Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Deepening Democracy and Local Governance

Hochgeladen von

RajatBhatiaOriginalbeschreibung:

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Deepening Democracy and Local Governance

Hochgeladen von

RajatBhatiaCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

PERSPECTIVES

jUNE 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 42

Deepening Democracy

and Local Governance

Challenges before Kerala

M A Oommen

Keralas decentralised experience

has demonstrated that democracy

is more than just balloting. But

deepening democracy is a

continuous quest for justice and

freedom. While participatory

democracy has powerful

theoretical arguments, its

empirical basis continues to be

weak. This article explores how

far local governance in Kerala has

deepened democratic practice and

argues that the local governance

system in the state needs to be

reformed and redened.

K

eralas decentralised governance

is different from the rest of India

because it initiated institutional

reforms and moved ahead of others to

devolve powers, responsibilities and funds

to the local governments (LGs). After

nearly two decades of decentralisation

experience, this article explores two

questions. (1) How far has local govern-

ance in Kerala deepened democratic

practice? (2) What lessons does Kerala

offer to make democracy more meaning-

ful and valuable?

Conceptual Framework

Basically, deepening democracy means

making democracy relevant for the lives

that people live. The ideal conceptuali-

sation of democracy as the government

of the people, by the people, for the peo-

ple assumes meaning and content only

when its practice enhances the quality of

the lives that people live. Many includ-

ing scholars confuse democracy with

balloting and majority rule, and parti-

cipation as voting for competing elites

(e g, Schumpeter 1942, 1976; Huntington

1991). Far from it! Several institutions of

representative democracy, including the

party systems, are not fully answerable

and accountable to the people. In con-

cluding his edited volume that reviews

the journey of democracy from 508 BC

to 1993 AD, John Dunn (1992) points out

that present-day representative democ-

racy at best can provide only three serv-

ices: physical security, personal security

of subjects and the protection of a capi-

talist economy. Even at the height of its

present triumph, he points out that rep-

resentative demo cracy does not have

any unique claims to political authority.

For example, from the perspective of so-

cial justice and inclusive development,

representative demo cracy has no sup-

portive evidence or even arguments as a

unique form of organising political life for

the common good.

Deepening democracy is a continuous

process. It should be real at the local

community level. Hence it has a close

link to LGs. Two postulates that must

engage any quest towards deepening

democracy are: (a) the process should be

participatory and inclusive and (b) work

towards a strong public sphere. Partici-

pation in shaping peoples common

living is an intrinsic democratic value

which is realised best at the local level. A

lot depends on the quality of the institu-

tional arrangements created. While social

inclusion is an integral ingredient of

democracy, the terms of inclusion are

what make it meaningful. The appar-

ently inclusive caste system becomes

unacceptable because the terms of inclu-

sion of different people are iniquitous. A

society where inequality in income and

economic opportunities keeps widening,

even if there is poverty reduction, cannot

be inclusive. An inclusive democracy

should ensure dignity for all.

The idea of democracy as the use

of public reason has been advanced

by scholars like John Rawls, Jrgen

Habermas, Joshua Cohen, Amartya Sen

and several others. John Rawls A Theory

of Justice provides the moral basis for a

democratic society where justice is treated

as fairness. It is based on deliberative

rationality. As Rawls (1972: 4-5) observes:

[A] society is well-ordered when it is not

only designed to advance the good of its

members but when it is also effectively regu-

lated by a public conception of justice.

Rawls addresses the problems of social

and economic inequality as problems of

justice. For him inequalities in the distri-

bution of social and economic goods are

justied only if they work to the benet

of the most disadvantaged.

Habermas widens the scope of the

concept of democracy and treats demo-

cratisation as construction of public

sphere. For him, the public sphere

emerges historically as the result of a

process in which individual citizens are

made equal in their capability to demand

A summary of the keynote address delivered

at the opening session of the International

Conference on Deepening Democracy through

Local Governance (19-21 January 2014)

organised by the Government of Kerala at

Thiruvananthapuram.

M A Oommen (maoommen@gmail.com) is at

the Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi.

PERSPECTIVES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW jUNE 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25 43

from the ruling class public accountability

as well as moral justication for state

actions. Through his various writings

Habermas advanced a radical procedur-

alist model of deliberative democracy in

which all major political decision-making

is linked to discursive processes of a

political public sphere. Here administra-

tive decisions reect the consensus that

emerges at the level of the public opinion.

However, in most democracies in con-

temporary world, the collapse of public

sphere is very perceptible. But publicity

continues to be an organisational principle

of our political order (Habermas 1991: 4).

So long as publicity is an accepted prin-

ciple of contemporary world, the case for

building a rational public sphere is un-

assailable. Wrong publicity can have

dangerous consequences. The question

of making public sphere meaningful and

dynamic in social life is, therefore, the

key to democratising democracy. In the

public sphere, new issues, new actors

(workers, women, marginalised people,

etc) come forward and argue out their

case by appealing to the best of reason.

This is the only way to break the elitistic

democratic traditions. To quote Habermas

(1984, Vol 1: 397):

If we assume that the human species main-

tains itself through the socially coordinated

activities of its members and that this coor-

dination has to be established through com-

munication and in certain central spheres

through communication aimed at reaching

agreement then the reproduction of the

species also requires satisfying the conditions

of rationality that is inherent in communica-

tive action.

In a later work Habermas (1996: 367)

points out:

the communication structures of the pub-

lic sphere must be kept alive by an active

civil society. The core of civil society com-

prises a network of associations that institu-

tionalises problems-solving discussion on

questions of general interest inside the

framework of organised public spheres.

