Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Eur J Orthod 2002 Hunt 53 9

Hochgeladen von

Jade M. Lolong0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

20 Ansichten8 Seitenorthodontic index

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenorthodontic index

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

20 Ansichten8 SeitenEur J Orthod 2002 Hunt 53 9

Hochgeladen von

Jade M. Lolongorthodontic index

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

Introduction

It was recognized over three decades ago that

any meaningful evaluation of the need for ortho-

dontic treatment must include an assessment of

the aesthetic impairment of a malocclusion

(Federation Dentaire Internationale, 1970).

Others have also concluded that reliable

measures of dental aesthetics are essential if

the social and psychological implications of

malocclusion are to be assessed (Howells and

Shaw, 1985). Further indirect support for the use

of measures of aesthetic impairment have come

from longitudinal studies of the relationship

between malocclusion and dental disease (Addy

et al., 1988; Helm and Peterson, 1989; Shaw et al.,

1991). These investigations confirmed that, in the

main, the ill-effects of malocclusion were

psychosocial in nature and related to the

aesthetic impairment, rather than any functional

disadvantage. It is therefore not surprising that

when the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need

(IOTN; Brook and Shaw, 1989) was developed it

contained a standardized measure of dental

aesthetic impairment, the Aesthetic Component

(AC), which is applied entirely independently of

the rating of functional disability or occlusal

discrepancy (Dental Health Component). The

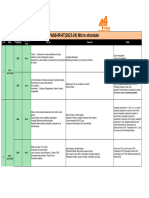

AC consists of a series of 10 colour photographs

arranged on a continuum of attractiveness, with

grade 1 being the most attractive and grade 10

the least attractive (Figure 1).

During the initial development of IOTN,

the subjective opinion of 74 dentists (44 ortho-

dontists and 30 non-orthodontists) was used to

validate the cut-off points representing the

different levels of orthodontic treatment need.

The results of that validation exercise found that

according to professional opinion grades 14

of the AC represent no need for orthodontic

treatment, grades 57 represent borderline need,

and grades 810, definite need for treatment

European Journal of Orthodontics 24 (2002) 5359 2002 European Orthodontic Society

The Aesthetic Component of the Index of Orthodontic

Treatment Need validated against lay opinion

Orlagh Hunt*, Peter Hepper**, Chris Johnston*, Mike Stevenson*** and

Donald Burden*

*Division of Orthodontics, **School of Psychology and ***Department of Epidemiology and

Public Health, Queens University Belfast, UK

SUMMARY This study aimed to determine the threshold of aesthetic impairment where

orthodontic treatment would be sought by a sample of lay people. Using the 10-grade

Aesthetic Component (AC) scale of the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need (IOTN),

215 university students selected the level of aesthetic impairment that represented the

point at which they would seek orthodontic treatment.

Only nine (4.3 per cent) of the respondents recorded a threshold grade beyond grade 5

in the AC. The AC photograph grade 4 was found to be the most commonly selected

threshold photograph. Subjects who visited the dentist every 6 months were more likely to

choose a threshold photograph closer to the attractive end of the scale than those who

visited their dentist less frequently (P < 0.01).

This study, using lay people rather than dental health professionals, suggests that as

currently used the AC does not reflect societys aesthetic expectations. The results indicate

that when using the AC of the IOTN the no need for treatment category should be grades

13 of the AC, rather than grades 14.

(Richmond et al., 1995). This approach of using

the subjective opinion of clinicians to verify

treatment need thresholds is not unique and was

used by earlier workers to validate other occlusal

indices (Salzmann, 1968; Summers, 1971; Jenny

et al., 1983). Since its introduction by Brook

and Shaw (1989) the IOTN has been widely

embraced by orthodontists throughout the world

(Shaw et al., 1995). However, from a scientific

perspective, it could be argued that the use of

professional opinion to validate an orthodontic

aesthetic ranking scale is inherently flawed.

Numerous studies have confirmed that, by

virtue of their training and experience, dental

professionals are conditioned to take an overly

critical view of any deviation from normal

occlusion (Shaw et al., 1975; Prahl-Andersen,

1978). Many dentists favour an interventional

54 O. HUNT ET AL.

Figure 1 The Aesthetic Component (AC) of the IOTN (Brook and Shaw, 1989).

approach even where this is not sought by the

patient or parent, and may not necessarily be of

significant benefit (Shaw et al., 1975; Prahl-

Andersen, 1978; Downer, 1987).

