Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin System

Hochgeladen von

Bilel Faleh0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

23 Ansichten19 SeitenThe verbal "pictures" in. John Hawkes's novels are unforgettable, provocative. Descriptions of an arid desert inhabited by giant snakes. A lyrical Illyria of no seasons, an anchorless, drifting ocean liner, and a car streaking toward destruction.

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Bettle Leg

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenThe verbal "pictures" in. John Hawkes's novels are unforgettable, provocative. Descriptions of an arid desert inhabited by giant snakes. A lyrical Illyria of no seasons, an anchorless, drifting ocean liner, and a car streaking toward destruction.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

23 Ansichten19 SeitenThe Board of Regents of The University of Wisconsin System

Hochgeladen von

Bilel FalehThe verbal "pictures" in. John Hawkes's novels are unforgettable, provocative. Descriptions of an arid desert inhabited by giant snakes. A lyrical Illyria of no seasons, an anchorless, drifting ocean liner, and a car streaking toward destruction.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 19

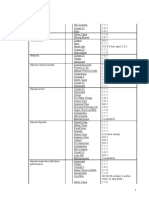

The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

A Newly Envisioned World: Fictional Landscapes of John Hawkes

Author(s): Carol A. MacCurdy

Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Autumn, 1986), pp. 318-335

Published by: University of Wisconsin Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1208348 .

Accessed: 13/04/2014 10:22

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

University of Wisconsin Press and The Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System are

collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Contemporary Literature.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A NEWLY ENVISIONED WORLD:

FICTIONAL LANDSCAPES OF JOHN HAWKES

Carol A.

MacCurdy

The verbal

"pictures"

in John Hawkes's novels are

unforgettable,

provocative

visions that have

perhaps

more

impact

on the reader than

any

other element in Hawkes's fiction.

Descriptions

of a

slumbering

insane

asylum,

an arid desert inhabited

by giant snakes,

an abandoned

lighthouse

amidst

sharp,

black

rocks,

a

lyrical Illyria

of no

seasons,

an

anchorless, drifting

ocean

liner,

and a car

streaking

toward destruc-

tion are all

powerful images

that dominate such other fictional ele-

ments as

plot, character,

or theme. Rather than

exploring

a

subject

or

pursuing

the location of

"truth,"

Hawkes wishes to

enthrall, cap-

ture,

and enchant the reader with the

intensity

of his vision. He chooses

not to offer an accurate

representation

of an

independent, pre-existing

reality

but insists on the creation

of,

in his

words,

"a

totally

new and

necessary

fictional

landscape

or

visionary

world"

("Interview"

with

Enck

141).

As Hawkes

explains

in his interview with John

Enck,

his novels

originate

with

pictorial "flickerings

in the

imagination,"

not with "sub-

stantial narrative materials or even with

particular

characters." He con-

tinues: "In each case what

appealed

to me was a

landscape

or

world,

and in each case I

began

with

something immediately

and

intensely

visual- a

room,

a few

figures,

an

object, something prompted by

the

initial idea and then

literally seen,

like the visual

images

that come

to us

just

before

sleep" (148).

This comment

suggests

that one

key

to Hawkes's

image-making

is his

ability

to

tap

the

dream-energy

resid-

ing

in his unconscious

mind;

he himself admits that his work is "satu-

rated with unconscious content"

("Hawkes

and Barth"

32).

Familiar

locales would crowd and inhibit his

imagination,

he

feels,

because

they

require

a semblance of the

representation

he eschews and would offer,

moreover, what he

regards

as

autobiographical entrapments.

He

Contemporary Literature XXVII, 3 0010-7484/86/0003-0318 $1.50/0

?1986 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

explains

to John

Enck, "my writing depends

on absolute

detachment,

and the unfamiliar or invented

landscape helps

me to achieve and main-

tain this detachment"

(154).

Fictional

landscapes

are thus at the center

of his fiction because

they

serve not

only

his

writing process

but also

his artistic raison

d'etre.

Taking

cues from Hawkes's

many

comments on the

subject,

most

critics have noted Hawkes's

handling

of

landscape

and have

analyzed

it in

light

of his

style,

narrative

experiments,

or structural

concerns.'

Hawkes's worlds often

get

lost in the

analysis

of the artistic

process;

the critical articles

primarily

focus on the role of the artist and his

imagination,

not on the final creative

product-the

fictional world.

Hawkes's

landscapes

are art

objects; they

are

thoroughly,

self-con-

sciously fictional,

self-contained

artifice,

tableau. These worlds are

the end result of the creative

process,

the

repository

of Hawkes's uncon-

scious,

as well as the source of his

writing.

What has not been well

understood is their

essentiality

to Hawkes's aesthetic and their devel-

opment

in

technique

and focus. Hawkes's

imaginary

worlds have

evolved since he first

published

in

1949,

and these

changes

reflect the

four distinct

phases

in his

literary

career:

1)

the use of

visionary

land-

scape

tied to

specific locales; 2)

the use of

landscape projected

out

of

first-person perspectives; 3)

the use of

landscape totally

contained

by psyches;

and

4)

the return - with a difference - of the

visionary

his-

torical

landscapes

found in

phase

one. A

study

of Hawkes's fictional

landscapes

demonstrates his continual

development

as a writer and

also clarifies his

evolving

world view.

Hawkes's insistence on

constructing private landscapes

results in

early

works of

"nearly pure

vision"

("Interview"

with Enck

149). Any

reader of

"Charivari,"

The Cannibal

(1949),

The Beetle

Leg (1951),

The Owl

(1954),

The Goose on the Grave

(1954),

or The Lime

Twig

(1961)

will attest to their visual brilliance as well as their difficult nar-

rative. Little sense of

plot progression emerges;

instead one finds

stunning

set

pieces

that dazzle the

imagination

while

disorienting

one's

perceptions.

These absolute visions

produce surrealistic,

dreamlike

effects. Each work

has, however,

or seems to

have,

an actual locale

for a

setting: "Charivari," England;

The

Cannibal, postwar Germany;

The Beetle

Leg,

the American

West;

The

Owl,

medieval

Italy;

The

'Tanner

suggests

that a

relationship

exists between Hawkes's

style

and his use

of

landscape (204-5);

Kuehl discusses the role

landscape plays

in the structure of the

novels

(xi).

HAWKEs 319

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Goose on the

Grave,

postwar Italy;

and The Lime

Twig, postwar

England. Although

the reader

may point

to a

place

on the

map

where

each book is

set,

the factual identification will be of little comfort.

Hawkes himself refers to these locales as his

"'mythic' England,

Ger-

many, Italy,

American west"

("Interview"

with Enck

154).

Some

recog-

nizable features of these

places exist,

but Hawkes undermines

any

sense

of

familiarity by distorting

the surface

reality.

