Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Role of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in The Early Management of Acute Gallbladder Disease

Hochgeladen von

Horacio Chacon0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

17 Ansichten6 SeitenThis study evaluated the role of laparoscopic surgery in the early management of acute gallbladder disease in a single large UK teaching hospital. 385 patients with gallstone disease (243 acute biliary pain, 142 acute cholecystitis) and 15 with acalculous disease were identified.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

British Journal of Surgery Volume 92 Issue 5 2005 [Doi 10.1002%2Fbjs.4831] W. K. Peng; Z. Sheikh; S. J. Nixon; S. Paterson-Brown -- Role of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in the

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThis study evaluated the role of laparoscopic surgery in the early management of acute gallbladder disease in a single large UK teaching hospital. 385 patients with gallstone disease (243 acute biliary pain, 142 acute cholecystitis) and 15 with acalculous disease were identified.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

17 Ansichten6 SeitenRole of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in The Early Management of Acute Gallbladder Disease

Hochgeladen von

Horacio ChaconThis study evaluated the role of laparoscopic surgery in the early management of acute gallbladder disease in a single large UK teaching hospital. 385 patients with gallstone disease (243 acute biliary pain, 142 acute cholecystitis) and 15 with acalculous disease were identified.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 6

Original article

Role of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in the early management

of acute gallbladder disease

W. K. Peng, Z. Sheikh, S. J. Nixon and S. Paterson-Brown

Department of Clinical and Surgical Sciences (Surgery), Royal Inrmary of Edinburgh, Little France Crescent, Edinburgh EH16 4SA, UK

Correspondence to: Mr S. Paterson-Brown (e-mail: spb@doctors.org.uk)

Background: This study evaluated the role of laparoscopic surgery in the early management of acute

gallbladder disease in a single large UK teaching hospital.

Methods: Details of all emergency admissions for acute gallbladder disease from January 2000 to

December 2001 were identied and additional information from the hospital records was reviewed

retrospectively.

Results: Three hundred and eighty-ve patients with gallstone disease (243 acute biliary pain, 142 acute

cholecystitis) and 15 with acalculous disease were identied. The conversion rate was higher during early

laparoscopic surgery for acute calculous cholecystitis than in operations for acute biliary pain (19 versus

4 per cent; P = 0002). In patients with acute calculous cholecystitis the conversion rate was signicantly

lower in operations within 48 h of admission (one of 26) than when surgery was delayed beyond 48 h (14

of 52) or subsequently carried out electively (seven of 21) (P = 0014). Elective surgery for previous acute

cholecystitis was associated with a higher conversion rate (seven of 21 patients) than elective surgery for

biliary pain (three of 65) (P = 0002).

Conclusion: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute calculous cholecystitis should be performed, where

possible, within the rst 48 h of admission.

Paper accepted 11 August 2004

Published online 18 March 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.bjs.co.uk). DOI: 10.1002/bjs.4831

Introduction

The value of early cholecystectomy for acute calculous

cholecystitis was well established in the prelaparoscopic

era

1,2

and early laparoscopic intervention has subsequently

been shown to provide an improved outcome

26

. In

spite of this, many hospitals in the UK do not

have a policy of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy

for acute gallbladder disease. This may partly be

related to ongoing concerns that conversion rates

are higher in the acute setting, partly to the fact

that not all emergency general surgeons are skilled

in laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and also to resource

restrictions in many hospitals regarding early access to

theatre for patients considered not to require urgent

surgery.

Conversion rates for early laparoscopic cholecys-

tectomy in patients with acute cholecystitis range

from 5 to 30 per cent, but optimal timing for early

operation is difcult to assess because most reports

did not compare surgery at different time inter-

val within the same admission, case mix differences

and patient selection. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for

an acutely inamed gallbladder is technically more

demanding than surgery for acute biliary pain with-

out inammation (biliary colic), and the time inter-

val from admission to surgery may affect conversion

rates

79

.

Apart from obscure anatomy and bleeding, the reasons

for conversion to open surgery relate to the presence of

inammation in the acute setting and to adhesions in the

elective setting. Although the decision to convert should

not be considered as a complication, as the overall success-

ful and safe completion of the operation is the ultimate

goal, it would be useful to identify the circumstances under

which laparoscopic cholecystectomy might have the best

chance of successful completion. This study examined the

management of all patients admitted to the Royal Inrmary

of Edinburgh with acute gallbladder disease over 2 years

to evaluate the outcome of early laparoscopic surgery.

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Early management of gallbladder disease 587

Patients and methods

Details of all patients admitted to the general surgical unit

of Edinburgh Royal Inrmary are recorded prospectively

using the Lothian Surgical Audit system. A total of

400 patients having an emergency admission for acute

gallbladder disease were identied between January 2000

and December 2001. This system records patients

diagnoses and operative details with specic codes, and

includes free text for the operation notes, discharge

summary and any clinic letters. Additional information

such as ultrasonography reports, blood results and

histological ndings were retrieved retrospectively from

patients notes or the hospital information system.

