Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Coordination

Hochgeladen von

Srour0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

13 Ansichten7 SeitenResearch in Coordination

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

DOCX, PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenResearch in Coordination

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

13 Ansichten7 SeitenCoordination

Hochgeladen von

SrourResearch in Coordination

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als DOCX, PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 7

It is unanimously agreed that there is no equivalent to Quran.

Quranic expressions and structure are Quran bound, and

language bound as well. It cant be reproduce to match the

original in terms of structure, effect, and intentionality of source

text. Inaccuracies and skewing of sensitive information will

always be the by-product.

Many studies, theological, historical, and recently linguistic,

have tackled the issue of the untranslability of Quran. Abdul-

Raof, .so and so tackled the limits of translation of Quran

providing examples including; style, cultural voids,

morphological, syntactic, prosodic, and acoustic features.

The present work sets out to deeply discover the translation of

Arabic coordination particles in similar verses in Quran.

Coordination is significant linguistic element. It extends to

include rhetorical, coherent .

Quran translation is presented as a testing ground for the

practical application of Equivalence theory, on one hand, and

the rhetorical flaws as well as pragmatic losses resulted, on the

other hands. The main focus of the work is coordination

particles in the translation of Arberry and Zeidan from the

perspective of the following scopes; contrastive rhetoric CR,

pragmatic theory of implicature, as well as Equivalence theory.

The theoretical background is divided into two main sections;

review of previous studies, and thorough inspection of the

semantic-syntactic functions of coordination particles.

1.1 Equivalence theory

there is no agreement among translation theorists

concerning the accurate definition of equivalence.

1.2 CR

Similarly, Ostler' s (1987) stud y showed that in formal

Arabic prose, coordination between phrases and sentences

represents an essential means of establishing cohesion in

text. She points out that Arabic rhetoric places high value

on parallel and balanced constructions of phrases and

sentences and that coordinating conjunctions, such as and

and or are employed to link any type of parallel structures,

e.g. nouns, verbs, phrases, and sentences. Ostler further

demonstrated that compared to the discourse organization

and the

syntactic structures of essays written by NSs, the L2 writing of

Arabic-speaking students contain s a particularly high number of

parallel structures, such as

main and dependent clauses and complex strings of adjective,

verb, and prepositional phrases . Other researchers, such as

Sa'adeddin (198 9),

commented that colloquial Arabic relies on repetition of ideas

and lexis, as well as frequent uses of coordinators as sentence

and phrase connectors for

rhetorical persuasion . Sa'adeddin noted that the L2 writing of

many Arabic speaking students demonstrates the transfer of

cohesive features common in their colloquial language use.

They found out that: Arabic employ significantly higher

median rates of sentence

transitions to establish cohesive textual structure. However, the

uses of sentence

transi tion s in L2 text s do not necessarily mark a contextu

alized flow of

information when sentence transition s are intended to identify

the meaningful

relationship of ideas in discourse.

(Hinkel, 2001)

Research in contrastive rhetoric is not exclusively European and

American. In addition to the publication of numerous empirical

studies

of Arabic-English contrasts, Hatim (1997) and Hottel-Burkhart

(2000)

have produced contributions to contrastive rhetoric theory.

Hatim,

whose disciplinary interest is translation studies, made a major

study of

Arabic-English discourse contrasts, dealing with the typology of

argumentation

and its implication for contrastive rhetoric. The author is

critical of previous contrastive rhetorical research of Arabic,

which he

describes as being characterized by a general vagueness of

thought

which stems from overemphasis on the symbol at the expense of

the

meaning, or as analyzing Arabic writers as confused, coming

to the

same point two or three times from different angles, and so on

(p. 161).

Hatim acknowledges, however, that there are differences

between Arabic

and English argumentation styles and underscores the

importance of

explaining why these differences occur rather than just relying

on

anecdotal reporting about the differences.

According to Hatim (1997), orality has been suggested as

explaining

the differences between Arabic and Western rhetorical

preferences by

researchers such as Koch (1983). Koch has claimed that Arabic

speakers

argue by presentation, that is, by repeating arguments,

paraphrasing

them, and doubling them. Hatim admits that Arabic

argumentation may

be heavy on through-argumentation (i.e., thesis to be supported,

substantiation,

and conclusion), unlike Western argumentation, which,

according

to Hatim, is characterized by counterarguments (i.e., thesis to be

opposed, opposition, substantiation of counterclaim, and

conclusion).