There is, therefore, evidence to support the

view that the AC of the IOTN should be valid-

ated against the opinion of people who are not

dental professionals. The only previous study

that has attempted to do this (Stenvik et al.,

1997) was compromised by virtue of the fact that

the subjects included children who had already

been selected for orthodontic treatment.

The present study aimed to determine the

threshold at which a sample of lay people would

seek orthodontic intervention and to compare

this with the threshold level currently suggested

by the AC of the IOTN.

Methods

Two hundred and fifteen social science students

who were in their first or second year at

university were asked to complete a question-

naire to determine the point at which they would

wish to receive orthodontic treatment. The

subjects comprised 53 males (24.7 per cent) and

162 females (75.3 per cent) with a median age

19 years (range of 1743 years). The questionnaires

were completed during two separate lectures,

one consisting of 75 students, the other consisting

of 140 students.

A 35-mm colour slide of the AC of the IOTN

was projected onto a 15 10-m screen in a lecture

theatre containing approximately 100 students

at any one time. The purpose and use of the

AC were explained in a few paragraphs at the

beginning of the questionnaire. Participants

were instructed to record the AC grade that

indicated the point at which they would seek

treatment if the photographs represented their

own dentition. In addition, the students also

rated the attractiveness of their own teeth (very

unattractive, unattractive, attractive, or very

attractive) and the importance that they attrib-

uted to having straight teeth (very unimportant,

unimportant, important, or very important).

Each student was asked about their personal

experience of orthodontic treatment in terms of

whether they had ever been referred for

orthodontic treatment, if they felt they should

have been referred, whether they had ever

received orthodontic treatment, or if they had

ever refused orthodontic treatment. In addition,

the subjects were asked how frequently they

attended the dentist (every 6 months, once a

year, every 2 years, less often than every 2 years,

only when in pain, never), and if anyone in their

immediate family had ever received orthodontic

treatment. Subjects were asked not to confer

when completing the questionnaires.

Data analysis was performed using the

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS,

Version 9, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois).

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the

subjects histories in relation to their orthodontic

experiences and their dental attendance rates.

The relationship between the choice of threshold

photograph and the participant variables was

analysed using forward stepwise linear regres-

sion with the AC rating as the dependent

variable. Independent variables entered into the

analysis included age, gender, whether or not

participants had been referred for orthodontic

treatment, if they felt they should have been

referred, if they had ever received orthodontic

treatment, and if they had ever refused

orthodontic treatment. The frequency of dental

attendance and whether anyone in their

immediate family had ever received orthodontic

treatment were also entered into the analysis.

Linear regression analysis was also used to

examine the relationship between each subjects

opinion of the attractiveness of their own teeth,

the importance of having straight teeth, and their

choice of threshold photograph in the AC. A

2

test was used for tests of association involving

categorical data.

Results

Previous experience of orthodontic treatment

The questionnaires returned by four subjects

were incomplete for this section and were

therefore not included. Ninety-two (43.6 per

cent) of the remaining sample reported that they

had received orthodontic treatment and 119

(56.4 per cent) reported that they had not.

AESTHETIC COMPONENT OF IOTN 55

Among those who did not receive orthodontic

treatment, 28 (23.5 per cent) had been offered

treatment, but declined and a further 30 subjects

(25.2 per cent) felt they should have been

referred for treatment. One hundred and twenty

subjects (56.8 per cent) reported that a family

member had received orthodontic treatment.

Frequency of dental attendance

One hundred and twenty subjects (55.8 per cent)

reported that they attended the dentist every

6 months, while a further 49 (22.8 per cent)

subjects reported that they visited their dentist

once a year. Therefore, the majority of

participants (78.6 per cent) attended the dentist

at least once a year.

Threshold where orthodontic treatment would

be sought

The AC grade 4 was found to be the most

commonly selected threshold photograph

(Table 1). Ninety-two (42.8 per cent) of the

sample selected this grade as the point in the

scale of severity at which they would seek

orthodontic treatment if the photographs had

represented their own dentition. Figure 2 shows

the threshold grade selected by the whole

sample. By grade 4, 74 per cent of the sample

reported that they would seek orthodontic

treatment and by grade 5, 95.8 per cent of the

sample would seek orthodontic treatment. Only

nine (4.3 per cent) of the respondents recorded a

threshold grade beyond grade 5 of the AC

(Figure 2).