The diagnosis of acute calculous cholecystitis in

patients operated on during an acute admission was

based on histological evidence of acute inammatory

cells. When the patient did not have early surgery,

the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis was based on

clinical features (right upper quadrant tenderness with

or without fever) and ultrasonographic conrmation of

gallstones, with either ultrasonographic features suggestive

of inammation (gallbladder wall thickness of more than

3 mm, oedematous wall, emphysematous wall, gallbladder

distension, pericholecystic uid, positive sonographic

Murphys sign) and/or leucocytosis greater than11 10

9

/l.

The diagnosis of acute biliary pain was made if

ultrasonographic, laboratory or histological ndings did

not reveal any sign of acute inammation. Bacteriological

specimens were not collected routinely at operation.

Patients with gallstone pancreatitis and gallstone ileus were

excluded from the study.

Statistical analysis

The Wilcoxon sum-of-rank test was used to analyse two-

sample unpaired quantitative data, and three-sample data

were analysed with the non-parametric Kruskal Wallis

test. Qualitative data were analysed using Fishers exact

(two-tailed P value) test. P < 0050 was considered

statistically signicant.

Results

Of the 400 patients identied, 385 (962 per cent) had acute

gallstone disease and 15 (38 per cent) had acute acalculous

cholecystitis. Some 142 (369 per cent) of the patients with

acute gallstone disease had acute cholecystitis and 243

(631 per cent) had acute biliary pain.

Management and outcome

Of the 142 patients (85 women; 599 per cent) with acute

calculous cholecystitis, 89 (627 per cent) had cholecys-

tectomy during the same acute admission. Laparoscopic

cholecystectomy was attempted in 78 patients (88 per cent)

and 11 (12 per cent) had open cholecystectomy. Percuta-

neous cholecystostomy was performed in four patients who

did not have early cholecystectomy. In total, 53 patients

were discharged home without early surgery, of whom

three had follow-up in another hospital, 21 proceeded to

elective surgery, 18 remained well and did not undergo

surgery, and 11 required further emergency admission

(three with acute cholecystitis, seven with acute biliary

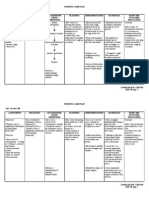

pain and one with gallstone pancreatitis). Table 1 shows the

histological ndings in patients who had early surgery, and

Table 2 lists the ultrasonographic and laboratory ndings

in patients who were discharged without early surgery.

Two elderly patients who were deemed unt for chole-

cystectomy because of signicant co-morbidity died from

multiorgan failure.

Of the 243 patients (164 women; 675 per cent)

with acute biliary pain, 87 (358 per cent) had early

cholecystectomy during the same acute admission; 85

Table 1 Histological ndings in patients with acute calculous

cholecystitis who underwent early surgery

No. of patients

(n = 89)

Acute inammation 63 (71)

Gangrene 17 (19)

Empyema 5 (6)

Gangrene with empyema 2 (2)

Perforated gallbladder 2 (2)

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Table 2 Ultrasonographic and laboratory ndings in patients with

acute calculous cholecystitis who were discharged without early

surgery

No. of patients

(n = 53)

Gallbladder wall thickened >3 mm 37 (70)

Oedematous wall 11 (21)

Pericholecystitic uid 5 (9)

Positive sonographic Murphys sign 3 (6)

Sludge within gallbladder 2 (4)

Distended gallbladder 1 (2)

Emphysematous wall 1 (2)

Intrahepatic abscess related to cholecystitis 1 (2)

Leucocytosis 48 (91)

Values in parentheses are percentages.

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

588 W. K. Peng, Z. Sheikh, S. J. Nixon and S. Paterson-Brown

had attempted laparoscopic cholecystectomy and two

had an open operation owing to signicant previous

abdominal surgery. Seventeen patients discharged without

undergoing surgery were followed up in other hospitals,

66 proceeded to elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy

(65 laparoscopic, one open), 53 remained well with

conservative management and 20 required a further

emergency admission. There was no death in this group.

Of patients who did not have an early operation, 20

(128 per cent) of 156 with acute biliary pain and 11

(21 per cent) of 53 with acute cholecystitis required a

further emergency readmission (P = 0181).

Of the 15 patients (seven women) with acute acalculous

cholecystitis, six had surgery during the same acute

admission (three attempted laparoscopic and three open

cholecystectomies). Percutaneous cholecystostomy was

performed in one patient who did not have early

cholecystectomy. Nine patients were discharged; three

proceeded to elective surgery at a later date, ve remained

well with conservative management, and one required a

further emergency admission. There were three deaths in

this group of patients, two from septic shock and one from

pulmonary embolism (one of these deaths occurred after

elective surgery).

Effect of age

The mean age of patients with acute calculous cholecystitis

was 58 (range 1499) years and that of patients with

acute biliary pain was 55 (range 1695) years (P 0097).

