Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Influencia Tenis

Hochgeladen von

Paco Parra Plaza0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

22 Ansichten9 SeitenFew data exist on the long-term adaptations to heavy resistance training in women. This study examined the effect of volume of resistance exercise on the development of physical performance abilities in competitive, collegiate women tennis players. No significant changes in body mass were observed in any of the groups throughout the entire training period.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

influencia_tenis

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenFew data exist on the long-term adaptations to heavy resistance training in women. This study examined the effect of volume of resistance exercise on the development of physical performance abilities in competitive, collegiate women tennis players. No significant changes in body mass were observed in any of the groups throughout the entire training period.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

22 Ansichten9 SeitenInfluencia Tenis

Hochgeladen von

Paco Parra PlazaFew data exist on the long-term adaptations to heavy resistance training in women. This study examined the effect of volume of resistance exercise on the development of physical performance abilities in competitive, collegiate women tennis players. No significant changes in body mass were observed in any of the groups throughout the entire training period.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 9

http://ajs.sagepub.

com/

Medicine

The American Journal of Sports

http://ajs.sagepub.com/content/28/5/626

The online version of this article can be found at:

2000 28: 626 Am J Sports Med

James M. Lynch and Steven J. Fleck

William J. Kraemer, Nicholas Ratamess, Andrew C. Fry, Travis Triplett-McBride, L. Perry Koziris, Jeffrey A. Bauer,

Adaptations in Collegiate Women Tennis Players

Influence of Resistance Training Volume and Periodization on Physiological and Performance

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine

can be found at: The American Journal of Sports Medicine Additional services and information for

http://ajs.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://ajs.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

What is This?

- Sep 1, 2000 Version of Record >>

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Influence of Resistance Training Volume

and Periodization on Physiological and

Performance Adaptations in Collegiate

Women Tennis Players

William J. Kraemer,* PhD, Nicholas Ratamess,* MS, Andrew C. Fry, PhD,

Travis Triplett-McBride, PhD, L. Perry Koziris, PhD, Jeffrey A. Bauer, PhD,

James M. Lynch, MD, and Steven J. Fleck, PhD

From the Laboratory for Sports Medicine, The Pennsylvania State University, University

Park, Pennsylvania, *The Human Performance Laboratory, Ball State University, Muncie,

Indiana, and the Department of Sport Science, Colorado College, Colorado Springs, Colorado

ABSTRACT

Few data exist on the long-term adaptations to heavy

resistance training in women. The purpose of this in-

vestigation was to examine the effect of volume of

resistance exercise on the development of physical

performance abilities in competitive, collegiate

women tennis players. Twenty-four tennis players

were matched for tennis ability and randomly placed

into one of three groups: a no resistance exercise

control group, a periodized multiple-set resistance

training group, or a single-set circuit resistance training

group. No significant changes in body mass were ob-

served in any of the groups throughout the entire train-

ing period. However, significant increases in fat-free

mass and decreases in percent body fat were ob-

served in the periodized training group after 4, 6, and 9

months of training. A significant increase in power

output was observed after 9 months of training in the

periodized training group only. One-repetition maxi-

mum strength for the bench press, free-weight shoul-

der press, and leg press increased significantly after 4,

6, and 9 months of training in the periodized training

group, whereas the single-set circuit group increased

only after 4 months of training. Significant increases in

serve velocity were observed after 4 and 9 months of

training in the periodized training group, whereas no

significant changes were observed in the single-set

circuit group. These data demonstrate that sport-spe-

cific resistance training using a periodized multiple-set

training method is superior to low-volume single-set

resistance exercise protocols in the development of

physical abilities in competitive, collegiate women ten-

nis players.

Resistance training is one of the primary conditioning

modalities that has been shown to be effective in mediat-

ing neuromuscular adaptations important for injury pre-

vention and improved sport performance.

1113, 32

How-

ever, few studies have examined long-term training

programs (that is, 6 months or greater), especially in wom-

en.

37, 38

With the increasing time demands placed on com-

petitive intercollegiate athletes due to National Collegiate

Athletic Association (NCAA) restrictions on the amount of

time allowed for supervised strength and conditioning

during both the in- and off-season programs, low-volume

training sessions may reduce training time. However, the

efficacy of low-volume heavy-resistance circuit training

protocols remains unclear in women athletes.

7

These low-volume programs have been characterized by

the use of a single set for a group of exercises. The single-

set system is one of the oldest systems, dating back to

1925 when first described by Liederman.

23

With the use of

such a training system, increases in strength have been

observed over short-term periods (for example, 7 to 14

weeks) that are comparable with those of high-volume mul-

tiple-set programs in untrained subjects.

4, 15, 24, 29, 31, 34, 36

However, such studies have not typically compared such

low-volume programs with a properly periodized resis-

tance training program over a long-term training period.

Address correspondence and reprint requests to William J. Kraemer,

PhD, The Human Performance Laboratory, Ball State University, Muncie, IN

47306.

No author or related institution has received any financial benefit from

research in this study. See Acknowledgments for funding information.

0363-5465/100/2828-0626$02.00/0

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE, Vol. 28, No. 5

2000 American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine

626

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

A recent study demonstrated no significant differences in

isometric torque values for knee extension and flexion at

different joint angles after 14 weeks of training with ei-

ther one or three sets of dynamic strength training in

untrained men and women.

36

However, the effect of using

such a training system in younger athletes over a longer

period of training (for example, an entire academic year)

remains unknown. Other studies in men have demon-

strated that the use of high-volume multiple-set systems

may result in superior strength gains in both untrained

subjects

1, 3, 33, 39, 41

and resistance-trained athletes.