He thus assigns a key role to civil society.

Given the diverse typology of civil society,

it is difcult to identify the truly demo-

cratic agents of social change. Habermas

is for a civil society that draws its suste-

nance from the everyday life of the people.

The quality of public sphere depends

on how best it is inuenced by public

reason without being manipulated by

populist leaders, and vested interests

which include the media. Habermas

highlights normative standards the me-

dia should follow to have meaningful

deliberative politics and public sphere.

He assumes that the public processes of

communication can take place with less

distortion the more they are left to the

internal dynamics of a civil society that

emerges from the life-world. The media

and political parties will also have

to participate in the opinion and will-

formation from the publics own perspec-

tive rather than patronising them and

extracting mass loyalty from the public

sphere for staying in power (ibid: 379).

Sometimes intellectuals and concerned

citizens raise issues which nd a natural

entry into mass media and from that

into public agenda. In brief, building and

maintaining a key public sphere based

on public reason is crucial to a good

democratic society. But Habermas is

criticised for not providing the link

between pubic reason and public policy

changes. Further his exclusive emphasis

on consensus as the aim of communica-

tion and his inadequate appreciation of

differences and dissent as something

necessarily to be overcome do not seem

to be practicable. Even so, his contribu-

tion to the theory and practice of demo-

cracy remains signicant.

Joshua Cohen, like Habermas, is a

radical democrat who owes a great deal

to the ideas of discursive democracy

of the latter. Surely, what we are looking

at is not aggregation of individual inter-

ests, but reasoned public outcome. But

this is a formidable task because of the

realities of organised social and admin-

istrative power. Cohen suggests direct-

ly-deliberative polyarchy (1999: 411) as

a practical improvement on Habermas.

While recognising the limits of legisla-

ture and administration in problem-

solving, he seeks to empower and facili-

tate it through directly-deliberative arenas

operating in closer proximity than the

legislature to the problem (ibid: 413).

The legislature can even declare certain

areas of policy such as education, en-

vironmental health, etc, to be addressed

by deliberative polyarchic action. There

are several areas and ways in which

democratic values and problem-solving

can be linked.

Amartya Sen is another scholar who

works for improving the quality of de-

mocracy. Besides his prolic writings on

agency, rights, capabilities and freedom,

he argues for a government by discus-

sion, based on public reason (the latter

idea he elaborates in his The Idea of

Justice). Sen critically supports Rawls,

Cohen and Habermas. He points out how

important openness of communication

and argument is for formation of value

(Sen 2009: 336).

Fundamental Values

In short, deliberation, building a public

sphere, direct participation of citizens

and working towards an inclusive society

are all fundamental democratic values.

Deepening democracy cannot be con-

ceptualised without reference to these

values which are critical for working

towards responsive, accountable and

participatory local governance. Boadway

and Shah (2009: 242) dene local gov-

ernance thus:

Good local governance is not just about pro-

viding a range of local services but also

about preserving the life and liberty of resi-

dents, creating space for democratic partici-

pation and civic dialogue, supporting market-

led and environmentally sustainable local

development, and facilitating outcomes that

enrich the quality of life of residents.

This is a comprehensive denition of

local governance. Given adequate support

through institutional reforms (as Kerala

has done), the 73rd/74th Constitutional

Amendments open great possibilities for

building local democracy. Contrary to

what scholars like Bardhan (2002) argue,

the approach underlying these amend-

ments is not to be considered as an ex-

tension of the scal federalism literature

of the west. The gram sabha (village

assembly) where all citizens are expected

to participate and deliberate on the

working of their LG, the constitutional

mandate to create institutions of self-

government to plan for economic devel-

opment and social justice, the establish-

ment of the district planning committee

(DPC) to consolidate local plans at the

district level and so on do not mesh well

with the scal federa lism postulates.

1

Keralas initiatives in institutionalising

several participatory mechanisms for

decentralised planning, devolution of

PERSPECTIVES

jUNE 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 44

substantial investible resources to LGs,

enlisting support of women neighbour-

hood groups to bridge the gap between

LGs and communities are far removed

from the known norms of scal federalism.

Decentralisation:

Some Magnitudes and Trends

The degree of decentralisation to LGs

may be measured in terms of (a) the

magnitude of resources notably investi-

ble resources devolved by the higher

level governments to the LGs and the au-

tonomy given to manage them; (b) the

percentage of local expenditure to the

total public expenditure; and (c) local

expenditure as a percentage of gross

domestic product (GDP)/state domestic

product (SDP).

The rst major decision of the Left

Democratic Front (LDF) government that

came to power in mid-July 1996 was to

transfer 35-40% of the state plan outlay

(based on valid estimates) to LGs. This

was followed by the initiative of the

State Planning Board which worked out

through a learning by doing exercise, a

methodology for decentralised planning

to be pursued autonomously by the

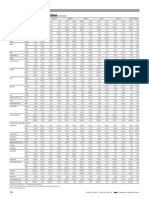

LGs. Table 1 shows two measures of

devolution, viz, the ratio of LG plan

grant to state plan outlay and total

transfers as a ratio of states own tax

revenue (SOTR).

It is clear from Table 1 that

on an average from 1997-98

to 2011-12 the state has de-

volved nearly 25% of its in-

vestible resources (develop-

ment fund/plan outlay) to

the LGs and the annual devo-

lution ranges from 20.65% in

2009-10 to 33.33% in 2002-03.

