Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Bootstrap Methods and Their Application

Hochgeladen von

free615Copyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Bootstrap Methods and Their Application

Hochgeladen von

free615Copyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Bootstrap Methods and their

Application

Anthony Davison

c _2006

A short course based on the book

Bootstrap Methods and their Application,

by A. C. Davison and D. V. Hinkley

c _Cambridge University Press, 1997

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 1

Summary

Bootstrap: simulation methods for frequentist inference.

Useful when

standard assumptions invalid (n small, data not normal,

. . .);

standard problem has non-standard twist;

complex problem has no (reliable) theory;

or (almost) anywhere else.

Aim to describe

basic ideas;

condence intervals;

tests;

some approaches for regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 2

Motivation

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 3

Motivation

AIDS data

UK AIDS diagnoses 19881992.

Reporting delay up to several years!

Problem: predict state of epidemic at end 1992, with

realistic statement of uncertainty.

Simple model: number of reports in row j and column k

Poisson, mean

jk

= exp(

j

+

k

).

Unreported diagnoses in period j Poisson, mean

k unobs

jk

= exp(

j

)

k unobs

exp(

k

).

Estimate total unreported diagnoses from

period j by replacing

j

and

k

by MLEs.

How reliable are these predictions?

How sensible is the Poisson model?

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 4

Motivation

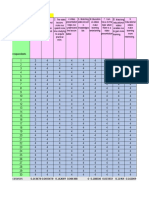

Diagnosis Reporting-delay interval (quarters): Total

period reports

to end

Year Quarter 0

1 2 3 4 5 6 14 of 1992

1988 1 31 80 16 9 3 2 8 6 174

2 26 99 27 9 8 11 3 3 211

3 31 95 35 13 18 4 6 3 224

4 36 77 20 26 11 3 8 2 205

1989 1 32 92 32 10 12 19 12 2 224

2 15 92 14 27 22 21 12 1 219

3 34 104 29 31 18 8 6 253

4 38 101 34 18 9 15 6 233

1990 1 31 124 47 24 11 15 8 281

2 32 132 36 10 9 7 6 245

3 49 107 51 17 15 8 9 260

4 44 153 41 16 11 6 5 285

1991 1 41 137 29 33 7 11 6 271

2 56 124 39 14 12 7 10 263

3 53 175 35 17 13 11 306

4 63 135 24 23 12 258

1992 1 71 161 48 25 310

2 95 178 39 318

3 76 181 273

4 67 133

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 5

Motivation

AIDS data

Data (+), ts of simple model (solid), complex model

(dots)

Variance formulae could be derived painful! but useful?

Eects of overdispersion, complex model, . . .?

++++

+

+

+

+

++

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

++

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

+

Time

D

i

a

g

n

o

s

e

s

1984 1986 1988 1990 1992

0

1

0

0

2

0

0

3

0

0

4

0

0

5

0

0

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 6

Motivation

Goal

Find reliable assessment of uncertainty when

estimator complex

data complex

sample size small

model non-standard

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 7

Basic notions

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 8

Basic notions

Handedness data

Table: Data from a study of handedness; hand is an integer measure

of handedness, and dnan a genetic measure. Data due to Dr Gordon

Claridge, University of Oxford.

dnan hand dnan hand dnan hand dnan hand

1 13 1 11 28 1 21 29 2 31 31 1

2 18 1 12 28 2 22 29 1 32 31 2

3 20 3 13 28 1 23 29 1 33 33 6

4 21 1 14 28 4 24 30 1 34 33 1

5 21 1 15 28 1 25 30 1 35 34 1

6 24 1 16 28 1 26 30 2 36 41 4

7 24 1 17 29 1 27 30 1 37 44 8

8 27 1 18 29 1 28 31 1

9 28 1 19 29 1 29 31 1

10 28 2 20 29 2 30 31 1

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 9

Basic notions

Handedness data

Figure: Scatter plot of handedness data. The numbers show the mul-

tiplicities of the observations.

15 20 25 30 35 40 45

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

dnan

h

a

n

d

1 1

1

2 2 1 5

2

1

5

2

3

1

4

1

1

1 1

1

1

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 10

Basic notions

Handedness data

Is there dependence between dnan and hand for these

n = 37 individuals?

Sample product-moment correlation coecient is

= 0.509.

Standard condence interval (based on bivariate normal

population) gives 95% CI (0.221, 0.715).

Data not bivariate normal!

What is the status of the interval? Can we do better?

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 11

Basic notions

Frequentist inference

Estimator

for unknown parameter .