16, 17

In

addition, most athletes using multiple-set protocols now

periodize their training to avoid overtraining, eliminate

boredom in the training routine, and optimize recovery,

which is of great importance in improving performance

and reducing the risk of injury.

17, 40, 42

Understanding the effects of using periodized resistance

training protocols with athletes may provide insights for

enhancing performance and preventing injury. The pri-

mary purpose of this study was to compare a high-volume,

periodized, multiple-set strength training program to a

low-volume, heavy-resistance circuit program over 9

months of training in competitive women tennis players.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Design and Approach to the Question

In this study a prospective, longitudinal study was under-

taken to examine the effect of exercise volume on the

physical performance of highly skilled tennis players. A

control group and two training cohorts were used to ex-

amine this question over the course of 9 months of train-

ing and tennis competition. This approach allowed us to

directly control and carefully monitor the training and

status of each subject in the study to gain insights into

this exercise prescription question. The context of the data

can be generalized only to the type of population examined

in the world of competitive tennis.

Subjects

Twenty-four collegiate women tennis players were

matched for tennis ability (that is, years of play, compet-

itive level, and United States Tennis Association [USTA]

ranking) and randomly placed into one of three groups. All

groups participated in all activities associated with com-

petitive collegiate tennis over 9 months, but the control

group (N 8) participated in no resistance training, the

periodized training group (N 8) participated in a peri-

odized resistance training program, and the single-set

group (N 8) participated in a single-set circuit resis-

tance training program. No significant differences were

observed between the subject characteristics at the onset

of the study (Table 1). Subjects reported a mean of 7.8

2.4 years of tennis experience with no differences between

groups. Each of the subjects was informed of the benefits

and risks of the investigation and subsequently signed an

approved consent form in accordance with the guidelines

of the university Institutional Review Board for use of

human subjects. All subjects were medically screened be-

fore the investigation and none had any medical or ortho-

paedic problems that would compromise her participation

and performance in the study. In addition, none of the

subjects were taking any medications that would confound

the data during this study.

Testing Protocols

All tests were performed at the same time of day for each

subject to reduce the effect of any diurnal variations. Sub-

jects were instructed to keep similar dietary and activity

profiles for each testing phase by keeping a diary. In

addition, subjects were instructed to refrain from exercise

for 24 hours before testing and to refrain from eating

within 6 hours of testing. Water was allowed ad libitum.

Actual experimental testing after preliminary familiariza-

tion and test-retest evaluations was performed on four

occasions: in August (pretraining), December (4 months),

February (6 months), and May (9 months) for all groups.

All subjects were carefully familiarized with all testing

and training protocols and procedures before initiation of

the study. The importance of removing the random learn-

ing effects in strength training studies has been verified

by Dudley et al.

6

and, thus, we tried to eliminate the

influence of acute learning effects on the absolute magni-

tude of changes in the test variables. A familiarization

period (consisting of at least three sessions) that included

instruction on proper technique was used for all testing

procedures.

6

Body Composition. Body composition was estimated us-

ing three skinfold measurements obtained with a Lange

skinfold caliper (Country Technology, Gays Mills, Wiscon-

sin) according to the methods described by Jackson et al.

14

The three sites consisted of the triceps, suprailiac, and

thigh. Percent body fat was estimated using the equation

of Siri.

35

The same investigators performed all tests. Body

mass was measured on a calibrated physicians scale.

Anaerobic Power. A Wingate cycle ergometer test proto-

col was used to determine peak power output for each

subject. Subjects were seated on a Monark cycle ergometer

(Recreation Equipment Unlimited, Inc., Pittsburgh, Penn-

sylvania) with the seat adjusted to a corresponding knee

angle of approximately 10 when one leg was in the ex-

tended position. A 2-minute warm-up was allowed using

minimal or no resistance. The ergometer load setting was

determined by the product of the subjects body weight

TABLE 1

Descriptive Characteristics for the Three Study Groups

(Means SD)

Characteristic

Group

Control

Periodized

training

Single-set

training

Age (years) 19.8 1.7 19.0 0.9 18.9 1.2

Height (cm) 167 5.1 168 4.2 167.5 5.2

Body mass (kg) 58.9 7.8 60.4 7.6 60.8 7.7

Vol. 28, No. 5, 2000 Volume Effects on Resistance Training for Women Tennis Players 627

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

and a factor of 0.075. Load was applied to the ergometer

after subjects attained the fastest possible pedaling rate.

Each subject maintained her maximal pedaling rate

throughout the 30-second test. Pedal revolutions were dig-

itally determined via a sensor on the flywheel interfaced

to a computer throughout the 30-second test and recorded

at each 5-second period. Power values were then calcu-

lated according to previously established methods.

21

Maximal counter-movement vertical jump height was

determined using a Vertec measurement device (Sports

Imports, Columbus, Ohio). Each subject was allowed one

practice trial, rested, and then was given three trials with

approximately 2 to 3 minutes of rest between trials. The

highest jump was recorded for analysis. Each score was

measured as the difference between the jump height and

the standing vertical reach of the subject on the Vertec

system.

Dynamic Muscular Strength Assessments. One-repeti-

tion maximum strength was determined for the seated

machine leg press, the free-weight shoulder press, and the

bench press exercises according to methods previously

described by Kraemer and Fry.

19

A warm-up set of 5 to 10

repetitions was performed using 40% to 60% of the per-

ceived maximum strength. After a 1-minute rest period, a

set of 3 to 5 repetitions was performed at 60%to 80%of the

perceived one-repetition maximum strength. Subse-

quently, 3 to 4 maximal trials (one-repetition sets) were

performed to determine the one-repetition maximum

strength. Rest periods between trials were 3 to 5 minutes.

