Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Tracheostomy PDF

Hochgeladen von

Veronica Gatica0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

262 Ansichten8 SeitenTracheostomy is done for airway obstruction, respiratory support, pulmonary hygiene, elimination of dead space, and treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. A chest x-ray will alert the surgeon to tracheal deviation due to cervical and mediastinal tumours, or traction on the trachea due to fibrosis. If airway obstruction is as a consequence of laryngeal cancer, then one should

Originalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

TRACHEOSTOMY.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

PDF, TXT oder online auf Scribd lesen

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenTracheostomy is done for airway obstruction, respiratory support, pulmonary hygiene, elimination of dead space, and treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. A chest x-ray will alert the surgeon to tracheal deviation due to cervical and mediastinal tumours, or traction on the trachea due to fibrosis. If airway obstruction is as a consequence of laryngeal cancer, then one should

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

0 Bewertungen0% fanden dieses Dokument nützlich (0 Abstimmungen)

262 Ansichten8 SeitenTracheostomy PDF

Hochgeladen von

Veronica GaticaTracheostomy is done for airway obstruction, respiratory support, pulmonary hygiene, elimination of dead space, and treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. A chest x-ray will alert the surgeon to tracheal deviation due to cervical and mediastinal tumours, or traction on the trachea due to fibrosis. If airway obstruction is as a consequence of laryngeal cancer, then one should

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Verfügbare Formate

Als PDF, TXT herunterladen oder online auf Scribd lesen

Sie sind auf Seite 1von 8

OPEN ACCESS ATLAS OF OTOLARYNGOLOGY, HEAD &

NECK OPERATIVE SURGERY

TRACHEOSTOMY Johan Fagan

Tracheostomy refers to the creation of a

communication between the trachea and

the overlying skin. This may be done either

by open or percutaneous technique. This

chapter will focus on the open surgical

technique in the adult patient.

I ndications

Tracheostomy is done for airway

obstruction, respiratory support (assisted

ventilation), pulmonary hygiene, elimina-

tion of dead space, and treatment of

obstructive sleep apnoea.

Preoperative evaluation

Level of obstruction: A standard

tracheostomy will not bypass obstruction

in the distal trachea or bronchial tree

Anatomy of the neck: The surgeon should

anticipate a difficult tracheostomy in

patients with short necks, thick necks, and

necks that cannot be extended due to e.g.

rheumatoid or osteoarthritis of the cervical

spine

Deviation of cervical trachea: A chest X-

ray will alert the surgeon to tracheal

deviation due to cervical and mediastinal

tumours, or traction on the trachea due to

fibrosis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Tracheal deviation due to

tuberculosis

Coagulopathy: A coagulopathy should be

corrected prior to surgery. If not

completely corrected, then have

electrocoagulation available at surgery to

aid haemostasis

Cardiorespiratory status: Patients with

upper airway obstruction may have cor

pulmonale, or respiratory acidosis. Some

patients may be dependent on

physiological PEEP to maintain O

2

saturation, or an elevated pCO

2

to maintain

respiratory drive; relieving upper airway

obstruction with a tracheostomy may

paradoxically cause such patients to stop

breathing and become hypoxic.

Laryngeal cancer: If airway obstruction is

as a consequence of laryngeal cancer, then

one should attempt not to enter the tumour

during tracheostomy. This may require a

lower tracheostomy if tumour involves the

cervical trachea. It is prudent to send a

sample from the tracheal window for

histological examination as involvement

by tumour might be useful information for

the surgeon subsequently doing the

laryngectomy.

Tracheostomy procedure

A tracheostomy is best done in the

operating room with good lighting,

instrumentation, suction, and assistance.

Patients may cough on inserting the

tracheostomy tube; hence eye protection is

recommended to prevent transmission of

infections such as HIV and hepatitis.