The gure shows the per

capita transfers. Although the

nominal per capita transfers

show an almost steady in-

crease (1.53% per annum),

the real per capita numbers

using SDP deators at 1993-94

prices (with 1997-98=100)

increased only at a slower

pace (0.73%). The 15-year

average of the total resource

transfers including non-plan

transfers vis--vis the total

state tax revenue works out to 18.48%.

Although this is not a small achievement

in terms of the magnitude of devolution,

the steady decline in the fund ow to LGs

as a percentage of SOTR is a disturbing

one. In fact, in 1998-99, it was as high

as 28.7%, but declined to 14.87% in

2010-11. Although the LGs did not share

states tax revenue buoyancy, the per capi-

ta real transfers did not register a fall.

From a negligible share of a little over

4% of public expenditure and 0.73% of net

state domestic product (NSDP) in 1993-94,

there was a threefold jump to 12.04% and

2.40%, respectively, in 1998-99. These

were more or less stably maintained till

2011-12. But when compared to several

other countries, such as Latin America,

South Africa, not to speak of the Nordic

countries, Kerala lags way behind in

terms of public expenditure share and

GDP share (World Bank 2008: 296). The

development funds (previously called

plan grants) devolved are untied investi-

ble resources. The major conditionality

for the entitlement of plan grants by a LG

is the formulation and implementation of

a local plan. The creation of a multistage

process of planning, starting from call-

ing the ward sabha to identifying the

felt needs of the citizens, discussions at

the development seminar to projectisa-

tion by the various working groups, vet-

ting by technical advisory group and -

nal clearance by the DPC, has widened

the avenues for participation by people.

But deepening democracy is a continuous

pursuit. Unless assidu ously fostered, slip-

pages are bound to happen. The conclu-

sions of a Government of Kerala Report

(2009) appointed to evaluate decentrali-

sation are worth recalling:

When a great effort gets ritualised you cele-

brate the shadow; local democracy and the

multi-stage process of decentralisation re-

main in retreat. Fall in Gram Sabha/Ward

Sabha attendance, and manipulation of it,

the studied shying away by the upper class

and educated from Gram/Ward Sabha meet-

ings, the lling of expert bodies with parti-

sans (Working Group, Technical Advisory

Group, etc), preparation of projects by

clerks, complete lack of professionalism and

team work among DPC members and so on

have made decentralised governance a cari-

cature of what it ought to be (p 62).

Probably much could not be expected

in terms of deepening democratic prac-

tice so long as the entire process was

tied down to routine formulations of

annual plans.

Issues and Challenges

Strong political will to decentralise

along with efforts towards converting

every ward into a gram sabha for articu-

lating peoples preferences and evolving

a participatory methodology laid the

Table 1: Trend in the Devolution of Resources to Local

Governments (by the Kerala State Government 1997-98 2011-12)

Year Ratio of LG Total Transfers Per Capita Per Capita

Plan Grant to to LGs Transfers Transfers in

State Plan (Plan + Non- Plan) (Rs) Real Terms at

Outlay as Percentage 1993-94 Prices

of SOTR (Rs)

1997-98 26.23 23.24 337.07 337.07

1998-99 30.65 28.7 429.89 339.81

1999-2000 31.38 27.45 459.24 342.41

2000-01 29.56 24.95 471.97 344.88

2001-02 28.19 21.79 415.91 347.21

2002-03 33.33 24.84 584.51 350.81

2003-04 29.73 22.53 587.22 353.94

2004-05 28.13 20.99 606.06 357.02

2005-06 25.61 20.78 654.75 360.05

2006-07 22.54 17.17 660.48 363.00

2007-08 22.14 16.63 732.47 365.91

2008-09 21.69 15.36 791.5 368.78

2009-10 20.65 15.56 872.3 371.58

2010-11 22.72 14.87 1040.46 374.31

2011-12 23.24 15.45 1280.27 376.93

15 Year Ratio 24.98 18.48 624.82 356.91

Source: Worked out from CAG Reports for various years and Government of

Kerala (2011) and SOTR from Budget in Brief (various years), Government of

Kerala.

Figure: Per Capita Transfers in Nominal and Real Terms

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1997-98 1998-99 1999-2000 2000-01 2001-02 2002-03 2003-04 2004-05 2005-06 2006-07 2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12

Per capita transfers in real term at 1993-94

base using SDP deflators

Nominal per capita transfers

PERSPECTIVES

Economic & Political Weekly EPW jUNE 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25 45

foundations for decentralised democratic

planning in Kerala. It demonstrated to

the world the powerful lesson that demo-

cracy is about more than balloting. But

deepening democracy is a continuous

quest with considerable instrumental

value for justice and freedom. It needs

progressive support. This has been a

great casualty. I wish to raise two general

postulates as already noted and some

specic issues that are fundamental to

strengthen the process of local govern-

ance in the state.

First, Keralas local governance should

be yoked to the goal of inclusive society.

Our concept of inclusive society is dif-

ferent from the amorphous concept of

inclusive growth

2

which is the avowed

goal set by the Eleventh and Twelfth

Five-Year Plans before the nation. As al-

ready noted, the terms of inclusion are

more important than the fact of inclu-

sion via a trickle down growth process. I

have argued elsewhere (Oommen 2013)

that reckoned in terms of measures of

distribution of land, per capita consumer

expenditure, wage income differentials,

social security entitlements and the like,

Kerala confronts growing inequalities.