A complete range of motion and proper technique were

required for each successful trial.

Maximal Serve Velocity. The methods used to analyze

the serve velocity have been previously described in de-

tail.

22

Two Panasonic 60 Hz model AG-450 video cameras

(Panasonic, Tokyo, Japan) were positioned facing each

other along the baseline of the testing court. Each camera

filmed all serves, producing a front and back view of all

the subjects. After a warm-up period, each subject was

instructed to hit the ball as hard as possible until 10

acceptable serves were filmed. An acceptable shot was

accomplished by hitting a ball into the deuce court for

right-handed players and into the ad court for left-handed

players. Ball velocity was determined by digitizing trials

and frame-by-frame analysis with the Peak Performance

2-D Motion Analysis system (Peak Performance Technol-

ogies, Englewood, Colorado). The data were expanded to

represent collection at 240 Hz using a cubic spline inter-

polation routine with no smoothing. Both displacement

and flight time of the ball were determined and were used

to calculate the velocity. Flight time of the ball was de-

fined as the time frame between immediate (approximate-

ly 17 msec) contact with the racket and contact within the

service box during the digitized trials. The mean of the top

three trial velocities for the serves was used for analysis

as this gave the highest test-retest reliability.

Training Programs

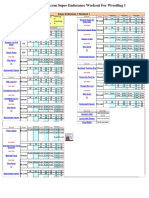

The resistance training protocols are overviewed in Table

2. Both groups trained 2 to 3 days per week depending on

match schedules for 9 months (totaling 100 workouts,

100% compliance). Training started in September and was

completed in May. Both resistance training groups per-

formed the same exercises (Table 2). The resistance used

for each exercise was based on the ability of the individual

athlete. The athlete adjusted the resistance for a given

exercise to allow only the set number of repetitions to be

performed. The single-set group used an 8 to 10 repetition

loading protocol for one set, whereas the periodized train-

ing group rotated each workout using either 4 to 6 repe-

titions (heavy resistance), 8 to 10 repetitions (moderate

resistance), or 12 to 15 repetitions (light resistance) for 2

to 4 sets of each exercise. This nonlinear periodization

program was designed to permit variation of both inten-

sity and volume, which is more practical for a sport like

tennis where match play and practice are year-round. In

addition, this model is specific for the sport of tennis and

conducive to the type of time constraints placed on the

tennis player over the course of a year (in-season and

off-season). All workouts were completed within 90 min-

utes or less, with the single-set circuit being shorter in

duration than the periodized program. Each workout was

individually supervised and workouts were recorded for

both resistance training groups. The control group took

part in all of the tennis-specific training and conditioning

drills but did not participate in the resistance training

segment of this investigation.

Statistical Analyses

The statistical evaluation of the data were accomplished

with an analysis of variance (3 groups by 4 time points)

with repeated measures. When appropriate, Tukeys post

hoc tests were used for pairwise comparisons. The subjects

TABLE 2

Resistance Training Exercise Protocols

Resistance:

Single-Set Circuit: 8 to 10 repetition maximum for all

exercises.

Periodized: Resistances were varied within a week between 4

to 6, 8 to 10, and 12 to 15 repetition maximum for the

exercises marked with an asterisk. All other exercises used

a constant resistance of 8 to 10. Number of sets varied

from 2 to 4.

Rest Periods

1 to 2 minutes for 12 to 15 and 8 to 10 repetition

maximum resistance, and 2 to 3 minutes for 4 to 6

repetition maximum resistance.

Resistance Exercises

Leg press (machine)

Bench press (barbells)

Single leg curls (machine)

Bent-over-rows (dumbbell)

Dumbbell lunge (dumbbell)

Split squats (barbell)

Military press (barbell)

Single knee extensions (machine)

Front pull downs (machine)

Back extensions (dumbbell)

Internal/external rotations (dumbbell)

Sit-ups/crunches

Hip tucks

Wrist extension/curls/hammers (dumbbell)

628 Kraemer et al. American Journal of Sports Medicine

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

were familiarized with each test over a 2-week period and

repeat testing established a baseline. This was followed by

two separate testing times where the same test was ad-

ministered under the same conditions with the same in-

vestigators or technicians who would perform the tests in

the study. This resulted in test-retest reliability of the

measures to demonstrate good stability in the measures

with intraclass correlation coefficients of r 0.95. The

control group was used to examine the stability of the

measures over time. Nevertheless, in calculating intra-

class correlations in the control group the r values were

0.90, again showing solid stability over time in the de-

pendent measures. Prior work also demonstrated a good

test-retest reliability for the measures used.

22

Using the

nQuery Advisor software (Statistical Solutions, Saugus,

Massachusetts), we found the statistical power for the n

size used ranged from 0.79 to 0.92. Statistical significance

was chosen as P 0.05.

RESULTS

The results for this study are presented in the subsequent

sections. Compliance for this study was 100% for all sub-

jects who were placed into a resistance training group.

Therefore, all women in the single-set and periodized

training groups completed 100 workouts.

Anthropometrics

No significant differences in body mass from pretraining

values were observed in any group over the 9-month train-

ing/competition period. However, significant increases in

fat-free mass and decreases in percent body fat were ob-

served in the periodized training group at 4, 6, and 9

months (percent body fat data are shown in Fig. 1). No

significant differences were observed in either the single-

set or the control groups.