In "Charivari" a cat

talks to a

seamstress; marauding dogs

board a

passenger

train and

become

paying

customers in The

Cannibal;

and a

giant

desert snake

strikes out the

headlight

of a

vacationing family's

station

wagon

in

The Beetle

Leg.

War dominates the

landscape

of Hawkes's novels between 1949

and 1964. Set in

post-World

War

II

England, Germany,

and

Italy,

these

locales seem standard World War

II fare, yet

Hawkes's hallucinated

vision makes the desolate

backgrounds

not

places

but

nightmares.

Rid

of most

signs

of

civilization,

the

primitive landscapes

seem timeless

reminders of war's

horrors,

a world void of reason and doomed to

annihilation. In The Cannibal Hawkes bestows

upon Germany

a com-

pletely fictional,

nonexistent

town, Spitzen-on-the-Dein,

a

setting

that

epitomizes

his

warscapes, especially

those in The Owl and The Goose

on the Grave.

Spitzen-on-the-Dein,

"shriveled in structure and as

decomposed

as an ox

tongue

black with ants"

(Cannibal 8),

is a debris-

ridden

village stripped

of

any civilizing

influence.

Using

the

metaphor

of a vulture or carrion

bird,

Hawkes

pictures

the town as a

giant

slum-

bering

fowl: "The

town, roosting

on charred

earth,

no

longer ancient,

S.

..

gorged

itself on

straggling beggars

and remained

gaunt

beneath

an evil cloaked moon"

(7).

This fatalistic

picture suggests

inevitable

human

extinction,

as do most of Hawkes's

early war-ravaged

land-

scapes.

All of Hawkes's fictions from "Charivari" to The Lime

Twig,

whether or not

they

are

war-related, present

such

apocalyptic

land-

scapes

bereft of

life-sustaining energies. Tony

Tanner

suggests

that

Hawkes's

"landscapes

of desolation and decline

...

point

to the

prog-

ress of

entropy quite

as

graphically

as the

landscapes

of

Burroughs

and

Pynchon" (203). Indeed,

each

setting

in the

early

work

conveys

.nothing

but waste and death. In The Cannibal nature itself has become

mutant or

exhausted;

this wasteland

yields only

"twisted stunted trees"

(37),

"bleached

plants" (6),

acidic earth that burns human

flesh,

and

cows that scratch for food with hare's teeth. In such a desiccated land-

scape

man likewise is

depraved,

as illustrated

by

the Duke's

eating

of

the

young boy. Entropic landscapes

underscore not

only

man's fall

320

I

CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

from innocence

but,

more

important,

his

plunge

into

nightmare.

For

example,

in The Beetle

Leg,

Gov

City

and its inhabitants live in the

shadow of obliteration as the manmade dam drifts

forward, promis-

ing again

the Great Slide. Instead of

being tamed,

the American fron-

tier is

hostilely swallowing up impotent cowboys.

In The Owl, the

medieval

town,

Sasso

Fetore, meaning

"Tomb

Stench,"

is a barren

fortress of

violence, sterility,

and death. In The Goose on the

Grave,

a

grim,

war-scarred

Italy

leaves an

orphan exposed

to the

degeneracies

of

failing

Western culture.

Clearly,

the terrain of a world in

shambles,

with such breaches of nature and violations of

humanity,

comments

on the condition of modern man.

These ominous

settings

not

only suggest

the state of their inhabi-

tants but also dominate them. Environment controls and circumscribes

human action. In The Cannibal the characters seem doomed to re-

capitulate

the

history

of their

war-ravaged

world. In The Owl the

townspeople

of Sasso Fetore are

subject

to the Owl's inhuman demands

just

as their town is dominated

by

his iron fortress. In The Beetle

Leg

the

great

silent desert renders minuscule the clustered human com-

munities. And in The Lime

Twig

Michael and

Margaret Banks,

children

of war and

lodgers

of

Dreary Station,

seem destined to

collapse

with

the dreams of a lost

generation. Imprisoned by

such hostile

landscapes,

people

become aimless creatures

somnambulating

across a

geography

that determines their behavior. Even the social institutions created to

give

order

inevitably

contribute to the

general collapse.

All the insti-

tutions in The Cannibal- the

asylum, University,

and

nunnery

- are

doomed to failure. Their commitment to the

preservation

of social

order ensures ruin because in this world the

apparent

order is war.

Rather than

impeding

the

surrounding

world's decline

through

the

imposition

of

controls,

the

existing

social institutions accelerate it.

Any

effort to control chaos

promotes only

an

entropic

decline into

deathly

uniformity

and stasis. Both modern man and his

environment,

there-

fore, promote entropy, which, according

to the second law of thermo-

dynamics,

results in an ultimate state of inert

uniformity.

Neither

nature nor man is

benign

and

ordered;

an

incipient

chaos

rages

in both.

Because both man and his environment are identified with the

potential

for

destruction,

no clash between

life-sustaining

and death-

oriented

impulses

occurs.

Humanity

is

just

as

corrupt

as the surround-

ing

world. No one can

stop

the Red Devils or the Great Slide. Domi-

nated

by

hostile

landscapes

until

they

become

part

of

them,

the char-

acters become identified with the

very

world in which

they

live. Such

an identification or

correspondence

between external nature and human

HAWKES 321

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

nature characterizes Hawkes's

early

novels. All

private

and

public

worlds

collapse;

all

energies

are

inverted, resulting

in death or destruc-

tion,

not

love, renewal,

or fulfillment. Given this

negation

and

empha-

sis on

death,

the

early

works offer no conflict between the forces of

life and death. At this

point

in his career Hawkes

speaks

of "the

latency

of destructive force" instead of "the

possibility

of life-force"

("Inter-

view" with Graham

451).

As a

result,

characters

appear flat,

the nar-

rative remains

impersonal,

the structure is

circular,

the

images

are

death-ridden,

and the

settings

are

imprisoning.

A

tensionless,

inert

universe

reigns. Largely deterministic,

these dark

hallucinatory

land-

scapes suggest

Hawkes's

early

world view.

Beginning

in

1964,

Hawkes's

emphasis changes.

Rather than con-

centrating

on the

depiction

of a

dark, powerful world,

he

begins

to

stress modern man's reaction to chaos.

Trapped

in a

wasteland,

iso-

lated,

full of

anxiety,

and unable to

communicate,

man falls back

upon

himself. Because his external environment is not

congenial

to the

self,

he marks off the "inner" world from the "outer" world and turns

inward.

Starting

with Second

Skin,

Hawkes demonstrates the

change

by using

a

first-person point

of view. This shift in narration affects

the

presentation

of

landscape

and

signals

a new direction in Hawkes's

fiction. The earlier works' sense of stasis and

impersonality gives way

to

subjective

fictions with a dramatic form. The

storyteller impelled

by private

needs takes his own

personal history, decomposes it,

and

puts

it back

together.

