Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Why Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 2

Hochgeladen von

Jagganath VishwamitraOriginaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Why Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 2

Hochgeladen von

Jagganath VishwamitraCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

144 BUDDHIST STUDIES

Contrast this situation with that of the Jainas, whose major sects,

though only two in number, were from almost the earliest times

completely estranged.

12

Digambaras rejected the validity of nearly

all texts in the Svetambara canon and simply produced their own

secondary scriptures. The definition of conduct suitable to a monk,

moreover, was an issue of such magnitude that Digambaras viewed

Svetambara clerics as nothing more than advanced lay disciples.

Members of these two schools have traditionally not set foot in

each other's temples, and it is indeed only very recently that even

the most tentative Digambara-Svetambara dialogue has been ini-

tiated. It is fair to say, then, that the divisiveness associated with

sectarianism was much more severe amongJainas than among the

Buddhists; such divisiveness cannot, therefore, reasonably be sug-

gested as central to the downfall of Buddhism in India.

We now come to the most important and complex of the issues

raised by Mitra, that of the Buddhists' failure to pay sufficient

attention to their laity. This tendency seems to have been appar-

ent from an extremely early period, for the very term "Buddhist"

itself generally referred only to those who had actually left the

household and taken up the yellow robes of the mendicant. While

there certainly existed large numbers of lay people who supported

Buddhism, there seems to have been no clearly defined set of

criteria (vows, social codes, modes of worship, etc.) whereby these

individuals could be identified as belonging to a separate and

unique group within the larger society. WhereasJaina clerics were,

according to canonical evidence, always closely involved with their

lay people, their Buddhist counterparts tended to remain aloof

from all non-mendicants. The Jainas moreover, eventually pro-

duced some fifty texts on conduct proper to a Jaina lay person

(.fravaluicara),13 while the Buddhists, as far as we know, managed

only one (and that not until the eleventh century) .14 There can

be little doubt, then, that the sense of religious participation or

identification felt by the Buddhist lay community was often a weak

one at best. This situation probably goes far towards explaining

the lack of any "grass-roots" revival once the trappings of the

monastic establishment, viz., the great university centres, had been

destroyed.

Serious as their neglect of the need for lay involvement was,

the Buddhists committed an even greater error by failing to re-

spond meaningfully to the threat posed by the waves of bhakti that

DISAPPEARANCE OF BUDDlllSM AND TIlE SURVIVAL OF ]AINISM 145

swept across India from the fourth or fifth century onwards. The

popularity of the various Hindu devotional cults, and particularly

of those associated with RaIna and must have engendered

a great many lay defections from the Buddhist ranks. This prob-

lem was compounded by the depiction of the Buddha himself. in

the Mahiibhiirata, certain Purii1}as, and Jayadeva's Gitagovinda, as

nothing more than another avatiira of Buddhist monks

were perhaps unaware of the grave dangers represented by these

developments; not a single extant text shows any attempt either

to assimilate the popular Hindu deities into Buddhist mythology

or to refute the notion of Buddha as avatiira. The latter point was

perhaps most crucial, for by their very silence Buddhist writers

seemed to lend tacit support to the Hinduization of their founder;

this process certainly contributed to the undermining of whatever

sense of uniqueness the laity may have felt.

The response of the Jainas to similar pressures was markedly

different. They attempted to counteract Hindu suggestions (such

as those which survive in the Bhiigavatapuriir,ta) 16 that their

first Tirthankara, had been an incarnation of by attacking

the "divine" status of himself, particularly through a criti-

cism of the immoral behaviour shown by the avatiiras.

17

More

important, they produced entire alternate versions of the

Riimiiyar,ta18 and Mahiibhiirata,19 wherein RaIna and were

depicted as worldly Jaina heroes subject to the laws of Jain a ethics.

RaIna, for instance, does not kill RavaQ.a in the Jaina rendition of

the tale; this deed is instead performed by his brother

and RaIna is reborn in heaven for his strict observance of ahi1flSii.

Such a transformation was not possible for whose deeds of

violence and treachery were too numerous to cover up; thus, he

is depicted as going to hell for a long period after his earthly

death. The point here is that the Jainas sought to outflank the

bhakti movement by taking its main cult-figures as their own, while

placing these figures in a uniquely Jaina context.