Patients with acute acalculous cholecystitis had a mean age

of 62 (range 3297) years. Patients operated on at the rst

admission for acute calculous cholecystitis (P 0002) or

acute biliary pain (P 00003) were signicantly younger

than whose in whom surgery was deferred (Table 3).

Presence of common bile duct stones

Overall 11 (77 per cent) of 142 patients with acute

calculous cholecystitis and 40 (165 per cent) of 243

with acute biliary pain were found to have common

Table 3 Patient age and timing of surgery

Mean (range) age (years)

Early surgery Discharged P*

Acute calculous cholecystitis 54 (1488) 64 (2799) <0002

Acute biliary pain 49 (1686) 58 (1995) <0001

P* <005 <005

*Wilcoxon sum-of-rank test.

bile duct stones. Thirty-two patients in whom there

was a high suspicion of choledocholithiasis (signicantly

abnormal liver function test results and/or an abnormal

biliary tree on ultrasonography) underwent preoperative

endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP).

The remaining 19 patients had selective intraoperative

cholangiography according to clinical data, operative

ndings and consultant preference; the methods of

stone retrieval were postoperative ERCP (11 patients),

laparoscopic exploration of the common bile duct with

choledochoscopy (four), conversion to open surgery (two),

and in two patients the small lling defect found on

cholangiography was left alone.

Laparoscopic conversion rate

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was converted to open

surgery in 15 (19 per cent) of 78 patients having early

operation for acute cholecystitis, compared with three

(4 per cent) of 85 patients with acute biliary pain

(P = 0002). One of three patients undergoing early

laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acalculous cholecystitis

required conversion. After non-operative early treatment

and subsequent readmission for elective cholecystectomy,

the conversion rate was 33 per cent (seven of 21) in patients

with previous acute calculous cholecystitis compared with

5 per cent (three of 65) in those with previous acute biliary

pain (P = 0002). There were no conversions in the three

patients who had elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy

for previous acute acalculous cholecystitis. There was no

signicant difference in the conversion rate for early and

delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute calculous

cholecystitis (P = 0240) or acute biliary pain (P = 1000).

Reason for conversion

Thirteen of the 15 patients with acute calculous

cholecystitis who required conversion in the early setting

had severe inammation that obscured the plane of

dissection and anatomy around Calots triangle; conversion

was necessary in the other two patients because of bile duct

stones (one patient) and uncontrolled bleeding (one). In

the elective setting all seven conversions were required

because dense adhesions were present. As three patients

had undergone previous abdominal surgery, adhesions

discovered during cholecystectomy could not be attributed

solely to previous acute cholecystitis.

Among patients with acute biliary pain, three conver-

sions were required in the early setting because of obscure

anatomy with injury to a grossly dilated common hepatic

duct (one patient), adhesions (one) and common bile duct

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Early management of gallbladder disease 589

stone (one). In elective surgery, the reasons were common

bile duct stone in one patient and adhesions in two patients

who had undergone previous abdominal surgery.

Conversion was necessary in one patient with acute

acalculous cholecystitis because of severe inammation.

Timing of laparoscopic surgery

For acute gallstone cholecystitis, the conversion rate

was signicantly higher when surgery was carried out

more than 48 h after admission or later as an elective

procedure. Of the 26 patients undergoing laparoscopic

cholecystectomy within 48 h of admission, one required

conversion (owing to a bile duct stone), compared with

14 of the 52 patients having early surgery after 48 h and

seven of the 21 operated on electively at a later date

(P = 0014) (Table 4). When only conversions required for

inammation or adhesions were considered and patients

who had undergone abdominal surgery previously were

excluded, the conversion rates were none of 25, 13 of 51

and four of 18 respectively (P = 0005) (Table 4).

There was no signicant difference in the conversion

rate between patients with acute cholecystitis operated on

within 48 h of admission (one of 26) and those with acute

biliary pain who had surgery in either the acute (three of

85) or the elective (three of 65) setting (P = 1000). There

was no signicant difference in the mean age (40 versus

51 versus 59 years; P = 0117) or male : female sex ratio

(17 : 9 versus 31 : 21 versus 12 : 9; P = 0890) of patients

undergoing surgery within 48 h, after 48 h, or later as an

elective patient (Table 4).