Statistical model: data y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F, unknown

Handedness data

y = (dnan, hand)

F puts probability mass on subset of R

2

is correlation coecient

Key issue: what is variability of

when samples are

repeatedly taken from F?

Imagine F known could answer question by

analytical (mathematical) calculation

simulation

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 12

Basic notions

Simulation with F known

For r = 1, . . . , R:

generate random sample y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F;

compute

r

using y

1

, . . . , y

n

;

Output after R iterations:

1

,

2

, . . . ,

Use

1

,

2

, . . . ,

R

to estimate sampling distribution of

(histogram, density estimate, . . .)

If R , then get perfect match to theoretical calculation

(if available): Monte Carlo error disappears completely

In practice R is nite, so some error remains

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 13

Basic notions

Handedness data: Fitted bivariate normal model

Figure: Contours of bivariate normal distribution tted to handedness data;

parameter estimates are b

1

= 28.5, b

2

= 1.7, b

1

= 5.4, b

2

= 1.5, b = 0.509.

The data are also shown.

0.000

0.005

0.010

0.015

0.020

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

0

2

4

6

8

10

dnan

h

a

n

d

1 1

1

2 2 1 5

2

1

5

2

3

1

4

1

1

1 1

1

1

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 14

Basic notions

Handedness data: Parametric bootstrap samples

Figure: Left: original data, with jittered vertical values. Centre and

right: two samples generated from the tted bivariate normal distribu-

tion.

0 10 20 30 40 50

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.509

0 10 20 30 40 50

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.753

0 10 20 30 40 50

0

2

4

6

8

1

0

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.533

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 15

Basic notions

Handedness data: Correlation coecient

Figure: Bootstrap distributions with R = 10000. Left: simulation from

tted bivariate normal distribution. Right: simulation from the data by

bootstrap resampling. The lines show the theoretical probability density

function of the correlation coecient under sampling from a tted bivariate

normal distribution.

Correlation coefficient

P

r

o

b

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

d

e

n

s

i

t

y

0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0

.

0

0

.

5

1

.

0

1

.

5

2

.

0

2

.

5

3

.

0

3

.

5

Correlation coefficient

P

r

o

b

a

b

i

l

i

t

y

d

e

n

s

i

t

y

0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0

.

0

0

.

5

1

.

0

1

.

5

2

.

0

2

.

5

3

.

0

3

.

5

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 16

Basic notions

F unknown

Replace unknown F by estimate

F obtained

parametrically e.g. maximum likelihood or robust t of

distribution F(y) = F(y; ) (normal, exponential, bivariate

normal, . . .)

nonparametrically using empirical distribution function

(EDF) of original data y

1

, . . . , y

n

, which puts mass 1/n on

each of the y

j

Algorithm: For r = 1, . . . , R:

generate random sample y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F;

compute

r

using y

1

, . . . , y

n

;

Output after R iterations:

1

,

2

, . . . ,

R

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 17

Basic notions

Nonparametric bootstrap

Bootstrap (re)sample y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F, where

F is EDF of

y

1

, . . . , y

n

Repetitions will occur!

Compute bootstrap

using y

1

, . . . , y

n

.

For handedness data take n = 37 pairs y

= (dnan, hand)

with equal probabilities 1/37 and replacement from original

pairs (dnan, hand)

Repeat this R times, to get

1

, . . . ,

See picture

Results quite dierent from parametric simulation why?

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 18

Basic notions

Handedness data: Bootstrap samples

Figure: Left: original data, with jittered vertical values. Centre and

right: two bootstrap samples, with jittered vertical values.

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.509

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.733

10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

dnan

h

a

n

d

Correlation 0.491

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 19

Basic notions

Using the

Bootstrap replicates

r

used to estimate properties of

.

Write = (F) to emphasize dependence on F

Bias of

as estimator of is

(F) = E(

[ y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F) (F)

estimated by replacing unknown F by known estimate

F:

(

F) = E(

[ y

1

, . . . , y

n

iid

F) (

F)

Replace theoretical expectation E() by empirical average:

(

F) b =

= R

1

R

r=1

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 20

Basic notions

Estimate variance (F) = var(

[ F) by

v =

1

R 1

R

r=1

_

_

2

Estimate quantiles of

by taking empirical quantiles of

1

, . . . ,

For handedness data, 10,000 replicates shown earlier give

b = 0.046, v = 0.043 = 0.205

2

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 21

Basic notions

Handedness data

Figure: Summaries of the

b

. Left: histogram, with vertical line showing

b

.

