Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Fostering Spirituality in A Preschool Sunday School

Hochgeladen von

elvine0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

103 Ansichten213 SeitenOriginaltitel

Fostering Spirituality in a Preschool Sunday School

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

103 Ansichten213 SeitenFostering Spirituality in A Preschool Sunday School

Hochgeladen von

elvineCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 213

FOSTERING SPIRITUALITY IN A PRESCHOOL SUNDAY SCHOOL

WITH A TEAM OF GRANDFATHERS USING

BLESSING-BASED SPIRITUAL NURTURE

Cara E. Koch

Bachelor of Science Degree, South Dakota State University, 1966

Master of Science Degree, Wheelock College, 1990

Mentors

Donald B. Rogers, Ph.D.

Reverend Leanne Ciampa Hadley, M.Div.

Elder J acqueline Nowak, MARE, CCE

A FINAL PROJ ECT SUBMITTED TO

THE DOCTORAL STUDIES COMMITTEE

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS

FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF MINISTRY

UNITED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

TROTWOOD, OHIO

DECEMBER, 2007

United Theological Seminary

Dayton, Ohio

Faculty Approval Page

Doctor of Ministry Final Project Dissertation

FOSTERING SPIRITUALITY IN A PRESCHOOL SUNDAY SCHOOL

WITH A TEAM OF GRANDFATHERS USING

BLESSING-BASED SPIRITUAL NURTURE

by

Cara E. Koch

United Theological Seminary, 2007

Mentors

Donald B. Rogers, Ph.D.

Reverend Leanne Ciampa Hadley, M.Div.

Elder J acqueline Nowak, MARE, CCE

Date: _________________________

Approved:

___________________________________

___________________________________

Mentor(s):

__________________________

Director, Doctoral Studies

Copyright2007 Cara E. Koch

All rights reserved.

iii

Table of Contents

ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................... vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS...............................................................................................viii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.......................................................................................... viix

LIST OF TABLES...............................................................................................................x

INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................1

CHAPTER

1. MINISTRY FOCUS...............................................................................................3

The Grandpa Program

2. THE STATE OF THE ART IN UNDERSTANDING CHILDRENS

S SPIRITUALITY ..................................................................................................12

Overview

Biblical Foundation

Historical

Theological

Spiritual Practitioners

Child Development, Psychology, Education and Brain Research

Research on Childrens Spirituality

3. THEORETICAL FOUNDATION AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE..............23

Biblical Foundation

Theological Foundation

Saint Augustine

Meister Eckhart

iv

Comenius

J ohn Wesley

Horace Bushnell

Karl Rahner

Toward a Theology of Childhood

Historical Foundation

The History of Children

Ancient Greco-Roman Culture

Ancient J ewish Culture

Early Christianity

Middle Ages

The Reformation

The Enlightenment and Modernity

The Spirituality of Children: Related Disciplines

Maria Montessori

The Nature of Childrens Spirituality

Setting Up the Environment

The Role of the Adult

Montessori Materials

Program Structure

Summary

Sophia Cavalletti

The Parable of the Good Shepherd

The Eucharist

Baptism and the Light of Christ

v

J erome Berrymans Godly Play

Teaching With the Physical Space/Environment

Teaching with Time

Teaching with People

Play and Reality

J ames W. Fowler

Infancy and Undifferentiated Faith

Stage 1: Intuitive-Projective Faith

Stage 2: Mythic-Literal Faith

David Hay and Rebecca Nye

4. METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................120

5. FIELD EXPERIENCE................................................................................................123

Pre-Assessment

Welcome/Tea Party

Ritual and Prayer

Scripture

Discovery Boxes

Parent Observations Outside Classroom

Researcher Observations within Classroom

Triangulation with Previous Researchers

6. REFLECTION, SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION.................................................140

Initial Reflections

Summary

Parent Observations outside the Classroom

Researchers Observations within the Classroom

vi

Triangulation Using Previous Research

Suggested Changes

Conclusion

APPENDIX

A. AUTHORIZATIONS...........................................................................................158

B. PROMOTIONAL MATERIALS.........................................................................161

C. INTERVIEW AND SURVEY FORM.................................................................164

D. PARENT COMMUNICATION MATERIALS..................................................167

E TABLES................................................................................................................172

F. FIGURES..............................................................................................................179

BIBLIOGRAPHY............................................................................................................198

Books

Periodicals

Online Sources

vii

ABSTRACT

FOSTERING SPIRITUALITY IN A PRESCHOOL SUNDAY SCHOOL

WITH A TEAM OF GRANDFATHERS USING

BLESING BASED SPIRITUAL NURTURE

by

Cara E. Koch

United Theological Seminary, 2007

Mentors

Donald B. Rogers, Ph.D.

Reverend Leanne Ciampa Hadley, M.Div.

J acqueline Nowak, MARE, CCE

This intergenerational program explored the fostering of spirituality in preschool children

with a team of Grandpas in Sunday school class at First Congregational Church,

Colorado Springs, Colorado, using the principles of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture.

Spirituality was defined as relational consciousness encompassing four categories:

child/self, child/people, child/world and child/God. Five videotaped sessions documented

evidence of the categories of relational consciousness. The evidence of increased

spirituality was triangulated with pre/post parent input, researcher observations, and

previous research. This project challenged the notion that Christian Education is

dependent upon cognitive development, and therefore should not begin until age twelve.

viii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to acknowledge my husband, Harry Wrede, for his never-ending support; my

brother, Ron Koch, for his moral support and help with editing, and my son, Robert

Belton, and my parents, J im and Lucille Koch, for being my teachers on a spiritual

journey that resulted in this document.

ix

ILLUSTRATIONS

Figures Page

1. Godly Play Classroom................................................................................................180

2. Stephanias Altar as Meadow.....................................................................................181

3. Marios Sheep and People Around the Altar..............................................................182

4. The Sheepfold of the Good Shepherd and the Eucharistic Table...............................183

5. Altar with Candle Below; Church and Sheepfold on Either Side...............................184

6. Children with Grandpa at the Tea Party.....................................................................185

7. Pouring J uice with Grandpa........................................................................................186

8. Worship Around the Altar ..........................................................................................187

9. Sharing Prayer with Grandpa......................................................................................188

10. Receiving the Blessing..............................................................................................189

11. Listening to the Parable............................................................................................190

12. Using Quilts to Define Space for Sitting..................................................................191

13. Choosing a Discovery Box.......................................................................................192

14. Sheep Puppets in the discovery Box.........................................................................193

15. The Electric Circuit Discovery Box..........................................................................194

16. The Dress-up Box.....................................................................................................195

17. Being Present............................................................................................................196

18. Building Relationships..............................................................................................197

x

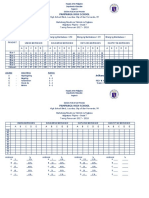

TABLES

Tables Page

1. Godly Play Time Format............................................................................................173

2. Stages of Human Development..................................................................................174

3. Shared Center of Value and Power.............................................................................175

4. Pattern of Worship......................................................................................................176

5. Parents: Relational Consciousness Quotients.............................................................177

6. Researcher: Relational Consciousness Quotients.......................................................178

1

INTRODUCTION

Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture is an approach for providing pastoral care to

hurting children and teens. Developed by Reverend Leanne Hadley of First Steps

Spirituality Center, Colorado Springs, CO, it provides spiritual support to children and

teens who are experiencing crisis in their lives. The method and tools developed by

Reverend Hadley facilitate healing and provide the recipients of her care with inner

resources with which to meet lifes challenges for the rest of their lives.