Complications and hospital stay

Operations for acute calculous cholecystitis carried out

within 48 h of admission were associated with a lower

overall rate of complications than surgery undertaken after

48 h (11 of 52) or (six of 21) (Table 4). There was a higher

rate of postoperative bile leakage in early operations after

Table 4 Comparison of patients with acute calculous cholecystitis who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy before and after 48 h of

admission, and those who had elective surgery

Timing of surgery

Early (n = 78)

<48 h

(n = 26)

>48 h

(n = 52)

Elective

(n = 21) P

LC requiring conversion 1 14 7 0014

LC requiring conversion owing to inammation or adhesions 0 of 25 13 of 51 4 of 18 0005

Histological ndings

Acute inammation 16 42 2

Empyema 1 4 1

Gangrene 9 5 0

Perforation 0 1 1

Chronic inammation 0 0 17

Consultant : trainees ratio

Attempted LCs 3 : 23 6: 46 6: 15 >0100

Converted LCs 0 : 01 0: 14 2: 05 1000

Median (range) hospital stay (nights) 3 (112) 6 (320) 7 (315)* <0001

Total no. of complications 3 11 6

Intraoperative

Bleeding 0 1 0

Gallbladder puncture (bile or stone spillage) 0 3 2

Small tear at falciform ligament 0 0 1

Postoperative

Cardiac event 1 1 0

Hypoxia 2 0 0

Pulmonary embolism 0 0 1

Bile leak 0 4 1 0400

Ileus 0 1 0

Urinary retention 0 1 0

Diarrhoea 0 0 1

*Includes both acute and elective admissions. LC, laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Excluding patients who had undergone abdominal surgery previously.

Fishers exact (two-tailed) test; Kruskal Wallis test.

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

590 W. K. Peng, Z. Sheikh, S. J. Nixon and S. Paterson-Brown

48 h than for surgery within 48 h or elective operations,

but the difference was not signicant (P = 0400) (Table 4).

Total hospital stay was signicantly shorter for patients

with acute calculous cholecystitis when the operation was

carried out within 48 h than for those who had surgery

after 48 h or elective operation (P < 0001) (Table 4).

Outcome of surgery by trainees and consultants

Eighty-four (85 per cent) of the 99 laparoscopic procedures

for acute calculous cholecystitis (in both acute and elective

settings) were performed by trainees (supervised and

unsupervised), but no signicant difference in conversion

rate was found between trainees and consultants in either

setting (Table 4). Neither was there a signicant difference

in the conversion rate of laparoscopic operations (early or

delayed) for acute biliary pain carried out by trainees (three

of 118; 25 per cent) or consultants (three of 32; 9 per cent)

(P = 0112).

Discussion

This study has conrmed and further claried the

results of other reports

3,5,6,10,11

showing the benets

of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy in patients with

acute calculous gallbladder disease. There is now good

evidence to support early operative management

1,36,10,11

in patients t for surgery, which should be carried out

laparoscopically within 48 h of admission, where possible.

If the patient is unable to undergo surgery within 48 h,

it is still worth proceeding with the operation within the

same acute setting as, owing to the formation of dense

inammatory adhesions, the conversion rate is similar to

that for patients returning at a later date for an elective

procedure. The higher complication rate in patients

undergoing delayed surgery either more than 48 h after

admission or subsequently as an elective procedure also

supports a policy of early surgery. Furthermore, early

operation in these patients may avoid the subsequent

need for readmission and emergency surgery following

discharge, which occurred in 21 per cent of patients in the

present study.

There is good evidence from randomized trials

in support of early laparoscopic cholecystectomy

3,5

.

However, the ideal interval from admission to early

surgery has yet to be agreed universally. Differences

in the conclusions of various studies may be explained

by methodological variations, such as the time interval

being from onset of symptoms to surgery or from time

of admission to surgery. In addition, some studies have

combined data from patients with acute cholecystitis and

those with simple acute biliary pain but no inammation.

Most studies have reported an optimal delay to surgery of

between 72 and 96 h

79,1215

, but some found no effect of

a prolonged delay on conversion rate

16,17

. Consistent with

the present results, an optimal maximum delay of 48 h was

proposed in two other studies

7,18

.

This study has demonstrated a difference in the

early operative intervention rate between patients with

inammatory cholecystitis (627 per cent) and those with

pain but no inammation (358 per cent). There was a clear

tendency to defer surgery in older patients in both groups,

but this does not explain the differing rates of operation

as patients with pain but no inammation were generally

younger. There were no other apparent differences in case

mix between these two groups, although a prospective

quantitative risk assessment was not undertaken. A

dedicated 24-h emergency operating theatre was available

throughout this study, but demand on its use meant that

it was not always available during the standard working

day; as a result, many patients with simple biliary pain

whose symptoms settled quickly were discharged, to return

for elective surgery at a later date. Interestingly, deferred

surgery in patients with no inammation was not associated

with an increased conversion rate, whereas deferment

of inamed cases appeared to increase the subsequent

technical difculty rather than reduce it. Thus the widely

held concept of delaying surgery to allow inammation to

settle and ease subsequent surgery appears to be awed.

During this study, patients were managed by a general

on-call team that included some consultants whose elective

practice did not encompass laparoscopic cholecystectomy;

this undoubtedly inuenced the practice of early or

delayed cholecystectomy. In August 2002, Edinburgh

developed a specialist on-call service for both upper and

lower gastrointestinal emergencies, and the results of

an early audit have demonstrated a much higher early

cholecystectomy rate. Similar results have also been shown

by surgeons in Portsmouth, UK

19

.