Right: normal QQ plot of

b

.

Histogram of t

t*

D

e

n

s

i

t

y

0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0

0

.

0

0

.

5

1

.

0

1

.

5

2

.

0

2

.

5

4 2 0 2 4

0

.

5

0

.

0

0

.

5

Quantiles of Standard Normal

t

*

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 22

Basic notions

How many bootstraps?

Must estimate moments and quantiles of

and derived

quantities. Nowadays often feasible to take R 5000

Need R 100 to estimate bias, variance, etc.

Need R 100, prefer R 1000 to estimate quantiles

needed for 95% condence intervals

4 2 0 2 4

2

0

2

4

R=199

Theoretical Quantiles

Z

*

4 2 0 2 4

2

0

2

4

R=999

Theoretical Quantiles

Z

*

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 23

Basic notions

Key points

Estimator is algorithm

applied to original data y

1

, . . . , y

n

gives original

applied to simulated data y

1

, . . . , y

n

gives

can be of (almost) any complexity

for more sophisticated ideas (later) to work,

must often be

smooth function of data

Sample is used to estimate F

F F heroic assumption

Simulation replaces theoretical calculation

removes need for mathematical skill

does not remove need for thought

check code very carefully garbage in, garbage out!

Two sources of error

statistical (

F ,= F) reduce by thought

simulation (R ,= ) reduce by taking R large (enough)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 24

Condence intervals

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 25

Condence intervals

Normal condence intervals

If

approximately normal, then

.

N( +, ), where

has bias = (F) and variance = (F)

If , known, (1 2) condence interval for would be

(D1)

1/2

,

where (z

) = .

Replace , by estimates:

(F)

.

= (

F)

.

= b =

(F)

.

= (

F)

.

= v = (R 1)

1

r

(

)

2

,

giving (1 2) interval

b z

v

1/2

.

Handedness data: R = 10, 000, b = 0.046, v = 0.205

2

,

= 0.025, z

= 1.96, so 95% CI is (0.147, 0.963)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 26

Condence intervals

Normal condence intervals

Normal approximation reliable? Transformation needed?

Here are plots for

=

1

2

log(1 +

)/(1

):

Transformed correlation coefficient

D

e

n

s

i

t

y

0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5

0

.

0

0

.

5

1

.

0

1

.

5

4 2 0 2 4

0

.

5

0

.

0

0

.

5

1

.

0

1

.

5

Quantiles of Standard Normal

T

r

a

n

s

f

o

r

m

e

d

c

o

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

c

o

e

f

f

i

c

i

e

n

t

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 27

Condence intervals

Normal condence intervals

Correlation coecient: try Fishers z transformation:

= (

) =

1

2

log(1 +

)/(1

)

for which compute

b

= R

1

R

r=1

r

, v

=

1

R 1

R

r=1

_

_

2

,

(1 2) condence interval for is

1

_

z

1

v

1/2

_

,

1

_

v

1/2

For handedness data, get (0.074, 0.804)

But how do we choose a transformation in general?

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 28

Condence intervals

Pivots

Hope properties of

1

, . . . ,

R

mimic eect of sampling from

original model.

Amounts to faith in substitution principle: may replace

unknown F with known

F false in general, but often

more nearly true for pivots.

Pivot is combination of data and parameter whose

distribution is independent of underlying model.

Canonical example: Y

1

, . . . , Y

n

iid

N(,

2

). Then

Z =

Y

(S

2

/n)

1/2

t

n1

,

for all ,

2

so independent of the underlying

distribution, provided this is normal

Exact pivot generally unavailable in nonparametric case.

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 29

Condence intervals

Studentized statistic

Idea: generalize Student t statistic to bootstrap setting

Requires variance V for

computed from y

1

, . . . , y

n

Analogue of Student t statistic:

Z =

V

1/2

If the quantiles z

of Z known, then

Pr (z

Z z

1

) = Pr

_

z

V

1/2

z

1

_

= 1 2

(z

no longer denotes a normal quantile!) implies that

Pr

_

V

1/2

z

1

V

1/2

z

_

= 1 2

so (1 2) condence interval is (

V

1/2

z

1

,

V

1/2

z

)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 30

Condence intervals

Bootstrap sample gives (

, V

) and hence

Z

V

1/2

R bootstrap copies of (

, V ):

(

1

, V

1

), (

2

, V

2

), . . . , (

R

, V

R

)

and corresponding

z

1

=

V

1/2

1

, z

2

=

V

1/2

2

, . . . , z

R

=

V

1/2

R

.