Anaesthesia: Unless the patient can safely

be intubated or the patient be ventilated

with a mask, a tracheostomy should be

done under local anaesthesia. If there is

concern about the anaesthetists ability to

maintain an airway, then the surgeon

should be present during induction; the

2

skin, soft tissue and trachea (into the

lumen) should be infiltrated with local

anaesthesia with adrenaline before

induction; and a set of tracheostomy

instruments should be set out before

induction of anaesthesia so that an

emergency tracheostomy can be done if

required.

Positioning and draping: The patient is

placed in a supine position with neck

extended by a pillow or sandbag placed

under the shoulders in order to deliver the

trachea out of the thorax and to give the

surgeon adequate access to the cervical

trachea. Such extension may not be

possible in patients with neck injuries, or

rheumatoid and osteoarthritis of the

cervical spine. Some patients with

impending airway obstruction may not

tolerate a recumbent position; the

tracheotomy may then be done with the

patient in a sitting position with neck

extended. The skin of the anterior neck and

chest is sterilised and the neck draped. If

the tracheostomy is being done under local

anaesthesia, the face should not be

covered.

Surface landmarks: The tracheostomy is

created below the 1

st

tracheal ring, so as to

avoid subglottic stenosis as a result of

scarring. Therefore palpating to determine

the location of the cricoid cartilage is

important. When you run your fingers up

the midline of the neck starting inferiorly

at the sternal notch, you 1

st

encounter

prominence of the thyroid isthmus,

followed by the cricoid.

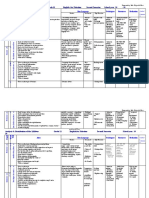

Minimum instruments: A minimum set of

instruments is demonstrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Minimum set of instruments

Skin incision: A horizontal incision is

made one fingerbreadth below the cricoid

prominence. This is cosmetically

preferable to a vertical midline incision.

The incision is carried through the skin and

the subcutaneous tissue. Note that the

platysma is generally absent in the midline.

Take care not to transect the anterior

jugular veins, which are just superficial to

the strap muscles within the investing

cervical fascia, and can be preserved and

retracted laterally (Figure 3). The

remainder of the dissection should remain

strictly in the midline in a vertical plane

to avoid injury to the inferior thyroid veins.

Figure 3: Exposure of anterior jugular

veins and cervical fascia

3

Infrahyoid strap muscles: Figure 4

illustrates the infrahyoid strap muscles.

Figure 4: Infrahyoid strap muscles

Identify the midline cervical fascial plane

between the sternohyoid muscles. Divide

this intermuscular plane by spreading with

a pair of scissors. Repeat this manoeuvre to

separate the sternothyroid muscles, and

retract the muscles laterally (Figure 5).

The trachea and cricoid can now be

palpated.

Figure 5: Retracting sternohyoid and

sternothyroid muscles to expose the

thyroid gland

Thyroid isthmus: The thyroid isthmus

overlies the 2

nd

/3

rd

tracheal rings. The

isthmus should be retracted superiorly to

expose the trachea (Figure 6). Only very

rarely does the thyroid isthmus need to be

doubly clamped, divided, and (suture)

ligated.

Figure 6: Thyroid retracted superiorly and

an inferiorly based flap cut (along red

lines) in anterior tracheal wall

Expose trachea: The infrathyroid trachea

is exposed anteriorly by carefully parting

overlying soft tissues with a pair of

scissors, taking care not to tear the inferior

thyroid veins. Ensure that the surgical field

is dry before proceeding, as it is difficult to

achieve haemostasis once the tracheostomy

tube has been inserted. Should there be

doubt about the location of the trachea, or

there be concern it being confused with the

carotid artery, aspirating air with a needle

attached to a syringe will confirm its

location.

