Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

People v. Evaristo (Plain View Doctrine Search Incidental To Lawful Arrest)

Hochgeladen von

kjhenyo218502Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

People v. Evaristo (Plain View Doctrine Search Incidental To Lawful Arrest)

Hochgeladen von

kjhenyo218502Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

People v.

Evaristo

G.R. No. 93828, December 11, 1992

FACTS:

A contingent of peace officers, while on routine patrol duty, heard successive bursts of gunfire

and proceeded to the approximate source of the same where they came upon one Barequiel Rosillo

who was firing a gun into the air.

Seeing the patrol, Rosillo ran to the nearby house of appellant Evaristo, prompting the peace

officers to pursue him. Upon approaching the immediate perimeter of the house, the patrol chanced

upon the slightly inebriated appellants, Evaristo and Carillo. Inquiring as to the whereabouts of Rosillo,

the officers were told that he had already escaped through a window of the house.

Sgt. Vallarta immediately observed a noticeable bulge around the waist of Carillo who, upon

being frisked, admitted the same to be a .38 revolver. After ascertaining that Carillo was neither a

member of the military nor had a valid license to possess the said firearm, the gun was confiscated and

Carillo invited for questioning.

As the patrol was still in pursuit of Rosillo, Sgt. Romeroso sought Evaristo's permission to scour

through the house, which was granted. In the sala, he found, not Rosillo, but a number of firearms and

paraphernalia supposedly used in the repair and manufacture of firearms, all of which, thereafter,

became the basis for the present indictment against Evaristo. Evaristo was, then, found guilty of illegal

possession of firearms but contended that the seizure of the evidence is inadmissible because it was not

authorized by a valid warrant.

ISSUE: WON the search and seizure of firearms from Evaristo and Carillo were valid?

RULING:

YES, they were valid.

It is to be noted that what the Constitution prohibits are unreasonable searches and seizures.

For a search to be reasonable under the law, there must, as a rule, be a search warrant validly issued by

an appropriate judicial officer. Yet, the rule that searches and seizures must be supported by a valid

search warrant is not an absolute and inflexible rule, for jurisprudence has recognized several

exceptions to the search warrant requirement. Among these exceptions is the seizure of evidence in

plain view. Thus, it is recognized that objects inadvertently falling in the plain view of an officer who

has the right to be in the position to have that view, are subject to seizure and may be introduced in

evidence.

The records in this case show that Sgt. Romerosa was granted permission by the appellant

Evaristo to enter his house. The officer's purpose was to apprehend Rosillo whom he saw had sought

refuge therein. Therefore, it is clear that the search for firearms was not Romerosa's purpose in

entering the house, thereby rendering his discovery of the subject firearms as inadvertent and even

accidental.

With respect to the firearms seized from the appellant Carillo, the Court sustains the validly of

the firearm's seizure and admissibility in evidence, based on the rule on authorized warrantless arrests.

Section 5 (b), Rule 113 of the 1985 Rules on Criminal Procedure provides that a peace officer or a private

person may, without a warrant, arrest a person when an offense has in fact just been committed, and

he has personal knowledge of facts indicating that the person to be arrested has committed it.

Here, the peace officers, while on patrol, heard bursts of gunfire and this proceeded to

investigate the matter. This incident may well be within the "offense" envisioned by par. 5 (b) of Rule

113, Rules of Court. As the Court held in People of the Philippines v. Sucro, "an offense is committed in

the presence or within the view of an officer, within the meaning of the rule authorizing an arrest

without a warrant, when the officer sees the offense, although at a distance, or HEARS THE

DISTURBANCES CREATED THEREBY AND PROCEEDS AT ONCE TO THE SCENE THEREOF."

The next inquiry is addressed to the existence of personal knowledge on the part of the peace

officer of facts pointing to the person to be arrested as the perpetrator of the offense. Giving chase to

Rosillo, the peace officers, themselves, came upon the two (2) appellants who were then asked

concerning Rosillo's whereabouts. At that point, Sgt. Vallarta, himself, discerned the bulge on the waist

of Carillo. This visual observation along with the earlier report of gunfire, as well as the peace officer's

professional instincts, are more than sufficient to pass the test of the Rules. Consequently, under the

facts, the firearm taken from Carillo can be said to have been seized incidental to a lawful and valid

arrest.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- People Vs Tonog Jr.Dokument2 SeitenPeople Vs Tonog Jr.JakeDanduan100% (1)

