Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Antipsychotics Presentation

Hochgeladen von

api-258330934Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Antipsychotics Presentation

Hochgeladen von

api-258330934Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

BY AMY, ANDRE A & S T E PHANI E

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

INTRODUCTION

What are antipsychotics?

Timeline

Mechanism of Action

The Fast Off Theory

Applications

Pediatric use

Off-label uses

Listing

Side effects

Withdrawal effects

Controversies

ANTIPSYCHOTICS

Also known as neuroleptics or major tranquilizers

Early antipsychotics are now called typical or first

generation (1960s) and newer antipsychotics are

called atypical or second generation (1990s)

Use of typicals has significantly decreased since the

advent of atypical antipsychotics

Atypicals thought to have fewer/less severe side effects

TIMELINE

Prior to 1950s treatment for schizophrenia and psychosis included:

Electroconvulsive therapy

Prefrontal lobotomy

Confinement to large institutions (non-specific sedation

and restraint for agitation)

1950: Chlorpromazine

First synthesized for use in anesthesia

Noticed it produced a calming effect and reduced

episodes of aggression in patients with schizophrenia

Was most popular throughout 1960s and 1970s

Not effective in dull, apathetic, deteriorated schizophrenic patients

Associated with Parkinson-like side effects

1958: Clozapine synthesized in Bern, Switzerland

Effective antipsychotic and not associated with extrapyramidal symptoms

Also ameliorates negative symptoms of schizophrenia

Only approved by the FDA in 1990 due to concerns it caused a potentially fatal side effect

involving reduced white blood cell counts

No longer first-line treatment but when others fail

TIMELINE CONT

1994: Risperidone approved by the FDA

Approved for childhood disorders and as result one of

most frequently prescribed

1996: Olanzapine approved by the FDA

1997: Quetiapine approved by the FDA

2001: Ziprasidone approved by the FDA

2009: Asenapine approved by the FDA

2009: Iloperidone approved by the FDA

2010: Lurasidone approved by the FDA

2013: Aripiprazole approved by the FDA

MECHANISM OF ACTION

All antipsychotics work as antagonists of dopamine D2 receptors

Typical Antipsychotics

Level of D2 blockade is directly related to antipsychotic effect (optimal

occupancy between 60%-70%)

Also act on other neurotransmitter systems besides dopamine:

Cholinergic muscarinic and alpha-1-adrenergic receptors

Atypical Antipsychotics

Also block serotonin (5-HT2A)

receptors

This regulates dopamine release in

pituitary, striatal and neocortical

regions of brain

Counteracts depletion of dopamine in areas of brain

that cause adverse effects

THE FAST OFF THEORY

Both typical and atypical antipsychotics attach to D2 receptors

Differ in how fast and how frequently they come off and on of

receptors

Atypicalsdissociate quickly from receptors

This allows endogenous dopamine to bind to same receptors

Explains how atypicals treat psychosis without extrapyramidal

symptoms

APPLICATIONS

Officially approved only for treatment of

Schizophrenia

Schizoaffective Disorder

Psychosis (including delusions and hallucinations)

Bipolar Affective Disorder (recently)

Bipolar Depression

Bipolar Mania

Used to treat both

Positive symptoms

Hallucinations, delusions

Negative Symptoms

Apathy, anhedonia, blunted cognition

PEDIATRIC USE

Generally not recommended for use in children

2006 none approved for children but prescribing for

behavioural disorders was common

Recently, quetiapine and risperidone approved

Risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine and

aripiprazole are now indicated as useful for

treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar 1

manic/mixed episodes

For many disorders, symptoms must be severe or

other treatments failed to work

Two antipsychotics should never be used in the

same person

OFF-LABEL USES

Obsessive Compulsive Disorder

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

Tourette Syndrome (Tics)