Create tracheostoma: In the wake patient,

lignocaine may again be injected into

tracheal lumen prior to incising the trachea

and inserting the tube in order to reduce

coughing. Upward traction may be applied

to a tracheal hook inserted under a tracheal

ring to stabilise the trachea and deliver it

from the chest. The safest means to create

a tracheostomy in adults is by creating an

inferiorly based flap raised from the

anterior wall of the 3

rd

and 4

th

tracheal

rings. A silk traction suture is passed

through this anterior tracheal flap and

loosely secured to the skin (Figure 7).

Traction on the suture facilitates

reinsertion of the tracheostomy tube in

case of accidental decannulation.

Thyroid cartilage

Cricoid cartilage

Thyroid gland

Sternohyoid muscle

Sternothyroid muscle

4

Alternately one may remove an anterior

cartilage segment of the 2

nd

, 3

rd

or 4

th

tracheal rings.

Figure 7: Flap reflected inferiorly with

traction suture attached to flap

Insertion of tracheostomy tube: The

surgeon assesses the size of the trachea,

and selects the largest sized cuffed

tracheostomy tube that will comfortably fit

the tracheal lumen. Inject air into the

tracheostomy inflatable cuff to test the

integrity of the cuff. Insert the introducer

into the tracheostomy tube. If the patient

has been intubated, the anaesthetist is

asked to slowly withdraw the endotracheal

tube, so that the tracheostomy tube can be

inserted under direct vision. Advance the

tube into the trachea while applying

traction to the silk traction suture attached

to the tracheal flap. Ensure that the tube

has been inserted into the tracheal lumen,

and not a false passage in the paratracheal

soft tissues. Inflate the cuff, attach the

anaesthetic tubing, and hand-ventilate until

one has confirmed correct placement of the

tube within the trachea (Figure 8). Do not

suture the skin tightly around the

tracheostomy tube, as this can promote

surgical emphysema.

Securing the tracheostomy tube: Tapes are

threaded through the holes in the flanges of

the tracheostomy tube, passed around the

neck, and tied, with the neck flexed. If the

ties are placed with the neck extended,

they are too loose when the patient flexes

the neck.

Epiglottis

Glottis

Thyroid cartilage

Cricoid

Thyroid gland

Innominate artery

Sternum

Figure 8: Position of tracheostomy tube

The ties should be tight enough to admit no

more than a single finger under the tape

(Figure 9).

Figure 9: Tracheostomy tube secured with

Velcro tape

It is prudent to suture the tracheotomy tube

to the skin for the first few days to allow

maturation of the tracheocutaneous tract.

The sutures can then be removed and

traditional tracheotomy tapes can then be

used. Following free microvascular

transfer flap reconstruction, tracheostomy

tapes should be avoided; the tracheostomy

should preferably be sutured to the

suprastomal skin, as tracheal tapes may

cause jugular vein compression,

thrombosis, and venous outflow

obstruction and flap failure.

Back wall of trachea

Inferiorly based tracheal

flap

Traction suture

anchoring flap

5

Pitfalls

High tracheostomy: It is important not to

place the tracheotomy above the 2

nd

tracheal ring, as inflammation may cause

subglottic oedema, chondritis of the cricoid

cartilage, and subglottic stenosis.

Low tracheostomy: A tracheotomy should

not be placed below the 4

th

tracheal ring

as:

The distance between the skin and the

trachea increases inferiorly, which

makes tracheal intubation more

difficult

A low tracheostomy may compress and

erode the innominate artery which

passes between the manubrium sterni

and the trachea (Figure 8). This may

cause innominate artery erosion and

fatal haemorrhage. This may be

preceded by a so-called sentinel

bleed

Paratracheal false tract: Inadvertent

extratracheal placement of the

tracheostomy tube can be fatal. It is

recognised by the absence of breath sounds

on auscultation of the lungs, high

ventilatory pressures, failure to ventilate

the lungs, hypoxia, absence of expired

CO

2

, surgical emphysema, and an inability

to pass a suction catheter down the

bronchial tree, and on chest X-ray.