Besides that, the service-led high growth

of the state during the last decade has

created a dual channelisation, modern

and traditional, that considerably accen-

tuates the polarised process of inequality.

The sherfolk, scheduled castes (SCs)

and scheduled tribes (STs) continue to

remain marginalised (for detailed evi-

dence, see GoK 2011, chapter 8). This

phenomenon cannot be ignored by any-

one genuinely concerned with deepen-

ing democracy. While LG projects like

Ashraya (a project to identify and reha-

bilitate the poorest of the poor in a LG)

as well as the recommendation of the

Fourth State Finance Commission for

inclusion of the excluded are impor-

tant steps the problem of inequality and

growing marginalisation of the poor

needs a comprehensive approach and

clear policy choices.

The second postulate relates to the

promotion of the idea of democracy as the

use of public reason. Although Keralas

public action tradition has been highly

commented upon by several scholars

(e g, Dreze and Sen 1989, 1995, 2002;

Jeffrey 1993), a public sphere, based on

public reason, has yet to take a rm shape

in Kerala. Public reason and the politics

of voice in Kerala including the ubiquitous

media have failed to become a counter

force to the endemic vested interests,

communalism, clientelism, alcoholism

and several other negative factors that

envelop Kerala society today. No civil

society of Kerala seems to be seized

of the matter. Even such mass-based

organisations like the Kudumbashree

and the Kerala Sasthra Sahitya Parishad

need considerable reorientation to be

the voice of reason and common good.

The gram sabha which was very active

during the early days of decentralised

planning has failed to become a local

public sphere.

The manner in which several issues

which are vital to the well-being of the

people and the future of local democracy

in the state were debated and responded

shows that public reason and scientic

communication are in retreat. That the

predators of nature could successfully

persuade the political parties and the

central and state governments to bypass

the reasonings of the Western Ghats Eco-

logy Expert Panel (widely known as the

Gadgil Committee) including their argu-

ment that ultimate decisions on local

space rest with the gram sabha shows that

public reason is at a discount. Even so,

that the people of Plachimada panchayat

in the Palakkad district, despite initial

resistance, successfully fought their case

against Coca-Cola on the basis of scien-

tic facts relating to pollution and deple-

tion of groundwater shows that proper

communication and public reason could

be made the basis for deepening demo-

cracy and building local public sphere in

Kerala. But these are exceptions, and

certainly not the rule.

Conclusions

There are four specic issues that need

to be addressed to strengthen local gov-

ernance in the state. First, the nancial

reporting system of LGs in Kerala contin-

ues to be generally unreliable, irregular

and inconsistent. Good nancial report-

ing is the key to proper monitoring,

good nancial management and the

best way to reduce corruption. Keralas

local government needs con sistent data

at least for seven accounts (development

fund, state-sponsored schemes, general

purpose fund, maintenance fund, centrally-

sponsored schemes (CSSs), own source

revenue and borrowed funds) for the

ve tiers (district panchayat, block

panchayat and gram panchayat, corpo-

rations and municipalities) of the local

governance system. This can happen

meaningfully only when LG budgeting

is made an integral tool of scal man-

agement. But most LGs treat budgeting

as a necessary evil. Local budgets do not

attract debates as at the state and union

level. The income expenditure numbers

given have no sanctity. Budgets are

not strategically tied to planning. It is

difcult to obtain valid and consistent

budget data, annual nancial statements,

demand, collection and balance (DCB)

data, and so on from most of the LGs.

That all the 1,209 LGs have internet

connectivity and they are currently net-

worked through the Information Kerala

Mission offers hope for building trans-

parent and accountable local govern-

ance in the state. This is a major chal-

lenge. In most municipal budgets of the

world, such as in Brazil, the local budget

is the point of peoples entry.

Second, over the years the decentral-

ised planning methodology followed in

Kerala has changed not necessarily for

the better. While changes are needed

they should work towards more demo-

cratisation. The hallmark of decentral-

ised planning in its earlier vintage was

the participatory structures such as the

gram sabha meeting, the working group

for projectisation and the development

seminar. The latest guidelines, however,

involve 14 stages and each stage is guided

by the rule book and bureaucracy.

3

So

long as planning is a routinised annual

exercise, democratic participation loses

meaning. It is for the local people

to prepare the vision of their future

deve lopment, their sectoral perspective,

planned development trajectory, and so

on. But mixing up administrative and

pro fessional responsibilities with parti-

cipation of people in regard to vision

statement, expression of priorities,

moni toring and so on, can be confusing

and at times counterproductive. In this

PERSPECTIVES

jUNE 21, 2014 vol xlix no 25 EPW Economic & Political Weekly 46

context, the following ndings of an

informed scholar need to be taken up for

further debate:

Citizens and participatory spaces will con-

tinue to partake in imagining future devel-

opment, identifying development needs and

problems, deliberating on alternative solu-

tions, helping formulate projects, forming

public opinion on prioritisation, reviewing

development intervention by different tiers

of government, and above all demanding re-

sponsiveness and accountability. But par-

ticipatory institutions will not take over pub-

lic administration or replace experts/admin-

istrative agencies (Harilal 2013: 59).