Use z

1

, . . . , z

R

to estimate distribution of Z for example,

order statistics z

(1)

< < z

(R)

used to estimate quantiles

Get (1 2) condence interval

V

1/2

z

((1)(R+1))

,

V

1/2

z

((R+1))

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 31

Condence intervals

Why Studentize?

Studentize, so Z

D

N(0, 1) as n . Edgeworth series:

Pr(Z z [ F) = (z) +n

1/2

a(z)(z) +O(n

1

);

a() even quadratic polynomial.

Corresponding expansion for Z

is

Pr(Z

z [

F) = (z) +n

1/2

a(z)(z) +O

p

(n

1

).

Typically a(z) = a(z) +O

p

(n

1/2

), so

Pr(Z

z [

F) Pr(Z z [ F) = O

p

(n

1

).

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 32

Condence intervals

If dont studentize, Z = (

)

D

N(0, ). Then

Pr(Z z [ F) =

_

z

1/2

_

+n

1/2

a

_

z

1/2

_

_

z

1/2

_

+O(n

1

)

and

Pr(Z

z [

F) =

_

z

1/2

_

+n

1/2

a

_

z

1/2

_

_

z

1/2

_

+O

p

(n

1

).

Typically = +O

p

(n

1/2

), giving

Pr(Z

z [

F) Pr(Z z [ F) = O

p

(n

1/2

).

Thus use of Studentized Z reduces error from O

p

(n

1/2

) to

O

p

(n

1

) better than using large-sample asymptotics, for

which error is usually O

p

(n

1/2

).

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 33

Condence intervals

Other condence intervals

Problem for studentized intervals: must obtain V , intervals

not scale-invariant

Simpler approaches:

Basic bootstrap interval: treat

as pivot, get

((R+1)(1))

),

(

((R+1))

).

Percentile interval: use empirical quantiles of

1

, . . . ,

R

:

((R+1))

,

((R+1)(1))

.

Improved percentile intervals (BC

a

, ABC, . . .)

Replace percentile interval with

((R+1)

)

,

((R+1)(1

))

,

where

chosen to improve properties.

Scale-invariant.

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 34

Condence intervals

Handedness data

95% condence intervals for correlation coecient ,

R = 10, 000:

Normal 0.147 0.963

Percentile 0.047 0.758

Basic 0.262 1.043

BC

a

(

= 0.0485,

= 0.0085) 0.053 0.792

Student 0.030 1.206

Basic (transformed) 0.131 0.824

Student (transformed) 0.277 0.868

Transformation is essential here!

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 35

Condence intervals

General comparison

Bootstrap condence intervals usually too short leads to

under-coverage

Normal and basic intervals depend on scale.

Percentile interval often too short but is scale-invariant.

Studentized intervals give best coverage overall, but

depend on scale, can be sensitive to V

length can be very variable

best on transformed scale, where V is approximately

constant

Improved percentile intervals have same error in principle

as studentized intervals, but often shorter so lower

coverage

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 36

Condence intervals

Caution

Edgeworth theory OK for smooth statistics beware

rough statistics: must check output.

Bootstrap of median theoretically OK, but very sensitive to

sample values in practice.

Role for smoothing?

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

....

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

...

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

....

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

...

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

...

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

....

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

..

.

...

..

..

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

...

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Quantiles of Standard Normal

T

*

-

t

f

o

r

m

e

d

i

a

n

s

-2 0 2

-

1

0

-

5

0

5

1

0

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 37

Condence intervals

Key points

Numerous procedures available for automatic construction

of condence intervals

Computer does the work

Need R 1000 in most cases

Generally such intervals are a bit too short

Must examine output to check if assumptions (e.g.

smoothness of statistic) satised

May need variance estimate V see later

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 38

Several samples

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 39

Several samples

Gravity data

Table: Measurements of the acceleration due to gravity, g, given as

deviations from 980,000 10

3

cms

2

, in units of cms

2

10

3

.

Series

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

76 87 105 95 76 78 82 84

82 95 83 90 76 78 79 86

83 98 76 76 78 78 81 85

54 100 75 76 79 86 79 82

35 109 51 87 72 87 77 77

46 109 76 79 68 81 79 76

87 100 93 77 75 73 79 77

68 81 75 71 78 67 78 80

75 62 75 79 83

68 82 82 81

67 83 76 78

73 78

64 78

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 40

Several samples

Gravity data

Figure: Gravity series boxplots, showing a reduction in variance, a shift

in location, and possible outliers.

