Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

The Rise of Regionalisation in The East Asian Television Industry

Hochgeladen von

Bogi TóthOriginalbeschreibung:

Originaltitel

Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

The Rise of Regionalisation in The East Asian Television Industry

Hochgeladen von

Bogi TóthCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Edith Cowan University

Copyright Warning

You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose

of your own research or study.

The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or

otherwise make available electronically to any other person any

copyright material contained on this site.

You are reminded of the following:

Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons

who infringe their copyright.

A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a

copyright infringement.

A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to

offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher

penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for

offences and infringements involving the conversion of material

into digital or electronic form.

The rise of regionalisation in the East Asian television

industry: A case study of trendy drama 2000-2012

By

Hsin-Pey Peng

Bachelor of Journalism

Master of Media Studies

This thesis is presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

Faculty of Education and Arts

Edith Cowan University

2012

i

Abstract

This thesis examines the contemporary Taiwanese television industry and its

influence on the Asian TV market and popular culture in Asia. It explores the East

Asian TV industrys ability to produce a specific regional TV genre that of trendy

drama as a means of representing the tastes and lifestyles of a new audience. I claim in

the thesis that the East Asian TV industries have produced trendy drama for an

emerging middle class audience in Asia. Trendy drama still is one of the most popular

genres at the level of local TV productions; it can also be sold to an Asian regional

audience. The main premise of the study is that the media has the symbolic power to

centralise most social resources and technology, and because of that they can produce

certain cultural meanings influential to ordinary peoples social and cultural experience.

A study of the rise of regionalisation which specifically focused on the East

Asian TV industry, has led to this case study of trendy drama. In the case study I

analyse how East Asian TV industries produce and sell these types of local TV

productions to a wider TV market. After the review of regionalisation literature, the

study examines the specific content of the TV genre, trendy drama, within the context of

the Asian TV market. This raises questions about the role of trendy drama and its

function in the rise of regionalisation from political and economic perspectives. The

answers to these questions are then used to examine the production of Taiwanese idol

drama through a filmic and semiotic analysis. The earlier findings are supported by the

television producers and directors (professionals) practical insights into why and how

they produce trendy drama for the Asian market. Macro- and micro-level approaches

used in this study demonstrate the transition from a global television industry dominated

by America to the way East Asian TV industries earlier on drew from the American TV

industrys values, technical knowledge and resources. However, ultimately the East

Asian TV industry developed their own expertise which is why they now have the

symbolic power to sell to audiences within the region. Furthermore, East Asian TV

industries today have the ability to centralise enormous resources so they can produce

culturally shared meanings, which is becoming part of popular culture in Asia.

Consequently, the medias symbolic power enhances the rise of regionalisation in East

Asian TV industries. It is intended that this project will inform further debate about the

changing configuration of television markets within the Asian region and the role of the

media in mediating popular culture within the contemporary media age.

ii

Declaration

I certify that this thesis does not, to the best of my knowledge and belief:

(i) incorporate without acknowledgement any material previously submitted

for a degree or diploma in any institution of higher education;

(ii) contain any material previously published or written by another person

except where due reference is made in the text; or

(iii) contain any defamatory material.

Hisn-Pey Peng 22 June 2012

Name Signature Date of Submission

iii

Acknowledgements

This has been a long journey. In this journey, God guided, inspired and helped me

to fulfill my aim with HIS enormous, endless love. Praise God. In this journey, when I

confronted obstacles and personal issues, God always sent angels.

This thesis has been benefited from the help of many people. I would like to thank

my Principal Supervisor Dr. Debbie Rodan and my Associate Supervisor Dr. George

Karpathakis for their supportive criticism and generous readings of chapter drafts along this

journey. They put a lot of effort into helping me to cope with the complexity of my research.

I appreciate, in particular, Dr. Rodans significant and in-depth scholarship ideas, helping

me to clearly think through the research. I also thank Dr. Karpathakis for being very

generous in contributing a practical and expert approach for my thesis.

I would also like to acknowledge the ongoing support of Dr. Jo McFarlanes

endeavours in terms of my academic writing skill. Dr. McFarlane was very patient in

exploring the best way for me to improve my English expression. I also extend gratitude to

Dr. Lyndall Adams assistance with my research methodology.

My sincere thankfulness to the Ministry of Education of Taiwan for recognising the

significance of my research project and awarding me a Studying Abroad Scholarship

between 2009 and 2010. I am also thankful for ECU granting me a Postgraduate Research

Scholarship in 2010. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Mark W Hackling and

Coordinator Sarah Kearn for their support in dealing with the progress of my studies.

In the duration of my doctoral research, it has been pleasure for me to study in the

room 3.205 with lovely doctoral mates. Many thanks to Sally Stewart, Talhy Stotzer and

John Ryan for being so helpful and encouraging to me with their collegiality and friendship.

My special appreciation goes to Mr. Ilyat Kuzhagaliyevs devotion in this journey.

Thanks to Ilyat for looking after me while he was in Perth. And, my best friend, Miss Ting-

Yun Liang has supported me without any conditions. You are the warmest angels to me.

My final thanks go to my beloved family. Thanks to my father, brother and sisters

for allowing me to be childish to pursue my dream. Finally, I would like to send my

appreciation to heaven to my mother. I know that she is happy to see I have finally reached

my dream.

iv

Table of Contents

Abstract ............................................................................................................................. i

Declaration ....................................................................................................................... ii

Acknowledgements......................................................................................................... iii

Table of Contents ........................................................................................................... iv

List of Figures ................................................................................................................ vii

List of Tables .................................................................................................................. xi

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................. 1

Here and There: Present and Past ........................................................................................ 1

Research Background: What Has Been Happening? ......................................................... 5

Terms Used for the Study ...................................................................................................... 9

Aim of Research.................................................................................................................... 14

Theoretical Perspective ........................................................................................................ 15

Methodology Qualitative Research with Case Study ..................................................... 18

Case study ......................................................................................................................... 21

Integrated literature review .............................................................................................. 21

Textual analysis ................................................................................................................. 23

Semiotic analysis ............................................................................................................... 24

Formal filmic analysis ....................................................................................................... 26

Expert interviews with in-depth interview ......................................................................... 27

The Structure of the Thesis ................................................................................................. 29

Limitations ............................................................................................................................ 34

PART I: DISCOVERING A SENSE OF REGIONALISATION IN ASIA 35

Chapter 2: From American and Japanese Cultural Imperialism to the Rise of

Regionalisation .............................................................................................................. 36

Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 36

American Cultural Imperialism as Globalisation Coverage ............................................ 39

Definition of American cultural imperialism .................................................................... 40

Development of American cultural imperialism ............................................................... 43

Influence of American cultural imperialism in Asia ......................................................... 44

Regionalisation and Japanese Cultural Imperialism ........................................................ 46

Definition of regionalisation ............................................................................................. 48

Japanese imperialism in the Asian region ........................................................................ 50

