Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Environmental Economics, Water Allocation in South Africa and Grahamstown

Hochgeladen von

Andrew LawrieCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Environmental Economics, Water Allocation in South Africa and Grahamstown

Hochgeladen von

Andrew LawrieCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Andrew Lawrie

g12l0934

J.Polak

Period 4

Water Allocation

Economics 317

12 May 2014

Abstract

I understand that plagiarism is a serious offence and confirm that unless otherwise

acknowledged the content of this essay is my own.

Word count: 1657. (excluding quotations and in text referencing)

This paper seeks to explore: the challenges of efficiently allocating water,

pricing policies for water, the advantages and disadvantages of privatising

water in developing countries and ultimately whether or not privatization

of the water supply in Grahamstown could be use as a potential policy

remedy. This issue bears great importance because it could have a large

and positive impact on the allocation of water to citizens in Grahamstown

and South Africa alike. However, if considered erroneously the costs of

allocating water incorrectly could be devastating. The issue was addressed

by systematically considering each of the above issues, exploring the

current allocation system and finally considering whether or not

privatization of the water industry in Grahamstown would be beneficial. It

was concluded that such a venture would do more harm than good.

Table of contents:

- Introduction

- Current Water Allocation System

- Challenges Associated With Efficient Water Allocation

- Pricing Policies For Water Allocation

- For Privatization Of The Water Supply

- Against Privatization Of The Water Supply

- Privatization As A Policy Instrument in Grahamstown

- Conclusion

- List of References:

Introduction

The importance of access to water cannot be understated. Water is need by human beings in

order to compensate for their continual loss of body fluids thus allowing for their survival.

(Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 174). Human beings undeniable dependence on water for their

own survival qualifies it as one of the most essential, basic, economic needs. Grahamstown

has however, had a history of having inadequate service delivery when it comes to water and

its quality (Carte Blanche, 2013). Hence, with water in Grahamstown currently being

supplied by the Makana municipality as a public resource, the question arises of whether or

not the privatisation of Grhamstowns water supply would lead to more efficient supply while

allowing for other benefits that stem naturally from private business activity (Tietenberg and

Lewis, 2009:210).

This paper accordingly seeks to explore: the challenges of efficiently allocating water, pricing

policies for water, the advantages and disadvantages of privatising water in developing

countries and ultimately whether or not privatization of the water supply in Grahamstown

could be use as a potential policy remedy. A brief observation of South Africas current water

allocation system and how it developed is also supplied.

Current Water Allocation System

The current system of water allocation evolved from the implementation of two prior

systems. The first of these was the Riparian system which made use of riparion rights. These

rights gave control of the water to the owner of the land adjacent to the source of the water.

However, this system was shown to be wasteful and it lacked an efficient framework for the

transferability of the aforementioned rights (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 180). Hence, it was

these issues that lead to the establishment of the prior appropriation doctrine. Under this

doctrine, users received usufructory rights as opposed to ownership rights. Ownership was

held by the state. From this point onwards the state played an active role in transferring water

rights between different uses which resulted in the state controlling and allocating most of the

water resources today (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 181).

The water sector framework in South Africa has demonstrated a notable shift in its goals

relating to its management of water and its availability. Such a shift is becomes apparent

when considering the importance afforded to water in both the Bill of Rights and the National

Water Act (Bachurova, 2013). Following these pieces of legislation, the Department of Water

Affairs is mandated to further equal water distribution in South Africa (Department of Water

Affairs, 2013:29). However, such goals are progressive and have not been realized as yet.

Challenges Associated With Efficient Water Allocation

Challenges regarding efficient allocation of water hinge on whether the source of water in

question is surface water of groundwater. Surface water accumulates on the Earths surface.

When considering surface water, the challenges are as follows: the allocation of supply

among competing users, striking a balance between competing uses and determining a way to

manage and allocate variable flows of surface water (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 178).

The first challenge relates to the increasing demand and scarcity situation that exists

worldwide while the second denotes the issue of allocating water fairly between its various

consumptive or non consumptive uses. The final challenge with regard to surface water

occurs because of factors such as precipitation, run-off and evaporation changes lead to

different amount of surface water being available each year (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009:

179).

Groundwater constitutes water that collects in subterranean aquifers. Challenges regarding

groundwater include the fact that it can be contaminated and exhausted, its non-renewable

nature means that current use of groundwater will diminish future stock and issues will arise

if withdrawals outweigh recharges. The latter challenge means that these sources of water

will be used up if they are not recharged. However, they are often used until they are depleted

or until it costs too much to extract more water from them (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 179).

