Beruflich Dokumente

Kultur Dokumente

Land Titles and Deeds

Hochgeladen von

Gladys EsteveCopyright

Verfügbare Formate

Dieses Dokument teilen

Dokument teilen oder einbetten

Stufen Sie dieses Dokument als nützlich ein?

Sind diese Inhalte unangemessen?

Dieses Dokument meldenCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Land Titles and Deeds

Hochgeladen von

Gladys EsteveCopyright:

Verfügbare Formate

Land Titles and Deeds Regalian Doctrine Statute of Limitations

On June 23, 1903, Mateo Cario went to the Court of Land Registration to petition his inscription as

the owner of a 146 hectare land hes been possessing in the then municipality of Baguio. Mateo only

presented possessory information and no other documentation. The State opposed the petition

averring that the land is part of the US military reservation. The CLR ruled in favor of Mateo. The

State appealed. Mateo lost. Mateo averred that a grant should be given to him by reason of

immemorial use and occupation as in the previous case Cansino vs Valdez & Tiglao vs Government.

ISSUE: Whether or not Mateo is the rightful owner of the land by virtue of his possession of it

for some time.

HELD: No. The statute of limitations did not run against the government. The government is still the

absolute owner of the land (regalian doctrine). Further, Mateos possession of the land has not been

of such a character as to require the presumption of a grant. No one has lived upon it for many

years. It was never used for anything but pasturage of animals, except insignificant portions thereof,

and since the insurrection against Spain it has apparently not been used by the petitioner for any

purpose.

While the State has always recognized the right of the occupant to a deed if he proves a possession

for a sufficient length of time, yet it has always insisted that he must make that proof before the

proper administrative officers, and obtain from them his deed, and until he did the State remained

the absolute owner.

Doctrine: The owner of a piece of land has rights not only to its surface but also to everything

underneath and the airspace above it up to a reasonable height. The rights over the land are

indivisible and the land itself cannot be half agricultural and half mineral. The classification must be

categorical; the land must be either completely mineral or completely agricultural.

Facts: These cases arose from the application for registration of a parcel of land filed on February 11,

1965, by Jose de la Rosa on his own behalf and on behalf of his three children, Victoria, Benjamin

and Eduardo. The land, situated in Tuding, Itogon, Benguet Province, was divided into 9 lots and

covered by plan Psu-225009. According to the application, Lots 1-5 were sold to Jose de la Rosa and

Lots 6-9 to his children by Mamaya Balbalio and Jaime Alberto, respectively, in 1964.

The application was separately opposed by Benguet Consolidated, Inc. as to Lots 1-5, Atok Big Wedge

Corporation, as to Portions of Lots 1-5 and all of Lots 6-9, and by the Republic of the Philippines,

through the Bureau of Forestry Development, as to lots 1-9.

In support of the application, both Balbalio and Alberto testified that they had acquired the subject

land by virtue of prescription Balbalio claimed to have received Lots 1-5 from her father shortly after

the Liberation.

Benguet opposed on the ground that the June Bug mineral claim covering Lots 1-5 was sold to it on

September 22, 1934, by the successors-in-interest of James Kelly, who located the claim in

September 1909 and recorded it on October 14, 1909. From the date of its purchase, Benguet had

been in actual, continuous and exclusive possession of the land in concept of owner, as evidenced by

its construction of adits, its affidavits of annual assessment, its geological mappings, geological

samplings and trench side cuts, and its payment of taxes on the land.

For its part, Atok alleged that a portion of Lots 1-5 and all of Lots 6-9 were covered by the Emma and

Fredia mineral claims located by Harrison and Reynolds on December 25, 1930, and recorded on

January 2, 1931, in the office of the mining recorder of Baguio. These claims were purchased from

these locators on November 2, 1931, by Atok, which has since then been in open, continuous and

exclusive possession of the said lots as evidenced by its annual assessment work on the claims, such

as the boring of tunnels, and its payment of annual taxes thereon.