Cultural discount, cultural proximity and cultural imagination ....................................... 55

South Korean Reaction to Regionalisation ........................................................................ 62

Reaction through government support .............................................................................. 62

National stars and Asian beauty ....................................................................................... 64

Reaction through media power ......................................................................................... 65

Conclusion ............................................................................................................................. 67

v

Chapter 3: Taiwanese TV Industry as Examplar Regi onal i s at i on ................... 70

Introduction ...........................................................................................................................70

The Hollywood Phase (1970s 1990s) .................................................................................73

Political control over local TV productions ......................................................................73

Active importation of American culture.............................................................................79

Resistance to Chinese authority and American cultural imperialism ...............................82

The Japanese Trendy Drama Phase (1990s-2000s) ............................................................84

The impact of satellite and cable television .......................................................................85

Japanese trendy drama in Taiwan .....................................................................................87

Korean trendy drama in Taiwan ........................................................................................88

The Taiwanese Idol Drama Phase (2000-Present) .............................................................90

Reaction through an attempt at adaptation .......................................................................90

Reaction to local TV creativity ..........................................................................................94

Preserve local culture through policy NCC ...................................................................97

Conclusion .............................................................................................................................99

Chapter 4: Trendy Drama as a New Genre in the East Asian Region ................... 102

Introduction .........................................................................................................................102

The Context of Birth: Trendy Drama in Japan ...............................................................103

Japan: A birthplace of trendy drama ...............................................................................104

Elements of trendy drama ................................................................................................107

Legitimising the Genre in the Region................................................................................112

Definition of genre ........................................................................................................113

To be a regional genre ..................................................................................................115

Departure from Traditional Dramas ................................................................................119

New attitudes towards love ..............................................................................................120

A rise in womens self-conviction ....................................................................................123

A rise in individualism .....................................................................................................125

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................130

PART II: ANALYSING TAIWANESE IDOL DRAMAS .......................... 133

Chapter 5: Analysing Black &White () : Highlighting Asian Idols,

Metropolis and Fantasy .............................................................................................. 134

Introduction .........................................................................................................................134

Face as an Icon: New Masculinity in Trendy Drama ......................................................135

New masculinity as Asian idols .......................................................................................136

Close-up shots highlight photogenic characters .............................................................141

De-localisation: Metropolitan Settings ..............................................................................147

Trendy drama and the city: iconic geography signifies metropolis ................................148

Long shots with birds eye view initiate metropolitan imagery .......................................155

Diversity of Storylines: Fantasy Through Myth ..............................................................160

Fantasy elements produced by visual semiotics ..............................................................161

Designed dialogue reinforces the myth ...........................................................................167

Conclusion ...........................................................................................................................169

vi

Chapter 6: Analysing My Queen () (1): Representing the New Image of

Taiwanese women ....................................................................................................... 172

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 172

The New Portrayals of Taiwanese Women...................................................................... 173

Traditional versus modern values in My Queen () .......................................... 174

Taiwanese modern womens conflicting feelings about romantic love ........................... 177

The new image of Taiwanese women registered through male attitudes ........................ 180

New Attitudes Towards Love ............................................................................................ 188

My Queen (): Womens self-conviction in love ............................................... 188

My Queen (): Double-triangular relationship ................................................. 197

My Queen (): New happy ending in trendy drama .......................................... 215

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 221

Chapter 7: Analysing My Queen () (2): Highlighting Social Class through

Costume........................................................................................................................ 223

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 223

My Queen (): Love Tokens Initiate Social Class .............................................. 224

My Queen (): Costumes Represent Social Class .............................................. 227

Wu-Shuangs costume ..................................................................................................... 228

Jia-Jias costume ............................................................................................................. 237

Lucas costume ................................................................................................................ 240

Leslies costume .............................................................................................................. 244

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 250

PART III: LOOKING TO THE FUTURE OF THE GENRE ................... 252

Chapter 8: Producer and Director Perspectives on TV Production in the Region253

Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 253

Motivation for Producing Trendy Drama ........................................................................ 254

From adaptation to creation ........................................................................................... 254

From emphasising idols to looking at content ................................................................ 257

Emphasis on Photogenic Characters and Storylines ....................................................... 259

Symbolism in Idols .......................................................................................................... 260

Attraction of storylines .................................................................................................... 262

Looking to Future Markets ............................................................................................... 263

Conclusion ........................................................................................................................... 265

Chapter 9: Conclusion ................................................................................................ 268

References .................................................................................................................... 272

Appendix 1 ................................................................................................................... 285

Appendix 2 ................................................................................................................... 289

vii

List of Figures

Figure 1.1 The Fierce Wife (). The drama represents extra-marital affairs in

a new

style. ............................................................................................................. 1

Figure 1.2 Japanese manga Boys Over Flowers (Hana yori Dango) vs. Taiwanese idol

drama Meteor Garden () .............................................................. 6

Figure 1.3 Japanese manga vs. Taiwanese idol drama .................................................. 8

Figure 1.4 The research framework ............................................................................. 20

Figure 1.5 A trio of images showing how close-up footage tracking adds drama ..... 26

Figure 2.1 The three phases of evolution of TV development in Taiwan ................... 38

Figure 2.2 A conceptualisation of Galtungs (1971) world system ............................. 51

Figure 2.3 A conceptualization of relations between Japan and the U.S. ................... 52

Figure 3.1 The Taiwanese pop band, F4. .................................................................... 92

Figure 3.2 A Taiwanese idol, Jerry Yan. ..................................................................... 93

Figure 3.3 A Taiwanese idol, Vic Chou. ..................................................................... 93

Figure 3.4 A Japanese idol, Takuya Kimura. .............................................................. 94

Figure 5.1a The two heroes in Black & White () (Yu & Tsai, 2009), Mark

Chao and Vic Chou. ................................................................................. 138

Figure 5.1b The two heroes in Black & White (), Mark Chao and Vic Chou138

Figure 5.2 Vic Chou .................................................................................................. 139

Figure 5.3 Mark Chao ................................................................................................ 140

Figure 5.4 Vic Chou acting as a tramp ...................................................................... 142

Figure 5.5 The footage of Vic Chous close-ups ....................................................... 144

Figure 5.6 The plainclothes policeman walking around KMRT ............................... 149

Figure 5.7 The footage of the policeman walking around KMRT ............................ 149

Figure 5.8 The scene focusing on the Dome of Light ............................................... 150

Figure 5.9 The inserted scenes of the polices preparations for the task ................... 151

Figure 5.10a The Dome of Light .............................................................................. 151

Figure 5.10b The Dome of Light .............................................................................. 152

Figure 5.11 The footage of the two policemen standing under The Dome of Light ... 153

Figure 5.12 The footage focusing on the Dome of Light and the two policemen

standing aside ........................................................................................... 154

viii

Figure 5.13 The scene of the chief watching the monitors .......................................... 154