Linear regression analysis was used to explore

the relationship between the threshold level

selected and each subjects orthodontic experi-

ence and dental attendance. The only variable

that was found to influence the cut-off point

chosen on the AC scale was the frequency of

dental attendance. Those who visited their

dentist more regularly chose a cut-off grade

closer to the more attractive end of the scale

compared with those who attended their dentist

less frequently (P < 0.05).

The relationship between frequency of dental

attendance and the selected threshold grade of

the AC is illustrated in Table 2. Analysis using

the

2

test revealed a significant association

between those participants who visit the dentist

every 6 months and selection of grade 3 or less

on the AC (

2

= 9.88, P < 0.01, df = 1).

Subjects rating of the attractiveness of own teeth

and their opinion on the importance of having

straight teeth

The responses to this section of the question-

naire are reported in Table 3. The majority of the

subjects (67.9 per cent) considered that their own

dentitions were attractive or very attractive.

In addition, the majority of respondents

56 O. HUNT ET AL.

Table 1 The Aesthetic Component (AC) grade

where orthodontic treatment would be requested

(n = 215).

AC grade No. of Percentage Cumulative

subjects of subjects percentage

1 2 0.9 0.9

2 28 13.0 14.0

3 37 17.2 31.2

4 92 42.8 74.0

5 47 21.9 95.8

6 1 0.5 96.3

7 2 0.9 97.2

8 1 0.5 97.7

9 1 0.5 98.1

10 4 1.9 100.0

Figure 2 The Aesthetic Component (AC) grade where

orthodontic treatment would be requested.

(86.5 per cent) also felt it was important or

very important to have straight teeth (Table 3).

Linear regression analysis was conducted to

determine whether the participants opinion of

the attractiveness of their own dentition and

their perceptions of the importance of having

straight teeth influenced their choice of cut-off

point for treatment using the AC of the IOTN.

No significant relationship was found between

participants ratings of the attractiveness of their

own teeth and their choice of threshold

photograph on the AC (P = 0.88). Although not

quite achieving statistical significance, the

analysis revealed a trend for those participants

who considered having straight teeth as

important to choose an AC photograph closer to

the attractive end of the scale (P = 0.07).

Discussion

This study used the consensus opinion of a large

sample of university students to determine the

acceptable limit of dental aesthetic impairment.

The sample chosen represented a wide range of

lay opinion, including those who had had

orthodontic treatment and those who had not.

Although no evidence exists to suggest that the

aesthetic preferences of university students

differ from other young adults, this possibility

must be considered when interpreting the results

of this study.

Previous investigations have found that

females tend to express greater concern about

their facial appearance than males (Tung and

Kiyak, 1998). Whilst the current sample included

more females than males, linear regression

analysis did not detect any gender influence

on the threshold chosen for the initiation of

orthodontic treatment.

At the time when this cohort were adolescents,

orthodontic treatment was widely available and

even if they did not receive orthodontic care

themselves, many of their peers did so. A recent

survey in Northern Ireland revealed that, among

15- and 16-year-olds, 28 per cent had received

orthodontic treatment (Breistein and Burden,

1998). In the current study, 43 per cent of the

subjects reported that they had received

orthodontic treatment. Even allowing for those

who had orthodontic treatment after 16 years of

age the sample contained a higher than average

level of subjects who had received orthodontic

treatment. However, this meant that the sample

was almost equally divided between individuals

with and without personal experience of

orthodontic treatment. The results of this study

therefore provide a contemporary view of

societys perception of acceptable dental

aesthetics among individuals with an up-to-date

awareness of the potential benefits of ortho-

dontic treatment. A majority of the subjects

(87 per cent) reported that having straight teeth

AESTHETIC COMPONENT OF IOTN 57

Table 2 The relationship between the frequency

of dental attendance and choice of Aesthetic

Component (AC) grade.