The Bureau of Forestry Development also interposed its objection, arguing that the land sought to be

registered was covered by the Central Cordillera Forest Reserve under Proclamation No. 217 dated

February 16, 1929. Moreover, by reason of its nature, it was not subject to alienation under the

Constitutions of 1935 and 1973.

The trial court denied the application, holding that the applicants had failed to prove their claim of

possession and ownership of the land sought to be registered.

The applicants appealed to the respondent court, which reversed the trial court and recognized the

claims of the applicant, but subject to the rights of Benguet and Atok respecting their mining claims.

In other words, the Court of Appeals affirmed the surface rights of the de la Rosas over the land while

at the same time reserving the sub-surface rights of Benguet and Atok by virtue of their mining

claims. Both Benguet and Atok have appealed to this Court, invoking their superior right of

ownership.

Issue: Whether respondent courts decision, i.e. the surface rights of the de la Rosas over the land

while at the same time reserving the sub-surface rights of Benguet and Atok by virtue of their mining

claim, is correct.

Held: No. Our holding is that Benguet and Atok have exclusive rights to the property in question by

virtue of their respective mining claims which they validly acquired before the Constitution of 1935

prohibited the alienation of all lands of the public domain except agricultural lands, subject to vested

rights existing at the time of its adoption. The land was not and could not have been transferred to

the private respondents by virtue of acquisitive prescription, nor could its use be shared

simultaneously by them and the mining companies for agricultural and mineral purposes. It is true

that the subject property was considered forest land and included in the Central Cordillera Forest

Reserve, but this did not impair the rights already vested in Benguet and Atok at that time. Such

rights were not affected either by the stricture in the Commonwealth Constitution against the

alienation of all lands of the public domain except those agricultural in nature for this was made

subject to existing rights. The perfection of the mining claim converted the property to mineral land

and under the laws then in force removed it from the public domain. By such act, the locators

acquired exclusive rights over the land, against even the government, without need of any further act

such as the purchase of the land or the obtention of a patent over it. As the land had become the

private property of the locators, they had the right to transfer the same, as they did, to Benguet and

Atok. The Court of Appeals justified this by saying there is no conflict of interest between the

owners of the surface rights and the owners of the sub-surface rights. This is rather doctrine, for it is

a well-known principle that the owner of piece of land has rights not only to its surface but also to

everything underneath and the airspace above it up to a reasonable height. Under the aforesaid

ruling, the land is classified as mineral underneath and agricultural on the surface, subject to

separate claims of title. This is also difficult to understand, especially in its practical application.

The Court feels that the rights over the land are indivisible and that the land itself cannot be half

agricultural and half mineral. The classification must be categorical; the land must be either

completely mineral or completely agricultural. In the instant case, as already observed, the land

which was originally classified as forest land ceased to be so and became mineral and completely

mineral once the mining claims were perfected. As long as mining operations were being

undertaken thereon, or underneath, it did not cease to be so and become agricultural, even if only

partly so, because it was enclosed with a fence and was cultivated by those who were unlawfully

occupying the surface.

This is an application of the Regalian doctrine which, as its name implies, is intended for the benefit

of the State, not of private persons. The rule simply reserves to the State all minerals that may be

found in public and even private land devoted to agricultural, industrial, commercial, residential or

(for) any purpose other than mining. Thus, if a person is the owner of agricultural land in which

minerals are discovered, his ownership of such land does not give him the right to extract or utilize

the said minerals without the permission of the State to which such minerals belong.

The flaw in the reasoning of the respondent court is in supposing that the rights over the land could

be used for both mining and non-mining purposes simultaneously. The correct interpretation is that

once minerals are discovered in the land, whatever the use to which it is being devoted at the time,

such use may be discontinued by the State to enable it to extract the minerals therein in the exercise

of its sovereign prerogative. The land is thus converted to mineral land and may not be used by any

private party, including the registered owner thereof, for any other purpose that will impede the

mining operations to be undertaken therein, For the loss sustained by such owner, he is of course

entitled to just compensation under the Mining Laws or in appropriate expropriation proceedings.