Figure 5.14 The footage of iconic geography, Tuntex Sky Tower .............................. 156

Figure 5.15 The footage of specific locations in Kaohsiung City ............................... 158

Figure 5.16 The end pictures of the prelude of the theme song .................................. 159

Figure 5.17 Ma speaks to Pi-Zi: are you sure you want sit close to experimental

utensils? .................................................................................................. 163

Figure 5.18 Pi-Zi looks up to Ma................................................................................. 163

Figure 5.19 Ma concentrates on manipulating the experimental utensils. .................. 164

Figure 5.20 The inserted close-up shots of the characters looking at Ma ................... 164

Figure 5.21 The footage of Mas action on the experiment ........................................ 165

Figure 5.22 The footage of Mas narration for his story ............................................. 166

Figure 5.23 The footage of Ma displaying the result of the experiment ..................... 168

Figure 6.1 Wu-Shuangs monologue ......................................................................... 178

Figure 6.2 The footage of Wu-Shuangs monologue ................................................ 178

Figure 6.3 Wu-Shuangs soliloquy ............................................................................ 179

Figure 6.4 Lucass monologue .................................................................................. 181

Figure 6.5 Lucass voice-over ................................................................................... 182

Figure 6.6 Lucas stops Wu-Shuang and brings her a dress ....................................... 184

Figure 6.7 The footage that Lucas brings an evening bag for Wu-Shuang ............... 185

Figure 6.8 The footage of Lucas talking out items one by one from Wu-Shuangs

bag ............................................................................................................ 185

Figure 6.9 The footage of Lucas putting a scarf on Wu-Shuangs neck ................... 186

Figure 6.10 The footage of Wu-Shuangs pretence at smoking .................................. 190

Figure 6.11 Wu-Shuangs dialogue as soliloquy ......................................................... 191

Figure 6.12. Wu-Shuang says: I must win! ............................................................... 192

Figure 6.13 The footage of Wu-Shuang speaking to Lucas. ....................................... 194

Figure 6.14 The footage of Wu-Shuangs and Lucass monologues ........................... 195

Figure 6.15 The footage of Wu-Shuangs monologue ................................................ 196

Figure 6.16 Wu-Shuang is standing near the people and looks unhappy .................... 199

Figure 6.17 Wu-Shuang abruptly walks to pass between Lucas and Jia-Jia ............... 200

Figure 6.18 Wu-Shuang goes straight to the elevator.................................................. 200

Figure 6.19 Wu-Shuang moves her body in between the door.................................... 201

Figure 6.20 The footage of Wu-Shuangs monologue ................................................ 202

Figure 6.21 Wu-Shuangs monologue ......................................................................... 203

Figure 6.22 The long shot of the restaurant ................................................................. 205

ix

Figure 6.23 The shot of Lucass tracking-in close-up ................................................. 206

Figure 6.24 The shot of Wu-Shuangs tracking-in close-up ........................................ 206

Figure 6.25 Jia-Jia looks vague and is out of focus while Lucas is in the deep-focus

shot ........................................................................................................... 207

Figure 6.26 The close-up shot of Lucass looking toward Wu-Shuang includes

Jai-Jai, who is gazing at Lucas ................................................................. 208

Figure 6.27 The rack-focusing shots to signify that Lucas has no romantic intentions

to Jia-Jia .................................................................................................... 208

Figure 6.28 The rack-focusing shots conveying Wu-Shuang and Lucass intimacy

in contrast to Lucas and Jia-Jias friendship ............................................ 209

Figure 6.29 Leslie says: I remember Wu-Shuang doesnt eat snow cake ................ 210

Figure 6.30 Wu-Shuang appears astonished and frozen with shock when hearing

Leslies voice ............................................................................................ 210

Figure 6.31 The shot of Wu-Shuang and Lucas tracks sideways towards Wu-

Shuangs right side ................................................................................... 211

Figure 6.32 Lucas talks to Wu-Shuang: Is he Mr. Polar Bear? Not special! .......... 211

Figure 6.33 The close-up shot of Wu-Shuang inserted with a flashback. ................... 212

Figure 6.34 Deep-focus close-up shot on Wu-Shuang highlights her inner feelings .. 212

Figure 6.35 Leslie is walking to Wu-Shuang slowly. .................................................. 213

Figure 6.36 The deep-focus close-up shot of Wu-Shuang signifies that Leslie is

not part of her emotions ........................................................................... 213

Figure 6.37 Wu-Shuangs over-over ........................................................................... 216

Figure 6.38 The footage of Lucas monologue ........................................................... 218

Figure 6.39 The footage of Lucass soliloquy and Wu-Shuangs monologue ............ 219

Figure 6.40 The extreme long shot with the church in the background. ..................... 220

Figure 7.1 A photograph of a polar bear as a token for Wu-Shuang from Leslie ..... 225

Figure 7.2 The rubber bracelet, the token for Lucas from his past love .................... 225

Figure 7.3 Close-up of the rubber bracelet token for Lucas from his past love ........ 226

Figure 7.4 Fashion conscious Wu-Shuang walking on the street .............................. 229

Figure 7.5 Fashion conscious Wu-Shuang walking on the street .............................. 229

Figure 7.6 Wu-Shuang appears in a white blouse and black skirt ............................. 231

Figure 7.7 Wu-Shuang carries a white leather bag .................................................... 232

Figure 7.8 Wu-Shuang wearing a silver necklace and bracelet ................................. 233

Figure 7.9 Wu-Shuang wears a purple dress of knit-pile fabric ................................ 234

Figure 7.10 Wu-Shuang wears a purple dress of knit-pile fabric ................................ 235

Figure 7.11 Wu-Shuang appears in thinner fabric clothes in the later episodes .......... 236

Figure 7.12 Wu-Shuangs hairstyle in the drama ........................................................ 237

x

Figure 7.13 Jia-Jias first appearance in the drama ..................................................... 238

Figure 7.14 The colours of Lucas costume in the drama ........................................... 241

Figure 7.15 Lucass black helmet with a red pointed line on the top .......................... 242

Figure 7.16 Lucas wears a three piece suit. ................................................................. 243

Figure 7.17 Lucas often wears hoodies in the drama .................................................. 243

Figure 7.18 Leslie jumps into the pool ........................................................................ 245

Figure 7.19 Leslie wears a white shirt and dark blue jeans ......................................... 246

Figure 7.20 Leslies apparel ........................................................................................ 248

Figure 7.21 Leslies apparel ........................................................................................ 248

Figure 7.22 The last appearances of Leslie in the drama ............................................ 249

xi

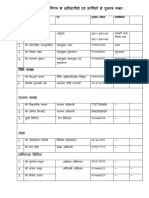

List of Tables

Table 1.1 The primary countries producing trendy drama and their export

countries. .................................................................................................... 13

Table 3. 1a The development of Taiwans TV technology 1930-2012 .72

Table 3.1 Proportion of programming in the Taiwanese language (Tai-yu) .............. 77

Table 3.2 Percentage of imported programs on television between 1969 and

1998 ............................................................................................................ 80

1

Chapter 1

Introduction

One night, the unfaithful husband, Rui-Fan, confessed his betrayal to his

wife with tears and the words: Even if I am dying, I would like to go back

to the life we used to have. At that moment, his wife, An-Zhen, looked at

Rui-Fan, touching his face with tears, and said sympathetically but with

conviction: But, Rui-Fan, I cant go back anymore.