Surgical emphysema, pneumomediastinum,

and pneumothorax: Injury to the pleural

domes is more likely to occur in children,

struggling patients and patients on positive

pressure ventilation. It can be complicated

by a tension pneumothorax. Hence

auscultation of the chest and a CXR should

be performed after tracheostomy,

especially in ventilated patients. Surgical

emphysema may also be promoted by

suturing the tracheostomy wound around

the tracheostomy tube.

Airway fire: Do not enter the trachea with

diathermy, as this may cause an airway fire

in a patient being ventilated with a high

concentration of oxygen.

Choice of Tracheostomy Tube

A variety of tube designs and materials are

available. The choice of tube should

conform to the indication for which it is to

be used. All tubes should have an inner

cannula; this can safely be removed and

cleaned without a need to remove the outer

cannula and hence endanger the airway.

The following factors may influence the

choice of tube:

Tube diameter: Because airway resistance

is related to the 4

th

power of the radius

with laminar flow, and the 5

th

power of the

radius with turbulent flow, it is important

to select a tube that that fits the trachea

snugly. A range of sizes should be

available. It also underscores the

importance of keeping the tube clean, as

accumulation of mucus increases airway

resistance not only by reducing the

diameter, but also by causing turbulent air

flow.

Tracheal seal: A cuffed, plastic

tracheostomy tube is used to create a seal

with the trachea in patients on positive

pressure ventilation, and with fresh

tracheostomy wounds (Figure 10) to

prevent saliva or blood entering the lower

airways. The cuffed tube may be replaced

with an uncuffed tube, either plastic or

metal (Figure 11) in patients who do not

require positive pressure ventilation once

the tract between the skin and the trachea

has become well defined by granulation

tissue at 48hrs, and tracheostomal bleeding

has settled.

6

Figure 10: Plastic low pressure cuffed

tracheostomy tube with outer cannula,

inner cannula and introducer (L to R)

Figure 11: Metal tracheostomy tube with

outer cannula, inner cannula and

introducer (L to R)

Tube length: Patients with very thick necks

can be fitted with a tracheostomy tube with

a flange that can be adjusted up or down

the shaft of the tube (Figure 12). Tube

length may also need to be adjusted when

the carina is close to the tracheostoma or

with tracheal stenosis or tracheamalacia

distal to the tracheostoma that needs to

stented by the tube. Chest and neck X-rays

are of value to determine the required

length.

Tube shape: Laryngectomy patients

require shorter tubes with a gentler

curvature to conform to the stoma and the

trachea.

Figure 12: Tracheostomy tube with

adjustable flange

Neck Flange: The neck flange should

conform to the shape of the neck and fit

snugly against the skin to avoid excessive

tube movement, accidental decannulation,

and soft tissue trauma.

Tube material: Metal tubes are thinner

walled, and hence have a better ratio of

outer to inner wall diameter, thereby

optimising airway resistance.

Phonation: Patients with uncuffed tubes or

fenestrated tubes (Figure 13) can phonate

by occluding the end of the tracheostomy

tube with a finger which permits air to

bypass the tube and to pass through the

larynx.

Figure 13: Fenestrated tracheostomy tube

7

Speaking valves fitted to the ends of

tracheostomy tubes are one-way valves

that open on inspiration, but close on

expiration, thereby directing expired air

through the larynx and permit hands-free

speech (Figure14).

Figure 14: Speaking valve that fits onto the

end of a tracheostomy tube and permits

hands-free speech

Fenestrated tubes with speaking valves are

particularly well suited to patients with

obstructive sleep apnoea, as they can have

normal speech by day with the valve in

place, but uncap the tracheostomy tube at

night to ensure unobstructed breathing.

Postoperative care

Pulmonary oedema: This may occur

following sudden relief of airway

obstruction and reduction in high

intraluminal airway pressures. It may be

corrected by CPAP or positive pressure

ventilation.

Respiratory arrest: This may occur

immediately following insertion of the

tracheostomy tube, and is attributed to the

rapid reduction in arterial pCO

2

following

restoration of normal ventilation, and

hence loss of respiratory drive.

