Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Luck and Moral Responsibility in Free Will Debates

Hochgeladen von

AvantikaBhowmickOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Luck and Moral Responsibility in Free Will Debates

Hochgeladen von

AvantikaBhowmickCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Home > Freedom > Luck

Luck

Luck is an essential part of any discussion of moral responsibility. Some critics have tried to mistakenly make it an

objection to libertarian free will.

Since the world contains irreducible chance, many unintended consequences of our actions are out of our control.

Nevertheless, we are often held responsible for actions that were intended as good, but that had bad consequences.

Similarly, we occasionally are praised for actions that were either neutral or possibly blameworthy, but which had

good consequences.

In a deterministic world, it is hard to see how we can be held responsible for any of our actions.

Counterintuitively, semicompatibilist philosophers hold that whether determinism or indeterminism is true, we can still

have moral responsibility.

At the other end of the spectrum, some libertarians are critical of any free will model that involves chance, because the

apparent randomness of outcomes would make such free will unintelligible. They say it would be a matter of luck.

This is the Luck Objection to free will.

Unfortunately, much of what happens in the real world contains a good deal of luck. Luck gives rise to many of the

moral dilemmas that lead to moral skepticism.

Whether determinist, compatibilist, semicompatibilist, or libertarian, it seems unreasonable to hold persons responsible

for the unintended consequences of their actions, good or bad. In many moral and legal systems, it the person's

intentions that matter first and foremost.

And in any case, actions need not have moral consequences to be free, that would commit the ethical fallacy.

Free will is a prerequisite for responsibility. Whether a free action involves moral responsibility is a question for the

ethicists.

To be responsible for our actions, they must have been caused by something within us, they must "depend on us" (the

Greeks called this ). Modern "agent-causal" theorists demand that something in the agent's mind - perhaps a

uniquely mental substance - gives us the power to cause our actions.

In our Cogito model, responsibility comes from an adequately determined will choosing from among randomly

generated alternative possibilities.

But to the extent that the alternative possibilities included randomly generated ones that allowed us to do good things,

can we properly take credit for them if luck played a role in their generation?

And when we admit some indeterminism into our decision, by flipping a mental coin, can we take responsibility for

whichever choice we have made at random?

Four modern philosophers have grappled with the problem of "Moral Luck." They include Thomas Nagel, Bernard

Williams, and Alfred Mele, and Nicholas Rescher.

The Luck Objection

Luck is only a problem for moral responsibility. Some critics have mistakenly made it an objection to libertarian free

will.

Since the world contains irreducible chance, many unintended consequences of our actions are out of our control.

Unfortunately, much of what happens in the real world contains a good deal of luck. Luck gives rise to many of the

moral dilemmas that lead to moral skepticism.

Whether determinist, compatibilist, semicompatibilist, or libertarian, it seems unreasonable to hold persons responsible

for the unintended consequences of their actions, good or bad. In many moral and legal systems, it the person's

intentions that matter first and foremost.

Nevertheless, we are often held responsible for actions that were intended as good, but that had bad consequences.

Similarly, we occasionally are praised for actions that were either neutral or possibly blameworthy, but which had

good consequences.

Some thinkers are critical of any free will model that involves chance, because the apparent randomness of decisions

would make such free will unintelligible. They say our actions would be a matter of luck. This is the Luck Objection to

free will.

Thomas Nagel on Moral Luck

In his 1979 essay "Moral Luck," Nagel is pessimistic about finding morally responsible agents in a world that views

agents externally, reducing them to happenings, to sequences of events, following natural laws, whether deterministic

or indeterministic. Free will and moral responsibility seem to be mere illusions.

Moral judgment of a person is judgment not of what happens to him, but of him. It does not say merely that a certain

event or state of affairs is fortunate or unfortunate or even terrible. It is not an evaluation of a state of the world, or of

an individual as part of the world. We are not thinking just that it would be better if he were different, or did not exist,

or had not done some of the things he has done. We are judging him, rather than his existence or characteristics. The

effect of concentrating on the influence of what is not under his control is to make this responsible self seem to

disappear, swallowed up by the order of mere events.