(The Fierce Wife, 2011, Episode 23; translated by the researcher)

Here and There: Present and Past

On Friday 15 April 2011, a Taiwanese TV station broadcast the final episode of

The Fierce Wife () (Wang &Xu, 2011)(see Figure 1.1), a Taiwanese TV

drama about how a young couple confronted their extra-marital affairs. The excerpt

above spoken at the end of the episode created the highest viewing rate in that timeslot

(The Fierce Wife catches public attention, 2011).

Figure 1.1 The Fierce Wife (). The drama represents extra-marital affairs

in a new style.

Source: iSET

2

On that day, the Taiwanese people might normally spend their Friday evening

outside. However, about 4 million Taiwanese, almost a quarter of the total Taiwanese

population, sitting in front of the television watching The Fierce Wife (). In

particular, the heroine, An-Zhens dialogue, I cant go back anymore promoted wide

public discussion about this new image of a Taiwanese married woman. Public

discussion revolved around the dialogue; the audience considering that An-Zhens

decision signified a new attitude of Taiwanese modern women toward their marriage.

As the producer Pei-Hua Wang (cited in Yang, 2011) noted, The story does not end

with a wifes forgiveness and return to the family; instead, it is a new start for her

(translated by the researcher). Wang continued, indicating, What I attempted to register

at the end of the story was a rise of womens self-conviction (translated by the

researcher). Thus, through the particular scene of this episode, a new image of a

Taiwanese married woman was constructed, and traditional values of marriage were

reconsidered. This example reveals the spirit of trendy drama; that is, it represents at

least one new fashionable idea.

Extra-marital affairs are not the preferred theme for trendy drama, because they

are deemed a clich, and are often depicted in traditional TV drama. However, the

depiction of extra-marital affairs in The Fierce Wife () (Wang & Xu, 2011)

does not focus on how the husband meets the other woman, as portrayed in traditional

drama. Instead, the depiction of extra-marital affairs here places greater emphasis on the

process of how a Taiwanese woman changes, grows and discovers her sense of self-

worth after her husband betrays her. This new depiction makes the drama appear

differently, when compared with traditional TV dramas that deal with a similar theme.

The drama reveals a specific modern idea that appears to influence current social

phenomena in Taiwan.

After The Fierce Wife () (Wang & Xu, 2011) was broadcast in Taiwan,

other Asian countries showed interest in this new trendy drama, and imported it to their

countries. For instance, The Fierce Wife () was broadcast in Singapore, where

it was renamed The Shrewd Wife () (2011). In addition, Japan started to

broadcast the drama on the Japanese TV channel, BS Channel, from 9

th

June 2011. In

Japan, the drama was entitled Is Marriage Happiness () (2011), and was

broadcast in Mandarin with Japanese subtitles. Meanwhile, the drama was promoted by

the Japanese TV station as the most topical TV drama in Taiwan in 2011 (Cao, 2011).

3

Subsequently, The Fierce Wife () was aired in Mainland China. Because of its

popularity, TV stations in Beijing sought to purchase the original script of the drama,

and then to reproduce it (High rating of viewing The Fierce Wife, 2011). Clearly, the

drama addressed a wide range of interests within several Asian societies, and the new

image of a married Asian woman was therefore circulated within the Asian region.

A similar example occurred 15 years ago in the Japanese TV industry. A popular

Japanese TV drama, Long Vacation (Rongu Bakeishon) (Kameyama & Nagayama,

1996), was produced as a new genre of TV drama in 1996. In Long Vacation (Rongu

Bakeishon), the heroines fianc flees from their wedding with another girl. Afterwards,

the heroine loses her job and becomes an unemployed model. In experiencing this

difficult situation, the heroine conveys her inner thoughts when she says, When I

encounter an obstacle, I see it as a long vacation as a gift from God, by which I can slow

the pace for my life and feel peace (Long Vacation, Episode 4, 00:03:30; translated by

the researcher). The dialogue registers a modern womans independence and a new

attitude about failed relationships, which has not appeared in Japanese TV drama before

(Tang, 2000).

Similar to The Fierce Wife () (Wang & Xu, 2011), the dialogue in

Long Vacation (Rongu Bakeishon) conveys a new idea, which signifies a rise in

womens self-conviction as a contemporary fashionable idea. The dialogue has even

been attuned to todays expectation of what attitudes modern women should hold

towards their lives. Moreover, it seems that the specific idea represented in Long

Vacation (Rongu Bakeishon) is now adopted in The Fierce Wife (). These two

dramas represent a new style of TV drama which may be categorised as trendy drama.

From the two examples of this genre, it is clear that the genre does not appear only here

(in Taiwan) and now (in 2011); it is also showcased there (in Japan) and in the past (in

1996). This new genre, with the specific ideas it represents, thus transcends territorial

limitations because the genre has been circulated within the Asian region (East Asia in

particular). As a consequence, the new genre has been received, accepted and now

acknowledged by East Asian TV industries and Asian audiences as the most popular in

East Asia.

As trendy drama became popular, it was compared with Taiwanese traditional

drama. Generally speaking, trendy drama can be recognised by its basic plotline, age

group target of the audience and representative style. Its plotline mostly shows

characters with modern, positive and happy attitudes towards life and thus 20-30 year-

4

olds are targeted as the audience. The representative style is distinct from other TV

genres in its high production values that depict new cultural expressions, including

extremely beautiful actors, who are very youthful, very fashionable and have sculptured

looks and wear contemporary, stylish costumes. These aspects are features of trendy

drama, differentiating it from traditional drama.

Traditional drama in this study includes popular prime-time TV serials, such as

historical costume drama, modern serial drama and any other contemporary subgenres.

The term traditional drama is used in this research to distinguish between the fashions in

technical and cultural expression used in traditional and trendy dramas. The distinction

has been developed throughout the thesis. In particular, the different cultural

expressions between traditional and trendy drama have been analysed in Chapter 4 and

the different technical expressions have been examined through filmic analysis of

semiotics in Chapter 5, 6 and 7. The distinctions have been further supported by the

insights of TV experts (interviewees) in Chapter 8. Essentially, the plotline of

traditional drama mostly represents sad characters that have had a hard life or have

struggled with difficult situations; the drama settings are often located in rural situations.