His mind becomes an active

shaper

of his

world,

resulting

in novels that reflect the

dynamics

of the

fiction-making

process. According

to

Tony Tanner,

Second Skin marks an advance

in Hawkes's work because it offers "less of the stasis of

landscape

and

more of the motion of narrative"

(218).

Instead of

presenting dark,

authoritarian

worlds,

Hawkes offers

settings

that serve the narrators'

storytelling by dramatizing

their

struggle

with life and death. The

"plot"

of Second Skin and The Blood

Oranges

consists of the narrators'

creating lyrical landscapes

in

sensuous detail to offset the world's

threatening forces; settings

are

not

solely

besotted with the forces of death.

Discussing

Second

Skin,

Hawkes

acknowledges

for "the first

time,

I

think,

in

my

fiction that

there is

something

affirmative.

...

I

got very

much involved in the

life-force versus death"

("Interview"

with Graham

459).

The result-

ing

tension between these two

primal

forces

changes

the

topography

of the novels after The Lime

Twig

as Hawkes

increasingly

structures

322 I CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

his novels

through

the use of two

contrasting settings.

In Second Skin

two islands dramatize antithetical

experiences. Writing

his memoir from

a

floating tropical

island bathed in

sunlight

and

lushness, Skipper

seeks

refuge

from a

jagged,

barren island off the coast of Maine. Even in

the

magical country

of

Illyria

where

Cyril pursues

his love

idyll, Hugh's

dark

dungeon

of death awaits. In

Death, Sleep

& the

Traveler,

Allert's

mind moves from his

hot, sunny

sea

voyage

in the South to a

frigid,

snowbound chateau in the North. In these later works Hawkes's set-

tings express

structural

importance

as

they

dramatize the narrator's

struggle

with Eros and Thanatos.

In order to

convey

this inner conflict

through

the novel's land-

scape,

Hawkes uses

purely imaginative settings.

Searchers with

maps

will not locate

Skipper's floating

island or

Cyril's mythical Illyria

of

no

seasons; likewise,

Allert's whereabouts are unknown.

Skipper, Cyril,

Allert,

and

Papa

create their territories. Because of their destructive

pasts

and their

inability

to make sense of the

surrounding confusion,

the narrators concentrate the enormities of their

existence, consciously

shape

them into a

manageable environment,

and transform the brute

chaos into a fictional but

consciously patterned

world.

Leaving

the

death-haunted,

"black island in the

Atlantic," Skipper imaginatively

constructs his

"sun-dipped wandering

island"

(Skin 48), freeing

it from

geographical

restraints and himself from the

pains

of his

past.

Simi-

larly, Cyril brings Illyria

into

being

in

response

to the

question

asked

in the

epigraph (from

Ford Madox Ford's The Good

Soldier):

"Is there

then

any

terrestrial

paradise where,

amidst the

whispering

of the olive-

leaves, people

can be with whom

they

like and have what

they

like

and take their ease in shadows and in coolness?"

(Oranges epigraph).

The memoirs of these

first-person

narrators are fictional

projections

of both

mythical

worlds and identities

desperately trying

to

regain

a

sense of self. Stimulated

by

a fear of hostile forces as well as a desire

for a

serene, pleasurable existence, Skipper

and

Cyril creatively

resist

the excruciations of life and

actively produce

a

reality

that is consis-

tent with their

psychological

and creative needs. Their fictional land-

scapes

thus offer them

self-preservation,

aesthetic

satisfaction,

and

freedom

-

the freedom to create a world and an

identity

to their

liking.

Skipper

can be an artificial inseminator of

cows,

and

Cyril

can be a

sex-singer

in

Illyria.

As Hawkes

says

to John

Kuehl,

"what we all want

to do

...

is to create our own worlds in our own voice"

(qtd.

in Kuehl

157).

Hawkes's

first-person

narrators

produce

their fictional

landscapes

primarily

out of a

pastoral impulse.

Like

many

American

heroes, these

HAWKES 323

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

characters withdraw from

society

with its deterministic

limitations,

guilts, anxieties,

and enslavement to time.

Rejecting society's

bound-

aries and the burden of

history,

the

mythical

American hero

journeys

into a domain where an

unspoiled beauty

offers

psychic

renewal.

Hawkes's characters share the same desire for

security, repose,

free-

dom from the flux of

time,

and the

opportunity

for a

spontaneous,

instinctual life. However much

they may yearn

for an

unbounded,

timeless

world,

such an

idyllic pastoral setting

is unavailable in the

contemporary

world. The American fables of the

redemptive journey

into the wilderness told

by Cooper, Thoreau, Melville, Faulkner,

and

Hemingway

now arouse mere

nostalgia.

In his

study

of 1960s

fiction,

Raymond

Olderman

suggests

that the "old theme of the American

Adam

aspiring

to move ever forward in time and

space

unencumbered

by memory

of

guilt

or reflection on human limitation is

certainly

un-

available to the

guilt-ridden psyche

of modern man"

(9).

Even

though

the inherited

symbol

of a

pastoral

retreat or an

American Eden

may

evoke an ironic

response,

the

urge

for a world

remote from

history,

where nature and art are held in

balance,

still

exists. For

Hawkes, however,

the

possibility

for the establishment of

such a

pastoral

ideal is

through

the aesthetic

imagination.

The land-

scapes

themselves hold the

opposing

forces of life and

death;

it is there-

fore

up

to the narrators to create a fictive order. In

essence,

the nar-

rator's creation of a fictional

landscape

has become the

surrogate

for

a

pastoral ideal,

for within this self-created world

paradoxes

can be

aestheticized and therefore made tolerable. In the realm of

supreme

fiction man can

escape

the flux of time and the dualism between

internal and external

reality.

Hawkes's narrators thus

attempt

to

become Adamic heroes in the

garden

of their memoirs.

In Second

Skin,

Skipper's

memories of a

past

filled with death

and violence make

up

much of his "naked

history."

His

early

child-

hood lived out at his father's

mortuary,

his wartime

experiences,

and

his

stay

on the infernal black

island,

site of Cassandra's

suicide,

all

suggest

a world dominated

by

death. In

many ways

this fictional world

remains as death-oriented as the earlier

novels,

for the cruel

landscapes

formed

by Skipper's imagination compose

most of the novel's struc-

ture. Until

Skipper

reaches his unnamed

wandering island,

the land-

scapes

he travels harbor

nothing

but

inexplicable

malice. The affirma-

tion in the novel comes not from

Skipper's

environment but from his

redemptive imagination. Experiencing

both

psychic

extremes

- of Eros

and Thanatos, as illustrated

by

the two

alternating

islands -

Skipper

chooses life over death in an act of creative will. Even

though

death

324 I CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

exists on his

peaceful

island in the form of a

cemetery,

he illuminates

the dark

graveyard

with candles to

produce

an "artificial

day" (208)

and "to have a fete with the dead"

(206).