In order to promote the democratisa-

tion process, all executive and statutory

measures should facilitate the process of

democratisation. Although preparation

of the long-term district development

plan (Article 234 ZD) could be an ideal

platform for people, administration and

technocrats to cooperate, Kerala has yet

to make it an integral part of the states

development landscape. The multiplici-

ty of guidelines that the central govern-

ment and the Planning Commission

have issued in the context of various

CSSs has added confusion to the making

of district planning. Keralas Kollam

District Plan is widely acknowledged as

a realistic methodology with a partici-

patory approach (GoI 2013: 487) and

certainly needs to be given a fair trial in

the state. How far it could be made an

instrument for deepening democracy

through local governance is a challenge

not only for the state, but also for

the nation.

Third, while public health is a joint

responsibility of all tiers of government,

waste management is the primary respon-

sibility of LGs. The return of vector-borne

diseases like malaria, dengue fever and

the like has placed the proverbial public

health model of Kerala under threat. I

wish to draw particular attention to

Chapter III of Report of the Comptroller

and Auditor General of India (Local Self-

Government Institutions) for the Year

Ending March 2011 on Thiruvanantha-

puram Corporation to illustrate that rea-

sons and facts have been sidelined on

vital issues. The corporation and the

states public health department col-

lectively will have to see why vector-

borne diseases have come back with a

vengeance. Apportioning blame and

engaging in a war of words is a political

game for evading issues and certainly

not the way of public reason.

Fourth, the trifurcation of the local

government administration of Kerala

under three separate ministries effected

from May 2011 goes counter to the con-

stitutional mandate to create organic

institutions of self-government at the

local level. Deepening democracy through

local governance is a great vision and

has to be fostered in an integrated fash-

ion. The mandated district plan formula-

tion requires an integrated planning of

the district space as a whole and calls for

comprehensive solutions. Political com-

promises do not stand scrutiny at the

court of public reason.

To conclude, Keralas decentralised

experience has demonstrated that demo-

cracy is about more than balloting. But

deepening democracy is a continuous

quest for justice and freedom. While

participatory democracy has powerful

theoretical arguments, its empirical basis

continues to be weak. Local governance

system needs to be reformed and rede-

ned as an ongoing project. A society

where inequality in income and eco-

nomic opportunities keep widening, even

when poverty is reduced, is not socially

inclusive. Kerala has a very dynamic and

politically active public, but its associa-

tional life is getting highly fragmented.

There is a need to strengthen the

communicative system based on public

reason so that Keralas public sphere,

including its local public sphere, gets

progressively oriented on a rational

democratic footing.

Notes

1 The scal federalism literature is best presented

in Oates (1972, 1999). For a brief review of

scal federalism literature and their relevance

for Indian local governments see Oommen

(2005).

2 On this see Oommen (2011).

3 Government of Kerala (2013), Twelfth Five-Year

Plan (2012-17); LSGI Plan Formulation, Subsidies

and Allied Subjects Related Guidelines, GO/

M.S/No.362/2013 LSGI, Thiruvananthapuram,

16 January 2013.

References

Bardhan, Pranab (2002): Decentralisation of

Governance and Development, Journal of

Economic Perspectives, Vol 16, No 4.

Boadway Robin and Anwar Shah (2009): Fiscal

Federalism: Principles and Practice of

Multi- order Governance (New York: Cambridge

University Press).

Cohen, Joshua (1999): Reections on Habermas

on Democracy, Ratio Juris, Vol 12, No 4.

Dreze, Jean and Amartya Sen (1989): Hunger and

Public Action (Oxford: Clarendon Press).

(1995): India: Economic Development and Social

Opportunity (New Delhi: Oxford University

Press).

(2002): India: Development and Participation

(New Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Dunn, John, ed. (1992): Democracy: The Unnished

Journey 508 BC to AD 1993 (New York: Oxford

University Press).

GoI (2011): Report of the Western Ghats Ecology

Expert Panel, The Ministry of Environment and

Forests, Government of India, New Delhi.

(2013): Towards Holistic Panchayat Raj,

Twentieth Anniversary Report of the Expert

Committee on Leveraging Panchayats for Ef-

cient Delivery of Public Goods and Services, Gov-

ernment of India, New Delhi.

GoK (2009): Report on Committee for Evaluation

of Decentralised Planning and Development,

Government of Kerala, Thiruvananthapuram.

(2011): Report of the Fourth State Finance

Commission Vol I & II, Government of Kerala,

Thiruvananthapuram.

Habermas, Jurgen (1984): The Theory of Communi-

cative Action, translated by Thomas Burger

with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence

(Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press).

(1991): The Structural Transformation of the

Public Sphere, translated by Thomas Burger

with the assistance of Frederick Lawrence

(Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press).

(1996): Between Facts and Norms, translated by

William Rehg (Cambridge, Massachusetts:

MIT Press).

Harilal, K N (2013): Confronting Bureaucratic

Capture: Rethinking Participatory Planning

Methodology in Kerala, Economic & Political

Weekly, Vol XLVIII, No 36, September.

Huntington, Samuel P (1991): How Countries Demo-

cratise, Political Science Quarterly, Vol 106,

No4 (Winter 1991-92).

Jeffrey, Robin (1993): Politics, Women and Well-

being (New Delhi: Oxford University Press).

Oates, Wallace E (1972): Fiscal Federalism (New

York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich Inc).

(1999): An Essay on Fiscal Federalism, Jour-

nal of Economic Literature, 37, September.

Oommen, M A (2005): Rural Fiscal Decentralisa-

tion in India: A Brief Review of Literature in

L C Jain (ed.), Decentralisation and Local Gov-

ernance (New Delhi: Orient Longman).

(2011): On the Issue of Inclusive Growth ,

Economic & Political Weekly, Vol XLVI, No 29.

