationDokument3 SeitenDonne CanonizationMalakNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdoniasDokument7 SeitenAdoniasShirin AfrozNoch keine Bewertungen

- NISSIM EZEKIEL PoemsDokument7 SeitenNISSIM EZEKIEL PoemsAastha SuranaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Structure of Waiting For GodotDokument4 SeitenThe Structure of Waiting For GodotShefali Bansal100% (1)

- Paper 201 Term Paper DoneDokument8 SeitenPaper 201 Term Paper DoneTunku YayNoch keine Bewertungen

- "Life of Galileo" As An Epic Drama.Dokument2 Seiten"Life of Galileo" As An Epic Drama.Muhammad SufyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- KeatsDokument15 SeitenKeatsChristy Anne100% (1)

- Staff and Tablature-Treble Clef-4 Lines Music PaperDokument1 SeiteStaff and Tablature-Treble Clef-4 Lines Music PaperSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANALYSIS Barth, John Giles Goat Boy (1966) Analysis by 5 CriticsDokument10 SeitenANALYSIS Barth, John Giles Goat Boy (1966) Analysis by 5 CriticsSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joyce's Early AestheticDokument24 SeitenJoyce's Early AestheticSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- ANALYSIS Barth, John Giles Goat Boy (1966) Analysis by 5 CriticsDokument10 SeitenANALYSIS Barth, John Giles Goat Boy (1966) Analysis by 5 CriticsSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mark Scheme For Emma's Holiday Essat Wuthering HDokument24 SeitenMark Scheme For Emma's Holiday Essat Wuthering HSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aspects of Narrative ArticleDokument4 SeitenAspects of Narrative ArticleSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Themes: Themes Are The Fundamental and Often Universal Ideas Explored in A Literary WorkDokument4 SeitenThemes: Themes Are The Fundamental and Often Universal Ideas Explored in A Literary WorkSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

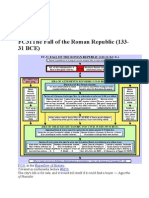

- FC31The Fall of The Roman RepublicDokument9 SeitenFC31The Fall of The Roman RepublicSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit f384 Classical Civilisation Greek Tragedy in Its Context Scheme of Work and Lesson Plan BookletDokument16 SeitenUnit f384 Classical Civilisation Greek Tragedy in Its Context Scheme of Work and Lesson Plan BookletSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chinese Poetry GuideDokument7 SeitenChinese Poetry GuideSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 JWP Kite Runner-LibreDokument13 Seiten1 JWP Kite Runner-LibreSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Eliot, Ulysses, Order, and MythDokument3 SeitenEliot, Ulysses, Order, and MythSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Madhouse Wall LibreDokument8 SeitenMadhouse Wall LibreSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medea Quick SummaryDokument1 SeiteMedea Quick SummarySamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The First Distinguishing Characteristics of BrowningDokument1 SeiteThe First Distinguishing Characteristics of BrowningSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Is TheatreDokument2 SeitenWhat Is TheatreSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 8 Narrative DevicesDokument1 SeiteChapter 8 Narrative DevicesSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Greek GlossaryDokument3 SeitenGreek GlossarySamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tragedy Fact SheetDokument1 SeiteTragedy Fact SheetSamBuckleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Rain HorseDokument3 SeitenThe Rain HorseSamBuckley100% (1)

- MCS 150 Page 1Dokument2 SeitenMCS 150 Page 1Galina NovahovaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leading A Multi-Generational Workforce:: An Employee Engagement & Coaching GuideDokument5 SeitenLeading A Multi-Generational Workforce:: An Employee Engagement & Coaching GuidekellyNoch keine Bewertungen

- SMM Live Project MICA (1) (1)Dokument8 SeitenSMM Live Project MICA (1) (1)Raj SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- MPLS Fundamentals - Forwardi..Dokument4 SeitenMPLS Fundamentals - Forwardi..Rafael Ricardo Rubiano PavíaNoch keine Bewertungen

- INA28x High-Accuracy, Wide Common-Mode Range, Bidirectional Current Shunt Monitors, Zero-Drift SeriesDokument37 SeitenINA28x High-Accuracy, Wide Common-Mode Range, Bidirectional Current Shunt Monitors, Zero-Drift SeriesrahulNoch keine Bewertungen

- King of Chess American English American English TeacherDokument6 SeitenKing of Chess American English American English TeacherJuliana FigueroaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit 4Dokument2 SeitenUnit 4Sweta YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vol. III (B) - FANSDokument8 SeitenVol. III (B) - FANSKhaled ELSaftawyNoch keine Bewertungen

- CTY1 Assessments Unit 6 Review Test 1Dokument5 SeitenCTY1 Assessments Unit 6 Review Test 1'Shanned Gonzalez Manzu'Noch keine Bewertungen

- Coffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee EverywhereDokument55 SeitenCoffee in 2018 The New Era of Coffee Everywherec3memoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Practice Quiz 5 Module 3 Financial MarketsDokument5 SeitenPractice Quiz 5 Module 3 Financial MarketsMuhire KevineNoch keine Bewertungen

- Keong Mas ENGDokument2 SeitenKeong Mas ENGRose Mutiara YanuarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fini Cat K-Max 45-90 enDokument16 SeitenFini Cat K-Max 45-90 enbujin.gym.essenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Teaching English in The Elementary Grades (Language Arts)Dokument21 SeitenTeaching English in The Elementary Grades (Language Arts)RENIEL PABONITANoch keine Bewertungen

- Orca Share Media1579045614947Dokument4 SeitenOrca Share Media1579045614947Teresa Marie Yap CorderoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hybrid and Derivative Securities: Learning GoalsDokument2 SeitenHybrid and Derivative Securities: Learning GoalsKristel SumabatNoch keine Bewertungen

- ColceruM-Designing With Plastic Gears and General Considerations of Plastic GearingDokument10 SeitenColceruM-Designing With Plastic Gears and General Considerations of Plastic GearingBalazs RaymondNoch keine Bewertungen

- MKTG4471Dokument9 SeitenMKTG4471Aditya SetyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Review - ChE ThermoDokument35 SeitenReview - ChE ThermoJerome JavierNoch keine Bewertungen

- B. Complete The Following Exercise With or Forms of The Indicated VerbsDokument4 SeitenB. Complete The Following Exercise With or Forms of The Indicated VerbsLelyLealGonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- CEO - CaninesDokument17 SeitenCEO - CaninesAlina EsanuNoch keine Bewertungen

- My Husband'S Family Relies On Him Too Much.... : Answered by Ustadha Zaynab Ansari, Sunnipath Academy TeacherDokument4 SeitenMy Husband'S Family Relies On Him Too Much.... : Answered by Ustadha Zaynab Ansari, Sunnipath Academy TeacherAlliyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals of Group DynamicsDokument12 SeitenFundamentals of Group DynamicsLimbasam PapaNoch keine Bewertungen