4

0

6

0

8

0

1

0

0

g

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

series

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 41

Several samples

Gravity data

Eight series of measurements of gravitational acceleration g

made May 1934 July 1935 in Washington DC

Data are deviations from 9.8 m/s

2

in units of 10

3

cm/s

2

Goal: Estimate g and provide condence interval

Weighted combination of series averages and its variance

estimate

8

i=1

y

i

n

i

/s

2

i

8

i=1

n

i

/s

2

i

, V =

_

8

i=1

n

i

/s

2

i

_

1

,

giving

= 78.54, V = 0.59

2

and 95% condence interval of

1.96V

1/2

= (77.5, 79.8)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 42

Several samples

Gravity data: Bootstrap

Apply stratied (re)sampling to series, taking each series as

a separate stratum. Compute

, V

for simulated data

Condence interval based on

Z

V

1/2

,

whose distribution is approximated by simulations

z

1

=

V

1/2

1

, . . . , z

R

=

V

1/2

R

,

giving

(

V

1/2

z

((R+1)(1))

,

V

1/2

z

((R+1))

)

For 95% limits set = 0.025, so with R = 999 use

z

(25)

, z

(975)

, giving interval (77.1, 80.3).

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 43

Several samples

Figure: Summary plots for 999 nonparametric bootstrap simulations.

Top: normal probability plots of t

and z

= (t

t)/v

1/2

. Line on

the top left has intercept t and slope v

1/2

, line on the top right has

intercept zero and unit slope. Bottom: the smallest t

r

also has the

smallest v

, leading to an outlying value of z

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

..

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Quantiles of Standard Normal

t

*

-2 0 2

7

7

7

8

7

9

8

0

8

1

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

..

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

. .

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

. ..

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

..

. ..

.

..

. .

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

..

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

...

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

.

. .

. .

.

.

..

.

.

.

..

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

...

.

.

.

. .

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

..

. . .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

..

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

..

.

.

.

.

..

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

Quantiles of Standard Normal

z

*

-2 0 2

-

1

5

-

1

0

-

5

0

5

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

t*

s

q

r

t

(

v

*

)

77 78 79 80 81

0

.

1

0

.

2

0

.

3

0

.

4

0

.

5

0

.

6

0

.

7

.

.

.

.

.

.

. . .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

. .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

z*

s

q

r

t

(

v

*

)

-15 -10 -5 0 5

0

.

1

0

.

2

0

.

3

0

.

4

0

.

5

0

.

6

0

.

7

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 44

Several samples

Key points

For several independent samples, implement bootstrap by

stratied sampling independently from each

Same basic ideas apply for condence intervals

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 45

Variance estimation

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 46

Variance estimation

Variance estimation

Variance estimate V needed for certain types of condence

interval (esp. studentized bootstrap)

Ways to compute this:

double bootstrap

delta method

nonparametric delta method

jackknife

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 47

Variance estimation

Double bootstrap

Bootstrap sample y

1

, . . . , y

n

and corresponding estimate

Take Q second-level bootstrap samples y

1

, . . . , y

n

from

y

1

, . . . , y

n

, giving corresponding bootstrap estimates

1

, . . . ,

Q

,

Compute variance estimate V as sample variance of

1

, . . . ,

Requires total R(Q + 1) resamples, so could be expensive

Often reasonable to take Q

.

= 50 for variance estimation, so

need O(50 1000) resamples nowadays not infeasible

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 48

Variance estimation

Delta method

Computation of variance formulae for functions of averages

and other estimators

Suppose

= g(

) estimates = g(), and

.

N(,

2

/n)

Then provided g

() ,= 0, have (D2)

E(

) = g() +O(n

1

)

var(

) =

2

g

()

2

/n +O(n

3/2

)

Then var(

)

.

=

2

g

)

2

/n = V

Example (D3):

= Y ,

= log

Variance stabilisation (D4): if var(

)

.

= S()

2

/n, nd

transformation h such that varh(

)

.

=constant

Extends to multivariate estimators, and to

= g(

1

, . . . ,

d

)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 49

Variance estimation

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 50

Variance estimation

Nonparametric delta method

Write parameter = t(F) as functional of distribution F

General approximation:

V

.

= V

L

=

1

n

2

n

j=1

L(Y

j

; F)

2

.

L(y; F) is inuence function value for for observation at y

when distribution is F:

L(y; F) = lim

0

t (1 )F +H

y

t(F)

,

where H

y

puts unit mass at y. Close link to robustness.