What, however, do we have in mind that a person, must be to be the object of these moral attitudes? While the concept

of agency is easily undermined, it is very difficult to give it a positive characterization. That is familiar from the

literature on Free Will.

We cannot simply take an external evaluative view of ourselves - of what we most essentially are and what we do. And

this remains true even when we have seen that we are not responsible for our own existence, or our nature, or the

choices we have to make, or the circumstances that give our acts the consequences they have. Those acts remain ours

and we remain ourselves, despite the persuasiveness of the reasons that seem to argue us out of existence.

It is this internal view that we extend to others in moral judgment - when we judge them rather than their desirability or

utility. We extend to others the refusal to limit ourselves to external evaluation, and we accord to them selves like our

own. But in both cases this comes up against the brutal inclusion of humans and everything about them in a world from

which they cannot be separated and of which they are nothing but contents. The external view forces itself on us at the

same time that we resist it. One way this occurs is through the gradual erosion of what we do by the subtraction of

what happens.

The inclusion of consequences in the conception of what we have done is an acknowledgment that we are parts of the

world, but the paradoxical character of moral luck which emerges from this acknowledgment shows that we are unable

to operate with such a view, for it leaves us with no one to be.

Nagel presents the standard two-part argument against free will

The same thing is revealed in the appearance that determinism obliterates responsibility. Once we see an aspect of

what we or someone else does as something that happens, we lose our grip on the idea that it has been done and that

we can judge the doer and not just the happening. This explains why the absence of determinism is no more hospitable

to the concept of agency than is its presence a point that has been noticed often. Either way the act is viewed

externally, as part of the course of events.

The problem of moral luck cannot be understood without an account of the internal conception of agency and its

special connection with the moral attitudes as opposed to other types of value. I do not have such an account. The

degree to which the problem has a solution can be determined only by seeing whether in some degree the

incompatibility between this conception and the various ways in which we do not control what we do is only apparent.

I have nothing to offer on that topic either. But it is not enough to say merely that our basic moral attitudes toward

ourselves and others are determined by what is actual; for they are also threatened by the sources of that actuality, and

by the external view of action which forces itself on us when we see how everything we do belongs to a world that we

have not created.

(Moral Luck, reprinted in Mortal Questions, Cambridge, 1979, p.37-38)

Bernard Williams on Moral Luck

I entirely agree with [Nagel] that the involvement of morality with luck is not something that can simply be accepted

without calling our moral conceptions into question. That was part of my original point; I have tried to state it more

directly in the present version of this paper. A difference between Nagel and myself is that I am more sceptical about

our moral conceptions than he is.

Scepticism about the freedom of morality from luck cannot leave the concept of morality where it was, any more than

it can remain undisturbed by scepticism about the very closely related image we have of there being a moral order,

within which our actions have a significance which may not be accorded to them by mere social recognition. These

forms of scepticism will leave us with a concept of morality, but one less important, certainly, than ours is usually

taken to be; and that will not be ours, since one thing that is particularly important about ours is how important it is

taken to be.

Alfred Mele on Luck and Free Will

Mele says there is a problem about luck for Libertarians

Agents' control is the yardstick by which the bearing of luck on their freedom and moral responsibility is measured.

When luck (good or bad) is problematic, that is because it seems significantly to impede agents' control over

themselves or to highlight important gaps or shortcomings in such control. It may seem that to the extent that it is

causally open whether or not, for example, an agent intends in accordance with his considered judgment about what it

is best to do, he lacks some control over what he intends, and it may be claimed that a positive deterministic

connection between considered best judgment and intention would be more conducive to freedom and moral

responsibility.

This last claim will be regarded as a nonstarter by anyone who holds that freedom and moral responsibility require

agential control and that determinism is incompatible with such control. Sometimes it is claimed that agents do not

control anything at all if determinism is true. That claim is false.