There is, of course, a group of patients with calculous

or acalculous cholecystitis who are not t for early

cholecystectomy, in whom management often poses a

challenge to the surgeons. Recent reports have suggested

that these high-risk patients, who are often ill from other

conditions, should be managed by cholecystostomy in

the rst instance

20

; they may not require subsequent

cholecystectomy at all, particularly those without stones

21

.

This is certainly becoming the authors policy, except

where the patients clinical conditionimproves rapidly after

the initial non-operative management and conrmation of

diagnosis.

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Early management of gallbladder disease 591

The present study has identied clear differences in

outcome of early and delayed surgery for acute calculous

cholecystitis and acute biliary pain. Patients with acute

biliary pain obviously benet from early surgery to avoid

recurrent admission, although laparoscopic operations in

the acute and elective setting were associated with a similar

conversion rate. Local resources, and perhaps patient and

surgeon preferences, will dictate which route is taken.

Where separate emergency and elective surgical teams

are available, as is becoming increasingly common in the

UK

22

, early surgery undoubtedly provides efcient use of

resources and helps to minimize waiting lists.

Finally, although there was no difference in conversion

rates between consultants and trainees, the majority of

operations performed by trainees were closely supervised

by consultants and the results should be interpreted

accordingly.

References

1 van der Linden W, Sunzel H. Early versus delayed operation

for acute cholecystitis. A controlled clinical trial. Am J Surg

1970; 120: 713.

2 McArthur P, Cuschieri A, Sells RA, Shields R. Controlled

clinical trial comparing early with interval cholecystectomy

for acute cholecystitis. Br J Surg 1975; 62: 850852.

3 Wilson RG, Macintyre IM, Nixon SJ, Saunders JH,

Varma JS, King PM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy as a safe

and effective treatment for severe acute cholecystitis. BMJ

1992; 305: 394396.

4 Lo CM, Liu CL, Lai EC, Fan ST, Wong J. Early versus

delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for treatment of acute

cholecystitis. Ann Surg 1996; 223: 3742.

5 Lo CM, Liu CL, Fan ST, Lai EC, Wong J. Prospective

randomized study of early versus delayed laparoscopic

cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Ann Surg 1998; 227:

461467.

6 Lai PB, Kwong KH, Leung KL, Kwok SP, Chan AC,

Chung SC et al. Randomized trial of early versus delayed

laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Br J

Surg 1998; 85: 764767.

7 Madan AK, Aliabadi-Wahle S, Tesi D, Flint LM,

Steinberg SM. How early is early laparoscopic treatment of

acute cholecystitis? Am J Surg 2002; 183: 232236.

8 Koo KP, Thirlby RC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in

acute cholecystitis. What is the optimal timing for operation?

Arch Surg 1996; 131: 540545.

9 Rattner DW, Ferguson C, Warshaw AL. Factors associated

with successful laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute

cholecystitis. Ann Surg 1993; 217: 233236.

10 Papi C, Catarci M, DAmbrosio L, Gili L, Koch M,

Grassi GB et al. Timing of cholecystectomy for acute

calculous cholecystitis: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol

2004; 99: 147155.

11 Cheema S, Brannigan AE, Johnson S, Delaney PV,

Grace PA. Timing of laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute

cholecystitis. Ir J Med Sci 2003; 172: 128131.

12 Eldar S, Sabo E, Nash E, Abrahamson J, Matter I.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis:

prospective trial. World J Surg 1997; 21: 540545.

13 Eldar S, Sabo E, Nash E, Abrahamson J, Matter I.

Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy in acute

cholecystitis. Surg Laparosc Endosc 1997; 7: 407414.

14 Pessaux P, Tuech JJ, Rouge C, Duplessis R, Cervi C,

Arnaud JP. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in acute

cholecystitis. A prospective comparative study in patients

with acute vs. chronic cholecystitis. Surg Endosc 2000; 14:

358361.

15 Garber SM, Korman J, Cosgrove JM, Cohen JR. Early

laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. Surg

Endosc 1997; 11: 347350.

16 Knight JS, Mercer SJ, Somers SS, Walters AM, Sadek SA,

Toh SK. Timing of urgent laparoscopic cholecystectomy

does not inuence conversion rate. Br J Surg 2004; 91:

601604.

17 Bhattacharya D, Senapati PS, Hurle R, Ammori BJ. Urgent

versus interval laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute

cholecystitis: a comparative study. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat

Surg 2002; 9: 538542.

18 Willsher PC, Sanabria JR, Gallinger S, Rossi L, Strasberg S,

Litwin DE. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute

cholecystitis: a safe procedure. J Gastrointest Surg 1999; 3:

5053.

19 Mercer SJ, Knight JS, Toh SK, Walters AM, Sadek SA,

Somers SS. Implementation of a specialist-led service for the

management of acute gallstone disease. Br J Surg 2004; 91:

504508.