AC grade Attends every Attends less often than

6 months every 6 months

n (cumulative n (cumulative

percentage) percentage)

1 1 (0.8) 1 (1.1)

2 22 (19.2) 6 (7.4)

3 25 (40.0) 12 (20.0)

4 41 (74.2) 51 (73.7)

5 26 (95.8) 21 (95.8)

6+ 5 (100) 4 (100)

Table 3 Subjects perception of the attractiveness

of their own teeth and the importance of having

straight teeth (n = 215).

No. of Percentage

participants of sample

How attractive do you think your teeth are?

Very unattractive 5 2.3

Unattractive 61 28.4

Attractive 134 62.3

Very attractive 12 5.6

Missing data 3 1.4

How important is it to have straight teeth?

Very unimportant 6 2.8

Unimportant 20 9.3

Important 141 65.6

Very important 45 20.9

Missing data 3 1.4

was important or very important. The age group

of the sample (mean = 20.3 years) was also

considered to be sufficiently mature to be able to

make a balanced judgement on the relative

influence of dental aesthetics on social accept-

ability, self-esteem, and self-confidence. An

earlier similar study found that children were

significantly less critical in their aesthetic

judgements than young adults (Stenvik et al.,

1997).

It could be argued that dental professionals

are best placed to make judgements on the

aesthetic values held by potential patients and

their families. However, there is evidence that

dental professionals assessment of aesthetic

acceptability differs from the layperson (Prahl-

Andersen, 1978; Shaw et al., 1980). This means

that the thresholds adopted in the AC of the

IOTN for determining who is and who is not

in need of orthodontic treatment may represent

the biased view of a small group of dental

professionals, rather than the wider view of

society.

In this investigation the subjects were asked

to decide at what point they would seek

orthodontic treatment using the continuum of

dental aesthetic impairment represented by the

AC. The results indicate that the level of

aesthetic impairment represented by grades 6

through to 10 were considered to require ortho-

dontic treatment by 100 per cent of the subjects

surveyed. The young adults therefore agree with

the professionals assessment that individuals

with this level of aesthetic impairment are in

need of orthodontic treatment.

In this type of study, it is always difficult to

define the point on a scale of dental

attractiveness where orthodontic intervention

should be contemplated. However, the results

indicate that by the time grade 4 was reached a

majority of the participants (74 per cent) had

indicated that they would seek orthodontic

treatment. A large proportion of the subjects

(42 per cent) felt that orthodontic treatment

was needed to correct the level of aesthetic

impairment represented by grade 4 on the IOTN

AC. This result conflicts with the professionally

defined threshold currently used by the AC of

IOTN (Richmond et al., 1995). In normal use, all

the grades up to and including grade 4 of the AC

are considered to represent little or no need for

orthodontic treatment (Richmond et al., 1995),

yet the majority of this sample of young adults

reported that they would seek orthodontic care

at a lower level of aesthetic impairment. There is

strong evidence from this study to suggest that

the threshold point for the initiation of

orthodontic treatment should be lowered to

grade 3 of the AC, and the little or no need

category should only include grades 13.

Only one previous investigation has compared

the professionally defined cut-off values of the

AC with the opinion of lay people. In that

Norwegian study, 137 children, 126 of their

parents, and 98 young adults were asked to

record if any of the 10 dentitions in the AC

required orthodontic correction (Stenvik et al.,

1997). The authors found that in the three groups

studied the threshold selected for orthodontic

intervention was grade 5 of the AC. They

therefore concluded that Norwegian lay people

were in agreement with the professionally

defined no need for treatment grouping (grades

14 of the AC). It is difficult to explain the

different findings between this previous study

and the present investigation. However, in the

Norwegian study the way in which the AC was

used was apparently not explained to the

subjects and they were not asked specifically to

select a threshold image on the continuum.

Nearly one-third (31 per cent) of those

questioned in the current study felt that they

would seek orthodontic treatment for the level

of aesthetic impairment represented by grades

23 of the AC. This confirms the high

expectations of dental aesthetic perfection

among lay people. However, it seems reasonable

to define the threshold for the initiation of

orthodontic treatment at the point where the

majority of lay people would seek treatment,

i.e. grade 4. Orthodontic treatment need indices,

such as the IOTN, provide the opportunity to

reduce subjective bias in determining who is in

need of orthodontic treatment and who is not.