For example, the famous Japanese traditional TV drama Oshin (Okamoto & Sugako,

1984) was very popular in many Asian countries; however, the story of the drama

revolves around the life-long struggle and ultimate success of a peasant woman; it is

therefore not counted as a Japanese trendy drama (Yoshiko, 2002).

A few of the traditional TV dramas focus on romance. However, they cannot be

thought of as trendy drama if their settings are not modern. Therefore, if trendy drama is

deemed to be a modern narrative of romance (Chen, 2008, 177), a traditional TV

drama of romance can be referred as traditional romance. For instance, there was one

subgenre, Qiongyao drama () of Taiwanese traditional dramas, which focused

particularly on romance. The name of this subgenre originated from the famous novel

writer, Qiong Yao. In Taiwan, most of the early TV romances were adapted from her

novels and developed into this particular type of traditional drama. Qiongyao drama was

not deemed trendy drama, because it only focused on love stories and rarely mentioned

contemporary lifestyles. In addition, the drama lacked any depiction of younger

peoples love lives and their attitudes towards life. More specifically, the primary

audiences of Qiongyao drama were housewives, who were deemed to be the rural

obason (old women in the countryside) (Yang, 2008, p. 278); they are not considered

to be part of the group of modern women.

5

Research Background: What Has Been Happening?

Before the popularity of trendy drama in Taiwan, I worked as a journalist for

Taiwans TV stations (1997-2001). During this period, I experienced the rise of cable

TV stations, satellite TV stations, and Taiwanese terrestrial television. By being a

journalist in different TV stations, including a Cable TV system and three Satellite TV

stations, I had ample opportunity to observe the range of popular television programs

produced by and for the TV industry. In particular, at the end of 1999, I was assigned to

execute a special report about the new Japanese culture for a Taiwanese news program

in Japan. I produced a series of special reports, and these were regularly broadcast on

Eastern TV in Taiwan during the next year.

Having the chance to observe closely Japanese popular culture, which was

represented by a wide range of cultural symbols, I was deeply impressed with its

influence in Taiwanese and other Asian societies. The influence of Japanese popular

culture seemed to descend upon these areas. The situation can be observed in

contemporary Taiwanese TV circumstances, which was changing into a new

technological landscape based on the overall deregulation of cable TV. Many new TV

channels therefore appeared, broadcasting numerous Japanese TV programs. During

this time, the context of the new TV landscape was specific because Taiwan had

experienced economic and industrial growth, political movement and a resurgence of

local and multiple cultures.

In 2001, I left journalism for further study. During my postgraduate course, a

rise in local consciousness occurred in my homeland, represented in the media through

public forums. I noticed that the rise in local consciousness was particularly emphasised

and represented in the specific TV genre of drama programs. This type of TV drama

was produced based on Taiwans local context, and used the major native language

Tai-yu; thus, it became a popular subgenre of TV drama, Tai-yu drama. At that time,

the popularity of Tai-yu drama, such as Taiwan A-Cheng (Zhou & Lin, 2001), was

demonstrated in its high ratings. In particular, FTV (Formosa TV station), which was

established based on representing Taiwanese local culture, considered Tai-yu drama as

the main component of drama programs. Therefore, in my M.A. project, I focused on

Tai-yu dramas to analyse the relationship between media and popular culture from a

historical perspective. In my M.A. thesis, I examined how the Formosa TV station

constructed Taiwanese consciousness by producing Tai-yu drama between 1997 and

2002.

6

However, the popularity of Tai-yu drama and local consciousness lasted only a

short time. By the time I had completed my masters degree and returned to my TV

journalist position, I was surprised to find that the Taiwanese TV landscape had

apparently shifted into a multi-channel TV environment. TV programs shown on

channels had become much more diverse, expressing multiple cultures. Several

different foreign TV programs appeared in most timeslots on TV channels. Before this

time, American TV programs had been the main source of foreign programming in

Taiwan. However, at that time, Japanese and Korean trendy dramas were imported

largely to fill the available timeslots, as well as to satisfy Taiwanese audiences. A few

Japanese trendy dramas like Long Vacation (Rongu Bakeishon) (Kameyama &

Nagayama, 1996) and Tokyo Love Story (Toukyou Rabu Sutori) (Saimon & Nagayama,

1991), which were originally received through illegal satellite systems by Taiwanese

audiences in the 1990s, started to be broadcast and rebroadcast on different TV channels

in Taiwan. Meanwhile, the broadcast of Korean trendy drama also suddenly increased.

Japanese and Korean trendy dramas took up most of the prime-time slots (6pm 8pm)

and became a regular genre on cable TV channels.

Figure 1.2 Japanese manga Boys Over Flowers (Hana yori Dango) vs. Taiwanese

idol drama Meteor Garden ()

Source: Animation & Comic Weekly / Hudong.com

Broadcasting foreign TV programs impacted on the popularity of the locally

produced Taiwanese TV dramas including Tai-yu drama. The number of Tai-yu dramas

7

during 1997 2002 was therefore on the decline. A new local production of TV drama

appeared; it indeed had a new approach to producing TV drama. The TV drama was

termed Taiwanese idol drama. The first Taiwanese idol drama is Meteor Garden

1

(

) (Chai & Tsai, 2001), which was adapted from a Japanese manga of 1992, Boys

Over Flowers (Hana yori Dango) (Kamio, 1992) (see Figure 1.2). In addition to local

actors, other elements were represented as being Japanese in style, such as the

characters names, costumes, dialogue, settings and narrative. The appearance of

Meteor Garden () caused two different audience reactions. Some audiences

did not think of it as a Taiwanese local drama (Lin, 2006). Despite this the new drama

was popular with younger audiences. Since then, Taiwanese TV producers have begun

producing TV drama following the conventions of this genre. At first, new Taiwanese

TV dramas were produced drawing on Japanese materials, most of them being produced

based on Japanese manga (see Figure1.3). Because of this, the production of Taiwanese

idol drama was criticised as lacking creativity and of being merely representations of

Japanese lifestyles.

1

Meteor Garden () describes a love story between a playboy (dandy) and a poor girl on campus.

8

Figure 1.3 Japanese manga vs. Taiwanese idol drama

Subsequently, the Taiwanese TV industry began developing idol drama with an

emphasis on local material. The Hospital () (Yu & Tsai, 2006) was produced

based on a Taiwanese novel, its director being Yueh-Hsun Tsai, who produced Meteor

Garden (). Another of Tsais works, Black & White () (Yu & Tsai,

2009), was also produced using local scriptwriting. In addition, a Taiwanese TV station,

Sanlih Entertainment Television (SETTV) began producing idol drama in 2001,

forming a team in order to create original stories. In the following years, Taiwanese idol

drama developed into the most popular genre domestically. The programming is now

not merely capable of competing with foreign TV programs within the domestic TV

market; it is also profitable abroad (Lin, 2009). Taiwanese idol dramas produced by

SETTV have been exported to Asian countries, including Thailand, Vietnam, the

Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore in recent years.