- People v. Jayson (Villarama)Dokument1 SeitePeople v. Jayson (Villarama)Binkee VillaramaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Soriano Vs AngelesDokument2 SeitenSoriano Vs AngelesRyan SuaverdezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allado v. DioknoDokument4 SeitenAllado v. DioknoKobe Lawrence VeneracionNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Philippines Octavio Mendoza Y LandichoDokument2 SeitenPeople of The Philippines Octavio Mendoza Y LandichoKaren Joy MasapolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prudente V DayritDokument4 SeitenPrudente V DayritRon Jacob AlmaizNoch keine Bewertungen

- (People v. Salvatierra) DigestDokument2 Seiten(People v. Salvatierra) DigestitsmestephNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cruz vs. Areola, March 6, 2002 Case DigestDokument2 SeitenCruz vs. Areola, March 6, 2002 Case DigestElla Kriziana CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Philippines V. Julio Herida: Prepared By: Alyssa Mae G. CayabaDokument1 SeitePeople of The Philippines V. Julio Herida: Prepared By: Alyssa Mae G. CayabaA CybaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philippines Supreme Court Rules Search of Unit 122 IllegalDokument2 SeitenPhilippines Supreme Court Rules Search of Unit 122 IllegalDominique Vasallo100% (1)

- LCP CRIM 2 SEARCHES AND SEIZURES PEOPLE V GESMUNDODokument1 SeiteLCP CRIM 2 SEARCHES AND SEIZURES PEOPLE V GESMUNDOAbigail TolabingNoch keine Bewertungen

- The People of The Philippines v. Renante Mendez and Baby Cabagtong (G.r. No. 147671. November 21, 2002)Dokument5 SeitenThe People of The Philippines v. Renante Mendez and Baby Cabagtong (G.r. No. 147671. November 21, 2002)Ei BinNoch keine Bewertungen

- PC officers arrest unlawful; Aminnudin acquittedDokument1 SeitePC officers arrest unlawful; Aminnudin acquittedrandz1051Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sufficiency of complaint under Rule 110Dokument1 SeiteSufficiency of complaint under Rule 110chiccostudentNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Burgos DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople v. Burgos DigestFrancis Guinoo100% (5)

- People V Damaso Case DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople V Damaso Case DigestAnna Lou Keshia75% (4)

- Sanchez v. DemetriouDokument2 SeitenSanchez v. DemetriouVian O.100% (1)

- People of The Philippines v. TonogDokument2 SeitenPeople of The Philippines v. TonogJemson Ivan WalcienNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V MolinaDokument3 SeitenPeople V MolinaJul A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- 535 People vs. Samulde - 336 Scra 632 (2000)Dokument1 Seite535 People vs. Samulde - 336 Scra 632 (2000)JUNGCO, Jericho A.Noch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. Padirayon DigestDokument1 SeitePeople vs. Padirayon DigestRussell John Hipolito100% (1)

- Motion to Quash Provisional DismissalDokument3 SeitenMotion to Quash Provisional DismissalitsmestephNoch keine Bewertungen

- People of The Philippines vs. Molina and MulaDokument1 SeitePeople of The Philippines vs. Molina and MulaJohn Baja GapolNoch keine Bewertungen

- G.R. No. 120915 People Vs ARUTADokument1 SeiteG.R. No. 120915 People Vs ARUTAJoyce Sumagang Reyes100% (2)

- Mere CPP Membership Does Not Equal RebellionDokument4 SeitenMere CPP Membership Does Not Equal RebellionMIKKO100% (1)

- Warrantless Arrest and Self-Defense in People vs ManluluDokument4 SeitenWarrantless Arrest and Self-Defense in People vs ManluluDominic EmbodoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V MoleroDokument2 SeitenPeople V MolerotrishortizNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. Villarama Legal Research Plea BargainingDokument3 SeitenPeople vs. Villarama Legal Research Plea BargainingLiz Matarong BayanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Webb v de Leon - Procedural Due Process in Judicial ProceedingsDokument2 SeitenWebb v de Leon - Procedural Due Process in Judicial ProceedingsMar JoeNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs Dichoso DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs Dichoso DigestJane Jaramillo67% (3)

- PEOPLE Vs NEPOMUCENODokument2 SeitenPEOPLE Vs NEPOMUCENOEthan KurbyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Paderanga v. Drilon Bail Ruling AnalysisDokument2 SeitenPaderanga v. Drilon Bail Ruling AnalysisMayumi RellitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. CastilloDokument3 SeitenPeople vs. CastilloMaestro LazaroNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs MalasuguiDokument1 SeitePeople Vs MalasuguialchupotNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rpadilla G.R 121917Dokument4 SeitenRpadilla G.R 121917Jia SamsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- SC rules search of home without warrant unlawfulDokument2 SeitenSC rules search of home without warrant unlawfulLiz LorenzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 Go vs. CA - GR No. 101837 - Case DigestDokument2 Seiten8 Go vs. CA - GR No. 101837 - Case DigestAbigail TolabingNoch keine Bewertungen