Yet the key is that for Arabic speakers, Arabic texts are no less

logical than

texts that use Aristotelian, Western logic. To quote Hatim,

It may be true that this [Arabic] form of argumentation generally

lacks

credibility when translated into a context which calls for a

variant form of

argumentation in languages such as English. However, for

Arabic, throughargumentation

remains a valid option that is generally bound up with a host

of sociopolitical factors and circumstances, not with Arabic per

se. It is

therefore speakers and not languages which must be held

accountable.

(p. 53)

Hatims (1997) contribution to textual analysis of Arabic and

English

contrasts is signi. cant. He explains observed differences from

an empirical,

text analytic point of view. Yet, in well-meaning explanations

meant

to show the legitimacy of different styles of argument across

cultures,

Hatim ends up generalizing about preferred argument patterns.

And,

like Hinds (1987), who analyzed Japanese-English contrasts,

Hatim can

NEW DIRECTIONS IN CONTRASTIVE RHETORIC 501

become an easy target for those who object to cross-cultural

analysis

because of the danger of stereotyping.

Another signi. cant non-European contribution to the study of

contrastive

rhetoric has been made by Hottel-Burkhart (2000), who writes

that rhetoric is an intellectual tradition of practices and values

associated

with public, interpersonal, and verbal communicationspoken

or

writtenand it is peculiar to the broad linguistic culture in

which one

encounters it (p. 94). What is considered an argument in a

culture is

shaped by the rhetoric of that culture. Hottel-Burkhart refers to

the wellknown

interview of the Ayatollah Khomeni by the Italian journalist

Oriana Fallaci, analyzed by Johnstone (1986). In the interview,

Fallaci

used a logical argument supportable by veri. able facts.

Khomeni offered

instead answers based on the words of God and his Prophet (p.

98), in a tradition in which he was schooled. Johnstone found

differences

between the two styles of argumentation not only in content but

also in arrangement and style.

Interest in contrastive rhetoric in Arabic-speaking countries

resulted

in the biennial International Conference on Contrastive Rhetoric

at the

American University of Cairo, Egypt. In a volume of selected

conference

papers (Ibrahim, Kassabgy, & Aydelott, 2000), 13 chapters

discuss studies

that deal with distinctive features of Arabic, studies of Arabic-

English

contrasts, and contrastive rhetorical studies of Arabic-speaking

students

writing in English. The second Cairo conference, held in March

2001,

attracted presenters from neighboring countries as well as from

Europe

and Asia. (Connor, 2002)

1.3 Coordination

there are a number of evidences that justify the overuse of

coordination rather than subordination in Arabic.

Because information retrieval in oral cultures is memory-bound

(as opposed to memory-free in literate cultures), information

tends to be packaged in memory-aiding forms characterised by a

high degree of formal parallelism. In contrast, the memory-free

communication context in literate societies is marked by a

greater degree of phonological, lexical, and syntactic variation.

(b) Propositional development is predominantly additive in

oral cultures, while it is mainly subordinative in literate

cultures.

(c) Communication is largely context-based in oral cultures,

while it is predominantly text-based (text-sensitive) in literate

cultures. This is due to the greater measure of distance

between discourse participants in literate societies.

(d) Communication is mainly aggregative in oral cultures,

while it is largely analytic in literate societies.