This effort. together with the careful attention to lay conduct

referred to above, makes it clear that Jainas were much more

concerned with maintaining the internal cohesion of their lay

than were the Buddhists. It is tempting to aSsume that

III this fact we have found the key distinction between these two

traditions, the fundamental element in terms of which the demise

of one and survival of the other may be explained. Closer exam-

146 BUDDHIST STUDIES

ination of Jaina history, however, calls such an assumption into

question, for it seems that even the most extreme measures un-

dertaken to hold the laity together were not in themselves crucial

to the ultimate fate of the community.

We have already seen the accommodation of Hindu elements

with reference to bhallti; this tendency was carried much further

by Digambaras of the Karnataka region, who introduced, for ex-

ample, a set of saT{lSkiiras (worldly rituals, e.g., those pertaining to

birth, weddings, death, etc.) virtually indistinguishable from those

of the surrounding Hindu majority.20 While this certainly consti-

tuted "paying attention to the laity", it failed to prevent a serious

decline in the overall strength of Jaina society in the South.

Svetfunbaras and Digambaras of the North, on the other hand,

resorted to very few such measures, and yet remained, relatively

prosperous.

It will be apparent that all of the "explanations" thus far of-

fered for the decline of Buddhism, whether referring to external

pressures or to inherent structural weaknesses, reflect a purely

socia-historical perspective. Having found each of these theories

wanting in some degree, particularly in their ability to explain the

divergent fates of Buddhism andJainism, we should perhaps tum

our attention away from strictly social issues and focus instead

upon the area of doctrine. Here, one suspects, may be found

within Buddhism some element that rendered it uniquely suscep-

tible to certain of the destructive influences discussed above.

The impact of Buddhist:Jaina differences over the existence of

a soul, in terms of the greater or lesser degree of Hindu hostility

resulting therefrom, has already been considered. Probably, both

heterodox traditions were equally subject to direct orthodox ag-

gression. It must, therefore, be asked which of them was more

doctrinally open to the force of Hindu sabotage, the insidious wean-

ing away of lay support by absorption of heterodox beliefs and

cults into the Hindu sphere. In this connection. one is immediate-

ly struck by the Mahayana Buddhist doctrine of the heavenly

bodhisattvas, a class of exalted beings having absolutely no counter-

part inJaina belief. The origin ofthis doctrine. which asserted the

existence of numerous figures who had attained the enlighten-

ment of the Buddha and yet chose to remain forever in the saT{lSo:ric

realm, is not entirely clear. On the philosophical level, it probably

developed out of dissatisfaction with the earlier notion of the

DISAPPEARANCE OF BUDDHISM AND 1HE SURVIVAL OF JAINISM 147

arhats, individuals whose apparent personal attainment of

seemed to conflict with the fundamental tenet of no-self. More to

the point of the present discussion, the heavcnly bodhisattvas may

well have represented an attempt to provide some outlet for the

devotional needs of the Buddhist laity. These beings, howevcr,

were conceived of in such a way that the very fact of their enor-

mous popularity worked for, rather than against, the destruction

of Buddhism in India. This took place because the great bodhisattvas

were described as completely supramundane by nature; rather

than providing a human model of struggle and attainment, they

became virtual gods, who dispensed worldly boons and even spiri-

tual grace in a manner not unlike that of the Hindu deities. At

last, the place of the historical Buddha himself was functionally

usurped by these figures; although the Buddha remained nomi-

nally the most hallowed of beings, the bulk of popular interest

and devotion was centred not upon him but upon the great

bodhisattvas, especially Maiijusri and Avalokiteiivara.

21

While Jainas also allowed certain non-human figures to playa

part in their rituals, these were always limited to mere spirits

who were of lower status than Jaina mendicants. The

functioned as "guardians" of the holy shrines of the

TirthaiJ.karas; no great divinities on the Hindu model ever gained

legitimacy in either Jaina doctrine or worship. Thus, there was

little common ground to support the develapment of a subversive

synthesis with Hindu belief and practice. By embracing the nobon

of the heavenly bodhisattvas, however, Buddhism laid itself open to

precisely this sort of synthesis, particularly with the powerful Natha

cult of the tantric Saivite tradition. It was this fact, we believe, that

finally made the essential difference in the respective abilities of

Jainism and Buddhism to survive.