- UY KHEYTIN Vs VILLAREAL, 42 Phil 886Dokument2 SeitenUY KHEYTIN Vs VILLAREAL, 42 Phil 886Divina Gracia HinloNoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Francisco, G.R. No. 129035 Case Digest (Criminal Procedure)Dokument5 SeitenPeople v. Francisco, G.R. No. 129035 Case Digest (Criminal Procedure)AizaFerrerEbinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs TudtudDokument2 SeitenPeople Vs TudtudRmLyn Mclnao75% (8)

- Miller Vs PerezDokument2 SeitenMiller Vs PerezAthena SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- David vs. Aquilizan (94 SCRA 707)Dokument1 SeiteDavid vs. Aquilizan (94 SCRA 707)MaeBartolome100% (1)

- People v. Compacion, G.R. No. 124442.digestDokument3 SeitenPeople v. Compacion, G.R. No. 124442.digestDominique VasalloNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sasot v. PeopleDokument2 SeitenSasot v. PeopleMaya Julieta Catacutan-Estabillo100% (1)

- Court upholds validity of graft chargesDokument2 SeitenCourt upholds validity of graft chargesSum VelascoNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V BuscatoDokument2 SeitenPeople V BuscatoGarri AtaydeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 75 People v. Tria-TironaDokument2 Seiten75 People v. Tria-TironaRostum AgapitoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Rules on Pre-Trial Witness AbsenceDokument3 SeitenSupreme Court Rules on Pre-Trial Witness AbsenceKobe Lawrence Veneracion100% (1)

- People of The Philippines v. Cesar O. Delos Reyes (G.r. No. 140657. October 25, 2004)Dokument2 SeitenPeople of The Philippines v. Cesar O. Delos Reyes (G.r. No. 140657. October 25, 2004)Ei BinNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V Burgos DigestDokument2 SeitenPeople V Burgos DigestJerome C obusanNoch keine Bewertungen

- People vs. Cabanada Admissibility of Uncounselled AdmissionsDokument1 SeitePeople vs. Cabanada Admissibility of Uncounselled AdmissionsJERICHO JUNGCONoch keine Bewertungen

- People v. Malmstedt DigestDokument3 SeitenPeople v. Malmstedt DigestJulian Velasco100% (2)

- Consequences of Failing to Inform Suspect of Rights during Custodial InterrogationDokument2 SeitenConsequences of Failing to Inform Suspect of Rights during Custodial InterrogationCarlyn Belle de Guzman50% (2)

- People vs. Nuevas G.R. No. 170233, February 22, 2007 FactsDokument2 SeitenPeople vs. Nuevas G.R. No. 170233, February 22, 2007 FactsJessamine Orioque67% (3)

- NPC v. Henson. DigestDokument2 SeitenNPC v. Henson. DigestAngelo Brian Kiks-azzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pangandaman Vs CasarDokument3 SeitenPangandaman Vs CasarHanna MapandiNoch keine Bewertungen

- People Vs Sy ChuaDokument3 SeitenPeople Vs Sy ChuaJessamine OrioqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Santiago v. Vasquez (Digest)Dokument3 SeitenSantiago v. Vasquez (Digest)Arahbells100% (3)

- People v. Cabanada: Admission During General Inquiry AdmissibleDokument2 SeitenPeople v. Cabanada: Admission During General Inquiry Admissiblejenwin100% (1)

- 4 PP v. EvaristoDokument4 Seiten4 PP v. EvaristoryanmeinNoch keine Bewertungen

- 7 Steps To Getting A Mayor's Permit - Business Registration - Full SuiteDokument13 Seiten7 Steps To Getting A Mayor's Permit - Business Registration - Full Suitekjhenyo218502100% (1)