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- From Firth to Halliday: The Development of Register TheoryDokument5 SeitenFrom Firth to Halliday: The Development of Register TheorySrourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Relevance of Register Analysis To TranslationDokument6 SeitenRelevance of Register Analysis To TranslationSrourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nominal GroupDokument3 SeitenNominal GroupSrourNoch keine Bewertungen

- There Was A SaviourDokument19 SeitenThere Was A SaviourSrourNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Arabic Noun Phrase FairDokument2 SeitenThe Arabic Noun Phrase FairSrour100% (1)

- ConjunctionDokument4 SeitenConjunctionSrourNoch keine Bewertungen

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Directions Language Interactive WorksheetDokument2 SeitenDirections Language Interactive WorksheetDankpsikoNoch keine Bewertungen

- STYLISTICS IntoDokument25 SeitenSTYLISTICS IntoДжинси МілаNoch keine Bewertungen

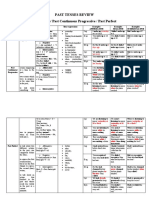

- Past Tenses Review Past Simple/ Past Continuous Progressive / Past PerfectDokument3 SeitenPast Tenses Review Past Simple/ Past Continuous Progressive / Past PerfectRuxandra03Noch keine Bewertungen

- Countable and Uncountable Nouns PDFDokument6 SeitenCountable and Uncountable Nouns PDFElvis huanca mamaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- English For Students of Physics - Vol 1Dokument8 SeitenEnglish For Students of Physics - Vol 1Ƨabah KhajehnejadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Verb Tenses ExplainedDokument8 SeitenVerb Tenses ExplainedAmy LaitilaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Sentences and Structure of A SentenceDokument5 SeitenSentences and Structure of A SentenceelmusafirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Left Recursion and Left FactoringDokument34 SeitenLeft Recursion and Left FactoringAdiba IspahaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nda E: Study Material For EnglishDokument7 SeitenNda E: Study Material For EnglishSadeeque PashteenNoch keine Bewertungen

- BLM 2 ConversationDokument10 SeitenBLM 2 Conversationfiasco_oNoch keine Bewertungen

- Category: Oral Presentation Rubric: Final ProjectDokument2 SeitenCategory: Oral Presentation Rubric: Final ProjectLuz Da GuerraNoch keine Bewertungen

- ELS 101 GrammarDokument45 SeitenELS 101 GrammarBryce VentenillaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 8 EnglishDokument80 Seiten8 EnglishvedhavarshiniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Worksheet 11: Future WillDokument2 SeitenWorksheet 11: Future WillJhauren0% (1)

- Interjection WorksheetDokument2 SeitenInterjection Worksheetapi-252729009Noch keine Bewertungen

- Join Yoursmahboob Official Youtube ChannelDokument975 SeitenJoin Yoursmahboob Official Youtube ChannelSiyyadri Bhanu Siva PrasadNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q1 Eng ExamDokument4 SeitenQ1 Eng ExamJade Yuri YasayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Giao An Ca Nam Anh 6Dokument306 SeitenGiao An Ca Nam Anh 6Hang TranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gerunds and Infinitives RulesDokument4 SeitenGerunds and Infinitives RulesMary LamadridNoch keine Bewertungen

- Apuntes de Gramática Ii - Unidad 1 - 2019Dokument48 SeitenApuntes de Gramática Ii - Unidad 1 - 2019ju4np1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Plans de Travail Sec.2 #2 (18 Mai) - 24000005 (6433)Dokument33 SeitenPlans de Travail Sec.2 #2 (18 Mai) - 24000005 (6433)Marilou PoirierNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schlegel F. - On The Language and Wisdom of The Indians 1849Dokument123 SeitenSchlegel F. - On The Language and Wisdom of The Indians 1849Sonia López50% (2)

- Grammar guide contentsDokument446 SeitenGrammar guide contentsPiyal Dev ChowdhuryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Catat Materi Ini.: Social FunctionDokument3 SeitenCatat Materi Ini.: Social Functionbudi hartantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 СОЧDokument62 Seiten10 СОЧАйдын КурганбаеваNoch keine Bewertungen

- Arbitrariness 4upDokument2 SeitenArbitrariness 4upEdwinRobertNoch keine Bewertungen

- AdjectivesDokument1 SeiteAdjectivesCarlosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Legend Structure and CharacteristicsDokument4 SeitenLegend Structure and CharacteristicsMaeda SariNoch keine Bewertungen

- Negative Prefixes: Un-Ir - Im - in - Dis - IlDokument2 SeitenNegative Prefixes: Un-Ir - Im - in - Dis - IlHelen Hodgson100% (1)

- Past Events SummaryDokument10 SeitenPast Events SummaryOrlando DelgadoNoch keine Bewertungen