Not

denying

the

presence

of

death,

he

creatively

resists it and instills life

(creative passion)

into

the resistant forces of nature.

Likewise,

the narrator of The Blood

Oranges, Cyril,

tries to restore

his

shredding tapestry

of love from his

pastoral

retreat of

Illyria.

Choosing

the seacoast of

Shakespeare's Twelfth Night

as his

locale,

Hawkes

signals

the reader that

Cyril's country

resides in his

imagina-

tion,

like

Skipper's floating

island.

According

to

Hawkes, Illyria

"actually

consists of an arid

landscape"

that

Cyril

transforms into his

own erotic

idyll.

In his interview with Robert

Scholes,

Hawkes

explains

that

Cyril

"is

simply trying

to

designate

the

power, beauty, fulfillment,

the

possibility

that is evident in

any

actual scene we exist in. . . .

Illyria

doesn't exist unless

you bring

it into

being" ("Conversation" 203).

Skipper's

and

Cyril's pastoral

worlds are not restricted to a terrestrial

landscape

but

spring

from their

imaginative vitality;

the two narrators

vigorously pursue

the creative act. The fictional

landscapes

of Second

Skin and The Blood

Oranges

consist of the narrator's interior world

where the restrictions of time and

space

are

nonexistent,

where the

imagination reigns freely,

and where the

pleasure principle

is enshrined.

According

to Leo

Marx,

the "usual

setting

of

pastorals"

has been

a "never-never land"

(47);

in

keeping

with this

tradition,

Hawkes sets

his later novels in the "never-never land" of the

psyche. Nature,

the

destination of the

pastoral journey,

is no

longer

restricted in

meaning

to terrestrial

landscape

but can be defined as the

vitality

of uncon-

scious

experience. Following

Second

Skin,

each

succeeding

novel in

Hawkes's triad-The Blood

Oranges (1971), Death,

Sleep

& the

Traveler (1974), Travesty (1976)- goes

a

step

further in

banishing

the

rational external world to concentrate on the interior

journey

into the

psyche.

Hawkes's narrators reflect this

process

of

reduction;

external

landmarks and events become

increasingly

removed from the novel's

world. In the

triad,

Hawkes reduces

landscape

to

private, solipsistic

underworlds dominated

by

the narrator's unconscious needs and fears.

Whereas

Skipper consciously

uses his

imagination

in a

redemptive

act

of

creativity,

the other narrators

increasingly pursue

a destructive

course. In The Blood

Oranges Cyril

wreaks havoc on his terrestrial

paradise by attempting

to force others into his

tapestry

of love. In

Death, Sleep

&

the Traveler Allert floats in his anchorless

ship

on his

HAWKES

325

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

own

psychic

waters until he is so

remote, detached,

and obsessed that

he exists

solely

in his dreams. And in

Travesty Papa

confines himself

to the interior of his car as he

speeds

toward suicide and murder. As

Hawkes charts the narrator's inner

migration,

the destination becomes

increasingly ambivalent,

for the unconscious

simultaneously

offers

freedom and annihilation.

The characters'

complete

isolation in their own inner

landscapes

emphasizes

the

danger

of such

imprisonment.

Like characters in the

early novels, they

too are

imprisoned by

their environments. The dif-

ference is that

they

are ensnared

by projects

of their own

making.

No

longer

casualties of outer

forces, they

have become victims of their

own internalization - victims of their own

psyche.

The artistic

imagina-

tion when

impelled by

a disturbed

psyche

can

shape

a diminished or

nightmarish

world rather than a coherent one.

According

to Frank

Lentricchia,

"the

telling sign

of such self-destructive consciousness is

its

monolithic, absolutizing

character" where

"single

vision

reigns"

(157). Only

in

Skipper's

Second Skin do the

conflicting

forces of life

and death coexist. This healthful reconciliation results from the crea-

tive mind's

ability

to transform the

unintelligible

into a fictive order.

In contrast to

Skipper's

"naked

history," Cyril's tapestry,

which

is also an artistic

design,

is in

shreds; Illyria

is

coming apart

at the

seams because of

Cyril's singleness

of vision.

Ironically,

his

tapestry,

rather than

weaving together

the

opposing threads,

unravels to reveal

the

polarity

in his

pastoral

scene. When

Hugh,

an alien to

Illyria,

comes

over the mountains and

brings

with him the

repressive

forces of civili-

zation, Cyril

is unable to

incorporate Hugh's

"alien

myth"

into

Illyria.

Hawkes

suggests

that

Hugh

is not the

only

character

guilty

of sub-

verting

life into a

rigid

order.

Cyril's

effort to raise sexual

activity

-

a

natural

process

-

to an art form

promotes

disaster.

Although

his sexual

theorizing

is an

attempt

to

compose

the

merging paradoxes,

no erotic

harmony

results. Insistent on the

supremacy

of his

vision, Cyril

fails

to balance the

paradoxes

of Eros and Thanatos. The Blood

Oranges

therefore remains

Cyril's

version of a failed

pastoral.

Another narrator who

struggles

to create a world that will sus-

tain his

imagination

is Allert in

Death,

Sleep

& the

Traveler;

his

imagi-

nation, however,

leads him to demons. As an

artist,

Allert's aesthetic

achievement lies

solely

in the creation of his

dreams,

but no

lyrical

affirmation resides in his

nightmares.

Allert's descent into his

psyche

is enacted on a

large

scale when he takes an uncharted ocean cruise.

The novel consists of his interior

journey

into the oceanic

depths

of

his unconscious and his

subsequent

effort to aestheticize the

emerg-

326 CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ing

terror. The narrator's location is

unidentified;

his detached voice

speaks

from a

void, suggesting

his

isolation, deprivation,

and

pos-

sible madness. The

story

he tells alternates between two fictional land-

scapes

- one the

frigid

northern world where

Allert, Peter,

and his wife

Ursula form a

menage

a

trois,

and the other a southern world of sun

and sea where he

journeys

with Ariane and Olaf. Hawkes once

again

uses antithetical

settings,

but unlike the

opposing

islands in Second

Skin,

representative

of Eros and

Thanatos,

these two

landscapes

con-

tain both sex and death and

ultimately

make them

synonymous.