As soon as any agent...judges it best to A, objective probabilities for the various decisions open to the agent are set,

and the probability of a decision to A is very high. Larger probabilities get a correspondingly larger segment of a tiny

indeterministic neural roulette wheel in the agent's head than do smaller probabilities. A tiny neural ball bounces along

the wheel; its landing in a particular segment is the agent's making the corresponding decision. When the ball lands in

the segment for a decision to A, its doing so is not just a matter of luck. After all, the design is such that the probability

of that happening is very high. But the ball's landing there is partly a matter of luck.

All libertarians who hold that A's being a free action depends on its being the case that, at the time, the agent was able

to do otherwise freely then should tell us what it could possibly be about an agent who freely A-ed at t in virtue of

which it is true that, in another world with the same past and laws of nature, he freely does something else at t. Of

course, they can say that the answer is "free will." But what they need to explain then is how free will, as they

understand it, can be a feature of agents or, more fully, how this can be so where free will, on their account of it,

really does answer the question. To do this, of course, they must provide an account of free will one that can be

tested for adequacy in this connection.

(Free Will and Luck, p.7-9)

Free will is a prerequisite for responsibility. Whether a free action involves moral responsibility is a question for the

ethicists.

But in any case, to the extent that luck is involved in an agent's free actions, that is a problem for moral responsibility.

Chapter 3.7 - The Ergod Chapter 4.2 - The History of Free Will

Part Three - Value Part Five - Problems

Normal | Teacher | Scholar

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Thomas NagelDokument7 SeitenThomas NagelDavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Act 1 - Module 4 FreedomDokument2 SeitenAct 1 - Module 4 FreedomJustine JaymaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moral Luck: Thomas Nagel Introduces Us To The Role of Chance in Our Moral JudgmentsDokument3 SeitenMoral Luck: Thomas Nagel Introduces Us To The Role of Chance in Our Moral JudgmentsJohn ClementeNoch keine Bewertungen

- NAGEL Moral LuckDokument9 SeitenNAGEL Moral LuckdaniellestfuNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thomas Nagel Moral LuckDokument9 SeitenThomas Nagel Moral Luckkb_biblioNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moral Luck: Foundations of The Metaphysics of Morals, First Section, Third ParagraphDokument10 SeitenMoral Luck: Foundations of The Metaphysics of Morals, First Section, Third ParagraphPEDROSA, Bea NicoleNoch keine Bewertungen

- Class Notes For Philosophy 251Dokument3 SeitenClass Notes For Philosophy 251watah taNoch keine Bewertungen

- Creatures of Possibility: The Theological Basis of Human FreedomVon EverandCreatures of Possibility: The Theological Basis of Human FreedomNoch keine Bewertungen

- Summary of Determined By Robert M. Sapolsky: A Science of Life without Free WillVon EverandSummary of Determined By Robert M. Sapolsky: A Science of Life without Free WillNoch keine Bewertungen

- PH103 2nd Formative PlanDokument8 SeitenPH103 2nd Formative PlanJohn BobNoch keine Bewertungen

- Module in Moral ActsDokument9 SeitenModule in Moral ActsRandy OrtegaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nagel Moral LuckDokument5 SeitenNagel Moral LuckIra DavidNoch keine Bewertungen

- Habit 1: Be Proactive - Principles of Personal VisioDokument2 SeitenHabit 1: Be Proactive - Principles of Personal VisioedrearamirezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moral Responsibility: Philosophy 120Dokument13 SeitenMoral Responsibility: Philosophy 120Judea AlviorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Positive Harmlessness in Practice: Enough for Us All, Volume TwoVon EverandPositive Harmlessness in Practice: Enough for Us All, Volume TwoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Action in the Moment: Self-Awareness and Intuition for Leaders in Ambiguous TimesVon EverandAction in the Moment: Self-Awareness and Intuition for Leaders in Ambiguous TimesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Moral Materialism: A Semantic Theory of Ethical NaturalismVon EverandMoral Materialism: A Semantic Theory of Ethical NaturalismNoch keine Bewertungen