ARTICLE XII

NATIONAL ECONOMY AND PATRIMONY

Section 1. The goals of the national economy are a more equitable distribution of opportunities,

income, and wealth; a sustained increase in the amount of goods and services produced by the

nation for the benefit of the people; and an expanding productivity as the key to raising the quality of

life for all, especially the underprivileged.

The State shall promote industrialization and full employment based on sound agricultural

development and agrarian reform, through industries that make full of efficient use of human and

natural resources, and which are competitive in both domestic and foreign markets. However, the

State shall protect Filipino enterprises against unfair foreign competition and trade practices.

In the pursuit of these goals, all sectors of the economy and all region s of the country shall be given

optimum opportunity to develop. Private enterprises, including corporations, cooperatives, and

similar collective organizations, shall be encouraged to broaden the base of their ownership.

Section 2. All lands of the public domain, waters, minerals, coal, petroleum, and other mineral oils,

all forces of potential energy, fisheries, forests or timber, wildlife, flora and fauna, and other natural

resources are owned by the State. With the exception of agricultural lands, all other natural

resources shall not be alienated. The exploration, development, and utilization of natural resources

shall be under the full control and supervision of the State. The State may directly undertake such

activities, or it may enter into co-production, joint venture, or production-sharing agreements with

Filipino citizens, or corporations or associations at least 60 per centum of whose capital is owned by

such citizens. Such agreements may be for a period not exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for

not more than twenty-five years, and under such terms and conditions as may provided by law. In

cases of water rights for irrigation, water supply, fisheries, or industrial uses other than the

development of waterpower, beneficial use may be the measure and limit of the grant.

The State shall protect the nations marine wealth in its archipelagic waters, territorial sea, and

exclusive economic zone, and reserve its use and enjoyment exclusively to Filipino citizens.

The Congress may, by law, allow small-scale utilization of natural resources by Filipino citizens, as

well as cooperative fish farming, with priority to subsistence fishermen and fish workers in rivers,

lakes, bays, and lagoons.

The President may enter into agreements with foreign-owned corporations involving either technical

or financial assistance for large-scale exploration, development, and utilization of minerals,

petroleum, and other mineral oils according to the general terms and conditions provided by law,

based on real contributions to the economic growth and general welfare of the country. In such

agreements, the State shall promote the development and use of local scientific and technical

resources.

The President shall notify the Congress of every contract entered into in accordance with this

provision, within thirty days from its execution.

Section 3. Lands of the public domain are classified into agricultural, forest or timber, mineral lands

and national parks. Agricultural lands of the public domain may be further classified by law according

to the uses to which they may be devoted. Alienable lands of the public domain shall be limited to

agricultural lands. Private corporations or associations may not hold such alienable lands of the

public domain except by lease, for a period not exceeding twenty-five years, renewable for not more

than twenty-five years, and not to exceed one thousand hectares in area. Citizens of the Philippines

may lease not more than five hundred hectares, or acquire not more than twelve hectares thereof,

by purchase, homestead, or grant.

Taking into account the requirements of conservation, ecology, and development, and subject to the

requirements of agrarian reform, the Congress shall determine, by law, the size of lands of the public

domain which may be acquired, developed, held, or leased and the conditions therefor.

Section 4. The Congress shall, as soon as possible, determine, by law, the specific limits of forest

lands and national parks, marking clearly their boundaries on the ground. Thereafter, such forest

lands and national parks shall be conserved and may not be increased nor diminished, except by

law. The Congress shall provide for such period as it may determine, measures to prohibit logging in

endangered forests and watershed areas.