Anaerobic Power

Changes in the peak power for the Wingate cycle ergome-

ter power test are shown in Figure 2A. A significant in-

crease in power output was observed at 9 months for the

periodized training group. No significant differences were

observed for the single-set or control groups. Changes in

the counter-movement vertical jump height are presented

in Figure 2B. Significant increases above pretraining val-

ues were observed at 4, 6, and 9 months for the periodized

training group. No significant differences were observed

for the single-set or control groups at any time point.

Dynamic Muscular Strength

Changes in one-repetition maximum strength for the

bench press, free-weight shoulder press, and leg press can

be seen in Figure 3. The periodized training group signif-

Figure 1. The effects of low-volume and high-volume, peri-

odized resistance training on percent body fat. *, significant

decrease from pretraining. @, significant decrease from pre-

training, 4 months, and 6 months. Significant decreases were

observed only in the periodized training group. P, periodized

training group; SSC, single-set circuit group; Con, control

group.

Figure 2. The effects of low-volume and high-volume, peri-

odized resistance training on muscular power. Panel A indi-

cates differences in the Wingate anaerobic power perfor-

mance test. Panel B indicates differences in vertical jump

performance. *, significant increase from pretraining. @, sig-

nificant increase from pretraining, 4 months, and 6 months.

Significant increases were observed only for the periodized

training group. See the legend at Figure 1 for abbreviations.

Vol. 28, No. 5, 2000 Volume Effects on Resistance Training for Women Tennis Players 629

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

icantly increased their one-repetition maximum strength

at 4, 6, and 9 months for all of the exercises. The single-set

group significantly increased strength only at 4 months

for all exercises. No further changes were observed beyond

this point. No difference in strength for any exercise was

observed in the control group.

Serve Velocity

Changes in serve velocity are shown in Figure 4. A signif-

icant increase above pretraining values in serve velocity

was observed at 4, 6 and 9 months in the periodized

training group. No significant changes were observed in

either the single-set or control groups.

DISCUSSION

Few data exist concerning the long-term resistance train-

ing adaptations in women.

37

The primary findings of this

investigation were that a high-volume, periodized, multi-

ple-set resistance training program elicited superior

1) increases in upper and lower body maximal strength,

2) increases in muscular power, 3) increases in lean body

mass, 4) decreases in percent body fat, and 5) increases in

tennis serve velocity when compared with a low-volume,

single-set circuit program in competitive collegiate women

tennis players during 9 months of training. A secondary

finding of interest was that both groups increased muscu-

lar strength during the first 4 months of training, but only

the periodized training group continued to improve signif-

icantly beyond this point. Of particular importance for

women tennis players was the finding that the periodized

training group was the only group to see sport-specific

changes in the maximal ball velocity in the tennis serve.

These findings may significantly affect program design

and long-term prescription of resistance training pro-

grams for women tennis players. It appears that a volume

of exercise threshold may be vital for some parameters to

continue to change over time and be integrated within the

athletes physiologic profile as it relates to performance.

Our data demonstrated a distinct difference in the pro-

gression of maximal strength over the 9-month training

period. The group undergoing periodized training had a

significantly different pattern of change when compared

with the low-volume single-set group after the first 4

months. Our data indicate that program differentiation

may take longer than a few months in women tennis

players because of the rapid increases observed in the

early phase of training (that is, first several months) to

almost any overload.

37, 38

Such separation may be very

volume-specific. Direct comparisons of single- and multi-

Figure 3. The effects of low-volume and high-volume, peri-

odized resistance training on muscular strength. Panel A

indicates differences in bench press. Panel B indicates dif-

ferences in free-weight shoulder press. Panel C indicates

differences in leg press. *, significant increase from pretrain-

ing. #, significant increase from pretraining and 4 months. @,

significant increase from pretraining, 4 months, and 6

months. See the legend at Figure 1 for abbreviations.

Figure 4. The effects of low-volume and high-volume, peri-

odized resistance training on tennis serve velocity. *, signif-

icant increase from pretraining. #, significant increase from

pretraining and 4 months. A significant increase was ob-

served only in the periodized training group. See the legend

at Figure 1 for abbreviations.

630 Kraemer et al. American Journal of Sports Medicine

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

ple-set protocols have produced conflicting results. Sev-

eral studies have reported superior increases in maximal

strength and vertical jump performance when multiple-

set protocols were used with untrained subjects.

1, 3, 33, 39, 41

In addition, the increases observed in groups who trained

with multiple sets were significantly greater when vol-

ume and intensity were periodized.

33, 41

In contrast,

several studies have reported similar strength increases

using both single- and multiple-set protocols in un-

trained subjects.

3, 4, 15, 24, 29, 31, 34, 36

To date, no study

has reported superior performance enhancement using

single-set programs in untrained or trained subjects.

However, from a practical perspective not all exercises

have to be performed for the same number of sets, and

thus the key factor appears to be the volume of exercise

performed for a given joints musculature as the number

of sets only contributes to that volume equation (sets

repetitions intensity).

Limited data are available comparing single- and mul-

tiple-set programs in athletes. The results of the present

study support previous findings in trained men where

high-volume, periodized, multiple-set resistance training

programs were superior to low-volume, single-set pro-

grams for increasing muscular strength

16, 17

and fat-free

mass.

17

In the present study, muscular strength increased

significantly in both groups during the first 4 months of

training. However, only the periodized training group

showed further improvement beyond this point. These

findings have direct implications for resistance training

exercise prescription oriented toward long-term progres-

sion in training tennis players with the goal of improve-

ment in these parameters. Kraemer

17

reported greater

increases in muscular strength, power, endurance, and

lean body mass when multiple-set programs were used in

collegiate football players versus nonperiodized low-vol-

ume programs. Kramer et al.