The Grandpa Program was conceived as a way of exploring the possibility of

using the same principles of fostering spiritual strength with young children who were

not in crisis, in order that they might be helped to develop the inner resources with which

to face the challenges of life when they arise in the future.

The first chapter of this paper describes the experience and observations of the

author that led to the creation of The Grandpa Program as an act of ministry, together

with an explanation of why the context of Sunday school at the First Congregational

Church was chosen. The scope of the research is defined in the second chapter, through

an overview of literary sources for the foundational under girding of this act of ministry,

including literature from Biblical, historical and theological resources, supplemented by

literature from the fields of child development, education, psychology, psychiatry and

neurology. The third chapter presents information gleaned from the literature that was

outlined in chapter two. The research methodology and design are outlined in the fourth

2

chapter. The fifth chapter provides a detailed description of the field experience in the

classroom, followed by an analysis of the data gathered. The sixth and final chapter

reflects upon the data and what insights it reveals, summarizes the findings, and draws

conclusions based upon the information discovered. Finally, the author suggests a

direction for further study in the future.

3

CHAPTER ONE

MINISTRY FOCUS

Having experienced a childhood where spirituality was not a focus, followed later

by a time of serious spiritual seeking as an adult, the author is coming to a personal

spiritual understanding that continues to evolve. Following a career in the field of child

development and family relationships and many years spent working with parents and

their children, the author came to recognize the need for a more informed and

comprehensive understanding of children by church leaders while volunteering in Sunday

school. She recognized as well the need for a better understanding of childrens

spirituality by those who work with children in the secular world.

One of the issues that initially drew her attention to the need for a better

understanding of early childhood development by church leaders is the question of how

to present the Bible stories of the Christian tradition to very young children in a way that

does not make them fearful. As she prepared the lesson for Noahs Arkone of the first

stories in the curriculum introduced to three year olds in Sunday schoolshe realized

how uncomfortable she was in telling a story where God punishes people with drowning

for being bad. She chose to change the story, leaving out the punishment part, and

stressed Gods protection of the animals and Noah. The following year a similar level of

discomfort arose as she observed another teacher using a similar curriculum the first

Sunday after hurricane Katrina. The children had been witnessing on television the

4

drowning of many innocent people. After expressing to the author her concern about

using this story in light of the current happenings, the teacher, a veteran kindergarten

teacher who had taught Sunday school for twenty-five years, introduced the story:

What do you do that is bad? she began.

Get in a fight, was the first answer.

Yes, it is bad to fight, she replied. Some people are just all bad. . . and that

was all that was heard before the author left the room.

What could the children have learned that day? Do they think God might drown

them for fighting with their brother or sister, for example? Or will he drown their parents

for fighting or arguing with each other? Do they believe God drowned the people of

New Orleans because they were bad people? It would not be surprising if some of these

children would not want to come back to Sunday school again.

As a parent and also a long-time professional in the field of child development

and family relationships, the author recognized child rearing to be a daunting spiritual

task, yet this is rarely acknowledged as such in our present day societyat least

outwardly.

Sandy Sasso, a Rabbi and expert on the spirituality of children, recognizes the

challenge of parenting and the spiritual formation of children. As she points out, when

children as young as preschoolers begin to ask existential questions, such as, Where did

we come from? Where do people go when they die? Where does God live? and

Why do people hurt each other? these questions can seem overwhelming to adults who

are still trying to answer these questions for themselves. All children have these types of

questions, andwhether or not they articulate themthey are part of a childs innate

5

spirituality. Our attempt to answer these unanswerable questions is the essence of our

religion, ethics and morality.

1

Today, when so often families are not closely connected to the spiritual traditions

that provided guidance to their fore fathers and mothers; when they are exposed to so

many different traditions in our increasingly diverse society, and when new questions of

ethics and morality arise in an ever-changing world; it seems more critical than ever to be

able to foster spiritual strength in our children. If parents and spiritual leaders are to

support our childrens natural spirituality, it behooves us to find meaningful ways of

responding to these questions.

These observations have stirred this authors search to find a better way for

communities of faith to recognize and support the innate spirituality of young children by

utilizing the most formative years of early childhood to introduce children to the spiritual

language and practices of the Christian tradition. The Grandpa Program, utilizing the

principles of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture, is intended to offer such an alternative.

The context for The Grandpa Program was the First Congregational Church of

Colorado Springs, CO. With a growing membership of approximately 700 members in

2005, the average rate of participation of children and youth had been declining in the

previous two years. Approximately 27% of the families who were members of the church

had children living at home. With 81% of the membership being business or professional

people; a considerable number of the members on the faculty of Colorado College, and

1

Rabbi Sandy Sasso, Speaking of Faith Newsletter, American Public Media, J une 15, 2006,

http://speakingoffaith.publicradio.org/programs/spiritualityofparenting/kristasjournal.html/ (accessed

6/23/2006).

6

thirty-four members who were ordained clergy, there was a distinct intellectual bent in

the culture of the church. This context seemed an ideal one in which to find support for

an innovative approach for working with young children, and one in which the program

would contribute to the stated goal of the church to increase participation of children and

youth. The founding of this program also provided the author with an opportunity to

pursue her own spiritual growth as she continued her lifelong interest in a holistic

approach to childrens growth and development. She was able to find a renewed personal

sense of purpose and generativity as she facilitated a meaningful contribution by the older

men in the congregation to the next generation of children.

The Act of Ministry for this research project was The Grandpa Program. It was

designed to utilize the principles of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture in an investigation

of the spiritual nature of three and four year old children in order to determine whether or

not it might be possible to foster spirituality in children of this age. It was also felt that

close observation of children in a spiritual setting will either support or refute the

investigators intuitive notion that children are innately spiritual. The term spirituality

was defined using specified dimensions of spirituality that had been established by

previous researchers.

The most basic belief of this Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture approach is the

premise that all children are born with innate spirituality: they have a natural sense of

God. It is believed by the practitioners of these principles that when this existing spiritual

sense is strengthened and reinforced, it can be a source of profound inner strength, even

in very young children. It is also believed that this spiritual sense can continue to grow

throughout a lifetime, available to be tapped into whenever it is needed.

7

Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture originated with the work of Reverend Leanne

Hadley, Elder in the United Methodist Church, as she provided spiritual care to children

and teens who were experiencing hurt or pain in their lives. As she listened to those

children and teens who sought her care, and as she reflected on their words and actions,

she identified some basic principles which she found to be helpful in the healing process.

She did not provide therapy, or attempt to fix them. Rather, as she journeyed with and

listened to participants, she focusing on the core goodness in each child or teen, and was

totally present to whatever was being shared.

Through this process Reverend Hadley has identified some key elements that are

central to this type of spiritual nurture. The first of these she called Holy Listening,

described by Rev. Hadley as a simple yet profound method of honoring the spirit of

another through listening without judging, criticizing or evaluating, and allowing God to

be a third party in the conversation. In this process of listening without imposition or

any effort to change the child, a feeling of connection to the wholeness of God occurs, on

the part of both the listener and the child.