Section 5. The State, subject to the provisions of this Constitution and national development policies

and programs, shall protect the rights of indigenous cultural communities to their ancestral lands to

ensure their economic, social, and cultural well-being.

The Congress may provide for the applicability of customary laws governing property rights or

relations in determining the ownership and extent of ancestral domain.

Section 6. The use of property bears a social function, and all economic agents shall contribute to

the common good. Individuals and private groups, including corporations, cooperatives, and similar

collective organizations, shall have the right to own, establish, and operate economic enterprises,

subject to the duty of the State to promote distributive justice and to intervene when the common

good so demands.

Section 7. Save in cases of hereditary succession, no private lands shall be transferred or conveyed

except to individuals, corporations, or associations qualified to acquire or hold lands of the public

domain.

Section 8. Notwithstanding the provisions of Section 7 of this Article, a natural-born citizen of the

Philippines who has lost his Philippine citizenship may be a transferee of private lands, subject to

limitations provided by law.

Section 9. The Congress may establish an independent economic and planning agency headed by

the President, which shall, after consultations with the appropriate public agencies, various private

sectors, and local government units, recommend to Congress, and implement continuing integrated

and coordinated programs and policies for national development.

Until the Congress provides otherwise, the National Economic and Development Authority shall

function as the independent planning agency of the government.

Section 10. The Congress shall, upon recommendation of the economic and planning agency, when

the national interest dictates, reserve to citizens of the Philippines or to corporations or associations

at least sixty per centum of whose capital is owned by such citizens, or such higher percentage as

Congress may prescribe, certain areas of investments. The Congress shall enact measures that will

encourage the formation and operation of enterprises whose capital is wholly owned by Filipinos.

In the grant of rights, privileges, and concessions covering the national economy and patrimony, the

State shall give preference to qualified Filipinos.

The State shall regulate and exercise authority over foreign investments within its national

jurisdiction and in accordance with its national goals and priorities.

Land Titles and Deeds Aliens disqualified from acquiring public and private lands)

Facts: An alien bought a residential lot and its registration was denied by the Register

of Deeds on the ground that being an alien, he cannot acquire land in this jurisdiction.

When the former brought the case to the CFI, the court rendered judgement sustaining

the refusal of the Register of Deeds.

Issue: WON an alien may own private lands in the Philippines.

Held. No. Public agricultural lands mentioned in Sec. 1, Art. XIII of the 1935

Constitution, include residential, commercial and industrial lands, the Court stated:

Natural resources, with the exception of public agricultural land, shall not be alienated,

and with respect to public agricultural lands, their alienation is limited to Filipino citizens.

But this constitutional purpose conserving agricultural resources in the hands of Filipino

citizens may easily be defeated by the Filipino citizens themselves who may alienate

their agricultural lands in favor of aliens.

Thus Section 5, Article XIII provides:

Save in cases of hereditary succession, no private agricultural lands will be transferred

or assigned except to individuals, corporations or associations qualified to acquire or

hold lands of the public domain in the Philippines.

FACTS:

Acme Plywood & Veneer Co., Inc., a corp. represented by Mr. Rodolfo Nazario, acquired from Mariano

and Acer Infiel, members of the Dumagat tribe 5 parcels of land

possession of the Infiels over the landdates back before the Philippines was discovered by Magellan

land sought to be registered is a private land pursuant to RA 3872 granting absolute ownership to

members of the non-Christian Tribes on land occupied by them or their ancestral lands, whether with the

alienable or disposable public land or within the public domain

Acme Plywood & Veneer Co. Inc., has introduced more than P45M worth of improvements

ownership and possession of the land sought to be registered was duly recognized by the government

when the Municipal Officials of Maconacon, Isabela

donated part of the land as the townsite of Maconacon Isabela

IAC affirmed CFI: in favor of

ISSUES:

1. W/N the land is already a private land - YES

2. W/N the constitutional prohibition against their acquisition by private corporations or associations

applies- NO

HELD: IAC affirmed Acme Plywood & Veneer Co., Inc

1. YES

already acquired, by operation of law not only a right to a grant, but a grant of the Government, for it is

not necessary that a certificate of title should be issued in order that said grant may be sanctioned by the

courts, an application therefore is sufficient

it had already ceased to be of the public domain and had become private property, at least by presumption

The application for confirmation is mere formality, the lack of which does not affect the legal sufficiency

of the title as would be evidenced by the patent and the Torrens title to be issued upon the strength of said

patent.