Humidification: Tracheostomy bypasses

the nose and upper aerodigestive tract

which normally warms, filters, and

humidifies inspired air. To avoid tracheal

desiccation and damage to the respiratory

cilia and epithelium, and obstruction due to

mucous crusting, the tracheostomy patient

needs to breathe humidified warm air by

means of a humidifier, heat and moisture

exchange filter, or a tracheostomy bib.

Pulmonary Toilette: The presence of a

tracheostomy tube and inspiration of dry

air irritates the mucosa and increases

secretions. Tracheostomy also promotes

aspiration of saliva and food as tethering of

the airway prevents elevation of the larynx

during swallowing. Patients are unable to

clear secretions as effectively as

tracheostomy prevents generation of

subglottic pressure, hence making

coughing and clearing secretions

ineffective; it also disturbs ciliary function.

Therefore secretions need to be suctioned

in an aseptic and atraumatic manner.

Cleaning the tube: Airway resistance is

related to the 4

th

power of the radius with

laminar flow, and the 5

th

power of the

radius with turbulent flow. Therefore even

a small reduction of airway diameter

and/or conversion to turbulent airflow as a

result of secretions in the tube can

significantly affect airway resistance.

Therefore regular cleaning of the inner

cannula is required using a pipe cleaner or

brush.

Securing the tube: Accidental decannula-

tion and failure to quickly reinsert the tube

may be fatal. This is especially

problematic during the 1

st

48hrs when the

tracheocutaneous tract has not matured and

attempted reinsertion of the tube may be

complicated by the tube entering a false

tract. Therefore the tightness of the

tracheostomy tapes should be regularly

checked. Traction sutures on the tracheal

flap facilitate reinsertion of the

tracheotomy tube.

Cuff pressures: When tracheostomy tube

cuff pressures against the tracheal wall

mucosa exceed 30cm H

2

0, mucosal

capillary perfusion ceases, ischaemic

damage ensues and tracheal stenosis may

result. Mucosal injury has been shown to

8

occur within 15 minutes. Therefore cuff

inflation pressures of >25cm H

2

0 should be

avoided. A number of studies have

demonstrated the inadequacy of manual

palpation of the pilot balloon as a means to

estimate appropriate cuff pressures.

Measures to prevent cuff related injury

include:

Only to inflate the cuff if required

(ventilated, aspiration)

Minimal Occluding Volume Technique:

Deflate the cuff, and then slowly

reinflate until one can no longer hear

air going past the cuff with a

stethoscope applied to the side of the

neck near the tracheostomy tube

(ventilated patient)

Minimal Leak Technique: The same

procedure as above, except that once

the airway is sealed, slowly to

withdraw approximately 1ml of air so

that a slight leak is heard at the end of

inspiration

Pressure gauge: Regular or continuous

monitoring of cuff pressures

Decannulation

The tracheostomy tube can be removed

once the cause of the airway obstruction

has been resolved. If any doubt exists

about the adequacy of the airway, e.g.

following pharyngeal or laryngeal surgery,

then the tracheostomy tube is first

downsized and plugged, so that the patient

can breathe freely past the tube. The tube

is then plugged. The patient should be

under close observation during this time,

and may be monitored with pulse

oximetry. If the patient can tolerate the

tracheostomy tube being plugged

overnight, it can then be removed. The

tracheostomy wound is covered with an

occlusive dressing, and generally heals

over a matter a week.

