Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Marketing Deals With Identifying and Meeting Human and Social Needs

Hochgeladen von

Masa Claudiu MugurelCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Marketing Deals With Identifying and Meeting Human and Social Needs

Hochgeladen von

Masa Claudiu MugurelCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The marketing mix

The marketing mix is a set of controllable marketing tools that an institution uses to

produce the response it wants from its various target markets. It consists of everything

that the university can do to influence the demand for the services that it offers.

Tangible products have traditionally used a 4Ps model, the services sector on the other

hand uses a 7P approach in order to satisfy the needs of the service providers

customers: product, price, place, promotion, people, physical facilities and processes.

The product is what is being sold. It is more than a simple set of tangible features, it

is a complex bundle of benefits that satisfy customer needs. choice.

The price element of the services marketing mix is dominated by what is being

Charged

Place is the distribution method that the university adopts to provide the tuition to

its market in a manner that meets, if not exceeds, student expectations

Promotion encompasses all the tools that universities can use to provide the market

with information on its offerings: advertising, publicity, public relations and sales

promotional efforts.

The intangible nature of services resulted in the addition of a further element

people. The people element of the marketing mix includes all the staff of the university

that interact with prospective students and indeed once they are enrolled as students of

the university. These could be both academic, administrative and support staff.

in their range of options than an eminent Professors publications or research record.

Physical evidence and processes are the newest additions to the services mix.

Physical evidence is the tangible component of the service offering. A variety of

tangible aspects are evaluated by a universitys target markets, ranging from the

teaching materials to the appearance of the buildings and lecture facilities at the

university.

While processes are all the administrative and bureaucratic functions of the

university: from the handling of enquiries to registration, from course evaluation to

examinations, from result dissemination to graduation, to name but a few. Unlike

tangible products that a customer purchases, takes ownership of and then takes home

to consume, a university education requires payment prior to consumption, an

ownership exchange does not take place and a long and closer face-to-face the

relationship often results. Students attend classes for at least a year (on post-graduate

programmes) and much longer for undergraduate degrees. During the period that the

student is registered, processes need to be set in motion to ensure that the student

registers for the correct courses, has marks or grades correctly calculated and entered

against the students name and is ultimately awarded the correct qualification. While

this might seem quite straight forward, there are numerous other processes that need

to be implemented concurrently (with the finance system, accommodation, time tabling

and the library) to ensure the highest level of student satisfaction.

The 7P business school marketing mix

The names for the seven factors were intuitively developed, based on the

appropriateness of the label in representing the variables that were included in the

factor. Given that variables with the highest loadings in that factor are considered

more important, these had the greatest influence in the selection of the factor name. For

example, in this factor solution, the promotion factor was named this on the basis of

variables measuring advertising, publicity and electronic media communications being

included in the factor. While the price label came from the arrangements

A new higher education

marketing mix: the 7Ps for MBA

marketing

Jonathan Ivy

Birmingham City University, Birmingham, UK

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0951-354X.htm

for people

Behavioural economics and consumer behaviour in financial services

Loss aversion, prospect theory, the disposition effect and the endowment effect

Explanation. People have been shown to be loss averse, generally appearing to dislike

losing something roughly twice as much as they like gaining it (Kahneman et al., 1991;

Thaler and Sunstein, 2008). Such a phenomenon has been shown in a number of

experimental studies in a broad range of contexts (Tversky and Kahneman, 1991;

Benartzi and Thaler, 1995; Camerer et al., 1997). Loss aversion can be explained by

prospect theory (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979), which states that an individuals value

function (whether for money or otherwise) is concave for gains but convex for losses. In

other words, people are more sensitive to losses compared to gains of similar magnitude.

This is illustrated in Figure 1. The reference point in the diagram is the current position

of the individual concerned. Gains and losses are evaluated with reference to this neutral

reference point. The value function takes an asymmetric S-shape because marginal value

(or sensitivity) declines as absolute gains and losses increase in size.