Empirical versions of L(y; F) and V

L

are

l

j

= L(y

j

;

F), v

L

= n

2

l

2

j

,

usually obtained by analytic/numerical dierentation.

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 51

Variance estimation

Computation of l

j

Write

in weighted form, dierentiate with respect to

Sample average:

= y =

1

n

y

j

=

w

j

y

j

w

j

1/n

Change weights:

w

j

+ (1 )

1

n

, w

i

(1 )

1

n

, i ,= j

so (D5)

y y

= y

j

+ (1 )y = (y

j

y) +y,

giving l

j

= y

j

y and v

L

=

1

n

2

(y

j

y)

2

=

n1

n

n

1

s

2

Interpretation: l

j

is standardized change in y when increase

mass on y

j

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 52

Variance estimation

Nonparametric delta method: Ratio

Population F(u, x) with y = (u, x) and

= t(F) =

_

xdF(u, x)/

_

udF(u, x),

sample version is

= t(

F) =

_

xd

F(u, x)/

_

ud

F(u, x) = x/u

Then using chain rule of dierentiation (D6),

l

j

= (x

j

u

j

)/u,

giving

v

L

=

1

n

2

_

x

j

u

j

u

_

2

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 53

Variance estimation

Handedness data: Correlation coecient

Correlation coecient may be written as a function of

averages xu = n

1

x

j

u

j

etc.:

=

xu xu

_

(x

2

x

2

)(u

2

u

2

)

_

1/2

,

from which empirical inuence values l

j

can be derived

In this example (and for others involving only averages),

nonparametric delta method is equivalent to delta method

Get

v

L

= 0.029

for comparison with v = 0.043 obtained by bootstrapping.

v

L

typically underestimates var(

) as here!

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 54

Variance estimation

Delta methods: Comments

Can be applied to many complex statistics

Delta method variances often underestimate true variances:

v

L

< var(

Can be applied automatically (numerical dierentation) if

algorithm for

written in weighted form, e.g.

x

w

=

w

j

x

j

, w

j

1/n for x

and vary weights successively for j = 1, . . . , n, setting

w

j

= w

i

+, i ,= j,

w

i

= 1

for = 1/(100n) and using the denition as derivative

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 55

Variance estimation

Jackknife

Approximation to empirical inuence values given by

l

j

l

jack,j

= (n 1)(

j

),

where

j

is value of

computed from sample

y

1

, . . . , y

j1

, y

j+1

, . . . , y

n

Jackknife bias and variance estimates are

b

jack

=

1

n

l

jack,j

, v

jack

=

1

n(n 1)

_

l

2

jack,j

nb

2

jack

_

Requires n + 1 calculations of

Corresponds to numerical dierentiation of

, with

= 1/(n 1)

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 56

Variance estimation

Key points

Several methods available for estimation of variances

Needed for some types of condence interval

Most general method is double bootstrap: can be expensive

Delta methods rely on linear expansion, can be applied

numerically or analytically

Jackknife gives approximation to delta method, can fail for

rough statistics

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 57

Tests

Motivation

Basic notions

Condence intervals

Several samples

Variance estimation

Tests

Regression

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 58

Tests

Ingredients

Ingredients for testing problems:

data y

1

, . . . , y

n

;

model M

0

to be tested;

test statistic t = t(y

1

, . . . , y

n

), with large values giving

evidence against M

0

, and observed value t

obs

P-value, p

obs

= Pr(T t

obs

[ M

0

) measures evidence

against M

0

small p

obs

indicates evidence against M

0

.

Diculties:

p

obs

may depend upon nuisance parameters, those of M

0

;

p

obs

often hard to calculate.

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 59

Tests

Examples

Balsam-r seedlings in 5 5 quadrats Poisson sample?

0 1 2 3 4 3 4 2 2 1

0 2 0 2 4 2 3 3 4 2

1 1 1 1 4 1 5 2 2 3

4 1 2 5 2 0 3 2 1 1

3 1 4 3 1 0 0 2 7 0

Two-way layout: row-column independence?

1 2 2 1 1 0 1

2 0 0 2 3 0 0

0 1 1 1 2 7 3

1 1 2 0 0 0 1

0 1 1 1 1 0 0

Anthony Davison: Bootstrap Methods and their Application, 60

Tests

Estimation of p

obs

Estimate p

obs

by simulation from tted null hypothesis

model

M

0

.

Algorithm: for r = 1, . . . , R:

simulate data set y

1