The northern scene that best illustrates Allert's

equation

of sex

and death takes

place

in Peter's sauna. In contrast to the

frigid

air

outside,

the sauna's intense "heat was

high enough

to stimulate

visions,

to

bring

death." When Ursula arouses Allert with her "oral

passion,"

he descends further into "the timeless heat"

(Death 22)

until he fears

death. Later Peter does die in the

sauna,

where the three of them lie

"as if in a

dream,

naked and white and at our ease"

(169).

A corre-

sponding

scene occurs in the southern

hemisphere

when

Allert, Ariane,

and Olaf

go

to an island of nudists. The

intensity

of the island's blind-

ing

sun and the

glaring

white beach

decompose

all colors and make

"the island

landscape

a brilliant

unreality" (102).

So

searing

is the heat

that Allert

suggests

it could "bake alive infant tortoises"

(101);

indeed

it does become

poisonous

to

Olaf,

who shrinks from

dehydration

and

sunburn,

while Allert and Ariane make love on the beach. These lovers

thrive in the island's

searing landscape

of

"unreality"

that is unsuited

to all other life. Reminiscent of the sauna

episode,

this

"frightening

white scene" of

heat, water,

and

sexuality

also has

deathly

undertones

and

suggests

Allert's attraction to

landscapes

of sex and death.

Although

his sea

voyage

takes him from his frozen northern

world,

it

ironically brings

him to an inverted world of

sun, heat,

and ocean

that also denies

regeneration.

Like other

figures

in American romance who

journey

into their

psychic

wilderness in

pursuit

of their

dreams,

Allert also

investigates

the font of his dreams and risks the

dangers

of annihilation. Whereas

Walden, Moby-Dick,

and

Huckleberry

Finn offer a chance of tem-

porary

return to

pastoral simplicity,

Allert remains exiled in his dream-

world.

Psychic

renewal is

possible only

when the exile is

imperma-

nent. Allert remains an aimless traveler who drifts between two worlds.

Unlike

Skipper,

he does not trade one world for another

or,

like

Cyril,

attempt

a

faltering

reconciliation between the two. Hawkes

implies

that Allert's

voyage

has led him not to freedom and a world of total

possibility

but to denial of life. His

pursuit

of his

imagination brings

HAWKES 327

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

destruction. While on board the

ship,

Allert kills Ariane

by dropping

her into the ocean and then kills himself

by remaining

lost in the waters

of his

psyche. Death, Sleep

& the

Traveler, according

to

Hawkes,

"mixes the

night

sea

journey

with a real descent into the realm of

death;

the narrator is accused of murder and suffers his own

psychic

death"

(qtd.

in

Yarborough 73). Allert, nevertheless,

refuses to admit his

culp-

ability.

His final words are "I am not

guilty." Claiming

innocence with

these last

words,

he denies not

only

his

guilt

as a murderer but also

his

guilt

as an artist.

Whereas Allert refuses to admit that his

pursuit

of artistic illu-

sion has

reaped devastation, Papa,

the narrator of

Travesty,

con-

sciously

chooses death over life. He makes death his chosen art form.

Delivering

an

uninterrupted monologue

on the aesthetics of

death,

Papa

careens

through

the

night,

hell-bent on suicide. Hawkes reduces

the novel's

landscape

to the confines of the

car, making

it

synony-

mous with the narrator's

mind;

the ride itself

suggests

another interior

journey

into the

imagination,

like Allert's ocean

voyage.

Yet a differ-

ence remains. Allert floats on his

psychic waters,

and as he heads for

oblivion,

he takes notes.

Papa,

on the other

hand,

is at the

steering

wheel, directing

imminent destruction. Rather than

merely drifting

to inevitable

annihilation, Papa argues

for the conscious

design

of

death,

a

planned execution,

not a "submission to an oblivion"

(Travesty

57).

For him death is an artistic

experience

to be immortalized in the

landscape

of the novel. For him the ultimate artistic

experience

is the

creation of death

- a final union of

paradoxes

where creator and crea-

tion are one. This fatal

design

is the

perfect composition,

a "tableau

of chaos"

(59).

Just as

Skipper

values his

occupation

as artificial

inseminator,

Cyril,

his

tapestry,

and

Allert,

his

dreams, Papa

likewise values arti-

fice over

reality.

When he

rages

toward the final

purity

of

creation,

he

seeks

illusion over the raw material of life. His

pursuit

of death

is, therefore,

not

only

an

imposition

of form on

chaos,

but also a crea-

tion of

something

outside of life: "that

nothing

is more

important

than

the existence of what does not

exist;

that I would rather see two

shadows

flickering

inside the head than all

your flaming

sunrises set

end to end. There

you

have

it,

the

theory

to which I hold as does the

wasp

to his dart"

(57). Although

a comic

exaggeration

of artistic

pur-

suit, Papa's

statement nevertheless

espouses

Hawkes's belief in the

artist's need to

defy

the world around him and "to create from the

imagination

a

totally

new and

necessary

fictional

landscape

or

visionary

world"

("Interview"

with Enck

141).

This dictum is echoed in

Papa's

328 CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

italicized words:

"Imagined life

is more

exhilarating

than remembered

life" (127).

This

belief,

which all Hawkes's narrators

hold, explains

their

monomaniacal insistence on the artistic act that

inevitably

leads them

into their own

psychic

underworlds. Like Narcissus's

plunge

into the

waters of his own

reflection, Papa's

car ride is a

metaphor

for the

absolute artistic

experience.

Hawkes

suggests

that such a romantic

endeavor must be fatal. The

artist-figures

in the triad are victimized

by

their own radical

pursuit

of freedom as it resides in the creative

imagination

and

by

their rebellion

against

life's limitations. The

inherent

irony,

of

course,

is that in

combatting

death

(stasis)

art leads

to the same inevitable result. As

Papa says

in his

closing words,

"there

shall be no survivors. None"

(128). Travesty

thus ends with the final

fictional

landscape-the

destructive

vitality

of man's

psyche.

Because

Travesty presses landscape

to the lowest limits of

psychic

isolation,

some critics

suggest

that Hawkes has nowhere to

go-no

other worlds to

explore.

John

Graham,

for

example, says:

"In

Travesty

the

progression

into an isolated world of

language goes

so far

that,

without a new

start,

Hawkes

may

next offer a blank

page" (49).

The

Passion Artist

(1979)

and

Virginie:

Her Two Lives

(1982)

mark

Hawkes's "new start." Published

by Harper

and

Row,

instead of New

Directions,

and written for a

larger audience,

these two novels are his

most accessible to date. Rather than

reducing

the fictional world to

the confines of his narrator's interior

landscape,

Hawkes

opens up

his last two fictions

by presenting

a character in an external world.

With The Passion Artist Hawkes returns to the

distancing

of a third-

person

narrator and to a

landscape

set in a

European

location.