(2013): Growth, Inequality and Well Being:

Revisiting Fifty Years of Keralas Development

Trajectory (under publication).

Rawls, John (1972): A Theory of Justice (Oxford:

Clarendon Press).

Schumpeter, A Joseph (1942, 1976): Capitalism,

Socialism and Democracy, Fifth Edition (New

South Wales, The United Kingdom: George

Allen & Unwin).

Sen, Amartya (2009): The Idea of Justice (London,

Allen Lane, Penguin Books).

World Bank (2008): Decentralisation and Local

Democracy in the World (Washington DC:

The World Bank and United Cities and Local

Governments).

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Racial Contract PDFDokument90 SeitenThe Racial Contract PDFSam Greenwald100% (1)

- The Internet and Democratization of Civic CultureDokument20 SeitenThe Internet and Democratization of Civic CultureAna Isabel PontesNoch keine Bewertungen

- Biesta - The Ignorant Citizen - Mouffe, Re and The SubjectDokument13 SeitenBiesta - The Ignorant Citizen - Mouffe, Re and The SubjectDoron HassidimNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Yale Philosophy Review N3 2007Dokument99 SeitenThe Yale Philosophy Review N3 2007Martha Herrera100% (1)

- Library and Information Science Unit: Republic of The Philippines Leyte Normal UniversityDokument5 SeitenLibrary and Information Science Unit: Republic of The Philippines Leyte Normal UniversityVivian DavinesNoch keine Bewertungen

- David A. Crocker-Ethics of Global Development - Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy-Cambridge University Press (2008) PDFDokument432 SeitenDavid A. Crocker-Ethics of Global Development - Agency, Capability, and Deliberative Democracy-Cambridge University Press (2008) PDFDeborahDelNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democratic Theory Paper 1Dokument7 SeitenDemocratic Theory Paper 1Eddie Smith100% (1)

- The Relationship Between Participatory Democracy and Digital Transformation in TanzaniaDokument23 SeitenThe Relationship Between Participatory Democracy and Digital Transformation in TanzaniaBarikiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Jurgen Habermas - Political Communication in Media Society - Does Democracy Still Enjoy An Epistemic DimensionDokument16 SeitenJurgen Habermas - Political Communication in Media Society - Does Democracy Still Enjoy An Epistemic DimensionAlvaro EncinaNoch keine Bewertungen

- 04 HellerDokument43 Seiten04 HellerTarek El KadyNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deliberative Democracy and Digital Sphere (For Book Bind)Dokument3 SeitenDeliberative Democracy and Digital Sphere (For Book Bind)Arvhie SantosNoch keine Bewertungen

- Castiglione Warren - Eight Theoretical Issues 2006Dokument11 SeitenCastiglione Warren - Eight Theoretical Issues 2006Jefferson ZarpelaoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy and DevelopmentDokument17 SeitenDemocracy and Developmentcurlicue100% (1)

- Psda of Political ScienceDokument10 SeitenPsda of Political ScienceKumar ShubhamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Governance Driven DemocratizationDokument12 SeitenGovernance Driven Democratizations7kkgjqvgcNoch keine Bewertungen

- Debate On The Democracy of The Future, in The Digital Era (From Theory To Practice)Dokument49 SeitenDebate On The Democracy of The Future, in The Digital Era (From Theory To Practice)AJHSSR JournalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Melucci, Alberto & Avritzer, Leonardo - Complexity, Cultural Pluralism and Democracy - Collective Action in The Public Space (Article) 2000Dokument21 SeitenMelucci, Alberto & Avritzer, Leonardo - Complexity, Cultural Pluralism and Democracy - Collective Action in The Public Space (Article) 2000saintsimonianoNoch keine Bewertungen

- POLGOV Finals ReviewerDokument22 SeitenPOLGOV Finals ReviewerFrancine Nicole AngNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Internet and The Democratization of Civic CultureDokument6 SeitenThe Internet and The Democratization of Civic CultureAram SinnreichNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philo 1Dokument3 SeitenPhilo 1Keithlyn KellyNoch keine Bewertungen

- HonnethDokument22 SeitenHonnethhonwanaamanda1Noch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy As Reflexive Cooperation - Dewey and Theory of Democracy (A. Honneth)Dokument22 SeitenDemocracy As Reflexive Cooperation - Dewey and Theory of Democracy (A. Honneth)Juan Pablo Serra BellverNoch keine Bewertungen

- Kenneth Baynes: Deliberative Democracy and The Limits of LiberalismDokument16 SeitenKenneth Baynes: Deliberative Democracy and The Limits of LiberalismRidwan SidhartaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracia Social WikipediaDokument4 SeitenDemocracia Social Wikipediacochi2011Noch keine Bewertungen

- The Democratic SocietyDokument11 SeitenThe Democratic SocietyBernardo Cielo IINoch keine Bewertungen

- COHEN - Reflections On Habermas On Democracy PDFDokument32 SeitenCOHEN - Reflections On Habermas On Democracy PDFJulián GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- 4TH EDITHA Instructured Module in TrendsDokument42 Seiten4TH EDITHA Instructured Module in TrendsEditha FernandezNoch keine Bewertungen

- LESSON 3 Concepts of DemocracyDokument21 SeitenLESSON 3 Concepts of Democracynathaniel zNoch keine Bewertungen

- Pragmatic DemocracyDokument13 SeitenPragmatic Democracyapi-596515120Noch keine Bewertungen