Loss aversion and prospect theory are also related to the disposition effect, which

refers to the tendency of investors to continue holding assets that have dropped in

value and to sell assets that have increased in value (Kahneman et al., 1990). Also

closely related is the endowment effect, which is the tendency of individuals to place a

higher price or value on an object if they own it than if they do not. Put simply,

according to standard economic theory, what we are willing to pay for a good should

be equal to what we are willing to accept to be deprived of it. However, experimental

studies have shown that we generally demand more money to part with something

once we own it than we would be willing to pay for it in the first place (Knetsch, 1989;

Kahneman et al., 1990).

Behavioural economics and

financial services marketing:

a review

Swee-Hoon Chuah and James Devlin

Nottingham University Business School, Nottingham, UK

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0265-2323.htm

pentru evidenta fizica

technological change and the transformation of labour in the US insurance industry

Evoluia pieei de asigurri din SUA este legat de dezvoltarea i aplicarea

tehnologiilor create pentru a mbunti nregistrarea, procesarea, obinerea i

analiza datelor. Abilitatea de a capitaliza costurile cu fora de munc a reprezentat

un avantaj pentru firmele de asigurri de pe piaa american. De aceea, este

important s analizm impactul pe termen lung al birourilor tehnologizate i a

serviciilor de calcul i contabilitate computerizate. Achiziia i uzul tehnologiei

computerizate de ctre industria de asigurri a a avut origini att interne, ct i

externe. Firmele de asigurri nu numai c au achiziionat tehnologie de calcul

sofisticat, dar au i nvat cum s foloseasc i s modifice aceast tehnologie

pentru a-i dezvolta un avantaj competitiv pe pia. De asemenea, automatizarea

sarcinilor de rutin din industria asigurrilor a dus la costuri mai mici cu fora de

munc. Mainile care i fceau treaba repede i sigur au nlocuit funcionarii leni

i fr experien pentru a aduce beneficii n ceea ce privete costurile firmei.

Acest lucru a dus la *omajul tehnologic*, aa cum l-a numit Keynes, lipsa de

locuri de munc pentru oameni datorit mecanizrii activitii pe care unii o

ntreprindeau. Keynes era un cunosctor al domeniului cu multe studii la activ,

acest lucru i datorit statului su de preedinte i manager de investiii al unei

mari firme de asigurri din Marea Britanie.

Cambridge Journal of Economics 2001, nr. 25, pag. 517-537

Classical labour-displacing technological change : the case of the US insurance

industry Jason Hecht

Pentru produs

It appears to be the case that

foreign providers have failed to appreciate that the interest of many Chinese

consumers

in insurance or financial products is closely linked to investment and financial

management. This may partly account for the low market share (Ji and Thomas,

2001).

Analyzing efficiency in the

Chinese life insurance industry

Xiaoling Hu

Business School, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, UK

Cuizhen Zhang

Department of International Economics, Chinese Foreign Affairs University,

Beijing, Peoples Republic of China

Jin-Li Hu

Institute of Business and Management, National Chiao Tung University,

Taipei City, Taiwan, and

Nong Zhu

Institut National de la Recherche Scientifique,

Montreal, Canada

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/0140-9174.htm

pentru promovare

Reputaiile puternice ale corporaiilor rezult n mod clar dintr-un amestec al performanelor

actuale ale companiei pe pia i eforturile acestora de a dezvolta percepii pozitive n

legtur cu comportamentul lor ca afacere, atitudinea lor i valorile pe care le susin din

partea publicului-int. Este cunoscut faptul c o reputaie solid nu numai c reflect

calitatea, sigurana, aspectul, preul i distribuia produsului sau serviciului oferit, dar,

totodat, determin prile interesate s aib impresii de marketeri, impresii asupra pieei

i companiei care sunt caracterizate de competen i autoritate(Rhoads and Cialdini,

2002) i le produc acestora implicare n fenomen i n problemele ce in de

aspecte financiare, de mediu sau de comunitate. (Saiia and Cyphert, 2003).