- Becoming a Person of Destiny: Discovering and Fulfilling Your Life's PurposeVon EverandBecoming a Person of Destiny: Discovering and Fulfilling Your Life's PurposeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Problem of MoralsDokument8 SeitenThe Problem of MoralsKyle C MolinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Art of Letting Go: Stop Overthinking, Stop Negative Spirals, and Find Emotional FreedomVon EverandThe Art of Letting Go: Stop Overthinking, Stop Negative Spirals, and Find Emotional FreedomBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- A Contemporary Introduction To Free Will: Download This Free PDF Summary HereDokument10 SeitenA Contemporary Introduction To Free Will: Download This Free PDF Summary Heregk80823Noch keine Bewertungen

- Find Freedom Within You: Mind Psychology You Don't Know AboutVon EverandFind Freedom Within You: Mind Psychology You Don't Know AboutNoch keine Bewertungen

- Hard CompatiblismDokument44 SeitenHard CompatiblismChris WalkerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free Will Issue IntroducedDokument2 SeitenFree Will Issue IntroducedLoren ChilesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Livre Arbítrio TempletonDokument67 SeitenLivre Arbítrio TempletonWagner CondorNoch keine Bewertungen

- Is There Such a Thing as Free WillDokument3 SeitenIs There Such a Thing as Free WillJiadong YeNoch keine Bewertungen

- 1ys EssayDokument9 Seiten1ys Essayapi-654886415Noch keine Bewertungen

- Conscience & Fanaticism: An Essay on Moral ValuesVon EverandConscience & Fanaticism: An Essay on Moral ValuesNoch keine Bewertungen

- 6 Moral FailureDokument20 Seiten6 Moral FailuresantichopraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Human Nature And Conduct - An Introduction To Social PsychologyVon EverandHuman Nature And Conduct - An Introduction To Social PsychologyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lec 4.5 Freedom and Hierarchy of Values Copy-2Dokument45 SeitenLec 4.5 Freedom and Hierarchy of Values Copy-2Juliana Rei ChavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Voluntariness and Moral ResponsibilityDokument63 SeitenVoluntariness and Moral Responsibilitymaria hardenNoch keine Bewertungen

- Reflection Paper - 2Dokument2 SeitenReflection Paper - 2arslanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Morality - Subjective Vs ObjectiveDokument7 SeitenMorality - Subjective Vs ObjectiveBrian BlackwellNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy Essay 1-Moral Responsibility and Free WillDokument3 SeitenPhilosophy Essay 1-Moral Responsibility and Free WillALDEN STEWART FARRARNoch keine Bewertungen

- EthicsDokument20 SeitenEthicsPatrick WatanabeNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Saving Lie: Truth and Method in the Social SciencesVon EverandThe Saving Lie: Truth and Method in the Social SciencesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Free Will and Determinism EssayDokument2 SeitenFree Will and Determinism EssayFrazer Carr100% (1)

- Do WeTake Revenge on People that Wronged Us or Set Things Right Guide?Von EverandDo WeTake Revenge on People that Wronged Us or Set Things Right Guide?Noch keine Bewertungen

- Three Main Areas of Moral PhilosophyDokument19 SeitenThree Main Areas of Moral PhilosophysaurabhNoch keine Bewertungen

- AggressionDokument54 SeitenAggressionادیبہ اشفاقNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3330602Dokument5 Seiten3330602Patel ChiragNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nicole Mcnelis Resume GenericDokument2 SeitenNicole Mcnelis Resume Genericapi-604614058Noch keine Bewertungen

- Report - Thirty Ninth Canadian Mathematical Olympiad 2007Dokument15 SeitenReport - Thirty Ninth Canadian Mathematical Olympiad 2007Nguyễn Minh HiểnNoch keine Bewertungen