Although Virginie:

Her Two Lives has a

first-person narrator,

she is

an

eleven-year-old girl

who functions

mainly

as an innocent

companion

to the novel's central

artist-figures, Seigneur

and

Bocage.

Not a direct

participant, Virginie

offers some distance on the

proceedings.

Besides

this

change

in

narrator,

the novel also takes

place

in a

specific

locale

-

Paris and the

countryside

of France. With both these novels Hawkes

returns to

landscapes

tied to verifiable

settings,

as was true of his

early

fiction.

The world

expressed

in The Passion Artist in

many ways

resembles

Hawkes's

early

fictional

landscapes,

but with a difference. In The

Cannibal, The Goose on the Grave, The Owl, and The Lime

Twig,

the violence of

war, the

repression

of social

institutions, and the

sterility

HAWKES 329

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

of sex all combine to

present

a

damning portrait

of the modern world.

The Passion Artist evokes a similar world view. Like

Spitzen-on-the-

Dein,

the

"city

without a name"

(Passion 181)

embodies the

sterility

of modern civilization with its

gray buildings,

desolate

parks,

and

pre-

ponderance

of institutions. Such a

portrait

of

society

is a

given

in

Hawkes's

work,

but his artistic

energy

no

longer

seems

engaged

in con-

veying

this bleak world's

chaos;

his

emphasis

has

changed.

Rather than

offering

surrealistic

descriptions

of a

decomposing world,

as he does

in his

early fiction,

Hawkes

suggests

this town's minimalism in his

prose:

the

city

in which he lived was without

trees,

without national

monuments,

without

ponds

or flower

gardens,

without even a

single building

to attract

visitors from other

parts

of the world. It was a small bleak

city consisting

almost

entirely

of

cheaply

built concrete

dwellings

and unfinished

apartment

houses. It was a

city

without

interest,

without

pride,

without

efficiency. (11)

In this

description

Hawkes's

language

reflects the listlessness of the

static

landscape

instead of

countering

it with a

Dionysian

form of

verbal

energy.

In The Passion Artist Hawkes is not content with

just presenting

landscapes

of

apocalypse

and doom. In a 1979 interview he

implies

that his fictional worlds have

developed. Referring

to the

anonymous

European city

in The Passion

Artist,

he

says,

"We are

archaeologi-

cally

on

top

of the buried

city

of

Spitzen-on-the-Dein,

and

ironically,

the new world is

bleaker,

deader than the world of The Cannibal"

(Radical 185).

In the novel he writes:

Here was the outcome of the centuries of death and

agony;

the

paths

of the

great

minds ended

here;

dreamers of

palaces

and holocausts had invented

nothing.

And what was this

city, denying

in its

daily

life the

validity

of re-

corded

history,

if not the

very

domain of the human

psyche?

The

irony

of

order

existing only

in desolation and discomfort was a satisfaction

beyond

imagining. (11-12)

The human

negation

illustrated

by

the unnamed

city's sterility

is not

tied to war and irrational

violence,

as in the earlier

fiction,

but to the

repression

of the "domain of the

psyche." True,

the conflict between

authoritarian, life-denying

order and creative

irrationality

has

permeated

all of Hawkes's works and been evidenced in the novels'

landscapes.

In the

early

fiction the conflict is characterized

by entropic

landscapes

wrecked

by

war and in the later fiction

by landscapes

more

330 CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

and more disordered

by

the destructiveness of the narrator's own

psyche.

With The Passion

Artist, however,

Hawkes

brings together

these two domains -

by presenting

both a civilization in

collapse

and

an interior excavation into the

psyche.

The Passion Artist focuses on sexual

repression

as the source of

a culture's authoritarianism and man's enslavement to a life bereft of

imagination. Dominating

the entire

city's landscape

is a woman's

prison,

La

Violaine,

a

symbol epitomizing

the sexual

deprivation

of

modern civilization. The incarceration of women characterizes this

society.

Konrad

Vost,

the

middle-aged protagonist, parallels

his

deficient

surroundings

with his

rigid

self-control and sexual

celibacy.

When a

prison

riot at La Violaine breaks

out,

Vost and other male

volunteers enter the

prison

to

quell

the riot but instead

participate

in

it. Hawkes

suggests through

this

eruption

the

dangers

of

confining

not

only unruly sexuality

but also all

disruptive

needs

lodged

in the

unconscious. La

Violaine,

like

Hugh's dungeon,

is emblematic of man's

culturally repressed

unconscious

("the

domain of the

psyche").

Similar

to other

gothic

enclosures that confine

nightmares,

the

prison

embodies

Vost's worst fears as well as his

only

chance of

tapping

life's

mysteries.

At this

point

The Passion Artist is reminiscent of Hawkes's other

post-1964

fiction.

Although

not filtered

through

a

first-person

nar-

rator,

the

landscape

becomes internalized and Hawkes mirrors Vost's

"disordering":

"the

prison

had

exploded,

so to

speak;

interior and

exterior life were

assuming

a

single shape" (74).

His

"disordering"

takes

place

in two locales: inside the

city's prison

itself and in an old stable

in an

outlying

marsh.

Playing

on the

age-old

distinction between the

"city"

and the

"country,"

Hawkes

dichotomizes

the forces of civiliza-

tion and

nature, illustrating

the central conflict between

repressive

con-

sciousness and the

irrational, imaginative

unconscious. The

dichotomy

between

"city"

and

"country"

is also clear in

Virginie:

Her Two

Lives,

with the

presentation

of Paris in 1945 as

opposed

to the rural French

countryside

of 1740. Even

though

a character does not travel from

one

experience

to

another,

in this novel Hawkes

juxtaposes

the

city

and rural

settings

to dramatize the conflict.

Like Allert's

voyage

and

Papa's ride,

Vost's

trip

from

city

to marsh

is a

journey

into the interiors of self. The turn inward is

immediately

characterized

by

the

squalid

nature of the

landscape

itself and

by

the

return of Hawkes's

visionary

use of

language:

off

to his

right lay

a

geometric arrangement

of wet stones where

primitive

buildings, long

since dissolved, had sheltered both men and animals. More

HAWKES

331

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

fence

posts,

the rotten ribs and backbone of a small

boat, brightly

colored

marsh

plants festering

in sockets of

ice,

the

fragments

of a shattered

aque-

duct

gray

and

dripping

where moments before there had been

only

flatness

and

emptiness, abrupt

discolorations that revealed

quicksand

or

underground

rivers: it was all an

agglomeration

of

flashing mirrors,

the

strong

cold

salty

air was

impossibly heavy

with the smell of human excrement and of human

bodies armed and booted and

decomposing

under the

ferns,

behind

piles

of

rocks,

in the

depths

of the wells.