Holy Listening is facilitated when it is practiced within Holy Spacethe second

key element of spiritual nurture. Simply put, Holy Space is a space where God is heard.

In order to help children learn to hear God, a calm and peaceful atmosphere with an easy

sense of order is essential. Furniture needs to be appropriate to the size of child, with art

and other materials easily accessible. A general routine for what happens in Holy Space

is important also, as it provides a sense of security and safety within which to allow

feelings to surface. When children achieve such a sensewhen they gain mastery of

their space, they are more easily open to listening to God. Once accustomed to this type

8

of Holy Space, children and teens eventually learn to create an inner space so they can

hear God wherever they may be.

Recognition of the value of silence is a third element of this approach. It provides

an opportunity for reflection on whatever is being experienced, so the child or teen can

contemplate meaning as they ponder what they have just heard or experienced. This

ability to use silence is the beginning of prayer in young children.

A fourth element in the practice of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture is the use of

prayer tools and rituals that have been developed in order to facilitate the process of

connecting with God. Prayer beads, prayer shawls, candles, and Holy Listening Stones

2

are examples of such tools. It is through these tools that children and teens are introduced

to the language and symbols of the J udeo-Christian tradition.

It was the belief of the author that the principles of Blessing Based Spiritual

Nurture which are so effective in healing hurting children and teens, could also be used to

foster the spiritual growth of very young children who are not in a state of crisis, in order

that they might develop a strong spiritual core early in life. So equipped, it is

hypothesized that they should be prepared with inner spiritual strength for dealing with

whatever life has to offer as they face future challenges.

The focus of this research project was to create a Sunday school program for three

and four year olds, utilizing a team of volunteer Grandpas from the congregation, under

the leadership of a facilitator. This program served several purposes:

2

Holy Listening Stones are a set of 25 stones with different symbols which are offered to children

with directions to choose a symbol that shows how they feel.

9

1. To provide three and four year olds with a warm, nurturing first church

experience away from their parents. The theological basis is that childrens early

notion of God is based on their first experiences of safety, security and nurturing.

2. To act in the spirit of, It takes a village to raise a child by relieving parents of

preschoolers from having to volunteer in their own childs group. It is difficult for

parents when children of this age may, as they develop their own autonomy, act

out and test their parents. This new behavior causes some parents to dread the

day they have to volunteer. By delaying parental volunteering until this

developmental stage is over, the initial volunteer experience of parents is more

likely to be a positive one.

3. To match the naturally slower pace of some of the older sources of wisdom in

the church community with young children who need someone to slow down and

listen to them. A relaxed, nurturing environment that facilitates the connection

and bonding of the youngest and oldest of our church community provides a

win/win/win situation for children, parents, and elders.

4. To expose elders in our congregation to the natural spirituality of children, so that

it becomes more widely known and recognized within the congregation that

children are spiritual beings who are capable of developing their spirituality at a

very young age.

10

The Grandpa Program

Within the general focus stated above, the purpose of this ministry was to foster

spiritual growth in both the children and Grandpas through a time of hospitality, prayer

time around an altar, an introduction to Scripture through a presentation of the Good

Shepherd parable, and small group interaction between the children and Grandpas under

the leadership of the researcher. In addition, two new leaders were to be trained, in order

to continue the program after completion of the research.

The format for The Grandpa Program was based upon that of traditional Christian

worship, with four distinct components of fifteen minutes duration each. The Welcome

was a tea party; Ritual and Prayer was conducted around a central altar; Scripture was

presented through a Godly Play presentation of The Parable of the Good Shepherd and a

Response and Closing time consisted of small group interaction between children and

Grandpas as they explored the contents of discovery boxes.

The data for the research was collected by video taping classroom sessions and

audio taping the small group conversations with the Grandpas. In addition, home

interviews with the parents of six children who were designated as research subjects was

conducted prior to the start of the program; a focus group with the Grandpas was

conducted midway in the project, and a follow-up parent questionnaire was completed

following the study.

The Grandpa Program was designed in such a way as to be easily replicable in

other churches as a model for providing a developmentally appropriate spiritual

experience for preschool age children at this most formative period in their young lives.

The use of Grandpas from the congregation helped to expand the relational world of the

11

children beyond that of their immediate family into the wider community of their church

family. The exposure of Grandpas to the spiritual nature of children provided them with

an opportunity to connect with their own spiritual beginning so as to foster their own

spiritual development as they shared their wisdom with the children. The introduction to

Christian language and ritual as the children experienced prayer and the sharing of each

others prayer created a foundation of meaningful spiritual experience quite different

from cognitive learning about religion. The introduction of Godly Play through the

Parable of the Good Shepherd provided children and parents an introduction to this

unique method of discovering Christianity, including its language, and symbolsone that

creates a rich inner spiritual experience. The author felt that church leaders and

volunteers who find themselves excited by this method of fostering spiritual experience

have the opportunity, if they so choose, to continue this experiential approach through the

use of the Godly Play presentations that have been developed for children up to age

twelve.

12

CHAPTER TWO

THE STATE OF THE ART IN UNDERSTANDING CHILDRENS

SPIRITUALITY

Overview

The theoretical foundation of this paper was developed by researching Biblical,

Historical, and Theological literary sources, together with additional research in the areas

of child development, education, psychology, psychiatry and neurology, plus recent

seminal research in the area of childrens spirituality.

The author sought to integrate information from the basic three sources of

foundational work for seminary research with what is known from other disciplines about

children and their development in order to reach a new level of understanding about the

spiritual nature of children. It is the belief of this author that an interdisciplinary approach

to childrens spirituality has the potential to open up interdisciplinary communication in

new ways that will increase the opportunity for theologians to make a timely, meaningful

contribution to the world regarding the moral and ethical challenges facing the global

community today.

It was noted by the researcher that Christian Education, as commonly practiced

today, is founded on educational theory that is based on cognitive learning, and does not

offer much information in the realm of inner, spiritual knowing. J ohn H. Westerhoff III,

13

in his book,Will Our Children Have Faith

1

, traces the development of Christian

Education practices during the last century to show how, in following education theory

that concentrated on effective teaching strategies, some of the fundamentals of inner faith

development have been lost. (There are some current exceptions to this general thrust,

such as practitioners who follow the inner-based work of Donald B. Rogers, Ph.D. author

of In Praise of Learning

2

or Wynn McGreggor, author of The Way of the Child

3

to name

two leaders in Christian Education who have long recognized the importance of

experiential learning and heart-based knowledge.) The basic assumption of many who

practice Christian Educationan assumption with which this author disagreesis that

children under the age of twelve are not capable of knowing because their cognitive

and rational skills are not yet developed. This assumption grew during the 1960s from

the work of Ronald Goldman, whose books Readiness for Religion

4

and Religious

Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence

5

claimed that children almost never have direct

experience of the divine, and who recommended that the Bible not be taught until age

twelve.

Three important practitioners were identified who worked directly with children

and who have contributed immensely to the understanding of the spiritual nature of

1

J ohn H. Westerhoff III, Will Our Children Have Faith (New York: Seabury Press, 1976).