Two further challenges facing todays water allocation system would be poverty (Schreiner,

1999:5) and ironically, economic growth (Department of Water Affairs, 2013:29). Many of

South Africas poorest citizens cannot afford to pay the basic rates for water no matter how

small (Schreiner, 1999:2). However, simultaneously, the growth of South Africas economy,

which it so desperately needs, is also a challenge to water distribution. The necessary growth

in the economy places further demands on the already stressed supply of water in the country

(Department of Water Affairs, 2013:29).

Lastly, efficient water allocation in South Africa further suffers from a lack of water recycling

(Department of Water Affairs, 2013:29). Too much water ends up as unused wastewater as

opposed to it being treated and re-used for beneficial activities such as irrigation.

Pricing Policies For Water Allocation

Price levels and the rate structures with respect to water in South Africa are inefficient.

Seeing as water is a basic need, municipalities attempt to supply it at the lowest possible rates

(Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 183). The structures needed to distribute water are capital

intensive. Such utilities require large short run costs. Thus, in their attempt to provide water

cheaply, municipalities only charge people for the average variable costs of daily distribution

while the average fixed costs such as maintenance are not covered. This means that charging

a price at which marginal costs are equal to marginal revenues would yield a turnover that

falls below average total costs thus leading to an economic loss. Consequently, in the long

run, South African municipalities fall into debt which leads to further problems with water

provision (Tietenberg and Lewis, 2009: 184).

Various pricing policies exist with two-part charges, volumetric pricing, water market pricing

and tiered pricing being the most efficient, followed by input and output pricing being the

second most efficient and per-area pricing being completely inefficient (Tietenberg and

Lewis, 2009: 190). While these are still useful policies, water utilities should adopt a system

that features both increasing marginal cost and a scarcity value for groundwater (Tietenberg

and Lewis, 2009: 191). Such a pricing system would create a larger incentive for consumers

to limit to their water usage while ensuring a supply of water for future generations.

For Privatization Of The Water Supply

A more efficient pricing system could be achieved in the event of privatization of the water

industry. Privatization of the water supply would occur when publically owned water

distribution assets and rights are sold to a private company for their continued use.

Privatization offers many advantages to the supply of water. Incentive based operation is the

core of privatization (Tan, 2012:1) and in the presence of well-defined property rights, the

private owner bears the consequences of his actions. Such a condition also means that the

private owner would reap the profits of his efforts thus creating an incentive to supply water

more efficiently in order to meet demand. Such increased efficiency would counteract the

above mentioned inefficiency of the price levels of water and lead to more secure service

delivery (Tan, 2012:2552). Competition between private firms would also be introduced into

the water sector thus providing a further incentive to improve efficiency and quality (Miller,

2013:14). Private investment in the water industry would also incentivize the birth of new

innovations and technologies that would further aid the distribution and purification of water

(Miller, 2013:14). Furthermore, privatization has been shown to help mobilize financing,

implementation and investment programs, and improve performance of service delivery

(Miller, 2013:14). Lastly, limited public funds would not need to be further stretched to deal

with water distribution.

Against Privatization Of The Water Supply

However, privatization of course gives rise to certain drawbacks. Firms will charge a more

efficient price for water. This price will take all of their costs into account, plus a reasonable

rate of return, thus making it higher than when it was supplied publically (Miller, 2013:15). If

people were to withhold payment following this increased price, firms would have to cut their

water supply off. Such a practice would be unacceptable as the right to water is protected in

the South African constitution (Miller, 2013:15). Developing infrastructure for water

sanitation is also associated with high risks and uncertainty. At the same time, these projects

require massive funding, tax breaks and in many cases, subsidies from the local governments.

This makes poorer, which need water most, countries even less attractive to potential private

investors because their governments are unable to provide such financial incentives (Tan,

2012: 2555). Lastly, Water supply and sanitation has naturally monopolistic as the process of

isolating a water supply and setting up infrastructure to distribute and sanitize it does not

allow room for many firms to operate concurrently. A monopoly on water would lead to

higher prices and halt innovation thus devastating the many settlements and households that

can barely afford water as a public good (Tan, 2012:2554).

Privatization As A Policy Instrument in Grahamstown

Grahamstowns ongoing issues with water distribution can be attributed to various

phenomena such as aged and worn out infrastructure, unpredictable rainfall and drought

cycles and consistent operational issues regarding water supply (Ansie, 2013:1). As

previously stated, the Makana District municipality regulates water supply and distribution in

Grahamstown and their multiple shortcomings along with their apparent lack of expertise

(Carte Blanche, 2013:1) have brought questions of privatisation to light. In previous years,

Rhodes University, has demonstrated its stance on the matter of water shortages by releasing

a document on its website which considered the construction of its own reservoir at massive

costs after nearly closing down to allow students their right to hygiene and water. (Rumney,

2013:1). Furthermore, massive sums of money will be needed by the municipality in order to

upgrade their outdated system (Haith, 2014:1). On top of the above reasoning, the levels of

arsenic and aluminium present in Grahamstowns water (Ansie, 2013:1) build a strong case

for privatization of water in Grahamstown.