However, to be scientifically valid occlusal

indices must correctly identify those in need.

This investigation using lay people rather than

dentists suggests that, as currently used, the AC

58 O. HUNT ET AL.

does not reflect societys aesthetic expectations.

To truly reflect lay opinion, a minor adjustment

is required to the AC to lower the threshold

point for the initiation of treatment by one grade

from grade 4 to grade 3.

Using multivariate analysis, the only factor

found to influence the choice of threshold for

the initiation of orthodontic treatment was the

frequency with which the subjects visited their

dentist. Those who attended their dentist more

frequently (every 6 months) tended to have a

lower threshold for the initiation of orthodontic

treatment than those who attended less

frequently. This most likely reflects the greater

emphasis placed on dental health and dental

appearance by regular dental attenders.

Conclusions

1. Aesthetic ranking scales used in orthodontic

treatment need indices should be validated

using lay people who have a good awareness

of orthodontic treatment.

2. The results of this study indicate that the

threshold for the initiation of orthodontic

treatment defined by the AC of the IOTN

should be lowered so that grade 4 is included

in the treatment need category.

3. This study also found that regular dental

attenders had higher expectations of dental

aesthetics than those who visited their dentist

less frequently.

Address for correspondence

Ms Orlagh Hunt

Division of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry

Queens University of Belfast

Royal Victoria Hospital

Grosvenor Road

Belfast BT12 6BP

UK

References

Addy M et al. 1988 The association between tooth

irregularity and plaque accumulation, gingivitis and

caries in 1112 year-old-children. European Journal of

Orthodontics 10: 7683

Breistein B, Burden D J 1998 Equity and orthodontic

treatment: a study among adolescents in Northern

Ireland. American Journal of Orthodontics and

Dentofacial Orthopedics 113: 408413

Brook P H, Shaw W C 1989 The development of an index

of orthodontic treatment priority. European Journal of

Orthodontics 11: 309320

Downer M 1987 Craniofacial anomaliesare they a public

health problem? International Dental Journal 37:

193196

Federation Dentaire Internationale 1970 Epidemiological

assessment of dentofacial anomalies. Transactions of the

second FDI conference on oral epidemiology. Inter-

national Dental Journal 20: 563656

Helm S, Peterson P E 1989 Causal relation between

malocclusion and caries. Acta Odontologica

Scandinavica 47: 217221

Howells D J, Shaw W C 1985 The validity and reliability of

ratings of dental and facial attractiveness for epidemi-

ologic use. American Journal of Orthodontics 88: 402408

Jenny J, Cons N C, Kohout F J 1983 Comparison of SASOC,

a measure of dental aesthetics, with three orthodontic

indexes and orthodontist judgement. Community

Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 11: 236241

Prahl-Andersen B 1978 The need for orthodontic

treatment. Angle Orthodontist 48: 19

Richmond S, Shaw W C, OBrien K D, Buchanan I B,

Stephens C D, Andrews M, Roberts C T 1995 The

relationship between the index of orthodontic treatment

need and consensus opinion of a panel of 74 dentists.

British Dental Journal 178: 370374

Salzmann J A 1968 Handicapping malocclusion assessment

to establish treatment priority. American Journal of

Orthodontics 54: 749765

Shaw W C, Lewis H G, Robertson N R 1975 Perception of

malocclusion. British Dental Journal 138: 2116

Shaw W C, Addy M, Ray C 1980 Dental and social effects

of malocclusion and effectiveness of orthodontic

treatment: a review. Community Dentistry and Oral

Epidemiology 8: 3645

Shaw W C, OBrien K D, Richmond S, Brook P 1991

Quality control in orthodontics: risk/benefit consider-

ations. British Dental Journal 170: 3337

Shaw W C, Richmond S, OBrien K D 1995 The use of

occlusal indices: a European perspective. American

Journal of Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics

107: 110

Stenvik A, Espeland L, Linge B O, Linge L 1997 Lay

attitudes to dental appearance and need for orthodontic

treatment. European Journal of Orthodontics 19:

271277

Summers C J 1971 The Occlusal Index: a system for

identifying and scoring occlusal disorders. American

Journal of Orthodontics 59: 552567

Tung A W, Kiyak H A 1998 Psychological influences on the

timing of orthodontic treatment. American Journal of

Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics 113: 2939

AESTHETIC COMPONENT OF IOTN 59

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Dental Referral FormDokument1 SeiteDental Referral FormJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- K20 Engine Control Module X3 (Lt4) Document ID# 4739106Dokument3 SeitenK20 Engine Control Module X3 (Lt4) Document ID# 4739106Data TécnicaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nomad Pro Operator ManualDokument36 SeitenNomad Pro Operator Manualdavid_stephens_29Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rotary Valve Functions BookletDokument17 SeitenRotary Valve Functions Bookletamahmoud3Noch keine Bewertungen

- JournalDokument5 SeitenJournalJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Managing Carious LesionsDokument1 SeiteManaging Carious LesionsJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Association of Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Snacking Habits With The Risk of Early Childhood Caries Among 3-Year-Old Japanese ChildrenDokument6 SeitenAssociation of Environmental Tobacco Smoke and Snacking Habits With The Risk of Early Childhood Caries Among 3-Year-Old Japanese ChildrenJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Observed Child and Parent Tooth Brushing Behaviors and Child Oral HealthDokument9 SeitenObserved Child and Parent Tooth Brushing Behaviors and Child Oral HealthJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ghazal Factors Associated With Early Childhood Caries Incidence Among High Caries-Risk ChildrenDokument9 SeitenGhazal Factors Associated With Early Childhood Caries Incidence Among High Caries-Risk ChildrenJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- S2 2013 323973 BibliographyDokument6 SeitenS2 2013 323973 BibliographyJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Evaluation of Fractured Condylar Head Along The Sagittal Plane Report of Three CasesDokument4 SeitenEvaluation of Fractured Condylar Head Along The Sagittal Plane Report of Three CasesJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- To Pack or Not To Pack: The Current Status of Periodontal DressingsDokument14 SeitenTo Pack or Not To Pack: The Current Status of Periodontal DressingsJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Evaluation of Root Canal Obturation Methods in Primary TeethDokument9 SeitenClinical Evaluation of Root Canal Obturation Methods in Primary TeethJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Policy On Oral HabitsDokument2 SeitenPolicy On Oral HabitsJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preparation of Adhesive Inlays and Onlays.Dokument5 SeitenPreparation of Adhesive Inlays and Onlays.Jade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Candida-Associated Denture StomatitisDokument5 SeitenCandida-Associated Denture StomatitisJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- G PulpDokument9 SeitenG PulpwindhaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subcutaneous Emphysema During Third Molar Surgery: A Case ReportDokument4 SeitenSubcutaneous Emphysema During Third Molar Surgery: A Case ReportEdric MichaelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Preliminary Impressions in Microstomia Patients An InnovativeDokument4 SeitenPreliminary Impressions in Microstomia Patients An InnovativeJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Osteomyelitis of The Mandible in A Patient With Osteopetrosis Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDokument6 SeitenOsteomyelitis of The Mandible in A Patient With Osteopetrosis Case Report and Review of The LiteratureJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Palatal Perforation Secondary To Tuberculosis A Case ReportDokument3 SeitenPalatal Perforation Secondary To Tuberculosis A Case ReportJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparacao Entre TecnicasDokument14 SeitenComparacao Entre TecnicasjoserodrrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spring-Bite: A New Device For Jaw Motion Rehabilitation. A Case ReportDokument4 SeitenSpring-Bite: A New Device For Jaw Motion Rehabilitation. A Case ReportJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Location and Presence of Permanent Teeth in A Complete Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate PopulationDokument6 SeitenLocation and Presence of Permanent Teeth in A Complete Bilateral Cleft Lip and Palate PopulationJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rehabilitation of Atrophic Maxilla A Review of 101 Zygomatic ImplantsDokument8 SeitenRehabilitation of Atrophic Maxilla A Review of 101 Zygomatic ImplantsJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceph HandoutDokument18 SeitenCeph Handoutwaheguru13he13Noch keine Bewertungen

- Occlusal Plane Location in Edentulous Patients A ReviewDokument7 SeitenOcclusal Plane Location in Edentulous Patients A ReviewJade M. Lolong50% (2)