2

Donald B. Rogers, In Praise of Learning (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 1980).

3

Wynn McGregor, The Way of the Child (Nashville: Upper Room Books, 2006).

4

Ronald Goldman, Readiness for Religion (London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul and

Seabury, 1965, 1968, 1970).

5

Ronald Goldman, Religious Thinking from Childhood to Adolescence (London: Routledge &

Kegan Paul, 1964).

14

children. Dr. Maria Montessori was a physician who began working in Italy with children

in about 1900; Dr. Sophia Cavalletti was a Hebrew Scholar who became interested in

Montessoris work and further developed her own approach as she tested her theories and

methods on several continents with children of all economic classes. An American, Dr.

J erome Berryman, later studied under Cavalletti and developed an ecumenical approach

for introducing children to the language and ritual of Christianity, which he called Godly

Play.

Finally, the author drew extensively on her own classroom experience and

background in the field of child development and family relationships as she

conceptualized the classroom environment that would be the setting for this research.

Biblical Foundation

In order to establish the biblical foundation for this work, The Hebrew Testament

was found to document the tremendous value placed on children in the stories told by the

ancient prophets. The birth of children was a treasured sign of Gods blessing to the early

Hebrews and throughout J ewish history.

Reflecting about J esus understanding of children as described in the Gospels, and

noting the positive attitude of J esus toward children as described by J ans-Reudi Weber in

Jesus and the Children

6

and by J erome Berryman in Godly Play

7

and How to Lead Godly

Play Lessons,

8

the author found congruency between the messages of these authors and

6

J ans-Reudi Weber, Jesus and the Children (Geneva: World Council of Churches, 1970).

7

J erome W. Berryman, Godly Play (Minneapolis: Augsburg, 1991).

15

Mathew Foxs Biblical interpretation entitled Original Blessing.

9

This led to the

exploration of an alternative viewpointthat of St. Augustines doctrine of original sin.

Resources used include Gerald Bonners St. Augustine of Hippo: Life and Controversies

10

and Augustine: The Confessions,

11

as well as Augustines own The Confessions of St.

Augustine,

12

and Basic Writings of St. Augustine.

13

Historical

The next step was to trace the historical attitude of Christians toward children,

from antiquity up to the present time. Cultural influences from ancient Hebrew and

Greco-Roman cultures were examined using the above-mentioned work of J ans-Reudi

Weber. The Child in Christian Thought, edited by Marcia J . Bunge

14

is a significant

collection of essays that point to a developing theology of children, tracing the history of

8

J erome W. Berryman, How to Lead Godly Play Lessons: The Complete Guide to Godly Play

(Denver: Living the Good News, 2002).

9

Matthew Fox, Original Blessing (Santa Fe: Bear & Company, 1983).

10

Gerald Bonner, St. Augustine of Hippo: Life and Controversies (Norwalk: The Easton Press,

1995).

11

Gilliam Clark, ed., Augustine: The Confessions (Exeter: B, 2005).

12

St. Augustine, The Confessions of St. Augustine, trans. Rex Warner (New York and

Scarborough: The New American Library of World Literature, 1963).

13

Whitney J . Oates, ed., Basic Writings of St. Augustine (New York: Random House, 1948).

14

Marcia J . Bunge, ed., The Child in Christian Thought (Grand Rapids/Cambridge: William B.

Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2001).

16

how children have been viewed from the time of J esus to the present. The writings of

major theologians including J ohn Crysostom, St. Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Martin

Luther, J ohn Calvin, J ohn Wesley, J onathan Edwards, Friedrich Schleiermacher, Horace

Bushnell, Karl Barth and Karl Rahner, were scrutinized by the essay authors for their

views about children. Families in the New Testament World, by Carolyn Osiek

15

and

David L. Balch, and The Rise of Christianity by Rodney Stark

16

reflected new

information based on relatively new archeological findings and provided considerable

insight into the actual lives of families and children during Early Christianity.

Additional research on the history of childhood revealed a fascinating change

over time in the way society sees children. Phillip Aries classic, Centuries of

Childhood

17

was understood for years to say that children of medieval times were very

distant from parents and that childhood was not even recognized as a stage different from

adulthood. However, the book is now believed to have been misinterpreted due to an

erroneous translation. Now there is a much more refined understanding of how children

have been viewed at different times in history, based on more diverse research extending

beyond literature to include archeological and other sources of evidence. This change in

perspective was found in such works as O.M. Bakkes When Children Became People,

18

15

Carolyn Osiek and David L. Balch, Families in the New Testament World (Louisville, KY:

Westminster J ohn Knox Press, 1997).

16

Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity (San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1997).

17

Philippe Aries, Centuries of Childhood, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Alfred A. Knopf,

1962).

18

O.M. Bakke, When Children Became People (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005).

17

Nicholas Ormes Medieval Children

19

, Shulamith Shahars Childhood in the Middle

Ages,

20

and Steven Ozments When Fathers Ruled: Family Life in Reformation Europe.

21

An unusual firsthand account by a young mother from the Middle Ages, entitled The

Mothers Legacy to her Unborn Child,

22

provided poignant insight about religious

attitudes toward parenting during that time. An article by Hugh Cunningham entitled

Histories of Childhood, published in a 1998 issue of The American Historical Review,

23

provided a summary of historical attitudes toward children in America.

Theological

There has been very little written by Christian theologians about children since

the time of Augustine. J ohn Comenius (15901670), who wrote The Labyrinth of the

World and the Paradise of the Heart

24

is an exception. J ohn Wesley (170391) addressed

the issue of the religious education of children in the eighteenth century,

25

and Horace

Bushnell wrote the first extensive work on the religious lives of infants and children,

19

Nicholas Orme, Midieval Children (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001).

20

Shulamith Shahar, Childhood in the Middle Ages (London and New York: Routledge, 1990).

21

Steven Ozment, When Father Ruled: Family Life in Reformation Europe (LCambridge and

London: Harvard University Press, 1983).

22

Elizabeth J oscelin, The Mothers Legacy to her Vnborn Childe, ed. J ean Ledrew Metcalfe

(Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2000).

23

Hugh Cunningham, Histories of Childhood, The American Historical Review 103, no. 4

(October 1998).

24

J ohn Comenius, The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, trans. Howard

Louthan and Andrea Sterk (New York: Paulist Press, 1997).

25

Stanley C. Finley, In Nature's Covenant (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press,

1992), hhtp:www.victorianweb.org/religion/wchild.html. (accessed April 3, 2006).

18

entitled Christian Nurture,

26

in 1861. Twentieth century theologian Karl Barth included

a section entitled Parents and Children in his Church Dogmatics,

27

and Catholic

theologian Karl Rahner wrote one essay entitled, Ideas for a Theology of Childhood.

Rahners writing, though not extensive, had a major impact on Catholic religious

education after Vatical II, and his theology is used to ground the work of later research by

Hay and Nye on the spirituality of children.