Autism and PDD

Aggression, irritability, impulsivity, repetitive & self-injurious

behaviour

Borderline Personality Disorder

Insomnia

Dementia

Aggressiveness

Major Depressive Disorder

Generalized Anxiety Disorder

TYPICAL/FIRST GENERATION

Haloperidol

Chlorpromazine

Loxapine

Perphenazine

Pimozide

Prochlorperazine

Promazine

Trifluoperazine

(no longer commonly prescribed)

ATYPICAL/SECOND GENERATION

Aripiprazole

Asenapine

Clozapine

Iloperidone

Lurasidone

Olanzapine

Palperidone

Quetiapine

Risperidone

Ziprasidone

SIDE EFFECTS

One of the primary reasons why people stop

taking antipsychotics is due in part to the adverse

effects

Common 1-50% incidence for

most antipsychotic drugs

include:

Weight gain

Sedation

Headaches

Dizziness

Diarrhea

Anxiety

Orthostatic Hypotension

SIDE EFFECTS

Adverse Effects continued . . .

Extrapyramidal side effects

- Akathisia - Parkinsonism

- Dystonia - Tremor

Hyperprolactinaemia

- Galactorrhoea - Sexual Dysfunction (in both sexes)

- Gynaecomastia - Osteoporosis

Anticholinergic side effects

- Amnesia - Constipation

- Blurrred vision - Dry mouth (also hyper salivation)

- Reduced perspiration

Tardive Dyskinesia

SIDE EFFECTS

Rare/Uncommon (<1% incidence for most antipsychotic drugs)

Metabolic problems (Type II Diabetes)

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome

Pancreatitis

Seizures

Myocardial infarction

Stroke

*Some studies have found decreased life expectancies associated with

the use of antipsychotics. Also increases the risk of early death in

individuals with dementia

*Chronic treatment with antipsychotics may reduce amounts of brain

tissue and potentially cause some of the symptoms believed to be due

to schizophrenia

SIDE EFFECTS

There have been 117,414 Adverse Drug Reactions in connection with

antipsychotics that have been reported to the FDAs Adverse Event

Reporting System (MedWatch), between 2004 and 2012.

The FDA estimates

that less than 1% of

all serious events are

ever reported to it,

so the actual

number of side

effects occurring

are most certainly

higher.

WITHDRAWAL EFFECTS

Physical dependence can result in withdrawal

effects especially on abrupt discontinuation of

the antipsychotic after prolonged use

Factors which increase effects: length, dose,

speed of cessation

During withdrawal recurrence of psychotic

symptoms may occur, can be confused with a

relapse

WITHDRAWAL EFFECTS

Most withdrawal effects are relatively mild and resolve

spontaneously

Withdrawal of an antipsychotic after long-term therapy

should be gradual and closely monitored to avoid the

risk of acute withdrawal syndromes or relapse

CONTROVERSIES

Dementia

90% of people with dementia

exhibit aggression, agitation, loss

of inhibitions and psychosis

(delusions and hallucinations).

Drugs used can make patients

calmer and more compliant

2/3 of these of these prescriptions

are inappropriate.

Johnson & Johnson allegedly payed kickbacks to

Omnicare to promote Risperidone in nursing homes

CONTROVERSIES

Medicating the Young

Second-generation antipsychotics, or SGAs, are being

prescribed to two- and three-year-olds for aggression,

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorders,

frustration intolerance and even poor sleep.

Elevated blood fats and abnormal blood sugar levels

Across Canada, from 2005 to 2009,

antipsychotic drug prescriptions

for children and youth increased

114 per cent.

Prescribing is being done not by

psychiatrists, but by family

doctors, often with little training

CONTROVERSIES

Drug Studies

In 54% of studies, duration was less that 6 weeks

Mean number of patients was 65

Only 41% showed therapeutic response to medication,

compared to 24% on placebo

Evidence flawed as they didnt take into account that meds

sensitize the brain and provoke psychosis if discontinued

Not approved for pediatric pops.