- Dolo Causante v. Incidente - Ferro Chemicals v. Antonio M. GarciaDokument47 SeitenDolo Causante v. Incidente - Ferro Chemicals v. Antonio M. Garciakjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Dangerously Neglecting Courtroom Realities: Citing LiteratureDokument2 SeitenDangerously Neglecting Courtroom Realities: Citing Literaturekjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Article I - Name That Corporation - BusinessMirrorDokument3 SeitenArticle I - Name That Corporation - BusinessMirrorkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Inheritance Claim of Illegitimate ChildDokument11 SeitenInheritance Claim of Illegitimate Childkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Sample of Employment Contact PT EngDokument3 SeitenSample of Employment Contact PT EngjaciemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Standard Contract - HouseholdDokument3 SeitenStandard Contract - HouseholdJoshuaLavegaAbrinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Belo vs. Guevarra - A Landmark Case For Facebook Privacy in PH - Newsbytes PhilippinesDokument4 SeitenBelo vs. Guevarra - A Landmark Case For Facebook Privacy in PH - Newsbytes Philippineskjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Spes Form 5 - Employment ContractDokument1 SeiteSpes Form 5 - Employment Contractkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- MA Public Records Request GuideDokument1 SeiteMA Public Records Request Guidekjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Castillo Poli Saño v. COMELECDokument4 SeitenCastillo Poli Saño v. COMELECkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- November27 PeoplevsVelasco RemDokument4 SeitenNovember27 PeoplevsVelasco Remkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- TaxRev - CIR v. Liquigaz Philippines (A VOID FDDA Does NOT Render The Assessment Void)Dokument42 SeitenTaxRev - CIR v. Liquigaz Philippines (A VOID FDDA Does NOT Render The Assessment Void)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Political - Hermano Oil v. TRBDokument16 SeitenPolitical - Hermano Oil v. TRBkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1Rev - Garrido v. Javier (Prescriptive Period of Civil Liability Arising From Criminal Offense)Dokument5 SeitenCiv1Rev - Garrido v. Javier (Prescriptive Period of Civil Liability Arising From Criminal Offense)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Rules Conjugal Properties Not Liable for Husband's Corporate Surety AgreementDokument13 SeitenSupreme Court Rules Conjugal Properties Not Liable for Husband's Corporate Surety Agreementkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1Rev - Ayala Investment v. CA (Art. 121, Family Code)Dokument13 SeitenCiv1Rev - Ayala Investment v. CA (Art. 121, Family Code)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- CivRev2 - Samar Mining Co. v. Northern LoydDokument7 SeitenCivRev2 - Samar Mining Co. v. Northern Loydkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1Rev - Victoriano v. CA (Laches May DEFEAT Registered Owner)Dokument6 SeitenCiv1Rev - Victoriano v. CA (Laches May DEFEAT Registered Owner)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Taxrev - Cepalco v. City of CdoDokument26 SeitenTaxrev - Cepalco v. City of Cdokjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- TaxRev - BDO v. RPDokument76 SeitenTaxRev - BDO v. RPkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- TaxRev - PLDT v. City of Davao (WITHDRAWAL of Exemption From Local Franchise Tax)Dokument23 SeitenTaxRev - PLDT v. City of Davao (WITHDRAWAL of Exemption From Local Franchise Tax)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- TaxRev - Marubeni v. CIR (1989) (NON-Resident Foreign Corporation)Dokument16 SeitenTaxRev - Marubeni v. CIR (1989) (NON-Resident Foreign Corporation)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Inheritance Claim of Illegitimate ChildDokument11 SeitenInheritance Claim of Illegitimate Childkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- CA Affirms No Express Prohibition to Collate Donated PropertiesDokument5 SeitenCA Affirms No Express Prohibition to Collate Donated Propertieskjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1Rev - People v. Bayotas (Death of Accused Pending Appeal of Conviction)Dokument17 SeitenCiv1Rev - People v. Bayotas (Death of Accused Pending Appeal of Conviction)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- Civ1Rev - Nera v. Rimando (In The Presence of Subscribing Witnesses To A Will)Dokument4 SeitenCiv1Rev - Nera v. Rimando (In The Presence of Subscribing Witnesses To A Will)kjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- SpecPro - Ceruila v. DelantarDokument3 SeitenSpecPro - Ceruila v. Delantarkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- RENE A.V. SAGUISAG Vs EXECUTIVE SECRETARY PA QUITO N. OCHOA, JR. (G.R. No. 212426)Dokument118 SeitenRENE A.V. SAGUISAG Vs EXECUTIVE SECRETARY PA QUITO N. OCHOA, JR. (G.R. No. 212426)Armstrong BosantogNoch keine Bewertungen

- Specpro - Ilusorio V Ilusorio-BildnerDokument6 SeitenSpecpro - Ilusorio V Ilusorio-Bildnerkjhenyo218502Noch keine Bewertungen