(The

Passion Artist

85)

Like the

entropic decay

of The Cannibal's

landscape,

this marsh

actively decomposes

all

signs

of life and "was in itself a

morgue" (99).

Walking deeper

into its dark

formlessness,

Vost finds a stone enclo-

sure of "wet rocks" and

"slimy roughness."

Womblike in its

warmth,

yet repulsive

in its

filth,

this

obviously

sexual

symbol

is nature's ana-

logue

to civilization's

prison.

A recurrent

symbol

in Hawkes's

fiction,

this chamber of sex and death

subjects

the character to

unexplored

psychic

terrors

(just

as the

lighthouse

does in Second

Skin,

the

dungeon

in The Blood

Oranges,

and the ocean liner in

Death, Sleep

& the

Traveler).

Likewise,

the

entirety

of

Virginie:

Her Two Lives takes

place

in

such

disordering

interiors. The novel alternates between a low-rent

flophouse

in

postwar

Paris and a castle of erotic decadence set in the

French

countryside

of 1740. Within either one of these interiors lies

the

possibility

of the ultimate in both sexual

expression

and

complete

degradation.

In the Paris salon five

trollops

in various

stages

of undress

cavort with a tattooed boxer and an old

man,

under the behest of

Bocage,

a

greasy

cab driver.

Although

the

group

frolics

congenially,

the

atmosphere

is

deathly

because of the mute

presence

of Maman.

Upstairs

the "bedridden

effigy"

of Maman lies

paralyzed

in a

dark,

camphorous

bedroom. In the

countryside

chateau of 1740 five French

beauties live in the

elegant simplicity

of a castle with stone

corridors,

vaulted

windows,

and

courtyards

and in the

pastoral beauty

of

shep-

herds'

huts, haystacks,

and

poplars.

Yet within this rural

tableau,

which

Virginie

describes as "the

very

domain of

my purity" (Virginie 50),

Seigneur

oversees acts of

bestiality

and self-abasement. The

landscapes

themselves,

whether

plebian

or

aristocratic,

as well as the

experiences

within them

suggest paradoxical

extremes

- of terror and freedom

-

and relate to the

epigraph by

Heide

Ziegler: "beauty

is

paradox."

Captives

of these dark

interiors,

Vost and

Virginie,

like all of

Hawkes's

characters,

are

caught

in

nightmares

of sex and violence.

Whether external microcosms of an

entropic

modern world or internal

332 CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

representations

of a narrator's

psyche,

all of Hawkes's

landscapes

imprison

the characters. In The Passion Artist Hawkes externalizes

the

imprisonment

as a

symbol

not

only

of a

repressive

world's con-

finement of the individual

spirit

but also of the individual's enslave-

ment to his own

submerged

unconscious. After

Vost's

journey

into

the

marsh,

it is therefore

fitting

that he is

brought

back to

prison.

His

release, ironically,

comes from

imprisonment. By being

held

cap-

tive in the darkness of his own

interior,

Vost is forced to

experience

the ambivalences

present

in the unconscious - the terror and the

freedom.

For the first time in Hawkes's fiction the

paradoxes

evident in

the

landscape,

to which the main character is

subjected,

are

ultimately

transcended. Not an

artist-figure

like

Skipper

who transforms one

world into

another,

Vost reconciles the ambivalences in his uncon-

scious. Freed from the

imprisonment

of

self,

he achieves the ultimate

artistic

experience through

sex

(not death),

the "willed erotic union"

of the self and the

other,

the creator and the

creation,

and thus achieves

momentarily

what all of Hawkes's

first-person

narrators

try

to create

in their fictional

landscapes.

Unlike

Allert,

who

merely

dreams

it,

or

Papa,

who

aesthetically designs it,

Vost not

only

confronts but attains

the actual

experience.

The

possibility

of

achieving

such freedom exists

in Hawkes's

world,

both in The Passion Artist and

Virginie:

Her Two

Lives. Hawkes

explains

in his interview with Robert Scholes:

my

fiction is

generally

an evocation of the

nightmare

or terroristic universe

in which

sexuality

is

destroyed by law, by dictum, by

human

perversity, by

contraption,

and it is this destruction of human

sexuality

which I have

attempted

to

portray

and confront in order to be true to human fear and

to human

ruthlessness,

but also in

part

to evoke its

opposite,

the moment

of freedom from

constriction, constraint,

death.

("Conversation" 207)

The cost of such freedom is

great.

In Hawkes's world authori-

tarian order and erotic

vitality inevitably

collide in violent

disruption.

Vost is shot as he

emerges

from the

prison gates,

and

Virginie perishes

in flames. On the other side of

completely integrated psychic experi-

ence is annihilation. Thus Vost achieves "his final

irony"

and in death

discovers "for himself what it was to be

nothing" (The

Passion Artist

184). Virginie

also is

destroyed

after

finally consummating

her rela-

tionship

with her creator-father. As the Beckett

epigraph suggests,

"Birth was the death of her." In the Paris

sequence

her Maman sets

fire to their

abode,

and in the other

sequence Virginie joins

her creator

HAWKES

I

333

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(Seigneur) being

burned at the stake. The novel

begins

and ends with

apocalyptic

flames.

Despite

the

paradoxical

extremes

present

in Hawkes's fictional

landscapes, they ultimately

all move toward death - whether it is the

destruction inherent in a

repressive

world or in an irrational mind.

The triad shows the

danger

of

tapping

the

irrational;

The Passion Artist

shows the

danger

of

denying

it.

Believing

in the

necessity

of

pursuing

demons in order to exorcise hidden fears

responsible

for the external

world's

bleakness,

Hawkes follows his characters into their inner

recesses. From these interior

journeys

into man's

psyche

have

emerged

lush

landscapes

of exotic

sexuality

and

lyricism

as well as the

darkest,

most horrific

nightmares imaginable.

These

emerging ambiguities

come

from Hawkes's own

plumbing

of his

unconscious,

from which

spring

his visions. In an

article,

Hawkes writes:

"my

own

imagination

is a

kind of hall of

'whippers'

in which the materials of the unconscious

are

beaten,

transformed into fictional

landscape

itself"

("Opera

and

Skin"

20).

Hawkes

probes

his unconscious not

only

to stimulate his own

artistic visions but also to

express

his belief that from this

pursuit

comes

balance.

Only by excavating

the interior

depths

where the

irrational,

imaginative,

and erotic lie can man ever achieve

harmony.

Not

deny-

ing

the

significance

of

sanity

or

rationalism,

Hawkes

pursues unreason,

which is too often

denied,

in an effort to

forge

a union:

"Yes,

of course

sanity

is

important.

But basic

harmony, serenity,

and a rational

equi-

librium can be achieved

only

out of a

workshop

of the irrational"

("A

Trap" 179).