The constantly poor quality of reporting

is likely to have resulted in an

overoptimistic estimation of the effects

of treatment.

CONTROVERSIES

Pharmaceutical Companies

For example, Johnson & Johnson has agreed to pay $2.2

billion misbranded the atypical antipsychotic drug Risperdal

for uses not approved as safe and effective by the Food and

Drug Administration

Company combined negative data with other studies to

make it appear that there was an overall lower risk for adverse

events.

Antipsychotic drugs are now the

top-selling class of pharmaceuticals in

America

Every major company selling the drugs have been involved in

legal claims involving including Medicare fraud, off label

promotion, and inadequate manufacturing practices.

REFERENCES

Antipsychotics learning module. (n.d.). Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency.

Retrieved March 4, 2014, from ww.mhra.gov.uk/ConferencesLearningCentre/

LearningCentre/Medicineslearningmodules/Reducingmedicinerisk/

Antipsychoticslearningmodule/CON155606?useSecondary=&showpage=30

Bellack AS (July 2006) Scientific and Consumer Models of Recovery in Schizophrenia:

Concordance, Contrasts, and Implications. Schizophrenia Bulletin 32 (3): 43242. doi:

10.1093/schbul/sbj044. PMC 2632241. PMID 16461575

Caccia, S., Clavenna, A. & Bonati, M. (2011). Antipsychotic drug toxicology in children. Expert

Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology, 7, 591-608. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.562198

Carpenter, W. T. Jr., & Davis, J. M. (2012). Another view of the history of antipsychotic drug

discovery and development. Molecular Psychiatry, 17, 1168-1173.

Howard, P., Twycross, R., Shuster, J., Mihalyo, M. & Wilcock, A. (2011). Antipsychotics. Journal of

Pain and Symptom Management, 41, 956-965. doi:

http://dx.doi.org.ezproxy .lib.ucalgary.ca/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.002

Kirkey, S. (2013, May 20). Dramatic growth in antipsychotic drug use even targets infants, experts

say. Canada.com. Retrieved March 4, 2013, fromwww.canada.com/health/Dramatic+

growth+antipsychotic+drug+even+targets+infants+experts/8407086/story.html

McKean, A. & Monasterio, E. (2012). Off-label use of atypical antipsychotics: Cause for concern?

CNS Drugs, 26, 383-390. doi: 10.2165/11632030-000000000-00000

Meyer, J. M., & Simpson, G. M. (1997). From Chlorpromazine to Olanzapine: a brief history of

antipsychotics. Psychiatric Services, 48(9), 1137-1139.

REFERENCES

Muench, J., & Hamer, A. M. (2010). Adverse effects of antipsychotic medications.

Am Fam Physician, 81(5), 617-22.

Shen, W. W. (1999). A history of antipsychotic drug development. Comprehensive

Psychiatry, 40(6), 407-414.

Schwartz, T. & Stahl, S. (2011). Treatment strategies for dosing the second

generation antipsychotics. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 17, 110-117.

doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00234.x

Shih, D. (2007). Medication overview: Common psychotropic medications used in

psychiatric disorders of children and adolescents. Healthy Minds/Healthy Children.

Steele, D., & Keltner, N. L. (2013) Overview of psychoparmacology. In K. R. Tusaie & J. J.

Fitzpatrick (Eds.), Advanced practice psychiatric nursing: integrating

psychotherapy, psychopharmacology, and alternative/complementary approaches

(pp. 55-77). New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

Stip, E. (2000). Novel antipsychotics: issues and controversies. Typicality of atypical

antipsychotics. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience, 25(2), 137.

Watts, V. (2013, December 4). PDrug Firm Pays Billions for Misbranding Antipsychotics.