9

I have summarised how TV drama in Taiwan developed between 2002 and 2008

after I returned to Taiwan from the U.K. The new TV landscape in Taiwan and the

emergence of the new genre of trendy dramas provides insights into the ways in which

regionalisation has been shaped in Asia, the rise of Asian regionalisation being most

evident through the popularity of Japanese, Korean and Taiwanese trendy dramas. In

the case of Taiwan, trendy drama, as a specific genre in the region, has become the most

popular imported TV program. The drama replaced American TV programs, even

though they had been very popular in the Taiwanese TV market during the 1980s and

1990s.

According to this new TV landscape, I extended my interest in the development

of TV dramas in Taiwan to a wider area of focus on the contemporary context of the TV

marketplace in Asia. Because of this, the development of Taiwanese TV drama could

not be discussed without regard to both the internal changes within Taiwanese media

(including government regulation and policy) and the external impact of East Asian

media markets in the region.

At the outset of this research, I assumed that Taiwanese idol drama would lack

local creativity and production quality, so that there would be few possibilities for

Taiwanese TV production to compete with Japanese and Korean trendy dramas in the

East Asian region. My concern was that this situation could cause Japanese TV to

dominate in the East Asian region and Taiwan would be in a subordinate position.

However, the increasing development of Taiwanese idol drama during the four years of

my doctoral research has surprised me. During this time Taiwans biggest neighbour,

Mainland China has opened up its TV market gradually. Nowadays, the Taiwan media

has opportunities to expand its TV market in local production of Taiwanese idol dramas

to China. This expansion could create profitable outcomes for the Taiwanese TV

producers. This trend enhances the significance of my research on the power of the new

genre, trendy drama.

Terms Used for the Study

This study involves both TV production and cultural expression based on a few

specific ideas about geographical areas that affect how to think about popular culture,

the Asian region and idol dramas. Therefore, the following terms have particular

meanings that need to be clarified:

popular culture

10

regional

Asia/Asian

idol drama

Popular culture has been discussed widely, researchers focusing on its different

perspectives in media and cultural studies. Basically, popular culture refers to the

popular cultural aspects of a society that are accepted by the majority of that culture.

However, when the people who mostly represent popular culture in their life become

the mainstream of the population, popular culture can be confirmed as a demographic

trend which relates to a particular sector of that population and represents the

preferences and tastes of it. For example, popular culture represented in trendy drama

seems to appeal to a younger demographic. Fiske (1987) proposes his perspectives on

popular cultures definition, avowing that popular culture can be deemed a site of

struggle while accepting the power of the forces of dominance (p. 20). Based on

this viewpoint, popular culture has been formulated to exist among the common people

who are distinguished from the upper classes by being against the dominant cultural

hegemony. In this situation, audiences or consumers appear active in creating and

sharing social meanings, which then become popular culture. Nevertheless, Fiske argues

that the people still cannot escape from the dominant forces which articulate their

hegemonic messages in society, since these forces stem from the upper classes that

control most the resources which mediate the messages.

Compared to Fiske, Storeys (2004) perspective on popular culture is more

related to demographics by which the phenomenon can be illustrated by a quantitative

index (p. 4). Storey proposes that the most common understanding of popular culture

is that is widely favoured or well liked by many people (p. 4). Similarly, Lull (2000)

maintains that popular culture is seen to be products or artifacts in this media-saturated

age, therefore tending to be connected to the common values, beliefs and tastes

represented in peoples daily lives. It can exist in various texts and forms but is

connected to the mainstream of the population. To define the term, Lull observes that:

popular culture means that artifacts and styles of human expression develop

from the creativity of ordinary people, and circulate among people

according to their interests, preferences, and tastes. Popular culture thus

comes from people; it is not just given to them. (p. 165)

11

Lulls (2000) perspective points to the difficulty of delineating the question of whether

media content influences popular culture, or whether popular culture leads to media

content.

Indeed, the perspectives of popular culture proposed by Fiske (1987), Storey

(2004) and Lull (2000) above can be employed to explain popular culture in this study.

Their viewpoints virtually show development of trendy drama in different stages.

Initially, trendy drama was created for the middle class in Japan which was emerging in

society and deemed to be neglected in the TV market (Ota, 2004). Accordingly, the

popular culture represented in trendy drama was related to cultural values of the middle

class, which was distinguished from traditional cultures. This is the kind of dimension

that Fiske proposes. Then the drama became more and more popular and was enjoyed

by most audiences, which ultimately increased in number to become the mainstream

target of the TV market. Therefore the popular culture conveyed in trendy drama

developed into what Storey calls the quantitative dimension (p. 4): it represents the

common values of most people. Nevertheless, at this stage it could also be expressed as

resisting existing culture, such as traditional cultural values. For instance, the Taiwanese

female middle class is now a large group in the society; however, the contemporary

female cultural values expressed in trendy drama sometimes reveal middle class

womens resistance to traditional values. This demonstrates that both Fiskes and

Storeys standpoints are compatible in relation to an understanding about popular

culture.

Eventually, trendy drama developed to the stage that the dramas targeted a

broader demographic and so included the popular culture accepted by most common

people in a larger TV market. From Lulls (2000) perspective, popular culture in these

circumstances would be one of the media products created from ordinary peoples

everyday lives. However, as mentioned above, Lulls perspective points to two aspects

of the question: whether media content influences popular culture, or whether popular

culture leads to media content. Basically, these two aspects of the question are included

in the proposition of this study. However, the former suggests that the media has the

ability to derive ideas from the mainstream population to produce images and stories. In

this sense, the images and stories become created events related to a specific social

phenomenon, lifestyles and social experience, which then form popular culture for

ordinary people. Therefore, popular culture, as used in this study, can be related to

certain cultural meanings that help individuals and groups make sense of their everyday

12

lives. This accords with Lulls view which emphasizes the popular culture means that

cultural themes and styles originate in everyday environments, and are later attended to,

interpreted, and used by ordinary people after being commodified and circulated by

the cultural industries and mass media (p. 169). To sum up, popular culture in this

study serves as a sub-term, which can be appropriated and commodified in TV

productions in order to develop regional markets for East Asian TV industries.

Second, regional in this study aims to define the aspects of TV belonging to

specific areas. In particular, this study locates TV productions and popular culture are

located within regionalisation. Accordingly, regional used adjectively preceding a

noun indicates a representative object for and within the Asian region. In this sense,

there are a few cases in which I describe TV programs produced for the Asian TV

market, such as regional programs, regional TV productions or regional genres.

This description follows the manner in which Tunstall (2008) discusses the

representative media production in a region, such as regional media (p. 10). To sum

up, the adjective regional specifically refers to the sense of regionalisation; it does not

mean remove or countryside.