The effect of the proof, wherever made, was not to confer title, but simply to establish it, as already

conferred by the decree, if not by earlier law

2. NO

If it is accepted-as it must be-that the land was already private land to which the Infiels had a legally

sufficient and transferable title on October 29, 1962 when Acme acquired it from said owners, it must also

be conceded that Acme had a perfect right to make such acquisition

The only limitation then extant was that corporations could not acquire, hold or lease public agricultural

lands inexcess of 1,024 hectares

Das könnte Ihnen auch gefallen

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Von EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Bewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (121)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryVon EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceVon EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (588)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaVon EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItVon EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerVon EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingVon EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (400)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeVon EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (5794)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyVon EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyBewertung: 3.5 von 5 Sternen3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeVon EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (537)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreVon EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersVon EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnVon EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (234)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesVon EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (821)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceVon EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (895)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaVon EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (45)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureVon EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureBewertung: 4.5 von 5 Sternen4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealVon EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealBewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Von EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Bewertung: 4 von 5 Sternen4/5 (98)

- Clerkship HandbookDokument183 SeitenClerkship Handbooksanddman76Noch keine Bewertungen

- Chinese OCW Conversational Chinese WorkbookDokument283 SeitenChinese OCW Conversational Chinese Workbookhnikol3945Noch keine Bewertungen

- George F. Nafziger, Mark W. Walton-Islam at War - A History - Praeger (2008)Dokument288 SeitenGeorge F. Nafziger, Mark W. Walton-Islam at War - A History - Praeger (2008)موسى رجب100% (2)

- Paquete Habana - Case Digest 175 UDokument3 SeitenPaquete Habana - Case Digest 175 UGladys Esteve50% (2)

- C. Rules of Adminissibility - Documentary Evidence - Best Evidence Rule - Loon Vs Power Master Inc, 712 SCRADokument1 SeiteC. Rules of Adminissibility - Documentary Evidence - Best Evidence Rule - Loon Vs Power Master Inc, 712 SCRAJocelyn Yemyem Mantilla VelosoNoch keine Bewertungen

- Commitee Head: Philosophy Department CommitteesDokument1 SeiteCommitee Head: Philosophy Department CommitteesGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- LyricsDokument1 SeiteLyricsGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Minutes PlanningDokument4 SeitenMinutes PlanningGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Philosophy Department Ateneo de Naga University Naga CityDokument1 SeitePhilosophy Department Ateneo de Naga University Naga CityGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- The Case of Nancy Beth Cruzan and Karen Ann QuinlanDokument12 SeitenThe Case of Nancy Beth Cruzan and Karen Ann QuinlanGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Subject-Verb Agreement Basic Rule: ExampleDokument17 SeitenSubject-Verb Agreement Basic Rule: ExampleGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- Program of The Seminar On K-12 ProgramDokument2 SeitenProgram of The Seminar On K-12 ProgramGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- North Sea Continental Shelf CasesDokument2 SeitenNorth Sea Continental Shelf CasesGladys EsteveNoch keine Bewertungen

- SALES - Cui Vs Cui - Daroy Vs AbeciaDokument5 SeitenSALES - Cui Vs Cui - Daroy Vs AbeciaMariaAyraCelinaBatacan50% (2)

- M5a78l-M Lx3 - Placas Madre - AsusDokument3 SeitenM5a78l-M Lx3 - Placas Madre - AsusjuliandupratNoch keine Bewertungen