16

reported significantly

greater increases in one-repetition maximum squat using

multiple-set programs in resistance-trained college men.

In contrast, Ostrowski et al.

28

reported no significant dif-

ferences in maximal strength between training with ei-

ther one, two, or four sets per exercise in moderately

trained men. Considering that continued improvement in

weight training becomes more difficult with experience,

10

it appears that multiple-set, high-volume resistance exer-

cise protocols are most effective for long-term performance

enhancement in athletes. These findings may also support

the use of greater time commitments for resistance train-

ing in athletes.

Our data demonstrate limited transfer of the training to

power and maximal ball velocity in the tennis serve with

the single-set circuit program. Previously, Kraemer

17

also

reported limited improvements in various muscular per-

formance variables between the 3rd and 6th months of

training using a single-set program in football players.

This may have been due to either a lack of variation in

program design

16, 17, 40

or inadequate volume needed to

produce further increases that transfer to the skills be-

yond that of the initial adaptations.

16, 17

It could also be

due to the speed of movement used in the exercise. Mul-

tiple-set periodized programs have demonstrated superior

long-term performance improvements compared with sin-

gle-set

17, 33

and nonperiodized multiple-set programs.

42

Therefore, these data demonstrate that short-term im-

provements in muscular strength may be attained with

either single- or multiple-set programs during the first

few months. However, periodized multiple-set programs

are superior for transfer specificity in the carryover to

long-term performance enhancements of multiple-joint,

whole-body, closed kinetic chain activities in women ten-

nis athletes.

Fat-free mass increased significantly at 4, 6, and 9

months for the periodized training group, but no changes

were observed for the single-set group. Kraemer

17

re-

ported similar results in football players who trained with

either a single-set or periodized multiple-set training pro-

gram. Muscular hypertrophy in women, as a result of

resistance training, has been reported in previous stud-

ies.

37, 38

These studies used multiple-set programs during

resistance training. Limited data exist examining differ-

ences in fat-free mass resulting from single- versus mul-

tiple-set training in women. A possible explanation is al-

terations in hormonal concentrations conducive to

anabolism. Acute increases in growth hormone have been

reported during high-volume resistance exercise.

18, 20

In

particular, multiple-set programs were shown to be supe-

rior for rapid increases in growth hormone and decreases

in cortisol in women.

26

Therefore, it appears that the

volume of resistance exercise may be significant for hor-

monal alterations and, consequently, increases in fat-free

mass in women.

A significant difference between groups was also ob-

served for lower-body power. The periodized training

group significantly increased in the nonspecific Wingate

power output test at 9 months and in vertical jump height

at 4, 6, and 9 months, whereas no significant differences

were observed for the single-set group for either anaerobic

power test. Part of this variance may be accounted for by

total training volume. Kraemer

17

and Stone et al.

39

re-

ported significantly greater increases in muscular power

and vertical jump performance when high-volume, multi-

ple-set programs were used. Sanborn et al.

33

reported an

11% increase in vertical jump after 8 weeks of training

with multiple sets compared with a 0.3% increase ob-

served in a single-set group. Interestingly, Ostrowski et

al.

28

reported an insignificant decrease for the vertical

jump after 10 weeks of single-set training. In addition, a

large percentage of this variance may be accounted for by

repetition velocity. The periodized training group per-

formed their repetitions with moderate-to-explosive mus-

cle actions and velocities whereas the single-set group

performed each repetition in a slow, controlled manner.

Proponents of low-volume training typically prescribe one

set of 8 to 12 repetitions performed to momentary muscu-

lar failure at a slow velocity for predominantly single-joint

exercises.

29, 36

Thus, the single-set group performed each

repetition in accordance with this training approach. It

has been reported that fast contraction velocities are most

effective for increasing muscular power.

5, 25, 27

Therefore,

training solely with slow movements may have limited

power development in the single-set group, but explosive

Vol. 28, No. 5, 2000 Volume Effects on Resistance Training for Women Tennis Players 631

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

lifting is typically not supported by low-volume training

theories.

Perhaps the most significant finding was that the peri-

odized training group significantly increased their serve

velocity at 4 and 9 months, whereas the single-set group

showed no significant changes. The women who partici-

pated in this study were competitive collegiate tennis

players matched for tennis playing ability. Tennis is a

physiologically demanding sport

2

that requires power,

speed, balance, agility, coordination, flexibility, and car-

diovascular endurance.

8, 9, 30

Thus, increasing tennis-spe-

cific fitness components beyond typical tennis practice

gains was the goal of the resistance training program.

Both upper and lower body power are essential compo-

nents of tennis.

8

Testing maximal serve velocity was used

as an indicator variable for the efficacy of the training

programs on tennis performance ability. Therefore, the

periodized, multiple-set resistance training program was

most effective for increasing aspects of tennis performance

above pretraining values at 4, 6, and 9 months. It appears

a threshold of volume is needed to affect performance

changes. This has obvious value to tennis players and

coaches. Furthermore, these gains were maintained over

the duration of the study through a competitive tennis

season.

In summary, a higher-volume, periodized, multiple-set

resistance training program produced superior increases

in muscular strength, power, lean body mass, tennis per-

formance (as measured maximal serve velocity), and pro-

duced a superior decrease in percent body fat over a

9-month training period. A finding of interest was that

only the periodized training group showed continued im-

provement beyond that of the initial 4 months of training.