20 Lo LD, Vogelzang RL, Braun MA, Nemcek AA Jr.

Percutaneous cholecystostomy for the diagnosis and

treatment of acute calculous and acalculous cholecystitis.

J Vasc Interv Radiol 1995; 6: 629634.

21 Sugiyama M, Tokuhara M, Atomi Y. Is percutaneous

cholecystostomy the optimal treatment for acute cholecystitis

in the very elderly? World J Surg 1998; 22: 459463.

22 Addison PDR, Getgood A, Paterson-Brown S. Separating

elective and emergency surgical care (the emergency team).

Scott Med J 2001; 46: 4850.

Copyright 2005 British Journal of Surgery Society Ltd www.bjs.co.uk British Journal of Surgery 2005; 92: 586591

Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- 2012 OiteDokument256 Seiten2012 Oiteaddison wood100% (4)

- Acute Kidney InjuryDokument49 SeitenAcute Kidney InjuryfikasywNoch keine Bewertungen

- Restoration of The Worn Dentition. Part 2Dokument7 SeitenRestoration of The Worn Dentition. Part 2Isharajini Prasadika Subhashni GamageNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tuesday 14 January 2020: BiologyDokument24 SeitenTuesday 14 January 2020: Biologysham80% (5)

- Variation in The Use of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy For Acute CholecystitisDokument5 SeitenVariation in The Use of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy For Acute CholecystitisAziz EzoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 MainDokument4 Seiten1 s2.0 S2667008923000253 Mainal malikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Original Article Reasons of Conversion of Laparoscopic To Open Cholecystectomy in A Tertiary Care InstitutionDokument5 SeitenOriginal Article Reasons of Conversion of Laparoscopic To Open Cholecystectomy in A Tertiary Care InstitutionLuis Carlos Moncada TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Journal ReadingDokument8 SeitenJournal ReadingAnonymous Uh2myPxPHNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Reactive Protein An Independent Predictor of Difficult Emergency CholecystectomyDokument10 SeitenC Reactive Protein An Independent Predictor of Difficult Emergency Cholecystectomysarjan kunwarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Outcomes of Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy in Patients With Mild To Moderate Acute Biliary Pancreatitis: A Randomized Prospective StudyDokument36 SeitenOutcomes of Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy in Patients With Mild To Moderate Acute Biliary Pancreatitis: A Randomized Prospective StudyAnonymous Uh2myPxPHNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Cholecystitis: Computed Tomography (CT) Versus Ultrasound (US)Dokument11 SeitenAcute Cholecystitis: Computed Tomography (CT) Versus Ultrasound (US)deahadfinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Acute Cholecystitis in UK Hospitals: Time For A ChangeDokument4 SeitenManagement of Acute Cholecystitis in UK Hospitals: Time For A ChangeRana BishwoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 10Dokument9 SeitenChapter 10Kanishka SamantaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post-Portoenterostomy Triangular Cord Sign Prognostic Value in Biliary Atresia: A Prospective StudyDokument4 SeitenPost-Portoenterostomy Triangular Cord Sign Prognostic Value in Biliary Atresia: A Prospective StudyWisnu Karya SanjayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?Dokument4 SeitenPattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction: Is There A Change in The Underlying Etiology?neildamiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Per-Operative Conversion of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy To Open Surgery: Prospective Study at JSS Teaching Hospital, Karnataka, IndiaDokument5 SeitenPer-Operative Conversion of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy To Open Surgery: Prospective Study at JSS Teaching Hospital, Karnataka, IndiaSupriya PonsinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6870 FTPDokument10 Seiten6870 FTPAkreditasi Sungai AbangNoch keine Bewertungen

- Percutaneous Abscess Drainage in Patients With Perforated Acute Appendicitis: Effectiveness, Safety, and Prediction of OutcomeDokument8 SeitenPercutaneous Abscess Drainage in Patients With Perforated Acute Appendicitis: Effectiveness, Safety, and Prediction of Outcomereza yunusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 3 AppDokument4 SeitenJurnal 3 AppmaulidaangrainiNoch keine Bewertungen

- BLL 2016 06 328Dokument4 SeitenBLL 2016 06 328alifandoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Risk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryDokument31 SeitenRisk of Failure in Pediatric Ventriculoperitoneal Shunts Placed After Abdominal SurgeryWielda VeramitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesiaforemergency Abdominalsurgery: Carol Peden,, Michael J. ScottDokument13 SeitenAnesthesiaforemergency Abdominalsurgery: Carol Peden,, Michael J. ScottJEFFERSON MUÑOZNoch keine Bewertungen

- Surgical Management of Acute CholecystitisDokument17 SeitenSurgical Management of Acute Cholecystitisgrayburn_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- IMU Learning Outcome: Psychomotor SkillsDokument11 SeitenIMU Learning Outcome: Psychomotor SkillsRameshNoch keine Bewertungen