- Previews 2700-2011 PreDokument7 SeitenPreviews 2700-2011 PrezrolightNoch keine Bewertungen

- 2013 Interview SheetDokument3 Seiten2013 Interview SheetIsabel Luchie GuimaryNoch keine Bewertungen

- 10 Can The Little Horn Change God's LawDokument79 Seiten10 Can The Little Horn Change God's LawJayhia Malaga JarlegaNoch keine Bewertungen

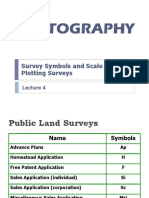

- GE 103 Lecture 4Dokument13 SeitenGE 103 Lecture 4aljonNoch keine Bewertungen

- Owner's Manual & Safety InstructionsDokument4 SeitenOwner's Manual & Safety InstructionsDaniel CastroNoch keine Bewertungen

- Intel Core I37100 Processor 3M Cache 3.90 GHZ Product SpecificationsDokument5 SeitenIntel Core I37100 Processor 3M Cache 3.90 GHZ Product SpecificationshexemapNoch keine Bewertungen

- Parking Tariff For CMRL Metro StationsDokument4 SeitenParking Tariff For CMRL Metro StationsVijay KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Medical Malpractice Claim FormDokument2 SeitenMedical Malpractice Claim Formq747cxmgc8Noch keine Bewertungen

- Gentlemen of The JungleDokument2 SeitenGentlemen of The JungleClydelle Garbino PorrasNoch keine Bewertungen

- India Mineral Report PDFDokument38 SeitenIndia Mineral Report PDFRohan KumarNoch keine Bewertungen

- Airey V Ireland (App. No. 6289 73)Dokument20 SeitenAirey V Ireland (App. No. 6289 73)Christine Cooke100% (1)

- Chapter 2 Quiz - Business LawDokument3 SeitenChapter 2 Quiz - Business LawRayonneNoch keine Bewertungen

- Part IV Civil ProcedureDokument3 SeitenPart IV Civil Procedurexeileen08Noch keine Bewertungen

- MSDS Lead Acetate TapeDokument9 SeitenMSDS Lead Acetate TapesitaNoch keine Bewertungen

- Ambrose Letter 73 To IrenaeusDokument4 SeitenAmbrose Letter 73 To Irenaeuschris_rosebrough_1Noch keine Bewertungen

- MS - 1064 PT 7 2001 TilesDokument16 SeitenMS - 1064 PT 7 2001 TilesLee SienNoch keine Bewertungen

- Thermal Physics Assignment 2013Dokument10 SeitenThermal Physics Assignment 2013asdsadNoch keine Bewertungen

- US v. Esmedia G.R. No. L-5749 PDFDokument3 SeitenUS v. Esmedia G.R. No. L-5749 PDFfgNoch keine Bewertungen

- 96boards Iot Edition: Low Cost Hardware Platform SpecificationDokument15 Seiten96boards Iot Edition: Low Cost Hardware Platform SpecificationSapta AjieNoch keine Bewertungen

- 201908021564725703-Pension RulesDokument12 Seiten201908021564725703-Pension RulesanassaleemNoch keine Bewertungen

- Juz AmmaDokument214 SeitenJuz AmmaIli Liyana Khairunnisa KamardinNoch keine Bewertungen

- D'Alembert's Solution of The Wave Equation. Characteristics: Advanced Engineering Mathematics, 10/e by Edwin KreyszigDokument43 SeitenD'Alembert's Solution of The Wave Equation. Characteristics: Advanced Engineering Mathematics, 10/e by Edwin KreyszigElias Abou FakhrNoch keine Bewertungen

- Tab 82Dokument1 SeiteTab 82Harshal GavaliNoch keine Bewertungen

- People V Oloverio - CrimDokument3 SeitenPeople V Oloverio - CrimNiajhan PalattaoNoch keine Bewertungen