Author & Editor

Johan Fagan MBChB, FCORL, MMed

Professor and Chairman

Division of Otolaryngology

University of Cape Town

Cape Town, South Africa

johannes.fagan@uct.ac.za

THE OPEN ACCESS ATLAS OF

OTOLARYNGOLOGY, HEAD &

NECK OPERATI VE SURGERY

www.entdev.uct.ac.za

The Open Access Atlas of Otolaryngology, Head &

Neck Operative Surgery by Johan Fagan (Editor)

johannes.fagan@uct.ac.za is licensed under a Creative

Commons Attribution - Non-Commercial 3.0 Unported

License

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- A Manual of the Operations of Surgery: For the Use of Senior Students, House Surgeons, and Junior PractitionersVon EverandA Manual of the Operations of Surgery: For the Use of Senior Students, House Surgeons, and Junior PractitionersNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthesia in Thoracic Surgery: Changes of ParadigmsVon EverandAnesthesia in Thoracic Surgery: Changes of ParadigmsManuel Granell GilNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument8 SeitenTracheostomyShar CatedralNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument63 SeitenTracheostomyAyesha FayyazNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy: As. Univ. Dr. Andrei Cristian Bobocea As. Univ. Dr. Serban Radu MatacheDokument21 SeitenTracheostomy: As. Univ. Dr. Andrei Cristian Bobocea As. Univ. Dr. Serban Radu MatacheIoana VasileNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument10 SeitenTracheostomyanitaabreu123Noch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy 191224152833Dokument106 SeitenTracheostomy 191224152833Dimas SevantoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tube ThoracostomyDokument6 SeitenChest Tube ThoracostomyRhea Lyn LamosteNoch keine Bewertungen

- CricothyroidotomyDokument38 SeitenCricothyroidotomyAlsalman AnamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tube InsertionDokument4 SeitenChest Tube InsertionHugo ARNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tension PneumothoraxDokument3 SeitenTension PneumothoraxariefNoch keine Bewertungen

- Cricothyroidotomy and Needle CricothyrotomyDokument10 SeitenCricothyroidotomy and Needle CricothyrotomyunderwinefxNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument27 SeitenTracheostomynahidanila439Noch keine Bewertungen

- Minor Surgical Procedures...Dokument10 SeitenMinor Surgical Procedures...Silinna May Lee SanicoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total LaryngectomyDokument14 SeitenTotal LaryngectomyDr. T. BalasubramanianNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total LaryngectomyDokument15 SeitenTotal LaryngectomyKumaran Bagavathi RagavanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tube Thoracostomy Chest Tube Implantation and Follow Up: Review ArticleDokument10 SeitenTube Thoracostomy Chest Tube Implantation and Follow Up: Review ArticleAnasthasia hutagalungNoch keine Bewertungen

- Total LaryngectomyDokument15 SeitenTotal LaryngectomyAdi SitaruNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy: Presented By: Barte, Hannah Aida D. Balamurugan, RameebhaDokument21 SeitenTracheostomy: Presented By: Barte, Hannah Aida D. Balamurugan, RameebhaThakoon Tts100% (1)

- Tracheostomy Operating TechniqueDokument34 SeitenTracheostomy Operating TechniqueIsa BasukiNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument4 SeitenTracheostomyNapieh Bulalaque PolisticoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Assignment On TreacheostomyDokument7 SeitenAssignment On Treacheostomysantosh kumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument3 SeitenTracheostomyJon AsuncionNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheotomyDokument19 SeitenTracheotomyKarina BundaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Filosso 2017Dokument11 SeitenFilosso 2017Allison DiêgoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy in Palliative CaraDokument9 SeitenTracheostomy in Palliative CarameritaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Annrcse01509 0sutureDokument3 SeitenAnnrcse01509 0sutureNichole Audrey SaavedraNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest TubeDokument18 SeitenChest TubeAyu MasturaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument28 SeitenTracheostomyprivatejarjarbinksNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheal TraumaDokument3 SeitenTracheal TraumaWalid DarwicheNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pneumothorax GuidelineDokument8 SeitenPneumothorax GuidelineIonut - Eugen IonitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Vertical Partial Laryngectomy An AtlasDokument14 SeitenVertical Partial Laryngectomy An AtlasDr. T. Balasubramanian100% (2)