Spiritual Practitioners

The work of three practitioners who worked directly with childrenbeginning

with Maria Montessori in the early 1900s, and Sophia Cavelletti and J erome Berryman

who are contemporarieswas reviewed in order to discover the wealth of knowledge

uncovered by these researchers through close observations of children of all classes in

many cultures. These practitioners have nurtured children for many years, testing their

theories and methods regarding the spiritual nature of children. Montessoris The

Montessori Method,

28

Gianna Gobbis Listening to God with Children,

29

which applies

the Montessori Method to the Catechesis of Children, Cavallettis The Religious Potential

26

Margaret Bendroth, Horace Bushnell's Christian Nurture, in Children in Christian Thought,

ed. Bunge, Marcia J (Grand Rapids/Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2001).

27

Mary Ann Hinsdale, Infinite Openness to the Infinite, in The Child in Christian Thought, ed.

Bunge, Marcia J (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co, 2001).

28

Maria Montessori, The Montessori Method (New York: Schocken Books, 1964).

29

Gianna Gobbi, Listening to God with Children, trans. Rebekah Rojcewicz (Loveland, OH:

Treehaus Communications, Inc., 2002).

19

of the Child,

30

and Berrymans Godly Play, Teaching Godly Play,

31

and The Complete

Guide to Godly Play

32

were the major resources consulted.

Developmental psychologist J ames W. Fowlers book, Stages of Faith

33

was also

reviewed, with particular emphasis on the first stages relating to childhood.

Other authors whose descriptions of their direct experience with children provided

insight into the spiritual nature of children, include Catherine Maresca

34

, Peggy J .

J enkins, Ph.D.,

35

Barbar Kimes Myers,

36

Rev. Dr. Suzi Robertson,

37

Polly Berrien

Berends,

38

Vivian Gussin Paley,

39

Cari J ackson,

40

and Patricia H. Livingston.

41

30

Sofia Cavalletti, The Religious Potential of the Child, trans. Patrica M. Coulter and J ulia M.

Coulter (Chicago: Liturgy Training Publication, 1992).

31

J erome W. Berryman, Teaching Godly Play: The Sunday Morning Handbook (Nashville:

Abbington Press, 1995).

32

J erome W. Berryman, The Complete Guide to Godly Play (Denver: Living the Good News,

2002).

33

J ames W. Fowler, Stages of Faith (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1981, 1995).

34

Catherine Maresca, Double Close (Loveland, OH: Treehaus Communications, Inc, 2005).

35

Peggy J . J enkins, Nurturing Spirituality in Children (Hilsboro, OR: Beyond Words Publishing,

Inc., 1995).

36

Barbara Kimes Myers, Young Children and Spirituality (New York and London: Routledge,

1997).

37

Suzi Robertson, Windows into the Spirituality of Children (none listed: Booksurge, 2006).

38

Polly Berrien Berends, Gently Lead (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc, 1991).

39

Vivian Gussin Paley, The Kindness of Children (Cambridge and London: Harvard University

Press, 1999).

40

Cari J ackson, The Courage to Listen (Minneapolis: Augsburg Books, 2003).

41

Patricia H. Livingston, This Blessed Mess, (Notre Dame, IN: Sorin Books, 2000).

20

Two recent editions of the Sewanee Theological Review

42

provided an overview

of recent theological reflection on childhood by such authors as J erome Berryman,

Marcia Bunge, Catherine Maresca, J oyce Ann Mercer and others.

Child Development, Psychology, Education and Brain Research

Child Development: Principles and Perspectives by J oan Littlefield Cook and

Greg Cook

43

was a resource used for a theoretical framework from the field of child

development. Included were sections on cognitive development including Piagets stages

of cognitive development and Vygotskys socio-cultural view of cognitive development.

Other resouces were Touchpoints, by T. Berry Brazelton, M.D.,

44

and Piagets Theory of

Cognitive and Affective Development, by Barry J . Wadsworth

45

. Diane Trister Dodges

book, The Creative Curriculum for Preschool

46

and Thelma Harms Early Childhood

Environment Rating Scale

47

provided general information for creating an appropriate

classroom environment for preschoolers.

42

Children and the Kingdom: Theological Reflections on Childhood, and Children and the

Kingdom: Education and Formation, Sewanee Theological Review, vol. 48, nos. 1(Christmas 2004) and

2(Michaelmas 2005).

43

J oan Littlefield Cook and Greg Cook, Child Development: Principles and Perspectives

(Boston: Pearson Education, Inc, 2005).

44

T. Berry Brazelton, Touchpoints (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co, 1992).

45

Barry J. Wadsworth, Piaget's Theory of Cognitive and Affective Development (New York,

1989).

46

Diane Trister Dodge, Laura Colker and Cate Heroman, The Creative Curriculum for Preschool

(Washington, DC: Delmar Thomson Learning, 2002).

47

Thelma Harms, Richard M. Clifford and Debby Cryer, Early Childhood Environment Rating

Scale (New York: Teachers College Press, 1998).

21

The work of neuroscientist and child psychiatrist Dr. Bruce Perry

48

provided

practical insight from recent brain research. His groundbreaking techniques of working

with highly traumatized children and listening to them for guidance as to what they need

for healing mirrors the principles and practices of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture. Dr.

Stanley Greenspans Infancy and Early Childhood

49

was useful in understanding the

formation of relationships with infants and young children.

Research on Childrens Spirituality

It is noteworthy that some of the first interest in researching the spiritual nature of

children came from the field of zoology. Following the interest of English zoologist

Alister Hardy, who hypothesized that spiritual awareness has evolved through a process

of natural selection because it has survival value for the individual human, Englishman

Edward Robinson interviewed more than 4,000 adults to inquire about their recollection

of spiritual experiences as children. He reported his findings in The Original Vision.

50

Robert Cole, an American child psychiatrist, took the next step by interviewing and

collecting art from children all over the world as he endeavored to discover their religious

and spiritual experiences, the way they see the world and how they make meaning.

48

Bruce D. Perry and Maia Szalavitz, The Boy Who was Raised as a Dog (Cambridge: Basic

Books, 2006).

49

Stanley I. Greenspan, Infancy and Early Childhood (Madison, CT: Intnational Universities

Press, Inc, 1992).

50

Edward Robinson, The Original Vision (New York: Seabury Press, 1988).

22

Anecdotal descriptions of his research comprise his l992 publication, The Spiritual Life of

Children.

51

In the late 1990s British zoologist David Hay joined with Rebecca Nye to write

The Spirit of the Child,

52

which reported their findings from interviews with thirty-eight

children. Of these, twenty-eight had no religious affiliation, three were from the Church

of England; four were Muslim and two were Roman Catholic. This seminal research

provided the definition of spirituality and defined the dimensions of spirituality used in

analyzing the results of The Grandpa Program.

It is clear from the dearth of information on the subject of childrens spirituality

that this is an area of study in great need of further investigation. The fact that the most

recent work in this area has been conducted by zoologists, rather than theologians, speaks

to the pressing need for much more involvement by theologians and church leaders. It is

apparent that there is an important role for theologians to play in an interdisciplinary

approach as the world presses forward with efforts to reach self understanding and peace

around the globe. The study of children offers a fresh, eye-opening approach that appears

to offer much promise.

51

Robert Cole, The Spiritual Life of Children (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1990).

52

David Hay and Rebecca Nye, The Spirit of the Child (London: HarperCollins, 1998).