However, the drawback of higher water prices which appears to be unavoidable would leave

too many Grahamstown occupants without water. While the wealthy would be able to pay,

the poor majority of the city would be devastated and their problem of lacking access to water

would be replaced by the problem of not being able to afford water (Nodada, 2013:1). This

issue cannot be circumvented. Regulation of the private water scheme could assist the poor.

However, especially in country such as South Africa, corruption and political agendas appear

to make their way into important regulatory schemes (Tan, 2010:2555). Something

Grahamstowns people, schools and university can ill afford.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it can be seen that the many challenges associated with water distribution and

supply need to be carefully considered when deciding how water should be allocated. Once a

method of allocation has been decided upon, bearing in mind the challenges of such an

endeavour, a suitable pricing policy needs to be established. While there are many pre-

existing policies that can be applied, a policy that more fully captures the costs of water

allocation should be adopted to achieve maximum efficiency. While privatisation of the water

industry may offer such efficiency and further security of service delivery, it also has

potential drawbacks that may result in more harm than good to a society. In the context of

Grahamstown, privatization could provide the city with much needed improvements in

service delivery. However, it can be seen that the inevitable increases in the price of water

along with water services monopolistic nature would indeed do more harm than good to

Grahamstowns citizens. The solution therefore lies within improving government allocation

mechanisms to better suit Grahamstown.

List of References:

ANSIE, 2013. Is Grahamstown water safe yet? [Online]. Available:

http://www.watersafe.co.za/2010/03/31/is-grahamstowns-water-safe-yet/

[Accessed 12 May 2014].

BACHUROVA, A, 2013. Water Allocation. [Online]. Available:

http://www.iwawaterwiki.org/xwiki/bin/view/Articles/WaterAllocation

[Accessed 12 May 2014].

CARTE BLANCHE, 2013. Grahamstown Water. Carte Blanche. 23 September 19:00.

Carte Blanche [Online] Available: http://carteblanche.dstv.com/story/Grahamstown-Water-

2013-09-29 [Accessed 12 May 2014].

DEPARTMENT OF WATER AFFAIRS, 2013. Overview of The South African Water Sector.

[Online]. Available:

http://www.dwa.gov.za/io/Docs/CMA/CMA%20GB%20Training%20Manuals/gbtrainingman

ualchapter1.pdf [Accessed 12 May 2014].

HAITH, C, 2014. Grahamstown Not Clear of Water Worries Yet. [Online]. Available:

http://oppidanpress.com/grahamstown-not-clear-of-water-worries-yet [Accessed 12 May

2014].

MILLER, M, 2013. The impact of privatisation on the sustainability of water resources.

[Online]. Available:

http://www.iwawaterwiki.org/xwiki/bin/view/Articles/THEIMPACTOFPRIVATISATIONON

THESUSTAINABILITYOFWATERRESOURCES#HPositiveExperiencesfromselectedcountr

ies [Accessed 12 May 2014].

NODADA, L, 2013. Water debate raises moral hackles. [Online]. Available:

http://www.grocotts.co.za/content/water-debate-raises-moral-hackles-07-03-2013 [Accessed

12 May 2014].

RUMNEY, R, 2013. Water Crisis: Social Cohesion At Stake. [Online]. Available:

http://www.grocotts.co.za/content/social-cohesion-stake-24-03-2013 [Accessed 12 May

2014].

SCHREINER, B, 1999. The Challenges Of Water Resource Management In South Africa.

[Speech].

TAN, J. The Pitfalls of Water Privatization: Failure and Reform in Malaysia World

Development 40, 12: 2552-2563

TIETENBERG, T. and LEWIS, L., 2009. Environmental Economics and Policy (6

th

edition).