That various Buddhist temples fell into the hands of Hindu

groups is well known; notable examples are the shrines at Bodh-

gaya and Saranath, returned to Buddhist control only in modern

times.

22

What has remained obscure, however, is the exact sequence

of developments whereby such Hindu appropriation took place.

Certain little-known discoveries by the late Indian historian M.

Govinda Pai cast great light upon this question, and also provide

material in direct support of our contention that Buddhism was

subverted by the cult of the heavenly bodhisattvas.

25

In the suburbs

of Mangalore, a city in southern Karnataka, stands a Saivite temple

148 BUDDHIST STUDIES

known as Kadri-Maiijunatha; "Maiijunatha" designates the Siva-

ling a enshrined therein. Now, although Siva is commonly referred

to by titles terminating in "niitha" (e.g., Somanatha, Oxpkaranatha,

Kcdaranatha, ViSvanatha), this particular name "Maiijunatha" is

nowhere else attested as a proper epithet of the god. Intrigued by

this strange fact, Pai undertook to work out a chronological his-

tory of the temple in question. He found, first of all, that it had

once been a Buddhist monastery and temple called Kadarika-vihara;

within the shrine room stands an image of the Buddha. More

important, from our point of view, is the additional presence

therein ofa beautiful bronze image of the bodhisattvaAvalokiteSvara,

also called LokeSvara%4. An inscription at the base of the LokeSvara

image credits its establishment to one king Kundavarma of the

Alupa dynasty, stating that "Kundavdrma, the Alupa king. a great

devotee of Biilacandrasikhiima1Ji ('he who has the crescent moon

as his crest:iewel,' i.e. Siva), consecrated the image of Lord

LokeSvara in this pleasant vihiira called Kadarika, four thousand

one hundred and sixty-eight years after KaIiyuga" (i.e., 1068 A . D . . 2 . ~

The interesting point here is that an image of Lokdvara should

have been erected in a Buddhist temple by a king who was de-

voted to Siva. Clearly it was not the Buddha who was being wor-

shipped, but a bodhisattva who had in some way been integrated

with Siva.

Concerning the identification of LokeSvara with AvalokiteSvara.

see B. Bhattacarya, The Indian Buddhist Iconography, Calcutta, 1958,

Chapter 4. Also in this connection, compare the antelope skin

appearing on the image above with that of the Sanchi

AvalokiteSvara (ninth century). (The latter figure is discussed by

John Irwin in the Victoria & Albert Museum Yearbook, 1973.)

It is interesting to note that the Kadri LokeSvara image has not

been mentioned either by Irwin or by Marie-Therese de Mallman

in her book Introduction a ['etude d'AvalokiteSvara, Paris, 1948. Pai

has shown, further, that Lokesvara was identified with

Matsyendranatha, a Saivite saint said to have become divine by

attaining oneness with Sakti.26 Numerous caves in the vicinity of

Kadri are dedicated to ascetics of the Natha order which this saint

established, and an image of Matsyendranatha himself (identified

by the mark of a fish) adorns the outer wall of the "Kadarika-

vihara" temple. Considering the name "Maiijunatha" in light of all

this information, Pai concluded that the vihiira was originally a

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- Why Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 3Dokument5 SeitenWhy Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 3Jagganath VishwamitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Why Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 1Dokument5 SeitenWhy Jainism Survived in India and Buddhism Didnot? Part 1Jagganath VishwamitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- Archaeological Discoveries at LumbiniDokument3 SeitenArchaeological Discoveries at LumbiniJagganath VishwamitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The History of Hindu India - A Textbook of All AgesDokument66 SeitenThe History of Hindu India - A Textbook of All AgesJagganath VishwamitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- Summaries On Hindu DarshanasDokument143 SeitenSummaries On Hindu DarshanasJagganath VishwamitraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- 2006 Yamaha MotoGP YZR-M1 Technical PresentationDokument23 Seiten2006 Yamaha MotoGP YZR-M1 Technical PresentationJagganath Vishwamitra100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