- Anatomy of TracheostomyDokument4 SeitenAnatomy of TracheostomyShahabuddin ShaikhNoch keine Bewertungen

- MedSurg NotesDokument57 SeitenMedSurg NotesCHRISTOFER CORONADONoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy: Berlian Chevi A. 20184010030Dokument26 SeitenTracheostomy: Berlian Chevi A. 20184010030Berlian Chevi e'Xgepz ThrearsansNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tube InsertionDokument3 SeitenChest Tube InsertionprofarmahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy: Continuing Education ActivityDokument9 SeitenTracheostomy: Continuing Education ActivityUlul IsmiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tube InsertionDokument2 SeitenChest Tube InsertionmusicaBGNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy: Dr. Amar KumarDokument18 SeitenTracheostomy: Dr. Amar KumarSudhanshu ShekharNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thoracocentesis: Nadja E. SigristDokument4 SeitenThoracocentesis: Nadja E. SigristDwi AnaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Tubes and ThoracentesisDokument18 SeitenChest Tubes and ThoracentesisecleptosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Schellenberg 2018Dokument13 SeitenSchellenberg 2018Juan Jesús Espinoza AmayaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ThoracentesisDokument10 SeitenThoracentesisGabriel Friedman100% (1)

- Chest Tube Placement (Adult)Dokument8 SeitenChest Tube Placement (Adult)Ariane Joyce SalibioNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument58 SeitenTracheostomylissajanet1016100% (1)

- Percutaneous Tracheostomy: A Comprehensive Review.Dokument11 SeitenPercutaneous Tracheostomy: A Comprehensive Review.Hitomi-Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chest Drains Learning ResourceDokument22 SeitenChest Drains Learning ResourceSiriporn TalodkaewNoch keine Bewertungen

- Chapter 132 Total Penectomy. Hinman. 4th Ed. 2017Dokument3 SeitenChapter 132 Total Penectomy. Hinman. 4th Ed. 2017Urologi JuliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Howard B. Seim III, DVM, DACVS Colorado State University: WWW - VideovetorgDokument4 SeitenHoward B. Seim III, DVM, DACVS Colorado State University: WWW - VideovetorgIkhsan HidayatNoch keine Bewertungen

- Supraglottic LaryngectomyDokument5 SeitenSupraglottic LaryngectomyCarlesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ThoracentesisDokument12 SeitenThoracentesisAnusha Verghese0% (1)

- Amit Tracheostomy Presentation 12 Aug 2010Dokument59 SeitenAmit Tracheostomy Presentation 12 Aug 2010Amit KochetaNoch keine Bewertungen

- TracheostomyDokument35 SeitenTracheostomyAbdur Raqib100% (1)

- TracheostomyDokument6 SeitenTracheostomynamithaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thoracic Incisions PDFDokument14 SeitenThoracic Incisions PDFalbimar239512Noch keine Bewertungen

- Assisting With Chest Tube InsertionDokument5 SeitenAssisting With Chest Tube InsertionLoveSheryNoch keine Bewertungen

- Anesthetic Implications of Zenker's Diverticulum: Somasundaram Thiagarajah, Erwin Lear, and Margaret KehDokument3 SeitenAnesthetic Implications of Zenker's Diverticulum: Somasundaram Thiagarajah, Erwin Lear, and Margaret KehMatthew JohnsonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tracheostomy DR KVLN Rao PDFDokument33 SeitenTracheostomy DR KVLN Rao PDFVenkata Krishna Kanth ThippanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Difficult Acute Cholecystitis: Treatment and Technical IssuesVon EverandDifficult Acute Cholecystitis: Treatment and Technical IssuesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Break The Cycle Activity GuidesDokument19 SeitenBreak The Cycle Activity GuidesJuanmiguel Ocampo Dion SchpNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3 5 18 950 PDFDokument3 Seiten3 5 18 950 PDFBang AthanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Registrars Manual On Band DDokument32 SeitenRegistrars Manual On Band DkailasasundaramNoch keine Bewertungen