PsychiatryOnline | Psychiatric News | News Article. Retrieved March 4, 2014, from

http://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/newsarticleaspx?articleid=1788265

Zuckerman, E. & Kaden, P. (2013). Checklist of dosages and uses of 100 common

psychotropic medications by generic name. www.CliniciansToolBox.com

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- Social Media-2Dokument10 SeitenSocial Media-2api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fasdfinalworkingdocument1 2Dokument42 SeitenFasdfinalworkingdocument1 2api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio CVDokument3 SeitenPortfolio CVapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stephanie Janzen - Best PracticesDokument11 SeitenStephanie Janzen - Best Practicesapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Fiona Portfolio ReportDokument4 SeitenFiona Portfolio Reportapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Debate AnalysisDokument7 SeitenDebate Analysisapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Reading Comprehension Intervention StrategiesDokument18 SeitenReading Comprehension Intervention Strategiesapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- PPVT 4Dokument13 SeitenPPVT 4api-258330934100% (1)

- Personal Position PaperDokument18 SeitenPersonal Position Paperapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Article Critique Edps 612 l01Dokument8 SeitenArticle Critique Edps 612 l01api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- First Step To SuccessDokument20 SeitenFirst Step To Successapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Janzen Stephanie - Article Critique Edps 612 03 Docx0-2Dokument8 SeitenJanzen Stephanie - Article Critique Edps 612 03 Docx0-2api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ecological Article CritiqueDokument7 SeitenEcological Article Critiqueapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Janzen - 674 Asynch Activity Week 10Dokument3 SeitenJanzen - 674 Asynch Activity Week 10api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Adhd and Ritalin PaperDokument18 SeitenAdhd and Ritalin Paperapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Jordan PPDokument8 SeitenJordan PPapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- BSP Evaluation PlanDokument3 SeitenBSP Evaluation Planapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Ethical OrganizationDokument11 SeitenEthical Organizationapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- WM MathDokument6 SeitenWM Mathapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Janzen - Edps 674 FbaDokument11 SeitenJanzen - Edps 674 Fbaapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Cultural BiasDokument6 SeitenCultural Biasapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Stephaniejanzen15 11 2012Dokument13 SeitenStephaniejanzen15 11 2012api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Shifting Paradigms in The History of Special EducationDokument10 SeitenShifting Paradigms in The History of Special Educationapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Portfolio Same Report - Jordan Academic PracticumDokument5 SeitenPortfolio Same Report - Jordan Academic Practicumapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Anti Bullying 2Dokument31 SeitenAnti Bullying 2api-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assessment ReviewDokument4 SeitenAssessment Reviewapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Processing Speed HandoutDokument1 SeiteProcessing Speed Handoutapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- Social Skills Rating SystemDokument12 SeitenSocial Skills Rating Systemapi-25833093460% (5)

- Unit PresentationDokument24 SeitenUnit Presentationapi-258330934Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Vibrant Blue Beginner Guide To Essential OilsDokument11 SeitenVibrant Blue Beginner Guide To Essential OilsTonnie RostelliNoch keine Bewertungen

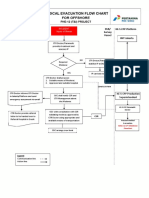

- 3-A4 - Medical Evacuation Flow Chart (Rev.0)Dokument1 Seite3-A4 - Medical Evacuation Flow Chart (Rev.0)SiskaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Covid Hospitals Yet To Get NOC From Fire Department: 20 Critically Ill Die Due To Lack of Oxygen in DelhiDokument16 SeitenCovid Hospitals Yet To Get NOC From Fire Department: 20 Critically Ill Die Due To Lack of Oxygen in DelhiblessNoch keine Bewertungen

- PsychopathiaDokument26 SeitenPsychopathiaKunal KejriwalNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Addiction Casebook - Chap 04Dokument11 SeitenThe Addiction Casebook - Chap 04Glaucia MarollaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Call The MidwifeDokument12 SeitenCall The MidwifeCecilia DemergassoNoch keine Bewertungen