23

CHAPTER THREE

THEORETICAL FOUNDATION AND REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Biblical Foundation

Blessing Based Spiritual nurture assumes a state of original blessing, rather than

one of original sin. Original blessing refers to Gods gift of creationthe earth, and

everything that exists, including humanity. Although Genesis and the first creation story

existed as far back as the ancient Hebrew tradition and J udaism, there was no doctrine of

original sin until it was developed during the fifth century. This doctrine was based on the

second creation story, from the writing and thinking of a bishop from Africa, St.

Augustine of Hippo, in the fifth century AD. Unfortunately, in spite of early

disagreements about the validity of this doctrine, it became the basis of a fall/redemption

theology that was bound up in an assumption of natural depravity of children that is still

carried over by some Christians to the present day.

There are six foundational pillars which under gird the Grandpa Program of

Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture. They are listed in order below, along with a description

of the biblical foundation for each pillar.

I. Children are a blessing because they are a gift from God.

24

God created man in his image;

in the divine image he created him;

male and female he created them.

God blessed them, saying to them: Be fertile and multiply, fill the

earth and subdue it. . .

(Genesis 1:27, 28)

1

Biblical scholars such as Herbert Hagg, former president of the Catholic Bible

Association of Germany and author of Is Original Sin in the Scripture? agrees with

Matthew Fox, author of Original Blessing,

2

that original sin is not found in the Bible.

Hagg states that:

The doctrine of original sin is not found in any of the writings

of the Old Testament. It is certainly not in chapters one to three of

Genesis. This ought to be recognized today, not only by Old

Testament scholars, but also by dogmatic theologians. . . . The idea

that Adams descendents are automatically sinners because of the

sin of their ancestor, and that they are already sinners when they

enter the world, is foreign to Holy Scripture.

3

The concept of children as a blessing is inherent in ancient Hebrew and J ewish tradition.

The birth of children was part of Gods covenant with his people, as illustrated in the

stories of Abraham and Sarah and Elkanah and Hannah, where both women who were

beyond normal child bearing age were blessed with children who eventually became the

nation of Israel from whom King David descended. And, eventually, the blessing of the

baby J esus became the ultimate blessing of God to his people.

II. Children are innately spiritual, i.e., they have a natural sense of God.

1

All references to the Bible are from the New American Bible (NAM) unless otherwise stated.

2

Matthew Fox, Original Blessing (Santa Fe: Bear and Company, 1983).

3

Ibid., 47.

25

After J esus cleansed the temple of the money changers, and was healing people,

the chief priests and scribes became upset when they heard the children shouting their

support for J esus:

But when the chief priests and scribes saw the amazing things

that he did, and heard children crying out in the temple, Hosanna

to the Son of David, they became angry and said to him, Do you

hear what these are saying? J esus said to them, Yes, have you

never read, Out of the mouths of infants and nursing babies you

have prepared praise for yourself? (Matthew. 21:1516)

J erome Berryman points out in his book about Godly Play that the children were aware

intuitively of things the chief priests and scribes could not fathom. J esus was most likely

referring to Psalm 8:2: Thou whose glory above the heavens is chanted by the mouth of

babes and infants. . .

4

Another time J esus refers to the knowingness of children is in the following passages:

At that time J esus said, I thank you, Father, Lord of

heaven and earth, because you have hidden these things from the

wise and the intelligent and have revealed them to infants, yes,

Father, for such was your gracious will. (Matthew 11:2526)

I thank you, Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because you

have hidden these things from the wise and the intelligent and

revealed them to infants; yes, Father, for that was your gracious

will. (Luke 10:21)

In the Matthew citation, the quote comes after the disciples from J ohn the Baptist

came to verify who J esus was. The point of the quote is that J esus is as approachable as a

4

J erome W. Berryman, The Complete Guide to Godly Play (Denver: Living the Good News,

2002), 129.

26

child, as compared with coming into the presence of a high priest, King Herod, or Caesar.

In other words, it was very easy to relate to J esus.

5

In Luke, a similar quote follows the return of the 72 disciples whom J esus had

sent off to do their work. As they returned, rejoicing in childlike wonder at their power,

J esus cautioned them to never focus on this power as their own. The implication is that

divinity is revealed to young children by intuition or to childlike (not childish) adults.

6

III. Every child needs to be heard by others in order to affirm his or her being;

therefore listening to a child is a holy act.

Two scriptures support this pillar.

Whoever receives one of these little ones in my name receives me

(Matthew 18:5)

For when two are gathered in my name, there I am in the midst of them.

(Matthew 18:20)

When we listen to children, knowing that Christ is presentwithin them and within us

we are receiving them in Christs name. J esus always had time to listen to children, as

evidenced by his rebuke to the disciples when they tried to keep the children from

disturbing him:

Let the little children come to me; do not stop them; for it is to such as these that

the kingdom of God belongs. (Matthew 19:1315)

IV. Children are fully human persons in their own right, not adults in the making,

blank slates, or pieces of clay to be molded.

5

Ibid., 130.

6

Ibid., 130.

27

In contrast with the surrounding pagan culture of the day where children were

viewed as less-than-human property, J esus believed children to have intrinsic worth.

The Scripture passages that emphatically proclaim the value and worth of children are

referred to by J erome Berryman as the millstone texts. Written as quotes from J esus,

they warn of the life and death consequences that will come to anyone who harms

children.

If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little

ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great

millstone were fastened around your neck and you were drowned

in the depth of the sea. Woe to the world because of stumbling

blocks! Occasions for stumbling are bound to come, but woe to

the one by whom the stumbling block comes! If your hand or your

foot causes you to stumble, cut it off and throw it away, it is better

for you to enter life maimed or lame than to have two hands or two

feet and to be thrown into eternal fire. And if your eye causes you

to stumble, tear it out and throw it away; it is better for you to enter

life with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into the

hell of fire. (Matthew 18: 69)

If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little

ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great

millstone were hung around your neck and you were thrown into

the sea. If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off; it is better

for you to enter life maimed than to have two hands and to go to

hell, to the unquenchable fire. And if your foot causes you to

stumble, cut it off; it is better for you to enter life lame than to have

two feet and to be thrown into hell. And if your eye causes you to

stumble, tear it out; it is better for you to enter the kingdom of God

with one eye than to have two eyes and to be thrown into hell,

where their worm never dies, and the fire is never quenched. (Mark

9:4248)

J esus said to his disciples, Occasions for stumbling are bound to

come, but woe to anyone by whom they come! It would be better

for you if a mill stone were hung around your neck and you were

thrown into the sea than for you to cause one of these little ones to

stumble. (Luke 17:12)

It is clear from these texts that J esus not only recognized an intrinsic spirituality in

children, but also valued them highly.

28

V. The Blessing of Children Affirms their Self-hood in Relation to God.

It is apparent from observing children being blessed that they have a positive, observable

response to the physical act of being touched and told they are created by God, loved by

God, blessed by God, and that God is always with them. They show a calm, content,

happy joy when this ritual is repeated on a regular basis. This must have been known by

J esus when he told his disciples to Let the Children Come:

Then little children were being brought to him in order that he

might lay his hands on them and pray. The disciples spoke sternly

to those who brought them; but J esus said, Let the little children

come to me, and do not stop them; for it is to such as these that the

kingdom of heaven belongs. And he laid his hands on them and

went on his way. (Matthew 19:1315)

VI. Children are a means of grace, a vehicle through which God makes Gods self

known.