- TX Commission On Law Enforcement - Training and Education Records For STEPHANIE BRANCH, DART PoliceDokument6 SeitenTX Commission On Law Enforcement - Training and Education Records For STEPHANIE BRANCH, DART PoliceAvi S. AdelmanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Joe D. Weddington v. United States of America, Third-Party Clifford G. Bevins, Third-Party, 762 F.2d 1013, 3rd Cir. (1985)Dokument3 SeitenJoe D. Weddington v. United States of America, Third-Party Clifford G. Bevins, Third-Party, 762 F.2d 1013, 3rd Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reviewer - Article 35-38,45-47,65-68,70-73Dokument19 SeitenReviewer - Article 35-38,45-47,65-68,70-73Jani MisterioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Beck v. Feneis - Document No. 4Dokument2 SeitenBeck v. Feneis - Document No. 4Justia.comNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art 267 Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention: (CITATION Lui /L 13321)Dokument3 SeitenArt 267 Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention: (CITATION Lui /L 13321)vincent nifasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Criminal Law: Concept of Criminal ConspiracyDokument3 SeitenCriminal Law: Concept of Criminal ConspiracyAnanyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hammond Probation Violation (Full Text Messages Included)Dokument4 SeitenHammond Probation Violation (Full Text Messages Included)WTVR CBS 6Noch keine Bewertungen

- Flores Vs Ombudsman (GR No. 136769) Sept. 17, 2002Dokument2 SeitenFlores Vs Ombudsman (GR No. 136769) Sept. 17, 2002Dean BenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digested CasesDokument4 SeitenDigested CasesKenny Robert'sNoch keine Bewertungen

- Home Defender Magazine - Spring 2014Dokument132 SeitenHome Defender Magazine - Spring 2014guilhasbr100% (4)

- Supreme Court Rules Regional Trial Court Has Jurisdiction Over Bounced Dollar Check CaseDokument4 SeitenSupreme Court Rules Regional Trial Court Has Jurisdiction Over Bounced Dollar Check CaseLou Ann AncaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- That Advantage Be Taken by The Offender of His PUBLIC POSITIONDokument7 SeitenThat Advantage Be Taken by The Offender of His PUBLIC POSITIONJonah Micah CemaniaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Most Wanted Property Crime Offenders June 2010Dokument1 SeiteMost Wanted Property Crime Offenders June 2010Albuquerque JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aratea v. ComelecDokument2 SeitenAratea v. ComelecronaldNoch keine Bewertungen

- SPL Digest CasesDokument10 SeitenSPL Digest CasesNombs NomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supreme Court Authority Over JudgesDokument47 SeitenSupreme Court Authority Over JudgesJezen Esther PatiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Remedial Digest 26 31Dokument13 SeitenRemedial Digest 26 31Limberge Paul CorpuzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Prison Reforms in IndiaDokument11 SeitenPrison Reforms in IndiaAVINASH THAKURNoch keine Bewertungen

- Comparative Analysis of Cyber-Crime LawsDokument17 SeitenComparative Analysis of Cyber-Crime LawsFemi Erinle100% (2)

- Vda. de Ramos vs. Court of AppealsDokument2 SeitenVda. de Ramos vs. Court of AppealsKaye Mendoza100% (2)

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDokument5 Seiten(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNoch keine Bewertungen

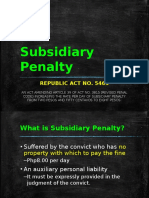

- Subsidiary PenaltyDokument13 SeitenSubsidiary PenaltyJezen Esther Pati100% (2)

- Dessini CaseDokument2 SeitenDessini CaseEman CipateNoch keine Bewertungen

- Police Dept DirectoryDokument7 SeitenPolice Dept DirectoryyashNoch keine Bewertungen

- Espano V CA, 288 Scra 558Dokument11 SeitenEspano V CA, 288 Scra 558MykaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Research Grave Coercion2Dokument9 SeitenResearch Grave Coercion2Nyl AnerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Literature Review of Policing Intelligence and Homeland SecurityDokument3 SeitenLiterature Review of Policing Intelligence and Homeland SecurityJason SmithNoch keine Bewertungen

- CrimPro HW 6:8:17 (Case Digest) TPDokument2 SeitenCrimPro HW 6:8:17 (Case Digest) TPOlenFuerteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lansang V GarciaDokument6 SeitenLansang V GarciaDanielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Malayan Law Journal Reports 2000 Volume 7 Case Summary on Alienation of State Land and Payment of Royalty for Forest ProduceDokument8 SeitenMalayan Law Journal Reports 2000 Volume 7 Case Summary on Alienation of State Land and Payment of Royalty for Forest ProduceLenny JMNoch keine Bewertungen