Chiar dac exist o documentaie stufoas asupra a cum oamenii de marketing

promoveaz un produs, atributele acestuia i beneficiile pe care le aduce,

precum i sentimentul de bucurie ce va rezulta din cumprarea sau consumul

bunului sau serviciului promovat (Rossiter and Percy, 2001), exist prea puine

dovezi de cum companiile i ntreprinderile reflecteaz asupra a ce este

promovat i cum manageriaz aceste lucruri i identitatea corporaiei pentru a

construi sau a menine o reputaie puternic pe pia. (Pruzan, 2001).

This may be because, as Dowling (2001, p. 123) reminds us, stakeholders, and

especially customers, are more interested in what companies do for them than in

what they say about themselves. Nevertheless, the creation of trust in a

company, its expertise, solidity and good intentions is of particular importance if

the company specialises in intangible products or services that have become

almost synonymous with the company name. This is most obviously the case

with financial products and services offered by banks, insurance companies,

investment firms and a variety of consultancies from which purchases are

typically infrequent and long-term and often without immediate pay-offs or

gratification for the customer. Financial products and services are easily

perceived as generic and undifferentiated, and we would expect little inclination

among advert readers to try to process more than a minimum of technical

information in order to better understand and appreciate their complexity. On the

other hand, customers in this market are buying a high-involvement product

associated with financial risk and will be seeking some reassurance that the

service and its source are dependable.

Therefore, we assume that members of the industry will want to rely

considerably

more on corporate image advertising (whose main objective is to positively

describe

the advertiser) than on product advertising describing features of the financial

service

or the positive emotions that the customer will experience from purchasing or

consuming the service. In the current research, we have closely examined the

advertising of a number of international financial companies to determine what

they in

fact say about themselves to appear dependable, trustworthy and compassionate.

Building credibility

in international banking

and financial markets

A study of how corporate reputations are

managed through image advertising

Poul Erik Flyvholm Jrgensen

Aarhus School of Business, University of Aarhus, Aarhus, Denmark, and

Maria Isaksson

Norwegian School of Management BI, Oslo, Norway

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at

www.emeraldinsight.com/1356-3289.htm

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- QUESTION: With Relevant Examples, Explain The Product Development Stages. SolutionDokument11 SeitenQUESTION: With Relevant Examples, Explain The Product Development Stages. SolutionKisitu MosesNoch keine Bewertungen

- M.R.P. HarryDokument46 SeitenM.R.P. Harryjainalok28Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Thesis Dedication and AcknowledgementDokument5 SeitenSample Thesis Dedication and Acknowledgementrachelquintanaalbuquerque100% (2)

- Customer Value PDFDokument6 SeitenCustomer Value PDFsaajan shresthaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sample Thesis On Customer LoyaltyDokument4 SeitenSample Thesis On Customer Loyaltydwm7sa8p100% (2)

- CRM in The Insurance Industry: An Attempt To Use Survival Analysis in Retention and Cross SellingDokument10 SeitenCRM in The Insurance Industry: An Attempt To Use Survival Analysis in Retention and Cross SellingvprrvpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Organizational Customers' Retention Strategies On CustomerDokument10 SeitenOrganizational Customers' Retention Strategies On CustomerDon CM WanzalaNoch keine Bewertungen

- An OrganizationDokument7 SeitenAn OrganizationAlven BlancoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2 Customer Engagement As A New Perspective in Customer ManagementDokument7 Seiten2 Customer Engagement As A New Perspective in Customer ManagementOdnooMgmrNoch keine Bewertungen

- CRM-Unit IDokument40 SeitenCRM-Unit IOsamaMazhariNoch keine Bewertungen

- ConclusionDokument29 SeitenConclusionVarunMalhotra100% (1)

- Marketing:: Engaging in Marketing ActivityDokument4 SeitenMarketing:: Engaging in Marketing ActivityFaisal MasudNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fresnoza Edit 9-7-22Dokument40 SeitenFresnoza Edit 9-7-22Cdrink MidsayapNoch keine Bewertungen