This statement is taken from the writing of theologist Pam Courture, in her book, Seeing

Children, Seeing God: A Practical Theology of Children and Poverty.

7

It supports J erome

Berrymans notion that the ontological appreciation of a child is deeply important for the

development of adult spirituality of the teacher or other adult, and that this appreciation

in turn supports the childs spirituality.

At that time the disciples came to J esus and asked, Who is the

greatest in the kingdom of Heaven? He called a child, whom he

put among them, and said, Truly I tell you, unless you change and

become like children, you will never enter into the kingdom of

heaven. Whoever becomes humble like this child is the greatest in

the kingdom of heaven. Whoever welcomes one such child in my

name welcomes me. (Mathew 18:15)

7

Pamela Courture, Seeing Children, Seeing God: A Practical Theology of Children and Poverty

(Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2000), 13.

29

What are some characteristics that J esus might be referring to when he uses the phrase,

like children? His reference to humbleness suggests that being open and trusting,

having a sense of wonder and discovery, wanting to please, and being willing to follow

are possible characteristics of children that J esus may have had in mind as he encouraged

adults to be like children in order to enter the kingdom. J ust being in the presence of

children creates an opportunity for adults to do as J esus suggests. It is a way to maintain

or renew a soft heart as one becomes more distant from ones own childhood.

Theological Foundation

The theological center of the entire approach of Blessing Based Spiritual Nurture

is its notion of original blessing, which replaces the doctrine of original sin so familiar to

orthodox Christianity. Some background information on these two concepts follows.

Consistent with the biblical interpretations of Matthew Fox and Herbert Hagg,

J ewish prophet Elie Wiesel says, The concept of original sin is not a J ewish one. Even

though the J ewish people knew Genesis for a thousand years before Christians, they did

not read original sin into it. The concept of original sin is alien to J ewish tradition.

8

Paul Alan Laughlins analysis of the story of the Fall reveals some interesting

facts about the interpretation of this story. The Fall is actually the later of two creation

stories found in the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures, the other being the description of

the seven days of Creation. In the Fall, the cunning (Hebrew translation is mentally

acute) serpent tells Eve the truththat she will not drop dead if she eats the fruit of the

8

Ibid.

30

tree, even though God has mislead her to believe that it is poisonous. He also tells her she

will gain moral knowledge from eating itwhich is what happens in the story. If anyone

is devious or less than truthful, it is God, not the serpent.

Laughlin suggests that rather than being the all-knowing and all-powerful God of

contemporary Christianity, God is portrayed in this story as a rather inept human of

masculine gender who cannot see the hiding couple and therefore has to first inquire

about their whereabouts, and then about whether they had eaten the fruit. This seems to

be a God of little forethought, if he expected them to choose good when they did not have

the understanding to do so, rather than an omnipotent, omniscient Being.

Nowhere in the story, Laughlin emphasizes, is the word sin mentioned. Nor can

the concept of sin be inferred by the actions of Eve or Adam, because until they ate the

fruit they did not have the ability to know right from wrong. For God to punish them so

inappropriately, for something they could not possibly understand, is like a parent harshly

punishing a toddler for helping himself to candy within his reach in the check-out lane!

What kind of a God would punish a small child with never-ending punishment in this

situation? What kind of a God would punish a serpent for all eternity, for telling the

truth? Righteous, just and loving are definitely not words that come to mind.

9

Laughlin points out that many Christians assume that the serpent represents Satan,

and that Eve sinned and then caused Adam to sin by their eating of the apple, thereby

condemning all of humanity to punishment by God forever more. How did this

interpretation come to be attached to a story that had been around for so long?

9

Paul Alan Laughlin, Remedial Christianity (Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2000), 149154.

31

The concept of original blessing is related to the earlier creation story found in

Genesis. The original blessing was Creation, when God created the heavens and earth and

everything else. This original blessing occurred at the Beginning, as a gift from God that

includes humanity as part of the gift. Children, then, are perceived to be a blessing when

they are born. This creation-centered tradition began in the 9

th

century B.C. with the

Yahwist (J ) sources, the psalms, the wisdom books, the prophets, J esus and much of the

New Testament, and St. Irenaeus (c. 130200 A.D.)

10

The Christian interpretation of the Fall had its beginning in the work of Paul,

within about 80 years of the death of J esus, followed by the work of St. Augustine, who

developed his doctrine of original sin in the 4

th

century C.E.

It is interesting to note that with the acceptance of this doctrine, Christianity

portrays the most negative image of human nature of any of the major religions of the

world. By contrast, Eastern religions originating in China and India tend to view the

human predicament in terms of ignorance, not sin. The other two God-based religions of

J udaism and Islam perceive sin as an offense to God which can be atoned for through

repentance and reform or through ritualistic acts. However, based on the interpretations

of Paul and St. Augustine, Christianity has viewed sinfulness as a universal human

condition passed on to all of humanity through the sins of Adam and Eve.

11

10

Matthew Fox, Original Blessing, 11.

11

Ibid., 155.

32

Saint Augustine

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo (354430 CE) developed the doctrine of original sin,

stating, Whence it comes to pass that each man, being derived from a condemned stock,

is first of all born of Adam evil and carnal, and becomes good and spiritual only

afterwards . . . .

12

. From this he developed the related doctrine of total depravity, which

teaches that humans are born with the inability to choose, on their own, good over evil.

Only God can overcome this inability by providing divine grace as a way of salvation.

Born the son of a Christian woman and a pagan man, he wrote his Confessions, which

includes a description of his personal investigation of his own sinfulness regarding

sexuality and other transgressions. His effort to recall his own nature when he was very

young drew him to observe infants being breastfed. He noticed that even infants can

show jealousy when one is getting fed while another waits, and took this to be a

confirmation of his belief in the depravity of infants.

13

At the time Augustine developed his doctrine of original sin, it was opposed by a

monk of the time named Pelagius:

Pelagius denied that Adams sin injured his descendants, or

that there was any transmission of his fault in consequence of his

transgression. The primal innocence of our first ancestor is

renewed in each of his descendants and thus any doctrine of

Original Sin is ruled out at the very beginning. Nor is physical

death a penalty and a result of the Fall, but a natural consequence

12

Whitney J . Oates, ed., Basic Writings of Saint Augustine (New York: Random House, 1948),

276.

13

Gillian Clark, Augustine: The Confessions (Exeter: Bristol Phoenix Press, 2005), 51.

33

of human life. Adams death was, however, a personal punishment,

inflicted upon him for having disobeyed Gods command.

14

In 431 C.E., The Council of Ephesus ratified the condemnation of Pelagius as

heretical, thereby allowing Augustines doctrine to officially prevail.

15

It was many

centuries before there was a loosening of the grip of this pervasive thinking in

mainstream Christianity. The remainder of this paper identifies some theologians who

reflect that loosening, and who have led the way to an alternative: a blessing based

theology of Christian nurture that is the antithesis of the doctrine of original sin.