- Insights IAS Revision Plan For UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Exam 2018 Sheet1 6Dokument12 SeitenInsights IAS Revision Plan For UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Exam 2018 Sheet1 6Sundar MechNoch keine Bewertungen

- BOHMAN - The Coming Age of Deliberative DemocracyDokument26 SeitenBOHMAN - The Coming Age of Deliberative DemocracyJulián GonzálezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Constellations - 2023 - Chambers - Deliberative Democracy and The Digital Public Sphere Asymmetrical Fragmentation As ADokument8 SeitenConstellations - 2023 - Chambers - Deliberative Democracy and The Digital Public Sphere Asymmetrical Fragmentation As ASorin BorzaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Facets of The Public SphereDokument25 SeitenFacets of The Public SphereAndrea PérezNoch keine Bewertungen

- Institutional Design and Public SpaceDokument17 SeitenInstitutional Design and Public SpaceAnonymous XVN2Ld57Noch keine Bewertungen

- Social Justice and Communication Mill MarxDokument22 SeitenSocial Justice and Communication Mill MarxGidafianNoch keine Bewertungen

- DemocracyDokument9 SeitenDemocracyChief Comrade ZedNoch keine Bewertungen

- 28 - Riker81 - Confrontation Social Choice-Democracy - Literature Week 6Dokument25 Seiten28 - Riker81 - Confrontation Social Choice-Democracy - Literature Week 6Corrado BisottoNoch keine Bewertungen

- C Mouffe AgonismDokument15 SeitenC Mouffe AgonismVictoire GueroultNoch keine Bewertungen

- Representation Deliberation Civil SocietyDokument20 SeitenRepresentation Deliberation Civil SocietyMarc CanvellNoch keine Bewertungen

- TH Marshall MaastrichtDokument24 SeitenTH Marshall MaastrichtabdulqadirNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy and Democratic Participation in The SocietyDokument15 SeitenDemocracy and Democratic Participation in The SocietyFranz Anthony Quirit GoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Conceptualizing Difference The Normative Core of DDokument19 SeitenConceptualizing Difference The Normative Core of DgerryNoch keine Bewertungen

- The National Law Institute University Bhopal: Trimester IiiDokument5 SeitenThe National Law Institute University Bhopal: Trimester IiiGuddu SinghNoch keine Bewertungen

- Which Conception of Political Equality Do Deliberative Mini-Publics Promote?Dokument22 SeitenWhich Conception of Political Equality Do Deliberative Mini-Publics Promote?Enrique Sotomayor TrellesNoch keine Bewertungen

- ParticipismDokument5 SeitenParticipismSsmdvdNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deliberative Democracy Essays On Reason and PoliticsDokument478 SeitenDeliberative Democracy Essays On Reason and PoliticsMariana Mendívil100% (4)

- Pts 144Dokument10 SeitenPts 144Kim EcarmaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Electronic Media and Civil Society Barbara Becker and Josef Wehner GMDDokument10 SeitenElectronic Media and Civil Society Barbara Becker and Josef Wehner GMDMohd ZulfadliNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Role of Civil Society in Contributing To Democracy in BangladeshDokument14 SeitenThe Role of Civil Society in Contributing To Democracy in BangladeshMostafa Amir Sabbih100% (1)

- Phil Term Paper 2Dokument7 SeitenPhil Term Paper 2Christopher SchubertNoch keine Bewertungen

- LEYDET 2019 ¿Which Conception of Political Equality Do Deliberative Mini-Publics PromoteDokument22 SeitenLEYDET 2019 ¿Which Conception of Political Equality Do Deliberative Mini-Publics Promoted31280Noch keine Bewertungen

- Comment On Held's From Executive To Cosmopolitan Multilateral IsmDokument7 SeitenComment On Held's From Executive To Cosmopolitan Multilateral IsmmarlinbennettNoch keine Bewertungen

- ItPS Outline Unit 04 The Meaning of DemocracyDokument19 SeitenItPS Outline Unit 04 The Meaning of DemocracyAres SieteNoch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy 4Dokument12 SeitenDemocracy 4durva.juaria8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Denhardt and Denhardt, "The New Public Service": "Serve Citizens, Not Customers"Dokument8 SeitenDenhardt and Denhardt, "The New Public Service": "Serve Citizens, Not Customers"saittawut100% (4)

- F - Edited TasneemSultanaDokument25 SeitenF - Edited TasneemSultanaBimen NakalNoch keine Bewertungen

- Deliberation Before The RevolutionDokument23 SeitenDeliberation Before The RevolutionErica_Anita_7272Noch keine Bewertungen

- Democracy and Other GoodsDokument26 SeitenDemocracy and Other GoodsHéctor FloresNoch keine Bewertungen

- Islam and DemocracyDokument12 SeitenIslam and DemocracyArina SyamNoch keine Bewertungen

- Probability of Majority Decisions (1785), He Encouraged A Specific Voting System, PairwiseDokument8 SeitenProbability of Majority Decisions (1785), He Encouraged A Specific Voting System, PairwiseAshley LapusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rights, Culture and DemocracyDokument20 SeitenRights, Culture and DemocracyGabriela MessiasNoch keine Bewertungen