These findings have direct implications for program de-

sign for collegiate women tennis players where training

goals are related to long-term continued improvement in

such training variables. Based on our data, it appears that

periodized, multiple-set, resistance training programs are

most effective for long-term performance increases in

these collegiate athletes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported in part by a grant from United

States Tennis Association, Key Biscayne, Florida. We

thank all of the athletes and coaches who supported this

sport science project. In addition, we thank all of the

laboratory staff and trainers who helped with the testing

and training of these subjects and Coach Sue Whiteside

for her support.

REFERENCES

1. Berger R: Comparative effects of three weight training programs. Res Q

34: 396398, 1963

2. Bergeron MF, Maresh CM, Kraemer WJ, et al: Tennis: A physiological

profile during match play. Int J Sports Med 12: 474479, 1991

3. Capen EK: Study of four programs of heavy resistance exercises for

development of muscular strength. Res Q 27: 132142, 1956

4. Coleman AE: Nautilus vs Universal gym strength training in adult males.

Am Correct Ther J 31: 103107, 1977

5. Coyle EF, Feiring DC, Rotkis TC, et al: Specificity of power improvements

through slow and fast isokinetic training. J Appl Physiol 51: 14371442,

1981

6. Dudley GA, Tesch PA, Miller BJ, et al: Importance of eccentric actions in

performance adaptations to resistance training. Aviat Space Environ Med

62: 543550, 1991

7. Fleck SJ, Kraemer WJ: Designing Resistance Training Programs. Second

edition. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics, 1997

8. Groppel JL, Roetert EP: Applied physiology of tennis. Sports Med 14:

260268, 1992

9. Hageman CE, Lehman RC: Stretching, strengthening, and conditioning

for the competitive tennis player. Clin Sports Med 7: 211228, 1988

10. Ha kkinen K: Factors affecting trainability of muscular strength during

short-term and prolonged training. NSCA Journal 7: 3237, 1985

11. Ha kkinen K, Alen M, Komi PV: Changes in isometric force- and relaxation-

time, electromyographic and muscle fibre characteristics of human skel-

etal muscle during strength training and detraining. Acta Physiol Scand

125: 573585, 1985

12. Ha kkinen K, Pakarinen A, Alen M, et al: Relationships between training

volume, physical performance capacity, and serum hormone concentra-

tions during prolonged training in elite weight lifters. Int J Sports Med 8

(suppl): 6165, 1987

13. Ha kkinen K, Pakarinen A, Kyro la inen H, et al: Neuromuscular adaptations

and serum hormones in females during prolonged power training. Int

J Sports Med 11: 9198, 1990

14. Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A: Generalized equations for predicting

body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc 12: 175182, 1980

15. Jacobson BH: A comparison of two progressive weight training techniques

on knee extensor strength. Athletic Training 21: 315318, 1986

16. Kramer JB, Stone MH, OBryant HS, et al: Effects of single vs. multiple

sets of weight training: Impact of volume, intensity, and variation. J

Strength Cond Res 11: 143147, 1997

17. Kraemer WJ: A series of studies: The physiological basis for strength

training in American football: Fact over philosophy. J Strength Cond Res

11: 131142, 1997

18. Kraemer WJ, Fleck SJ, Dziados JE, et al: Changes in hormonal concen-

trations after different heavy-resistance exercise protocols in women.

J Appl Physiol 75: 594604, 1993

19. Kraemer WJ, Fry AC: Strength testing: Development and evaluation of

methodology, in Maud PJ, Foster C (eds): Physiological Assessment of

Human Fitness. Champaign, IL, Human Kinetics, 1995, pp 115138

20. Kraemer WJ, Gordon SE, Fleck SJ, et al: Endogenous anabolic hormonal

and growth factor responses to heavy resistance exercise in males and

females. Int J Sports Med 12: 228235, 1991

21. Kraemer WJ, Patton JF, Gordon SE, et al: Compatibility of high intensity

strength and endurance training on hormonal and skeletal muscle adap-

tations. J Appl Physiol 78: 976989, 1995

22. Kraemer WJ, Triplett NT, Fry AC, et al: An in-depth sports medicine profile

of women college tennis players. J Sport Rehabil 4: 7998, 1995

23. Liederman EE: Secrets of Strength. New York, E. Liederman, 1925

24. Messier SP, Dill ME: Alterations in strength and maximal oxygen uptake

consequent to Nautilus circuit weight training. Res Q Exerc Sport 56:

345351, 1985

25. Morrissey MC, Harman EA, Frykman PN, et al: Early phase differential

effects of slow and fast barbell squat training. Am J Sports Med 26:

221230, 1998

26. Mulligan SE, Fleck SJ, Gordon SE, et al: Influence of resistance exercise

volume on serum growth hormone and cortisol concentrations in women.

J Strength Cond Res 10: 256262, 1996

27. Newton RU, Kraemer WJ: Developing explosive muscular power: Impli-

cations for a mixed methods training strategy. J Strength Cond 16: 20,

1994

28. Ostrowski KJ, Wilson GJ, Weatherby R, et al: The effect of weight training

volume on hormonal output and muscular size and function. J Strength

Cond Res 11: 148154, 1997

29. Pollock ML, Graves JE, Bamman MM, et al: Frequency and volume of

resistance training: Effect on cervical extension strength. Arch Phys Med

Rehabil 74: 10801086, 1993

30. Powers SK, Walker R: Physiological and anatomical characteristics of

outstanding female junior tennis players. Res Q Exerc Sport 53: 172175,

1982

31. Reid CM, Yeater RA, Ullrich IH: Weight training and strength, cardiore-

spiratory functioning and body composition of men. Br J Sports Med 21:

4044, 1987

32. Sale DG: Neural adaptation to strength training, in Komi PV (ed): Strength

and Power in Sport. Boston, Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1991, pp