- Spontaneous Passage of Bile Duct Stones: Frequency of Occurrence and Relation To Clinical PresentationDokument4 SeitenSpontaneous Passage of Bile Duct Stones: Frequency of Occurrence and Relation To Clinical PresentationBenny KurniawanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Predictive Factors For Conversion of Laparoscopic CholecystectomyDokument4 SeitenPredictive Factors For Conversion of Laparoscopic CholecystectomyGilang IrwansyahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Diagnosing Acute CholecystitisDokument2 SeitenDiagnosing Acute CholecystitisJorelle NunagNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art07 PDFDokument6 SeitenArt07 PDFadan2010Noch keine Bewertungen

- Choledochal CystDokument5 SeitenCholedochal CystZulia Ahmad BurhaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Operations Patients Hepatic: Clarification of Risk Factors in With CirrhosisDokument7 SeitenOperations Patients Hepatic: Clarification of Risk Factors in With CirrhosisdaviddchandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liver A BSC DrainDokument8 SeitenLiver A BSC DrainAngelica AmesquitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy For Acute !!!!Dokument9 SeitenLaparoscopic Cholecystectomy For Acute !!!!Anca FlorescuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complikasi LaparosDokument5 SeitenComplikasi LaparosVirdo_pedroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction Is There A PDFDokument3 SeitenPattern of Acute Intestinal Obstruction Is There A PDFMaría José Díaz RojasNoch keine Bewertungen

- JurnalDokument9 SeitenJurnalFrans 'cazper' SihombingNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 4Dokument7 SeitenJurnal 4Ega Gumilang SugiartoNoch keine Bewertungen

- RectopexyDokument7 SeitenRectopexyInzamam Ul HaqNoch keine Bewertungen

- Duct Cholecystectomy: Major LaparoscopicDokument10 SeitenDuct Cholecystectomy: Major LaparoscopicShahnawaz AhangarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionDokument7 SeitenPancreatic ®stula After Pancreatic Head ResectionNicolas RuizNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurnal 3Dokument3 SeitenJurnal 3Ega Gumilang SugiartoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Appendicitis After Liver Transplantation Presentation of JournalDokument16 SeitenAppendicitis After Liver Transplantation Presentation of JournalIndah JamtaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Case Report: Cholecystomegaly: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDokument5 SeitenCase Report: Cholecystomegaly: A Case Report and Review of The LiteratureAnti TjahyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rheumatology Journal Club Gut Vasculitis: by DR Nur Hidayati Mohd SharifDokument36 SeitenRheumatology Journal Club Gut Vasculitis: by DR Nur Hidayati Mohd SharifEida MohdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Transanal Endorectal PullthroughDokument8 SeitenTransanal Endorectal PullthroughMuhammad Harmen Reza SiregarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liver Test Patterns in Patients With Acute Calculous Cholecystitis and or CholedocholithiasisDokument8 SeitenLiver Test Patterns in Patients With Acute Calculous Cholecystitis and or Choledocholithiasismari3312Noch keine Bewertungen

- 14 146 v13n6 2014 RiskCarcinogenesisDokument8 Seiten14 146 v13n6 2014 RiskCarcinogenesisDaphne Ongbit JaritoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Post-Cholecystectomy Acute Injury: What Can Go Wrong?Dokument7 SeitenPost-Cholecystectomy Acute Injury: What Can Go Wrong?Ramyasree BadeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colovesical FistulaDokument4 SeitenColovesical FistulaNisaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annals of Medicine and Surgery: Case ReportDokument4 SeitenAnnals of Medicine and Surgery: Case ReportDimas ErlanggaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laproscopic Vagotony PaperDokument4 SeitenLaproscopic Vagotony Paperpeter_mrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy FinaleDokument5 SeitenSafe Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy FinalenipolinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Serosal Appendicitis: Incidence, Causes and Clinical SignificanceDokument3 SeitenSerosal Appendicitis: Incidence, Causes and Clinical SignificancenaufalrosarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDokument6 SeitenLaparoscopic Appendectomy PostoperativeDamal An NasherNoch keine Bewertungen

- Liang 2008Dokument6 SeitenLiang 2008Novi RobiyantiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Loozen 2017Dokument5 SeitenLoozen 2017Dheana IsmaniarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Colecistitis Aguda CirurgiaDokument7 SeitenColecistitis Aguda Cirurgiajoseaugustorojas9414Noch keine Bewertungen

- Laparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Dokument5 SeitenLaparoscopic Appendectomy For Complicated Appendicitis - An Evaluation of Postoperative Factors.Juan Carlos SantamariaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cheema2003 Article TimingOfLaparoscopicCholecysteDokument4 SeitenCheema2003 Article TimingOfLaparoscopicCholecysteBandac AlexandraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Management of Perforated Peptic Ulcer in A District General HospitalDokument5 SeitenManagement of Perforated Peptic Ulcer in A District General HospitalNurul Fitrawati RidwanNoch keine Bewertungen