- SR.# Weight (KG) Height (FT) Age (Yrz) Others RecommendationsDokument2 SeitenSR.# Weight (KG) Height (FT) Age (Yrz) Others RecommendationsshaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Acuna - ENG 2089 AAEDokument2 SeitenAcuna - ENG 2089 AAERishi GolaniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Position PaperDokument2 SeitenPosition Paperiscream230% (1)

- Treatment and Prognosis of Febrile Seizures - UpToDateDokument14 SeitenTreatment and Prognosis of Febrile Seizures - UpToDateDinointernosNoch keine Bewertungen

- 5 Cover Letter Samples For Your Scientific ManuscriptDokument11 Seiten5 Cover Letter Samples For Your Scientific ManuscriptAlejandra J. Troncoso100% (2)

- YakultDokument15 SeitenYakultMlb T. De TorresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Gap AnalysisDokument9 SeitenGap Analysisapi-706947027Noch keine Bewertungen

- Power Development Through Complex Training For The.3Dokument14 SeitenPower Development Through Complex Training For The.3PabloAñonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Meditation ScriptDokument9 SeitenMeditation Scriptapi-361293242100% (1)

- Form2a 1Dokument2 SeitenForm2a 1ghi YoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Department of ICT Technology - DBMS Section: Level - IVDokument125 SeitenDepartment of ICT Technology - DBMS Section: Level - IVEsubalewNoch keine Bewertungen

- BLS Provider: Ma. Carmela C. VasquezDokument2 SeitenBLS Provider: Ma. Carmela C. VasquezPatricia VasquezNoch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS PDFDokument5 SeitenMSDS PDFdang2172014Noch keine Bewertungen

- Nzmail 18821014Dokument26 SeitenNzmail 18821014zeljkogrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nutritional Interventions PDFDokument17 SeitenNutritional Interventions PDFLalit MittalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Analysis & Distribution of The Syllabus Grade 11 English For Palestine Second Semester School Year: 20 - 20Dokument3 SeitenAnalysis & Distribution of The Syllabus Grade 11 English For Palestine Second Semester School Year: 20 - 20Nur IbrahimNoch keine Bewertungen

- Nah Incarcerated HerniaDokument4 SeitenNah Incarcerated Herniafelix_the_meowNoch keine Bewertungen

- How To File A Claim-For GSISDokument2 SeitenHow To File A Claim-For GSISZainal Abidin AliNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tano Vs SocratesDokument3 SeitenTano Vs SocratesNimpa PichayNoch keine Bewertungen

- Golf Proposal 09Dokument7 SeitenGolf Proposal 09nrajentranNoch keine Bewertungen

- Viroguard Sanitizer SDS-WatermartDokument7 SeitenViroguard Sanitizer SDS-WatermartIshara VithanaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PARCO Project HSE Closing ReportDokument22 SeitenPARCO Project HSE Closing ReportHabib UllahNoch keine Bewertungen

- Clinical Practice Guidelines: High-Grade Glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-UpDokument9 SeitenClinical Practice Guidelines: High-Grade Glioma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines For Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-UpSiva SubramaniamNoch keine Bewertungen

- 3M Disposable Filtering Facepiece Respirator Fitting Poster English and SpanishDokument2 Seiten3M Disposable Filtering Facepiece Respirator Fitting Poster English and SpanishTrunggana AbdulNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rdramirez Aota 2018 Poster For PortfolioDokument1 SeiteRdramirez Aota 2018 Poster For Portfolioapi-437843157Noch keine Bewertungen

- ProVari ManualDokument16 SeitenProVari ManualPatrickNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ethics of Helping Transgender Men and Women Have ChildrenDokument16 SeitenThe Ethics of Helping Transgender Men and Women Have ChildrenAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNoch keine Bewertungen