249265

632 Kraemer et al. American Journal of Sports Medicine

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

33. Sanborn K, Boros R, Hruby J, et al: Performance effects of weight training

with multiple sets not to failure versus a single set to failure in women. J

Strength Cond Res 14(2): 328331, 2000

34. Silvester LJ, Stiggins C, McGown C, et al: The effect of variable resistance

and free-weight training programs on strength and vertical jump. NSCA

Journal 3: 3033, 1982

35. Siri WE: Gross composition of the body, in Lawrence JH, Tobias CA (eds):

Advances in Biological and Medical Physics. Volume IV. New York, Aca-

demic Press, 1956

36. Starkey DB, Pollock ML, Ishida Y, et al: Effect of resistance training

volume on strength and muscle thickness. Med Sci Sports Exerc 28:

13111320, 1996

37. Staron RS, Leonardi MJ, Karapondo DL, et al: Strength and skeletal

muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining

and retraining. J Appl Physiol 70: 631640, 1991

38. Staron RS, Malicky ES, Leonardi MJ, et al: Muscle hypertrophy and fast

fiber type conversions in heavy resistance-trained women. Eur J Appl

Physiol 60: 7179, 1990

39. Stone MH, Johnson RL, Carter DR: A short term comparison of two

different methods of resistance training on leg strength and power. Athletic

Training 14: 158160, 1979

40. Stone MH, Plisk SS, Stone ME, et al: Athletic performance development:

Volume load - 1 set vs. multiple sets, training velocity and training varia-

tion. Strength Conditioning 20: 2231, 1998

41. Stowers T, McMillian J, Scala D, et al: The short-term effects of three

different strength-power training methods. NSCA Journal 5: 2427,

1983

42. Willoughby DS: Training volume equated: A comparison of periodized and

progressive resistance weight training programs. J Hum Mov Studies 21:

233248, 1991

Vol. 28, No. 5, 2000 Volume Effects on Resistance Training for Women Tennis Players 633

at Librero Editor S L on March 4, 2014 ajs.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Doom Horde Mode v1Dokument3 SeitenDoom Horde Mode v1Paco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1000stormcast PDFDokument1 Seite1000stormcast PDFPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AIS Recovery ReviewDokument18 SeitenAIS Recovery ReviewPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Protein Timing and Its Effects On Muscular Hypertrophy and Strength in Individuals Engaged in Weight-TrainingDokument8 SeitenProtein Timing and Its Effects On Muscular Hypertrophy and Strength in Individuals Engaged in Weight-TrainingthclaessNoch keine Bewertungen

- Changes in Athlete Burnout and Motivation Over A 12-Week League TournamentDokument10 SeitenChanges in Athlete Burnout and Motivation Over A 12-Week League TournamentPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Artículo Hoffman & Falvo. ProteinaDokument13 SeitenArtículo Hoffman & Falvo. ProteinaJm EspeletidasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kjormo y Halvari, 2002Dokument10 SeitenKjormo y Halvari, 2002Paco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bartholomew 2011Dokument15 SeitenBartholomew 2011Paco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Impacts of Talent Development Environments On Athlete Burnout: A Self-Determination PerspectiveDokument9 SeitenImpacts of Talent Development Environments On Athlete Burnout: A Self-Determination PerspectivePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2008 - Acute BoutsDokument5 Seiten2008 - Acute BoutsPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Dieta Protéica para Maximizar La ResitenciaDokument12 SeitenDieta Protéica para Maximizar La ResitenciaPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Efectos en Futbolistas de ColegioDokument8 SeitenEfectos en Futbolistas de ColegioPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kuitunen 02 Acute Reduction in Joint Stiffness After SSCDokument10 SeitenKuitunen 02 Acute Reduction in Joint Stiffness After SSCPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Whey Vs CaseinaDokument6 SeitenWhey Vs CaseinaPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kuitunen 02 Acute Reduction in Joint Stiffness After SSCDokument10 SeitenKuitunen 02 Acute Reduction in Joint Stiffness After SSCPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aagaard Isokinetic Hamstring Quadriceps 1998Dokument8 SeitenAagaard Isokinetic Hamstring Quadriceps 1998Paco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Measuring Power.5Dokument4 SeitenMeasuring Power.5Paco Parra Plaza100% (1)

- Behm 2011 A Review of The Acute Effects of Static and Dynamic Stretching On PerformanceDokument19 SeitenBehm 2011 A Review of The Acute Effects of Static and Dynamic Stretching On PerformancePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biomechanics of Power in SportDokument5 SeitenBiomechanics of Power in Sporthrvoje09100% (1)