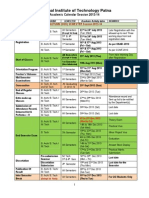

- Nit Patna Academic CalendarDokument3 SeitenNit Patna Academic CalendarAnurag BaidyanathNoch keine Bewertungen

- ASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Dokument18 SeitenASEAN Quality Assurance Framework (AQAF)Ummu SalamahNoch keine Bewertungen

- CAV JanuaryCOADokument58 SeitenCAV JanuaryCOAGina GarciaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jonathon Swift Mini Lesson and HandoutDokument2 SeitenJonathon Swift Mini Lesson and Handoutapi-252721756Noch keine Bewertungen

- VM Foundation scholarship applicationDokument3 SeitenVM Foundation scholarship applicationRenesha AtkinsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Éric Alfred Leslie Satie (FrenchDokument3 SeitenÉric Alfred Leslie Satie (FrenchAidan LeBlancNoch keine Bewertungen

- Note On Leo Strauss' Interpretation of RousseauDokument8 SeitenNote On Leo Strauss' Interpretation of Rousseauhgildin100% (1)

- Application for PhD Supervisor Recognition at SAGE UniversityDokument3 SeitenApplication for PhD Supervisor Recognition at SAGE UniversityPrashant100% (1)

- Quality Culture Ch.6Dokument15 SeitenQuality Culture Ch.6flopez-2Noch keine Bewertungen

- Curriculum Design Considerations (1) M3Dokument13 SeitenCurriculum Design Considerations (1) M3Hanil RaajNoch keine Bewertungen

- IJM Corporation Berhad 2003 Annual Report Highlights Construction Awards, International GrowthDokument172 SeitenIJM Corporation Berhad 2003 Annual Report Highlights Construction Awards, International GrowthDaniel Yung ShengNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intervention Plan in Tle: Name of Learners: Grade and Level: School Year: Quarter/sDokument2 SeitenIntervention Plan in Tle: Name of Learners: Grade and Level: School Year: Quarter/sGilly EloquinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Form 2 Personal Statement - Environmental Landscape ArchitectureDokument2 SeitenForm 2 Personal Statement - Environmental Landscape ArchitectureOniwinde OluwaseunNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vocabulary Development and Comprehension Skills Through Word Games Among Grade 4 LearnersDokument11 SeitenVocabulary Development and Comprehension Skills Through Word Games Among Grade 4 LearnersPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annotaion Obj. 4Dokument9 SeitenAnnotaion Obj. 4Jackie Lou AlcantaraNoch keine Bewertungen

- BCA Course PlanDokument78 SeitenBCA Course Plansebastian cyriacNoch keine Bewertungen

- 311 1168 2 PB PDFDokument6 Seiten311 1168 2 PB PDFFRANSISKA LEUNUPUNNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arkansas Mathematics Curriculum Framework: GeometryDokument23 SeitenArkansas Mathematics Curriculum Framework: GeometryArun YadavNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vicente - Chapter 3Dokument4 SeitenVicente - Chapter 3VethinaVirayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anita Gray Resume, Making A DifferenceDokument3 SeitenAnita Gray Resume, Making A DifferenceyogisolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Aboriginal Education Assignment 2Dokument10 SeitenAboriginal Education Assignment 2bhavneetpruthyNoch keine Bewertungen

- How to Pass the Bar Exams: Tips for Bar Review and ExamsDokument5 SeitenHow to Pass the Bar Exams: Tips for Bar Review and ExamsJoyae ChavezNoch keine Bewertungen

- LM - Dr. Jitesh OzaDokument94 SeitenLM - Dr. Jitesh OzaDakshraj RathodNoch keine Bewertungen

- Unit Test 14Dokument2 SeitenUnit Test 14ana maria csalinasNoch keine Bewertungen

- Multi-Genre Text SetDokument34 SeitenMulti-Genre Text Setapi-312802963100% (1)

- MAPEH PE 9 Activity Sheet Week 4Dokument1 SeiteMAPEH PE 9 Activity Sheet Week 4Dave ClaridadNoch keine Bewertungen