Meister Eckhart

A medieval mystic of the fourteenth century (12601328), Meister Eckhart was a

member of a German Dominican monastery. Unusual for a mystic of this time, he was of

noble birth and well educated, having studied and taught in Paris before becoming a

monk. Although he was one of the most famous preachers of his time, his contemporaries

found him very difficult to understand. Part of this seems to be due to the ambiguity of

his description of his process or experience of the divine, which was perhaps not

differentiated enough from his writing about theology to be clearly understood. (This is

essentially the same differentiation that is so relevant to the purpose of this paper: there is

a difference between merely teaching children about religion, versus fostering their

14

Gerald Bonner, St. Augustine of Hippo: Life and Controversies (Norwalk: The Easton Press,

1995), 319.

15

B.B. Warfield, The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, ed. Philip Schaff (T & T Clark, 1884),

http://www.romancatholicism.org/ (accessed April 2, 2006).

34

personal experience of God.) For example, when Meister Eckhart was explaining how

one might achieve unity with God he used the following metaphor:

[The Christian can become] more intimate with God than a

drop of water in a vat of wine, for that would still be water and

wine; but here one is changed into the other so that no creature

could ever again detect a difference between them. (Talks 20)

Critics interpreted his description of unity to mean was the same as. Soon after his

death, he was accused by the church of teaching 28 errors, with his imagery of water and

wine being identified as heretical.

16

Eckhart felt that union with God was important because he believed that people

were created for union with God. He believed that Gods love draws people to him, and

that Gods grace translates Gods love into individual experiencewith grace being a

process rather than something stationary. Eckharts description of his method of

transformationthat of stripping away the distractions of the soul by the physical world,

thought, and emotional reaction, in order to reach the inner self that is then able to unite

with Godwas confusing to many who had trouble understanding his concept of inner

self and outer self.

17

One can see how later understanding in the field of psychiatry

and the concept of ego might have contributed to a better understanding of Eckhart by

his contemporaries.

Eckharts method of transformation included forgetting the body, will, and

knowledgeas well as space, time and self-consciousnessin order to connect with

16

Margaret R. Miles, The Word Made Flesh (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 2005), 193

196.

17

Ibid., 196197.

35

God. Once the stripping away or forgetting occurs in the simple stillness at the core of

the soul, a void is created that God is obligated to fill.

Do not imagine that God is like a carpenter who works or not,

just as He pleases, suiting his own convenience. It is not so with

God, for when he finds you ready, he must act. . . God may not

leave you void. That is not Gods nature. He could not bear it.

(Sermon 4)

Once this inner transformation is achieved, Eckhart describes how this transforms

ones experience of the physical world:

I am often asked if it is possible, within time, that a person

should not be hindered either by multiplicity or by matter. Indeed it

is. When this birth really happens no creature in all the world will

stand in your way, and what is more, they will all point you to God

and to this birth. . . . Indeed, what was formerly a hindrance

becomes now a help. Everything stands for God and you see only

God in all the world. (Sermon 4; emphasis added)

Eckhart further describes the result of this total transformation:

One may test the degree to which one has attained to virtue by

observing how often one is inclined to act virtuously rather than

otherwise. When one can do the works of virtue without preparing

. . . and bring to completion some great and righteous matter

without giving I a thought, when the deed of virtue seems to

happen by itself, simply because one loves goodness and for no

other reason, then one is perfectly virtuous and not before. (Talks

21, emphasis added)

When this process is completed, the intellect is again available, free from

irrelevant self-talk, and able to have pure and clear knowledge of divine truth. With

the unity of God and the human soul, any urge to evil is transformed into energy that is

available to do good. Eckhart sees this as the way evil is overcome, rather than through

the repression of evil urges or sin.

If you have faults, then pray to God often to remove them from

you, if that should please God, because you cant get rid of them

36

yourself. If God does remove them, then thank him; but if he does

not, then bear them for him, not thinking of them as faults or sins,

but rather as great disciplines, and thus you shall exercise your

patience and merit reward; but be satisfied whether God gives you

what you want or not. (Talks 23)

Eckharts notion of the true self being the individual self that relates to God had

a major influence on the Christian West, and led to the concept of individual religious

responsibility and authority that were articulated in the Reformation.

18

Comenius

J ohn Comenius (15921670) was a protestant bishop with the Moravian Unity of

the Brethren Church, and is considered to be the Father of Modern Education. Viewed as

a pastoral calling, education was for him a process by which people could be trained to

see beyond the apparent chaos of the world and discover the underlying harmony of

gods universe

19

His approach did not include a condemning version of original sin

and the vices of the world, but rather an acknowledgement of the duplicity and evil of the

world . . . and the contrast with the world when it focused on Christ at the center.

20

He

stressed the loving nurture of children, rather than beating them into submission, and he

approached learning by appealing to the natural interests of children while

acknowledging the value of play. In his manual written for parents, he states that Infants

are given us as a mirror in which we may behold humility, gentleness, benign goodness,

18

Ibid., 193198.

19

J ohn Comenius, The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, trans. Howard

Louthan and Andrea Sterk (New York: Paulist Press, 1997), 26.

20

Ibid.,53.

37

harmony, and other Christian virtues. The Lord himself declares, Except ye be

converted, and become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.

Since God thus wills that children be our preceptors, we owe them the most diligent

attention.

21

J ohn Wesley

J ohn Wesley, the 18

th

century Anglican clergyman and Christian theologian, is

recognized as the founder of the Methodism. A summary of Wesleys attitude toward

children has been done recently by Stephen Finley:

Wesley believed that man was by his very nature a mere

atheist. Children were, foremost, afflicted by natural atheism,

an atheism chiefly inherent in their innate capacity to enjoy and to

love nature. Thus, the wise parent was impelled to break their

will because such will would lead them to two damning desires:

the desire of the flesh and the desire of the eyes. Children

desired first to enjoy earthly happiness, to experience what

gratified the outward senses, such as taste or touch. More inimical

to their spiritual well-being was the complementary desire of the

eyes: the propensity to seek happiness in what gratifies the

internal sense, the imagination, either by things grand, or new, or

beautiful. Both desires for Wesley were only incriminating

evidence of a childs inclination to fatal error, that is, to be a lover

of the creature, instead of the Creator. Parents could only deepen

and harden such error by ascribing the works of creation to

nature, or by praising the beauty of man or woman or the natural

world. Hence children were to be brought up in extreme austerity

of diet and dress and were to be taught repeatedly how they were

fallen spirits. Such instruction would help them to realize that

they were more ignorant, more foolish, and more wicked, than

they could possibly conceive. From this method of education they

would emerge with firmly held conviction that their natural

21

Ibid., 62.

38

propensities were akin on the one hand to the devil and on the

other to the beasts of the field.

22

J ohn Wesleys attitude toward children reflects that of his mother, which is

illustrated by a quote from a letter she wrote to him: In order to form the minds of

children, the first thing to be done is to conquer their will.

23

In a sermon he gave

entitled On Obedience to Parents he states:

Why did not you break their will from infancy? At least, do it

now; better late than never. It should have been done before they

were two years old: It may be done at eight or ten, though with far

more difficulty. However, do it now; and accept that difficulty as

the just reward for your past neglect.

24

During Wesleys time, a theological debate about the nature of humanity, together