Always

interested in

pursuing

the

nightmare,

in

assaulting

the con-

ventional

world,

and in

creating

what did not exist

before,

Hawkes

uses the device of fictional

landscape

so

necessary

to his creative vision

as well as his aesthetic.

Explaining

his travels down the dark tunnel

from which

emerge

his

singular

works of

brutality

and

beauty,

he

writes: "For me the writer should

always

serve as his own

angle-

worm

-

and the

sharper

the barb with which he fishes himself out of

the

blackness,

the better"

("Notes" 788).

Hawkes makes no

promises

about what will be retrieved from these

depths,

but the

resulting

land-

scapes testify

to his

unremittingly

creative vision.

University of

Southwestern Louisiana

334

|

CONTEMPORARY LITERATURE

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

WORKS CITED

Graham,

John.

Postscript

to "On The Cannibal." A John Hawkes

Symposium: Design

and Debris. Eds.

Anthony

C. Santore and Michael N.

Pocalyko. Insights

1:

Working Papers

in

Contemporary

Criticism. New York: New

Directions,

1977.

Hawkes,

John. The Blood

Oranges.

New York: New

Directions,

1971.

.-.

The Cannibal. New York: New

Directions,

1949.

.-.

"A Conversation on The Blood

Oranges."

With Robert Scholes. Novel 5

(1972):

197-207.

.-.

Death, Sleep

& the Traveler. New York: New

Directions,

1974.

-.

"John Hawkes: An Interview." With John Enck. Wisconsin Studies in Con-

temporary

Literature 6

(1965):

141-55.

-.

"John Hawkes on His Novels: An Interview with John Graham." Massa-

chusetts Review 7

(1966):

449-61.

.-.

"Notes on the Wild Goose Chase." Massachusetts Review 3

(1962):

784-88.

.-.

"The

Floating Opera

and Second Skin." Mosaic 8

(1974):

17-28.

.-.

The Passion Artist. New York:

Harper

and

Row,

1979.

.-.

The Radical

Imagination

and the Liberal Tradition: Interviews with

English

and American Novelists. Interview with Heide

Ziegler.

Eds. Heide

Ziegler

and

Christopher Bigsby.

London: Junction

Books,

1982. 169-87.

-.

"Interview." With John Kuehl. Kuehl 155-83.

.-.

Second Skin. New York: New

Directions,

1964.

.-.

"A

Trap

to Catch Little Birds With." Interview with

Anthony

C. Santore

and Michael

Pocalyko.

A John Hawkes

Symposium: Design

and Debris. Eds.

Anthony

C. Santore and Michael

Pocalyko. Insights

1:

Working Papers

in Con-

temporary

Criticism. New York: New

Directions,

1977. 165-84.

.-.

Travesty.

New York: New

Directions,

1976.

"-.

Virginie:

Her Two Lives. New York:

Harper

and

Row,

1982.

Hawkes, John,

and John Barth. "Hawkes and Barth Talk About Fiction." Ed. Thomas

LeClair. The New York Times Book Review

1 April

1979:

7,

31-33.

Kuehl,

John. John Hawkes and the

Craft of Conflict.

New

Brunswick,

N.J.:

Rutgers

UP,

1975.

Lentricchia,

Frank. Robert Frost: Modern Poetics and the

Landscapes of Self.

Durham,

N.C.: Duke

UP,

1975.

Marx,

Leo. The Machine in the Garden:

Technology

and the Pastoral Ideal in America.

New York: Oxford

UP,

1964.

Olderman, Raymond

M.

Beyond

the Waste

Land:

A

Study of

the American Novel

in the Nineteen-Sixties. New Haven: Yale

UP,

1972.

Tanner, Tony. City of

Words: American Fiction 1950-1970. New York:

Harper

and

Row,

1971.

Yarborough,

Richard. "Hawkes' Second Skin." Mosaic 8

(1974):

65-75.

HAWKES 335

This content downloaded from 197.1.230.138 on Sun, 13 Apr 2014 10:22:39 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Noys and Murphy - IntroDokument18 SeitenNoys and Murphy - Introblackpetal1100% (1)

- Science Fiction, New Space Opera, and Neoliberal Globalism: Nostalgia for InfinityVon EverandScience Fiction, New Space Opera, and Neoliberal Globalism: Nostalgia for InfinityBewertung: 3 von 5 Sternen3/5 (2)

- The Time Machine As A Dystopian FictionDokument20 SeitenThe Time Machine As A Dystopian FictionNazish BanoNoch keine Bewertungen

- SARA MARTIN Iain M. Banks Hydrogen Sonata Scottish IndependenceDokument18 SeitenSARA MARTIN Iain M. Banks Hydrogen Sonata Scottish Independenceyoyoyo yoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ionescos Rhinoceros and The Menippean TraditionDokument15 SeitenIonescos Rhinoceros and The Menippean TraditionAndreea JosefinNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parody IslandDokument8 SeitenParody IslandRaul A. BurneoNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Orientalist Semiotics of »Dune«: Religious and Historical References within Frank Herbert's UniverseVon EverandThe Orientalist Semiotics of »Dune«: Religious and Historical References within Frank Herbert's UniverseNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Capitol of Darknesse Gothic Spatialities in The London of Peter Ackroyd's HawksmoorDokument23 SeitenThe Capitol of Darknesse Gothic Spatialities in The London of Peter Ackroyd's Hawksmoorfahime_shNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philip Roth's Rude Truth: The Art of ImmaturityVon EverandPhilip Roth's Rude Truth: The Art of ImmaturityBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2)

- FRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFDokument16 SeitenFRIEDMAN, M. Samuel Beckett and The Nouveau Roman PDFyagogierlini2167Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Play of Space: Spatial Transformation in Greek TragedyVon EverandThe Play of Space: Spatial Transformation in Greek TragedyNoch keine Bewertungen

- 183 Good LadDokument19 Seiten183 Good LadYago GierliniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Haunted historiographies: The rhetoric of ideology in postcolonial Irish fictionVon EverandHaunted historiographies: The rhetoric of ideology in postcolonial Irish fictionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pilhuj, "THE SCENE MOSCO": CREATING EASTERN EUROPE FOR EARLY MODERN ENGLISH AUDIENCES IN JOHN FLETCHER'S THE LOYAL SUBJECT (1618)Dokument17 SeitenPilhuj, "THE SCENE MOSCO": CREATING EASTERN EUROPE FOR EARLY MODERN ENGLISH AUDIENCES IN JOHN FLETCHER'S THE LOYAL SUBJECT (1618)Paul WorleyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chris Worth, Ivanhoe and The Making of Britain (1995)Dokument14 SeitenChris Worth, Ivanhoe and The Making of Britain (1995)HugociceronNoch keine Bewertungen