Essex, England: Pearson Education Ltd.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Agency Cases on Sub-Agents and Fiduciary DutiesDokument10 SeitenAgency Cases on Sub-Agents and Fiduciary DutiesAndrew Lawrie75% (4)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

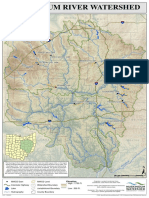

- Muskingum Watershed Conservancy DistrictDokument1 SeiteMuskingum Watershed Conservancy DistrictRick ArmonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Heat Exchanger Design for CCHP SystemDokument24 SeitenHeat Exchanger Design for CCHP Systemmkfe2005Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ Proc B Case Notes TitleDokument166 SeitenCiv Proc B Case Notes TitleAndrew Lawrie0% (2)

- T F T T T: Name: - DateDokument5 SeitenT F T T T: Name: - DateSamantha NortonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reservoir System GuideDokument296 SeitenReservoir System Guideryan emanuelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Water Supply NotesDokument13 SeitenWater Supply NotesVenkat RamanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Admin Law Case NotesDokument73 SeitenAdmin Law Case NotesAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gas AbsorptionDokument43 SeitenGas AbsorptionJoel Ong0% (1)

- Line Sizing Philosophy PDFDokument21 SeitenLine Sizing Philosophy PDFmohammadhadiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reverse OsmosisDokument53 SeitenReverse Osmosisanabloom100% (2)

- Partnerships AssignmentDokument7 SeitenPartnerships AssignmentAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence AssignmentDokument7 SeitenJurisprudence AssignmentAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurisprudence AssignmentDokument7 SeitenJurisprudence AssignmentAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Partnerships AssignmentDokument7 SeitenPartnerships AssignmentAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Law of Contract AssignmentDokument9 SeitenLaw of Contract AssignmentAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Std11 Acct EMDokument159 SeitenStd11 Acct EMniaz1788100% (1)

- Crw2601u Study Guide NotesDokument60 SeitenCrw2601u Study Guide NotesAndrew LawrieNoch keine Bewertungen

- Flow of Incompressible Fluids in Conduits & Thin LayersDokument22 SeitenFlow of Incompressible Fluids in Conduits & Thin LayerssaimaabdulrasheedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Compression and Expansion of GasesDokument5 SeitenCompression and Expansion of GasesmishraenggNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fluid MechDokument10 SeitenFluid MechPetForest Ni JohannNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laboratory Report DistillationDokument3 SeitenLaboratory Report DistillationQueenie Luib MapoyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Test Ch#3 1st YearDokument3 SeitenTest Ch#3 1st YearRashid Jalal100% (1)

- TCWY PROFILE General PDFDokument36 SeitenTCWY PROFILE General PDFhendntdNoch keine Bewertungen

- CalcI&II Compre.2ndsem1718Dokument1 SeiteCalcI&II Compre.2ndsem1718Dianne Aicie ArellanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bab 2 Pure SubstancesDokument24 SeitenBab 2 Pure SubstancesDaneal FikriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Given: F 100 Mol (N-Pentane) 0.60 (N - Heptane) 0.40 101.32 40 60Dokument6 SeitenGiven: F 100 Mol (N-Pentane) 0.60 (N - Heptane) 0.40 101.32 40 60Yasmin KayeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solved Problems Ref SystemDokument5 SeitenSolved Problems Ref SystemArchie Gil DelamidaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mazhapolima Presentation DR V Kurien BabyDokument23 SeitenMazhapolima Presentation DR V Kurien BabyVeettal KurianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Natural Gas Dehydration MethodsDokument5 SeitenNatural Gas Dehydration MethodsShaniz KarimNoch keine Bewertungen

- HW2Dokument3 SeitenHW2ghngNoch keine Bewertungen

- Experiment No. 2 Molar Mass of A Volatile LiquidDokument5 SeitenExperiment No. 2 Molar Mass of A Volatile LiquidJericho MaganaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Libroflng2014 PDFDokument2 SeitenLibroflng2014 PDFmchavez_579229Noch keine Bewertungen

- Final Year Project Mid Defense Argon Recovery ProcessDokument6 SeitenFinal Year Project Mid Defense Argon Recovery ProcessKhizAr Hayat KhizArNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamental of Exploration and ProductionDokument34 SeitenFundamental of Exploration and ProductionVelya Galyani Pasila Galla100% (1)

- Hydrology For DummiesDokument20 SeitenHydrology For DummiesIulian Mihai50% (2)

- Waterworks Technologies of Fukuoka CityDokument16 SeitenWaterworks Technologies of Fukuoka CityFelipe Andres Guajardo ArriagadaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cengel FTFS 6e ISM CH 10Dokument44 SeitenCengel FTFS 6e ISM CH 10Duck FernandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Steam Turbines Questions and AnswersDokument4 SeitenSteam Turbines Questions and AnswersMshelia M.0% (1)

- Water Resources-NotesDokument14 SeitenWater Resources-NotesHarshwardhan UndeNoch keine Bewertungen