- SkaaningDokument18 SeitenSkaaningAceNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Ehsan Jafri CaseDokument3 SeitenThe Ehsan Jafri CaseRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Safe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityDokument6 SeitenSafe Drinking Water in Slums: From Water Coverage To Water QualityRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Trends in Agricultural ProductionDokument1 SeiteTrends in Agricultural ProductionRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Discreet Charm of The BJPDokument4 SeitenThe Discreet Charm of The BJPRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanDokument2 SeitenPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Shobhit MahajanRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Making Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceDokument3 SeitenMaking Sense of India's "Democratic" ChoiceRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- PS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiDokument2 SeitenPS XLIX 24 140614 Postscript Avishek ParuiRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Indias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreDokument1 SeiteIndias Quarterly GDP Estimates at Factor Cost by Economic Activity Rs CroreRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Known Unknowns of RTIDokument7 SeitenKnown Unknowns of RTIRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- From 50 Years AgoDokument1 SeiteFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- ED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleDokument1 SeiteED XLIX 24 140614 Mission ImpossibleRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- What Future For The Media in IndiaDokument3 SeitenWhat Future For The Media in IndiaRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Revisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaDokument5 SeitenRevisiting DroughtProne Districts in IndiaRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Lessons From A HangingDokument1 SeiteLessons From A HangingRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Homage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryDokument2 SeitenHomage To A Critic of MarxistPositivist HistoryRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- From 50 Years AgoDokument1 SeiteFrom 50 Years AgoRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Decoding Dravidian PoliticsDokument4 SeitenDecoding Dravidian PoliticsRajatBhatia100% (1)

- Beautiful Game Ugly AdministrationDokument2 SeitenBeautiful Game Ugly AdministrationRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Akshardham Judgment IDokument3 SeitenAkshardham Judgment IRajatBhatiaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Rawls Theory of JusticeDokument4 SeitenRawls Theory of JusticevidushiiiNoch keine Bewertungen

- MGT610 - Final Term Notes 1-Pages-2Dokument110 SeitenMGT610 - Final Term Notes 1-Pages-2Muniba ChNoch keine Bewertungen

- Business Ethics Bill Gates: Rich Man or Great Man (A Comparative Behavior Analysis of Bill Gates, John Rawls, and Adam Smith)Dokument7 SeitenBusiness Ethics Bill Gates: Rich Man or Great Man (A Comparative Behavior Analysis of Bill Gates, John Rawls, and Adam Smith)cdawg068Noch keine Bewertungen

- Rest Neokohlbergian ApproachDokument10 SeitenRest Neokohlbergian ApproachBobby IlievaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Allen Buchanan - The Egalitarianism of Human RightsDokument33 SeitenAllen Buchanan - The Egalitarianism of Human RightscinfangerNoch keine Bewertungen

- Waldron - Security and Liberty. The Image of BalanceDokument21 SeitenWaldron - Security and Liberty. The Image of BalanceJoel CruzNoch keine Bewertungen

- Carens Aliens and Citizens The Case For Open BordersDokument24 SeitenCarens Aliens and Citizens The Case For Open BordersSwastee RanjanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Mag Forum Ka NaDokument1 SeiteMag Forum Ka NaSabrina LouiseNoch keine Bewertungen

- BioethicsDokument6 SeitenBioethicsDiana Laura LeiNoch keine Bewertungen

- Equality of Educational OpportunityDokument21 SeitenEquality of Educational OpportunitySarah Golloso Rojo100% (1)

- Pilapil Psychologization of InjusticeDokument28 SeitenPilapil Psychologization of InjusticeJuan David Piñeres SusNoch keine Bewertungen

- Scanlon - Why Does Inequality MatterDokument192 SeitenScanlon - Why Does Inequality MatterLuigi LucheniNoch keine Bewertungen

- Art, Education, and The Democratic CommitmentDokument189 SeitenArt, Education, and The Democratic CommitmentMarie-Amour KASSANoch keine Bewertungen

- Social Work Scholars Representation of Rawls A Critique - BanerjeeDokument23 SeitenSocial Work Scholars Representation of Rawls A Critique - BanerjeeKarla Salamero MalabananNoch keine Bewertungen

- Bachelor of Arts (BAG) : (For July 2019 and January 2020 Sessions)Dokument10 SeitenBachelor of Arts (BAG) : (For July 2019 and January 2020 Sessions)Sena HmarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Common GoodDokument13 SeitenCommon GoodXyzzielleNoch keine Bewertungen

- DasguptaDokument76 SeitenDasguptaMichel Monkam MboueNoch keine Bewertungen

- Political Theory State of A DsiciplineDokument30 SeitenPolitical Theory State of A DsiciplineJames Muldoon50% (2)

- Global EgalitarianismDokument17 SeitenGlobal EgalitarianismHasan RazaviNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ge8 Module7Dokument6 SeitenGe8 Module7Claire G. MagluyanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Young Responsibility and Global Justice A Social Connection ModelDokument29 SeitenYoung Responsibility and Global Justice A Social Connection ModelAmanda SilvaNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Well Ordered Republic Frank Lovett Ebook Full ChapterDokument51 SeitenThe Well Ordered Republic Frank Lovett Ebook Full Chapterjoi.york180100% (4)

- Libertarianism Vs EgalitarianismDokument2 SeitenLibertarianism Vs EgalitarianismGlory Ann LaliconNoch keine Bewertungen

- From Corruption To Modernity The Evolution of Romania's Entrepreneurship CultureDokument153 SeitenFrom Corruption To Modernity The Evolution of Romania's Entrepreneurship CultureAlex ObrejanNoch keine Bewertungen

- Do Judges Reason Morally - Jeremy WaldronDokument34 SeitenDo Judges Reason Morally - Jeremy WaldronLeonardo BarbosaNoch keine Bewertungen