- United States Food and Drug Administration (Usfda)Dokument50 SeitenUnited States Food and Drug Administration (Usfda)Hyma RamakrishnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- EUA Abiomed ImpellaLV IFU3Dokument254 SeitenEUA Abiomed ImpellaLV IFU3Angelina LeungNoch keine Bewertungen

- YMAA - List of Articles About Qigong & MeditationDokument7 SeitenYMAA - List of Articles About Qigong & MeditationnqngestionNoch keine Bewertungen

- Introduction To Clinical AssessmentDokument13 SeitenIntroduction To Clinical AssessmentnurmeenNoch keine Bewertungen

- HeelDokument4 SeitenHeelDoha EbedNoch keine Bewertungen

- Endoscopic Evaluation of Post-Fundoplication Anatomy: Esophagus (J Clarke and N Ahuja, Section Editors)Dokument8 SeitenEndoscopic Evaluation of Post-Fundoplication Anatomy: Esophagus (J Clarke and N Ahuja, Section Editors)Josseph EscobarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complete Project PDFDokument67 SeitenComplete Project PDFRaghu Nadh100% (1)

- Kapitel 6Dokument125 SeitenKapitel 6Jai Murugesh100% (1)

- Fibromyalgia Acupressure TherapyDokument3 SeitenFibromyalgia Acupressure TherapyactoolNoch keine Bewertungen

- Family-Fasciolidae Genus: Fasciola: F. Hepatica, F. GiganticaDokument3 SeitenFamily-Fasciolidae Genus: Fasciola: F. Hepatica, F. GiganticaSumit Sharma PoudelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Social and Emotional Well Being Framework 2004-2009Dokument79 SeitenSocial and Emotional Well Being Framework 2004-2009MikeJacksonNoch keine Bewertungen

- A Fluids and ElectrolytesDokument8 SeitenA Fluids and ElectrolytesAnastasiafynnNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lasers: Effect of Laser Therapy On Chronic Osteoarthritis of The Knee in Older SubjectsDokument8 SeitenLasers: Effect of Laser Therapy On Chronic Osteoarthritis of The Knee in Older SubjectsBasith HalimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Faml360 - Final Assesment PaperDokument9 SeitenFaml360 - Final Assesment Paperapi-544647299Noch keine Bewertungen

- Individual Assignment A1 Engineering Technologist in Society Clb40002Dokument13 SeitenIndividual Assignment A1 Engineering Technologist in Society Clb40002Anonymous T7vjZG4otNoch keine Bewertungen

- Complicatii Si Sechele Tardive Dupa Tratamentul Multimodal Al GlioamelorDokument35 SeitenComplicatii Si Sechele Tardive Dupa Tratamentul Multimodal Al GlioamelorBiblioteca CSNTNoch keine Bewertungen

- Neurologic Music Therapy Improves Executive Function and Emotional Adjustment in Traumatic Brain Injury RehabilitationDokument11 SeitenNeurologic Music Therapy Improves Executive Function and Emotional Adjustment in Traumatic Brain Injury RehabilitationTlaloc GonzalezNoch keine Bewertungen

- GI PathologyDokument22 SeitenGI Pathologyzeroun24100% (5)

- Cholesteatoma Guide: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment OptionsDokument9 SeitenCholesteatoma Guide: Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment Optionssergeantchai068Noch keine Bewertungen

- Potts DiseaseDokument8 SeitenPotts Diseaseaimeeros0% (2)

- AP2 Lab Report Lab 06Dokument4 SeitenAP2 Lab Report Lab 06kingcon420Noch keine Bewertungen

- Orange Peel MSDSDokument4 SeitenOrange Peel MSDSarvind kaushikNoch keine Bewertungen

- Q A Random - 16Dokument8 SeitenQ A Random - 16ja100% (1)

- NMC Standards For Competence For Registered NursesDokument21 SeitenNMC Standards For Competence For Registered NursesAgnieszka WaligóraNoch keine Bewertungen