- Occlusal Plane Location in Edentulous Patients A ReviewDokument7 SeitenOcclusal Plane Location in Edentulous Patients A ReviewJade M. Lolong50% (2)

- Case Report of Difficult Dental Prosthesis Insertion Due To Severe Gag ReflexDokument7 SeitenCase Report of Difficult Dental Prosthesis Insertion Due To Severe Gag ReflexJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ceph TracingDokument1 SeiteCeph TracingJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Luxation InjuriesDokument4 SeitenLuxation InjuriesJade M. LolongNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tabel IotnDokument3 SeitenTabel IotnPuspita PutriNoch keine Bewertungen

- Microcontroller Based Vehicle Security SystemDokument67 SeitenMicrocontroller Based Vehicle Security Systemlokesh_045Noch keine Bewertungen

- PDC NitDokument6 SeitenPDC NitrpshvjuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coek - Info The Fabric of RealityDokument5 SeitenCoek - Info The Fabric of RealityFredioGemparAnarqiNoch keine Bewertungen

- New Features in IbaPDA v7.1.0Dokument39 SeitenNew Features in IbaPDA v7.1.0Miguel Ángel Álvarez VázquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fundamentals Writing Prompts: TechnicalDokument25 SeitenFundamentals Writing Prompts: TechnicalFjvhjvgNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pipe Clamp For Sway Bracing TOLCODokument1 SeitePipe Clamp For Sway Bracing TOLCOEdwin G Garcia ChNoch keine Bewertungen

- Science BDokument2 SeitenScience BIyer JuniorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Como Desarmar Sony Vaio VGN-FE PDFDokument14 SeitenComo Desarmar Sony Vaio VGN-FE PDFPeruInalambrico Redes InalambricasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ex450-5 Technical DrawingDokument12 SeitenEx450-5 Technical DrawingTuan Pham AnhNoch keine Bewertungen

- F3 Chapter 1 (SOALAN) - RespirationDokument2 SeitenF3 Chapter 1 (SOALAN) - Respirationleong cheng liyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Watchgas AirWatch MK1.0 Vs MK1.2Dokument9 SeitenWatchgas AirWatch MK1.0 Vs MK1.2elliotmoralesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Testing, Adjusting, and Balancing - TabDokument19 SeitenTesting, Adjusting, and Balancing - TabAmal Ka100% (1)

- Sentinel Visualizer 6 User GuideDokument227 SeitenSentinel Visualizer 6 User GuideTaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lab Assignment - 2: CodeDokument8 SeitenLab Assignment - 2: CodeKhushal IsraniNoch keine Bewertungen

- CSS Lab ManualDokument32 SeitenCSS Lab ManualQaif AmzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992Dokument58 SeitenFiberglass Fire Endurance Testing - 1992shafeeqm3086Noch keine Bewertungen

- Narayana Xii Pass Ir Iit (2023 24) PDFDokument16 SeitenNarayana Xii Pass Ir Iit (2023 24) PDFRaghav ChaudharyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Java Programming ReviewerDokument90 SeitenIntroduction To Java Programming ReviewerJohn Ryan FranciscoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Zener Barrier: 2002 IS CatalogDokument1 SeiteZener Barrier: 2002 IS CatalogabcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mbs PartitionwallDokument91 SeitenMbs PartitionwallRamsey RasmeyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Highway Design ProjectDokument70 SeitenHighway Design ProjectmuhammedNoch keine Bewertungen

- How Convert A Document PDF To JpegDokument1 SeiteHow Convert A Document PDF To Jpegblasssm7Noch keine Bewertungen

- ITECH1000 Assignment1 Specification Sem22014Dokument6 SeitenITECH1000 Assignment1 Specification Sem22014Nitin KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Solution To QuestionsDokument76 SeitenSolution To QuestionsVipul AggarwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tutoriales Mastercam V8 6-11Dokument128 SeitenTutoriales Mastercam V8 6-11Eduardo Felix Ramirez PalaciosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Fitting Fundamentals: For SewersDokument21 SeitenFitting Fundamentals: For SewersLM_S_S60% (5)

- Entropy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics Disorder and The Unavailability of Energy 6Dokument14 SeitenEntropy and The Second Law of Thermodynamics Disorder and The Unavailability of Energy 6HarishChoudharyNoch keine Bewertungen