- HutchDokument93 SeitenHutchShree MurtiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Marketing Mix Elements for ServicesDokument12 SeitenMarketing Mix Elements for Servicespratik bansyatNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Study On Scope of Service MarketingDokument8 SeitenA Study On Scope of Service MarketingNisarg DarjiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review On Relationship Marketing PDFDokument5 SeitenLiterature Review On Relationship Marketing PDFafmzxpqoizljqo100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction of Hutch UsersDokument93 SeitenCustomer Satisfaction of Hutch Userskunal hajareNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Lifetime Value Research in Marketing: A Review and Future DirectionsDokument13 SeitenCustomer Lifetime Value Research in Marketing: A Review and Future DirectionsYannick Vandewalle0% (1)

- Marketing Strategies for ServicesDokument4 SeitenMarketing Strategies for Servicesraji thanguNoch keine Bewertungen

- Information About 11 P'sDokument2 SeitenInformation About 11 P'sArish AdduriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On Service Quality in HotelsDokument4 SeitenThesis On Service Quality in Hotelskulilev0bod3100% (2)

- Value CreationDokument52 SeitenValue Creationresza swegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Topics On Customer SatisfactionDokument8 SeitenThesis Topics On Customer Satisfactionfjmzktm7100% (2)

- PHD Thesis On Customer LoyaltyDokument5 SeitenPHD Thesis On Customer Loyaltyjqcoplhld100% (2)

- Principles of Management or VBMDokument56 SeitenPrinciples of Management or VBMAftaab AhmedNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Relationship Marketing Process A Conceptualization and Application PDFDokument14 SeitenThe Relationship Marketing Process A Conceptualization and Application PDFkoreanguyNoch keine Bewertungen

- World Class Operations JUNE 2022Dokument10 SeitenWorld Class Operations JUNE 2022Rajni KumariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Principles of Management or VBMDokument56 SeitenPrinciples of Management or VBMdilip_bharadiyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Issue Diagnosis Memo DRAFT (Djenane Spence AndreDokument5 SeitenIssue Diagnosis Memo DRAFT (Djenane Spence Andrewilgens valmyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction in InsuranceDokument50 SeitenMeasuring Customer Satisfaction in InsuranceKavita Rani0% (1)

- Customer Relationship ManmagementDokument51 SeitenCustomer Relationship ManmagementmuneerppNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Satisfaction of Bajaj Allianz General InsuranceDokument50 SeitenCustomer Satisfaction of Bajaj Allianz General InsuranceSThandayuthapaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Financial Impact of CRM ProgrammesDokument15 SeitenThe Financial Impact of CRM ProgrammesPrabhu ReddyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Statement For Marketing PlanDokument6 SeitenThesis Statement For Marketing PlanKarla Long100% (2)

- Customer Loyalty Thesis PDFDokument8 SeitenCustomer Loyalty Thesis PDFPayingSomeoneToWriteAPaperJackson100% (2)

- Chapter - 1Dokument56 SeitenChapter - 1arunjoseph165240Noch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis On Recruitment and RetentionDokument4 SeitenThesis On Recruitment and RetentionMiranda Anderson100% (2)

- Customer Engagement Customer Engagement (CE) Refers To The Engagement of Customers With OneDokument8 SeitenCustomer Engagement Customer Engagement (CE) Refers To The Engagement of Customers With OneSangeetha JayakumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master Thesis Affiliate MarketingDokument4 SeitenMaster Thesis Affiliate Marketingjessicastapletonscottsdale100% (2)

- Balancing Acquisition and Retention Resources Maximizes ProfitsDokument0 SeitenBalancing Acquisition and Retention Resources Maximizes ProfitsVlad CosteaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Service Satisfaction ThesisDokument8 SeitenCustomer Service Satisfaction Thesisnicoledixonmobile100% (1)

- Innovation RelationshipDokument4 SeitenInnovation RelationshipxyqqflyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Services Marketing: Unit - 1 MaterialDokument37 SeitenServices Marketing: Unit - 1 Materiallaxmy4uNoch keine Bewertungen

- Online Shopping - Factors Influencing Consumer BehaviorDokument38 SeitenOnline Shopping - Factors Influencing Consumer BehaviorSittie Hana Diamla SaripNoch keine Bewertungen