Furthermore, Asia in this study refers to the area where the specific new TV

production, trendy drama, has been broadcast; however, it does not necessarily include

every Asian country. According to Chua (2004), the region, Asia, can be a generally

geographical conception, which represent shared ethnic and cultural roots. He says that:

the adjective Asian is complicated by a multitude of possible cultural

references, from relatively culturally homogeneous countries in East Asian,

such as Japan and Korea to Korea to multiethnic / multiracial / multicultural

/ multireligious / multilingual postcolonial nations in Southeast and South

Asia. (p. 200)

In this sense, Asia can be used to generally scope the market of the specific media

consumption even though a few countries have developed their own particular type of

media products. For instance, India has its own specific genres of media production

including Hindi television and Bollywood films (Tunstall, 2008). In the conditions, the

popularity of trendy drama, as a specific new TV genre originated from East Asia, does

not influence India.

Essentially, the key geographic concept in this study involves two dimensions:

one is TV production and the other is audience reception. The dimension of TV

production primarily refers to East Asia, the region which shares the flow of popular

culture, and includes the nations of Japan, Korea and Taiwan the main Chinese

13

heritage countries (Chua, 2004). The other dimension of this study, audience reception,

involves TV markets that should not only refer to the Chinese heritage countries of

East Asia, but should also include other countries in Asia, such as Thailand, Vietnam

and the Philippines. In short, trendy drama has been mainly produced by Japan, South

Korea and Taiwan, and has been exported to East Asia, Southeast Asia and Chinese

communities throughout the world (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 The primary countries producing trendy drama and their export countries.

Production countries Export countries

Japan

South Korea

Taiwan

East Asia:

Japan

South Korea

China (Mainland China, Hong Kong, Macao)

Taiwan

Southeast Asia

Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam,

Indonesia, Thailand

Chinese communities in the world

Source: Taiwan Audio Video Interactive Service

More clearly, East Asian TV industries have influenced the Asian TV market

overall. Therefore, the geographic term East Asia is used to indicate the production

sources of TV programs, and Asia is used to indicate the markets and cultural spheres,

such as Asian audience and Asian idol. In general, the words Asia and Asian are

used to describe Asian TV markets, the Asian region, Asian audience, Asian women,

Asian idol, Asian beauty, Asian cultural expression, Asian modernity, Asian-oriented

modern lifestyle and the Asian middle class. Occasionally, both Asia and East Asia are

highlighted in the study as Asia, particularly East Asia.

Finally, idol drama is the term employed instead of trendy drama in some

instances in this thesis. The term refers to the genre that is particularly produced by the

Taiwanese TV industry. However, it is adapted from, and equal in meaning to trendy

drama. Basically, the term Taiwanese idol drama is interchangeable with Taiwanese

14

trendy drama. Thus it indicates the desire of the Taiwanese TV industry to highlight its

own brand through an emphasis on the word idol.

Aim of Research

As a result of my experience as a TV journalist, I was acutely aware of the

association between the two fields: East Asian TV productions; and popular culture in

Asia. I attempted to connect this association to a rise of regionalisation in East Asian

TV industries. This idea grew into a rudimentary hypothesis that East Asian TV

industries had the symbolic power to produce a specific TV genre, and this genre served

as a specific symbolic form to circulate certain cultural meanings that then became part

of popular culture in Asia. Consequently, in this thesis, discussions about television

productions and popular culture are integrated to highlight the rise of regionalisation in

East Asian TV industries. Based on this hypothesis, the main aim of this study is to

explore medias symbolic power which has contributed to the rise of regionalisation in

East Asian TV industries.

In order to achieve this aim, I treat trendy drama as the specific TV genre that

East Asian TV industries have produced to signify certain cultural meanings for Asian

audiences. Moreover, the popularity of this genre has caused local TV products in East

Asia to establish a common cultural product within the region. This idea leads to my

overall argument in this thesis. Initially the Japanese TV industry had the largest

number of resources to develop a new TV genre, trendy drama, for the emerging middle

classes in Asia. Resources were acquired because the Japanese TV industry was in a

privileged political position in the 1990s. At that time, the overall development of

satellite TV in Asia enabled Japanese trendy drama to be received widely within the

Asian area. Subsequently, its popularity demonstrated through television ratings

encouraged other Asian countries, such as South Korea and Taiwan, to develop their

local productions, drawing on and adapting this new genre. In such circumstances,

certain cultural meanings, portraying the middle-class lifestyles in Japanese trendy

drama, were reproduced and circulated to be part of popular culture in Asia. As a

consequence, a rise of regionalisation in the East Asian TV industries has grown in the

Asian TV market and now they have the symbolic power through the production of

programming to mediate social reality in Asia.

My research question is constructed as a major research question with two

sub-questions:

15

1. Since the 1990s through local television production, how has the genre of trendy

drama influenced the rise of regionalisation in the East Asian television

industries?

1.1 How did trendy drama become legitimised as a new TV genre in the Asian

region for Asian audiences?

1.2 How has the Taiwanese TV industry achieved cultural exchanges through

genre production in the Asian TV marketplace since 2000?

In effect, the questions revolve around the significance of trendy drama and its

implications for the integrated TV market and popular culture in Asia, particularly in

Taiwan. The questions are outlined to provide a path that can be followed through the

work. Furthermore, based on the research questions, this study is expected to discover

the East Asian medias symbolic power which is a crucial factor in understanding how

TV productions have the power to circulate and mediate popular culture in Asia. The

expected outcome can add to further discussions about the importance of contemporary

medias function in integrating local TV productions and audiences within a region. The

outcome also provides a case study which serves as an exemplar of how to investigate

future TV landscapes in media studies.

Theoretical Perspective

In this thesis, the main argument is based on the perspective of media power,

which is discussed throughout. I draw on Couldrys notion of symbolic power in the

media to discuss how East Asian TV industries influence popular culture in Asia by

producing a specific type of TV drama. In doing so, they are re-shaping the TV

landscape within the Asian region. This discussion suggests that the Asian community

(East Asia in particular) emerges as an imagined community (Anderson, 1983, p. 44)

and becomes an exclusively Asian cultural sphere, wherein the East Asian TV industries

invite audiences to identify with and belong to. Through this imagined community,

Asian (especially East Asian) people are now connected in a more global sense. In this

course, the new genre of TV programs, trendy drama, serves as the most significant

symbolic form to enable the symbolic power of the East Asian TV industries to be

dispersed throughout the Asian region.

Symbolic power, according to Couldry (2000), refers to the authority of media

institutions to centralise resources and circulate knowledge to mediate social reality for

16

ordinary people. In the modern age, Couldry insists that media authority primarily stems

from advanced technological facilities; and because of these facilities, the media is

capable of transforming messages into an imagined discourse which transcends any

other languages used in the ordinary world (p. 20). Connecting Couldrys perspective

with Bourdieus (1991) sense, symbolic power is the power that naturalises medias

authoritative judgments into taken-for-granted depiction of social reality (Surak, 2011,

p. 176). In addition, Thompson (1995) indicates that symbolic power alludes to a

specific group of individuals capacity to draw on resources to perform actions

which may intervene in the course of events (p. 16). The individuals can be associated

with media experts, who are representatives of media institutions, capable of

transforming cultural messages into symbolic content (p. 16).