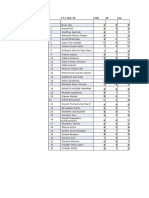

- List of Guides - Finance SpecialisationDokument4 SeitenList of Guides - Finance SpecialisationSuyash PrakashNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- 8 IG A - CT1 - CompiledDokument2 Seiten8 IG A - CT1 - CompiledHaritika ChhatwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- Brihadeeswarar TempleDokument4 SeitenBrihadeeswarar TempleJaiprakash SekarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- RAIN GUARD With High ThiknessDokument3 SeitenRAIN GUARD With High ThiknessSantosh Kumar PatnaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Nāda YogaDokument14 SeitenNāda YogaSean GriffinNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- 00sanskrit LettersDokument39 Seiten00sanskrit LettersAchuta GotetiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Yoga Vasistha Part IDokument636 SeitenYoga Vasistha Part Iinnerguide100% (4)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- New Age-Marsha WestDokument42 SeitenNew Age-Marsha WestFrancis LoboNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sky GodsDokument11 SeitenSky GodsmehNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Bank of India Job DetailsDokument20 SeitenBank of India Job DetailsVigneshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Yes We Can, But WHV We Cannot ?" & How We Can ? Written by Nanubhai NaikDokument151 SeitenYes We Can, But WHV We Cannot ?" & How We Can ? Written by Nanubhai NaikNanubhaiNaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aims Members Directory-2014-15Dokument61 SeitenAims Members Directory-2014-15AkshayNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- KrazDokument12 SeitenKrazNina Elezovic SimunovicNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aparaajita VidyaDokument11 SeitenAparaajita VidyaGopal VenkatramanNoch keine Bewertungen

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Rainage Ystem: Geography - Part IDokument11 SeitenRainage Ystem: Geography - Part IChithra ThambyNoch keine Bewertungen

- National Highways and Their LengthDokument12 SeitenNational Highways and Their LengthManu ShrivastavaNoch keine Bewertungen

- HanumanDokument19 SeitenHanumanLakshanmayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sri Rudram Occurs in Krishna Yajur Veda in The Taithireeya Samhita in The Fourth and Seventh ChaptersDokument28 SeitenThe Sri Rudram Occurs in Krishna Yajur Veda in The Taithireeya Samhita in The Fourth and Seventh Chaptersravi_na100% (1)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- Vedic MathsDokument6 SeitenVedic MathsashankarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aurangzeb Era Sarvani RevoltDokument18 SeitenAurangzeb Era Sarvani Revoltpramodbankhele3845Noch keine Bewertungen

- Yajurveda Kaalai Sandhyaavandanam: in Sanskrit, Tamil and English (With Instructions in English)Dokument14 SeitenYajurveda Kaalai Sandhyaavandanam: in Sanskrit, Tamil and English (With Instructions in English)Logesh prasanna channelNoch keine Bewertungen

- VedaDokument11 SeitenVedanaripooriNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- List of Kannada-Language Films PDFDokument24 SeitenList of Kannada-Language Films PDFtarunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Srikakulam 12Dokument93 SeitenSrikakulam 12sreenivasa rao ganapatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sri Sri Durga Saptshati (Sanskrit - Hindi)Dokument241 SeitenSri Sri Durga Saptshati (Sanskrit - Hindi)Mukesh K. Agrawal62% (13)

- Financial Year Creation 2019-2020Dokument1 SeiteFinancial Year Creation 2019-2020praveen NaikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kodungallur Bhagavathy TempleDokument1 SeiteKodungallur Bhagavathy TemplePSGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Coimbatore District Abstract For Road Surface Details FormatsDokument81 SeitenCoimbatore District Abstract For Road Surface Details FormatsMEP TECHNoch keine Bewertungen

- History and Development of PrisonsDokument6 SeitenHistory and Development of PrisonsGopal Pottabathni100% (1)

- Id Stateid Statename Unitcode Unitname Districtid Districtname ConstcodeDokument41 SeitenId Stateid Statename Unitcode Unitname Districtid Districtname Constcodesakshi sakshiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)