- Master Thesis Public Administration UtwenteDokument8 SeitenMaster Thesis Public Administration Utwentekatrinaduartetulsa100% (1)

- A Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Samsung Mobile ServiceDokument56 SeitenA Study On Customer Satisfaction Towards Samsung Mobile ServiceAkilarun67% (6)

- Review of Literature On Consumer Brand PreferenceDokument5 SeitenReview of Literature On Consumer Brand PreferenceafduaciufNoch keine Bewertungen

- Modeling Customer Lifetime ValueDokument17 SeitenModeling Customer Lifetime ValueaggiesooyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction to Operations ManagementDokument5 SeitenIntroduction to Operations Managementdra_gonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Customer Loyalty Dissertation PDFDokument4 SeitenCustomer Loyalty Dissertation PDFPaperWritingHelpSingapore100% (1)

- Effective AdvertisingDokument9 SeitenEffective AdvertisingmaliksubemopNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7Ps Marketing Mix ExplainedDokument9 Seiten7Ps Marketing Mix ExplainedBashi Taizya100% (1)

- Customer Satisfaction of Bajaj Allianz General InsuranceDokument44 SeitenCustomer Satisfaction of Bajaj Allianz General InsuranceKusharg RohatgiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thesis Acknowledgement Sample SupervisorDokument6 SeitenThesis Acknowledgement Sample Supervisoranaespinalpaterson100% (2)

- Measuring Customer Satisfaction in InsuranceDokument57 SeitenMeasuring Customer Satisfaction in InsuranceRahul RayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Pricing Journey: The Organizational Transformation Toward Pricing ExcellenceVon EverandThe Pricing Journey: The Organizational Transformation Toward Pricing ExcellenceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Benchmarking for Businesses: Measure and improve your company's performanceVon EverandBenchmarking for Businesses: Measure and improve your company's performanceNoch keine Bewertungen

- Checklist - Optimizing Your YouTube ChannelDokument3 SeitenChecklist - Optimizing Your YouTube ChannelMasa Claudiu Mugurel100% (1)

- RPA Awareness Training Lesson 2Dokument8 SeitenRPA Awareness Training Lesson 2Masa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- RPADokument7 SeitenRPAAdinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Dokument8 SeitenThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- More Favorable Conditions For Business Creation and GrowthDokument2 SeitenMore Favorable Conditions For Business Creation and GrowthMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tabel 2 - Matricea Riscurilor in Functie de Impact Si Probabilitate (Ierarhia Riscurilor)Dokument3 SeitenTabel 2 - Matricea Riscurilor in Functie de Impact Si Probabilitate (Ierarhia Riscurilor)Masa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Dokument8 SeitenThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Dokument8 SeitenThe Syntax of Complex Sentence - Sentence Negation (Course 1)Corina Elena NiculaeNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Midsummer Night's DreamDokument42 SeitenA Midsummer Night's DreamMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Article The Literary Significance of The Catcher in The RyeDokument3 SeitenCritical Article The Literary Significance of The Catcher in The RyeMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Comparative Analysis of Private PensionsDokument14 SeitenA Comparative Analysis of Private PensionsMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Victorian Architecture TermsDokument1 SeiteVictorian Architecture TermsMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 Fundamental Concepts: Defining MarketingDokument9 Seiten1 Fundamental Concepts: Defining MarketingMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Res Essay IdeasDokument6 SeitenRes Essay IdeasMasa Claudiu MugurelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Types of ReliabilityDokument6 SeitenTypes of ReliabilityAbraxas LuchenkoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Agile Fundamentals Learning OutcomesDokument11 SeitenAgile Fundamentals Learning OutcomesGabriela Venegas100% (1)

- Memory Strategies and Education Protect Mental DeclineDokument7 SeitenMemory Strategies and Education Protect Mental DeclineHarsh Sheth60% (5)

- Cot English 4 1ST QuarterDokument5 SeitenCot English 4 1ST QuarterJessa S. Delica IINoch keine Bewertungen