Moreover, Chouliaraki (2008) proposes that symbolic power is the capacity of

the media to selectively combine resources of languages and image in order to present

distant events as a cause of emotion, reflection and action (p. 329) for a specific

group of audiences. The specific group of audiences in this study could be considered

more broadly as Asian audiences. From the definitions of symbolic power proposed

above, it is clear that medias symbolic power involves social resources, technical

facilities and TV experts. These factors are combined to generate the symbolic power of

the media, thereby enabling media institutions to establish their own sphere of influence

and on that basis, to mediate social reality.

Based on the discussion above, the sphere of influence that media establishes is

to represent the social world. To reinforce this, Couldry (2000) proposes that there is a

symbolic division between media world and ordinary world (p. 20). Symbolic

division is formed based on the media function of framing, which refers to the medias

role as the ritual frame (p. 16). Accordingly, Couldry postulates that media plays a

privileged role in framing our experiences of the social (p. 14), and acting as sources

of social knowledge (p. 4).The framing media provides help for ordinary people to

define social events and convey preferred cultural meanings, so as to mediate social

reality. In other words, media legitimises certain ideas and circulates them as routine

ways of thinking and believing. As a consequence, ordinary people become dependent

on media institutions for the acquisition of their social knowledge and cultural messages;

thereby the authority of media institutions tends to be naturalised (p. 4).

In terms of symbolic power, the most important element of the concept used in

this study is that the media is capable of concentrating resources, using them to create

17

certain cultural meanings. In doing so, the media need to establish symbolic forms to

exercise symbolic power. In my research, a new TV genre, Japanese trendy drama

produced in the 1990s, is an example of a symbolic form which circulates certain

cultural meanings for the Japanese TV industry. At that time, the Japanese TV industry

has relied on two main resources to develop the genre: the emergence of the middle

class in Asia; and the rise of Asian satellite TV. The middle class was an emerging

group in the 1990s in Asia upon which the TV industry drew for ideas to create a new

TV production, mainly portraying the specific lifestyle of the middle class as modern.

Accordingly, the image of the modern lifestyles depicted in Japanese trendy drama was

reproduced through repetitive depictions and circulation within the Asian region.

Meanwhile, the overall satellite service in Asia enabled the TV production of trendy

drama to circulate throughout the region.

In particular, when the Taiwanese audience did not consider existing TV

programs as good as trendy drama in quality, the genre then became distinctive and

preferred in Taiwan. This led to adaptations in the genre, trendy drama performing

symbolically to circulate certain cultural meanings, with the East Asian TV industries

reproducing the genre acting as agents to reinforce the symbolic power of the Japanese

TV industry. In such a collective activity, certain cultural meanings became part of

popular culture in Asia and the TV genre, namely trendy drama, was legitimised as the

media frame for mediating Asian social reality.

A media frame is a type of social reference through which ordinary people can

recognise the mediated world and other peoples experiences. According to Couldry

(2000), because of the medias function of framing, people tend to believe how media

institutions represent social life (p. 16) and to adopt the patterns of thought, language,

and action (p. 4) conveyed in media as the routine for their everyday life.

Furthermore, the media frame could urge a wider range of social structures to reproduce

the represented social knowledge; this also demonstrates the fact that media is power.

As Couldry maintains:

media power the massive concentration of symbolic power in media

institutions is the complex outcome of practice at every level of social

interaction [it is] reproduced through the details of what social actors

(including audience members) do and say. (p. 4)

When trendy drama was legitimised as the most representative TV genre

providing social knowledge for the Asian middle classes, the materials represented in

the genre were also adopted by social members in Asia. This was evident in their

18

behavioural patterns, which then formed the specific social phenomenon. For instance,

in the past two years, more and more young people from Mainland China seek to study

fashion design in Taiwan, because they think fashion as represented in Taiwanese idol

drama is very trendy and popular, believing that Taiwanese fashion is better known than

Chinese fashion (Wen, 2011). This example indicates trendy drama to be acknowledged

as the dominant genre in terms of leading trends in fashion; and that other countries in

the region have gained this knowledge through the television programming.

The symbolic power of the media may also be demonstrated through the

interaction between the Taiwanese TV industry and government organisations. Recently,

Shali Entertainment Television (SETTV) was commissioned by the Ministry of

National Defense R.O.C. (Taiwan) to produce a military drama, Soldier (Yu, Wang &

Ming, 2011), in the genre of idol drama (Soldier in the production of idol drama,

2011). This was unprecedented because military drama is very distinct traditionally

from other entertainment genres. Apparently, trendy drama as a new genre in Taiwan is

considered to have sufficient symbolic power to influence the social world as a whole.

Most people believe that the depiction of social reality in trendy drama is real

reflection of society because it reproduces the dominant sense of reality in other

fields (Fiske, 1987, p. 21), and as a consequence, through the dominant sense of reality,

trendy drama reinforces the symbolic power of the Taiwanese TV industry.

Methodology Qualitative Research with Case Study

My research primarily cuts across two interactive areas TV production and

popular culture. To analyse the connection between these two areas, I have adopted a

qualitative methodology, including a case study. The case study used in this research

was mainly developed based on an integrated literature review, textual analysis and in-

depth interview. The integrated literature review was formed through previous data,

while the textual analysis was developed based on semiotics and formalist analyses.

This triangular, mixed technique was used to solve the complexity of the macro- and

micro-dimensions in this study. The methods reinforced each other and produced

relatively accurate findings. The details of the relationships among the research methods

are represented diagrammatically in Figure 1.4.

The figure shows the research framework to be based on Couldrys (2000)

media/symbolic power paradigm, which was developed to discuss the two dimensions

TV production and popular culture in a social context. This theoretical perspective also

19

directed the case study used in this research. The integrated literature review was

primarily applied in the former chapters of the thesis. The textural analysis was

conducted using formalist film and semiotic analysis. The interview of practitioners was

used to support the discussions of the whole thesis; therefore, it has broadly informed

each chapter.

Figure 1.1 also depicts the relationships among the different methods which

have reinforced each other. For example, the interview informed the textual analysis

and the findings of textual analysis demonstrated the practical perspectives discussed in

the interview. In addition, the figure displays the layout of the procedural relationship in

the research process. The arrows above the chapter frames indicate the method for each

of the chapters. The broken arrows indicate an interactive and reinforcing relationship

among methods, such as formalist film and semiotic analyses, connect and reinforce

each other. The red arrows refer to contribution of methodological outcomes to the

thesis. For example, the outcome of the qualitative research eventually supported the

theoretical perspective. Each method employed as the main methodology in this study

will be elaborated, as follows.

20

Figure 1.4 The research framework

Source: the author

21