- Ejemplo+de+aplicacioyn Changes+in+surface+EMG+assessed+by+discrete+wavelet+transform+during+maximal+isometric+voluntary+contractions+following+supramaximal+cyDokument10 SeitenEjemplo+de+aplicacioyn Changes+in+surface+EMG+assessed+by+discrete+wavelet+transform+during+maximal+isometric+voluntary+contractions+following+supramaximal+cyPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Abe Fasc Length 2000Dokument5 SeitenAbe Fasc Length 2000Paco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morin 05 A Simple Method For Measuring Stiffness During RunningDokument14 SeitenMorin 05 A Simple Method For Measuring Stiffness During RunningPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Exercise and Bone Mass in Adults: A Review of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal StudiesDokument30 SeitenExercise and Bone Mass in Adults: A Review of Cross-Sectional and Longitudinal StudiesPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Butler+2003+Lower+extremity+stiffness +implications+for+performanceDokument7 SeitenButler+2003+Lower+extremity+stiffness +implications+for+performancePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Leptin Receptors in Human Skeletal MuscleDokument8 SeitenLeptin Receptors in Human Skeletal MusclePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bloquesvsondulante DecathletasDokument10 SeitenBloquesvsondulante DecathletasPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HOBARA 2011 Determinant of Leg Stiffness During Hopping Is Frecuency DependentDokument7 SeitenHOBARA 2011 Determinant of Leg Stiffness During Hopping Is Frecuency DependentPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Myostatin Knockout Drives Browning of White Adipose Tissue Through Activating The AMPK-PGC1alpha-Fndc5 Pathway in MuscleDokument9 SeitenMyostatin Knockout Drives Browning of White Adipose Tissue Through Activating The AMPK-PGC1alpha-Fndc5 Pathway in MusclePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Critical Role For Free Radicals On Sprint Exercise-Induced CaMKII and AMPKalpha Phosphorylation in Human Skeletal MuscleDokument13 SeitenCritical Role For Free Radicals On Sprint Exercise-Induced CaMKII and AMPKalpha Phosphorylation in Human Skeletal MusclePaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- AMPK Regulation of Fatty Acid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Biogenesis Implications For ObesityDokument17 SeitenAMPK Regulation of Fatty Acid Metabolism and Mitochondrial Biogenesis Implications For ObesityPaco Parra PlazaNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Fitnes ProgramenDokument24 SeitenFitnes ProgramenpohanabrokulaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Year Round Strength and Conditioning PlanDokument72 SeitenYear Round Strength and Conditioning Planmalloryc100% (1)

- Components of Fitness Top Trumps MLloyd 2013Dokument7 SeitenComponents of Fitness Top Trumps MLloyd 2013vickimetcalfeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Article Body Weight SkillDokument9 SeitenArticle Body Weight Skillscotty_b57100% (1)

- Army Navy Seals Workout 2Dokument1 SeiteArmy Navy Seals Workout 2MAXI1000TUC100% (1)

- Dynamic Stretching For Your Workouts and TrainingDokument2 SeitenDynamic Stretching For Your Workouts and TrainingDominic Cadden100% (2)

- Class Timetable ʹ October 2010: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday SundayDokument1 SeiteClass Timetable ʹ October 2010: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday SundayalannahsparksNoch keine Bewertungen

- For More Turbulence Training Workouts, Visit:: © CB Athletic Consulting, 2007Dokument36 SeitenFor More Turbulence Training Workouts, Visit:: © CB Athletic Consulting, 2007mooney23Noch keine Bewertungen

- Daya Tahan KardiovaskularDokument33 SeitenDaya Tahan KardiovaskularLaoShiYuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Programa EjerciciosDokument5 SeitenPrograma EjerciciosKatherin P. AcostaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TheMuscleExperiment PDFDokument66 SeitenTheMuscleExperiment PDFShuvajoyyy100% (2)

- High Intensity Interval TrainingDokument2 SeitenHigh Intensity Interval TrainingmilleralselmoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Physical Preparation For Soccer (Soccer Specific - Com Version)Dokument205 SeitenPhysical Preparation For Soccer (Soccer Specific - Com Version)Doubles Standard100% (1)

- Nrol Blank Training Log For LifeDokument6 SeitenNrol Blank Training Log For Lifescason9100% (1)

- Last Callisthenics Book UploadedDokument89 SeitenLast Callisthenics Book Uploadedmiyamoto_musashi91% (23)

- Workout - Sheet - Wrestling Super Endurance 1 - 1477757519824 PDFDokument3 SeitenWorkout - Sheet - Wrestling Super Endurance 1 - 1477757519824 PDFEduard-Marian RoventaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vertical Jump PDFDokument6 SeitenVertical Jump PDFDominique DelannoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Advanced Bof ProgramDokument69 SeitenAdvanced Bof ProgramJJ Mid80% (5)

- Insanity Deluxe Workout Calendar Month 1 & 2Dokument1 SeiteInsanity Deluxe Workout Calendar Month 1 & 2Anonymous sTnEkqy4Noch keine Bewertungen

- Futsal FitnessDokument20 SeitenFutsal FitnessalmaformaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The 10 Best Plyometric Exercises For Athletes: 1. Front Box JumpDokument21 SeitenThe 10 Best Plyometric Exercises For Athletes: 1. Front Box Jumparmaan100% (1)

- Blackmir-Track Technique Session-Tempo Workouts For SprintersDokument4 SeitenBlackmir-Track Technique Session-Tempo Workouts For SprintersJosh Barge100% (1)

- Module in Physical FitnessDokument12 SeitenModule in Physical FitnessMillenieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cardiovascular Fitness Activity 1Dokument4 SeitenCardiovascular Fitness Activity 1Teguh SukmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- GRC PrelimDokument2 SeitenGRC PrelimFrancis PJ BegasoNoch keine Bewertungen

- San Antonio Spurs' Strength and Conditioning ProgramDokument4 SeitenSan Antonio Spurs' Strength and Conditioning Programeretria0% (1)

- BODY PUMP and The REP EFFECT - An Instructors Evaluation of The LDokument29 SeitenBODY PUMP and The REP EFFECT - An Instructors Evaluation of The LFITNoch keine Bewertungen

- Westside For Skinny BastardsDokument19 SeitenWestside For Skinny BastardsDave Gergescz100% (2)

- Self Care DeficitDokument3 SeitenSelf Care DeficitAddie Labitad100% (2)

- KettlebellDokument2 SeitenKettlebellVeeresh Sharma100% (2)