- Home - Eastern Pulaski Community School CorporatiDokument1 SeiteHome - Eastern Pulaski Community School CorporatijeremydiltsNoch keine Bewertungen

- ElectroscopeDokument3 SeitenElectroscopeRobelle Grace M. CulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EQ Mastery Sept2016Dokument3 SeitenEQ Mastery Sept2016Raymond Au YongNoch keine Bewertungen

- John Paul PeraltaDokument5 SeitenJohn Paul PeraltaAndrea Joyce AngelesNoch keine Bewertungen

- RA Criminologists Davao June2019 PDFDokument102 SeitenRA Criminologists Davao June2019 PDFPhilBoardResultsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Vitae: Y N Email ObjectiveDokument2 SeitenCurriculum Vitae: Y N Email ObjectiveCatherine NippsNoch keine Bewertungen

- CV Engineer Nizar Chiboub 2023Dokument5 SeitenCV Engineer Nizar Chiboub 2023Nizar ChiboubNoch keine Bewertungen

- Personal Growth-Building HabitsDokument3 SeitenPersonal Growth-Building HabitsMr. QuitNoch keine Bewertungen

- TECHNOLOGY ENABLED COMMUNICATION TOOLSDokument15 SeitenTECHNOLOGY ENABLED COMMUNICATION TOOLSzahari99100% (1)

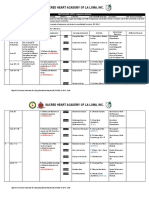

- Curriculum Map Grade 10 2019 2020Dokument15 SeitenCurriculum Map Grade 10 2019 2020Sacred Heart Academy of La Loma100% (1)

- Chapter 3Dokument9 SeitenChapter 3Riza PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Motivational Interviewing in Preventing Early Childhood Caries in Primary Healthcare: A Community-Based Randomized Cluster TrialDokument6 SeitenMotivational Interviewing in Preventing Early Childhood Caries in Primary Healthcare: A Community-Based Randomized Cluster TrialRahmatul SakinahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Interprofessional Health Care TeamsDokument3 SeitenInterprofessional Health Care TeamsLidya MaryaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- D1, L2 Sorting AlgorithmsDokument17 SeitenD1, L2 Sorting AlgorithmsmokhtarppgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annoying Classroom DistractionsDokument11 SeitenAnnoying Classroom DistractionsGm SydNoch keine Bewertungen

- Task-Based Speaking ActivitiesDokument11 SeitenTask-Based Speaking ActivitiesJaypee de GuzmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pengawasan Mempengaruhi Disiplin Kerja Karyawan KoperasiDokument6 SeitenPengawasan Mempengaruhi Disiplin Kerja Karyawan KoperasiIrvan saputraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ACTG 381 Syllabus (Fall 2019) Elena Redko Portland State University Intermediate Financial Accounting and Reporting IDokument11 SeitenACTG 381 Syllabus (Fall 2019) Elena Redko Portland State University Intermediate Financial Accounting and Reporting IHardly0% (1)

- Corus Case StudyDokument4 SeitenCorus Case StudyRobert CriggerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Resume Seminar Nasional "Ilmota International Conference Digital Transformation Society 5.0"Dokument7 SeitenResume Seminar Nasional "Ilmota International Conference Digital Transformation Society 5.0"aris trias tyantoroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Education, Summer Camps and Programs - 0215WKTDokument10 SeitenEducation, Summer Camps and Programs - 0215WKTtimesnewspapersNoch keine Bewertungen

- HyponymyDokument3 SeitenHyponymysankyuuuuNoch keine Bewertungen

- SOP Bain Vishesh Sharma PDFDokument1 SeiteSOP Bain Vishesh Sharma PDFNikhil JaiswalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nursing Leadership Practice QuestionsDokument15 SeitenNursing Leadership Practice QuestionsNneka Adaeze Anyanwu0% (2)

- Critical Approach To ReadingDokument29 SeitenCritical Approach To ReadingRovince CarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colab Participation Documentary and RationaleDokument1 SeiteColab Participation Documentary and RationaleAntonio LoscialeNoch keine Bewertungen