- 012011SCNA3Dokument14 Seiten012011SCNA3mariafmhNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tube IleostomyDokument5 SeitenTube IleostomyabhishekbmcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acute Intestinal ObstructionDokument9 SeitenAcute Intestinal ObstructionRoxana ElenaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Atlas of Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: High Resolution Image for New Surgical TechniqueVon EverandAtlas of Laparoscopic Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer: High Resolution Image for New Surgical TechniqueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Histological Comparison of Pulpal Inflamation in Primary Teeth With Occlusal or Proximal CariesDokument8 SeitenHistological Comparison of Pulpal Inflamation in Primary Teeth With Occlusal or Proximal CariesGilmer Solis SánchezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders History Pathophysiology Clinical Features and Rome IVDokument20 SeitenFunctional Gastrointestinal Disorders History Pathophysiology Clinical Features and Rome IVwenyinriantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Community Nursing Care PlanDokument6 SeitenCommunity Nursing Care Plantansincos93% (14)

- REAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ)Dokument8 SeitenREAL in Nursing Journal (RNJ)Anonymous 8hlR5KvNoch keine Bewertungen

- Day 1 - GynacologyDokument204 SeitenDay 1 - GynacologyTingting GeNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sars-Cov-2 & Influenza AB & RSV Antigen Combo Test Kit (Self-Testing)Dokument2 SeitenSars-Cov-2 & Influenza AB & RSV Antigen Combo Test Kit (Self-Testing)Ignacio PerezNoch keine Bewertungen

- (S-W5-Sun-Gen.S) (By Dr. Emad) Gall Bladder 1Dokument28 Seiten(S-W5-Sun-Gen.S) (By Dr. Emad) Gall Bladder 1Haider Nadhem AL-rubaiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Digestive WorksheetDokument8 SeitenDigestive WorksheetBrandon KnightNoch keine Bewertungen

- Psychological Complication in PuerperiumDokument17 SeitenPsychological Complication in Puerperiumbaby100% (2)

- Cost Per Test PC400 2020Dokument10 SeitenCost Per Test PC400 2020fischaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Funda DemoDokument10 SeitenFunda DemoariadnebabasaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Media Release - COVID-19Dokument2 SeitenMedia Release - COVID-19Executive Director100% (2)

- Grand Halad Sa Kapamilya: List of ServicesDokument2 SeitenGrand Halad Sa Kapamilya: List of ServicesLeo LastimosaNoch keine Bewertungen

- World AIDS Day 2023-21797Dokument3 SeitenWorld AIDS Day 2023-21797shyamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endocrine PancreasDokument21 SeitenEndocrine Pancreaslacafey741Noch keine Bewertungen

- Upper GI Drugs (Pod Pharm 2023, Thatcher)Dokument39 SeitenUpper GI Drugs (Pod Pharm 2023, Thatcher)8jm6dhjdcpNoch keine Bewertungen

- Therapeutic Plasma Exchange in Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic PurpuraDokument9 SeitenTherapeutic Plasma Exchange in Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpurasugi9namliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trauma in Early Childhood: A Neglected PopulationDokument20 SeitenTrauma in Early Childhood: A Neglected PopulationFrancisca AldunateNoch keine Bewertungen

- ADR Notes KINJAL S. GAMITDokument13 SeitenADR Notes KINJAL S. GAMITKinjal GamitNoch keine Bewertungen

- 33rd IACDE National Conference 2018 - VijayawadaDokument5 Seiten33rd IACDE National Conference 2018 - VijayawadaHari PriyaNoch keine Bewertungen

- CBCT-Scan in DentistryDokument24 SeitenCBCT-Scan in DentistryBilly Sam80% (5)

- 8 Cns StimulantsDokument46 Seiten8 Cns StimulantslouradelNoch keine Bewertungen

- First Aid For The Usmle Step 1 2022-Mcgraw-Hill Education 2022Dokument1 SeiteFirst Aid For The Usmle Step 1 2022-Mcgraw-Hill Education 2022Beto RendonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ebook John Murtaghs General Practice Companion Handbook PDF Full Chapter PDFDokument67 SeitenEbook John Murtaghs General Practice Companion Handbook PDF Full Chapter PDFroberto.duncan209100% (27)

- What? Who?: DR - Mabel Sihombing Sppd-Kgeh DR - Ilhamd SPPD Dpertemen Ilmu Penyakit Dalam Rs - Ham/Fk-Usu MedanDokument45 SeitenWhat? Who?: DR - Mabel Sihombing Sppd-Kgeh DR - Ilhamd SPPD Dpertemen Ilmu Penyakit Dalam Rs - Ham/Fk-Usu MedanM Rizky Assilmy LubisNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lesson Plan On Nursing Care of A Patient With Acute Renal FailureDokument17 SeitenLesson Plan On Nursing Care of A Patient With Acute Renal FailurePriyanka NilewarNoch keine Bewertungen